Grand Magazine, August 1923

CHAPTER VI (Continued).

“MR. McTODD!” said the new arrival, on a note of surprise.

“Yes, he found himself able to come, after all.”

“Ah!” said the Efficient Baxter.

It occurred to Psmith as a passing thought, to which he gave no more than a momentary attention, that this spectacled and capable-looking man was gazing at him, as they shook hands, with a curious intensity. But possibly, he reflected, this was merely a species of optical illusion due to the other’s spectacles. Baxter, staring through his spectacles, often gave people the impression of possessing an eye that could pierce six inches of steel and stick out on the other side. Having registered in his consciousness the fact that he had been stared at keenly by this stranger, Psmith thought no more of the matter.

In thus lightly dismissing the Baxterian stare, Psmith had acted injudiciously. He should have examined it more closely and made an effort to analyse it, for it was by no means without its message. It was a stare of suspicion. Vague suspicion as yet, but nevertheless suspicion. Rupert Baxter was one of those men whose chief characteristic is a disposition to suspect their fellows. He did not suspect them of this or that definite crime: he simply suspected them. He had not yet definitely accused Psmith in his mind of any specific tort or malfeasance. He merely had a nebulous feeling that he would bear watching.

Miss Peavey now fluttered again into the centre of things. On the arrival of Baxter she had withdrawn for a moment into the background, but she was not the woman to stay there long. She came forward holding out a small oblong book, which with a languishing firmness she pressed into Psmith’s hands.

“Could I persuade you, Mr. McTodd,” said Miss Peavey, pleadingly, “to write some little thought in my autograph-book and sign it? I have a fountain pen.”

Light flooded the arbour. The Efficient Baxter, who knew where everything was, had found and pressed the switch. He did this not so much to oblige Miss Peavey as to enable him to obtain a clearer view of the visitor. With each minute that passed the Efficient Baxter was finding himself more and more doubtful in his mind about this visitor.

“There!” said Miss Peavey, welcoming the illumination.

Psmith tapped his chin thoughtfully with the fountain pen. He felt that he should have foreseen this emergency earlier. If ever there was a woman who was bound to have an autograph-book, that woman was Miss Peavey.

“Just some little thought . . .”

Psmith hesitated no longer. In a firm hand he wrote the words “Across the pale parabola of Joy . . . ,” added an unfaltering “Ralston McTodd,” and handed the book back.

“How strange,” sighed Miss Peavey.

“May I look?” said Baxter, moving quickly to her side.

“How strange!” repeated Miss Peavey. “To think that you should have chosen that line! There are several of your more mystic passages that I meant to ask you to explain, but particularly ‘Across the pale parabola of Joy . . . !’ ”

“You find it difficult to understand?”

“A little, I confess.”

“Well, well,” said Psmith, indulgently, “perhaps I did put a bit of top-spin on that one.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“I say, perhaps it is a little obscure. We must have a long chat about it—later on.”

“Why not now?” demanded the Efficient Baxter, flashing his spectacles.

“I am rather tired,” said Psmith, with gentle reproach, “after my journey. Fatigued. We writers . . .”

“Of course,” said Miss Peavey, with an indignant glance at the secretary. “Mr. Baxter does not understand the sensitive poetic temperament.”

“A bit earthy, eh?” said Psmith, tolerantly. “A trifle unspiritual? So I thought, so I thought. One of these strong, hard men of affairs, I shouldn’t wonder.”

“Shall we go and find Lord Emsworth, Mr. McTodd?” said Miss Peavey, dismissing the fermenting Baxter with a scornful look. “He wandered off just now. I suppose he is among his flowers. Flowers are very beautiful by night.”

“Indeed, yes,” said Psmith. “And also by day. When I am surrounded by flowers, a sort of divine peace floods over me, and the rough, harsh world seems far away. I feel soothed, tranquil. I sometimes think, Miss Peavey, that flowers must be the souls of little children who have died in their innocence.”

“What a beautiful thought, Mr. McTodd!” exclaimed Miss Peavey, rapturously.

“Yes,” agreed Psmith. “Don’t pinch it! It’s copyright.”

The darkness swallowed them up. Lady Constance turned to the Efficient Baxter, who was brooding with furrowed brow.

“Charming, is he not?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“I said I thought Mr. McTodd was charming.”

“Oh, quite.”

“Completely unspoiled.”

“Oh, decidedly.”

“I am so glad that he was able to come after all. That telegram he sent this afternoon cancelling his visit seemed so curt and final.”

“So I thought it.”

“Almost as if he had taken offence at something and decided to have nothing to do with us.”

“Quite.”

Lady Constance shivered delicately. A cool breeze had sprung up. She drew her wrap more closely about her shapely shoulders, and began to walk to the house. Baxter did not accompany her. The moment she had gone he switched off the light and sat down, chin in hand. That massive brain was working hard.

CHAPTER VII

something fishy

“MISS HALLIDAY,” announced the Efficient Baxter, removing another letter from its envelope and submitting it to a swift, keen scrutiny, “arrives at about three to-day. She is catching the twelve-fifty train.”

He placed the letter on the pile beside his plate; and, having decapitated an egg, peered sharply into its interior as if hoping to surprise guilty secrets. For it was the breakfast-hour, and the members of the house-party, scattered up and down the long table, were fortifying their tissues against another day. An agreeable scent of bacon floated over the scene like a benediction.

Lord Emsworth looked up from the seed-catalogue in which he was immersed. For some time past his enjoyment of the meal had been marred by a vague sense of something missing, and now he knew what it was.

“Coffee!” he said, not violently, but in the voice of a good man oppressed. “I want coffee. Why have I no coffee? Constance, my dear, I should have coffee. Why have I none?”

“I’m sure I gave you some,” said Lady Constance, brightly presiding over the beverages at the other end of the table.

“Then where is it?” demanded his lordship, clinchingly.

Baxter—almost regretfully, it seemed—gave the egg a clean bill of health, and turned in his able way to cope with this domestic problem.

“Your coffee is behind the catalogue you are reading, Lord Emsworth. You propped the catalogue against your cup.”

“Did I? Did I? Why, so I did! Bless my soul!” His lordship, relieved, took an invigorating sip. “What were you saying just then, my dear fellow?”

“I have had a letter from Miss Halliday,” said Baxter. “She writes that she is catching the twelve-fifty train at Paddington, which means that she should arrive at Market Blandings at about three.”

“Who,” asked Miss Peavey, in a low, thrilling voice, ceasing for a moment to peck at her plate of kedgeree, “is Miss Halliday?”

“The exact question I was about to ask myself,” said Lord Emsworth. “Baxter, my dear fellow, who is Miss Halliday?”

Baxter, with a stifled sigh, was about to refresh his employer’s memory when Psmith anticipated him. Psmith had been consuming toast and marmalade with his customary languid grace, and up till now had firmly checked all attempts to engage him in conversation.

“Miss Halliday,” he said, “is a very old and valued friend of mine. We two have, so to speak, pulled the gowans fine. I had been hoping to hear that she had been sighted on the horizon.”

The effect of these words on two of the company was somewhat remarkable. Baxter, hearing them, gave such a violent start that he spilled half the contents of his cup; and Freddie, who had been flitting like a butterfly among the dishes on the sideboard and had just decided to help himself to scrambled eggs, deposited a liberal spoonful on the carpet, where it was found and salvaged a moment later by Lady Constance’s spaniel.

Psmith did not observe these phenomena, for he had returned to his toast and marmalade. He thus missed encountering perhaps the keenest glance that had ever come through Rupert Baxter’s spectacles. It was not a protracted glance, but while it lasted it was like the ray from an oxy-acetylene blowpipe.

“A friend of yours?” said Lord Emsworth. “Indeed? Of course, Baxter, I remember now. Miss Halliday is the young lady who is coming to catalogue the library.”

“What a delightful task!” cooed Miss Peavey. “To live among the stored-up thoughts of dead-and-gone genius!”

“You had better go down and meet her, my dear fellow,” said Lord Emsworth. “At the station, you know,” he continued, clarifying his meaning. “She will be glad to see you.”

“I was about to suggest it myself,” said Psmith.

“Though why the library needs cataloguing,” said his lordship, returning to a problem which still vexed his soul when he had leisure to give a thought to it, “I can’t . . . However . . .”

He finished his coffee and rose from the table. A stray shaft of sunlight had fallen provocatively on his bald head, and sunshine always made him restive.

“Are you going to your flowers, Lord Emsworth?” asked Miss Peavey.

“Eh? What? Yes. Oh, yes. Going to have a look at those lobelias.”

“I will accompany you, if I may,” said Psmith.

“Eh? Why, certainly, certainly.”

“I have always held,” said Psmith, “that there is no finer tonic than a good look at a lobelia immediately after breakfast. Doctors, I believe, recommend it.”

“Oh, I say,” said Freddie, hastily, as he reached the door, “can I have a couple of words with you a bit later on?”

“A thousand if you wish it,” said Psmith. “You will find me somewhere out there in the great open spaces where men are men.”

He included the entire company in a benevolent smile, and left the room.

“How charming he is!” sighed Miss Peavey. “Don’t you think so, Mr. Baxter?”

The Efficient Baxter seemed for a moment to find some difficulty in replying.

“Oh, very,” he said, but not heartily.

“And such a soul! It shines on that wonderful brow of his, doesn’t it!”

“He has a good forehead,” said Lady Constance. “But I wish he wouldn’t wear his hair so short. Somehow it makes him seem unlike a poet.”

Freddie, alarmed, swallowed a mouthful of scrambled egg.

“Oh, he’s a poet all right,” he said, hastily.

“Well, really, Freddie,” said Lady Constance, piqued, “I think we hardly need you to tell us that.”

“No, no, of course. But what I mean is, in spite of his wearing his hair short, you know.”

“I ventured to speak to him of that yesterday,” said Miss Peavey, “and he said he rather expected to be wearing it even shorter very soon.”

“Freddie!” cried Lady Constance, with asperity. “What are you doing?”

A brown lake of tea was filling the portion of the tablecloth immediately opposite the Hon. Frederick Threepwood. Like the Efficient Baxter a few minutes before, sudden emotion had caused him to upset his cup.

THE scrutiny of his lordship’s lobelias had palled upon Psmith at a fairly early stage in the proceedings, and he was sitting on the terrace-wall enjoying a meditative cigarette when Freddie found him.

“Ah, Comrade Threepwood,” said Psmith. “Welcome to Blandings Castle! You said something about wishing to have speech with me, if I remember rightly?”

The Hon. Freddie cast a nervous glance about him, and seated himself on the wall.

“I say,” he said, “I wish you wouldn’t say things like that.”

“Like what, Comrade Threepwood?”

“What you said to the Peavey woman.”

“I recollect having a refreshing chat with Miss Peavey yesterday afternoon,” said Psmith, “but I cannot recall saying anything calculated to bring the blush of shame to the cheek of modesty. What observation of mine was it that meets with your censure?”

“Why, that stuff about expecting to wear your hair shorter. If you’re going to go about saying that sort of thing—well, dash it, you might just as well give the whole bally show away at once and have done with it.”

Psmith nodded gravely.

“Your generous heat, Comrade Threepwood, is not unjustified. It was undoubtedly an error of judgment. If I have a fault—which I am not prepared to admit—it is a perhaps ungentlemanly desire to pull that curious female’s leg. A stronger man than myself might well find it hard to battle against the temptation. However, now that you have called it to my notice, it shall not occur again. In future I will moderate the persiflage. Cheer up, therefore, Comrade Threepwood, and let us see that merry smile of yours, of which I hear such good reports.”

The appeal failed to alleviate Freddie’s gloom. He smote morosely at a fly which had settled on his furrowed brow.

“I’m getting as jumpy as a cat,” he said.

“Fight against this unmanly weakness,” urged Psmith. “As far as I can see, everything is going along nicely.”

“I’m not so sure. I believe that blighter Baxter suspects something.”

“What do you think he suspects?”

“Why, that there’s something fishy about you.”

Psmith winced.

“I would be infinitely obliged to you, Comrade Threepwood, if you would not use that particular adjective. It awakens old memories, all very painful. But let us go more deeply into this matter, for you interest me strangely. Why do you think that cheery old Baxter, a delightful personality if ever I met one, suspects me?”

“It’s the way he looks at you.”

“I know what you mean, but I attribute no importance to it. As far as I have been able to ascertain during my brief visit, he looks at everybody and everything in precisely the same way. Only last night, at dinner, I observed him glaring with keen mistrust at about as blameless and innocent a plate of clear soup as was ever dished up. He then proceeded to get outside it with obvious enjoyment. So possibly you are all wrong about his motive for looking at me like that. It may be admiration.”

“Well, I don’t like it.”

“Nor, from an æsthetic point of view, do I. But we must bear these things manfully. We must remind ourselves that it is Baxter’s misfortune rather than his fault that he looks like a dyspeptic lizard.”

Freddie was not to be consoled. His gloom deepened.

“And it isn’t only Baxter.”

“What else is on your mind?”

“The whole atmosphere of the place is getting rummy, if you know what I mean.” He bent towards Psmith and whispered pallidly. “I say, I believe that new housemaid is a detective!”

Psmith eyed him patiently.

“Which new housemaid, Comrade Threepwood? Brooding, as I do, pretty tensely all the time on deep and wonderful subjects, I have little leisure to keep tab on the domestic staff. Is there a new housemaid?”

“Yes. Susan her name is.”

“Susan? Susan? That sounds all right. Just the name a real housemaid would have.”

“Did you ever,” demanded Freddie, earnestly, “see a real housemaid sweep under a bureau?”

“Does she?”

“Caught her at it in my room this morning.”

“But isn’t it a trifle far-fetched to imagine that she is a detective? Why should she be a detective?”

“Well, I’ve seen such a dashed lot of films where the housemaid or the parlourmaid or what not were detectives. Makes a fellow uneasy.”

“Fortunately,” said Psmith, “there is no necessity to remain in a state of doubt. I can give you an unfailing method by means of which you may discover if she is what she would have us believe her.”

“What’s that?”

“Kiss her.”

“Kiss her!”

“Precisely. Go to her and say: ‘Susan, you’re a very pretty girl . . .’ ”

“But she isn’t.”

“We will assume, for purposes of argument, that she is. Go to her and say: ‘Susan, you are a very pretty girl. What would you do if I were to kiss you?’ If she is a detective, she will reply: ‘How dare you, sir!’—or, possibly, more simply, ‘Sir!’ Whereas if she is the genuine housemaid I believe her to be, and only sweeps under bureaus out of pure zeal, she will giggle and remark: ‘Oh, don’t be silly, sir!’ You appreciate the distinction?”

“How do you know?”

“My grandmother told me, Comrade Threepwood. My advice to you, if the state of doubt you are in is affecting your enjoyment of life, is to put the matter to the test at the earliest convenient opportunity.”

“I’ll think it over,” said Freddie, dubiously.

Silence fell upon him for a space, and Psmith was well content to have it so. He had no specific need of Freddie’s prattle to help him enjoy the pleasant sunshine and the scent of Angus McAllister’s innumerable flowers. Presently, however, his companion was off again. But now there was a different note in his voice. Alarm seemed to have given place to something which appeared to be embarrassment. He coughed several times, and his neatly-shod feet, writhing in self-conscious circles, scraped against the wall.

“I say!”

“You have our ear once more, Comrade Threepwood,” said Psmith, politely.

“I say, what I really came out here to talk about was something else. I say, are you really a pal of Miss Halliday’s?”

“Assuredly. Why?”

“I say!” A rosy blush mantled the Hon. Freddie’s young cheek. “I say, I wish you would put in a word for me, then.”

“Put in a word for you?”

Freddie gulped.

“I love her, dash it!”

“A noble emotion,” said Psmith, courteously. “When did you feel this coming on?”

“I’ve been in love with her for months. But she won’t look at me.”

“That, of course,” agreed Psmith, “must be a disadvantage. I am a child in these matters, but I should imagine that that would stick the gaff into the course of true love to no small extent.”

“I mean, won’t take me seriously and all that. Laughs at me, don’t you know, when I propose. What would you do?”

“I should stop proposing,” said Psmith, having given the matter thought.

“But I can’t.”

“Tut, tut!” said Psmith, severely. “And, in case the expression is new to you, what I mean is ‘Pooh, pooh!’ You mustn’t let what is, after all, a mere habit get a mastery over you. You must struggle, you must use your will-power. Say to yourself: ‘From now on I will not start proposing until after lunch.’ That done, it will be an easy step to do no proposing during the afternoon. And by degrees you will find that you can give it up altogether. The first proposal of the day is the really hard one to drop. Once you have conquered the impulse for the after-breakfast proposal, the rest will be easy.”

“I believe she thinks me a mere butterfly,” said Freddie, who had not been listening to this most valuable homily.

Psmith slid down from the wall and stretched himself.

“Why,” he said, “are butterflies so often described as mere? I have heard them so called a hundred times, and I cannot understand the reason. . . . Well, it would, no doubt, be both interesting and improving to go into the problem, but at this point, Comrade Threepwood, I leave you. I would brood.”

“Yes, but, I say, will you?”

“Will I what?”

“Put in a word for me?”

“If,” said Psmith, “the subject crops up in the course of the chit-chat, I shall be delighted to spread myself with no little vim on the theme of your fine qualities.”

He melted away into the shrubbery, just in time to avoid Miss Peavey, who broke in on Freddie’s meditations a moment later and kept him company till lunch.

THE twelve-fifty train drew up with a grinding of brakes at the platform of Market Blandings, and Psmith, who had been whiling away the time of waiting by squandering money which he could ill afford on the slot-machine which supplied butterscotch, turned and submitted it to a grave scrutiny. Eve Halliday got out of a third-class compartment.

“Welcome to our village, Miss Halliday,” said Psmith, advancing.

Eve regarded him with frank astonishment.

“What are you doing here?” she asked.

“Lord Emsworth was kind enough to suggest that, as we were such old friends, I should come down in the car and meet you.”

“Are we old friends?”

“Surely. Have you forgotten all those happy days in London?”

“There was only one.”

“True. But think how many meetings we crammed into it.”

“Are you staying at the Castle?”

“Yes. And what is more, I am the life and soul of the party. Have you anything in the shape of luggage?”

“I nearly always take luggage when I am going to stay a month or so in the country. It’s at the back somewhere.”

“I will look after it. You will find the car outside. If you care to go and sit in it I will join you in a moment. And, lest the time hangs heavy on your hands, take this. Butterscotch. Delicious, and, so I understand, wholesome. I bought it specially for you.”

A few minutes later, having arranged for the trunk to be taken to the Castle, Psmith emerged from the station and found Eve drinking in the beauties of the town of Market Blandings.

“What a delightful old place,” she said, as they drove off. “I almost wish I lived here.”

“During the brief period of my stay at the Castle,” said Psmith, “the same thought has occurred to me. It is the sort of place where one feels that one could gladly settle down into a peaceful retirement and grow a honey-coloured beard.” He looked at her with solemn admiration. “Women are wonderful,” he said.

“And why, Mr. Bones, are women wonderful?” asked Eve.

“I was thinking at the moment of your appearance. You have just stepped off the train after a two-hour journey, and you are as fresh and blooming as—if I may coin a simile—a rose. How do you do it? When I arrived I was deep in alluvial deposits, and have only just managed to scrape them off.”

“When did you arrive?”

“On the evening of the day on which I met you.”

“But it’s so extraordinary. That you should be here, I mean. I was wondering if I should ever see you again.” Eve coloured a little, and went on rather hurriedly. “I mean, it seems so strange that we should always be meeting like this.”

“Fate, probably,” said Psmith. “I hope it isn’t going to spoil your visit?”

“Oh, no.”

“I could have done with a trifle more emphasis on the last word,” said Psmith, gently. “Forgive me for criticizing your methods of voice-production, but surely you can see how much better it would have sounded, spoken thus: ‘Oh, no!’ ”

Eve laughed.

“Very well, then,” she said. “Oh, no!”

“Much better,” said Psmith. “Much better.”

He began to see that it was going to be difficult to introduce a eulogy of the Hon. Freddie Threepwood into this conversation.

“I’m very glad you’re here,” said Eve, resuming the talk after a slight pause. “Because, as a matter of fact, I’m feeling just the least bit nervous.”

“Nervous?”

“This is my first visit to a place of this size.” The car had turned in at the big stone gates, and they were bowling smoothly up the winding drive. Through an avenue of trees to the right the great bulk of the Castle had just appeared, grey and imposing, against the sky. The afternoon sun glittered on the lake beyond it. “Is everything very stately?”

“Not at all. We are very homely folk, we of Blandings Castle. We go about, simple and unaffected, dropping gracious words all over the place. Lord Emsworth didn’t overawe you, did he?”

“Oh, he’s a dear. And, of course, I know Freddie quite well.”

Psmith nodded. If she knew Freddie quite well, there was naturally no need to talk about him. He did not talk about him, therefore.

“Have you known Lord Emsworth long?” asked Eve.

“I met him for the first time the day I met you.”

“Good gracious!” Eve stared. “And he invited you to the Castle?”

Psmith smoothed his waistcoat.

“Strange, I agree. One can only account for it, can one not, by supposing that I radiate some extraordinary attraction. Have you noticed it?”

“No!”

“No?” said Psmith, surprised. “Ah, well,” he went on, tolerantly, “no doubt it will flash upon you quite unexpectedly sooner or later. Like a thunderbolt or something.”

“I think you’re terribly conceited.”

“Not at all,” said Psmith. “Conceited? No, no. Success has not spoiled me.”

“Have you had any success?”

“None whatever.” The car stopped. “We get down here,” said Psmith, opening the door.

“Here? Why?”

“Because, if we go up to the house, you will infallibly be pounced on and set to work by one Baxter—a delightful fellow, but a whale for toil. I propose to conduct you on a tour round the grounds, and then we will go for a row on the lake. You will enjoy that.”

“You seem to have mapped out my future for me.”

“I have,” said Psmith, with emphasis, and in the monocled eye that met hers Eve detected so beaming a glance of esteem and admiration that she retreated warily into herself and endeavoured to be frigid.

“I’m afraid I haven’t time to wander about the grounds,” she said, aloofly. “I must be going and seeing Mr. Baxter.”

“Baxter,” said Psmith, “is not one of the natural beauties of the place. Time enough to see him when you are compelled to. . . . We are now in the southern pleasaunce or the west home-park or something. Note the refined way the deer are cropping the grass.”

“I haven’t time . . .”

“Leaving the pleasaunce on our left, we proceed to the northern messuage. The dandelions were imported from Egypt by the ninth Earl.”

“Well, anyhow,” said Eve, mutinously, “I won’t come on the lake.”

“You will enjoy the lake,” said Psmith. “The newts are of the famous old Blandings strain. They were introduced, together with the water-beetles, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Lord Emsworth, of course, holds manorial rights over the mosquito-swatting.”

Eve was a girl of high and haughty spirit, and as such strongly resented being appropriated and having her movements directed by one who, in spite of his specious claims, was almost a stranger. But somehow she found her companion’s placid assumption of authority hard to resist. Almost meekly she accompanied him through meadow and shrubbery, over velvet lawns and past gleaming flower-beds, and her indignation evaporated as her eyes absorbed the beauty of it all. She gave a little sigh. If Market Blandings had seemed a place in which one might dwell happily, Blandings Castle was a paradise.

“Before us now,” said Psmith, “lies the celebrated Yew Alley, so called from the yews which hem it in. Speaking in my capacity of guide to the estate, I may say that when we have turned this next corner you will see a most remarkable sight.”

And they did. Before them, as they passed in under the boughs of an aged tree, lay a green vista, faintly dappled with stray shafts of sunshine. In the middle of this vista the Hon. Frederick Threepwood was embracing a young woman in the dress of a housemaid.

PSMITH was the first of the little group to recover from the shock of this unexpected encounter, the Hon. Freddie the last. That unfortunate youth, meeting Eve’s astonished eye as he raised his head, froze where he stood and remained with his mouth open until she had disappeared, which she did a few moments later, led away by Psmith, who, as he went, directed at his young friend a look in which surprise, pain, and reproof were so nicely blended that it would have been hard to say which predominated. All that a spectator could have said with certainty was that Psmith’s finer feelings had suffered a severe blow.

“A painful scene,” he remarked to Eve, as he drew her away in the direction of the house. “But we must always strive to be charitable. He may have been taking a fly out of her eye. Or teaching her jiu-jitsu.”

He looked at her searchingly.

“You seem less revolted,” he said, “than one might have expected. This argues a sweet, shall we say angelic, disposition and confirms my already high opinion of you.”

“Thank you.”

“Not at all. Mark you,” said Psmith, “I don’t think that this sort of thing is a hobby of Comrade Threepwood’s. He probably has many other ways of passing his spare time. Remember that before you pass judgment upon him. Also—Young Blood, and all that sort of thing.”

“I haven’t any intention of passing judgment upon him. It doesn’t interest me what Mr. Threepwood does, either in his spare time or out of it.”

“His interest in you, on the other hand, is vast. I forgot to tell you before, but he loves you. He asked me to mention it if the conversation happened to veer round in that direction.”

“I know he does,” said Eve, ruefully.

“And does the fact stir no chord in you?”

“I think he’s a nuisance.”

“That,” said Psmith, cordially, “is the right spirit. I like to see it. Very well, then, we will discard the topic of Freddie, and I will try to find others that may interest, elevate, and amuse you. We are now approaching the main buildings. I am no expert in architecture, so cannot tell you all I could wish about the facade, but you can see there is a facade, and in my opinion—for what it is worth—a jolly good one. We approach by a sweeping gravel walk.”

“I am going in to report to Mr. Baxter,” said Eve, with decision. “It’s too absurd. I mustn’t spend my time strolling about the grounds. I’m not a guest, I’m an employée. I must see Mr. Baxter at once.”

Psmith inclined his head courteously.

“Nothing easier. That big, open window there is the library. Doubtless Comrade Baxter is somewhere inside, toiling away among the archives.”

“Yes, but I can’t announce myself by shouting to him.”

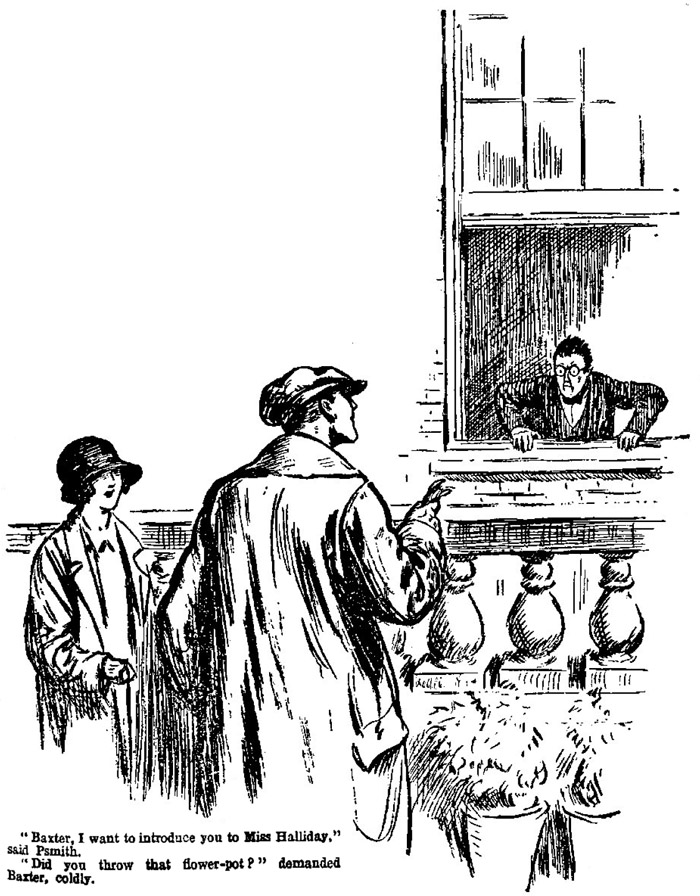

“Assuredly not,” said Psmith. “No need for that at all. Leave it to me.” He stooped and picked up a large flower-pot which stood under the terrace-wall, and before Eve could intervene had tossed it lightly through the open window. A muffled thud, followed by a sharp exclamation from within, caused a faint smile of gratification to illumine his solemn countenance. “He is in. I thought he would be. Ah, Baxter,” he said, graciously, as the upper half of a body surmounted by a spectacled face framed itself suddenly in the window, “a pleasant, sunny afternoon. How is everything?”

The Efficient Baxter struggled for utterance.

“You look like the Blessed Damozel gazing down from the gold bar of Heaven,” said Psmith, genially. “Baxter, I want to introduce you to Miss Halliday. She arrived safely after a somewhat fatiguing journey. You will like Miss Halliday. If I had a library, I could not wish for a more courteous, obliging, and capable cataloguist.”

This striking and unsolicited testimonial made no appeal to the Efficient Baxter. His mind seemed occupied with other matters.

“Did you throw that flower-pot?” he demanded, coldly.

“You will no doubt,” said Psmith. “wish on some later occasion to have a nice long chat with Miss Halliday in order to give her an outline of her duties. I have been showing her the grounds and am about to take her for a row on the lake. But after that she will—and I know I may speak for Miss Halliday in this matter—be entirely at your disposal.”

“Did you throw that flower-pot?”

“I look forward confidently to the pleasantest of associations between you and Miss Halliday. You will find her,” said Psmith, warmly, “a willing assistant, a tireless worker.”

“Did you . . . ?”

“But now,” said Psmith, “I must be tearing myself away. In order to impress Miss Halliday I put on my best suit when I went to meet her. For a row upon the lake something simpler in pale flannel is indicated. I shall only be a few minutes,” he said to Eve. “Would you mind meeting me at the boat-house?”

“I am not coming on the lake with you.”

“At the boat-house in—say—six and a quarter minutes,” said Psmith, with a gentle smile, and pranced into the house like a long-legged mustang.

Eve remained where she stood, struggling between laughter and embarrassment. The Efficient Baxter was still leaning wrathfully out of the library window, and it began to seem a little difficult to carry on an ordinary conversation. The problem of what she was to say in order to continue the scene in an agreeable manner was solved by the arrival of Lord Emsworth, who pottered out from the bushes with a spud in his hand. He stood eyeing Eve for a moment, then memory seemed to wake. Eve’s appearance was easier to remember, possibly, than some of the things which his lordship was wont to forget. He came forward beamingly.

“Ah, there you are, Miss . . . Dear me, I’m really afraid I have forgotten your name. My memory is excellent as a rule, but I cannot remember names . . . Miss Halliday! Of course, of course. Baxter, my dear fellow,” he proceeded, sighting the watcher at the window, “this is Miss Halliday.”

“Mr. McTodd,” said the Efficient One, sourly, “has already introduced me to Miss Halliday.”

“Has he? Deuced civil of him, deuced civil of him. But where is he?” inquired his lordship, scanning the surrounding scenery with a vague eye.

“He went into the house. After,” said Baxter, in a cold voice, “throwing a flower-pot at me.”

“Doing what?”

“He threw a flower-pot at me,” said Baxter, and vanished moodily.

Lord Emsworth stared at the open window, then turned to Eve for enlightenment.

“Why did Baxter throw a flower-pot at McTodd?” he said. “And,” he went on, ventilating an even deeper question, “where the deuce did he get a flower-pot? There are no flower-pots in the library.”

Eve, on her side, was also seeking information.

“Did you say his name was McTodd, Lord Emsworth?”

“No, no. Baxter. That was Baxter, my secretary.”

“No. I mean the one who met me at the station.”

“Baxter did not meet you at the station. The man who met you at the station,” said Lord Emsworth, speaking slowly, for women are so apt to get things muddled, “was McTodd. He’s staying here. Constance asked him, and I’m bound to say when I first heard of it I was not any too well pleased. I don’t like poets as a rule. But this fellow’s so different from the other poets I’ve met. Different altogether. And,” said Lord Emsworth, with not a little heat, “I strongly object to Baxter throwing flower-pots at him. I won’t have Baxter throwing flower-pots at my guests,” he said, firmly, for Lord Emsworth, though occasionally a little vague, was keenly alive to the ancient traditions of his family regarding hospitality.

“Is Mr. McTodd a poet?” said Eve, her heart beating.

“Eh? Oh, yes, yes. There seems to be no doubt about that. A Canadian poet. Apparently they have poets out there. And,” demanded his lordship, ever a fair-minded man, “why not? A remarkably growing country. I was there in the year ’98. Or was it,” he added, thoughtfully passing a muddy hand over his chin and leaving a rich brown stain, “ ’99? I forget. My memory isn’t good for dates . . . If you will excuse me, Miss . . . Miss Halliday, of course . . . if you will excuse me, I must be leaving you. I have to see McAllister, my head-gardener. An obstinate man. A Scotchman. If you go into the house, my sister Constance will give you a cup of tea. I don’t know what the time is, but I suppose there will be tea soon. Never take it myself.”

“Mr. McTodd asked me to go for a row on the lake.”

“On the lake, eh? On the lake?” said his lordship, as if this was the last place in the neighbourhood where he would have expected to hear of people proposing to row. Then he brightened. “Of course, yes, on the lake. I think you will like the lake. I take a dip there myself every morning before breakfast. I find it good for the health and appetite. I plunge in and swim perhaps fifty yards and then return.”

Lord Emsworth suspended the gossip from the training-camp in order to look at his watch. “Dear me,” he said, “I must be going. McAllister has been waiting fully ten minutes. Good-bye, then, for the present, Miss . . . er . . . good-bye.”

And Lord Emsworth ambled off, on his face that look of tense concentration which it always wore when interviews with Angus McAllister were in prospect—the look which stern warriors wear when about to meet a foeman worthy of their steel.

THERE was a cold expression in Eve’s eyes as she made her way slowly to the boat-house. The information which she had just received had come as a shock, and she was trying to adjust her mind to it. When Miss Clarkson had told her of the unhappy conclusion to her old school friend’s marriage to Ralston McTodd, she had immediately, without knowing anything of the facts, arrayed herself loyally on Cynthia’s side and condemned the unknown McTodd uncompromisingly and without hesitation. It was many years since she had seen Cynthia, and their friendship might almost have been said to have lapsed; but Eve’s affection, when she had once given it, was a durable thing, capable of surviving long separation.

She had loved Cynthia at school, and she could feel nothing but animosity towards anyone who had treated her badly. She eyed the glittering water of the lake from under lowered brows, and prepared to be frigid and hostile when the villain of the piece should arrive. It was only when she heard footsteps behind her and turned to perceive Psmith hurrying up, radiant in gleaming flannel, that it occurred to her for the first time that there might have been faults on both sides. She had not known Psmith long, it was true, but already his personality had made a somewhat deep impression on her, and she was loth to believe that he could be the callous scoundrel of her imagination. She decided to suspend judgment until they should be out in mid-water and in a position to discuss the matter without interruption.

“I am a little late,” said Psmith, as he came up. “I was detained by our young friend Freddie. He came into my room and started talking about himself at the very moment when I was tying my tie and needed every ounce of concentration for that delicate task. The recent painful episode appeared to be weighing on his mind to some extent.”

He helped Eve into the boat and started to row. “I consoled him as best I could by telling him that it would probably have made you think all the more highly of him. I ventured the suggestion that girls worship the strong, rough, dashing type of man. And, after I had done my best to convince him that he was a strong, rough, dashing man, I came away. By now, of course, he may have had a relapse into despair; so if you happen to see a body bobbing about in the water as we row along it will probably be Freddie’s.”

“Never mind about Freddie.”

“I don’t, if you don’t,” said Psmith, agreeably. “Very well, then, if we see a body we will ignore it.” He rowed on a few strokes. “Correct me if I am wrong,” he said, resting on his oars and leaning forward, “but you appear to be brooding about something. If you will give me a clue, I will endeavour to assist you to grapple with any little problem which is troubling you. What is the matter?”

Eve, questioned thus directly, found it difficult to open the subject. She hesitated a moment and let the water ripple through her fingers.

“I have only just found out your name, Mr. McTodd,” she said, at length.

Psmith nodded.

“It is always thus,” he said. “Passing through this life, we meet a fellow-mortal, chat awhile, and part; and the last thing we think of doing is to ask him in a manly and direct way what his label is. There is something oddly furtive and shamefaced in one’s attitude towards people’s names. It is as if we shrank from probing some hideous secret. We say to ourselves, ‘This pleasant stranger may be a Snooks or a Buggins. Better not inquire.’ But in my case . . .”

“It was a great shock to me.”

“Now, there,” said Psmith, “I cannot follow you. I wouldn’t call McTodd a bad name, as names go. Don’t you think there is a sort of Highland strength about it? It sounds to me like something out of ‘The Lady of the Lake’ or ‘The Lay of the Last Minstrel.’ ‘The stag at eve had drunk its fill adoon the glen beyint the hill, and welcomed with a friendly nod old Scotland’s pride, young Laird McTodd.’ You don’t think it has a sort of wild romantic ring?”

“I ought to tell you, Mr. McTodd,” said Eve, “that I was at school with Cynthia.”

Psmith was not a young man who often found himself at a loss, but this remark gave him a bewildered feeling such as comes in dreams. It was plain to him that this delightful girl thought she had said something serious, even impressive; but for the moment it did not seem to him to make sense. He sparred warily for time.

“Indeed? With Cynthia? That must have been jolly.”

The harmless observation appeared to have the worst effect upon his companion. The frown came back to her face.

“Oh, don’t speak in that flippant, sneering way,” she said. “It’s so cheap.”

Psmith, having nothing to say, remained silent, and the boat drifted on. Eve’s face was delicately pink, for she was feeling extraordinarily embarrassed. There was something in the solemn gaze of the man before her which made it difficult for her to go on. But, with the stout-heartedness which was one of her characteristics, she stuck to her task.

“After all,” she said, “however you may feel about her now, you must have been fond of poor Cynthia at one time, or I don’t see why you should have married her.”

Psmith, for want of conversation, had begun rowing again. The start he gave at these remarkable words caused him to skim the surface of the water with the left oar in such a manner as to send a liberal pint into Eve’s lap. He started forward with apologies.

“Oh, never mind about that,” said Eve, impatiently. “It doesn’t matter . . . Mr. McTodd,” she said, and there was a note of gentleness in her voice, “I do wish you would tell me what the trouble was.”

Psmith stared at the floor of the boat in silence. He was wrestling with a feeling of injury. True, he had not during their brief conversation at the Senior Conservative Club specifically inquired of Mr. McTodd whether he was a bachelor, but somehow he felt that the man should have dropped some hint as to his married state. True, again, Mr. McTodd had not asked him to impersonate him at Blandings Castle. And yet, undeniably, he felt that he had a grievance.

Psmith’s was an orderly mind. He had proposed to continue the pleasant relations which had begun between Eve and himself, seeing to it that every day they became a little pleasanter, until eventually, in due season, they should reach the point where it would become possible to lay heart and hand at her feet. For there was no doubt in his mind that, in a world congested to overflowing with girls, Eve Halliday stood entirely alone. And now this infernal Cynthia had risen from nowhere to stand between them. Even a young man as liberally endowed with calm assurance as he was might find it awkward to conduct his wooing with such a handicap as a wife in the background.

Eve misinterpreted his silence.

“I suppose you are thinking that it is no business of mine?”

Psmith came out of his thoughts with a start.

“No, no. Not at all.”

“You see, I’m devoted to Cynthia—and I like you.”

She smiled for the first time. Her embarrassment was passing.

“That is the whole point,” she said. “I do like you. And I’m quite sure that if you were really the sort of man I thought you when I first heard about all this, I shouldn’t. The friend who told me about you and Cynthia made it seem as if the whole fault had been yours. I got the impression that you had been very unkind to Cynthia. I thought you must be a brute. And when Lord Emsworth told me who you were, my first impulse was to hate you. I think if you had come along just then I should have been rather horrid to you. But you were late, and that gave me time to think it over. And then I remembered how nice you had been to me and I felt somehow that—that you must really be quite nice, and it occurred to me that there might be some explanation. And I thought that—perhaps—if you would let me interfere in your private affairs—and if things hadn’t gone too far . . . I might do something to help . . . try to bring you together, you know.”

She broke off, a little confused, for now that the words were out she was conscious of a return of her former shyness. Even though she was an old friend of Cynthia’s, there did seem something insufferably officious in this meddling. And when she saw the look of pain on her companion’s face she regretted that she had spoken. Naturally, she thought, he was offended.

In supposing that Psmith was offended, she was mistaken. Internally, he was glowing with a renewed admiration for all those beautiful qualities in her which he had detected, before they had ever met, at several yards’ range across the street from the window of the Drones Club smoking-room. His look of pain was due to the fact that, having now had time to grapple with the problem, he had decided to dispose of this Cynthia once and for all. He proposed to eliminate her for ever from his life. And the elimination of even such a comparative stranger seemed to him to call for a pained look. So he assumed one.

“That,” he said, gravely, “would, I fear, be impossible. It is like you to suggest it, and I cannot tell you how much I appreciate the kindness which has made you interest yourself in my troubles, but it is too late for any reconciliation. Cynthia and I are divorced.”

For a moment the temptation had come to him to kill the woman off with some wasting sickness, but this he resisted as tending towards possible future complications.

He was disturbed to find Eve staring at him in amazement.

“Divorced? But how can you be divorced? It’s only a few days since you and she were in London together.”

Psmith ceased to wonder that Mr. McTodd had had trouble with his wife. The woman was a perfect pest.

“I used the term in a spiritual rather than a legal sense,” he replied. “True, there has been no actual decree, but we are separated beyond hope of reunion.” He saw the distress in Eve’s eyes and hurried on. “There are things,” he said, “which it is impossible for a man to overlook, however broad-minded he may be. Love, Miss Halliday, is a delicate plant. It needs tending, nursing, assiduous fostering. This cannot be done by throwing the breakfast bacon at a husband’s head.”

“What!” Eve’s astonishment was such that the word came out in a startled squeak.

“In the dish,” said Psmith, sadly.

Eve’s blue eyes opened wide.

“Cynthia did that!”

“On more than one occasion. Her temper in the mornings was terrible. I have known her lift the cat over two chairs and a settee with a single kick. And all because there were no mushrooms.”

“Cynthia did that! . . . Cynthia . . . why, she was always the gentlest little creature.”

“At school, you mean?”

“Yes.”

“That,” said Psmith, “would, I suppose, be before she had taken to drink.”

“Taken to drink!”

Psmith was feeling happier. A passing thought did come to him that all this was perhaps a trifle rough on the absent Cynthia, but he mastered the unmanly weakness. It was necessary that Cynthia should suffer in the good cause. Already he had begun to detect in Eve’s eyes the faint dawnings of an angelic pity, and pity is recognized by all the best authorities as one of the most valuable emotions which your wooer can awaken.

“Drink!” Eve repeated, with a little shudder.

“We lived in one of the dry provinces of Canada, and, as so often happens, that started the trouble. From the moment when she installed a private still her downfall was swift. I have seen her, under the influence of home-brew, rage through the house like a devastating cyclone . . . I hate speaking like this of one who was your friend,” said Psmith, in a low, vibrating voice. “I would not tell these things to anyone but you. The world, of course, supposes that the entire blame for the collapse of our home was mine. I took care that it should be so. The opinion of the world matters little to me. But with you it is different. I should not like you to think badly of me, Miss Halliday. I do not make friends easily . . . I am a lonely man . . . but somehow it has seemed to me since we met that you and I might be friends.”

Eve stretched her hand out impulsively.

“Why, of course!”

Psmith took her hand and held it far longer than was, strictly speaking, necessary.

“Thank you,” he said. “Thank you.”

He turned the nose of the boat to the shore and rowed slowly back.

TO Psmith five minutes later, as he sat in his room smoking a cigarette and looking dreamily out at the distant hills, there entered the Hon. Frederick Threepwood, who, having closed the door behind him, tottered to the bed and uttered a deep and discordant groan. Psmith, his mind thus rudely wrenched from pleasant meditations, turned and regarded the gloomy youth with disfavour.

“At any other time, Comrade Threepwood,” he said, politely, but with firmness, “certainly. But not now. I am not in the vein.”

“What?” said the Hon. Freddie, vacantly.

“I say that at any other time I shall be delighted to listen to your farmyard imitations, but not now. At the moment I am deep in thoughts of my own, and I may say frankly that I regard you as more or less of an excrescence. I want solitude, solitude. I am in a beautiful reverie, and your presence jars upon me somewhat profoundly.”

The Hon. Freddie ruined the symmetry of his hair by passing his fingers feverishly through it.

“Don’t talk so much! I never met a fellow like you for talking.” Having rumpled his hair to the left, he went through it again and rumpled it to the right. “I say, do you know what? You’ve jolly well got to clear out of here quick!” He got up from the bed and approached the window. Having done which, he bent towards Psmith and whispered in his ear. “The game’s up!”

(Another long instalment of this splendid story will appear in our next issue.)

Notes:

See Part 1 for general notes about this edition.

Editorial choices for this edition:

Where this version has an exclamation point in “It shines on that wonderful brow of his, doesn’t it!” all other editions have a question mark, so this appears to be a choice by the Grand editor.

Where this version has “she was loth to believe” other versions have the spelling “loath”; this seems a choice made by the Grand editor.

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine omitted closing quotation mark in “Well, well,” said Psmith, indulgently…

Magazine had a period rather than a question mark in “imagine that she is a detective?”

Magazine had “He stopped and picked up a large flower-pot” (as did US magazine), but we prefer the reading “stooped” of US and UK first editions, assuming this to be a mistake in the typescript sent to the magazines.

Magazine had period rather than comma after “note of gentleness in her voice”; corrected to follow other editions.

Magazine capitalized “Try” instead of “try to bring you together” as in other editions.

Magazine capitalized “But” instead of “but somehow it has seemed to me” as in other editions.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums