The Humorist, December 6, 1930

EVERY now and then a writer in one of the magazines will ask: “What has become of the Home?” and then other writers reply that the Home has disappeared, and it is not unlikely that some of them will tap a fruity line of sentiment on the subject of the Home.

Opinions differ as to what it was that slew the Home. Some trace its decease to the improved facilities for travel. There is reason to think that landlords had something to do with it. They always objected to children. As the secret of modern life is to be on good terms with the landlord, children naturally become obsolete.

MORE probably, however, the disappearance of the Home was directly due to the custom of taking family breakfast. This was the real cause of dissolution. The increased facilities for travel merely enabled the sufferers to get away, they having previously been forced to choose between staying on or walking off.

It was that fact that made the Home so impregnable in the early days of civilization. It was a little community cut off from the world. The only horse attached to the establishment belonged to Father, and he kept a hawklike eye on it. You had to trudge along on your own feet, if you wished to shake off the family, and, even if you did, you were bound to run into some other family who would adopt you, thus starting all the trouble over again.

It was that fact that made the Home so impregnable in the early days of civilization. It was a little community cut off from the world. The only horse attached to the establishment belonged to Father, and he kept a hawklike eye on it. You had to trudge along on your own feet, if you wished to shake off the family, and, even if you did, you were bound to run into some other family who would adopt you, thus starting all the trouble over again.

You were, in a word, all dressed up and no place to go. So you just set your teeth, and endured it. There was no getting away from the family breakfast in those days.

People write lightly about family breakfast, just as he jests at scars who never felt a wound. I have just been reading a Book of Etiquette, written by a woman who obviously knows nothing of the horrors of these old-time feasts. In the section devoted to Home Etiquette, she says, “Busy as you may be, it is only a small compliment to your household to sit down to the family breakfast with an air of good-will towards everybody.”

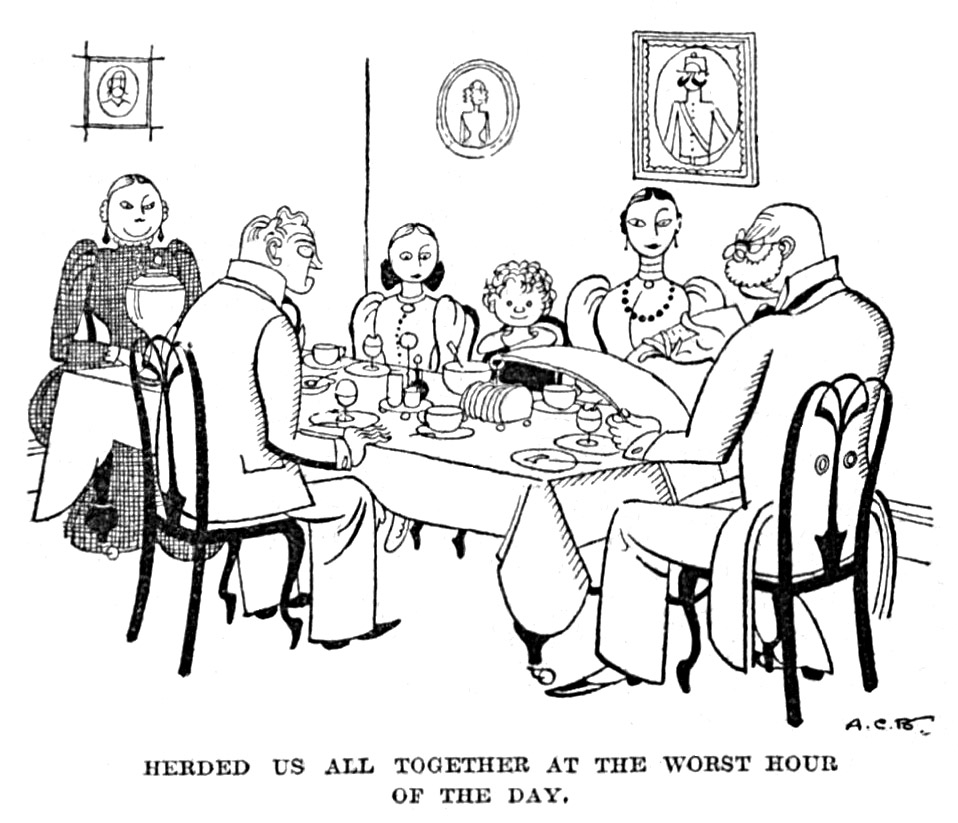

THERE speaks one who has never staggered into the dining-room with one of those early morning headaches and gazed across the table at the repulsive, semi-human countenances of parents, brothers, and sisters. There they sit, the brutes! eating their eggs and bacon, and you must watch them and even exchange remarks with them.

To be expected to do this is too much. To be expected to do this “with an air of good-will towards everybody” is much too much. If one gets through the meal without any definitely homicidal thoughts, one has done all that can reasonably be asked.

There may be those who spring from their beds with a gay song upon their lips and greet the new day with rollicking humour. To these, if they exist, breakfast is a meal like other meals, and may safely be shared with their species.

But to most of us breakfast is not so much a meal as a kind of painful restoration of vitality. It is the crucial moment of the day. We may pull through, or we may not. We are able to tell more certainly after we have had three cups of coffee and absorbed the morning’s news.

Meanwhile, absolute quiet and seclusion is essential. The man who would expect us to exhibit airs of good-will and even engage in conversation would demand sparkling small talk from a Prussian Uhlan.

The Home has disappeared because it would not realize this vital truth. It herded us all together at the worst hour of the day. It had no consideration for the weakness of the flesh.

HOW different is the near-Home which has superseded it. The morning sun shines brightly in on an empty dining-room. Father has had his cold coffee and under-boiled egg and has gone off to business. John, the eldest son, a little fatigued from dancing till six a.m., is breakfasting in bed. Mabel, the daughter, who was playing bridge last night and got home just before John, has yet to be aroused from her refreshing slumber. Mother is out of town. And over the entire establishment broods a sort of cosy peace.

How different from the dark days when Mother sat entrenched behind the coffee-urn, while Father burrowed like a rabbit into the morning paper, and the chicks kicked each other under the table and made personal remarks in bitter undertones.

If home life has survived at all it is in the country. It was for that reason that I recently announced my intention of settling in the country. The principal comment of my friends was that I should find it dull. Dull! I am becoming a nervous wreck. My ganglions are vibrating like a tuning-fork.

I was bitten by a dog, run over by a bicycle, and deprived of a bath, all within the space of twenty-four hours.

The charm of the country is that you never know what is going to happen next. In the city everything is orderly and expected. In the city you know that if you signal to a ’bus to stop, it will go on; if you ask the waiter for lobster he will bring you chicken; if you buy an orchestra stall, it will be behind a pillar.

BUT in the country you cannot make your calculations ahead. The dog that fawns on you on Monday night is quite likely to pin you by the ankle on Tuesday morning. And so with all the other flora and fauna of the countryside. There is no relying on them.

Have you ever realized the charm of going to bed with the sporting chance that you may not be able to wash next day? Only a dweller in the country can understand the thrill of seeing water actually emerging from a tap. It is like the climax of an absorbing drama.

One morning, aqua pura in large quantities; next morning just a gurgle and nothing more. The morning tub in the country combines the medicinal properties of Carlsbad with the fiercer gambling excitements of Monte Carlo.

There is an elasticity about the rule of the road as regards vehicular traffic in these parts which prevents life from ever becoming dull. To bicycle anywhere, except on the footpath, is considered bad form, especially after dark. Lamps are not worn, and bells have gone out of fashion.

To wander, therefore, when dusk has fallen, is to experience all the delights of a charge of cavalry, and some notable attempts to lower the standing long-jump record have recently been made in the neighbourhood.

These footpath-riders have a certain excuse for their actions, in that a band of able and energetic signori, armed with pickaxes, have lately descended upon the place, and are converting the high roads into trenches.

These footpath-riders have a certain excuse for their actions, in that a band of able and energetic signori, armed with pickaxes, have lately descended upon the place, and are converting the high roads into trenches.

But I do not resent their activities, for they provide me with an admirable form of exercise. I know no finer method of getting up an appetite for lunch than to sit on a gate with a pipe and watch a score of men breaking up a road. Sometimes, when the foreman has been particularly vigilant, I have staggered home, hardly able to put one foot before the other.

Yes, it is a tense, restless life, this that I have chosen.

Macbeth alone is enough to keep one from stagnating. He is a small smoky-blue kitten who has adopted me, and I call him Macbeth because he murders sleep.

Try as I may, I cannot arrange my hours of rest to coincide with his. If I go to bed at nine-thirty, so as to be able to rise with him at six, he selects that night for sitting up till the small hours. If I sit up, he wants to turn in at eight, with the idea of starting the day at about five in the morning.

Just as I have settled down to rest, and am dozing off, from the porch outside comes his well-known mew. I rise and admit him. He curls up, to all appearances in for the night. An hour later he is demanding to be let out again with all the passionate energy of a prisoned soul struggling to be free.

Such is life in the country—a pulsating affair. I am growing thin, and there are dark circles under my eyes, but I am glad I came. The hermit’s life teaches resource.

In the absence of ’buses one re-discovers the lost art of walking. One comes to realize that the day really begins earlier than ten o’clock, and that nine-thirty can be quite a good bedtime.

The country has developed in me a new attitude towards life. I find myself more disposed to look with kindliness and tolerance upon those whom I know to be my inferiors—mentally, physically, and otherwise. Indeed, I am almost ready to accept the idea of the essential Brotherhood of Man, an idea which, in the city, I regarded as distasteful—not to say vulgar.

Yes, there are worse things than home life in the country.

A revised version of “Thoughts on Home Life” from 1914.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums