Liberty, August 7, 1926

THE conversation in the bar-parlor of the Anglers’ Rest had drifted round to the subject of the Arts; and somebody asked if the film serial, The Vicissitudes of Vera, which they were showing down at the Bijou Dream, was worth seeing.

“It’s very good,” said Miss Postlethwaite, our courteous and efficient barmaid, who is a prominent first-nighter. “It’s about a professor who gets a girl into his toils and tries to turn her into a lobster.”

“Tries to turn her into a lobster!” echoed we, surprised.

“Yes, sir. Into a lobster. It seems he collected thousands and thousands of lobsters, and mashed them up, and boiled down the juice from their glands, and was just going to inject it into Vera Dalrymple’s spinal column, when Jack Frobisher broke into the house and stopped him.”

“Why did he do that?”

“Because he didn’t want the girl he loved to be turned into a lobster.”

“What we mean,” said we, “is, why did the professor want to turn the girl into a lobster?”

“He had a grudge against her.”

This seemed plausible, and we thought it over for a while. Then one of the company shook his head disapprovingly.

“I don’t like stories like that,” he said. “They aren’t true to life.”

“Pardon me, sir,” said a voice. And we were aware of Mr. Mulliner in our midst.

“Excuse me interrupting what may be a private discussion,” said Mr. Mulliner; “but I chanced to overhear the recent remarks, and you, sir, have opened up a subject on which I happen to hold strong views—to wit, the question of what is, and what is not, true to life.

“How can we, with our limited experience, answer that question? For all we know, at this very moment hundreds of young women all over the country may be in the process of being turned into lobsters. Forgive my warmth, but I have suffered a good deal from this skeptical attitude of mind that is so prevalent nowadays. I have even met people who refused to believe my story about my brother Wilfred, purely because it was a little out of the ordinary run of the average man’s experience.”

Considerably moved, Mr. Mulliner ordered a hot Scotch with a slice of lemon.

“What happened to your brother Wilfred? Was he turned into a lobster?”

“No,” said Mr. Mulliner, fixing his honest blue eyes on the speaker, “he was not. It would be perfectly easy for me to pretend that he was turned into a lobster; but I have always made it a practice—and I always shall make it a practice—to speak nothing but the bare truth. My brother Wilfred simply had a rather curious adventure . . .”

MY brother Wilfred [said Mr. Mulliner] is the clever one of the family. Even as a boy he was always messing about with chemicals, and at the university he devoted his time entirely to research. The result was that while still a very young man he had won an established reputation as the inventor of what are known to the trade as Mulliner’s Magic Marvels—a general term embracing the Raven Gypsy Face Cream, the Snow of the Mountains Lotion, and many other preparations, some designed exclusively for the toilet, others of a curative nature, intended to alleviate the many ills that flesh is heir to.

Naturally, he was a very busy man; and it is to this absorption in his work that I attribute the fact that, though—like all the Mulliners—a man of striking personal charm, he had reached his thirty-first year without ever having been involved in an affair of the heart. I remember him telling me once that he simply had no time for girls.

But we all fall sooner or later, and these strong, concentrated men harder than any. While taking a brief holiday one year at Cannes, he met a Miss Angela Purdue, who was staying at his hotel, and she bowled him over completely.

She was one of these jolly, outdoor girls; and Wilfred has told me that what attracted him first about her was her wholesome, sunburned complexion. In fact, he told Miss Purdue the same thing when, shortly after he had proposed and been accepted, she asked him in her girlish way what it was that had first made him begin to love her.

“It’s such a pity,” said Miss Purdue, “that the sunburn fades so soon. I do wish I knew some way of keeping it.”

Even in his moments of holiest emotion Wilfred never forgot that he was a business man.

“You should try Mulliner’s Raven Gypsy Face Cream,” he said. “It comes in two sizes—the small (or half-crown) jar, and the large jar at seven shillings and sixpence. The large jar contains three and a half times as much as the small jar. It is applied nightly with a small sponge before retiring to rest. Testimonials have been received from numerous members of the aristocracy and may be examined at the office by any bona fide inquirer.”

“Is it really good?”

“I invented it,” said Wilfred simply.

She looked at him adoringly.

“How clever you are! Any girl ought to be proud to marry you.”

“Oh, well!” said Wilfred, with a modest wave of his hand.

“All the same, my guardian is going to be terribly angry when I tell him we’re engaged.”

“Why?”

“I inherited the Purdue millions when my uncle died, you see, and my guardian has always wanted me to marry his son Percy.”

Wilfred kissed her fondly and laughed a defiant laugh.

“Jer mong feesh der selar,” he said lightly, having practically mastered the French language during his two weeks at the hotel.

BUT, some days after his return to London, whither the girl had preceded him, he had occasion to recall her words. As he sat in his study, musing on a preparation to cure the pip in canaries, a card was brought to him.

“Sir Jasper ffinch-ffarrowmere, Bart.,” he read.

The name was strange to him.

“Show the gentleman in,” he said.

And presently there entered a very stout man with a broad, pink face. It was a face whose natural expression should, Wilfred felt, have been jovial, but at the moment it was grave.

“Sir Jasper Finch-Farrowmere?” said Wilfred.

“ffinch-ffarrowmere,” corrected the visitor, his sensitive ear detecting the capital letters.

“Ah, yes. You spell it with two small f’s.”

“Four small f’s.”

“And to what do I owe the honor—?”

“I am Angela Purdue’s guardian.”

“How do you do? A whisky-and-soda?”

“I thank you, no. I am a total abstainer. I found that alcohol had a tendency to increase my weight, so I gave it up. I have also given up butter, potatoes, soups of all kinds, and— However,” he broke off, the fanatic gleam that comes into the eyes of all fat men who are describing their system of diet fading away, “this is not a social call, and I must not take up your time with idle talk. I have a message for you, Mr. Mulliner. From Angela.”

“Bless her!” said Wilfred. “Sir Jasper, I love that girl with a fervor that increases daily.”

“Is that so?” said the baronet. “Well, what I came to say was, it’s all off.”

“What!”

“All off. She sent me to say that she had thought it over and wanted to break the engagement.”

Wilfred’s eyes narrowed. He had not forgotten what Angela had said about this man wanting her to marry his son. He gazed piercingly at his visitor, no longer deceived by the superficial geniality of his appearance. He had read too many detective stories where the fat, jolly, red-faced man turns out a fiend in human shape, to be a ready victim to appearances.

“Indeed?” he said coldly. “I should prefer to have this information from Miss Purdue’s own lips.”

“She won’t see you. But, anticipating this attitude on your part, I brought a letter from her. You recognize the writing?”

WILFRED took the letter. Certainly, the hand was Angela’s, and the meaning of the words he read unmistakable. Nevertheless, as he handed the missive back there was a hard smile on his face.

“There is such a thing as writing a letter under compulsion,” he said.

The baronet’s pink face turned mauve.

“What do you mean, sir?”

“What I say.”

“Are you insinuating—?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Pooh, sir!”

“Pooh to you!” said Wilfred. “And, if you want to know what I think, you poor ffish, I believe your name is spelled with a capital F, like anybody else’s.”

Stung to the quick, the baronet turned on his heel and left the room without uttering another word.

Although he had given up his life to chemical research, Wilfred Mulliner was no mere dreamer. He could be the man of action when necessity demanded. Scarcely had his visitor left when he was on his way to the Senior Test Tubes, the famous chemists’ club in St. James’s. There, consulting Kelly’s County Families, he learned that Sir Jasper’s address was ffinch Hall in Yorkshire. He had found out all he wanted to know. It was at ffinch Hall, he decided, that Angela must now be immured.

For that she was being immured somewhere, he had no doubt. That letter, he was positive, had been written by her under stress of threats. The writing was Angela’s, but he declined to believe that she was responsible for the phraseology and sentiments. He remembered reading a story where the heroine was forced into courses she would not otherwise have contemplated by the fact that somebody was standing over her with a flask of vitriol. Possibly this was what the bounder of a baronet had done to Angela.

Considering this possibility, he did not blame her for what she had said about him, Wilfred, in the second paragraph of her note. Nor did he reproach her for signing herself “Yrs truly, A. Purdue.” Naturally, when baronets are threatening to pour vitriol down her neck, a refined and sensitive young girl cannot pick her words. This sort of thing must of necessity interfere with the selection of the mot juste.

THAT afternoon Wilfred was in a train on his way to Yorkshire. That evening he was in the ffinch Arms in the village of which Sir Jasper was the squire. That night he was in the gardens of ffinch Hall, prowling softly round the house, listening.

And presently, as he prowled, there came to his ears from an upper window a sound that made him stiffen like a statue and clench his hands till the knuckles stood out white under the strain. It was the sound of a woman sobbing.

Wilfred spent a sleepless night, but by morning he had formed his plan of action. I will not weary you with a description of the slow and tedious steps by which he first made the acquaintance of Sir Jasper’s valet, who was an habitue of the village inn, and then by careful stages won the man’s confidence with friendly words and beer. Suffice it to say that, about a week later, Wilfred had induced this man with bribes to leave suddenly on the plea of an aunt’s illness, supplying—so as to cause his employer no inconvenience—a cousin to take his place.

This cousin, as you will have guessed, was Wilfred himself—but a very different Wilfred from the dark-haired, cleancut young scientist who had revolutionized the world of chemistry a few months before by proving that H2O + b3g4z7 – m9z8 = g6f5p3x.

BEFORE leaving London on what he knew would be a dark and dangerous enterprise, Wilfred had taken the precaution of calling in at a well known costumier’s and buying a red wig. He had also purchased a pair of blue spectacles. But for the role that he had now undertaken these were, of course, useless. A blue-spectacled valet could not but have aroused suspicion in the most guileless baronet.

All that Wilfred did, therefore, in the way of preparation, was to don the wig, shave off his mustache, and treat his face to a light coating of the Raven Gypsy Face Cream.

This done, he set out for ffinch Hall.

Externally, ffinch Hall was one of those gloomy, somber country houses that seem to exist only for the purpose of having horrid crimes committed in them. Even in his brief visit to the grounds, Wilfred had noticed fully half a dozen places that seemed incomplete without a cross indicating the spot where body was found by the police. It was the sort of house where ravens croak in the front garden just before the death of the heir and shrieks ring out from behind barred windows in the night.

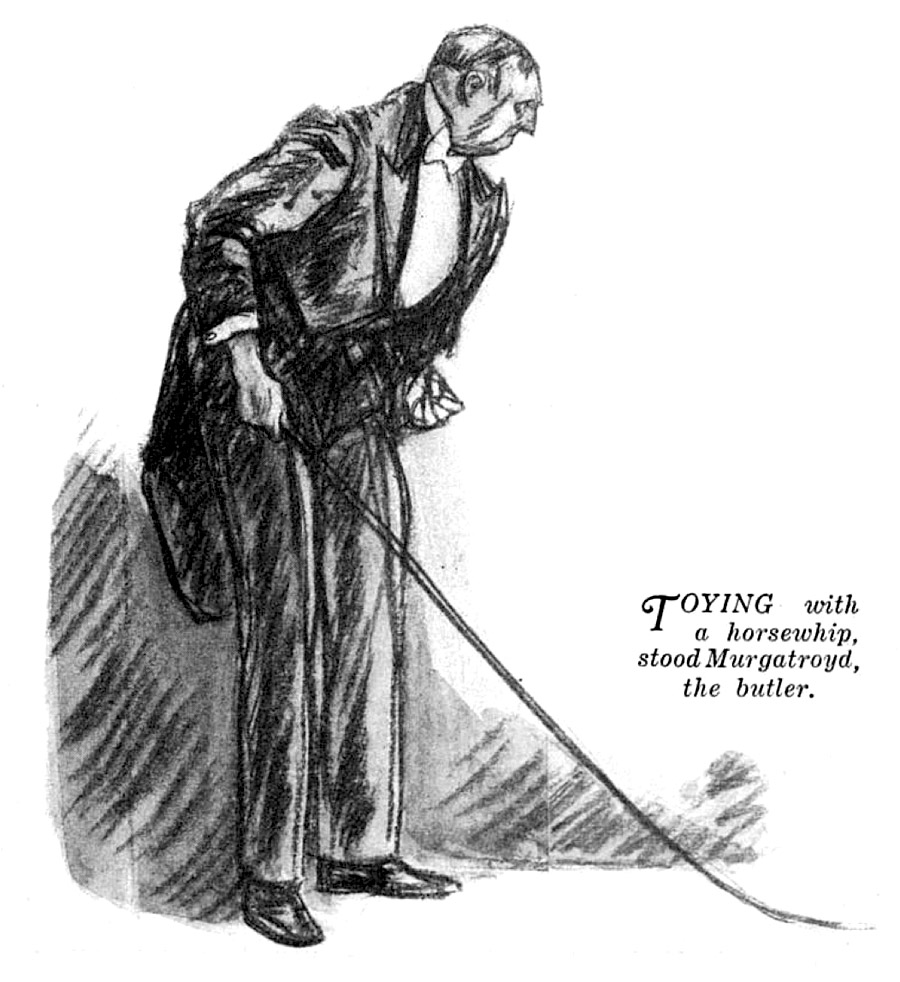

Nor was its interior more cheerful. And as for the personnel of the domestic staff, that was less exhilarating than anything else about the place. It consisted of an aged cook who, as she bent over her caldrons, looked like something out of a traveling company of Macbeth touring the smaller towns of the North; and of Murgatroyd, the butler, a huge, sinister man with a cast in one eye and an evil light in the other.

Many men, under these conditions, would have been daunted. But not Wilfred Mulliner. Apart from the fact that, like all the Mulliners, he was as brave as a lion, he had come expecting something of this nature.

He settled down to his duties and kept his eyes open; and before long his vigilance was rewarded.

One day, as he lurked around the dimly lit passageways, he saw Sir Jasper coming up the stairs with a laden tray in his hands. It contained a toast-rack, a half-bot of white wine, pepper, salt, veg, and in a covered dish something that Wilfred, sniffing cautiously, decided was a cutlet.

Lurking in the shadows, he followed the baronet to the top of the house.

SIR JASPER paused at a door on the second floor. He knocked. The door opened, a hand was stretched forth, the tray vanished, the door closed, and the baronet moved away.

So did Wilfred. He had seen what he had wanted to see, discovered what he had wanted to discover. He returned to the servants’ hall, and, under the gloomy eyes of Murgatroyd, began to shape his plans.

“Where you been?” demanded the butler suspiciously.

“Oh, hither and thither,” said Wilfred, with a well assumed airiness.

Murgatroyd directed a menacing glance at him.

“You’d better stay where you belong,” he said, in his thick, growling voice. “There’s things in this house that don’t want seeing.”

“Oh!” agreed the cook, dropping an onion in the caldron.

Wilfred could not repress a shudder.

BUT, even as he shuddered, he was conscious of a certain relief. At least, he reflected, they were not starving his darling. That cutlet had smelled uncommonly good, and if the bill of fare were always maintained at this level she had nothing to complain of in the catering.

But his relief was short-lived. What, after all, he asked himself, are cutlets to a girl who is imprisoned in a locked room of a sinister country house and is being forced to marry a man she does not love? Virtually nothing. When the heart is sick, cutlets merely alleviate; they do not cure. Fiercely Wilfred told himself that, come what might, few days should pass before he found the key to that locked door and bore away his love to freedom and happiness.

The only obstacle in the way of this scheme was that it was plainly going to be a matter of the greatest difficulty to find the key. That night, when his employer dined, Wilfred searched his room thoroughly. He found nothing. The key, he was forced to conclude, was kept on the baronet’s person.

Then how to secure it?

It is not too much to say that Wilfred Mulliner was nonplused. The brain that had electrified the world of science by discovering that if you mixed a stiffish oxygen with potassium and added a splash of trinitrotoluol and a spot of old brandy, you got something that could be sold in America as champagne at a hundred and fifty dollars the case, had to confess itself baffled.

TO attempt to analyze the young man’s emotions, as the next week dragged itself by, would be merely morbid. Life cannot, of course, be all sunshine; and in relating a story like this, which is a slice of life, one must pay as much attention to shade as to light. Nevertheless, it would be tedious were I to describe to you in detail the soul torments that afflicted Wilfred Mulliner as day followed day and no solution of the problem presented itself.

You are all intelligent men, and you can picture to yourselves how a high-spirited young fellow, deeply in love, must have felt, knowing that the girl he loved was languishing in what virtually amounted to a dungeon—though situated on an upper floor—and chafing at his inability to set her free.

His eyes became sunken. His cheek bones stood out. He lost weight. And so noticeable was this change in his physique that Sir Jasper ffinch-ffarrowmere commented on it one evening in tones of unconcealed envy.

“How the devil, Straker,” he said—for this was the pseudonym under which Wilfred was passing—“do you manage to keep so thin? Judging by the weekly books, you eat like a starving Eskimo, and yet you don’t put on weight. Now, I, in addition to knocking off butter and potatoes, have started drinking hot unsweetened lemon juice each night before retiring, and yet, damme,” he said—for, like all baronets, he was careless in his language—“I weighed myself this morning, and I was up another six ounces. What’s the explanation?”

“Yes, Sir Jasper,” said Wilfred mechanically.

“What the devil do you mean, ‘yes, Sir Jasper’?”

“No, Sir Jasper.”

The baronet wheezed plaintively.

“I’ve been studying this matter closely,” he said, “and it’s one of the seven wonders of the world. Have you ever seen a fat valet? Of course not. Nor has anybody else. There is no such thing as a fat valet. And yet, there is scarcely a moment during the day when a valet is not eating.

“He rises at six-thirty, and at seven is having coffee and buttered toast.

“At eight he breakfasts off porridge, cream, eggs, bacon, jam, bread and butter, more eggs, more bacon, more jam, more tea, and more bread and butter, finishing up with a slice of cold ham and a sardine.

“At eleven o’clock he has his ‘elevenses,’ consisting of coffee, cream, more bread and more butter.

“At one, luncheon—a hearty meal, replete with every form of starchy food and lots of beer. If he can get at the port, he has port.

“At three, a snack. At four, another snack. At five, tea and buttered toast.

“At seven, dinner—probably with floury potatoes and certainly with lots more beer.

“At nine, another snack. And at ten-thirty he retires to bed, taking with him a glass of milk and a plate of biscuits to keep himself from getting hungry in the night.

“And yet, he remains as slender as a string bean; while I, who have been dieting for years, tip the beam at two hundred and seventeen pounds and am growing a third and supplementary chin. These are mysteries, Straker.”

“Yes, Sir Jasper.”

“Well, I’ll tell you one thing,” said the baronet. “I’m getting down one of those indoor Turkish bath cabinet affairs from London, and if that doesn’t do the trick I give up the struggle.”

The indoor Turkish bath duly arrived and was unpacked; and it was some three nights later that Wilfred, brooding in the servants’ hall, was roused from his reverie by Murgatroyd.

“Here,” said Murgatroyd; “wake up. Sir Jasper’s calling you.”

“Calling me what?” asked Wilfred, coming to himself with a start.

“Calling you very loud,” growled the butler.

It was indeed so. From the upper regions of the house there was proceeding a series of sharp yelps, evidently those of a man in mortal stress.

WILFRED was reluctant to interfere in any way if, as seemed probable, his employer was dying in agony; but he was a conscientious man, and it was his duty, while in this sinister house, to perform the work for which he was paid.

He hurried up the stairs, and, entering Sir Jasper’s bedroom, perceived the baronet’s crimson face protruding from the top of the indoor Turkish bath.

“So you’ve come at last!” cried Sir Jasper. “Look here, when you put me into this infernal contrivance just now, what did you do to the dashed thing?”

“Nothing beyond what was indicated in the printed pamphlet accompanying the machine, Sir Jasper. Following the instructions, I slid Rod A into Groove B, fastening with Catch C.”

“Well, you must have made a mess of it somehow. The thing’s stuck! I can’t get out.”

“You can’t?” cried Wilfred.

“NO. And the bally apparatus is getting considerably hotter than the hinges of the inferno.” (I must apologize for Sir Jasper’s language, but you know what baronets are.) “I’m being cooked to a crisp!”

A sudden flash of light seemed to blaze upon Wilfred Mulliner.

“I will release you, Sir Jasper.”

“Well, hurry up, then.”

“On one condition.” Wilfred fixed him with a piercing gaze. “First, I must have the key.”

“There isn’t a key, you idiot. It doesn’t lock. It just clicks when you slide Gadget D into Thingumabob E.”

“The key I require is that of the room in which you are holding Angela Purdue a prisoner.”

“What the devil do you mean? Ouch!”

“I will tell you what I mean, Sir Jasper ffinch-ffarrowmere. I am Wilfred Mulliner.”

“Don’t be an ass. Wilfred Mulliner has black hair. Yours is red. You must be thinking of someone else.”

“This is a wig,” said Wilfred; “by Clarkson.” He shook a menacing finger at the baronet. “You little thought, Sir Jasper ffinch-ffarrowmere, when you embarked on this dastardly scheme, that Wilfred Mulliner was watching your every move. I guessed your plans from the start. And now is the moment when I checkmate them. Give me that key, you fiend.”

“ffiend,” corrected Sir Jasper automatically.

“I am going to release my darling—to take her away from this dreadful house—to marry her by special license as soon as it can legally be done!”

In spite of his sufferings, a ghastly laugh escaped Sir Jasper’s lips.

“You are, are you?”

“I am.”

“Yes, you are!”

“Give me the key.”

“I haven’t got it, you chump. It’s in the door.”

“Ha, ha!”

“It’s no good saying ‘Ha, ha!’ It is in the door; on Angela’s side of the door.”

“A likely story! But I cannot stay here, wasting time. If you will not give me the key, I shall go up and break in the door.”

“Do!” Once more the baronet laughed like a tortured soul. “And see what she’ll say.”

Wilfred could make nothing of this last remark. He could, he thought, imagine very clearly what Angela would say. He could picture her sobbing on his chest, murmuring that she knew he would come, that she had never doubted him for an instant. He leaped for the door.

“Here! Hi! Aren’t you going to let me out?”

“Presently,” said Wilfred. “Keep cool.”

He raced up the stairs.

“A

NGELA,” he cried, pressing his lips against the panel. “Angela!”

“A

NGELA,” he cried, pressing his lips against the panel. “Angela!”

“Who’s that?” answered a well remembered voice from within.

“It is I—Wilfred. I am going to burst open the door. Stand clear of the gates.”

He drew back a few paces, and hurled himself at the woodwork. There was a grinding crash as the lock gave. And Wilfred, staggering on, found himself in a room so dark that he could see nothing.

“Angela, where are you?”

“I’m here. And I’d like to know why you are, after that letter I wrote you. Some men,” continued the strangely cold voice, “do not seem to know how to take a hint.”

Wilfred staggered and would have fallen had he not clutched at his forehead.

“That letter?” he stammered. “You surely didn’t mean what you wrote in that letter?”

“I meant every word, and I wish I had put in more.”

“But—but—but—but don’t you love me, Angela?”

A hard, mocking laugh rang through the room.

“Love you? Love the man who recommended me to try Mulliner’s Raven Gypsy Face Cream?”

“What do you mean?”

“I will tell you what I mean. Wilfred Mulliner, look on your handiwork!”

The room became suddenly flooded with light. And there, standing with her hand on the switch, stood Angela—a queenly, lovely figure, in whose radiant beauty the sternest critic would have noted but one flaw: the fact that she was piebald.

Wilfred gazed at her with adoring eyes. Her face was partly brown and partly white, and on her snowy neck there were patches of sepia that looked like the thumb-prints you find on the pages of books in the Free Library. But he thought her the most beautiful creature he had ever seen. He longed to fold her in his arms, and but for the fact that her eyes told him that she would undoubtedly land an uppercut on him if he tried it, he would have done so.

“Yes,” she went on. “This is what you have made of me, Wilfred Mulliner—you and that awful stuff you call the Raven Gypsy Face Cream.

“I took your advice and bought one of the large jars at seven-and-six, and see the result! Barely twenty-four hours after the first application, I could have walked into any circus and named my own terms as the Spotted Princess of the Fiji Islands.

“I fled here, to my childhood home, to hide myself. And the first thing that happened”—her voice broke—“was that my favorite hunter shied at me and tried to bite pieces out of his manger; while Ponto, my little dog, whom I have reared from a puppy, caught one sight of my face and is now in the hands of the vet and unlikely to recover. And it was you, Wilfred Mulliner, who brought this curse upon me!”

Many men would have wilted beneath those searing words, but Wilfred Mulliner merely smiled with infinite compassion and understanding.

“It is quite all right,” he said. “I should have warned you, sweetheart, that this occasionally happens in cases where the skin is exceptionally delicate and finely textured. It can be speedily remedied by an application of the Mulliner Snow of the Mountains Lotion, four shillings the medium-sized bottle.”

“Wilfred! Is this true?”

“Perfectly true, dearest. And is this all that stands between us?”

“No!” shouted a voice of thunder.

Wilfred wheeled sharply. In the doorway stood Sir Jasper ffinch-ffarrowmere. He was swathed in a bath towel, what was visible of his person being a bright crimson. Behind him, toying with a horsewhip, stood Murgatroyd, the butler.

“You didn’t expect to see me, did you?”

“I certainly,” replied Wilfred severely, “did not expect to see you in a lady’s presence in a costume like that.”

“Never mind my costume!” Sir Jasper turned. “Murgatroyd, do your duty!”

The butler, scowling horribly, advanced into the room.

“Stop!” screamed Angela.

“I haven’t begun yet, miss,” said the butler deferentially.

“You shan’t touch Wilfred. I love him.”

“What!” cried Sir Jasper. “After all that has happened?”

“Yes. He has explained everything.”

A grim frown appeared on the baronet’s vermilion face.

“I’ll bet he hasn’t explained why he left me to be cooked in that infernal Turkish bath! I was beginning to throw out clouds of smoke when Murgatroyd, faithful fellow, heard my cries and came and released me.”

“Though not my work,” added the butler.

Wilfred eyed him steadily.

“If,” he said, “you used Mulliner’s Reduc-o, the recognized specific for obesity, whether in the tabloid form at three shillings the tin, or as a liquid at five-and-six the flask, you would have no need to stew in Turkish baths. Mulliner’s Reduc-o, which contains no injurious chemicals, but is compounded purely of health-giving herbs, is guaranteed to remove excess weight, steadily and without weakening after effects, at the rate of two pounds a week. As used by the nobility.”

The glare of hatred faded from the baronet’s eyes.

“Is that a fact?” he whispered.

“It is.”

“You guarantee it?”

“All the Mulliner preparations are fully guaranteed.”

“My boy!” cried the baronet. He shook Wilfred by the hand. “Take her,” he said brokenly. “And with her my b-blessing.”

A discreet cough sounded in the background.

“You haven’t anything, by any chance, sir,” asked Murgatroyd, “that’s good for lumbago?”

“Mulliner’s Ease-o will cure the most stubborn case in six days.”

“Bless you, sir, bless you!” sobbed Murgatroyd. “Where can I get it?”

“At all chemists.”

“It catches me in the small of the back principally, sir.”

“It need catch you no longer,” said Wilfred.

There is little to add. Murgatroyd is now the most lissom butler in Yorkshire. Sir Jasper’s weight is down under the two hundred pounds, and he is thinking of taking up hunting again. Wilfred and Angela are man and wife; and never, I am informed, have the wedding bells of the old church at ffinch village rung out a blither peal than they did on that June morning when Angela, raising to her lover a face on which the brown was as evenly distributed as on an antique walnut table, replied to the clergyman’s question, “Wilt thou, Angela, take this Wilfred?” with a shy “I will.” They now have two bonny bairns—the small, or Percival, at a preparatory school in Sussex and the large, or Ferdinand, at Eton.

HERE Mr. Mulliner, having finished his hot Scotch, bade us farewell and took his departure.

A silence followed his exit. The company seemed plunged in deep thought. Then somebody rose.

“Well, good night, all,” he said. It seemed to sum up the situation.

the end

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine had “H20” in chemical formula; corrected to “H2O” as in other versions.

Magazine had “The bulter, scowling horribly”; corrected to “butler”

Magazine had “And with her my bblessing”; corrected to “b-blessing” as in book editions.

Notes:

“Jer mong feesh der selar,” he said lightly, having practically mastered the French language during his two weeks at the hotel: “Je m’en fiche de cela,” French for “I don’t care about that.” The boldface words don’t appear in the UK magazine or either book edition.

a stiffish oxygen with potassium: Presumably an editorial change by Liberty. It is a stiffish oxygen and potassium in the UK magazine and both book editions.

In both US and UK magazines, Sir Jasper got his weight down to “under the two hundred pounds” from his 217-pound starting point which is pretty good going. But for some reason when the story was collected in Meet Mr. Mulliner this passage was re-written so his weight was “down under the fifteen stone” (210 pounds). Not nearly as impressive!

See also our annotations to this story as it appeared in volume form in Meet Mr. Mulliner (1927/28).

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums