Liberty, June 30, 1928

Part Three

HUGO pranced buoyantly up to the table, looking like the Laughing Cavalier clean shaved. He was wearing the unmistakable air of a man who has been to a welterweight boxing contest at the Albert Hall and backed the winner.

“Hullo, Pat,” he said jovially. “Hullo, John. Sorry I’m late. Mitt—if that is the word I want—my dear old friend—I’ve forgotten your name,” he added, turning to his companion.

“Molloy, brother. Thomas G. Molloy.”

Hugo’s dear old friend spoke in a deep, rich voice. He was a fine, handsome, open-faced person in the early forties, with grizzled hair that swept in a wave off a massive forehead. His nationality was plainly American and his aspect vaguely senatorial.

“Molloy,” said Hugo. “Thomas G. And daughter. This is Miss Wyvern. And this is my cousin, Mr. Carroll. And now,” said Hugo, relieved at having finished with the introductions, “let’s try to get a bit of supper.”

The service at the Mustard Spoon is not what it was; but by the simple process of clutching at the coat tails of a passing waiter and holding him till he consented to talk business, Hugo contrived to get fairly rapid action.

Then, after an interval of the rather difficult conversation which usually marks the first stages of this sort of party, the orchestra burst into a sudden torrent of what it evidently mistook for music, and Thomas G. Molloy rose and led Miss Molloy out on to the floor.

“Who are your friends, Hugo?” asked Pat.

“Thos. G.—”

“Yes, I know. But who are they?”

“Well, there,” said Hugo, “you rather have me. I sat next to Thos. at the fight, and I rather took to the fellow. He seemed to me a man full of noble qualities, including a loony idea that Eustace Rodd was some good as a boxer. He actually offered to give me three to one, and I cleaned up substantially at the end of the seventh round.

“After that I naturally couldn’t very well get out of giving the man supper. And as he had promised to take his daughter out tonight, I said bring her along. You don’t mind?”

“Of course not. Though it would have been cozier, just we three.”

“Quite true. But never forget that if it had not been for this Thos. you would not be getting the jolly good supper which I have now ample funds to supply. You may look on Thos. as practically the founder of the feast.”

He cast a wary eye at his cousin, who was leaning back in his chair with the abstracted look of one in deep thought.

“Has old John said anything to you yet?”

“John? What do you mean? What about?”

“Oh, things in general. Come and dance this. I want to have a very earnest word with you, young Pat. Big things are in the wind.”

“You’re very mysterious.”

“Ah!” said Hugo.

Left alone at the table with nothing to entertain him but his thoughts, John came almost immediately to the conclusion that his first verdict on the Mustard Spoon had been an erroneous one.

Looking at it superficially, he had mistaken it for rather an attractive place; but now, with maturer judgment, he saw it for what it was—a blot on a great city. He disliked the clientele. He disliked the head waiter. He disliked the orchestra. The clientele was flashy and offensive and, as regarded the male element of it, far too given to the use of hair oil.

HE was brooding on the scene in much the same spirit of captious criticism as that in which Lot had once regarded the cities of the plain, when Ben Baermann’s Collegiate Buddies suddenly suspended their cacophony and he saw Pat and Hugo coming back to the table.

But the Buddies had only been crouching, the better to spring. A moment later they were at it again; and Pat, pausing, looked expectantly at Hugo.

Hugo shook his head.

“I’ve just seen Ronnie Fish up in the balcony,” he said. “I positively must go and confer with him. I have urgent matters to discuss with the old leper. Sit down and talk to John. You’ve got lots to talk about. See you anon. And, if there’s anything you want, order it, paying no attention whatever to the prices in the right-hand column. Thanks to Thos., I’m made of money tonight.”

Hugo melted away; Pat sat down; and John, with another abrupt change of mood, decided that he had misjudged the Mustard Spoon. A very jolly little place, when you looked at it in the proper spirit. Nice people, a distinctly lovable head waiter, and as attractive a lot of musicians as he remembered ever to have seen.

He turned to Pat, to seek her confirmation of these views, and, meeting her gaze, experienced a rather severe shock. Her eyes seemed to have frozen over. They were cold and hard. Taken in conjunction with the fact that her nose turned up a little at the end, they gave her face a scornful and contemptuous look.

“Hullo!” he said, alarmed. “What’s the matter?”

“Nothing.”

“Why are you looking like that?”

“Like what?”

“Well—”

JOHN had little ability as a word painter. He could not, on the spur of the moment, give anything in the nature of detailed description of the way Pat was looking. He only knew he did not like it.

“I suppose you expected me to look at you ‘with eyes overrunning with laughter’?”

“Eh?”

“ ‘Archly the maiden smiled, and, with eyes overrunning with laughter, said, in a tremulous voice, “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?” ’ ”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Don’t you know The Courtship of Miles Standish? I thought that must have been where you got the idea. I had to learn chunks of it at school, and even at that tender age I always thought Miles Standish a perfect goop.

“ ‘ “If the great Captain of Plymouth is so very eager to wed me, why does he not come himself, and take the trouble to woo me? If I am not worth the wooing, I surely am not worth the winning!” ’

“And yards more of it. I knew it by heart once. Well, what I want to know is, do you expect my answer direct, or would you prefer that I communicate with your agent?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Don’t you? No? Really?”

“Pat, what’s the matter?”

“Oh, nothing much. When we were dancing just now, Hugo proposed to me.”

A cold hand clutched at John’s heart. He had not a high opinion of his cousin’s fascinations, but the thought of anybody but himself proposing to Pat was a revolting one.

“Oh, did he?”

“Yes, he did. For you.”

“For me? How do you mean, for me?”

“I’m telling you. He asked me to marry you. And very eloquent he was, too. All the people who heard him—and there must have been dozens who did—were much impressed.”

She stopped; and, as far as such a thing is possible at the Mustard Spoon when Ben Baermann’s Collegiate Buddies are giving an encore of My Sweetie Is a Wow, there was silence.

John had flushed a dusky red, and his collar had suddenly become so tight that he had all the sensations of a man who is being garroted. His only coherent thought was a desire to follow Hugo up to the balcony, tear him limb from limb, and scatter the fragments on to the tables below.

Pat was the first to find speech. She spoke quickly, stormily:

“I can’t understand you, Johnny! You never used to be such a jellyfish. You did have a mind of your own once. But now— I believe it’s living at Rudge all the time that has done it. You’ve got lazy and flabby. It’s turned you into a vegetable. You just loaf about and go on and on, year after year, having your three fat meals a day and your comfortable rooms and your hot-water bottle at night—”

“I DON’T!” cried John, stung by this monstrous charge from the coma that was gripping him.

“Well, bed socks, then,” amended Pat. “You’ve just let yourself be cosseted and pampered and kept in comfort till the you that used to be there has withered away and you’ve gone blah.

“My dear, good Johnny,” said Pat vehemently, riding over his attempt at speech and glaring at him above a small, perky nose whose tip had begun to quiver, even as it had always done when she lost her temper as a child. “My poor, idiotic, fat-headed Johnny, do you seriously expect a girl to want to marry a man who hasn’t the common, elementary pluck to propose to her for himself and has to get someone else to do it for him?”

“I didn’t!”

“You did.”

“I tell you, I did not.”

“You mean you never asked Hugo to sound me out?”

“Of course not. Hugo is a meddling, officious idiot, and if I had him here now I’d wring his neck.”

He scowled up at the balcony. Hugo, who happened to be looking down at the moment, beamed encouragingly and waved a friendly hand as if to assure his cousin that he was with him in spirit.

Silence, tempered by the low wailing of the Buddy in charge of the saxophone and the unpleasant howling of his college friends, who had just begun to sing the chorus, fell once more.

“This opens up a new line of thought,” said Pat at length. “Our Miss Wyvern appears to have got the wires crossed.” She looked at him meditatively. “It’s funny. Hugo seemed so convinced about the way you felt.”

John’s collar tightened up another half inch, but he managed to get his vocal cords working.

“He was quite right about the way I felt.”

“You mean—really?”

“Yes.”

“You mean you’re—fond of me?”

“Yes.”

“But, Johnny!”

“Damn it, are you blind?” cried John, savage from shame and the agony of harrowed feelings. “Can’t you see? Don’t you know I’ve always loved you? Yes, even when you were a kid.”

“But, Johnny, Johnny, Johnny!” Distress was making Pat’s silver voice almost squeaky. “You can’t have. I was a horrible kid. I did nothing but bully you from morning till night.”

“I liked it.”

“But how can you want me to marry you? We know each other too well. I’ve always looked on you as a sort of brother.”

There are words in the language that are like a knell. Keats considered “forlorn” one of them. John Carroll was of the opinion that “brother” was a second.

“Oh, I know. I was a fool. I knew you would simply laugh at me!”

Pat’s eyes were misty. The tip of her nose no longer quivered, but now it was her mouth that did so. She reached out across the table and her hand rested on his for a brief instant.

“I’m not laughing at you, Johnny, you—you chump. What would I want to laugh at you for? I’m much nearer crying. I’d do anything in the world rather than hurt you. You must know that. You’re the dearest old thing that ever lived. There’s no one on earth I’m fonder of.” She paused. “But this—it—it simply isn’t on the board.”

She was looking at him furtively, taking advantage of the fact that his face was turned away.

IT was odd, she felt, all very odd. If she had been asked to describe the sort of man whom one of these days she hoped to marry, the description, curiously enough, would not have been at all unlike dear old Johnny.

He had the right clean, fit look—she knew she could never give a thought to anything but an outdoor man—and the straightness and honesty and kindliness which she had come, after moving for some years in a world where they were rare, to look upon as the highest of masculine qualities.

Nobody could have been further than John from the little, black-mustached dancing-man type which was her particular aversion, and yet—well, the idea of becoming his wife was just simply too absurd.

But why? What, then, was wrong with Johnny? Simply, she felt, the fact that he was Johnny. Marriage, as she had always envisaged it, was an adventure. Poor, cozy, solid old Johnny would have to display quite another side of himself, if such a side existed, before she could regard it as an adventure to marry him.

“That man,” said John, indicating Mr. Baermann, “looks like a Jewish black beetle.”

Pat was relieved. If by this remark he was indicating that he wished the recent episode to be taken as concluded, she was very willing to oblige him.

“Doesn’t he?” she said. “I don’t know where they can have dug him up from. I think this place has gone down. I don’t like the look of some of these people. What do you think of Hugo’s friends?”

“They seem all right.”

John cast a moody eye at Miss Molloy, a prismatic vision seen fitfully through the crowd. She was laughing, and showing in the process teeth of a flashing whiteness.

“The girl’s the prettiest girl I’ve seen for a long time.”

Pat gave an imperceptible start. She was suddenly aware of a feeling that was remarkably like uneasiness.

“Oh?” she said.

Yes, the feeling was uneasiness. Any other man who at such a moment had said those words she would have suspected of a desire to pique her, to stir her interest by a rather obviously assumed admiration of another. But not John. He was much too honest. If Johnny said a thing, he meant it.

Pat knew quite well that, though she did not want to marry him, she regarded John as essentially a piece of personal property. If he had fallen in love with her, that was, of course, a pity; but it would, she realized, be considerably more of a pity if he ever fell in love with someone else. A Johnny gone out of her life and assimilated into that of another girl would leave a frightful gap.

“Oh?” she said.

The music stopped. The floor emptied. Mr. Molloy and his daughter returned to the table. Hugo remained up in the gallery, in earnest conversation with his old friend Mr. Fish.

RONALD OVERBURY FISH was a pink-faced young man of small stature and extraordinary solemnity. He had been at school with Hugo and also at the university. Eton was entitled to point with pride at both of them, and had only itself to blame if it failed to do so. The same remark applies to Trinity College, Cambridge.

From earliest days Hugo had always entertained for R. O. Fish an intense and lively admiration, and the thought of being compelled to let his old friend down in this matter of the Hot Spot was doing much to mar an otherwise jovial evening.

“I’m most frightfully sorry, Ronnie, old thing,” he said, immediately the first greetings were over. “I sounded the aged relative this afternoon about that business, and there’s nothing doing.”

“No hope?”

“None.”

Ronnie Fish surveyed the dancers below with a grave eye. He removed the stub of his cigarette from its eleven-inch holder, and recharged that impressive instrument.

“Did you reason with the old pest?”

“You can’t reason with my Uncle Lester.”

“I could,” said Mr. Fish.

Hugo did not doubt this. Ronnie, in his opinion, was capable of any feat.

“Yes; but the only trouble is,” he explained, “you would have to do it at long range. I asked if I might invite you down to Rudge, and he would have none of it.”

Ronnie Fish relapsed into silence. It seemed to Hugo, watching him, that that great brain was busy, but upon what train of thought he could not conjecture.

“Who are those people you’re with?” he asked at length.

“The big chap with the fair hair is my cousin John. The girl in green is Pat Wyvern. She lives near us.”

“And the others? Who’s the stately looking bird with the brushed back hair who has every appearance of being just about to address a gathering of constituents on some important point of policy?”

“That’s a fellow named Molloy. Thos. G. I met him at the fight. He’s an American.”

“He looks prosperous.”

“He is not so prosperous as he was before the fight started. I took thirty quid off him.”

“Your uncle, from what you have told me, is pretty keen on rich men, isn’t he?”

“All over them.”

“Then the thing’s simple,” said Ronnie Fish. “Invite this Mulcahy, or whatever his name is, to Rudge, and invite me at the same time. You’ll find that, in the ecstasy of getting a millionaire on the premises, your uncle will forget to make a fuss about my coming. And once I am in, I can talk this business over with him. I’ll guarantee that if I can get an uninterrupted half hour with the old boy I can easily make him see the light.”

A rush of admiration for his friend’s outstanding brain held Hugo silent for a moment. The bold simplicity of the move thrilled him.

“What it amounts to,” continued Ronnie Fish, “is that your uncle is endeavoring to do you out of a vast fortune. I tell you, the Hot Spot is going to be a gold mine. To all practical intents and purposes, he is just as good as trying to take thousands of pounds out of your pocket. I shall point this out to him, and I shall be surprised if I can’t put the thing through. When would you like me to come down?”

“Ronnie,” said Hugo, “this is absolute genius.”

He hesitated. He had no wish to discourage his friend, but he desired to be fair and aboveboard.

“There’s just one thing. Would you have any objection to performing at the village concert?”

“I should enjoy it.”

“They’re sure to rope you in. I thought you and I might do the Quarrel Scene from Julius Cæsar again.”

“Excellent.”

“And this time,” said Hugo generously, “you can be Brutus.”

“No, no,” said Ronnie, moved.

“Yes, yes.”

“Very well. Then fix things up with this American bloke, and leave the rest to me. Shall I like your uncle?”

“No,” said Hugo confidently.

“Ah, well,” said Mr. Fish equably, “I don’t for a moment suppose he’ll like me.”

THE respite afforded to their patrons’ eardrums by the sudden cessation of activity on the part of the Buddies proved of brief duration. Very soon they were at it again, and Mr. Molloy, rising, led Pat gallantly out on to the floor. His daughter, following them with a bright eye as she busied herself with a lip stick, laughed amusedly.

“She little knows!”

John, like Ronnie a short while before, had fallen into a train of thought. From this he now woke with a start to the realization that he was alone with this girl and presumably expected by her to make some effort at being entertaining.

“I beg your pardon?” he said.

Even had he been less preoccupied, he would have found small pleasure in this tête-à-tête.

Miss Molloy—her father addressed her as Dolly—belonged to the type of girl in whose society a diffident man is seldom completely at ease. There hung about her like an aura a sort of hard glitter. Her challenging eyes were of a bright hazel—beautiful but intimidating. She looked supremely sure of herself.

“I was saying,” she explained, “that your girl friend little knows what she has taken on, going out to step with Soapy.”

“Soapy?”

It seemed to John that his companion had momentarily the appearance of being a little confused.

“My father, I mean,” she said quickly. “I call him Soapy.”

“Oh?” said John. He supposed the practice of calling a father by a nickname in preference to the more old-fashioned style of address was the latest fad of the modern girl.

“Soapy,” said Miss Molloy, developing her theme, “is full of sex appeal, but he has two left feet.” She emitted another little gurgle of laughter. “There! Would you just look at him now!”

John was sorry to appear dull, but, seeing Mr. Molloy as requested, he could not see that he was doing anything wrong.

“I’m afraid I don’t know anything about dancing,” he said apologetically.

“At that, you’re ahead of Soapy. He doesn’t even suspect anything. Whenever I get into the ring with him and come out alive, I reckon I’ve broke even. It isn’t so much his dancing on my feet that I mind—it’s the way he jumps on and off that slays me. Don’t you ever hoof?”

“Oh, yes. Sometimes. A little.”

“Well, come and do your stuff, then. I can’t sit still while they’re playing that thing.”

John rose reluctantly. But there was no way of avoiding the ordeal.

He backed her out into midstream, hoping for the best.

Providence was in a kindly mood. By now the floor had become so congested that skill was at a discount. Even the sallow youths with the marcelled hair and the india-rubber legs were finding little scope to do anything but shuffle. This suited John’s individual style. He, too, shuffled—and, playing for safety, found that he was getting along better than he could have expected. His tension relaxed and he became conversational,

“Do you often come to this place?” he asked, resting his partner against the slim back of one of the marcelled hair brigade who, like himself, had been held up in the traffic block.

“I’ve never been here before. And it’ll be a long time before I come again. A more gosh-awful aggregation of yells for help than this gang of whippets,” said Miss Molloy, surveying the company with a critical eye, “I’ve never seen. Look at that dame with the eyeglass.”

“Rather weird,” agreed John.

“A cry for succor,” said Miss Molloy severely. “And why, when you can buy insecticide at any drug store, people let these boys with the shiny hair go around loose beats me.”

John began to warm to this girl. He, too, had felt an idle wonder that somebody did not do something about these youths.

The Buddies had stopped playing; and John, glowing with the strange new spirit of confidence that had come to him, clapped loudly for an encore.

But the Buddies were not responsive. They were sitting, instruments in hand, gazing in a spellbound manner at a square-jawed person in ill fitting dress clothes who had appeared at the side of Mr. Baermann. And the next moment there shattered the stillness a sudden voice that breathed Vine Street in every syllable.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” boomed the voice—proceeding, as nearly as John could ascertain, from close to the main entrance—“will you kindly take your seats.”

“Pinched!” breathed Miss Molloy in his ear. “Couldn’t you have betted on it in a dump like this!”

HER diagnosis was plainly correct. In response to the request, most of those on the floor had returned to their tables, moving with the dull resignation of people to whom this sort of thing has happened before; and, enjoying now a wider range of vision, John was able to see that the room had become magically filled with replicas of the sturdy figure standing beside Mr. Baermann.

They were moving about among the tables, examining with an offensive interest the bottles that stood thereon and jotting down epigrams on the subject in little notebooks.

It was evident that the Mustard Spoon, having forgotten to look at its watch, had committed the amiable error of serving alcoholic refreshment after prohibited hours.

“I might have known,” said Miss Molloy querulously, “that something of the sort was bound to break loose in a dump like this.”

John, like all dwellers in the country as opposed to the wicked inhabitants of cities, was a law-abiding man. Left to himself, he would have followed the crowd and made for his table, there to give his name and address in the sheepish undertone customary on these occasions.

But he was not left to himself. Miss Molloy grasped his arm and pulled him commandingly to a small door that led to the club’s service quarters. It was the one strategic point not yet guarded by a stocky figure with large feet and an eye like a gimlet. To it his companion went like a homing rabbit, dragging him with her.

They passed through; and John, with a resourcefulness of which he was surprised to find himself capable, turned the key in the lock.

“Smooth!” said Miss Molloy approvingly. “Nice work! That’ll hold them for a while.”

It did. From the other side of the door there proceeded a confused shouting, and somebody twisted the handle with a good deal of petulance. But the law had apparently forgotten to bring its ax with it tonight, and nothing further occurred. They made their way down a stuffy passage, came presently to a second door, and, passing through this, found themselves in a back yard fragrant with the scent of old cabbage stalks and dish water.

“Now,” Miss Molloy said briskly, “if you’ll just fetch one of those ash cans and put it alongside that wall and give me a leg-up and help me round that chimney and across that roof and down into the next yard and over another wall or two, I think everything will be more or less jake.”

II

JOHN sat in the lobby of the Lincoln Hotel in Curzon Street. A lifetime of activity and dizzy hustle had passed, but it had all been crammed into just under twenty minutes; and, after seeing his fair companion off in a taxicab, he had made his way to the Lincoln, to ascertain from a sleepy night porter that Miss Wyvern had not yet returned. He was now awaiting her coming.

She came some little while later, escorted by Hugo.

It was a fair summer night, warm and still; but with her arrival a keen east wind seemed to pervade the lobby.

Pat was looking pale and proud, and Hugo’s usually effervescent demeanor had become toned down to a sort of mellow sadness. He had the appearance of a man who has recently been properly ticked off by a woman for Taking Me to Places Like That.

“Oh, hullo, John,” he murmured in a low, bedside voice.

He brightened a little, as a man will who, after a bad quarter of an hour with an emotional girl, sees somebody who may possibly furnish an alternative target for her wrath.

“Where did you get to? Left early to avoid the rush?”

“It was this way—” began John.

But Pat had turned to the desk and was asking the porter for her key. If a female martyr in the rougher days of the Roman Empire had had occasion to ask for a key, she would have done it in just the voice which Pat employed. It was not a loud voice, nor an angry one—just the crushed, tortured voice of a girl who has lost her faith in the essential goodness of humanity.

“You see—” said John.

“Are there any letters for me?” asked Pat.

“No, no letters,” said the night porter. And the unhappy girl gave a little sigh, as if that was just what might be expected in a world where men who had known you all your life took you to Places which they ought to have Seen from the Start were just Drinking Hells, while other men, who also had known you all your life—and, what was more, professed to love you—skipped through doors in the company of flashy women and left you to be treated by the police as if you were a common criminal.

“What happened,” said John, “was this.”

“Good night,” said Pat.

She followed the porter to the lift, and Hugo, producing a handkerchief, dabbed it lightly over his forehead.

“Dirty weather, shipmate!” said Hugo. “A very deep depression off the coast of Iceland, laddie.”

He placed a restraining hand on John’s arm as the latter made a movement to follow the snow queen.

“No good, John,” he said gravely. “No good, old man; not the slightest. Don’t waste your time trying to explain tonight. Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned, and not many like a girl who’s just had to give her name and address in a raided night club to a plain-clothes cop who asked her to repeat it twice and then didn’t seem to believe her.”

“But I want to tell her why—”

“Never tell them why. It’s no use. Let us talk of pleasanter things. John, I have brought off the coup of a lifetime. Not that it was my idea. It was Ronnie Fish who suggested it. There’s a fellow with a brain, John. There’s a lad who busts the seams of any hat that isn’t a number eight.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about this amazingly intelligent idea of old Ronnie’s. It’s absolutely necessary that by some means Uncle Lester shall be persuaded to cough up five hundred quid of my capital to enable me to go into a venture second in solidity only to the Mint. The one person who can talk him into it is Ronnie. So Ronnie’s coming to Rudge.”

“Oh?” said John, uninterested.

“And to prevent Uncle Lester making a fuss about this, I’ve invited old man Molloy and daughter to come and visit us as well. That was Ronnie’s big idea. Thos. is rolling in money, and once Uncle Lester learns that, he won’t kick about Ronnie being there. He loves having rich men around. He likes to nuzzle them.”

JOHN was appalled. Limpidly clear though his conscience was, he was able to see that his rather spectacular association with Miss Dolly Molloy had displeased Pat. If she came to stay at Rudge, Pat might think—what might not Pat think?

He became aware that Hugo was speaking to him in a quiet, brotherly voice:

“How did all that come out, John?”

“All what?”

“About Pat. Did she tell you that I paved the way?”

“She did! And look here!”

“All right, old man,” said Hugo, raising a deprecatory hand. “That’s absolutely all right. I don’t want any thanks. You’d have done the same for me. Well, what has happened? Everything pretty satisfactory?”

“Satisfactory!”

“Don’t tell me she turned you down?”

“If you really want to know—yes, she did.”

Hugo sighed.

“I feared as much. There was something about her manner when I was paving the way that I didn’t quite like. Cold. Not responsive. A bit glassy eyed.

“What an amazing thing it is,” Hugo went on, tapping a philosophical vein, “that, in spite of all the ways there are of saying yes, a girl on an occasion like this nearly always says no. An American statistician has estimated that, omitting substitutes like ‘All right,’ ‘You bet,’ ‘O. K.,’ and nasal expressions like ‘uh-huh,’ the English language provides nearly fifty different methods of replying in the affirmative, including yeah, yeth, yum, yo, yaw, chess, chass, chuse, yip, yep, yap, yop, yup, yurp—”

“Stop it!” cried John forcefully.

Hugo patted him affectionately on the shoulder.

“All right, John. All right, old man. I quite understand. You’re upset. A little on edge, yes? Of course you are.

“If I were you, laddie, I would take myself firmly in hand at this juncture. You must see for yourself by now that you’re simply wasting your time fooling about after dear old Pat. A sweet girl, I grant you—one of the best; but if she won’t have you, she won’t, and that’s that. Isn’t it or is it? Take my tip and wash the whole thing out and start looking round for someone else.

“Now, there’s this Miss Molloy, for instance. Pretty. Pots of money. If I were you, while she’s at Rudge, I’d have a decided pop at her. You see, you’re one of those fellows that nature intended for a married man right from the start. You’re a confirmed settler down; the sort of chap that likes to roll the garden lawn and then put on his slippers and light a pipe and sit side by side with the little woman, sharing a twin set of head phones.

“Pull up your socks, John, and have a dash at this Molloy girl. You’d be on velvet with a rich wife.”

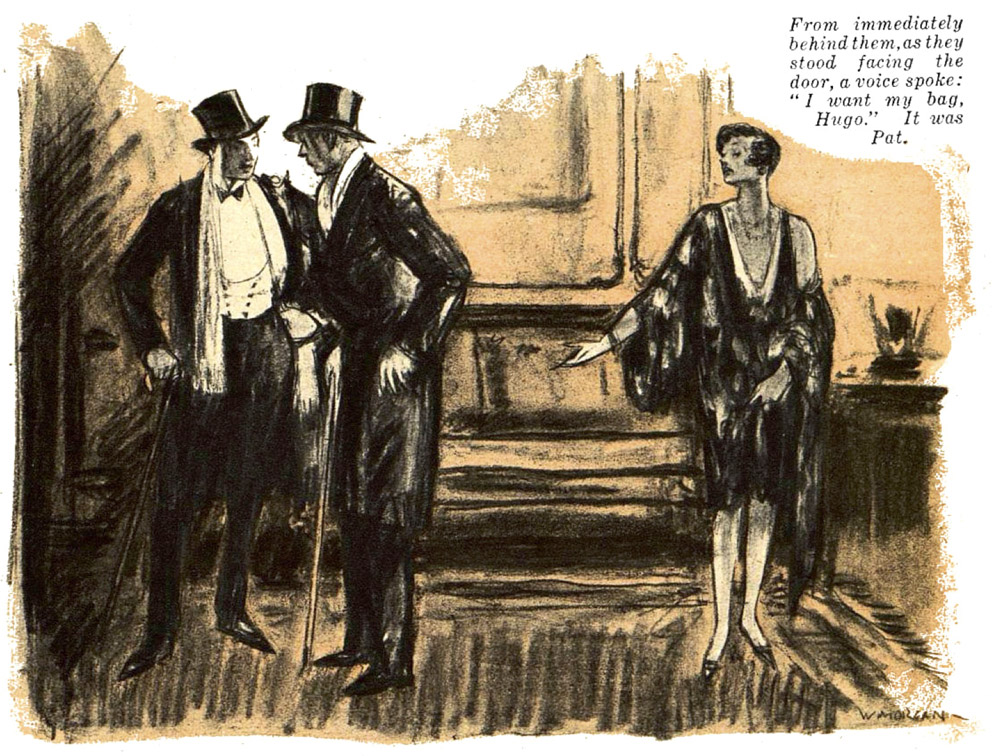

AT several points during this harangue John had endeavored to speak; and he was just about to do so now, when there occurred that which rendered speech impossible. From immediately behind them, as they stood facing the door, a voice spoke:

“I want my bag, Hugo.”

It was Pat. She was standing within a yard of them. Her face was still that of a martyr; but now she seemed to suggest by her expression a martyr whose tormentors have suddenly thought up something new.

“You’ve got my bag,” she said.

“Oh—ah,” said Hugo.

He handed over the beaded trifle, and she took it with a cold aloofness. There was a pause.

“Well, good night,” said Hugo.

“Good night,” said Pat.

“Good night,” said John.

“Good night,” said Pat.

She turned away, and the lift bore her aloft. Its machinery badly needed a drop of oil, and it emitted, as it went, a low, wailing sound that seemed to John like a commentary on the whole situation.

The lift would not have wailed had it had the spirit of prophecy: it would have shaken with laughter. The situation that seemed so black to John develops astonishingly whimsical quirks. Don’t miss next week’s installment.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums