London Magazine, May 1911

AUBREY MICKLEY’S meditations, as he travelled to Wrykyn to begin his career as a member of a public school, would have revealed, if investigated, a certain amount of confusion. A public school was something altogether outside his ken. He had never, though he was within a month of his fifteenth birthday, been even to a private school, his education to date having been entrusted to a series of governesses, merging imperceptibly into a series of tutors. The last but one of the latter series, in conversation with a friend shortly after the expiration of his term of office, had delivered judgment on his late charge in the following words:

“Of all the little beasts, of all the little hounds I ever met, that Mickley kid is the worst. Not that it’s altogether his fault. It’s his fool of a mother. If he’s sent to a public school quick, there’s just a chance that he may get turned into something almost human. But it’s got to be done at once, before she spoils him past repair.”

Which sentiments, by a roundabout route, had reached the ears of Mrs. Mickley’s brother, George; and brother George, who occasionally stayed a week or so with his sister and was a man of observation, came to the conclusion that this exactly summed up his own views on his nephew. The result was an interview, tearful on the part of Mrs Mickley, purple-faced on that of brother George. Mrs. Mickley said George was unjust to Aubrey. George replied that that was only because words could not do justice to him. Mrs. Mickley mentioned that George was forgetting that Aubrey was his only nephew, the only child of his only sister. George said it was precisely because he remembered that that he was taking steps; for he was tired of being the only uncle of a booby, a milksop—George’s vocabulary was a little behind the times—a sneak, a greedy little pig, and a snob. The meeting had then broken up in confusion; but letters had been exchanged, like desultory artillery fire after a battle, and finally the progressive element in the family had carried its point; and Aubrey found himself in the corner of a first-class carriage on his way to Wrykyn and the unknown.

In the main his musings were gloomy. He had not asked to be sent to school. He had sulked for two days when the news was broken to him. He disliked the idea of school. At home you knew where you were. There was an inexhaustible supply of tutors in the world. If you didn’t like one, you complained to your mother, and he was sent back to the shop. Then, in the few days which were bound to elapse before another could be sent on approval, you had a bit of a holiday to yourself. He doubted very much whether this excellent system obtained at a public school.

Then there was the question of food. Rumours had reached him of a certain Spartan element in the public-school cuisine. At home he had always had more than enough of anything he had cared to ask for. A hinted preference for charlotte russe had meant that there would be charlotte russe, not that there might be. He doubted whether at Wrykyn there even might be.

Take it for all in all, this idea of going to school did not appeal to him.

Two things buoyed him up. First, the home authorities had pledged themselves to keep him adequately supplied with hampers—Uncle George, who had put his foot down on the altogether excessive sum which his sister wished to bestow as pocket-money, had been unable to prevent this—and a regular flow of hampers does much to ameliorate the greyest existence. Secondly, Jack Pearse was at Wrykyn, and in West’s house, too, the house at which he himself had been entered.

He hoped for much from Jack Pearse, not on the strength of long acquaintanceship, for they had never met, but owing to the latter’s somewhat unusual relations with his, Aubrey’s, Uncle George.

There is no doubt that, on several counts, Aubrey’s Uncle George deserves our sympathy, consideration and respect. In the first place, he disliked and despised Aubrey. That in itself prejudices one in his favour. In the second place, he had exploited Jack Pearse.

Without his help, Jack would probably have followed in his father’s footsteps and become a gamekeeper on Uncle George’s estate in Shropshire. There is nothing vivid and revolutionary in the conditions of life in those parts, and the odds on a Shropshire gamekeeper’s son becoming in the fulness of time a Shropshire gamekeeper are large. The world is far away, and the noise of it seldom reaches the quiet meadows by the banks of the Severn, unsettling the minds of budding gamekeepers and turning their thoughts to larger things. But for the fact that by a mere accident Uncle George had been struck by Jack’s infantile intelligence and had decided to develop it, Jack might never have got further south than Wolverhampton. As it was, he had reached Wrykyn, and was flourishing there with great success. He was now seventeen, high up in the Engineering Sixth, a useful bowler and one of the best and most energetic forwards the school had had for half-a-dozen seasons.

It was on this man of mettle that Aubrey was relying to introduce him to Wrykyn as he should be introduced. To others he might be unknown, but Jack Pearse would reverence him. By degrees, as the train raced on towards his destination, Jack Pearse had taken on in his eyes an attitude of humble devotion which would have been almost excessive in an old family retainer in melodrama.

* * * * *

Meanwhile, at West’s, the object of his meditations was also thinking of him, though hardly as humbly or devotionally as he should have done. Jack Pearse, who had received instructions from Uncle George before leaving, had taken an early train to school in order to see Fry, the head of West’s, as soon as possible. He was now having tea with him in his study. Fry was a large, stout, placid individual, with a broad, good-natured face. Everybody liked him, but his best friend would not have denied that he was quite incompetent to be head of a house. Fortunately for the peace of mind of Mr. West, his post was practically a sinecure, for the house had never been in a better state. Houses pass through phases, and West’s, six years ago one of the worst in the school, was running along now on oiled wheels.

“There’s a kid called Mickley coming here this term,” said Pearse. “I know his uncle. Do you mind if he fags for me?”

“I don’t mind anything,” said Fry placidly and with truth. “What sort of a kid is he?”

“I’ve never met him,” said Pearse guardedly. Uncle George had spoken his mind with freedom on the subject of Aubrey, but it would be rough luck to prejudice Fry against him from the start. “His uncle’s an awfully good sort. The best sort I’ve ever met. An absolute ripper!”

“Pity it isn’t the uncle instead of the kid that’s coming here. By the way, did you know that Stanworth was coming to West’s this term? He’s up in Baxter’s old study now. Shall I ask him down here?”

“Stanworth! Great Scott, that blighter!”

“Oh, I don’t mind Stanworth,” said Fry comfortably. “He’s not a bad sort.”

“I can’t stand the man.”

“He’ll be a lot of help at cricket,” argued Fry.

This was true. Whatever his other defects, there was no doubt that next term Stanworth would be the best bat in the school. He was one of those tall, languid youths who seem to take to batting naturally. Batting was his one form of athletic expression. He did not play football, and even on the cricket-field rarely ran except between the wickets. He was one of Nature’s points, born to stand in an attitude of limp grace and watch cover or third-man sprinting in pursuit of an agile ball. As to his other qualities, he was old for his years, brilliantly clever at Classics, and what theatrical advertisements call a “good dresser.” In addition to being in the first eleven, he was a school prefect.

“He’s an amusing chap, Stanworth,” continued Fry. “He was making me laugh just now about a Frenchman he saw at the Casino at Nice. His people have taken a villa at Nice for a bit; that’s why he’s coming here. This Frenchman chap was gambling at the tables, and thought he had put five francs on something, whereas really it was on something else, or something like that. I can’t quite remember how it went. Anyhow, I know he thought he’d won when he’d really lost. But you get him to tell it you. You’ll laugh.”

“I’ll save it up for a rainy day,” said Pearse, without enthusiasm. “It sounds screamingly funny. I can’t make out what you see in the man. He makes me sick.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Fry.

II.

Aubrey’s first impressions of Wrykyn need not be recounted, especially as, at the end of the first quarter of an hour, they were one and all engulfed, swamped, avalanched and tidal-waved by the cataclysmal information that he would have to fag—and fag, at that, for Jack Pearse. Just as a man might feel who, arrayed in his best, and walking rapidly along Piccadilly on his way to lunch with a duke, should cannon into a lamppost, so did Aubrey feel at the first shock of the news.

Pearse found him in the matron’s room, being treated with a certain motherly familiarity, perhaps, but still quite tolerably respectfully, and slapped the information into him like a charge of round-shot.

“Are you Mickley?” he said. “My name’s Pearse. I know your uncle.” (“Know your uncle!” Great feudal system!) “You’ll be fagging for me this term.”

“Fagging?” said Aubrey. The word conveyed nothing to him.

And it was at this point, when Pearse began to explain the precise nature and meaning of the word “fagging,” that the avalanche-cum-tidal-wave started on its course.

To Pearse his dumb stupefaction seemed merely the decent shyness of a new boy, strange to his surroundings. He approved of it. It seemed to him that Uncle George must have been wrong in his diagnosis. This kid was not the terror his uncle had imagined him.

“It’s all right,” he said. “It isn’t anything to spoil your sleep. And, anyhow, you haven’t got to start at once. You don’t have to fag here your first week. Whose dormitory are you in?”

“Stanworth’s,” said the matron, replying, vice Aubrey, incapacitated. “The one that was Baxter’s, last term. He will be a house prefect, of course, being a school prefect.”

“Isn’t there any room in mine?” asked Pearse.

Aubrey found speech.

“I prefer Stanworth’s,” he said haughtily. He did not know what exactly Stanworth’s might be, but it was imperative that this person be put in his place.

* * * * *

On the whole, Aubrey did not find his first week at Wrykyn unpleasant. It was a Wrykyn tradition that things should be made as easy as possible for a new boy until he might be expected to have grown accustomed to the place; and in West’s house in particular there was very little to grumble at. The food suffered by comparison with his mother’s generous menus, but it was eatable, there was plenty of it, and the school shop was very handy. Work was a nuisance, but apparently inevitable, and he resigned himself to it.

He liked being in Stanworth’s dormitory. Stanworth struck him as an excellent sort of fellow. He was the only member of the house who seemed really to enjoy listening to his, Aubrey’s, conversation. Twice in the first week Aubrey took tea with him in his study. His view of the matter was that he and Stanworth were kindred souls. Stanworth’s, as confided to his friend Benger, a day-boy, differed slightly from this.

“West’s is a pretty slow sort of hole,” he said, “but at any rate I’ve found one genuine freak in it. Do you know a new kid named Mickley, a little fat brute who looks as if he was bursting out of his clothes? This is apparently the first time he’s been to any sort of school, and his views on things in general are worth hearing. I can sit and listen to him by the hour.”

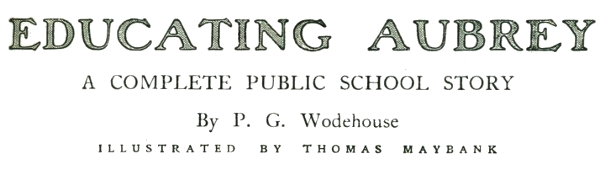

Life only began to show

itself as not all joy, jollity and song when the first week came to an end and

his period of servitude commenced. In the rush of events he had almost

forgotten what was hanging over him, and the shock when young Gooch, who fagged

for Fry, came to him, as he was chatting with Stanworth in his study, with the

information that Pearse was waiting for him to get his tea ready, was almost as

great as that which he had received on his first evening when the nature of

fagging had been explained to him in the matron’s room.

Life only began to show

itself as not all joy, jollity and song when the first week came to an end and

his period of servitude commenced. In the rush of events he had almost

forgotten what was hanging over him, and the shock when young Gooch, who fagged

for Fry, came to him, as he was chatting with Stanworth in his study, with the

information that Pearse was waiting for him to get his tea ready, was almost as

great as that which he had received on his first evening when the nature of

fagging had been explained to him in the matron’s room.

He looked helplessly at Stanworth.

“Don’t you want to?” said Stanworth. “You’d better write him a note. Put it nicely. Say that you have a previous engagement, and add that you will be delighted if he will drop in and join us here.”

It struck Aubrey as an excellent idea, all but the last part.

“But I don’t want him here,” he said.

“No? Well, just say you’ve got a previous engagement.”

Jack Pearse’s feelings, when Aubrey’s civil but rather distant note was brought to him, were mixed. The bearer was Hopwood, Stanworth’s fag and, making his deductions from this fact, he suspected the hand of Stanworth in the matter. Even Aubrey would not have been such a fool, after a week’s experience of school and its ways, as to write the note, unless he had gathered, from someone who might be supposed to know, that it would be all right. He was furious with Stanworth. He did not suppose that his fellow prefect had deliberately urged Aubrey to serious revolt. He imagined, correctly, that he had done it merely to amuse himself, and he objected strongly to Stanworth amusing himself at his expense. If any of the other house prefects had done it, he would have laughed; but he disliked Stanworth, and a joke is the last thing one wants to share with a person one dislikes.

His distaste for Stanworth had grown with closer acquaintance. As a day-boy, the other had come but seldom into immediate contact with him; but fellow house prefects cross one another’s paths frequently. He would have found it difficult to say exactly why he objected to Stanworth. To himself he put it vaguely that the other’s “side” annoyed him. But he knew that it was more than that. What was really the trouble, though he could not analyse it, was that Stanworth was an individual in a community, an alien, an unassimilated unit. In other words, though he wore a West’s tie, he was at heart still a day-boy. He did not belong to West’s. Jack, who had been a member of the house for nearly five years, was filled with the house spirit. West’s mattered a great deal to him. It did not matter in the least to Stanworth.

He thought the thing over as he prepared tea for himself. He must keep his head. To lose his temper would constitute an unmistakable score to Stanworth.

Having finished tea, and judging that his fag-to-be had probably finished his, he went upstairs to the other study. Aubrey was still there. He looked replete and contented.

“Hallo, Pearse,” said Stanworth. “Pity you didn’t come earlier. We’ve finished.”

“I’ve had tea, thanks,” said Pearse. “Come along to my study, Mickley, for a minute, will you?”

Aubrey looked at Stanworth for guidance, but Stanworth merely beamed.

“Sorry you have to be going, Mickley,” he said. “Look in any time you like.”

“What do you want?” said Aubrey, when he and Jack Pearse were outside.

“Just a chat,” said Pearse. “I’m seeing nothing of you.”

He led the way to the study. The remains of his solitary tea were on the table.

“You might just wash those up first,” he said. “There’s a tin basin over in the corner. You can fill it in the bathroom. Buck along!”

Aubrey hesitated. He was on the point of refusing, but the absence of Stanworth robbed him of the necessary courage.

He compromised.

“I don’t see why I’ve got to,” he said.

“Got to!” said Pearse. “Don’t say that. It ought to be a pleasure. Charge along. You know where the bathroom is.”

Aubrey felt out of his

depth. It was all wrong that he should be compelled to do menial work like this

for a social inferior, but it didn’t seem possible to get out of it. Jack

Pearse was quite quiet and pleasant, but there was something in his manner that

suggested possibilities. He picked up the basin and went out.

Aubrey felt out of his

depth. It was all wrong that he should be compelled to do menial work like this

for a social inferior, but it didn’t seem possible to get out of it. Jack

Pearse was quite quiet and pleasant, but there was something in his manner that

suggested possibilities. He picked up the basin and went out.

“You mustn’t let Stanworth rot you,” said Pearse, as the water splashed over the plates.

The idea that Stanworth could treat him with anything but sympathetic respect offended Aubrey. He grunted.

“You must look out for that,” continued Jack. “Fellows will, if you give them a chance. A safe rule for you is to do just what I tell you. If I tell you do a thing and somebody else tells you not to, you go ahead and do it, and refer him to me.”

“I don’t see why—”

“You don’t have to. Yours is not to reason why, yours but to do—or die.”

He picked up a swagger-stick, toyed with it for a moment, and laid it down. A thrill of dismay shot through Aubrey. He had not realised this factor in the situation. He addressed himself to his work with a thoughtful energy.

“Finished?” said Pearse. “That’s right. You can pop off now. I shall want tea tomorrow after school—for two. Fry’s coming. Don’t forget.”

III.

By the end of the third week of term Jack Pearse was feeling discouraged. Things were going against him. That Aubrey now looked on fagging as another of the unavoidable evils of public-school life, and went through with it without further attempt at resistance, mattered little, for in every other respect he was unchanged; and the problem of how his improvement was to be effected worried Pearse.

If it had not been for Uncle George, he would have dismissed it from his mind, for there was nothing in the least attractive in the prospect of being a combination of nurse and policeman to a small boy. But he knew that Uncle George felt very strongly on the subject of Aubrey, and the older he grew and the more clearly he saw the possibilities which his backer had opened to him by sending him to Wrykyn, the deeper became his sense of obligation. The only possible way in which he could repay him at present was by reforming Aubrey; and he certainly had not made much progress in that direction.

There seemed so little that he could do. He had so small a control over his charge’s movements. If Aubrey, when not fagging, had spent his time, like other juniors, in the junior dayroom, his mind would have been easy. The atmosphere of a junior dayroom in a public school is essentially bracing, and characters like Aubrey’s seldom fail to derive benefit from it. But Aubrey avoided the junior dayroom. As far as Pearse could see, he appeared to have the free run of Stanworth’s study. At any rate, he was nearly always to be found there of an afternoon.

It irritated Jack, this incessant intrusion of Stanworth into his affairs. He objected to him. Stanworth refused to be assimilated into the house. His friends were all day-boys. He held day-boy tea-parties nearly every afternoon. To Pearse, with his boarder outlook on life, he seemed to cheapen the house. Your genuine boarder resents strangers in his house almost as keenly as the Constantinople dog used to resent strange dogs in his street. It was maddening to meet grinning day-boys wandering about the house as if they had bought it. He had no objection to day-boys in their proper place, but that place was not the interior of West’s. And Stanworth’s friends were such wasters, too, the louts!

Nevertheless, it was a

bad move to assail Aubrey on the subject. He regretted it directly he had done

it; but he was feeling particularly irritated that afternoon. To begin with, a

degraded weed in a day-boy’s cap had charged into his study while he was

changing after football and, having grinned all across his beastly face, had

retired with the statement that he had “thought this was Stanworth’s.” That had

upset him. And when, on the top of it, Aubrey had given, as an excuse for being

late, that he had been up in Stanworth’s study, where the clock was wrong, he

spoke his mind.

Nevertheless, it was a

bad move to assail Aubrey on the subject. He regretted it directly he had done

it; but he was feeling particularly irritated that afternoon. To begin with, a

degraded weed in a day-boy’s cap had charged into his study while he was

changing after football and, having grinned all across his beastly face, had

retired with the statement that he had “thought this was Stanworth’s.” That had

upset him. And when, on the top of it, Aubrey had given, as an excuse for being

late, that he had been up in Stanworth’s study, where the clock was wrong, he

spoke his mind.

“Why the dickens are you always up there?” he growled. “Why can’t you stay in the junior dayroom like other kids?”

And more to the same effect.

Aubrey listened in silence, and duly handed it all on to Stanworth.

Stanworth was not likely to miss such a chance. It was, as the Americans say, pie to him. On the following afternoon he knocked at Pearse’s door. “Oh, please, Pearse,” he said timidly, “may Mickley come to my study this evening?”

Pearse glared.

“Would you mind very much? I thought I’d better come and ask you.”

“In other words,” said Jack, hot about the ears, “I suppose you mean that I’d better mind my own business?”

“I shouldn’t have put it in that way,” said Stanworth smoothly. “But still, as you have suggested it——”

“Oh, all right,” said Jack. “I know it’s a score to you; you needn’t go on. But if you can’t see what rotten bad form it is for a prefect always having a kid fooling about in his study——”

“What’s the objection? This kid’s a freak. He amuses me!”

“The objection is,” snapped Jack, “that he’s already got side enough for ten, and if you encourage him he will probably in time get almost as bad as you. Goodbye! Run along to your beastly day-boys.”

Which outburst, however satisfying to the feelings, did not, as he saw perfectly clearly, advance him in the slightest degree towards the accomplishment of his object. With the difference that he and Stanworth, instead of exchanging an occasional word when they met, now maintained a frigid silence, the situation was unaltered.

* * * * *

It was the easy-going Fry who first revealed to him an unsuspected joint in Stanworth’s armour. Fry, plainly with something on his mind, settled himself in one of Pearse’s deck-chairs one evening when West’s, with the exception of the prefects, were over at the Great Hall, doing prep., and talked jerkily for a while of house football prospects.

“I say,” he said at last, “what ought I to do, do you think, in a case like this?”

“Like what?”

“Well, it’s this way. I was up in Stanworth’s study just now, and he’s got one of those what-d’you-call-it things. You know.”

Lucid as this statement was, Pearse asked for further particulars.

“One of those gambling things,” said Fry. “A sort of board with holes and numbers, and you roll a ball.”

“Roulette?”

“No; it’s not roulette. It’s a different sort of game. Stanworth got it at Nice. It’s a sort of small model of the game they play at the Casino there. You roll an indiarubber ball, and it falls into one of the holes.”

“Well?”

“Well, I mean, what ought I to do? Of course, he’s got no right to have a thing like that in the house. West would be frightfully sick. There’d be an awful row.”

“Does he use it?”

“That’s what I can’t make out. You know what Stanworth is. He puts you off. I asked him that, and he said that nobody in the house except me had ever seen it. That sounds all right, don’t you think?”

“Probably he plays with that day-boy crew he’s always having in. I don’t see that you can do anything.”

“I don’t either. It isn’t as if he played with chaps in the house.”

“If he does, you can jump on him.”

Fry looked doubtful.

“I don’t know—even then. You see, he’s a school prefect, and all that. It’s beastly awkward. Still, I suppose it’ll be all right.”

He wandered out of the study; and Pearse, who was in the middle of a Latin Prose, dismissed the thing from his mind. He disliked thinking of Stanworth.

He had completely forgotten the conversation, when, about a week later, having a note to send across to the School House, and having failed to find Aubrey in the junior dayroom, he went in search of him to Stanworth’s study. He was rather pleased at having a legitimate excuse for routing him out from that secure retreat.

He was wearing carpet slippers, and his feet made no noise. He knocked sharply, and went in.

He had never been inside this study since it had become Stanworth’s, and he was surprised at the luxury of it. He had always known that Stanworth had a good deal of money, but he was not prepared for the display of wealth that met his eye.

He did not look at the ornaments long, however. He found the occupants of the room more interesting. There were four of them—Stanworth himself, two day-boys (whom he only knew by sight), and Aubrey. They were gathered round a small table in the middle of the room, and on the table was a curious apparatus that puzzled him for a moment, and then sent his mind back like a flash to his conversation with Fry. It consisted of a polished, cuplike piece of wood, in the bottom of which was a circle of holes, each with a number opposite it, and a strip of green baize, divided into numbered sections. There was money lying about this green baize, a half-crown, a shilling, and some coppers. A small red ball was bumping slowly round the circle of holes.

His entry effectually diverted attention from the game. All four players faced sharply round.

Stanworth was the first to recover himself.

“And what can we do for our Mr. Pearse?” he said.

“What’s all this?” demanded Pearse.

Stanworth smiled, the supercilious smile that was the cause of a good deal of his unpopularity.

“Do you remember a little talk we had the other day on the subject of minding one’s own business?” he said.

“This is my business!”

“How do you make that out?”

“Because you’ve lugged this kid Mickley into it. I promised his people that I’d keep an eye on him in this place, and I’m not going to have him rooked by the first bounder that’s cad enough to take his money off him!”

Stanworth rolled the ball gently to and fro with his forefinger.

“And what do you propose to do about it?” he said.

The question brought Jack up with a jerk. What did he propose to do about it? It suddenly occurred to him that he did not know.

“Going to tell West?”

No; he was not going to tell West. Etiquette is rigid at school, and a house prefect has to have a contempt for it before he reports a matter to the housemaster on his own account. Etiquette demanded that he should consider his part done when he had told Fry. And he could see Fry handling the situation. There would be an unofficial protest to Stanworth, a lazy “I-say-old-chap-you-know,” and Fry would doze off again, thankful that the business was over. To Pearse, in his militant state of mind, this did not seem the ideal method.

“Or are you going to give me a good, hard knock?”

Jack’s eyes gleamed joyfully. An idea had come to him.

“The first thing I’m going to do is to ask your two moth-eaten friends to toddle!” he said. “This is purely a house affair. We don’t want outsiders mixed up in it.”

He looked from one day-boy to the other and back again, and opened the door. For a moment they hesitated, but not longer. The fact presented itself to their minds that while Stanworth was a school prefect, and, as such, sacrosanct, and not to be smitten by inferiors, they were nothing of the kind. They had no intention of brawling with Pearse. As he had very sensibly put it, it was a house affair. They were not needed. They would withdraw.

They withdrew.

Jack closed the door gently behind them.

“Now!” he said.

There was a serviceable walking-stick in the corner, one of those sticks with a heavy knob for a handle. He picked it up, and gave it a half-swing. His eye moved about the room till it rested on a bulbous china vase. He raised the stick, and brought it down with a crash.

Stanworth sprang forward, with a howl of wrath and dismay.

“Get back!” said Jack. “You’re in the way!”

“What the deuce do you think you’re playing at?”

Jack raised the stick again.

“Indoor hockey,” he said. “Society’s latest craze. Some people,” he continued thoughtfully, “think it’s bad luck to break a looking-glass. I wonder!”

There was a second

crash, louder than the first.

There was a second

crash, louder than the first.

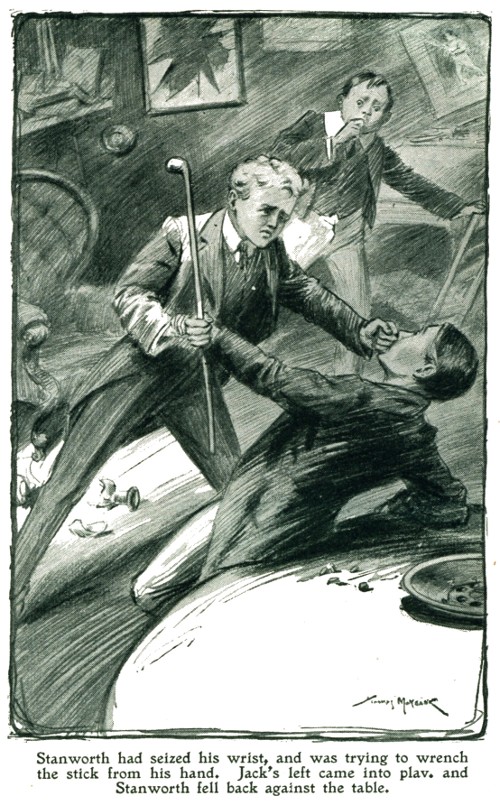

Stanworth had seized his wrist, and was trying to wrench the stick from his hand. Jack’s left came into play, and Stanworth fell back against the table.

Jack looked at him reproachfully.

“I told you you were in the way,” he said, smashing a photograph-glass.

“I’m a school-prefect!” cried Stanworth. “I’ll have you up before a prefects’ meeting!”

“Do!” Another vase burst into a shower of china. “And tell ’em all the facts. It’ll keep them merry and bright. The Easter term’s always pretty dull.”

Two minutes later Jack looked round him with satisfaction.

“That’ll do for the present,” he said. “Thanks for the loan of the stick. Mickley, come down to my study. I want a short talk with you. No; better take this note over to the School House first. There’s no answer. Come to my study when you get back.”

The distance between West’s and the School House was not large, but Aubrey managed to put in a good deal of hard thinking while covering it. There had been a remarkable upheaval in his mind. Primitive things had been happening, and he was readjusting his views. A sudden humility competed for first place among his emotions, with an equally sudden respect for Jack Pearse. For the first time he realised that he was in a world where antecedents, however aristocratic, are as nothing beside present performances; where muscles were more than coronets, and a simple swagger-stick than Norman blood.

He entered Jack’s study, walking mincingly, like Agag.

“Come in!” said Jack. “Now, then, what about it? This is where you make your big decision, my blue-eyed boy. We have here a handy swagger-stick. Shall it be ten of the premier quality with this, or will you listen to a small scheme I have mapped out? This is the scheme: that you stop behaving like a young blighter, and settle down to be a credit to the house and yourself. You’d be a pretty decent weight even without the fat, and there’s no reason, if you work hard, why you shouldn’t play in the house second scrum in the house matches at the end of the term. It’ll mean sweating. You’ll have to learn the game, and you’ll have to train. Well, which is it to be?”

He switched the swagger-stick meditatively in the air.

“I believe they shove whalebone, or something, in these things,” he said pensively. “Awfully supple they are!”

* * * * *

Towards the middle of March—Uncle George had forbidden her to do it earlier—Mrs. Mickley paid her first visit to the school, and bore Aubrey off to tea in the town.

“My poor darling,” she said sympathetically, “you look positively starved! Never mind, the holidays will soon be here. Now, shall we begin with muffins, my pet? And then you would like some of those nice cream cakes in the win——”

A look slightly wistful, but in the main of horror and repulsion, spread itself over Aubrey’s face.

“I think I’d like some of those oatmeal biscuits,” he said austerely.

“Oatmeal biscuits!”

“Or a rusk or two. I’m in training. I’m playing for the house second against Seymour’s on Saturday. And Jack Pearse says if we buck up like we did against Day’s last week, we shall simply knock the stuffing out of them!”

P. G. Wodehouse.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums