The New Magazine, December 1926

HE roof of the Sheridan Apartment House, near Washington Square, New York. Let us examine it. There will be stirring happenings on this roof in due season and it is as well to know the ground.

HE roof of the Sheridan Apartment House, near Washington Square, New York. Let us examine it. There will be stirring happenings on this roof in due season and it is as well to know the ground.

The Sheridan stands in the heart of New York’s Bohemian and artistic quarter. If you threw a brick from any of its windows you would be certain to brain some rising young interior decorator, some Vorticist sculptor or a writer of revolutionary vers libre. And a very good thing, too. Its roof, cosy, compact and ten storeys above the street, is flat, paved with tiles and surrounded by a low wall, jutting up at one end of which is an iron structure—the fire-escape. Climbing down this, should the emergency occur, you would find yourself in the open-air premises of the Purple Chicken restaurant—one of those numerous oases in this great city where, in spite of the law of Prohibition, you can still, so the cognoscenti whisper, “always get it if they know you.” A useful thing to remember.

On the other side of the roof, opposite the fire-escape, stands what is technically known as a “small bachelor apartment, penthouse style.” It is a white-walled, red-tiled bungalow and the small bachelor who owns it is a very estimable young man named George Finch, originally from East Gilead, Idaho, but now, owing to a substantial legacy from an uncle, a unit of New York’s Latin Quarter. For George, no longer being obliged to earn a living, has given his suppressed desires play by coming to the metropolis and trying his hand at painting. From boyhood up he had always wanted to be an artist; and now he is an artist; and what is more, probably the worst artist who ever put brush to canvas.

For the rest, that large round thing that looks like a captive balloon is the water-tank. That small oblong thing that looks like a summerhouse is George Finch’s outdoor sleeping-porch. Those things that look like potted shrubs are potted shrubs. That stoutish man sweeping with a broom is George’s valet, cook and man-of-all-work, Mullett.

And this imposing figure with the square chin and the horn-rimmed spectacles which, as he comes out from the door leading to the stairs, flash like jewels in the sun, is no less a person than J. Hamilton Beamish, author of the famous Beamish Booklets (“Read Them and Make the World Your Oyster”) which have done so much to teach the populace of the United States observation, perception, judgment, initiative, will-power, decision, business acumen, resourcefulness, organisation, directive ability, self-confidence, driving-power, originality—and, in fact, practically everything else from Poultry-Farming to Poetry.

The first emotion which any student of the Booklets would have felt on seeing his mentor in the flesh—apart from that natural awe which falls upon us when we behold the great—would probably have been surprise at finding him so young. Hamilton Beamish was still in the early thirties. But the brain of Genius ripens quickly; and those who had the privilege of acquaintance with Mr. Beamish at the beginning of his career say that he knew everything there was to be known—or behaved as if he did—at the age of ten.

Hamilton Beamish’s first act on reaching the roof of the Sheridan was to draw several deep breaths—through the nose, of course. Then, adjusting his glasses, he cast a flashing glance at Mullett and, having inspected him for a moment, pursed his lips and shook his head.

“All wrong!” he said.

The words, delivered at a distance of two feet in the man’s immediate rear, were spoken in the sharp, resonant voice of one who Gets Things Done—which, in its essentials, is rather like the note of a seal barking for fish. The result was that Mullett, who was highly strung, sprang some eighteen inches into the air and swallowed his chewing-gum. Owing to that great thinker’s practice of wearing No-Jar Rubber Soles (“They Save the Spine”), he had had no warning of Mr. Beamish’s approach.

“All wrong!” repeated Mr. Beamish.

And when Hamilton Beamish said “All wrong!” it meant “All wrong!” He was a man who thought clearly and judged boldly, without hedging or vacillation. He called a Ford a Ford.

“Wrong, sir?” faltered Mullett, when, realising that there had been no bomb-outrage after all, he was able to speak.

“Wrong. Inefficient. Too much waste motion. From the muscular exertion which you are using on that broom you are obtaining a bare sixty-three or sixty-four per cent. of result-value. Correct this. Adjust your methods. Have you seen a policeman about here?”

“A policeman, sir?”

Hamilton Beamish clicked his tongue in annoyance. It was waste motion, but even efficiency experts have their feelings.

“A policeman. I said a policeman and I meant a policeman.”

“Were you expecting one, sir?”

“I was and am.”

Mullett cleared his throat.

“Would he be wanting anything, sir?” he asked a little nervously.

“He wants to become a poet. And I am going to make him one.”

“A poet, sir?”

“Why not? I could make a poet out of far less promising material. I could make a poet out of two sticks and a piece of orange-peel if they studied my booklet carefully. This fellow wrote to me, explaining his circumstances and expressing a wish to develop his higher self and I became interested in his case and am giving him special tuition. He is coming up here to-day to look at the view and write a description of it in his own words. This I shall correct and criticise. A simple exercise in elementary composition.”

“I see, sir.”

“He is ten minutes late. I trust he has some satisfactory explanation. Meanwhile, where is Mr. Finch? I would like to speak to him.”

“Mr. Finch is out, sir.”

“He always seems to be out nowadays. When do you expect him back?”

“I don’t know, sir. It all depends on the young lady.”

“Mr. Finch has gone out with a young lady?”

“No, sir. Just gone to look at one.”

“To look at one?” The author of the Booklets clicked his tongue once more. “You are drivelling, Mullett. Never drivel—it is dissipation of energy.”

“It’s quite true, Mr. Beamish. He has never spoken to this young lady—only looked at her.”

“Explain yourself.”

“Well, sir, it’s like this. I’d noticed for some time past that Mr. Finch had been getting what you might call choosey about his clothes . . .”

“What do you mean, choosey?”

“Particular, sir.”

“Then say particular, Mullett. Avoid jargon. Strive for the Word Beautiful. Read my booklet on Pure English. Well?”

“Particular about his clothes, sir, I noticed Mr. Finch had been getting. Twice he had started out in the blue with the invisible pink twill and then suddenly stopped at the door of the elevator and gone back and changed into the dove-grey. And his ties, Mr. Beamish! There was no satisfying him. So I said to myself, ‘Hot dog!’ ”

“You said what?”

“Hot dog, Mr. Beamish.”

“And why did you use this revolting expression?”

“What I meant was, sir, that I reckoned I knew what was at the bottom of all this.”

“And were you right in this reckoning?”

A coy look came into Mullett’s face.

“Yes, sir. You see, Mr. Finch’s behaviour having aroused my curiosity, I took the liberty of following him one afternoon. I followed him to Seventy-Ninth Street, East, Mr. Beamish.”

“And then?”

“He walked up and down outside one of those big houses there and presently a young lady came out. Mr. Finch looked at her and she passed by. Then Mr. Finch looked after her and sighed and came away. The next afternoon I again took the liberty of following him and the same thing happened. Only this time the young lady was coming in from a ride in the Park. Mr. Finch looked at her and she passed into the house. Mr. Finch then remained staring at the house for so long that I was obliged to go and leave him at it, having the dinner to prepare. And what I meant, sir, when I said that the duration of Mr. Finch’s absence depended on the young lady was that he stops longer when she comes in than when she goes out. He might be back at any minute, or he might not be back till dinnertime.”

Hamilton Beamish frowned thoughtfully.

“I don’t like this, Mullett.”

“No, sir?”

“It sounds like love at first sight.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Have you read my booklet on the Marriage Sane?”

“Well, sir, what with one thing and another and being very busy about the house . . .”

“In that booklet I argue very strongly against love at first sight.”

“Do you indeed, sir?”

“I expose it for the mere delirious folly it is. The mating of the sexes should be a reasoned process, ruled by the intellect. What sort of a young lady is this young lady?”

“Very attractive, sir.”

“Tall? Short? Large? Small?”

“Small, sir. Small and roly-poly.”

Hamilton Beamish shuddered violently.

“Don’t use that nauseating adjective! Are you trying to convey the idea that she is short and stout?”

“Oh, no, sir, not stout. Just nice and plump. What I should describe as cuddly.”

“Mullett,” said Hamilton Beamish, “you will not, in my presence and while I have my strength, describe any of God’s creatures as cuddly. Where you picked it up I cannot say, but you have the most abhorrent vocabulary I have ever encountered . . . What’s the matter?”

The valet was looking past him with an expression of deep concern.

“Why are you making faces, Mullett?” Hamilton Beamish turned. “Ah, Garroway,” he said, “there you are at last. You should have been here ten minutes ago.”

A policeman had come out on to the roof.

II

The policeman touched his cap. He was a long, stringy policeman, who flowed out of his uniform at odd spots, as if Nature, setting out to make a constable, had had a good deal of material left over which it had not liked to throw away but hardly seemed able to fit neatly into the general scheme. He had large, knobby wrists of a geranium hue and just that extra four or five inches of neck which disqualify a man for high honours in a beauty competition. His eyes were mild and blue and from certain angles he seemed all Adam’s apple.

“I must apologise for being late, Mr. Beamish,” he said. “I was detained at the station-house.” He looked at Mullett uncertainly. “I think I have met this gentleman before?”

“No, you haven’t,” said Mullett quickly.

“Your face seems very familiar.”

“Never seen me in your life.”

“Come this way, Garroway,” said Hamilton Beamish, interrupting curtly. “We cannot waste time in idle chatter.” He led the officer to the edge of the roof and swept his hand round in a broad gesture. “Now, tell me. What do you see?”

The policeman’s eye sought the depths.

“That’s the Purple Chicken down there,” he said. “One of these days that joint will get pinched.”

“Garroway!”

“Sir?”

“For some little time I have been endeavouring to instruct you in the principles of pure English. My efforts seem to have been wasted.”

The policeman blushed.

“I beg your pardon, Mr. Beamish. One keeps slipping into it. It’s the effect of mixing with the boys—with my colleagues—at the station-house. They are very lax in their speech. What I meant was that in the near future there was likely to be a raid conducted on the premises of the Purple Chicken, sir. It has been drawn to our attention that the Purple Chicken, defying the Eighteenth Amendment, still purveys alcoholic liquors.”

“Never mind the Purple Chicken. I brought you up here to see what you could do in the way of a word-picture of the view. The first thing a poet needs is to develop his powers of observation. How does it strike you?”

The policeman gazed mildly at the horizon. His eye flitted from the roof-tops of the city, spreading away in the distance, to the waters of the Hudson, glittering in the sun. He shifted his Adam’s apple up and down two or three times, as one in deep thought.

“It looks very pretty, sir,” he said at length.

“Pretty?” Hamilton Beamish’s eyes flashed. You would never have thought, to look at him, that the J. in his name stood for James and that there had once been people who had called him Jimmy. “It isn’t pretty at all.”

“No, sir.”

“It’s stark.”

“Stark, sir?”

“Stark and grim. It makes your heart ache. You think of all the sorrow and sordid gloom which those roofs conceal and your heart bleeds. I may as well tell you, here and now, that if you are going about the place thinking things pretty you will never make a modern poet. Be poignant, man, be poignant!”

“Yes, sir. I will, indeed, sir.”

“Well, take your notebook and jot down a description of what you see. I must go down to my apartment and attend to one or two things. Look me up to-morrow.”

“Yes, sir. Excuse me, sir, but who is that gentleman over there, sweeping with the broom? His face seemed so very familiar.”

“His name is Mullett. He works for my friend, George Finch. But never mind about Mullett. Stick to your work. Concentrate! Concentrate!”

“Yes, sir. Most certainly, Mr. Beamish.”

He looked with dog-like devotion at the thinker; then, licking the point of his pencil, bent himself to his task.

Hamilton Beamish turned on his No-Jar rubber heel and passed through the door to the stairs.

III

Following his departure, silence reigned for some minutes on the roof of the Sheridan. Mullett resumed his sweeping and Officer Garroway scribbled industriously in his notebook. But after about a quarter of an hour, feeling apparently that he had observed all there was to observe, he put book and pencil away in the recesses of his uniform and, approaching Mullett, subjected him to a mild but penetrating scrutiny.

“I feel convinced, Mr. Mullett,” he said, “that I have seen your face before.”

“And I say you haven’t,” said the valet testily.

“Perhaps you have a brother, Mr. Mullett, who resembles you?”

“Dozens. And even mother couldn’t tell us apart.”

The policeman sighed.

“I am an orphan,” he said, “without brothers or sisters.”

“Too bad.”

“Stark,” agreed the policeman. “Very stark and poignant. You don’t think I could have seen a photograph of you anywhere, Mr. Mullett?”

“Haven’t been taken for years.”

“Strange!” said Officer Garroway, meditatively. “Somehow—I cannot tell why—I seem to associate your face with a photograph.”

“Not your busy day, this, is it?” said Mullett.

“I am off duty at the moment. I seem to see a photograph—several photographs—in some sort of collection . . .”

There could be no doubt by now that Mullett had begun to find the conversation difficult. He looked like a man who has a favourite aunt in Poughkeepsie and is worried about her asthma. He was turning to go when there came out on to the roof from the door leading to the stairs a young man in a suit of dove-grey.

“Mullett!” he called.

The other hurried gratefully towards him, leaving the officer staring pensively at his spacious feet.

“Yes, Mr. Finch?”

It is impossible for a historian with a nice sense of values not to recognise the entry of George Finch, following immediately after that of J. Hamilton Beamish, as an anti-climax. Mr. Beamish filled the eye. An aura of authority went before him as the cloud of fire went before the Israelites in the desert. When you met J. Hamilton Beamish, something like a steam-hammer seemed to hit your consciousness and stun it long before he came within speaking-distance. In the case of George Finch nothing of this kind happened.

George looked what he was, a nice young small bachelor, of the type you see bobbing about the place on every side. One glance at him was enough to tell you that he had never written a Booklet and never would write a Booklet. In figure he was slim and slight; as to the face, pleasant and undistinguished. He had brown eyes which in certain circumstances could look like those of a stricken sheep; and his hair was of a light chestnut colour. It was possible to see his hair clearly, for he was not wearing his hat but carrying it in his hand.

He was carrying it reverently, as if he attached a high value to it. And this was strange, for it was not much of a hat. Once it may have been, but now it looked as if it had been both trodden on and kicked about.

“Mullett,” he said, regarding this relic with a dreamy eye, “take this hat and put it away.”

“Throw it away, sir?”

“Good heavens, no! Put it away—very carefully. Have you any tissue paper?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then wrap it up very carefully in tissue paper and leave it on the table in my sitting-room.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Pardon me for interrupting,” said a deprecating voice behind him, “but might I request a moment of your valuable time, Mr. Finch?”

Officer Garroway had left his fixed point and was standing in an attitude that seemed to suggest embarrassment. His mild eyes wore a somewhat timid expression.

“Forgive me if I intrude,” said Officer Garroway.

“Not at all,” said George.

“I am a policeman, sir.”

“So I see.”

“And,” said Officer Garroway sadly, “I have a rather disagreeable duty to perform, I fear. I would avoid it if I could reconcile the act with my conscience, but duty is duty. One of the drawbacks to the policeman’s life, Mr. Finch, is that it is not easy for him always to do the gentlemanly thing.”

“No doubt,” said George.

Mullett swallowed apprehensively. The hunted look had come back to his face. Officer Garroway eyed him with a gentle solicitude.

“I would like to preface my remarks,” he proceeded, “by saying that I have no personal animus against Mr. Mullett. I have seen nothing in my brief acquaintance with Mr. Mullett that leads me to suppose that he is not a pleasant companion and zealous in the performance of his work. Nevertheless, I think it right that you should know that he is an ex-convict.”

“An ex-convict!”

“Reformed,” said Mullett hastily.

“As to that, I cannot say,” said Officer Garroway. “I can but speak of what I know. Very possibly, as he asserts, Mr. Mullett is a reformed character. But this does not alter the fact that he has done his bit of time; and in pursuance of my duty I can scarcely refrain from mentioning this to the gentleman who is his present employer. The moment I was introduced to him I detected something oddly familiar about Mr. Mullett’s face and I have just recollected that I recently saw a photograph of him in the Rogues Gallery at Headquarters. You are possibly aware, sir, that convicted criminals are ‘mugged’—that is to say, photographed in various positions—at the commencement of their term of incarceration. This was done to Mr. Mullett some eighteen months ago when he was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment for an inside burglary job. May I ask how Mr. Mullett came to be in your employment?”

“He was sent to me by Mr. Beamish. Mr. Hamilton Beamish.”

“In that case, sir. I have nothing further to say,” said the policeman, bowing at the honoured name. “No doubt Mr. Beamish had excellent reasons for recommending Mr. Mullett. And, of course, as Mr. Mullett has long since expiated his offence, I need scarcely say that we of the Force have nothing against him. I merely considered it my duty to inform you of his previous activities in case you should have any prejudice against employing a man of his antecedents. I must now leave you, as my duties compel me to return to the station-house. Good afternoon, Mr. Finch.”

“Good afternoon.”

“Good day, Mr. Mullett. Pleased to have met you. You did not by any chance run into a young fellow named Joe the Gorilla while you were in residence at Sing-Sing? No? I’m sorry. He came from my home town. I should have liked news of Joe.”

Officer Garroway’s departure was followed by a lengthy silence. George Finch shuffled his feet awkwardly. He was an amiable young man and disliked unpleasant scenes. He looked at Mullett. Mullett looked at the sky.

“Er—Mullett,” said George.

“Sir?”

“This is rather unfortunate.”

“Most unpleasant for all concerned, sir.”

“I think Mr. Beamish might have told me.”

“No doubt he considered it unnecessary, sir. Being aware that I had reformed.”

“Yes, but even so . . . er—Mullett.”

“Sir?”

“The officer spoke of an inside burglary job. What was your exact—er—line?”

“I used to get a place as a valet, sir, and wait till I saw my chance and then skin out with everything I could lay my hands on.”

“You did, did you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, I do think Mr. Beamish might have dropped me a quiet hint. Good heavens! I may have been putting temptation in your way for weeks.”

“You have, sir—very serious temptation. But I welcome temptation, Mr. Finch. Every time I’m left alone with your pearl studs, I have a bout with the Tempter. ‘Why don’t you take them, Mullett?’ he says to me. ‘Why don’t you take them?’ It’s splendid moral exercise, sir.”

“I suppose so.”

“Yes, sir, it’s awful what that Tempter will suggest to me. Sometimes, when you’re lying asleep, he says: ‘Slip a sponge of chloroform under his nose, Mullett, and clear out with the swag!’ Just imagine it, sir.”

“I am imagining it.”

“But I win every time, sir. I’ve not lost one fight with that old Tempter since I’ve been in your employment, Mr. Finch.”

“All the same, I don’t believe you’re going to remain in my employment, Mullett.”

Mullett inclined his head resignedly.

“I was afraid of this, sir. The moment that flat-footed cop came on to this roof, I had a presentiment that there was going to be trouble. But I should appreciate it very much if you could see your way to reconsider, sir. I can assure you that I have completely reformed.”

“Religion?”

“No, sir. Love.”

The word seemed to touch some hidden chord in George Finch. The stern, set look vanished from his face. He gazed at his companion almost meltingly.

“Mullett! Do you love?”

“I do, indeed, sir. Fanny’s her name, sir. Fanny Welch. She’s a pickpocket.”

“A pickpocket!”

“Yes, sir. And one of the smartest girls in the business. She could take your watch out of your waistcoat, and you’d be prepared to swear she hadn’t been within a yard of you. It’s almost an art, sir. But she’s promised to go straight, if I will; and now I’m saving up to buy the furniture. So I do hope, sir, that you will reconsider. It would set me back if I fell out of a place just now.”

George wrinkled his forehead.

“I oughtn’t to.”

“But you will, sir?”

“It’s weak of me.”

“Not it, sir. Christian, I call it.”

George pondered.

“How long have you been with me, Mullett?”

“Just on a month, sir.”

“And my pearl studs are still there?”

“Still in the drawer, sir.”

“All right, Mullett. You can stay.”

“Thank you very much, indeed, sir.”

There was a silence. The setting sun flung a carpet of gold across the roof. It was the hour at which men become confidential.

“Love is very wonderful, Mullett!” said George Finch.

“Makes the world go round, I often say, sir.”

“Mullett.”

“Sir?”

“Shall I tell you something?”

“If you please, sir.”

“Mullett,” said George Finch, “I, too, love.”

“You surprise me, sir.”

“You may have noticed that I have been fussy about my clothing of late, Mullett?”

“Oh, no, sir.”

“Well, I have been, and that was the reason. She lives on East Seventy-Ninth Street. Mullett. I saw her first lunching at the Plaza with a woman who looked like Catherine of Russia. Her mother, no doubt.”

“Very possibly, sir.”

“I followed her home. I don’t know why I am telling you this, Mullett.”

“No, sir.”

“Since then I have haunted the sidewalk outside her house. Do you know East Seventy-Ninth Street?”

“Never been there, sir.”

“Well, fortunately it is not a very frequented thoroughfare, or I should have been arrested for loitering. Until to-day I have never spoken to her, Mullett.”

“But you did to-day, sir?

“Yes. Or, rather she spoke to me. She has a voice like the fluting of young birds in the springtime, Mullett.”

“Very agreeable, no doubt, sir.”

“Heavenly would express it better. It happened like this, Mullett. I was outside the house, when she came along, leading a Scotch terrier on a leash. At that moment a gust of wind blew my hat off and it was bowling past her, when she stopped it. She trod on it, Mullett.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Yes, this hat which you see in my hand, has been trodden on by Her. This very hat.”

“And then, sir?”

“In the excitement of the moment she dropped the leash and the Scotch terrier ran off round the corner in the direction of Brooklyn. I went in pursuit and succeeded in capturing it in Lexington Avenue. My hat dropped off again and was run over by a taxi-cab. But I retained my hold of the leash and eventually restored the dog to its mistress. She said—and I want you to notice this very carefully, Mullett—she said: ‘Oh, thank you so much!’ ”

“Did she, indeed, sir?”

“She did. Not merely ‘Thank you!’ or ‘Oh, thank you!’ but ‘Oh, thank you so much!’ ” George Finch fixed a penetrating stare on his employee. “I think that is significant, Mullett.”

“Extremely, sir.”

“If she had wished to end the acquaintance then and there, would she have spoken so warmly?”

“Impossible, sir.”

“And I’ve not told you all. Having said ‘Oh, thank you so much!’ she added ‘He is a naughty dog, isn’t he?’ You get the extraordinary subtlety of that, Mullett? The words ‘He is a naughty dog’ would have been a mere statement. But adding ‘Isn’t he?’ she invited my opinion. She gave me to understand that she would welcome discussion on the subject. Do you know what I am going to do, directly I have dressed, Mullett?”

“Dine, sir?”

“Dine!” George shuddered. “No! There are moments when the thought of food is an outrage to everything that raises man above the level of the beasts. As soon as I have dressed—and I shall dress very carefully—I am going to return to East Seventy-Ninth Street and I am going to ring the door-bell and I am going to go straight in and inquire after the dog. Hope it is none the worse for its adventure and so on. After all, it is only the civil thing. I mean, these Scotch terriers . . . delicate, highly-strung animals . . . Never can tell what effect unusual excitement may have on them. Yes, Mullett, that is what I propose to do. Brush my dress-clothes as you have never brushed them before.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Put me out a selection of ties. Say, a dozen.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And—did the bootlegger call this morning?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then mix me a very strong whisky-and-soda, Mullett,” said George Finch. “Whatever happens, I must be at my best to-night.”

IV

To George, sunk in a golden reverie, there entered some few minutes later, jarring him back to life, a pair of three-pound dumb-bells, which shot abruptly out of the unknown and came trundling across the roof at him with a repulsive, clumping sound that would have disconcerted Romeo. They were followed by J. Hamilton Beamish on all fours. Hamilton Beamish, who believed in the healthy body as well as the sound mind, always did half an hour’s open-air work with the bells of an evening; and, not for the first time, he had tripped over the top stair.

He recovered his balance, his dumb-bells and his spectacles in three labour-saving movements; and with the aid of the last-named was enabled to perceive George.

“Oh, there you are!” said Hamilton Beamish.

“Yes,” said George, “and . . .”

“What’s all this I hear from Mullett?” asked Hamilton Beamish.

“What,” inquired George simultaneously, “is all this I hear from Mullett?”

“Mullett says you’re fooling about after some girl up-town.”

“Mullett says you knew he was an ex-convict when you recommended him to me.”

Hamilton Beamish decided to dispose of this triviality before going on to more serious business.

“Certainly,” he said. “Didn’t you read my series in the Yale Review on the Problem of the Reformed Criminal? I point out very clearly that there is nobody with such a strong bias towards honesty as the man who has just come out of prison. It stands to reason. If you had been laid up for a year in hospital as the result of jumping off this roof, what would be the one outdoor sport in which, on emerging, you would be most reluctant to indulge? Jumping off roofs, undoubtedly.”

George continued to frown in a dissatisfied way.

“That’s all very well, but a fellow doesn’t want ex-convicts hanging about the home.”

“Nonsense! You must rid yourself of this old-fashioned prejudice against men who have been in Sing-Sing. Try to look on the place as a sort of university which fits its graduates for the problems of the world without. Morally speaking, such men are the student body. You have no fault to find with Mullett, have you?”

“No, I can’t say I have.”

“Does his work well?”

“Yes.”

“Not stolen anything from you?”

“No.”

“Then why worry? Dismiss the man from your mind. And now let me hear all about this girl of yours.”

“How do you know anything about it?”

“Mullett told me.”

“How did he know?”

“He followed you a couple of afternoons and saw all.”

George turned pink.

“I’ll go straight in and fire that man. The Snake!”

“You will do nothing of the kind. He acted as he did from pure zeal and faithfulness. He saw you go out, muttering to yourself. . . .”

“Did I mutter?” said George, startled.

“Certainly you muttered. You muttered, and you were exceedingly strange in your manner. So naturally Mullett, good, zealous fellow, followed you to see that you came to no harm. He reports that you spend a large part of your leisure goggling at some girl in Seventy-Ninth Street, East.”

George’s pink face turned a shade pinker. A sullen look came into it.

“Well, what about it?”

“That’s what I want to know—what about it?”

“Why shouldn’t I goggle?”

“Why should you?”

“Because,” said George Finch, looking like a stuffed frog, “I love her.”

“Nonsense!”

“It isn’t nonsense.”

“Have you ever read my booklet on The Marriage Sane?”

“No, I haven’t.”

“I show there that love is a reasoned emotion that springs from mutual knowledge, increasing over an extended period of time, and a community of tastes. How can you love a girl when you have never spoken to her and don’t even know her name?”

“I do know her name.”

“How?”

“I looked through the telephone directory till I found out who lived at Number 16, East Seventy-Ninth Street. It took me about a week, because . . .”

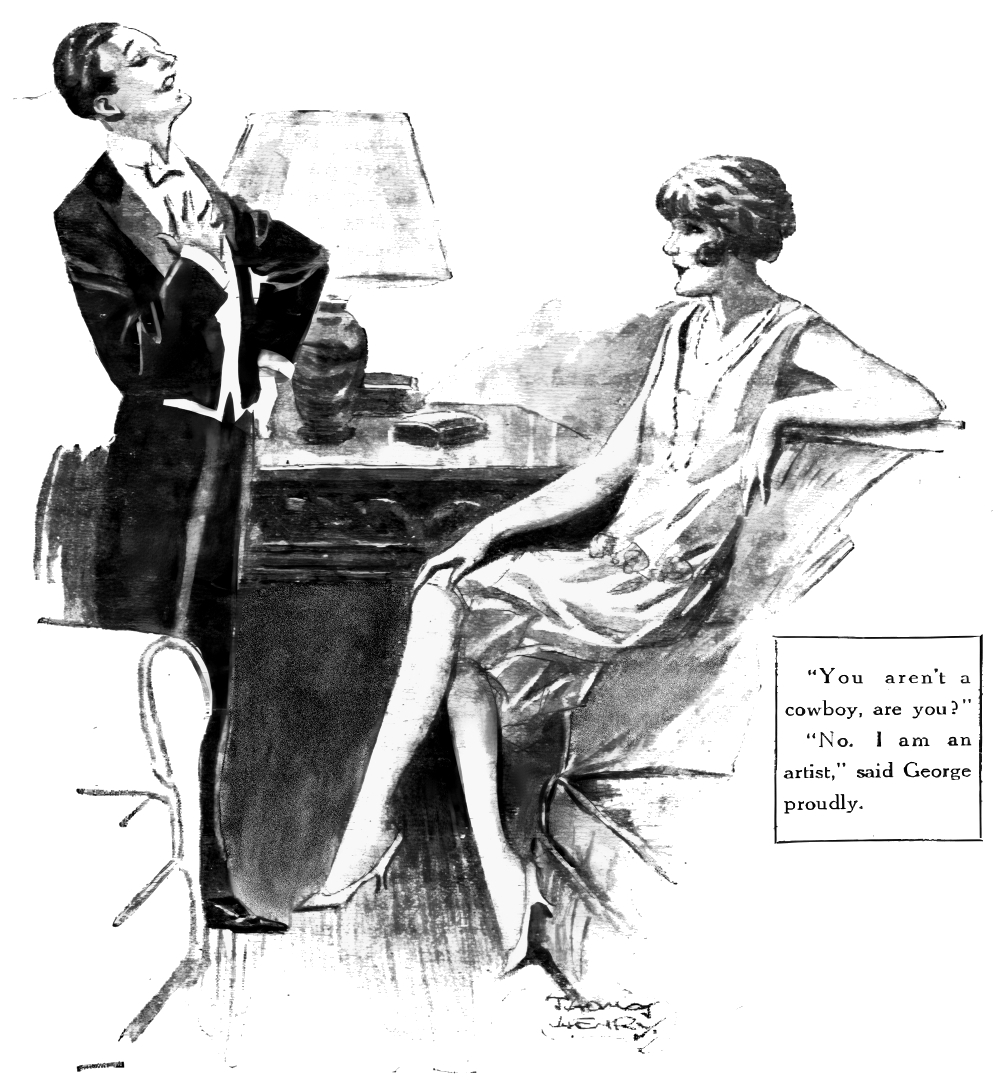

“Sixteen, East Seventy-Ninth Street? You don’t mean that this girl you’ve been staring at is little Molly Waddington?”

George started.

“Waddington is the name, certainly. That’s why I was such an infernal time getting to it in the book. Waddington, Sigsbee H.” George choked emotionally, and gazed at his friend with awed eyes. “Hamilton! Hammy, old man! You—you don’t mean to say you actually know her? Not positively know her?”

“Of course I know her. Know her intimately. Many’s the time I’ve seen her in her bath-tub.”

George quivered from head to foot.

“It’s a lie! A foul and contemptible . . .”

“When she was a child.”

“Oh, when she was a child?” George became calmer. “Do you mean to say you’ve known her since she was a child? Why, then you must be in love with her yourself.”

“Nothing of the kind.”

“You stand there and tell me,” said George incredulously, “that you have known this wonderful girl for many years and are not in love with her?”

“I do.”

George regarded his friend with a gentle pity. He could only explain this extraordinary statement by supposing that there was some sort of a kink in Hamilton Beamish. Sad, for in so many ways he was such a fine fellow.

“The sight of her has never made you feel that, to win one smile, you could scale the skies and pluck out the stars and lay them at her feet?”

“Certainly not. Indeed, when you consider that the nearest star is several million . . .”

“All right,” said George. “All right. Let it go. And now,” he went on, simply, “tell me all about her and her people and her house and her dog and what she was like as a child and when she first bobbed her hair and who is her favourite poet and where she went to school and what she likes for breakfast . . .”

Hamilton Beamish reflected.

“Well, I first knew Molly when her mother was alive.”

“Her mother is alive. I’ve seen her. A woman who looks like Catherine of Russia.”

“That’s her stepmother. Sigsbee H. married again just over a couple of years ago.”

“Tell me about Sigsbee H.”

Hamilton Beamish twirled a dumb-bell thoughtfully.

“Sigsbee H. Waddington,” he said, “is one of those men who must, I think, during the formative years of their boyhood have been kicked on the head by a mule. It has been well said of Sigsbee H. Waddington that, if men were dominoes, he would be the double-blank. One of the numerous things about him that rule him out of serious consideration by intelligent persons is the fact that he is a synthetic Westerner.”

“A synthetic Westerner?”

“It is a little known, but growing, subspecies akin to the synthetic Southerner—with which curious type you are doubtless familiar.”

“I don’t think I am.”

“Nonsense. Have you never been in a restaurant where the orchestra played Dixie?”

“Of course.”

“Well, then, on such occasions you will have noted that the man who gives a rebel yell and springs on his chair and waves a napkin with flashing eyes is always a suit-and-cloak salesman named Rosenthal or Bechstein who was born in Passaic, New Jersey, and has never been farther South than Far Rockaway. That is the synthetic Southerner.”

“I see.”

“Sigsbee H. Waddington is a synthetic Westerner. His whole life, with the exception of one summer vacation when he went to Maine, has been spent in New York State; and yet, to listen to him, you would think he was an exiled cowboy. I fancy it must be the effect of seeing too many Westerns in the movies. Sigsbee Waddington has been a keen supporter of the motion-pictures from their inception; and was, I believe, one of the first men in this city to hiss the villain. Whether it was Tom Mix who caused the trouble, or whether his weak intellect was gradually sapped by seeing William S. Hart kiss his horse, I cannot say; but the fact remains that he now yearns for the great open spaces and, if you want to ingratiate yourself with him, all you have to do is to mention that you were born in Idaho—a fact which I hope that, as a rule, you carefully conceal.”

“I will,” said George enthusiastically. “I can’t tell you how grateful I am to you, Hamilton, for giving me this information.”

“You needn’t be. It will do you no good whatever. When Sigsbee Waddington married for the second time he to all intents and purposes sold himself down the river. To call him a cipher in the home would be to give a too glowing picture of his importance. He does what his wife tells him—that and nothing more. She is the one with whom you want to ingratiate yourself.”

“How can this be done?”

“It can’t be done. Mrs. Sigsbee Waddington is not an easy woman to conciliate.”

“A tough baby?” inquired George anxiously.

Hamilton Beamish frowned.

“I dislike the expression. It is the sort of expression Mullett would use; and I know few things more calculated to make a thinking man shudder than Mullett’s vocabulary. Nevertheless, in a certain crude, horrible way it does describe Mrs. Waddington. There is an ancient belief in Thibet that mankind is descended from a demoness named Drasrinmo and a monkey. Both Sigsbee H. and Mrs. Waddington do much to bear out this theory. I am loth to speak ill of a woman, but it is no use trying to conceal the fact that Mrs. Waddington is a bounder and a snob and has a soul like the underside of a flat stone. She worships wealth and importance. She likes only the rich and the titled. As a matter of fact, I happen to know that there is an English lord hanging about the place whom she wants Molly to marry.”

“Over my dead body,” said George.

“That could no doubt be arranged. My poor George,” said Hamilton Beamish, laying a dumb-bell affectionately on his friend’s head, “you are taking on too big a contract. You are going out of your class. It is not as if you were one of these dashing young Lochinvar fellows. You are mild and shy. You are diffident and timid. I class you among Nature’s white mice. It would take a woman like Mrs. Sigsbee Waddington about two and a quarter minutes to knock you for a row of Portuguese ash-cans—er, as Mullett would say,” added Hamilton Beamish with a touch of confusion.

“She couldn’t eat me,” said George valiantly.

“I don’t know so much. She is not a vegetarian.”

“I was thinking,” said George, “that you might take me round and introduce me . . .”

“And have your blood on my head? No, no.”

“What do you mean, my blood? You talk as if this woman were a syndicate of gunmen. I’m not afraid of her. To get to know Molly,” George gulped, “I would fight a mad bull.”

Hamilton Beamish was touched. This great man was human.

“These are brave words, George. You extort my admiration. I disapprove of the reckless, unconsidered way you are approaching this matter and I still think you would be well advised to read The Marriage Sane and get a proper estimate of Love; but I cannot but like your spirit. If you really wish it, therefore, I will take you round and introduce you to Mrs. Sigsbee H. Waddington. And may the Lord have mercy on your soul.”

“Hamilton! To-night?”

“Not to-night. I am lecturing to the West Orange Daughters of Minerva to-night on ‘The Modern Drama.’ Some other time.”

“Then to-night,” said George, blushing faintly, “I think I may as well just stroll round Seventy-Ninth Street way and—er—well, just stroll round.”

“What is the good of that?”

“Well, I can look at the house, can’t I?”

“Young blood!” said Hamilton Beamish indulgently. “Young blood!”

He poised himself firmly on his No-Jars and swung the dumb-bells in a forceful arc.

V

“Mullett,” said George.

“Sir?”

“Have you pressed my dress clothes?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And brushed them?”

“Yes, sir.”

“My ties—are they laid out?”

“In a neat row, sir.”

George coughed.

“Mullett.”

“Sir?”

“You recollect the little chat we were having just now?”

“Sir?”

“About the young lady I—er——”

“Oh, yes, sir.”

“I understand you have seen her.”

“Just a glimpse, sir.”

George coughed again.

“Ah—rather attractive, Mullett, didn’t you think?”

“Extremely, sir. Very cuddly.”

“The exact adjective I would have used myself, Mullett!”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Cuddly! A beautiful word.”

“I think so, sir.”

George coughed for the third time.

“A lozenge, sir?” said Mullett, solicitously.

“No, thank you.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Mullett!”

“Sir?”

“I find that Mr. Beamish is an intimate friend of this young lady.”

“Fancy that, sir!”

“He is going to introduce me.”

“Very gratifying, I am sure, sir.”

George sighed dreamily.

“Life is very sweet, Mullett.”

“For those that like it, sir—yes, sir.”

“Lead me to the ties,” said George.

CHAPTER TWO

At the hour of seven-thirty, just when George Finch was trying out his fifth tie, a woman stood pacing the floor in the Byzantine boudoir at Number Sixteen, Seventy-Ninth Street, East.

At first sight this statement may seem contradictory. Is it possible, the captious critic may ask, for a person simultaneously to stand and pace the floor? The answer is yes, if he or she is sufficiently agitated as to the soul. You do it by placing yourself on a given spot and scrabbling the feet alternately like a cat kneading a hearthrug. It is sometimes the only method by which strong women can keep from having hysterics.

Mrs. Sigsbee H. Waddington was a strong woman. In fact, so commanding was her physique that a stranger might have supposed her to be one in the technical, or circus, sense. She was not tall, but she had bulged so generously in every possible direction that, when seen for the first time, she gave the impression of enormous size. No theatre, however little its programme had managed to attract the public, could be said to be “sparsely filled” if Mrs. Waddington had dropped in to look at the show. Public speakers, when Mrs. Waddington was present, had the illusion that they were addressing most of the population of the United States. And when she went to Carlsbad or Aix-les-Bains to take the waters, the authorities huddled together nervously and wondered if there would be enough to go round.

Her growing bulk was a perpetual sorrow—one of many—to her husband. When he had married her, she had been slim and svelte. But she had also been the relict of the late P. Homer Horlick, the Cheese King; and he had left her several million dollars. Most of the interest accruing from this fortune she had, so it sometimes seemed to Sigsbee H. Waddington, spent on starchy foods.

Mrs. Waddington stood and paced the floor and, presently, the door opened.

“Lord Hunstanton,” announced Ferris, the butler.

The standard of male looks presented up to the present in this story has not been high; but the man who now entered did much to raise the average. He was tall and slight and elegant, with frank, blue eyes—one of them preceded by an eyeglass—and one of those clipped moustaches. His clothes had been cut by an inspired tailor and pressed by a genius. His tie was simply an ethereal white butterfly, straight from heaven, that hovered over the collar stud as if it were sipping pollen from some exotic flower. (George Finch, now working away at number eight and having just got it creased in four places, would have screamed hoarsely with envy at the sight of that tie.)

“Well, here I am,” said Lord Hunstanton. He paused for a moment, then added: “What, what!” as if he felt that it was expected of him.

“It was so kind of you to come,” said Mrs. Waddington, pivoting on her axis and panting like a hart after the water-brooks.

“Not at all.”

“I knew I could rely on you.”

“You have only to command.”

“You are such a true friend, though I have known you only such a short time.”

“Is anything wrong?” asked Lord Hunstanton.

He was more than a little surprised to find himself at seven-forty in a house where he had been invited to dine at half-past eight. His dressing had been interrupted by a telephone-call from Mrs. Waddington’s butler, begging him to come round at once; and, noting his hostess’s agitation, he hoped that nothing had gone wonky with the dinner.

“Everything is wrong!”

Lord Hunstanton sighed inaudibly. Did this mean cold meat and a pickle?

“Sigsbee is having one of his spells!”

“You mean he has been taken ill?”

“Not ill. Fractious.” Mrs. Waddington gulped. “It’s so hard that this should have occurred on the night of an important dinner-party, after you have taken such trouble with his education. I have said a hundred times that, since you came, Sigsbee has been a different man. He knows all the forks now and can even talk intelligently about soufflés.”

“I am only too glad if any little pointers I have been able to. . . .”

“And when I take him out for a run he always walks on the outside of the pavement. And here he must go, on the night of my biggest dinner-party, and have one of his spells.”

“What is the trouble? Is he violent?”

“No. Sullen.”

“What about?”

Mrs. Waddington’s mouth set in a hard line.

“Sigsbee is pining for the West again!”

“You don’t say so?”

“Yes, sir, he’s pining for the great wide-open spaces of the West. He says the East is effete and he wants to be out there among the silent canyons where men are men. If you want to know what I think, somebody’s been feeding him Zane Grey.”

“Can nothing be done?”

“Yes—in time. I can get him right if I’m given time, by stopping his pocket money. But I need time and here he is, an hour before my important dinner, with some of the most wealthy and exclusive people in New York expected at any moment, refusing to put on his dress-clothes and saying that all a man that is a man needs is to shoot his bison and cut off a steak and cook it by the light of the western stars. And what I want to know is, what am I to do?”

Lord Hunstanton twisted his moustache thoughtfully.

“Very perplexing.”

“I thought if you went and had a word with him . . .”

“I doubt if it would do any good. I suppose you couldn’t dine without him?”

“It would make us thirteen.”

“I see.” His lordship’s face brightened. “I’ve got it! Send Miss Waddington to reason with him.”

“Molly? You think he would listen to her?”

“He is very fond of her.”

Mrs. Waddington reflected.

“It’s worth trying. I’ll go up and see if she is dressed. She is a dear girl, isn’t she, Lord Hunstanton?”

“Charming, charming.”

“I’m sure I’m as fond of her as if she were my own daughter.”

“No doubt.”

“Though, of course, dearly as I love her, I am never foolishly indulgent. So many girls to-day are spoiled by foolish indulgence.”

“True.”

“My great wish, Lord Hunstanton, is one day to see her happily married to some good man.”

His Lordship closed the door behind Mrs. Waddington and stood for some moments in profound thought. He may have been wondering what was the earliest he could expect a cocktail, or he may have been musing on some deeper subject—if there is a deeper subject.

II

Mrs. Waddington navigated upstairs, and paused before a door near the second landing.

“Molly!”

“Yes, mother?”

Mrs. Waddington was frowning as she entered the room. How often she had told this girl to call her “mater”!

But this was a small point, and not worth mentioning at a time like the present. She sank into a chair with a creaking groan. Strong woman though she was, Mrs. Sigsbee Waddington, like the chair, was near to breaking down.

“Good heavens, mother! What’s the matter?”

“Send her away,” muttered Mrs. Waddington, nodding at her stepdaughter’s maid.

“All right, mother. I shan’t want you any more, Julie. I can manage now. Shall I get you a glass of water, mother?”

Molly looked at her suffering step-parent with gentle concern, wishing that she had something stronger than water to offer. But her late mother had brought her up in that silly, stuffy way in which old-fashioned mothers used to bring up their daughters: and, incredible as it may seem in these enlightened days, Molly Waddington had reached the age of twenty without forming even a nodding acquaintance with alcohol. Now, no doubt, as she watched her stepmother gulping before her like a moose that has had trouble in the home, she regretted that she was not one of those sensible modern girls who always carry a couple of shots around with them in a jewelled flask.

But, though a defective upbringing kept her from being useful in this crisis, nobody could deny that, as she stood there half-dressed for dinner, Molly Waddington was extremely ornamental. If George Finch could have seen her at that moment . . . But then if George Finch had seen her at that moment, he would immediately have shut his eyes like a gentleman: for there was that about her costume, in its present stage of development, which was not for the male gaze.

Still, however quickly he had shut his eyes, he could not have shut them rapidly enough to keep from seeing that Mullett, in his recent remarks on an absorbing subject, had shown an even nicer instinct for the mot juste than he had supposed. Beyond all chance for evasion or doubt, Molly Waddington was cuddly. She was wearing primrose knickers, and her silk-stockinged legs tapered away to little gold shoes. Her pink fingers were clutching at a blue dressing-jacket with swansdown trimming. Her bobbed hair hung about a round little face with a tip-tilted little nose. Her eyes were large, her teeth small and white and even. She had a little brown mole on the back of her neck and—in short, to sum the whole thing up, if George Finch could have caught even the briefest glimpse of her at this juncture, he must inevitably have fallen over sideways, yapping like a dog.

Mrs. Waddington’s breathing had become easier, and she was sitting up in her chair with something like the old imperiousness.

“Molly,” said Mrs. Waddington, “have you been giving your father Zane Grey?”

“Of course not.”

“You’re sure?”

“Quite. I don’t think there’s any Zane Grey in the house.”

“Then he’s been sneaking out and seeing Tom Mix again,” said Mrs. Waddington.

“You don’t mean . . .?”

“Yes! He’s got one of his spells.”

“A bad one?”

“So bad that he refuses to dress for dinner. He says that if the boys”—Mrs. Waddington shuddered—“if the boys don’t like him in a flannel shirt, he won’t come in to dinner at all. And Lord Hunstanton suggested that I should send you to reason with him.”

“Lord Hunstanton? Has he arrived already?”

“I telephoned for him. I am coming to rely on Lord Hunstanton more and more every day. What a dear fellow he is!”

“Yes,” said Molly, a little dubiously. She was not fond of his lordship.

“So handsome.”

“Yes.”

“Such breeding.”

“I suppose so.”

“I should be very happy,” said Mrs. Waddington, “if a man like Lord Hunstanton asked you to be his wife.”

Molly fiddled with the trimming of her dressing-jacket. This was not the first time the subject had come up between her step-mother and herself. A remark like the one just recorded was Mrs. Waddington’s idea of letting fall a quiet hint.

“Well——” said Molly.

“What do you mean, well?”

“Well, don’t you think he’s rather stiff.”

“Stiff!”

“Don’t you find him a little starchy?”

“If you mean that Lord Hunstanton’s manners are perfect, I agree with you.”

“I’m not sure that I like a man’s manners to be too perfect,” said Molly meditatively. “Don’t you think a shy man can be rather attractive?” She scraped the toe of one gold shoe against the heel of the other. “The sort of man I think I should rather like,” she said, a dreamy look in her eyes, “would be a sort of slimmish, smallish man with nice brown eyes and rather gold-y, chestnutty hair, who kind of looks at you from a distance because he’s too shy to speak to you and, when he does get a chance to speak to you, sort of chokes and turns pink and twists his fingers and makes funny noises and trips over his feet and looks rather a lamb and . . .”

Mrs. Waddington had risen from her chair like a storm-cloud brooding over a countryside.

“Molly!” she cried. “Who is this young man?”

“Why nobody, of course! Just someone I sort of imagined.”

“Oh!” said Mrs. Waddington, relieved. “You spoke as if you knew him.”

“What a strange idea!”

“If any young man ever does look at you and make funny noises, you will ignore him.”

“Of course.”

Mrs. Waddington started.

“All this nonsense you have been talking has made me forget about your father. Put on your dress and go down to him at once. Reason with him! If he refuses to come in to dinner, we shall be thirteen, and my party will be ruined.”

“I’ll be ready in a couple of minutes. Where is he?”

“In the library.”

“I’ll be right down.”

“And, when you have seen him, go into the drawing-room and talk to Lord Hunstanton. He is all alone.”

“Very well, mother.”

“Mater.”

“Mater,” said Molly.

She was one of those nice, dutiful girls.

III

In addition to being a nice, dutiful girl, Molly Waddington was also a persuasive, wheedling girl. Better proof of this statement can hardly be afforded than by the fact that, as the clocks were pointing to ten minutes past eight, a red-faced, angry little man with stiff grey hair and a sulky face shambled down the stairs of Number sixteen, East Seventy-Ninth Street, and, pausing in the hall, subjected Ferris, the butler, to an offensive glare. It was Sigsbee H. Waddington, fully if sloppily dressed in the accepted mode of gentlemen of social standing about to dine.

The details of any record performance are always interesting, so it may be mentioned that Molly had reached the library at seven minutes to eight. She had started wheedling at exactly six minutes and forty-five seconds to the hour. At seven fifty-four Sigsbee Waddington had begun to weaken. At seven fifty-seven he was fighting in the last ditch; and at seven fifty-nine, vowing he would ne’er consent, he consented.

Into the arguments used by Molly we need not enter fully. It is enough to say that, if a man loves his daughter dearly, and if she comes to him and says that she has been looking forward to a certain party and is wearing a new dress for that party, and if, finally, she adds that should he absent himself from that party, the party and her pleasure will be ruined—then, unless the man has a heart of stone, he will give in. Sigsbee Waddington had not a heart of stone. Many good judges considered that he had a head of concrete, but nobody had ever disparaged his heart. At eight precisely he was in his bedroom, shovelling on his dress clothes; and now, at ten minutes past, he stood in the hall and looked disparagingly at Ferris.

Sigsbee Waddington thought Ferris was an over-fed wart.

Ferris thought Sigsbee Waddington ought to be ashamed to appear in public in a tie like that.

But thoughts are not words. What Ferris actually said was:

“A cocktail, sir?”

And what Sigsbee Waddington actually said was:

“Yup! Gimme!”

There was a pause. Mr. Waddington, still unsoothed, continued to glower. Ferris, resuming his marmoreal calm, had begun to muse once more, as was his habit when in thought, on Brangmarley Hall, Little-Sleeping-in-the-Wold, Salop, England, where he had spent the early happy days of his butlerhood.

“Ferris!” said Mr. Waddington at length.

“Sir?”

“You ever been out West, Ferris?”

“No, sir.”

“Ever want to go?”

“No, sir.”

“Why not?” demanded Mr. Waddington belligerently.

“I understand that in the Western States of America, sir, there is a certain lack of comfort, and the social amenities are not rigorously observed.”

“Gangway!” said Mr. Waddington, making for the front door. He felt stifled. He wanted air. He yearned, if only for a few brief instants, to be alone with the silent stars.

It would be idle to deny that, at this particular moment, Sigsbee H. Waddington was in a dangerous mood. The history of nations shows that the wildest upheavals come from those peoples that have been most rigorously oppressed: and it is so with individuals. There is no man so terrible in his spasmodic fury as the hen-pecked husband during his short spasms of revolt. Even Mrs. Waddington recognised that, no matter how complete her control normally, Sigsbee H., when having one of his spells, practically amounted to a rogue elephant. Her policy was to keep out of his way till the fever passed, and then to discipline him severely.

As Sigsbee Waddington stood on the pavement outside his house, drinking in the dust-and-gasoline mixture which passes for air in New York and scanning the weak imitation stars which are the best the East provides, he was grim and squiggle-eyed and ripe for murders, stratagems and spoils. Molly’s statement that there was no Zane Grey in the house had been very far from the truth. Sigsbee Waddington had his private store, locked away in a secret cupboard, and since early morning Riders of the Purple Sage had hardly ever been out of his hand. During the afternoon, moreover, he had managed to steal away to a motion-picture house on Sixth Avenue where they were presenting Henderson Hoover and Sara Svelte in That L’il Gal from the Bar B Ranch. Sigsbee Waddington, as he stood on the pavement, was clad in dress-clothes and looked like a stage waiter, but at heart he was wearing chaps and a Stetson hat and people spoke of him as Two-Gun Thomas.

A large car drew up at the curb, and Mr. Waddington moved a step or two away. A fat man alighted and helped his fatter wife out. Mr. Waddington recognised them. B. and Mrs. Brewster Bodthorne. B. Brewster was the first vice-president of Amalgamated Tooth Brushes, and rolled in money.

“Pah!” muttered Mr. Waddington, sickened to the core.

The pair vanished into the house, and presently another car arrived followed by another still more sumptuous. Consolidated Pop-Corn and wife emerged, and then United Beef and daughter. A consignment worth on the hoof between eighty and a hundred million.

“How long?” moaned Mr. Waddington. “How long?”

And then, as the door closed, he was aware of a young man behaving strangely on the pavement some few feet away from him.

IV

The reason why George Finch—for it was he—was behaving strangely was that he was a shy young man and consequently unable to govern his movements by the light of pure reason. The ordinary tough-skinned everyday young fellow with a face of brass and the placid gall of an Army mule would, of course, if he had decided to pay a call upon a girl in order to make inquiries about her dog, have gone right ahead and done it. He would have shot his cuffs and straightened his tie and then trotted up the steps and punched the front-door bell. Not so the diffident George.

George’s methods were different. Graceful, and in their way, pretty to watch, but different. First, he stood for some moments on one foot staring at the house. Then, as if some friendly hand had dug three inches of a meat-skewer into the flesh of his leg, he shot forward in a spasmodic bound. Checking this as he reached the steps, he retreated a pace or two and once more became immobile. A few moments later, the meat-skewer had got to work again and he had sprung up the steps, only to leap backwards once more on to the sidewalk.

When Mr. Waddington first made up his mind to accost him, he had begun to walk round in little circles, mumbling to himself.

Sigsbee Waddington was in no mood for this sort of thing. It was the sort of thing, he felt bitterly, which could happen only in this degraded East. Out West, men are men and do not dance tangoes by themselves on front doorsteps. Venters, the hero of Riders of the Purple Sage, he recalled, had been described by the author as standing “tall and straight, his wide shoulders flung back, with the muscles of his arms rippling and a blue flame of defiance in his gaze.” How different, felt Mr. Waddington, from this imbecile young man who seemed content to waste life’s springtime playing solitary round games in the public streets.

“Hey!” he said sharply.

The exclamation took George amidships just as he had returned to the standing-on-one-leg position. It caused him to lose his balance, and if he had not adroitly clutched Mr. Waddington by the left ear, it is probable that he would have fallen.

“Sorry,” said George, having sorted himself out.

“What’s the use of being sorry?” growled the injured man, tenderly feeling his ear. “And what the devil are you doing, anyway?”

“Just paying a call,” explained George.

“Doing a what?”

“I’m paying a formal call at this house.”

“Which house?”

“This one. Number sixteen. Waddington, Sigsbee H.”

Mr. Waddington regarded him with unconcealed hostility.

“Oh, you are, are you? Well, it may interest you to learn that I am Sigsbee H. Waddington, and I don’t know you from Adam. So now!”

George gasped.

“You are Sigsbee H. Waddington?” he said reverently.

“I am.”

George was gazing at Molly’s father as at some beautiful work of art—a superb painting, let us say—the sort of thing which connoisseurs fight for and which finally gets knocked down to Dr. Rosenbach for three hundred thousand dollars. Which will give the reader a rough idea of what love can do: for, considered in a calm and unbiassed spirit, Sigsbee Waddington was little, if anything, to look at.

“Mr. Waddington,” said George, “I am proud to meet you.”

“You’re what?”

“Proud to meet you.”

“What of it?” said Sigsbee Waddington, churlishly.

“Mr. Waddington,” said George, “I was born in Idaho.”

Much has been written of the sedative effect of pouring oil on the raging waters of the ocean and it is on record that the vision of the Holy Grail, sliding athwart a rainbow, was generally sufficient to still the most fiercely warring passions of young knights in the Middle Ages. But never since history began can there have been so sudden a change from red-eyed hostility to smiling benevolence as occurred now in Sigsbee H. Waddington. As George’s words, like some magic spell, fell upon his ears, he forgot that one of those ears was smarting badly as the result of the impulsive clutch of this young man before him. Wrath melted from his soul like dew from a flower beneath the sun. He beamed on George. He pawed George’s sleeve with a paternal hand.

“You really come from the West?” he cried.

“I do.”

“From God’s own country? From the great wonderful West with its wide-open spaces where a red-blooded man can fill his lungs with the breath of freedom?”

It was not precisely the way George would have described East Gilead, which was a stuffy little hamlet with a poorish water supply and one of the worst soda-fountains in Idaho, but he nodded amiably.

Mr. Waddington dashed a hand across his eyes.

“The West! Why, it’s like a mother to me! I love every flower that blooms on the broad bosom of its sweeping plains, every sun-kissed peak of its everlasting hills.”

George said he did, too.

“Its beautiful valleys, mystic in their transparent, luminous gloom, weird in the quivering, golden haze of the lightning that flickers over them.”

“Ah!” said George.

“The dark spruces tipped with glimmering lights! The aspens bent low in the wind, like waves in a tempest at sea!”

“Can you beat them?” said George.

“The forest of oaks tossing wildly and shining with gleams of fire!”

“What could be sweeter?” said George.

“Say, listen,” said Mr. Waddington. “You and I must see more of each other. Come and have a bite of dinner!”

“Now?”

“Right this very minute. We’ve got a few of these puny-souled Eastern millionaires putting on the nose-bag with us to-night, but you won’t mind them. We’ll just look at ’em and despise ’em. And after dinner you and I will slip off to my study and have a good chat.”

“But won’t Mrs. Waddington object to an unexpected guest at the last moment?”

Mr. Waddington expanded his chest and tapped it spaciously.

“Say, listen—what’s your name?—Finch?—say, listen, Finch, do I look like the sort of man who’s bossed by his wife?”

It was precisely the sort of man that George thought he did look like, but this was not the moment to say so.

“It’s very kind of you,” he said.

“Kind? Say, listen, if I was riding along those illimitable prairies and got storm-bound outside your ranch, you wouldn’t worry about whether you were being kind when you asked me in for a bite, would you? You’d say, ‘Step right in, pardner! The place is yours.’ Very well, then!”

Mr. Waddington produced a latch-key.

“Ferris,” said Mr. Waddington in the hall, “tell those galoots down in the kitchen to set another place at table. A pard of mine from the West has happened in for a snack.”

CHAPTER III

The perfect hostess makes a point of never displaying discomposure. In times of trial she aims at the easy repose of manner of a Red Indian at the stake. Nevertheless, there was a moment when, as she saw Sigsbee H. caracole into the drawing-room with George and heard him announce in a ringing voice that this fine young son of the western prairies had come to take pot-luck, Mrs. Waddington indisputably reeled.

She recovered herself. All the woman in her was urging her to take Sigsbee H. by his outstanding ears and shake him till he came unstuck, but she fought the emotion down. Gradually her glazed eye lost its dead-fishy look. Like Death in the poem, she “grinned horrible a ghastly smile.” And it was with a well-assumed graciousness that she eventually extended to George the quivering right hand which, had she been a less highly civilised woman, would about now have been landing on the side of her husband’s head, swung from the hip.

“Chahmed!” said Mrs. Waddington. “So very, very glad that you were able to come, Mr.——”

She paused and George, eyeing her mistily, gathered that she wished to be informed of his name. He would have been glad to supply the information, but unfortunately at the moment he had forgotten it himself. He had a dim sort of idea that it began with an F. or a G., but beyond that his mind was a blank.

The fact was that, in the act of shaking hands with his hostess, George Finch had caught sight of Molly and the spectacle had been a little too much for him.

Molly was wearing the new evening-dress of which she had spoken so feelingly to her father at their recent interview and it seemed to George as if the scales had fallen from his eyes and he was seeing her for the first time. Before, in a vague way, he had supposed that she possessed arms and shoulders and hair; but it was only at this moment that he perceived how truly these arms and those shoulders and that hair were arms and shoulders and hair in the deepest and holiest sense of the words. It was as if a goddess had thrown aside the veil. It was as if a statue had come to life. It was as if . . . well, the point we are trying to make is that George Finch was impressed. His eyes enlarged to the dimensions of saucers; the tip of his nose quivered like a rabbit’s; and unseen hands began to pour iced water down his spine.

Mrs. Waddington, having given him one long, steady look that blistered his forehead, turned away and began to talk to a soda-water magnate. She had no real desire to ascertain George’s name, though she would have read it with pleasure on a tombstone.

“Dinner is served,” announced Ferris, the butler, appearing noiselessly like a Djinn summoned by the rubbing of a lamp.

George found himself swept up in the stampede of millionaires. He was still swallowing feebly.

There are few things more embarrassing to a shy and sensitive young man than to be present at a dinner-party where something seems to tell him that he is not really wanted. The something that seemed to tell George Finch he was not really wanted at to-night’s festive gathering was Mrs. Waddington’s eye, which kept shooting down the table at intervals and reducing him to pulp at those very moments when he was beginning to feel that, if treated with gentle care and kindness, he might eventually recover.

It was an eye that, like a thermos flask, could be alternately extremely hot and intensely cold. When George met it during the soup course he had the feeling of having encountered a simoom while journeying across an African desert. When, on the other hand, it sniped him as he toyed with his fish, his sensations were those of a searcher for the Pole who unexpectedly bumps into a blizzard. But, whether it was cold or hot, there was always in Mrs. Waddington’s gaze one constant factor—a sort of sick loathing which nothing that he could ever do, George felt, would have the power to allay. It was the kind of look which Sisera might have surprised in the eye of Jael, the wife of Heber, had he chanced to catch it immediately before she began operations with the spike. George had made one new friend that night, but not two.

The consequence was that as regards George Finch’s contribution to the feast of wit and flow of soul at that dinner-party we have nothing to report. He uttered no epigrams. He told no good stories. Indeed, the only time he spoke at all was when he said “Sherry” to the footman when he meant “Hock.”

Even, however, had the conditions been uniformly pleasant, it is to be doubted whether he would have really dominated the gathering. Mrs. Waddington, in her selection of guests, confined herself to the extremely wealthy; and, while the conversation of the extremely wealthy is fascinating in its way, it tends to be a little too technical for the average man.

With the soup, someone who looked like a cartoon of Capital in a Socialistic paper said he was glad to see that Westinghouse Common were buoyant again. A man who might have been his brother agreed that they had firmed up nicely at closing. Whereas Wabash Pref. A, falling to 73⅞, caused shakings of the head. However, one rather liked the look of Royal Dutch Oil Ordinaries at 54¾.

With the fish, United Beef began to tell a neat, though rather long, story about the Bolivian Land Concession, the gist of which was that the Bolivian Oil and Land Syndicate, acquiring from the Bolivian Government the land and prospecting concessions of Bolivia, would be known as Bolivian Concessions, Ltd., and would have a capital of one million dollars in two hundred thousand five-dollar “A” shares and two hundred thousand half-dollar “B” shares; and that, while no cash payment was to be made to the vendor syndicate, the latter was being allotted the whole of the “B” shares as consideration for the concession. And—this was where the raconteur made his point—the “B” shares were to receive half the divisible profits and to rank equal with the “A” shares in any distribution of assets.

The story went well and conversation became general. There was a certain amount of good-natured chaff about the elasticity of the form of credit handled by the Commercial Banks, and once somebody raised a laugh with a sly retort about the Reserve against Circulation and Total Deposits. On the question of the collateral liability of shareholders, however, argument ran high; and it was rather a relief when, as tempers began to get a little heated, Mrs. Waddington gave the signal and the women left the table.

Coffee having been served and cigars lighted, the magnates drew together at the end of the table where Mr. Waddington sat. But Mr. Waddington, adroitly side-stepping, left them and came down to George.

“Out West,” said Mr. Waddington in a rumbling undertone, malevolently eyeing Amalgamated Tooth-brushes, who had begun to talk about the Mid-Continent Fiduciary Conference at St. Louis, “they would shoot at that fellow’s feet.”

George agreed that such behaviour could reflect nothing but credit on the West.

“These Easterners make me tired,” said Mr. Waddington.

George confessed to a similar fatigue.

“When you think that at this very moment out in Utah and Arizona,” said Mr. Waddington, “strong men are packing their saddlebags and making them secure with their lassoes you kind of don’t know whether to laugh or cry, do you?”

That was the very problem, said George.

“Say, listen,” said Mr. Waddington “I’ll just push these pot-bellied guys off upstairs, and then you and I will sneak off to my study and have a real talk.”

II

Nothing spoils a tête-à-tête chat between two newly-made friends more than a disposition towards reticence on the part of the senior of the pair; and it was fortunate, therefore, that, by the time he found himself seated opposite to George in his study, the heady influence of Zane Grey and the rather generous potations in which he had indulged during dinner had brought Sigsbee H. Waddington to quite a reasonably communicative mood. He had reached the stage when men talk disparagingly about their wives.

He tapped George on the knee, informed him three times that he liked his face, and began.

“You married, Winch?”

“Finch,” said George.

“How do you mean, Finch?” asked Mr. Waddington, puzzled.

“My name is Finch.”

“What of it?”

“You called me Winch.”

“Why?”

“I think you thought it was my name.”

“What was?”

“Winch.”

“You said just now it was Finch.”

“Yes, it is. I was saying . . .”

Mr. Waddington tapped him on the knee once more.

“Young man,” he said, “pull yourself together. If your name is Finch, why pretend that it is Winch? I don’t like this shiftiness. It does not come well from a Westerner. Leave this petty shilly-shallying to Easterners like that vile rabble of widow-and-orphan oppressors upstairs, all of whom have got incipient Bright’s Disease. If your name is Pinch, admit it like a man. Let your yea be yea and your nay be nay,” said Mr. Waddington a little severely, holding a match to the fountain-pen which, as will happen to the best of us in moments of emotion, he had mistaken for his cigar.

“As a matter of fact, I’m not,” said George.

“Not what?”

“Married.”

“I never said you were.”

“You asked me if I was.”

“Did I?”

“Yes.”

“You’re sure of that?” said Mr. Waddington keenly.

“Quite. Just after we sat down, you asked me if I was married.”

“And your reply was . . .?”

“No.”

Mr. Waddington breathed a sigh of relief.

“Now we have got it straight at last,” he said, “and why you beat about the bush like that, I cannot imagine. Well, what I say to you, Pinch—and I say it very seriously as an older, wiser, and better-looking man—is this.” Mr. Waddington drew thoughtfully at the fountain-pen for a moment. “I say to you, Pinch, be very careful, when you marry, that you have money of your own. And, having money of your own, keep it. Never be dependent on your wife for the occasional little sums which even the most prudent man requires to see him through the day. Take my case. When I married, I was a wealthy man. I had money of my own. Lots of it. I was beloved by all, being generous to a fault. I bought my wife—I am speaking now of my first wife—a pearl necklace that cost fifty thousand dollars.”

He cocked a bright eye at George, and George, feeling that comment was required, said that it did him credit.

“Not credit,” said Mr. Waddington. “Cash. Cold cash. Fifty thousand dollars of it. And what happened? Shortly after I married again I lost all my money through unfortunate speculations on the Stock Exchange and became absolutely dependent on my second wife. And that is why you see me to-day, Winch, a broken man. I will tell you something, Pinch—something no one suspects and something which I have never told anybody else and wouldn’t be telling you now if I didn’t like your face . . . I am not master in my own home.”

“No?”

“No. Not master in my own home. I want to live in the great, glorious West and my second wife insists on remaining in the soul-destroying East. And I’ll tell you something else.” Mr. Waddington paused and scrutinized the fountain-pen with annoyance. “This darned cigar won’t draw,” he said petulantly.

“I think it’s a fountain-pen,” said George.

“A fountain-pen?” Mr. Waddington, shutting one eye, tested this statement and found it correct. “There!” he said, with a certain moody satisfaction. “Isn’t that typical of the East? You ask for cigars and they sell you fountain-pens. No honesty, no sense of fair trade.”

“Miss Waddington was looking very charming at dinner, I thought,” said George, timidly broaching the subject nearest his heart.

“Yes, Pinch,” said Mr. Waddington, resuming his theme, “my wife oppresses me.”

“How wonderfully that bobbed hair suits Miss Waddington.”

“I don’t know if you noticed a pie-faced fellow with an eyeglass and a toothbrush moustache at dinner? That was Lord Hunstanton. He keeps telling me things about etiquette.”

“Very kind of him,” hazarded George.

Mr. Waddington eyed him in a manner that convinced him that he had said the wrong thing.

“What do you mean, kind of him? It’s officious and impertinent. He is a pest,” said Mr. Waddington. “They wouldn’t stand for him in Arizona. They would put hydrophobia skunks in his bed. What does a man need with etiquette? As long as a man is fearless and upstanding and can shoot straight and look the world in the eye, what does it matter if he uses the wrong fork?”

“Exactly.”

“Or wears the wrong sort of hat?”

“I particularly admired the hat which Miss Waddington was wearing when I first saw her,” said George. “It was of some soft material and of a light brown colour and . . .”

“My wife—I am still speaking of my second wife. My first, poor soul, is dead—sticks this Hunstanton guy on to me, and for financial reasons, darn it, I am unable to give him the good sock on the nose to which all my better instincts urge me. And guess what she’s got into her head now.”

“I can’t imagine.”

“She wants Molly to marry the fellow.”

“I should not advise that,” said George seriously. “No, no, I am strongly opposed to that. So many of these Anglo-American marriages turn out unhappily.”

“I am a man of broad sympathies and a very acute sensibility,” began Mr. Waddington, apropos, apparently, of nothing.

“Besides,” said George, “I did not like the man’s looks.”

“What man?”

“Lord Hunstanton.”

“Don’t talk of that guy! He gives me a pain in the neck.”

“Me, too,” said George. “And I was saying . . .”

“Shall I tell you something?” said Mr. Waddington.

“What?”

“My second wife—not my first—wants Molly to marry him. Did you notice him at dinner?”

“I did,” said George patiently. “And I did not like his looks. He looked to me cold and sinister, the sort of man who might break the heart of an impulsive young girl. What Miss Waddington wants, I feel convinced, is a husband who would give up everything for her—a man who would sacrifice his heart’s desire to bring one smile to her face—a man who would worship her, set her in a shrine, make it his only aim in life to bring her sunshine and happiness.”

“My wife,” said Mr. Waddington, “is much too stout.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Much too stout.”

“Miss Waddington, if I may say so, has a singularly beautiful figure.”

“Too much starchy food, and no exercise, that’s the trouble. What my wife needs is a year on a ranch, riding over the prairies in God’s sunshine.”