Cheerio! American Slang Is Far Better Than England’s;

Mr. Wodehouse, Past Master of It in His Stories, Says So

He Awards Palm to This Country for Invention

of Expressive Colloquial Phrases—Says Modern

Girl Is Slangy and Slang Is Human.

By Roger Batchelder.

Flappers, slang slingers, anti-purists, and you, ladies and gentlemen, who occasionally let the tongue slip and say “I’ll tell the world,” or something equally open to criticism when injected in the traditional conversation of the drawing room, cheer up!

No longer need you assume an air of bravado if you don’t care, nor quiver with remorse if you do. For your champion is at hand.

Slang is hot stuff; it is acceptable in the best circles of England and the United States, and according to the present indications the social lion or the feminine “life of the party” will be forced, in the next generation, to be able to use clever, original slang at just the right moment, if he or she is to remain a social leader.

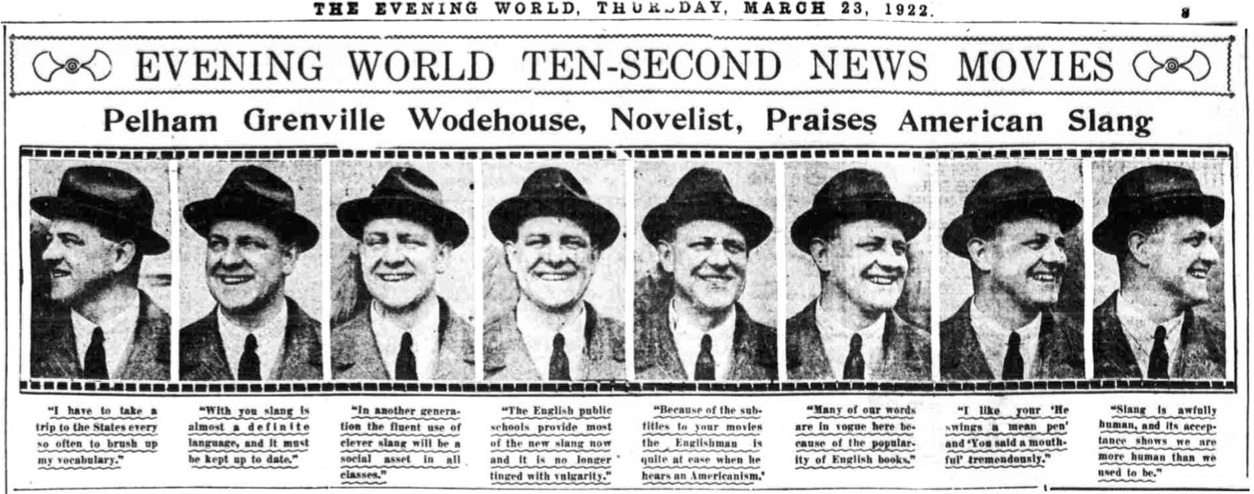

These assurances of the respectability of “the vernacular” come from Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, English writer, who is known to the United States and England as the master of slang. Every page of his books and short stories has a dozen examples; his heroes and heroines say things which, according to the standards of old, they shouldn’t.

“Humor is the basis of all slang,” declared Mr. Wodehouse yesterday in his suite at the Algonquin. “That is why this country excels in the invention of clever words and phrases. America laughs and smiles perpetually, and her colloquial expressions bear witness to that fact.”

“Then you prefer our slang to yours?”

“Absolutely! Right-o! It is much more expressive.”

“For example?” I suggested.

Mr. Wodehouse reached for another of the half-dozen pipes which lay on the table and filled it. Then he thought for a moment.

He is a tall, well-built man and appears to be—shall we say “about thirty-five?” He might be called a “typical Englishman” at first glance, or when one hears his decided accent. But his cordial manner, his enthusiasm when speaking, the sparkle of his eyes as he delights his hearer with a dry, humorous remark, take him from any specific category. “Typically Wodehouse”—that better describes him.

“Take money, for instance,” he said suddenly. “In England we have only ‘dibs,’ ‘splosh’ and ‘o’goblins.’ No one knows where they came from. Here you have a dozen expressive words.”

And he named these: “Dough,” “mazuma,” “roll,” “rocks,” “kale,” “wad,” “cush,” “iron men,” “long green,” “beans,” and “berries.”

“As a matter of fact,” he confided, “I have to take a trip to the States every so often to brush up my vocabulary. If I’m away a long time it gets rusty. In England, you know, slang seems to go on and on. The change from ‘Cheero’ to ‘Cheerio’ was quite an innovation for us. If we had invented ‘I’ll tell the world’ it would have been current for years. But, six months afterward, American inventiveness had brought ‘I’ll inform the universe’ and other variations. With you slang is almost a definite language, and it must be kept up to date.”

“Isn’t it as popular in England?” I asked.

“Our modern girl is very slangy,” he replied, “but if her remarks are clever they are perfectly acceptable anywhere. I presume that in another generation the fluent use of clever slang will be a social asset in all classes. The war has given it respectability.”

“You mean that the words and terms were invented during the war?” I asked.

“To a certain extent. It is particularly true of the Flying Corps, for its members brought back many technical slang phrases which have come into common usage. For instance, there is ‘getting your wind up,’ which means ‘getting rattled.’ The old music halls of London, which are now almost a memory, were formerly the chief sources of colloquial expressions. Heard on the stage one night, they would be all over London the next day. The public schools provide most of the new ones now, and it is interesting to note that they are no longer tinged with vulgarity, but are more dignified and of a higher grade.

“England is adopting many of your terms. Ten years ago, if one of my books was first printed in this country, I had to rewrite it before it would be intelligible to the English reader. To-day, however, principally because of the sub-titles of your movies, and also from the wide circulation of O. Henry and other writers, the Englishman is quite at ease when he hears an Americanism. On the other hand, many of our words are in vogue here because of the popularity of English books and stories.”

Mr. Wodehouse confessed that he had favorites in the vocabulary of slang.

“I like ‘He swings a mean pen,’ and ‘You said a mouthful’ tremendously,” he said. “Our most happy word, I think, is ‘blotto,’ though an Englishman is always at his best in terms of address. If he calls a friend ‘Old bean’ on Monday, it would never do to repeat it on the next day. Tuesday it would be ‘Old egg’ and Wednesday would undoubtedly bring forth ‘Old crumpet.’ ”

Mr. Wodehouse forgot all about the regular interview for a moment and burst forth, “I want to tell you about the race horse Mrs. Wodehouse owns. His name is Front Line, and since we bought him at Hunt Park he has won, carrying 13 stone 3—a record—and came in second last year in the Caesarewitch.”

Then we talked about sports for a time, and I found that the author liked American football, but much preferred Rugby.

“Now to sum up,” I suggested, “what do you think of this ‘slang wave’ which seems to be upon us?”

“There is nothing demoralizing about it,” he said seriously. “Slang is awfully human, and the fact that it is acceptable shows that we are all the more human than we used to be. It is a good sign and a wonderful thing, in my opinion.”

And as I left the room I thought I would try an avowed Anglicism.

“Pip-pip,” I ventured.

“So long,” smiled Mr. Wodehouse.

| WHICH BEST TELLS ITS STORY? ___________________ | |

| ENGLISH VERSION. | AMERICAN EDITION. |

| 1. Right-o. | 1. You said it. |

| 2. Leg it. | 2. Beat it. |

| 3. Slug a slop. | 3. Slam a cop. |

| 4. Toodle-oo or Pip-pip. | 4. So long. |

| 5. Shall we stagger forth? | 5. Shall we run along? |

| 6. Sir Philip had a most ghastly thirst on. | 6. Sir Philip’s tongue was hanging out. |

| 7. I was possibly a little blotto; not whiffled, perhaps, but indisputably blotto. | 7. Possibly I had a small edge on; not really stewed, but a few sheets to the wind, at any rate. |

| 8. That’s a fruity scheme. | 8. That’s a rare idea. |

| 9. I would just hang round in the offing, shoving in an occasional tactful word. | 9. I would just stick around, handing out a happy thought now and then. |

| 10. I’ll slang her in no uncertain voice. | 10. I’ll hand it to her straight from the shoulder. |

From the New York Evening World, March 23, 1922.

Original at Library of Congress.

Note: Thanks to Neil Midkiff for providing the transcription and images for this story.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums