Piccadilly (London), April 27, 1929

IF I have a fault as a writer—a laughable idea, you will say, no doubt, but still the thing is just within the bounds of possibility—it is a tendency to devote myself a little too closely to the subject of butlers. Critics have noticed this butler complex of mine. “Why is it,” they ask, “that Wodehouse writes so much about butlers? There must be some explanation. This great, good man would not do it without some excellent reason.” Well, the fact is, butlers have always fascinated me. Mystery hangs about them like a nimbus. How do they get that way? What do they think about, if anything? Where do they go on their evenings off? And, if you come right down to it, why are they called butlers? If the word is a corruption of bottlers, it is surely a misnomer. A butler does not bottle. He unbottles.

Be that, however, as it may, it has always seemed to me one of the most bitter ironies of life that the intellectual poor, who are endowed with the sensibility necessary for the proper appreciation of butlers and the imagination to enjoy them to the full, should be unable to afford them; while the dull and stupid rich, to whom there is no romance in a butler, are never without them. I know a man who has two, one for day, one for night duty; so that at whatever hour you enter his house there is buttling going on at full blast.

This is all wrong. For, hard as it is to be a good butler, it is still harder to be a good butlee. It is not easy to buttle, but it is still more difficult to be buttled to.

As an instance of what I mean, take the case of some acquaintances of mine in New York who, after cleaning up rather largely in General Motors, awoke one morning in the midst of the enjoyment of their novel wealth, to find that an English butler had imperceptibly insinuated himself into the home. The discovery left them aghast. Some are born to butlers, others achieve butlers, and others have butlers thrust upon them. My friends belonged to the last class. In the daily recriminations which followed Mergleson’s arrival, each of the family denied hotly that he or she had been responsible for his engagement. They came to the conclusion in the end that nobody had engaged him, but that he had just materialised like some noxious vapour given out by their wealth.

At any rate, from the moment of his arrival, happiness took to itself wings. If they had been American song-writers, they would have said that skies were grey and that they had lost the blue bird. Mergleson had been with a Duke, and on the occasions when I dined with these unfortunate people it would have touched a far harder heart than mine to observe the way they cringed before the man. They congealed beneath his cold eye. They quailed at the proximity of his bulging waistcoat. If conversation became for an instant free and unselfconscious, it collapsed at the sound of Mergleson’s quiet, disapproving “Sherry or Hock, Sir?” Sometimes, out of sheer bravado, one of the sons, in the devil-may-care way of youth, would begin a funny story, only to subside half-way through as he heard that short, soft cough behind him—the cough which seemed to say “Pardon me, but this sort of thing would hardly have done for His Grace.”

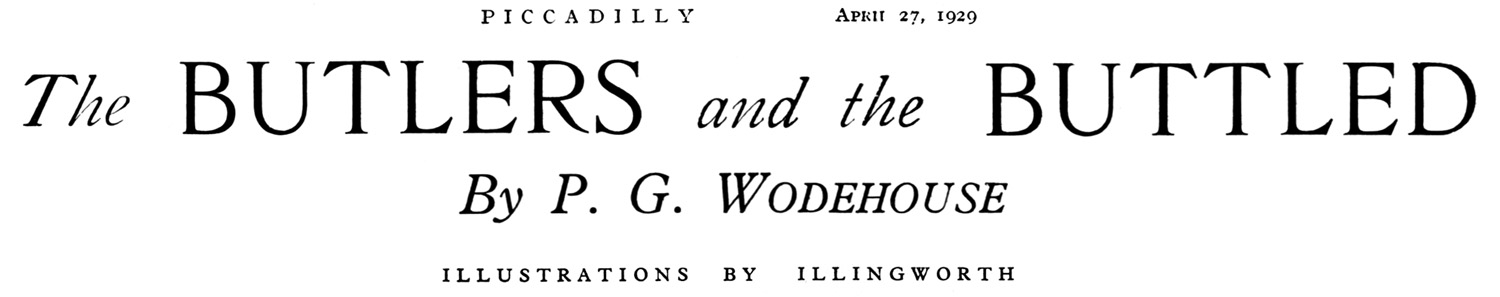

I forget how it all ended. They could not have shot the man, or I should have seen it in the papers. They could not have given him notice, for they had not the courage. I imagine they talked the thing over, and one night, having made sure that he was asleep, they all packed their suit-cases and sneaked away somewhere out West.

I merely mention the affair to prove my point that it is not every man who is capable of being buttled to, and that mere wealth ought not to be permitted to corner the butler market, as it is under the present slipshod conditions of our social life. Over in England, a mere five days’ journey from the house of these wretched creatures, there must have been dozens of men to whom Mergleson would have been a comfort and a boon, but who were barred from employing him by their impecuniosity. Some day, no doubt, there will be a sort of Fund or Institution for supplying the deserving poor with butlers. Public examinations will be held periodically, and those who pass them will receive these prizes quite independently of their means.

One can foreshadow without much difficulty some of the questions which would be put to the candidates. For instance:—

(1) What would you do if you were a guest in a big house and you met the butler unexpectedly on the stairs?

Answer (Adjudged correct by the examiners):—

I should either (a) stare haughtily at the man or (b) say “Ah, Stimson! I am looking for His Grace, Her Grace, His Lordship, Her Ladyship, and Colonel Maltravers-Morgan. Have you seen them anywhere?”

(Adjudged incorrect):—

I should (a) shuffle my feet; (b) faint; (c) hurl myself over the banisters.

(2) Is familiarity with a butler ever permissible?

Answer (Adjudged correct by the examiners):—

Certainly. All butlers are interested in racing and the Stock Market. It is perfectly in order to say to a butler (a) “Oh, Spink, before I forget. Put your dickey on Buttercup for the two o’clock at Ally Pally next Saturday,” or (b) “Very unsettled, the market, this afternoon, Spink—very unsettled.”

(Adjudged incorrect):—

Only in an assumed voice, over the telephone.

(3) What services may a man legitimately demand of a butler?

(Adjudged correct):—

(a) The supplying of light for a cigar; (b) a jerk at the collar of one’s overcoat just as one has got it on; (c) a corroboration of one’s suspicion that the weather is threatening.

(Adjudged incorrect):—

None.

It is one of the compensations of increasing age that fear of butlers (that butler-phobia of which Herbert Spencer and other philosophers have written so searchingly) decreases with the passage of the years and eventually, as the hair grows sparser and the figure more abundant, vanishes altogether. But it may be taken as an axiom that a man under the age of twenty-five who says he is not afraid of butlers is lying. In my own case I was well over thirty before I could convince myself, when paying a social call, that the reason the butler looked at me in that cold and distant way was that it was his normal expression when on duty, and that he did not do it because he suspected that I was overdrawn at the bank, had pressed my trousers under the mattress, and was trying to make last year’s hat do for another season.

It is one of the compensations of increasing age that fear of butlers (that butler-phobia of which Herbert Spencer and other philosophers have written so searchingly) decreases with the passage of the years and eventually, as the hair grows sparser and the figure more abundant, vanishes altogether. But it may be taken as an axiom that a man under the age of twenty-five who says he is not afraid of butlers is lying. In my own case I was well over thirty before I could convince myself, when paying a social call, that the reason the butler looked at me in that cold and distant way was that it was his normal expression when on duty, and that he did not do it because he suspected that I was overdrawn at the bank, had pressed my trousers under the mattress, and was trying to make last year’s hat do for another season.

The sting has passed now, but I freely admit that my nonage, that period of life which should be all joy and optimism, was almost completely soured by the feeling that, while we lunched, the butler was registering silent disapproval of the peculiar shape of the back of my head.

But, then, those were the days when butlers were butlers. You never met one under sixteen stone, and they all had pale, bulging eyes and tight-lipped mouths. They had never done anything but be butlers, if we except the years when they were training on as second footmen. Since then there has been a war, and it has changed the whole situation. The door is now opened to you by a lissom man in the early thirties. He has sparkling, friendly eyes and an athlete’s waist, and when not opening doors he is off playing tennis somewhere. The old majesty which we used to find so oppressive between 1900 and 1910 has given place to a sort of cheery briskness. Formality has disappeared. I know a man whose butler is his old soldier-servant, and his method of receiving the caller is to open the front door about eleven inches, poke his head through and, after surveying the visitor with some suspicion, say in broad Scotch, “Whit d’ye want?” It takes away all that sense of chill and discomfort which one used to feel in one’s early twenties when, in a frock-coat which had not been properly pressed, one encountered the Spinks and Merglesons.

It amuses me when, as sometimes happens, I hear thoughtless people criticising butlers on the absurd ground that they are useless encumbrances for whose existence there is, in these enlightened days, no excuse. There is one unanswerable retort to these carpers—to wit, abolish butlers, and what would become of the drama? You might just as well expect playwrights to get along without stage telephones. To the dramatist, a butler is indispensable. Eliminate him, and who is to enter rooms at critical moments when, if another word were spoken, the play would end immediately? Who is to fill gaps by coming in with the tea-things, telegrams, the evening paper, and cocktails? Who is to explain the plot of the farce at the rise of the curtain?

Dramatists realise this, and of late years it has been rare to find a butler-less play. In a way, this is a pity. In the old days butlers were confined mostly to Society comedies and farces adapted from the French, which made it very convenient for, directly you saw one come on the stage, you were able to say to yourself, “Ah, so this is a Society comedy or a farce adapted from the French, is it?” and steal away to a musical comedy while there was still time to escape.

Butlers are popular in the motion-picture world, but the writers of scenarios appear to have a sketchy idea of what their actual duties are or how they are dressed. Outside a film drama it is rarely that one sees a butler—in Dundreary whiskers and a zebra-striped waistcoat—announce a visitor and stand listening to the ensuing conversation with his elbows at right angles to his body and his chin held rigidly on a level with his forehead.

But, after all, the stage has made equally bad mistakes in its time. It used to be a stage tradition that, if ever misfortune hit the home, the butler came forward and offered his employers his savings to help them over the crisis. In real life butlers are almost unbelievably slow to take their cue on such occasions. A friend of mine was telling me of what happened when he was caught short of Amalgamated Cheeses. His first act was to ring the bell and inform his butler.

“Meadowes,” he said, “I have had very serious losses in the market.” “Indeed, sir?” said the worthy fellow. “I hardly know where to turn for the stuff, in fact,” said my friend. “Yes, sir?” “In fact, Meadowes, I am absolutely ruined.” “Very good, sir.” Finally my friend grew tired of delicate innuendo. “Meadowes,” he said, “if you could see your way to letting me have those savings of yours . . .” Something like emotion animated the man’s mask-like face.

“No, sir, thank you, sir,” he said in a quiet, respectful voice. “Not if I know it, sir. And I should like to give a week’s notice, sir.”

You cannot rely on the drama as a guide when dealing with butlers.

Notes:

An expanded and slightly revised version of “All About Butlers” (1916). Further expanded and revised as “Butlers and the Buttled,” a chapter in Louder and Funnier (1932).

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums