Ladies’ Home Journal, January 1916

WHEN the London society papers announced that No. 8 Grosvenor Square had been rented for the coming season by Mr. J. Macklin Ringwood, the New York millionaire, who was being accompanied on his pilgrimage by his wife Euphemia and his only daughter Marion, the family put it, in varying degrees of bluntness, to the Honorable Algernon Wynbrace that here was his chance. They fed Algernon raw meat and fumbled with his leash. They sicked him on with encouraging cries.

His uncle, Lord Wildersham (pronounced Wing, to rime with Chiddingfold), on whose grudging bounty Algernon was dependent, took him into the library and spoke serious, guarded words.

“This,” said Lord Wildersham, “is a great opportunity for you, Algernon, my boy. Heaven forbid that I should advocate any such thing as a mercenary marriage. Nothing could be farther from my intentions. I merely point out to you that this is an opportunity not rashly to be ignored. Miss Ringwood is a charming girl in every respect, and for that reason alone I recommend you to consider very earnestly the idea of endeavoring to win her esteem and affection. It is time that you settled down.

“In this particular case you would start with every chance in your favor. Mr. Ringwood, a most estimable man, one of those captains of finance of whom America is so justly proud, is a personal friend of mine. He was my host during the fortnight which I spent in the States in the spring of 1907, and my book, ‘America and its People,’ is dedicated to him. I am sure that he would be as delighted as myself if a union—er, just so. Think it over, my boy.”

His aunt, Lady Wildersham, was franker.

“I see the Ringwoods are in town,” she said. “Send Algernon round at once.”

And his aged grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Shropshire, who at the age of eighty-seven still retained unimpaired those keen faculties and that sterling instinct for business which had made her known affectionately to her wide circle of tenants as “the horse-leech,” telegraphed from Drexdale Castle, her country seat:

Ringwoods arrived Grosvenor Square. See Bradstreet. Query, Algernon: Why not?

Without, in short, a dissentient voice the whole family pointed out to Algernon his duty, and stood by to see that he did it.

The Honorable Algernon Wynbrace was at this time in his twenty-fifth year. Nature had bestowed upon him a pleasing countenance and one of those amiable temperaments which yield readily to influence from outside. Indeed, if he had a fault, it was that, when not influenced from outside, he was inclined to drift through life in a state of almost complete inertia. It was a saying with us at Eton that the only way to get Algie to do anything except to eat was to light a fire under him and leave the rest to nature. He was perhaps a trifle inclined to be negative. His only really positive quality was a fondness for musical comedy which at times amounted to an obsession.

HIS negative qualities, however, were numerous and varied. He did not like oysters. He could not “stick” his uncle, Lord Wildersham. He was “frightfully fed” by his aged grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Shropshire. He was “bored pallid” by such widely differing things as Wagner, the future of woman, all literature except the sporting papers, breakfast, problem plays, Cubist painting, and lawn tennis, and the movement for the better housing of the workingman. And he hated cats.

His antipathy for cats, indeed, was so pronounced as to merit inclusion among his positive qualities. It was no mere passing distaste. He was not “frightfully fed” by cats, nor did they bore him pallid. They affected him with a genuine horror. In the presence of a cat he lost that repose which stamps the caste of Vere de Vere and became a sort of gesticulating semaphore. Such an aversion is inexplicable, but by no means rare. Napoleon and the late Lord Roberts, though differing from Algie in many important respects, resembled him in this one particular.

“Can’t stand them, old top,” he confided to me once in a moment of expansion. “Never could. Don’t know why. They just give me the pip, that’s all.”

Algernon, once it had been made clear to him that his family proposed to nag at him without ceasing till he showed signs of being about to get action in the matter of Miss Ringwood, pulled himself together and began the campaign with not a little resolution. He started, as his uncle had predicted, with every chance in his favor. Mr. Ringwood, who was one of those spaciously hospitable men who do not mind what the wind blows in, made him feel at home from the outset. Mrs. Ringwood took to him at once. And Marion, to whom Algernon was something entirely new, welcomed him with that enthusiasm which she always showed toward anything novel. Hers was a vivid, restless mind, demanding constant stimulation: and Algernon, paradoxically, stimulated it simply by being unstimulating.

ALL her life Marion Ringwood had been accustomed to the society of bright, alert, able, ambitious, keen young men; and to meet a human jellyfish like Algernon gave her that then-felt-I-like-some-watcher-of-the-skies-when-a-new-planet-swims-into-his-ken feeling which one so rarely experiences in a prosaic world. To Marion, the Honorable Algie was the Great Mystery. He seemed too tired to breathe, yet he kept alive. It is not too much to say that in the first days of their acquaintance Algie fascinated her.

Theirs was a coming together of opposites. The girl was a good conversationalist, Algie an admirable listener. There is no surer foundation for the happy marriage.

Algie’s wooing proceeded on exactly opposite lines to that of the late Othello. The latter won the heart of Desdemona by speaking of most disastrous chances, of moving accidents by flood and field, of hairbreadth ’scapes i’ the imminent deadly breach, and similar events. Algernon produced almost equal results by sitting in a chair and letting his Desdemona relate her autobiography. When she paused for breath he said: “No, really?” When she seemed to expect some comment he said: “Extraordinary, what?” When she did not pause, but went straight on, he nodded. It was a simple method, and, as involving the minimum of trouble, peculiarly suited to Algie; and it was wonderfully effective.

The campaign was making excellent progress. Lord Wildersham began to lose his worried look. Lady Wildersham addressed her nephew as “Algie dear” twice in a single day. And the Dowager Duchess of Shropshire wrote him a letter which did not contain a single word of abuse—a record.

THE only person who was not pleased was Chester Bellington Bassett, first secretary to the American Embassy. He regarded Algie as a “boob,” an excrescence and a pest, and in the immediate circle of his friends he said so with considerable freedom. For Chester was jealous.

Chester Bellington Bassett was one of those bright, able, alert, ambitious, keen young men to whose society Marion Ringwood had been accustomed all her life. He had been in love with Marion since their first meeting, two years ago, at a ball in Washington. He had looked on her visit to London, whither his diplomatic career had sent him, as the one supreme bit of luck that had ever happened to him. Short of sleeping on the doorstep of No. 8 Grosvenor Square in order to be there when she arrived, he had neglected nothing which would enable him to be first in the field. And now, just when things had seemed to be going so well, along came Algernon.

What she could see in Algie baffled him. He examined Algie with the severely impartial eye of a rival, and dismissed him as a mere chunk of barely sentient matter cumbering the ground and poisoning the surrounding atmosphere. It astounded him that a sensible girl could entertain toward Lord Wildersham’s nephew any feeling warmer and more cordial than a desire to duck down a side street when she saw him coming. Yet there she was, prattling away to this scarcely animate blob of imbecility as if he were the only thing on earth. Chester felt embittered.

BUT he did not despair. There were times when he felt that it was useless to continue, that he was simply “among those present” and had no chance at all; but the dogged courage of the Boston Bassetts sustained him and he continued to do his best. His best took the form for the most part of sending Marion things by special messenger. As the Etiquette Book so well puts it, “When a young man’s fancy develops from mere liking for a charming girl into serious thoughts of matrimony, his first and most natural impulse is to bestow gifts upon the object of his admiration.” That was Chester in a nutshell. At this period of his career he was probably the most prominent gift-bestower on the eastern side of the Atlantic Ocean. When he was not making his presence felt among the chancelleries, or whatever it is that first secretaries to embassies draw their weekly pay-envelopes for, he was sending Marion gifts. He showed no discrimination. He just gave her anything that came within his reach. By the end of the first month she was in receipt of possibly a ton of assorted flowers, a hundredweight or so of candy, two canaries, the complete works of Marie Corelli, a fan, a fountain pen, a parrot, eleven talking-machine records and a Japanese spaniel.

None of these things, however, affected the general situation. The first event of military importance occurred when he added a Persian cat to the long roll of junk which he had unloaded on No. 8 Grosvenor Square.

It was Algie’s fault that Chester ever came within five miles of the cat. If he could have conquered his fatal weakness to the extent of escorting Miss Ringwood to the Crystal Palace cat show, his rival would never have learned of Alexander’s existence—for such was the name of the animal. But he absolutely declined to escort Miss Ringwood to the show, pleading several previous engagements, and she thereupon enrolled Chester Bassett as a substitute.

IT STRUCK Chester Bassett as one more instance of the unkindness of fate that the particular cat on which Marion had set her heart was not for sale. All the afternoon they cruised together through an ocean of cats—big cats, small cats, black cats, white cats, gray cats, yellow cats, brown cats, and particolored cats; but none appealed to Miss Ringwood except this Persian cat, Alexander, the property of a Miss Matilda Robinson. And Miss Robinson, who sat beside her pet’s couch like a guardian angel, firmly declined to negotiate. She looked on Alexander as a son.

Time passed. Algie continued to make progress. It seemed as if everything was over except the wedding announcements. Lord Wildersham had become positively radiant. Lady Wildersham’s beaming smile was now a byword in the best circles. The Dowager Duchess of Shropshire sent Algie a pot of homemade jam.

And then, one afternoon, as Algie sat in his favorite attitude in one of the drawing-room chairs at No. 8 Grosvenor Square, listening to Miss Ringwood’s description of how she had lost a suitcase while traveling from Rome to Paris, a narrative of the deepest interest, the door opened and Chester Bassett was announced.

To Algie, resting on his spine in the drawing-room chair, it seemed that there was something in Chester’s manner which he did not quite like, a sort of suppressed elation. There was something about Chester which made him feel uneasy. “Right from the start,” he confided to me later at the club, “I had a kind of what-d’you-call-it. A sort of thingummy, don’t you know, what?”

Chester Bassett opened fire without delay. “I have good news for you, Miss Ringwood. You remember that cat we saw at the Crystal Palace? I was out to dinner last night, and I sat next to Miss Robinson. You recollect Miss Robinson? She has changed her mind about Alexander.”

“Oh, Mr. Bassett, how splendid! Will she sell him?”

“She has sold him. I took the liberty of buying him as a present for you, as you took such a fancy to him.”

“How perfectly divine! I can’t tell you how grateful I am, Mr. Bassett. I fell in love with Alexander the moment I saw him. But how strange that she should have been willing to part with him! She was so very determined that afternoon. She said she looked on him as a son.”

A SLIGHT embarrassment betrayed itself in Chester Bassett’s manner. “That,” he explained, “is what you might call the crux of the matter. She looked on him as a son, and he double-crossed her. It seems that the day before yesterday he had the misfortune to present to her six fine kittens, and there is now a certain coolness between them. However, out of evil cometh good, and I have been able to get him—her, I mean—for you. He—she—it is downstairs in a basket.”

The next moment Marion had rung the bell, and shortly afterward the basket appeared, and before Algie’s revolted eyes the cat was decanted on the drawing-room floor.

If you have ever seen a pugilist, happily conscious that he has successfully outpointed his antagonist, come up for the last round of a fight, a soft smile playing about his lips as he dips into the future and sees himself spending the winner’s end of the purse, and suddenly receive a crushing blow just above the waistline, you will have a rough idea of Algie’s emotions as he watched Alexander emerge from his basket. It was not only the discomfort which the cat’s presence caused him at the moment, though that was considerable. What paralyzed him was the thought of what was to come.

From that moment Algernon, from being a hundred-to-one shot in the Ringwood stakes, receded to one to a hundred and no takers. It has been explained that his greatest charm in Marion’s eyes was his supreme restfulness, his air of almost entirely suspended animation. The arrival of Alexander robbed him of this. In Alexander’s presence—and he was always present—Algie fidgeted, wriggled in his chair, forgot to say “Extraordinary, what?” when given his cue, and altogether behaved in a manner which caused Miss Ringwood to regard him first with surprise, then with resentment, and finally with indifference, and to direct the searchlight of her smile exclusively upon Chester Bellington Bassett.

Even to Algie’s limited intelligence it became apparent that something must be done. The home authorities were becoming restless. Lord Wildersham demanded action. Lady Wildersham quoted the proverb about faint heart and fair lady three times one evening at dinner between the soup and the savory. The Dowager Duchess of Shropshire threatened to come to London and give Algie a piece of her mind.

It was probably this last threat that spurred Algie to act. His imagination recoiled from the thought of his aged grandmother’s going about the metropolis giving him pieces of her mind. She had done it on previous occasions, and it had made him feel quite faint.

So Algie acted.

THE intelligent reader will remember, though the vapid and irreflective reader (that worm) will have forgotten, that one of the gifts which Chester Bellington Bassett had bestowed upon Marion Ringwood was a parrot. He had bought it for her because, one afternoon when they were slumming or doing Dickens’ London or something—at any rate, they were wandering together through Soho—she had caught sight of it in a window and coveted it. It had cost Chester Bassett ten dollars, a long and maddening argument with an unintelligent alien who mistook him for a detective and denied everything that was said to him, and an inch of flesh out of his finger, to get the bird to No. 8 Grosvenor Square; but he had done it eventually, and the parrot now lived in the hall of that stately home of England, a great favorite with Miss Ringwood and her father.

One afternoon Algie found himself alone in the hall. He was spending a few days at No. 8 as the guest of Mr. Ringwood at the time, his uncle and aunt having left London for their annual visit to Drexdale Castle. Mr. Ringwood, always hospitable, and gathering after half an hour of the broadest hints from his old friend, Lord Wildersham, that the invitation would be acceptable, had invited Algie to move over. The arrangement had the advantage for the latter that he now saw more of Marion, and the counterbalancing disadvantage that he also saw more of Alexander.

He was brooding on Alexander as he entered the hall, when a low voice from the shadows urged him to get his hair cut. Turning, he perceived the parrot, affably regarding him with its head on one side, evidently ready for a heart-to-heart talk. Algie was approaching the cage when he perceived the cat Alexander in the hall.

HIS first impulse was to give his refined imitation of a semaphore, and he had just raised his arms when possibly the first idea he had ever had in his life flashed through what, in relating the affair subsequently, he described as his brain.

“It was a corking good idea, old top,” he told me, “and I don’t know how I ever came to get it. The bally cat, you understand, was advancing in close formation and looking up at the cage in a kind of eager way. Now I knew that Miss Ringwood thought a lot of that bird and would be frightfully fed if anything happened to it, so I just opened the cage door and out the old bird hopped. You get the idea? The program was that the bally cat would manhandle the bally bird, and when Miss Ringwood, who was out at the moment, came back and saw the remains, she wouldn’t stick it and the cat would hit the pavement on one ear and never appear in the house again. What?”

I am usually a sympathetic listener when Algie relates his troubles, but as he set forth this fiendish plot I suppose my manner must have lost some of its sympathy, for he eyed me disappointedly.

“You don’t think a lot of the idea, what?” he said.

“It’s no business of mine,” I replied; “but don’t you think yourself it was playing it rather low down? Wasn’t it a trifle rough on the bird?”

“Yes, I thought of all that, but it was what they call a military necessity, don’t you know? Besides, I didn’t dictate the bird’s movements. He was a what-d’you-call-it?—a free agent. If he wanted to hop out just because I opened the cage door, that was his affair. Besides, as a matter of fact, he didn’t get hurt. Let me tell you.” And he related the incident.

Algie, it seems, wasted no time. Miss Ringwood, he knew, was out. So was Mr. Ringwood. Mrs. Ringwood was in her bedroom, nursing a headache. The chances were against interruption from any of the servants. The coast, in a word, was clear. Algie opened the door of the cage, and retired to the background to give the principals full play.

There was a moment of keen suspense, and then the parrot hopped out. He paused in thought for a while on the back of a chair and then fluttered to the floor. Alexander, the cat, was in immediate attendance. As far as one can judge, Alexander must have thought that he was on to a good thing. His extremely sketchy grasp of the principles of ornithology had long since caused him to classify the parrot as a chicken. It was true that there was a difference in color, and that this bird’s nose was a trifle more Roman than that of any chicken he had hitherto encountered; but these were small matters. Broadly speaking, this was a chicken, and dealing with chickens was one of the things which Alexander did best.

He began to get ready to throw himself into this affair with spirit. Flattening himself on the floor till his chin touched it, he rippled the muscles of his back and switched his tail softly to and fro. This was his way of limbering up. In another instant he would have sprung, but, just as he was about to do so, his intended victim, stepping forward, nodded patronizingly at him and asked him the time.

ALEXANDER executed a backward leap of seven feet and rose in the air like a rocketing pheasant. When the movement was concluded he was on top of the hatstand. From this elevation he surveyed the surprising fowl beneath him with pain and astonishment.

The parrot, dismissing the affair from his mind, began to patrol the floor. Once he looked up, gazed at Alexander with a mild curiosity, recommended to him that haircut which he seemed to regard as the panacea for all ills, human and feline, and resumed his rambles. From his aerie Alexander watched him with saucer eyes and moaned a little. His nervous system was still vibrating from the shock of being asked the time by one he had always looked on as a bird.

It was manifest to Algie, as he surveyed the proceedings, that the only scheme that he had ever thought out in his life had gone agley. He was, as he phrased it to me, “stymied”: “Absolutely stymied, old top.”

But the greatest general is he who can snatch victory from the jaws of apparent defeat, and it must be admitted that in this crisis Algie showed certain of the qualities which make for success on the stricken field—notably a resource of which no one would have suspected him capable, and a dash and agility which would have seemed incredible to those who knew him only as one who loved to nestle on his spine in deep armchairs.

Anyone who had chanced to pass through the hall of No. 8 Grosvenor Square at that moment would have seen a remarkable sight—the spectacle of Algie running upstairs. His usual mode of progression, when he could not secure a taxicab, was a languid walk. On this occasion, however, reckless of possible injury to the crease of his trousers, he raced up the stairs and bounded into his bedroom like a highly trained professional acrobat.

Arrived there, he snatched up a hatbox and bounded back to the hall.

The situation, when he reached the hall, was, as the newspapers say, “unchanged.” The parrot, meditatively crooning expletives, was trying to climb up the box in which the automobile rugs were kept. Alexander, invisible except for two eyes and the tip of his nose, was continuing his policy of watchful waiting.

Algie made for Alexander. He had thought the whole thing out, and had realized that this was the chance of a lifetime. In his normal state of mind Alexander was not so much a solid as a fluid; he could slip through hands, no matter how firmly they gripped. Eels were adhesive compared with Alexander when in full possession of his faculties. But now, as he watched the parrot, he was in a kind of trance.

He did not seem to be aware of Algie’s approach. All his attention was concentrated on the parrot. Before he could rally to cope with the new attack Algie had gripped him firmly, inserted him in the hatbox and slammed the lid.

Algie sped from the house and hailed a taxi-cab, directing the driver to stop at the nearest messenger-boy office.

COMMOTION reigned at No. 8 Grosvenor Square. When Algie returned he found himself in a whirl of people who wandered up and down stairs, making chirruping noises. The butler was poking beneath the furniture with an umbrella. All was confusion and agitation.

In the drawing-room Algie found Miss Ringwood. She was distressed. “Oh, Mr. Wynbrace,” she said, “we can’t find Alexander anywhere. He has disappeared. What can have become of him?”

Algie adjusted his spine till it touched the softest spot of his favorite armchair. “Extraordinary, what?” he said. He had not spoken the words with such confidence and vim since that black day when Alexander had first entered the house.

Miss Ringwood talked to him about Alexander for three-quarters of an hour. She was charmed and soothed by Algie’s motionless attention. She wondered how she could ever have got the impression that he was fidgety.

Chester Bassett was announced. His stock slumped fifty-six points in ten minutes. He struck entirely the wrong note. Where Algie was silent, restful, soothing, Chester Bassett was bright, able, alert, keen. He exuded theories at every pore. He tramped about the room. He irritated Marion extremely. “Leave it to me, Miss Ringwood,” were his last words. “I will manage this.”

And he went off, fizzing with energy.

“He didn’t make one sensible suggestion,” said Miss Ringwood fretfully.

Algie nodded peacefully. “Extraordinary,” he said. “What?”

Marion looked at him tenderly.

The following day found Algie in sole possession of the field. It was late afternoon, and Chester Bassett had not put in an appearance. Either it was a busy day at the chancelleries or, having failed utterly to trace the missing cat, he was ashamed to come back. Algie settled himself in an armchair and ate tea cake. Marion Ringwood talked about Alexander.

IT WAS Algie’s intention that afternoon to put his fortune to the test, to win or lose it all. He had thought of rather a neat way of opening the subject. He was going to wait till Miss Ringwood paused for breath, then he was going to say: “I say, you know, Marion—may I call you Marion?—couldn’t I be a sort of jolly old substitute? What I mean is, take Alexander’s place in your heart, and all that sort of thing, don’t you know, what?” And after that it ought to be simple.

The only trouble was that Miss Ringwood did not pause for breath. She was one of those girls who talk quite independently of whether there is any air in their lungs—solely by will power. She was still going strong when Chester Bassett came in.

As on a previous occasion, there was something about Chester Bassett’s manner which Algie did not like. This time, however, it was not suppressed elation which showed itself in Chester’s deportment. He was openly triumphant. “It’s all right, Miss Ringwood,” he cried. “I’ve got him!”

“Got him!” exclaimed Marion.

“Got him!” muttered Algie, gaping.

“Yes, got him,” repeated Chester Bassett. “Alexander, I mean, of course. At least, I haven’t absolutely got him here, but I know where he is.”

“Oh, Mr. Bassett!” cried Marion. “You’re wonderful!”

“Yes. I mean no, no,” said Chester. “It’s this way. I’ll tell you how I did it. I sat up all night thinking about it, and this afternoon it came to me. I asked myself where a lost cat would be most likely to be in London, and it struck me that the odds were that it was at the Cats’ House in Battersea. So I raced off to the Cats’ House, and there’s a cat there that’s either Alexander or his twin brother.”

“But where is he? Why didn’t you bring him with you?”

“That’s the odd thing. There seems to be some hitch, some sort of red tape. I tried to buy this cat, and the man there said that he must have time to consider. But, of course, if you stop in there and claim him as your cat, they must give him up. I guess that’s the trouble. They wouldn’t sell him to me till the real owner had time to put in a claim.”

“Why, of course,” said Miss Ringwood. “That must be it. If the cat is really Alexander they must let me have him. We’ll all go to the Cats’ House. If we all three identify him, there won’t be any difficulty.”

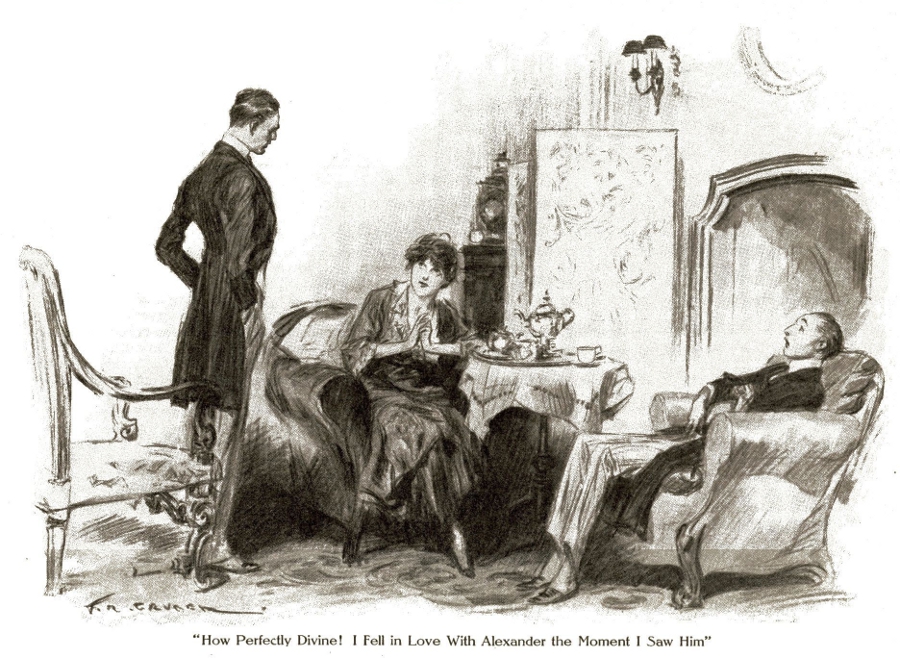

THE manager of the Cats’ House was courteous and obliging. “Of course, if you identify him as your cat, miss,” he said, “the matter is ended. My hesitation when you, sir, approached me this afternoon on the matter was due to the fact that this animal came to us in a curious way. A messenger boy came, asking us to destroy him at once.”

“Why did the messenger boy want to be destroyed?” asked Chester Bassett. “Was he tired of life? Unhappy love affair perhaps?”

“Not the messenger boy,” corrected the manager. “You misunderstood me. It was the cat which was to be destroyed, as per instructions of the anonymous sender. Our delay in carrying out the esteemed order was due to the fact that we make a small charge for destroying cats, and the gentleman had omitted to accompany his request with a remittance.”

Miss Ringwood’s eyes were blazing. She looked at her two companions indignantly, softening only momentarily on seeing that Algie’s sympathy had made him look quite haggard. “Who could have played such a wicked trick?” she cried.

The manager produced a hatbox. “This is what the animal came in. There was no accompanying letter.”

“Maybe there’s a name on the box somewhere,” suggested Chester Bassett. “There usually is on hatboxes.”

The manager turned the hatbox in his hands. “Why, bless me!” he said. “You’re quite right, sir. So there is. Funny of me not to have thought of looking before. Name of Algernon Wynbrace, sir.”

WHEN Algie, telling me the story, reached this point he stopped abruptly and passed a handkerchief over his forehead. “Sorry, old top,” he murmured, “I can’t go into details.”

“She chucked you?” In moments of emotion the simplest language is the best.

He nodded.

“And I suppose she’s going to marry Chester Bassett?”

“Engagement was announced yesterday.”

“And how have the family taken it? I suppose your uncle was disappointed?”

Algie winced. “Disappointed isn’t just the word, old top. Not strong enough. And my aunt was worse than he was. And my grandmother——” He was silent for a while. “They’ve put their foot—feet down, old man. I’ve got to go to work. My uncle’s got me a job as secretary to some blighter, a man called—what’s his name?—got it down somewhere.” He consulted the back of an envelope. “Oh, yes; Wilberforce. He’s a professor or something. Does a lot of writing.”

“You don’t mean Professor Snyder Wilberforce?”

“That’s the man. He’s writing a great work of some kind, so I gathered, and he wants a chap to go to the British Museum for him every day, and hunt up records, and get facts, and so on. All that sort of bally rot, you know. As far as I can gather, it ought to pan out a pretty steady job. He’s been working on this book two years, and expects to be another ten before it’s finished. Wish I knew what it was about. It must be hot stuff.”

“I know what it’s about, Algie. Professor Wilberforce is rather a celebrity.”

“Never heard of him in my life. What is it about?”

“It’s a ‘History of the Cat in Ancient Egypt,’ ” I said.

Note:

For the earlier, much different version of this story, and a note on Lord Roberts, see “The Man Who Disliked Cats” from the Strand magazine.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums