Van Norden, July 1909

WHAT DO THEY ALL DO?

An English Writer’s Impressions and Queries After Witnessing

New York “Rush-Hour”—Asks What These

Casual, Careless Millions Do

By P. G. WODEHOUSE

Foreword.—Who, coming into any great city for the first time, or who, after a long absence from the turmoil of a metropolis, has not asked himself the question, “What do they all do—these hurrying millions?” Who has not been impressed with the extraordinary activity of the city that throngs during the hours in which the people go to or hasten away from work?—Editor.

Jam them in, ram them in,

People still a-coming,

Slam them in, cram them in,

Keep the thing a-humming!

Millionaires and carpenters,

Office boys, stenographers,

Workingmen and fakirs,

Doctors, undertakers,

Brokers and musicians,

Writers, politicians,

Clergymen and plumbers,

Entry clerks and drummers,

Pack them in, whack them in,

People still a-coming!

From Grenville Kleiser’s “Humorous Hits.”

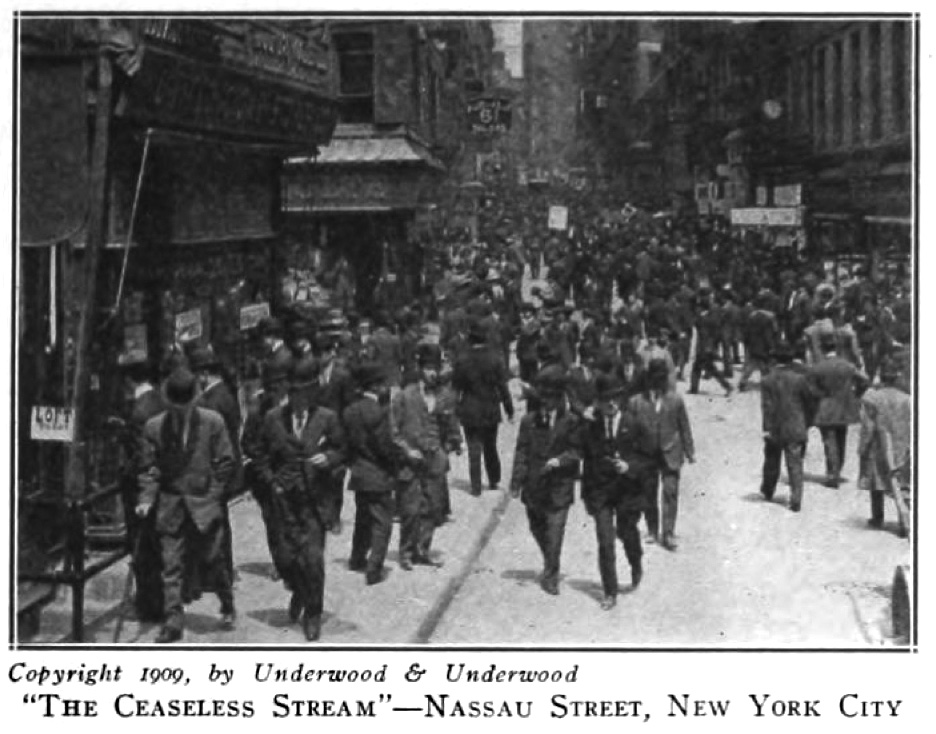

WHEN the giant in Mr. H. G. Wells’ “Food of the Gods” came to London and saw the crowds hurrying to and fro in the streets, he asked, “What’s it all for?” He might have said, “What do they all do?” That is the mystery of every great city. What do these hurrying millions do? How are they employed? How can any city, however vast, find work for them all?

The thought occurs to every stranger in every large city, but it is in New York that the problem is most vivid. There is no rush-hour in London as there is in New York. In London there are times during the day when the Tube, the suburban trains, and the omnibuses are always full, but there is no solid avalanche of humanity such as is to be seen every day at Brooklyn Bridge and the Subway stations at Fourteenth Street, the Grand Central station, and one or two other points.

London stops work gradually. New York stops with a jerk.

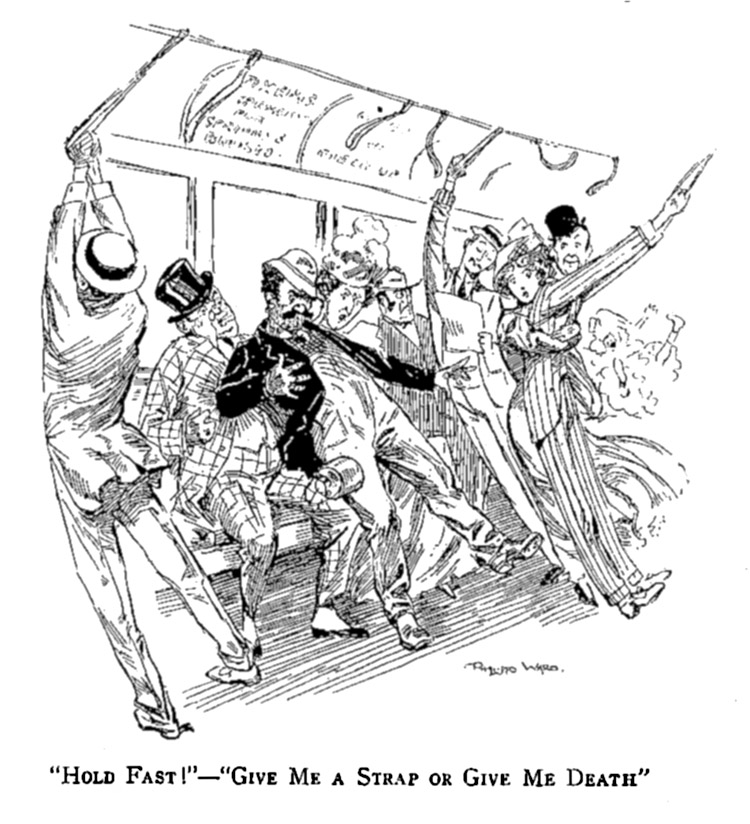

Standing on the corner of East Fourteenth Street at almost any time between five and six in the evening, you will see an endless stream of men and women moving swiftly towards you. It means the workers of New York are bound for home. Every unit in that stream is going up or down town, and is impatient of a second’s delay. It is a race, with seats in the uptown express as prizes for the swiftest, straps for the runners-up, and the privilege of being crushed and trodden on in the rear of the car as a sort of consolation prize for the last to arrive. To the casual spectator there does not seem a great deal to choose between the three modes of traveling. But possibly the man who secures a seat feels a certain glow of honest pride, as the victor in an athletic contest.

Along the subway platform runs a stout iron rail. At intervals along the rail, on the further side, are stationed policemen and guards. The crowd surges on to the platform, pressing against the rail. Presently the policemen step forward and throw back a few feet of the rail. Like water breaking a dam, the crowd pours through the opening. Meanwhile the passengers leaving the train are pouring though another opening a yard or so lower down. And this may be said to be the beginning of the game.

It is a game which at first sight appears to be played without rules. A sort of Titanic shove-as-shove-can. Men and women jostle each other indiscriminately. There is a total absence of irritation and ill-feeling. The seat-seeker feels no more annoyance with the rival through whose body he is apparently trying to push a hole than does the pioneer with the tough piece of undergrowth which he is cutting away. Both are obstructions and must be removed, but there is no animus. A sharp elbow in the ribs is painful, but it is the fortune of war. To receive the full weight of a fellow-struggler on one’s foot is unpleasant, but not to be resented. Perfect good humor prevails.

But the game has its rules, despite appearances. The seats are all occupied now, and one man, determined at least to secure a strap, ignores Subway etiquette and endeavors to pass in through the lower opening, sacred to those going out. The move succeeds. He makes the perilous passage. But Nemesis is waiting on the other side. The tall, blue-clad policeman, his face calm, and wearing a look of abstract speculation, his jaws moving rhythmically as he chews his gum, steps to meet him, seizes him by the shoulders, and forces him back. He is not annoyed, but duty is duty. The trespasser, passionately obsessed with his dream of securing a strap, tries again. This time Nemesis loses a little of his abstracted air, infuses a little personal feeling into the matter. The trespasser, scientifically gripped, is whirled out of the forbidden area, as if he had been shot from a gun. His hat falls off and is trodden on. He retires from the contest. Next time he will play fair.

By now the vanguard of the in-going crowd has filled the

cars, and the uninitiated would say that the train was ready for its journey.

No, the packing process has only just begun. Up to this point it has been left

to the amateur. So far the crowd has packed itself. It is here that the expert

begins to display his skill. The policemen take an active hand in the packing.

The guards all along the train are working strenuously. “Pile ’em on, Willie,”

cries one earnest laborer. And Willie piles. So do Sam and Jim, not to mention

Ted and Jack and Michael. All down the platform men and women are being wedged

into the apparently solid mass of humanity on the cars. There always seems room

for one more. “Pile ’em on, Willie!”

By now the vanguard of the in-going crowd has filled the

cars, and the uninitiated would say that the train was ready for its journey.

No, the packing process has only just begun. Up to this point it has been left

to the amateur. So far the crowd has packed itself. It is here that the expert

begins to display his skill. The policemen take an active hand in the packing.

The guards all along the train are working strenuously. “Pile ’em on, Willie,”

cries one earnest laborer. And Willie piles. So do Sam and Jim, not to mention

Ted and Jack and Michael. All down the platform men and women are being wedged

into the apparently solid mass of humanity on the cars. There always seems room

for one more. “Pile ’em on, Willie!”

At last even the guards are satisfied. With one final effort they pull to the gates. A shout to the conductor, and the train moves off.

And unless the eye deceives, the crowd left on the platform is just as dense as it was before a soul entered that human sardine box.

What do they all do? Where do they all find work? Are there enough offices in the world to provide employment for this vast mass of men and women?

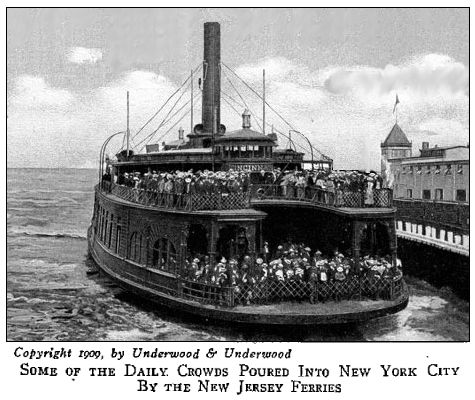

Vast mass? They are only a section of New York’s workers. These are merely the dwellers uptown. What of the rush-hour at Brooklyn Bridge, at the South Ferry, on the elevated? It is a wonderful sight to see the never-ending mass of men and women winding its way like a black serpent through Park Row during the rush-hour and streaming over the Brooklyn Bridge. It is a quieter, more leisurely crowd, this, than that of the Subway. In its day it was active enough, but recent additions to Brooklyn rapid transit have relieved the pressure. As a spectacle it is impressive still, but it lacks the militant character which makes the Subway crowd unique. There is more room. There are more outlets. It is not a question of “Give me a strap or give me death.”

But, as a crowd, as a parade, it is perhaps even more

striking than the gathering in the Subway. Where do they all come from? Who can

possibly employ this almost countless throng? How did they come to select their

various jobs in life? What do they all do?

But, as a crowd, as a parade, it is perhaps even more

striking than the gathering in the Subway. Where do they all come from? Who can

possibly employ this almost countless throng? How did they come to select their

various jobs in life? What do they all do?

Into the offices of a popular magazine, for instance, there come from day to day men and women with unique stories of fact and adventure from all quarters of the globe. In walks an ex-Chief of Police from the Congo, an American Consul from Zanzibar, home on vacation; an adventurer who has been buying furs from the Siberian natives at a price which, he is prepared to demonstrate, maybe, shall make the New York customer turn pale with a desire to possess; a surveyor from the Northwest of Australia, or from New Guinea, with tales of mining camps and lumber areas where even as yet the white man does not dwell—all men with of note in their particular sphere; men who do big things in a big but undemonstrative way. These are among the many with whom we bump elbows on the pavement, and who from the wilds of undeveloped lands enter momentarily and casually into the great struggle of the New York Subway or the Brooklyn Elevated. Is it not true that we know not whom we pass in the street or by whom we stand on ferryboat or platform? Some unknown Milton, mayhap, some undiscovered genius in one sphere or another.

One thing the visitor from abroad is ready to say all New

Yorkers, if not all Americans, do; and that is they put up with more

inconveniences in everyday life than any other people in the world. Jump onto a

trolley bus, and before you have gone ten blocks, the driver will have done his

best to jerk the very life out of you. The same on the Elevated and on the

Subway. I asked a German engineer the other day how he accounted for this, and

he asserted very positively that it was the unfortunate habit of most of the

big traction companies to put men in charge of electrically-driven cars before

they (the drivers) were properly trained; that is, the drivers here are

recognized as efficient on reaching a standard of knowledge which in Europe

would not be considered efficient.  There must be something in that, because

one of the first things to be remarked by an American when he goes to Europe

for the first time, is that in London, Paris and Berlin, especially, he does

not have to hold on to straps and door handles to keep himself at the proper

perpendicular, or if he be seated, does not have to sway his body in order to

cope with the jerks and starts of shockingly-driven conveyances.

There must be something in that, because

one of the first things to be remarked by an American when he goes to Europe

for the first time, is that in London, Paris and Berlin, especially, he does

not have to hold on to straps and door handles to keep himself at the proper

perpendicular, or if he be seated, does not have to sway his body in order to

cope with the jerks and starts of shockingly-driven conveyances.

Truly, these New Yorkers are a long-suffering and good-natured crowd. They bump you in the street as they negotiate even the broadest pavements, but they expect to be bumped in return, and they move on. How is it, however, that so many of them are to be found in the streets at all times of the day and night, when most of us believe that ordinary office hours keep the average employee within doors for the greater part of his or her time? Be sure it is not difficult to find a crowd at any time during the night if there is “anything doing” in New York. Mr. Bryan, during his last campaign, addressed a meeting in City Hall Park at three o’clock in the morning, and there was just as big a crowd attending the meeting then as there had been at any daytime gathering at the same place and they were just as enthusiastic. Where do they all come from? What do they do?

The magazine slightly misquoted Kleiser’s “Song of the ‘L’ ” from Humorous Hits, misplacing some punctuation and omitting one “and”. The quotation above has been edited to match the original poem.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums