The Pall Mall Magazine, February 1914

HE Medical Congress has come and gone, and not

a word has been said about the deadliest scourge that has ravaged England since

the Black Death—the abominable dramatizitis, which takes its toll from nearly

every household in the kingdom. Walk into any home you please, and you will

find at least one victim tossing restlessly in the delirium of farce (the

mildest form of the malady) or even exhibiting well-marked symptoms of the

ghastly Thoughtful Modern Drama (morbus Galsworthiensis). I have even

known cases where the disease assumed epidemic proportions, no fewer than three

victims in a single family being down at the same time with acute light comedy.

HE Medical Congress has come and gone, and not

a word has been said about the deadliest scourge that has ravaged England since

the Black Death—the abominable dramatizitis, which takes its toll from nearly

every household in the kingdom. Walk into any home you please, and you will

find at least one victim tossing restlessly in the delirium of farce (the

mildest form of the malady) or even exhibiting well-marked symptoms of the

ghastly Thoughtful Modern Drama (morbus Galsworthiensis). I have even

known cases where the disease assumed epidemic proportions, no fewer than three

victims in a single family being down at the same time with acute light comedy.

Can nothing be done?

In America matters are even worse. Statisticians estimate that there is not a single adult of either sex in New York, Chicago, Boston, St. Louis, or San Francisco, who has not written or is not writing at least one play. There is something in the air of the United States which seems to encourage the virus. Quite unlikely people—lawyers, baseball-pitchers, stenographers, policemen, and proprietors of delicatessen shops, sicken and go under.

Can nothing be done?

Very little, I fear. There is only one cure for the disease. The sufferer must be operated upon. This is technically known as “production”; and even this is not always successful. There have been cases where patients, after six or more operations, having been discharged as cured, have gone straight off, snatched up a fountain pen and a piece of paper, and started writing “Act One: Scene, a luxuriously-appointed bachelor sitting-room. Door l., door l.c., door c., door r.c., door r., other doors at back, half hidden by hangings. Enter Spink, a valet.” It is enough to make the stoutest-hearted surgeon despair.

In my own case it began in the year 1907 with a comparatively mild attack of musical-comedy lyrics.

From a very early age I have had a marked congenital tendency towards light verse. In the light of later happenings it would have been well if my parents had had this treated; but it seemed so slight and unimportant a failing that it was regarded more with amusement than apprehension. I cannot blame them. Medical science was less advanced then than it is to-day, and the fact that light verse for magazines and daily papers, in itself so harmless as hardly to be counted a disease at all, is the almost inevitable preliminary stage to Lyrics, was not then general knowledge. The consequence was that at the beginning of the year 1907 I found myself, before I realised what had happened, attached to the staff of the Aldwych Theatre as a sort of Hey, Bill! who was expected to turn out topical encore verses every week in exchange for two pounds per and the run of the theatre.

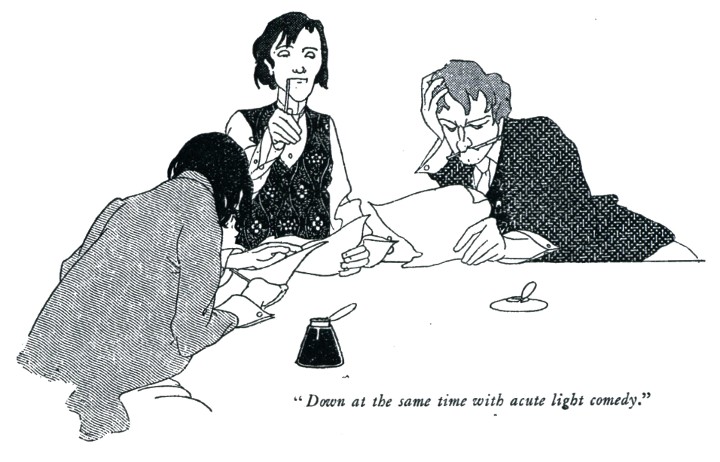

It was this last privilege which had such terrible results. By degrees I acquired a taste for standing in the wings with six separate draughts playing on my person and being bumped into by perspiring scene-shifters. Long before the management sacked me for idleness and incompetence, dramatizitis had hold of my system, and I was feverishly anxious to write part of the book of a musical comedy. The idea of seeing posters bearing the legend:

THE BELLE OF LONDON

(a musical comedy in two acts)

By

John Jones, Robert Smith, Charles Robinson, Edward Jenks, Percival Simpson, and P. G. Wodehouse

Lyrics by

Sidney Binks. Arthur Tompkins, Herbert J. Scott, Stanley Mudd, Alexander Price, and Spencer Delahay

Additional Lyrics by

Theodore Popjoy, Alaric Murgatroyd, and Francis Poole

Extra Scenes by

B. J. Blore, C. D. Eckstein, and Robert E. Lee

Music by

Wagner K. Strauss and Sebastian Rubens

—simply inflamed me. It was not the money I wanted so much as the fame.

I proceeded to collaborate with a similarly afflicted person in a perfectly drivelling comic opera.

It took two months of incessant work to write this masterpiece, and at the moment of going to press it is still unplaced. The assets for my First Play were nil.

It

is possible that this experience would have cured me, had it not been that at

the very instant when I had finally abandoned play-writing I was engaged by the

Gaiety Theatre management. It was the same old Hey, Bill! business, but varied

this time by the fact that one had to climb up to the roof to get one’s weekly

stipend. Here, in a little room, sat a genial gentleman with a tableful of gold

in front of him. The sight of this wealth, though I only diminished it by two o’goblins

per week, so excited me that by the time the management hurled me into the

street for dilatoriness and inefficiency I was once more in the full grip of

the old malady. A commission to write a scene into “The Dollar Princess” (price

fifteen pounds) reduced me to a condition when only an operation could possibly

cure me.

It

is possible that this experience would have cured me, had it not been that at

the very instant when I had finally abandoned play-writing I was engaged by the

Gaiety Theatre management. It was the same old Hey, Bill! business, but varied

this time by the fact that one had to climb up to the roof to get one’s weekly

stipend. Here, in a little room, sat a genial gentleman with a tableful of gold

in front of him. The sight of this wealth, though I only diminished it by two o’goblins

per week, so excited me that by the time the management hurled me into the

street for dilatoriness and inefficiency I was once more in the full grip of

the old malady. A commission to write a scene into “The Dollar Princess” (price

fifteen pounds) reduced me to a condition when only an operation could possibly

cure me.

The delirium was at its height when I went to New York in the spring of 1909; and shortly afterwards I wrote a novel called A Gentleman of Leisure. When an ex-actor and stage-director, living in my hotel, said he saw a play in it, he only endorsed my own view. We dramatised it together. A year later, after being refused by seven managers, it was accepted, and tried out at Newhaven, Connecticut. The denizens of Newhaven stood it like men, and the management decided that it should be put on for a run in New York. I may mention that the New York production took place quite a year after the play’s acceptance. There was no room for it at first.

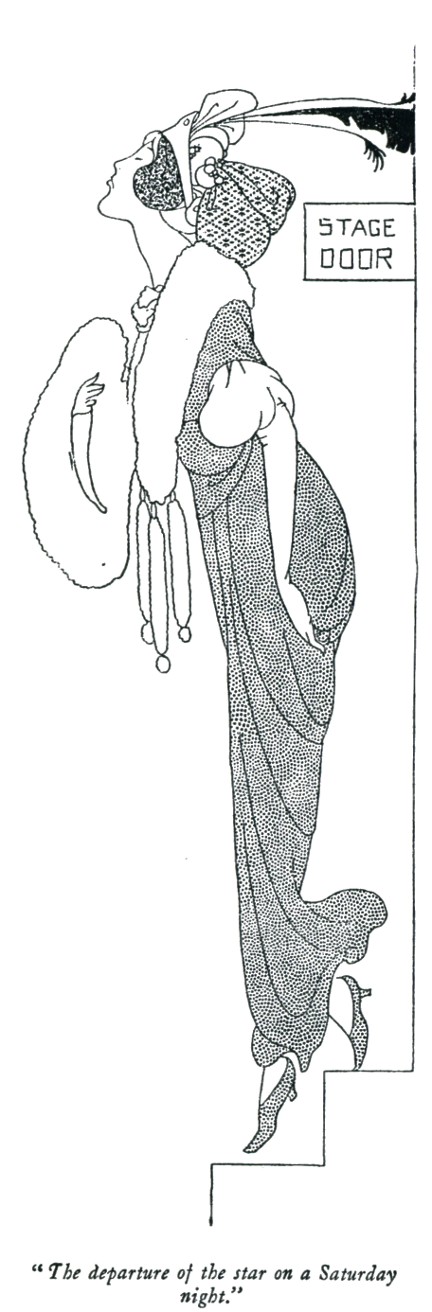

Between

Newhaven and New York all the men who had been Twenty Years In The Business

swooped down like eagles. The script was altered and re-altered; lines were

written in and taken out; everybody quarrelled with everybody else. Eventually

a sort of second edition of the piece was presented at the Playhouse. The

critics were on the whole favourable, and, the leading actor being popular with

the New York public, things looked prosperous until the management suddenly

transplanted the play to another theatre. It had just begun to take root again,

when off we had to go to a third theatre. Whether this would have killed us or

not of itself I do not know; but the coup de grâce was administered

by a quarrel between the star and the management, ending in the departure of

the star on the Saturday night. We struggled on for a week with a substitute,

and then died the death, after a hectic career on Broadway of about two

months. A very short tour followed and petered out; and since then the piece

has been playing intermittently in stock, an admirable institution leading to

unexpected cheques for £7 11s. 3d., £4 16s. 9d.,

and that kind of sum.

Between

Newhaven and New York all the men who had been Twenty Years In The Business

swooped down like eagles. The script was altered and re-altered; lines were

written in and taken out; everybody quarrelled with everybody else. Eventually

a sort of second edition of the piece was presented at the Playhouse. The

critics were on the whole favourable, and, the leading actor being popular with

the New York public, things looked prosperous until the management suddenly

transplanted the play to another theatre. It had just begun to take root again,

when off we had to go to a third theatre. Whether this would have killed us or

not of itself I do not know; but the coup de grâce was administered

by a quarrel between the star and the management, ending in the departure of

the star on the Saturday night. We struggled on for a week with a substitute,

and then died the death, after a hectic career on Broadway of about two

months. A very short tour followed and petered out; and since then the piece

has been playing intermittently in stock, an admirable institution leading to

unexpected cheques for £7 11s. 3d., £4 16s. 9d.,

and that kind of sum.

Everything seemed over, when the play was suddenly revived under another name in Chicago for five weeks, and played to fairly good business, thus improving matters rather after the fashion of a last-wicket stand.

My earnings from A Gentleman of Leisure came to about four hundred pounds; and unless the stock company at Indian’s Gulch, Arizona, or St. Petersburg, Massachusetts, decide to put it on for a week, I fancy that there is no more coming along.

My second operation took place quite recently in London, so recently that its humours have not yet become clear to me. Fifty pounds was my stipend.

Altogether, therefore, excluding the few pounds I managed to get away with before the Aldwych and Gaiety managements got on to the fact that they were paying me two pounds a week too much, my total earnings from the drama amount to—roughly—four hundred and sixty-five pounds.

Does that sum adequately recompense me for the time and labour expended? The answer, as Mr. Asquith would say, is in the negative.

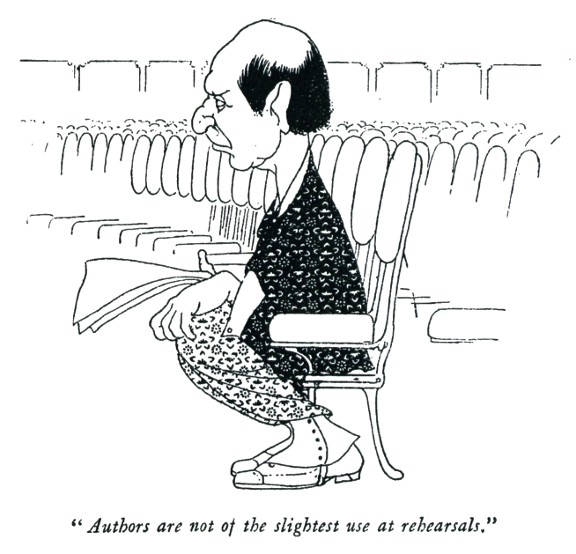

There

is only one way of approaching the stage from a writer’s point of view. That

is, to approach it from above. In other words, to stand no nonsense. And the

only way by which he may avoid the necessity of standing nonsense is to refuse

absolutely to mix himself up in the technical side of the business beyond

drawing his royalties. Let him, once his play has been accepted, resolutely

decline to alter a word of it. If necessary, let him sacrifice a portion of his

royalties to a horny-handed expert and permit him to do what is called the “fixing”

or—more humorously—the “getting the darned thing right, for Heaven’s

sake.” If the management object to this, to the point of returning the play,

let him pocket his hundred pounds forfeit-money and go on his way rejoicing as

one who has got himself out of a bad job. If the management still wish to

produce his piece, let him refuse to attend a single rehearsal.  Actors like to

have authors at rehearsals, but they are not of the slightest use. They look

grave and important, and nod sagely at intervals, but beyond that they are

ciphers. Staging a play is a purely professional undertaking, and the author,

in nine cases out of ten, is an amateur. He may understand enough about crosses

and positions to enable him to construct his play; but it is very rarely that

he has the ability to put it on the stage: and it will save him an infinity of

worry if he simply forgets about it till the first night, and leaves its

staging in the hands of Providence.

Actors like to

have authors at rehearsals, but they are not of the slightest use. They look

grave and important, and nod sagely at intervals, but beyond that they are

ciphers. Staging a play is a purely professional undertaking, and the author,

in nine cases out of ten, is an amateur. He may understand enough about crosses

and positions to enable him to construct his play; but it is very rarely that

he has the ability to put it on the stage: and it will save him an infinity of

worry if he simply forgets about it till the first night, and leaves its

staging in the hands of Providence.

The stage, from an author’s standpoint, is simply Monte Carlo with a few dozen extra zeros added. Look at his chances. The market is small: the stage is the only shop in which only one article can be exposed for sale at a time. This means that, even if his play is accepted, he will probably have to wait a long while for a production.

But suppose the play produced: this is really where the trouble begins. There are so few theatres that a management cannot pick and choose. It has to jump in wherever there is a vacancy; and the chances are greatly against the theatre thus acquired being the one most suitable for the piece which is to be produced. A farce needs a small house, a drama a large one. But if the Mammoth Theatre, usually reserved for musical comedy and melodrama, is the only available house, the promoters of The Joyous Eyebrow dare not let it slip, for there are only certain seasons when it is expedient to produce a play, and to refuse the Mammoth may mean postponing production for another six months. And to postpone for six months means that you lose the humorous Jones and the popular Miss Smith, neither of whom proposes to stroll about London till you are ready to employ them. So on goes The Eyebrow at the Mammoth, and starts accordingly with even more than the usual odds against it.

Then there is the chance that the humorous Jones may be funereally unfunny in this particular part, and that Miss Smith, so brisk and snappy in her last piece, may take her farce lines at comedy pace. The lighting may go wrong, or a hundred other things, causing a hitch in the first night’s performance. A week before the opening, a farce of much the same type may be produced at a rival theatre, taking the wind out of the sails of The Eyebrow. Producing a play is one long obstacle race.

Over none of these things has the author the slightest control. From a very early moment in the proceedings which eventually culminate in the first-night performance his fate is out of his hands. And it is this, more than anything else, which makes play-writing a poor business for a man who can do anything else.

Literature is said to be a good walking-stick, but a bad crutch. Play-writing is not even that. If other forms of literary work are to be described as a walking-stick, play-writing is a cracked cane. It is not safe to lean upon it.

No other public is so capricious as the theatrical. It is the custom with managers to rush with contracts to the author of a success. Why, it is difficult to say. It has been proved over and over again that an author very seldom produces two popular plays in succession. There is one American author whose first play was a big success on both sides of the Atlantic. His next four pieces ran one week each.

It is a truism to call theatrical work a gamble. In fact, the word gamble implies a certain sporting chance which the theatre does not really offer.

Why, then, is everybody writing plays? Partly, of course, because the prize of success is so enormous, if it ever comes; but principally because of the excitement of it. It is a business full of great moments. There is the moment when the play is accepted; the moment when you all travel down together to the country town in which the piece is to be tried out; the greatest moment of all, when the curtain rises on the first night. And there can be nothing like a first-night success for filling a man with a feeling of quiet benevolence towards all created things.

But it is a hobby, not a business. It is no more a business than yachting or racing or gambling at Monte Carlo. As soon as it is treated as a business, it becomes a disease, and the patient should be sent on a voyage round the world.

But even that would probably be of little use. He would see dramas in stones, farcical comedies in the running brooks. You would take him to the Taj Mahal, and he would step back, shade his eyes, and exclaim, “By Jove! What a setting for Act Two of a musical comedy!”

A moment later, you would miss him. Going in search, you would find him seated on a rock, writing feverishly. And, looking over his shoulder, you would see these words: “The Taj Mahal Girl. Act One, a Bond Street tea-shop. Opening chorus of flappers and nuts.”

P. G. Wodehouse.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums