The Pall Mall Magazine, May 1913

CLOUDLESS sky, a sea like satin. Air

that breathes the fragrance of eternal spring. White walls gleaming in the

sunshine; green hills towering to heaven. A Paradise, where falls not hail nor

any snow, nor ever wind blows loudly.

CLOUDLESS sky, a sea like satin. Air

that breathes the fragrance of eternal spring. White walls gleaming in the

sunshine; green hills towering to heaven. A Paradise, where falls not hail nor

any snow, nor ever wind blows loudly.

And, right in the middle of it all, a wretched little creature in a Homburg hat legging it back to his hotel for more money to spend at the Casino.

It is Nature’s comic relief, the Small Gambler.

If there is one spectacle more than another before which the gods, looking down on the follies of mankind, hesitate, uncertain whether to laugh or to weep, it is the spectacle of the Small Gambler at Monte Carlo trying to make his holiday expenses.

Gambling is so foreign to his nature. Home in England, he is so steady, so level-headed. He lives on a salary which he earns by honest work. Get-rich-quick schemes do not tempt him. He does not dabble in stocks. He does not even follow the races. But, once at Monte Carlo, he is another man.

Curiosity has brought him to Monte Carlo—that and the need for a change. He has not come to gamble. He knows better than that. All he means to do is to stroll into the Casino now and then after dinner, and see if he can’t make his expenses. But, if he loses, he will come straight out again. His attitude towards the Tables is going to be one of mild and detached amusement.

Bonehead!

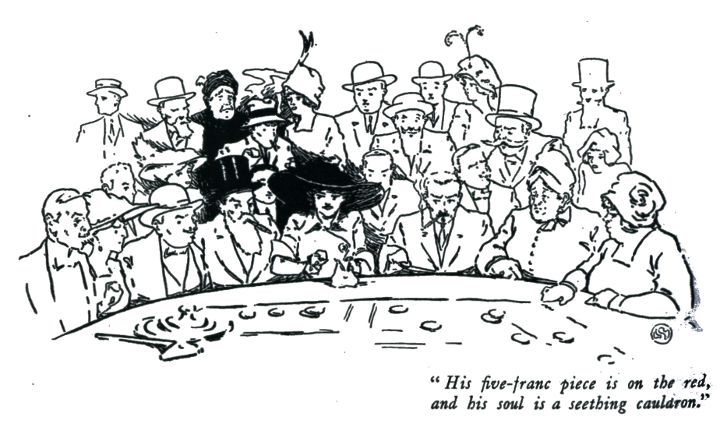

Observe him now. He has got that money, and is back again in the Casino. In company with some hundred other human sardines he is straining to keep a position near enough to a roulette-table to enable him to spend the twenty louis for which he went to his hotel just now. His face is flushed. His head is splitting. He has the ninepence-for-fourpence look. He has Shop-assistant’s Ankle through standing too long. He has Græco-Roman Wrestler’s Back-ache through wriggling about depositing his stake. He has Goal-keeper’s Squint through trying to watch his five-franc piece on red and the whirling ball simultaneously. He is a wreck.

The truth is that to preserve a detached attitude towards the gaming-table at Monte Carlo is impossible. Nobody has ever done it, and nobody ever will.

All that was settled years ago when M. Blanc selected Monte Carlo as the site for his Casino. If you put a Casino where that Casino is, then automatically the place, from the point of view of the ordinary man, becomes all Casino. Only by leaving the neighbourhood can he escape it. It is a case of Get In or Get Out.

Let me show the carefully-planned system by which the victim is shepherded to the tables.

Let me explain. At the back of Monte Carlo tower the eternal hills. Now, whatever else you may say about the eternal hills, however you may extol their grandeur and their impressiveness, the basic fact remains that they are hilly; and one of the most deeply-rooted instincts of man, if we except a handful of freaks who annually boost themselves over the Alps with sharpened hockey-sticks, is a dislike for walking uphill.

The visitor comes out of his hotel at Monte Carlo of a morning, merry and bright. He takes one look at the eternal hills, and his soul heaves. He turns quickly and goes the other way. This takes him direct to the Casino. That is why it is there.

He has now one last chance. By swerving to the right he can elude the Casino and reach the terrace. But the authorities have allowed for this. Just beyond the terrace they have placed the pigeon-traps, and the visitor, being a pretty decent fellow, is not entertained by the sight of people shooting legs and things off pigeons. He recoils. A minute later he is up the steps and in front of the Casino again. He hesitates. Then he takes a look over his shoulder at those eternal hills, shudders, and walks in.

Inside the building the authorities display a good deal of sardonic humour. A simulated coyness is their first joke. They know that they want the visitor’s money, and they know that they mean to get it, but they make as much fuss about starting in on him as a London, Chatham and Dover train does about entering a terminus. Their whole demeanour seems to indicate an agonised uncertainty. It is as if a brigand should pause and ask for guidance from above before going through his victims’ pockets.

The visitor goes to a counter on the left, answers questions, is scrutinised, signs his name: goes to a counter on the right, is scrutinised, signs his name again. Then, with the air of men embarking on a great adventure against their better judgment, the authorities give him a card of admission.

But, even now they have not entirely flung away caution. The same solemn farce has to be gone through next day, and the day after that. On the fourth day, wearying of the fun, they let him have an entrance ticket for a month. The wags! They know a week will be his limit.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the Tables! The Temple of Chance. The Plague Spot of Europe.

Here we are, all in amongst the Russian grand-dukes and gorgeously-dressed adventuresses, and—and well, anyhow, we ought to be. This is certainly the Casino. No doubt about that. But if there are grand-dukes about, they don’t look the part; and, if adventuresses are present, the gorgeous dresses must be at the cleaner’s today.

To be absolutely frank, this is about the seediest collection of dead-beats into which we have ever been introduced. For the last time, if there is a grand-duke here, let him stand forth.

No answer.

Adventuresses will oblige by identifying themselves in a clear voice.

Dead silence.

Then either we have been shamefully deceived by Monte Carlo novelists, or else these glittering personages must have gone on into the inner rooms. We cannot follow, to make certain, for the entrance-fee is two louis, and we are the Small Gambler, to whom two louis means eight stakes. Let us make the best of it, and take a look at the room in which we find ourselves.

There was a music-hall song a few years ago, the refrain of which began, “I’m leaving Monte Carlo. I can no longer stay.” (Today’s heart-cry!) The first line of the first verse was—

Outside the gay Casino . . .

The gay Casino! It is all the fault of those novelists. They misled the poor fellow, as they have misled thousands more. Their stories conjured up the Casino as a home of jovial revelry—tempered, true, by an occasional suicide, but on the whole distinctly jovial revelry. One pictured the merry cries, the babel of talk, the ringing laughs, and all that, a sort of blend of some gay French salon and the “Cottar’s Saturday Night.”

Well, it is not like that. Imagine the reading-room at the British Museum deadly quiet, heated up to about the temperature of the second room in a Turkish bath, and peopled with the inmates of the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud’s come to life. That’s the gaming-room at Monte Carlo.

It is a large room, with a parquet floor and some pretty pictures. Against the walls are the settees. In this room, you must understand, except for one or two brief intervals during the day, when the Small Gambler drops off like an exhausted limpet and goes and feeds himself, there are never fewer than a thousand people.

At each of the tables there is seating accommodation for about twenty. For the remainder, the wretched persons with Shop-assistant’s Ankle and Græco-Roman Wrestler’s Back-ache, there are these settees. On each settee two are comfortable, three a squash. For the tired multitude the management provides four settees.

It is all part of the system which started with those eternal hills. Outside the Casino everything forces you inside. Inside everything forces you to the tables. And, once you are at the tables, human nature does the rest.

This is the reason for the shortage of seats. The idea is to make the Small Gambler so uncomfortable that he loses all that calm detachment of his, and has to gamble in order to make himself to endure his surroundings—just as in a smoky railway-carriage he would light a cigar to keep himself from suffocating.

The sight of his companions does nothing to alleviate his discomfort. I do not wish to give offence or to seem even for a moment to appear to be in danger of saying anything remotely personal, but why is it that five out of ten of the denizens of the Monte Carlo Casino are so totally unlike anything on earth?

I know the authorities are capable of going to infinite trouble to harass the Small Gambler, but I cannot believe that they hire these extraordinary people to sit there, just to worry him. And yet it may be so.

The fact remains that the sight of them puts the last touch to the Small Gambler’s demoralisation. Two minutes later, with set teeth and a damp brow, he is watching the wheel rotate. He is no longer calm and detached. No more does he look on with mild amusement. His five-franc piece is on red, and his soul is a sort of seething cauldron in which dance the following thoughts:

(a) Shall I win?

(b) Black turned up last spin, so red ought to this. On the other hand, black may be in for a run.

(c) Suppose I win, and the croupier collars my doubloon!

(d) Suppose I win, and the croupier pays up like a man, and then that freak in front of me with a face like a walnut and a mouth like a scar pinches my winnings!

(e) How shall I prove they’re mine?

(f) He’s much nearer the table than I am. He could grab them in a second.

(g) I’ve heard of that sort of thing. It’s always being done.

(h) I wish I hadn’t come.

By this time he has worked himself up into such a state of mind with respect to the walnut-faced one that it is almost a relief when black turns up and he loses.

As a matter of fact, his suspicions were quite unjust—a face like a walnut may cover an honest heart. Stake-grabbing does happen occasionally at Monte Carlo, but it is so rare that the Small Gambler need not worry himself about it. He will find plenty else to worry about. The management will not stint him in this respect.

Another thing that is singularly rare at the Casino is Trouble. Frequently one sees men snarling and gabbling at each other for a few seconds, and then subsiding into grunt-punctuated silence, but a genuine fracas is almost unknown.

When it does happen, the authorities handle it in masterly fashion. Plain-clothes detectives spring up from nowhere, surround the offender, edge him away down the room, and bring him to anchor in a small apartment off the main entrance. Here everybody talks at once, and finally the trouble-merchant is persuaded to leave the Casino. He is never allowed in again. Lucky fellow! That sort of thing never happens to the Small Gambler.

It is a curious existence, the Small Gambler’s, unintelligible to the regular habitué of Monte Carlo. He who might be expected to haunt the tables incessantly seldom goes near them. At one time he too may have been a Small Gambler, but he has got over it now, and to him Monte Carlo is simply a place where there is always sunshine and always plenty to do. He is there for the winter, and he settles down to a regular life. He golfs, motors, yachts, and would be horrified at the idea of stifling himself in the Casino in the daytime.

But the Small Gambler is differently situated. He is not there for the winter. A fortnight is the limit he has fixed for his stay, and it is improbable that, once back in England, he will return for years, if at all.

It is now or never with him. Once he has taken the plunge, he eats, drinks and sleeps small gambling. He collects mascots. He talks Casino at meals to other Small Gamblers. He avoids the Café de Paris, the Carlton and the Austria, for these things would keep him up late, and militate against an early entrance next morning at the Casino.

A curious existence. One pictures him as a sort of fakir, one of those Indians who, doubtless from the best motives, spend their time hanging from a beam over a smouldering fire. While the fever lasts, he is just as effectually cut off from real life, and almost as uncomfortable.

My heart bleeds for the Small Gambler. We left him, if you recollect, wedged into the crowd, five francs to the bad, flushed and feverish. Nothing can save him now. He has lost money. He has a deficit to make up. From now on he will spend all day and every day at the tables, trailing that deficit like a blood-hound.

There will be moments when he will have it almost within his grasp. Then it will elude him again. And the longer it eludes him, the longer it will grow, until in the end he will have abandoned altogether his first happy dream of making his expenses, and will consider himself lucky if he can get all square again before the end of his visit.

But he will not. He cannot. That is the tragedy of the Small Gambler. To win at the tables needs dash, and the Small Gambler has no dash. He is trying to do the whole trip, fare included, on a fixed sum, and he becomes of necessity a piker, or, if you prefer it, a tinhorn sport, or one subject to cold feet. In other words, he is crippled by the necessity of having to economise. He cannot take risks. And, as the bookmaker said, “If you don’t speccylate, you can’t accumylate.”

He tries to gamble prudently.

He tries to treat a lunatic ball as a reasonable human-being.

His attitude towards it is that of one arguing with a friend. “You’ve turned up black six times running,” he seems to say. “You must be sick of it now, surely. The sheer monotony will make you want a change.” And the ball fetches up at black for the seventh time.

The Small Gambler cannot rid himself of this feeling that what is monotonous to him must be monotonous to the ball. In theory he knows all about runs, but he cannot adjust his mind to the possibility of them in practice. To leave his stake on red or black when he has won, on the chance of its doubling and redoubling, is physically beyond him. He has no dash. He does not speculate, so he does not accumulate.

The even chances are the Small Gambler’s hunting-ground. Red and black: odd and even: over eighteen and under: he keeps to these; and his ineradicable fear of having his winnings stolen makes him confine his operations to the side of the table nearest which he happens to be standing.

To stand in the second row of humanity on the rouge-impair-manqué side, and fling a coin across the table on to even or black is beyond him. It is too like casting his bread upon the waters. It may return to him, but he cannot help feeling that those appalling-looking cut-throats over the way will scoop it up before he can utter a cry of remonstrance.

And even if they refrain, he will have to stretch forward to get his money, which means knocking the hat of the woman in front of him—a feat which after her last snarl of disapproval he simply has not the nerve to attempt. And this is a man who, home in England, knew no fear: who conducted himself in business crises more like a level-headed lion of the jungle than anything else.

Sometimes he will play on the two-to-one chances, the three columns and the first, second and third dozens. But how shall the Ethiopian change his skin, the leopard his spots, or the Small Gambler his timidity? He does not intend to plunge wildly on a two-to-one chance. He hedges. He places a coin on the first dozen, and another on the third, thus giving himself two chances out of three. If the first dozen turns up, he loses one coin and wins two. If the third dozen turns up, he wins two and loses one. If the second dozen turns up, the world grows suddenly cold and black. And if the ball, which can do everything except laugh, pops into zero, he feels as if he had been kicked in the face. This last tragedy generally drives him back to the colours again, where zero can do him no more harm than to put his stakes temporarily in prison.

And so he goes on, losing, winning, losing again, drawing level again, then falling definitely behind once more and staying there. He has no chance. All the time he plays with one eye on failure, with searchings of the heart, knowing that it is idiotic of him to gamble at all, and knowing also that it is still more idiotic if he does gamble not to give himself a chance by doing the thing thoroughly.

There is no hope for him. The Goddess of Luck may treat Reckless Rupert shamefully, but she does occasionally smile on him. Cautious Cuthbert simply disgusts her, and she scratches him off her visiting-list from the start.

He is beaten before he begins. His friends ought never to have allowed him to go to Monte Carlo at all.

But then, Monte Carlo is a place to which everybody goes once in his life. It is the one spot in the world where a man may get something for nothing. You are bound to catch its fascination like measles, and, also like measles, you are not likely to catch it more than once.

The place is a sort of Purgatory, where the prudent man is purged of that minimum of foolishness of which he has not been able to rid himself in any other way. Until he has actually been to Monte Carlo, he retains, in spite of himself, a secret belief that, if some day he did happen to go, he would make money, that he would bring to the tables the same strong intelligence and self-restraint which have made him so universally respected in—well, wherever he happens to be universally respected. There is one born every minute.

And then comes the last phase.

The patient’s recovery is curiously sudden.

One moment he is losing his money as if it were his settled job in life, his brain whirling with the visions of wiring to his bank for vast overdrafts and winning huge sums at the eleventh hour; the next, the fever has left him, suddenly in a flash he realises that he has worked harder at this imbecile game than he ever worked in his London office—that he has been paying good money simply to stand at a crowded table and get a shocking headache.

A restful calm steals over him. He is cured. And the convalescent, paying his hotel bill with the broken remnants of his little capital, grasps his return ticket and climbs happily into the Calais express. The great company of Small Gamblers has lost a member.

P. G. Wodehouse.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums