Pearson’s Magazine [UK], December 1914

I.

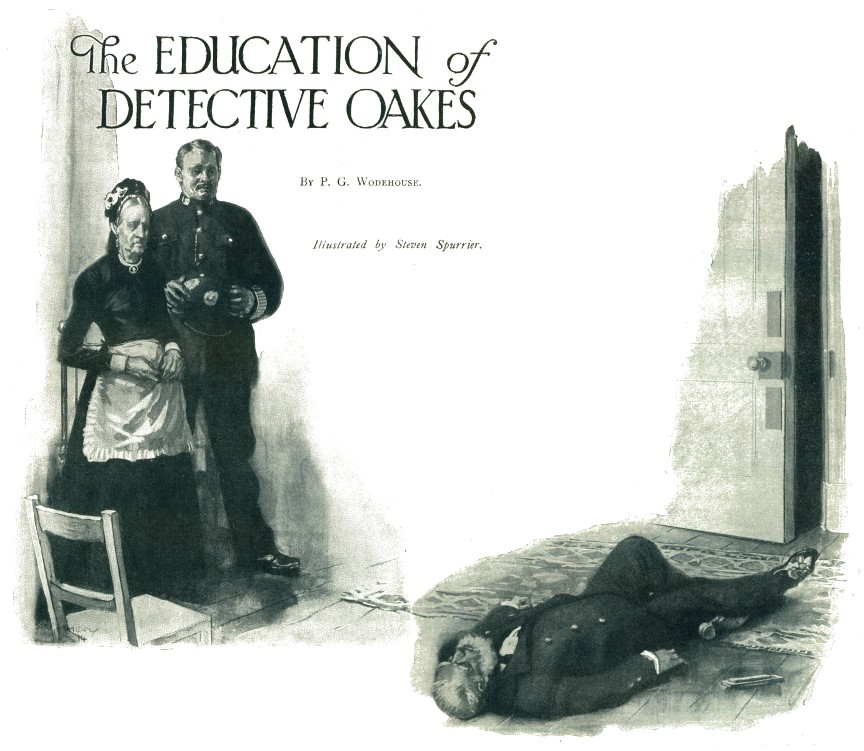

The room was the typical bedroom of the typical boarding-house, furnished, so far as it was furnished at all, with a severe simplicity. It contained two beds, a pine chest of drawers, a strip of faded carpet, and a wash-hand stand. All these things might have been guessed at from the other side of the closed door. But there was that on the floor which set this room apart from a thousand rooms of the same kind. Flat on his back, one leg twisted oddly under the other, his hands clenched and his teeth gleaming through his grey beard in a horrible grin, Captain John Gunner stared at the ceiling with eyes that saw nothing.

Until a moment before, he had had the little room to himself. But now two people were standing opposite the door, looking down at him. One was a large policeman, who twisted his helmet nervously in his hands. The other was a tall, gaunt old woman in a rusty black dress, who gazed with pale eyes at the dead man. Her face was quite expressionless.

The woman was Mrs. Pickett, owner of the Excelsior Boarding House. She had not spoken since she had brought the policeman into the room. He looked at her quickly. He was afraid of Mother Pickett, as was everybody else along the water-front. Her silence, her pale eyes, and the quiet formidableness of her personality cowed even the tough specimens of humanity who patronised the Excelsior. She was a queen in that little community of sailormen.

“That’s just how I found him,” said Mrs. Pickett. She did not speak loudly, but her voice made the policeman start.

He wiped his forehead. There was a sound of footsteps outside. A young man entered, carrying a black bag.

“Good morning, Mrs. Pickett. What’s the—good heavens!”

He dropped to his knees beside the body, and raised one of the arms. He lowered it gently to the floor, and shook his head.

“Been dead for hours. When did you find him?”

“Twenty minutes ago,” said the old woman. “I suppose he died last night. He never would be called in the morning. Said he liked to sleep on. Well, he’s got his wish.”

“What did he die of, sir?” asked the policeman.

The doctor eyed the body almost resentfully.

“I can’t understand it,” he said. “The man had no right to drop dead like this. He was a tough old sailor, who ought to have been good for another twenty years. If you ask me—though I can’t possibly be certain till after the inquest—I should say he had been poisoned.”

“How would he be poisoned?” said Mrs. Pickett.

“That’s more than I can tell you. There’s no glass about that he could have drunk it from. He might have got it in capsule form. But why should he have done it? He was always a pretty cheerful sort of old man, wasn’t he?”

“Yes, sir,” said the policeman. “He had the name of being a joker in these parts. Kind of sarcastic, they tell me, though he never tried it on me.”

“This man must have died quite early last night,” said the doctor. “What’s become of Captain Muller? If he shares this room he ought to be able to tell us something about it.”

“Captain Muller spent the night with some friends at Portsmouth,” said Mrs. Pickett. “He wasn’t here from after supper.”

The doctor looked round the room, frowning.

“I don’t like it. I can’t understand it. If this had happened in India, I should have said the man had died from some form of snake-bite. I was out there two years, and I’ve seen a hundred cases of it. They all looked just like this. The thing’s ridiculous. How could a man be bitten by a cobra or any other snake in a Southampton water-front boarding-house! The whole thing’s mad. Was the door locked when you found him, Mrs. Pickett?”

Mrs. Pickett nodded.

“I opened it with my own key. I had been calling to him and he didn’t answer, so I guessed something was wrong.”

The policeman spoke.

“You ain’t touched anything, ma’am? They’re always very particular about that. If this gentleman’s right, and there’s been anything up, that’s the first thing they’ll ask.”

“Everything’s just as I found it.”

“What’s that on the floor beside him?”

“That’s his harmonica. He liked to play it of an evening in his room. I’ve had complaints about it from some of the gentlemen, but I never saw any harm, so as he didn’t play too late.”

Another aspect of the matter seemed to strike the policeman.

“This ain’t going to do the Excelsior any good, ma’am,” he said sympathetically.

Mrs. Pickett shrugged her shoulders. Silence fell upon the room.

“I suppose I had better go and notify to the coroner,” said the doctor.

He went out, and, after a momentary pause, the policeman followed him. He was not greatly troubled with nerves, but he felt a decided desire to be somewhere where he could not see those staring eyes.

Mrs. Pickett remained where she was, looking down at the dead man. Her face was still expressionless, but inwardly she was in a ferment. This was the first time such a thing as this had happened at the Excelsior, and, as Constable Grogan had hinted, it was not likely to increase the attractiveness of the house in the eyes of possible boarders.

It was not the probable pecuniary loss which was troubling Mrs. Pickett. As far as money was concerned, she could have retired from business years before and lived comfortably on her savings. She was richer than those who knew her supposed. It was the blot on the escutcheon of the Excelsior, the stain on the Excelsior’s reputation, which was tormenting her. The Excelsior was her life. Starting many years before, beyond the memory of the oldest boarder, she had built up this model establishment, the fame of which had been carried to every corner of the world.

Such was the chorus of praise that it is not likely that much harm could come to Pickett’s from a single mysterious death, but Mother Pickett was not consoling herself with such reflections. She was wounded sore. Pickett’s had had a clean slate; now it had not. That was the sum of her thoughts. She looked at the dead man with pale, grim eyes.

II.

The offices of Mr. Paul Snyder’s Detective Agency in New Oxford Street had grown in the course of half-a-dozen years from a single room to a palatial suite, full of polished wood, clicking typewriters, and other evidences of success.

Mr. Snyder had just accepted a case. It seemed to him a case that might be nothing at all or something exceedingly big, and on the latter possibility he had gambled. The fee offered was, judged by his present standards of prosperity, small, but the bizarre facts, coupled with something in the personality of the client, had won him over; and he touched the bell and desired that Mr. Oakes should be sent in to him.

Elliot Oakes was a young man who amused and interested Mr. Snyder. He was so intensely confident. He was an American, and had only recently joined the staff, after a probationary period with the Pinkertons, and he made very little secret of his intention of electrifying and revolutionising the methods of the London Agency, which he considered typically slow and English. Mr. Snyder himself, in common with most of his assistants, relied for results on hard work and plenty of common-sense. He had never been a detective of the showy type. Results had justified his methods, but he was perfectly aware that young Mr. Oakes looked on him as a dull old man who had been miraculously favoured by luck.

Mr. Snyder had selected Oakes for the case in hand principally because it was one where inexperience could do no harm, and where the brilliant guess-work, which the New Yorker called his inductive reasoning, might achieve an unexpected success.

Another motive actuated Mr. Snyder in his choice. He had a strong suspicion that the conduct of this case was going to have the beneficial result of lowering Oakes’ self-esteem. If failure achieved this end Mr. Snyder felt that failure, though it would not help the Agency, would not be an unmixed ill.

The door opened and Oakes entered tensely. He did everything tensely, partly from a natural nervous energy and partly as a pose.

“Sit down, Oakes,” said Mr. Snyder, “I’ve a job for you.”

Oakes sank into a chair like a crouching leopard, and placed the tips of his fingers together. He nodded curtly. It was part of his pose to be keen and silent.

“I want you to go to this address”—he handed him an envelope—“and look round. The address on that envelope is of a sailors’ boarding-house down in Southampton. You know the sort of place. Retired sea-captains, and so on. All most respectable. In all its history nothing more sensational has ever happened than a case of suspected cheating at halfpenny nap. Well, a man has died there.”

“Murdered?”

“I don’t know. That’s for you to find out. The coroner left it open. ‘Death by Misadventure’ was the verdict, and I don’t blame him.”

“What was the cause of death?”

Mr. Snyder coughed.

“Snake-bite,” he said.

Oakes’ careful calm deserted him. He uttered a cry of astonishment.

“What!”

“It’s the literal truth. The medical examination proved that the fellow had been killed by snake-poison. To be exact, cobra-poison.”

“Cobra!”

“Just so. In a Southampton boarding-house, in a room with a locked door, this man was stung by a cobra. To add a little mystification to the limpid simplicity of the affair, when the door was opened there was no sign of any cobra. It couldn’t have got out through the door, because the door was locked. It couldn’t have got up the chimney, because there was no chimney. And it couldn’t have got out of the window, because the window was too high up, and snakes can’t jump. So there you have it.”

“I should like further details,” said Oakes a little breathlessly.

“You had better apply to Mrs. Pickett, who owns the boarding-house. It was she who put the case in my hands. She is convinced that it is murder. It’s not for me to turn business away. So, as I said, I want you to go and put up at Mrs. Pickett’s Excelsior Boarding House and do your best to put things straight. I would suggest that you pose as a ship’s chandler or something of that sort. You will have to be something maritime or they’ll be suspicious of you. And if your visit produces no other results, it will, at least, enable you to make the acquaintance of a very remarkable woman. I commend Mrs. Pickett to your notice. By the way, she says she will help you in your investigations.”

Oakes laughed shortly. The idea amused him.

“It is very kind of Mrs. Pickett, but I think I prefer to trust to my own powers of induction.”

Oakes rose. His face was keen and purposeful.

“I had better be starting at once,” he said, “I will mail you reports from time to time.”

“I shall be interested to read them,” said Mr. Snyder genially. “I hope your visit to the Excelsior will be pleasant. If you run across a man with a broken nose, who used to rejoice in the name of Horse-Face Simmons, give him my regards. I had the pleasure of sending him to prison some years ago for robbery with violence, and I understand that he has settled in those parts. And cultivate Mrs. Pickett. She’s worth while.”

The door closed, and Mr. Snyder lighted a fresh cigar.

“Dashed young fool,” he murmured, and turned his mind to other matters.

III.

A day later Mr. Snyder sat in his office reading a typewritten manuscript. It appeared to be of a humorous nature, for, as he read, chuckles escaped him. Finishing the last sheet he threw his head back and laughed heartily.

The manuscript had not been intended by its author for a humorous effort. What Mr. Snyder had been reading was the first of Elliott Oakes’ reports from the Excelsior:

“I am sorry,” wrote Oakes, “to be unable to report any real progress. I have formed several theories which I will put forward later, but up to the present I cannot say that I am hopeful.

“Directly I arrived here I sought out Mrs. Pickett, explained who I was, and requested her to furnish me with any further information which might be of service to me. She is a strange, silent woman, who impressed me as having very little intelligence. Your suggestion that I should avail myself of her assistance in unravelling this mystery seems more curious than ever, now that I have seen her.

“The whole affair seems to me at the moment of writing quite inexplicable. Assuming that this Captain Gunner was murdered, there appears to have been no motive for the crime whatsoever. I have made careful inquiries about him, and find that he was a man of fifty-five; had spent nearly forty years of his life at sea, the last dozen in command of his own ship; was of a somewhat overbearing and tyrannous disposition, though with a fund of rough humour; had travelled all over the world, and had been an inmate of the Excelsior for about ten months. He had a small annuity, and no other money at all, which disposes of money as the motive for the crime.

“In my character of James Burton, a retired ship’s chandler, I have mixed with the other boarders, and have heard all they have to say about the affair. I gather that the deceased was by no means popular. He appears to have had a bitter tongue, and I have not met one man who seems to regret his death. On the other hand, I have heard nothing which would suggest that he had any active and violent enemy. He was simply the unpopular boarder—there is always one in every boarding-house—but nothing more.

“I have seen a good deal of the man who shared his room. He, too, is a sea captain, by name Muller. He is a big, silent German, and it is not easy to get him to talk on any subject. As regards the death of Captain Gunner he can tell me nothing. It seems that on the night of the tragedy he was away at Portsmouth with some friends. All I have got from him is some information as to Captain Gunner’s habits, which leads nowhere. The dead man seldom drank, except at night when he would take some whisky. His head was not strong, and a little of the spirit was enough to make him semi-intoxicated, when he would be hilarious and often insulting. I gather that Muller found him a difficult room-mate, but he is one of those placid Germans who can put up with anything. He and Gunner were in the habit of playing draughts together every night in their room, and Gunner had a harmonica which he played frequently. Apparently, he was playing it very soon before he died, which is significant, as seeming to dispose of the idea of suicide.

“But, if Captain Gunner did not kill himself, I cannot, at present, imagine who did kill him, or why they killed him, or how. As I say, I have one or two theories, but they are in a very nebulous state. The most plausible is that on one of his visits to India—I have ascertained that he made several voyages there—Captain Gunner may in some way have fallen foul of the natives. Kipling’s story, ‘The Mark of the Beast,’ is suggestive. Is it not possible that Captain Gunner, a rough, overbearing man, easily intoxicated, may in a drunken frolic have offered some insult to an Indian god? The fact that he certainly died of the poison of an Indian snake supports this theory. I am making inquiries as to the movements of several Indian sailors who were here in their ships at the time of the tragedy.

“I have another theory. Does Mrs. Pickett know more about this affair than she appears to? I may be wrong in my estimate of her mental qualities. Her apparent stupidity may be cunning. But here, again, the absence of motive brings me up against a dead wall. I must confess that at present I do not see my way clearly. However, I will write again shortly.”

Mr. Snyder derived the utmost enjoyment from the report. He liked the matter of it, and he liked Oakes’ literary style. Above all, he was tickled by the obvious querulousness of it. Oakes was baffled, and his knowledge of Oakes told him that the sensation of being baffled was gall and wormwood to that high-spirited young gentleman.

He wrote his assistant a short note:

Dear Oakes,—

Your report received. You certainly seem to have got the hard case which, I hear, you were pining for. Don’t build too much on plausible motives in a case of this sort. Fauntleroy, the London murderer, killed a woman for no other reason than that she had thick ankles. Many years ago I, myself, was on a case where a man murdered an intimate friend because of a dispute about a bet. My experience is that five murderers out of ten act on the whim of the moment, without anything which, properly speaking, you could call a motive at all.

Yours, Paul Snyder.

P.S.—I don’t think much of your Pickett theory. However, you’re in charge. I wish you luck.

IV.

Young Mr. Oakes was not enjoying himself. For the first time in his life he was beginning to be conscious of the possession of nerves. He had gone into this investigation with the self-confident alertness which characterised all his actions. He believed in himself thoroughly.

This mood had lasted for some hours. Then doubts had begun to creep in.

He was baffled. And every moment which he spent in the Excelsior Boarding House made it clearer to him that that infernal old woman with the pale eyes thought him an incompetent fool. It was this more than anything which had brought to Elliott Oakes’ notice the fact that he had nerves. Those nerves were being sorely troubled by the quiet scorn of Mrs. Pickett’s gaze.

Elliott Oakes’ first act after his brief interview with the proprietress had been to examine the room where the tragedy had taken place. The body had gone, but, with that exception, nothing had been moved.

Oakes belonged to the magnifying-glass school of detection. The first thing he did on entering the room was to make a careful examination of the floor, the walls, the furniture, and the window-sill. He would have hotly denied the assertion that he did this because it looked well, but he would have been hard put to it to advance any other reason.

If he discovered anything, his discoveries were entirely negative, and served only to deepen the mystery of the case. As Mr. Snyder had said, there was no chimney, and nobody could have entered through the locked door.

There remained the window. It was small, and apprehensiveness, possibly on the score of burglars, had caused the proprietress to make it doubly secure with an iron bar. No human being could have squeezed his way through it.

It was late that night that he wrote and dispatched to headquarters the report which had amused Mr. Snyder.

V.

Two days later Mr. Snyder sat in his office. There was a telegram before him. It ran as follows:

“Have solved Gunner mystery. Returning.—Oakes.”

Mr. Snyder rang the bell.

“Send Mr. Oakes to me directly he arrives,” he said.

He put his feet up on the desk, tilted his chair back, and frowned at the ceiling. He was pained to find that the chief emotion with which the telegram from Oakes had affected him was annoyance. The swift solution of such an apparently insoluble problem would reflect the highest credit on the Agency, and there were picturesque circumstances connected with the case which would make it popular with the newspapers and lead to its being accorded a great deal of publicity.

On the whole, no case of recent years promised to give the Agency a bigger advertisement than this one. Yet, in spite of all this, Mr. Snyder was annoyed.

He realised now how large a part the desire to reduce Oakes’ self-esteem had played with him. Looking at the thing honestly, he owned to himself that he had had no expectation that the young man would come within a mile of a reasonable solution of the mystery, and he had calculated that his failure would prove a valuable piece of education for him. Mr. Snyder looked forward with apprehension to the young man’s probable demeanour under the intoxicating influence of victory.

His apprehensions were well grounded. He had barely finished the second of the series of cigars which, like milestones, marked the progress of his afternoon, when the door opened and Oakes entered, rampant. Mr. Snyder could not repress a faint moan at the sight of him. One glance was enough to tell him that his worst fears were realised.

“I got your telegram,” said Mr. Snyder.

Oakes nodded.

“It surprised you, eh?”

Mr. Snyder resented the patronising tone of the question, but he had resigned himself to being patronized, and gave no sign of his resentment.

“Yes,” he replied. “I must say it did surprise me. I didn’t gather from your report that you had even found a clue. Was it the Indian theory that turned up trumps, or have you snared Mrs. Pickett?”

Oakes laughed tolerantly.

“Oh, that was all moonshine! I never really believed that truck. I put it in to fill up. I hadn’t begun to think about the case then—not really think.”

Mr. Snyder extended his cigar-case.

“Light up, and tell me all about it.”

“Well, I won’t say I haven’t earned this,” said Oakes, puffing smoke. “Shall I begin at the beginning?”

“Do. But just tell me first, who was it did it? Was it one of the boarders?”

“No.”

“Somebody from outside, then?”

Oakes smiled quietly.

“Yes, you might call it somebody from outside. But I had better trace my reasoning from the start.”

“That’s right. It spoils a story, knowing the finish. Go ahead.”

Oakes let the ash of his cigar fall delicately to the floor—another action which seemed significant to his employer. As a rule, his assistants, unless particularly pleased with themselves, used the ash-tray.

“My first act on arriving,” he said, “was to have a talk with Mrs. Pickett. A very dull old woman.”

“Curious. She struck me as rather intelligent.”

“Not on your life. She doesn’t know beans from buttermilk. She gave me no assistance whatever. I then examined the room where the death had taken place. It was much as you had described it. Locked door. Window high up. No chimney. I’m bound to say, at first sight, it looked fairly unpromising. Then I had a chat with some of the other boarders. They had nothing to tell me that was of the least use. Most of them simply gibbered. I then gave up trying to get help from outside, and resolved to rely on my own intelligence.”

He smiled complacently.

“It is a theory of mine, Mr. Snyder, which I have found valuable, that, in nine cases out of ten, remarkable things don’t happen.”

“I don’t quite follow you there.”

“I mean exactly what I say. I will put it another way, if you like. What I mean is that the simplest explanation is nearly always the right one.”

“Well, I don’t——”

“I have tested and proved it. Consider this case. Was there ever a case which was more entitled by rights to a bizarre solution? One was almost inclined to believe in the supernatural. It seemed impossible that there should have been any reasonable explanation of the man’s death. Most men would have worn themselves out guessing at wild theories. If I had started to do that, I should have been guessing now. As it is—here I am. I trusted to my belief that nothing remarkable ever happens, and I won out.”

Mr. Snyder sighed softly. Oakes was entitled to a certain amount of gloating, but there was no doubt that his way of telling a story was a little trying.

“I believe in the logical sequence of events. I refuse to accept effects unless they are preceded by causes. In other words, with all due deference to you, Mr. Snyder, I simply decline to believe in a murder unless there is a motive for it. The first thing I set myself to ascertain was, what was the motive for this murder of Captain Gunner? And, after thinking it over and making every possible inquiry, I decided that there was no motive. Therefore, there was no murder. It was like an elementary sum.”

Mr. Snyder’s mouth opened, and he apparently intended to speak, but he changed his mind, and Oakes proceeded.

“I then tested the suicide theory. What motive was there for suicide? There was no motive. Therefore, there was no suicide.”

This time Mr. Snyder spoke.

“My boy, you haven’t been spending the last few days at the wrong house by any chance, have you? You will be telling me next that there wasn’t any dead man.”

Oakes smiled.

“Not at all. Captain John Gunner was as dead as mutton, and, as the medical evidence proved, he died of the bite of a cobra.”

Mr. Snyder shrugged his shoulders.

“Go on,” he said. “It’s your story. I’m listening.”

“Well, I won’t keep you long. Captain Gunner died from snake-bite for the very excellent reason that he was bitten by a snake.”

“Bitten by a snake?”

“By a cobra. If you want further details, by a small cobra which came from Java.”

Mr. Snyder stared at him.

“How do you know?”

“I do know.”

“Did you see the snake?”

“No.”

“Then how——?”

“I have enough evidence to make a jury convict Mr. Snake without leaving the box.”

“How did the cobra get out of the room?”

“By the window.”

“How do you make that out? You say yourself that the window was high up.”

“Nevertheless, it got out by the window. It’s the logical sequence of events again. There’s proof enough that it was in the room. It killed Captain Gunner there. And there’s proof enough that it got out of the room, because it left traces of its presence outside. Therefore, as the window was the only exit, it must have got out that way. It may have climbed or it may have jumped, but it got out of the window.”

“What do you mean—proofs of its presence outside?”

“It killed a cat and a dog.”

“Hullo! This is new. You didn’t mention them before.”

“No.”

“How do you know it killed the cat and the dog?”

“Because analysis proved that both had died from snake-bite.”

“Where were they?”

“There is a sort of back-yard behind the house. The window of Captain Gunner’s room looks out on to it. It is full of boxes and litter of all sorts, and there are a few stunted shrubs scattered about. In fact, there is enough cover to hide any small object like the body of a cat or a dog, and that’s why they were not discovered at first. Jane, the help at the Excelsior, came on them the morning after I had sent you my report, while she was emptying a box of ashes in the yard. The cat was identified as belonging to Captain Muller, the German I mentioned in my report, who shared Captain Gunner’s room. It had been missing for several days. Nobody claimed the dog. It was just an ordinary dog. I don’t suppose it belonged to anybody. It had no collar.”

“It was fortunate you happened to think of having the analysis made.”

“No, sir. It was the obvious thing to do. If there had been only a dead cat or only a dead dog I don’t say that I might not have overlooked it. One dead animal is natural. Two constitute a coincidence, and I was on the look-out for that sort of coincidence. It supported my theory. Well, as I say, the analyst examined both bodies and found that the cat and dog had both died of the bite of a cobra.”

“But you didn’t find the snake?”

“No. We cleaned out that yard till you could have eaten your breakfast there, but the snake had gone.”

“Good heavens! Is it wandering at large along the water-front?”

“We’ll hope it has been killed. It’s not a pleasant thing to have about the streets. It must have got out through the door of the yard, which was open. But it is a couple of days now since it escaped, and there has been no further tragedy, so I guess it’s dead. The nights are pretty cold now, and it would probably have died of exposure. Anyway, let’s hope so.”

“But, for goodness’ sake, how did a cobra get to Southampton?”

“There is a very simple explanation of that. Can’t you guess it? I told you it came from Java.”

“How do you know that?”

“Captain Muller told me. Not directly, I don’t mean. I gathered it from what he said. It seems that Captain Muller has a friend, an old shipmate, living in Java. They correspond, and occasionally this man sends the captain a present as a mark of his esteem. The last present he sent him was our friend the snake.”

“What!”

“He didn’t know he was sending it. He imagined he was sending a crate of bananas, without any extras. Unfortunately the snake must have got in unnoticed. That’s why I told you the cobra was a small cobra. These unsuspected additions to crates of bananas are quite common. You must have read about them in the papers. It was only the other day that a man found a tarantula inside one. Well, that’s my case against Mr. Snake, and, short of catching him with the goods, I don’t see how I could have made out a stronger one. Don’t you agree with me?”

It went against the grain for Mr. Snyder to play the rôle of admiring friend to his assistant’s triumphant detective, but he was a fair-minded man, and he was forced to admit that Oakes did certainly seem to have solved the insoluble.

“I congratulate you, my boy,” he said, as heartily as he could. “I’m bound to say, when you started, I didn’t think you could do it. How did you leave the old lady? I suppose she was pleased?”

“She didn’t show it. She’s only half alive, that woman. She hasn’t sense enough to be pleased at anything. However, she has invited me to dine to-night in her own private room, which, I suppose, is an honour. It will certainly be a bore. Still, I accepted. She made such a point of it.”

VI.

For some time after Oakes had gone Mr. Snyder sat smoking and thinking. His meditations were not altogether pleasant. Oakes, he felt, after this would be unbearable as a man, and, what was worse from a professional view-point, of greatly diminished value as a servant of the Agency. What Oakes most needed at this point in his education was a failure which should keep his self-confidence in check.

To Mr. Snyder, meditating thus, there was brought the card of a caller. Mrs. Pickett would be glad if he could spare her a few moments.

She came in. Her eyes had the penetrating stare which in the early periods of the investigation had disconcerted Elliott Oakes. She gave Mr. Snyder, an expert in the difficult art of weighing people up, an extraordinary impression of reserved force.

“Sit down, Mrs. Pickett,” said Mr. Snyder genially. “Very glad you looked in. Well, so it wasn’t murder at all.”

“Sir?”

“I’ve just been seeing Mr. Oakes,” explained the detective. “He has told me all about it.”

“He told me all about it,” said Mrs. Pickett drily.

Mr. Snyder looked at her inquiringly. Her manner seemed more suggestive than her words.

“A conceited, headstrong young fool,” said Mrs. Pickett.

It was no new picture of his assistant that she had drawn. Mr. Snyder had often drawn it himself, but at the present juncture it surprised him. Oakes, in his hour of triumph, surely did not deserve this sweeping condemnation.

“Did not Mr. Oakes’ solution of the mystery satisfy you, Mrs. Pickett?”

“No.”

“It struck me as logical and convincing.”

“You may call it all the fancy names you please, Mr. Snyder, but it was not the right one.”

“Have you an alternative to offer?”

“Yes.”

“I should like to hear it.”

“At the proper time you shall.”

“What makes you so certain that Mr. Oakes is wrong?”

“He takes for granted what isn’t possible, and makes his whole case stand on it. There couldn’t have been a snake in that room, because it couldn’t have got out. The window was too high.”

“But surely the evidence of the dead cat and dog?”

Mrs. Pickett looked at him as if he had disappointed her. “I had always heard you spoken of as a man with common-sense, Mr. Snyder.”

“I have always tried to use common-sense.”

“Then why are you trying now to make yourself believe that something happened which could not possibly have happened, just because it fits in with something which isn’t easy to explain?”

“You mean that there is another explanation of the dead cat and dog?”

“Not another. Mr. Oakes’ is not an explanation. But there is an explanation, and if he had not been so headstrong and conceited he might have found it.”

“You speak as if you had found it.”

“I have.”

Mr. Snyder started. “You have!”

“Yes.”

“What is it?”

“You shall hear when I am ready to tell you. In the meantime, try and think it out for yourself. A great detective agency like yours, Mr. Snyder, ought to do something in return for a fee.”

There was something so reminiscent of the school-teacher reprimanding a recalcitrant urchin that Mr. Snyder’s sense of humour came to his rescue.

“Well, we do our best, Mrs. Pickett. We are only human. And, remember, we guarantee nothing. The public employs us at its own risk.”

Mrs. Pickett did not pursue the subject. She waited grimly till he had finished speaking and then proceeded to astonish Mr. Snyder still further.

“What I came for,” she said, “was to ask you to swear out a warrant for arrest. You know how these things are done, I don’t.”

“A warrant for arrest!”

“For murder.”

“But—but—my dear Mrs. Pickett, whom on earth do you want to have arrested for murder?”

“One of my boarders—Captain Muller.”

Mr. Snyder’s breath was not often taken away in his own office; as a rule, he received his clients’ communications, strange as they often were, calmly, but at these words he gasped. The thought crossed his mind that Mrs. Pickett was not quite sane. The details of the case were fresh in his memory, and he distinctly recollected that this Captain Muller had been away from the boarding-house on the night of Captain Gunner’s death, and, he imagined, could bring witnesses to prove as much, if necessary.

“Captain Muller!” he echoed.

Mrs. Pickett was regarding him with an unfaltering stare. To all outward appearance, she was sane.

“But you can’t swear out warrants without evidence.”

“I have evidence.”

“What is it?”

“If I told you now you would think that I was out of my mind. Captain Muller will not.”

“But, my dear madam, do you realise what you are asking me to do? I cannot make this Agency responsible for the casual arrest of people in this way. It might ruin me. At the least, it would make me a laughing-stock.”

“Mr. Snyder, listen to me. You shall use your own judgment whether or not you arrest Captain Muller on that warrant. You shall hear what I have to say to Captain Muller, and you shall see for yourself how he takes it. If, after that, you feel that you cannot arrest him, you need do nothing.”

Her voice rose. For the first time since they had met, she began to throw off the stony calm which served to mask all her thoughts and emotions.

“I know Captain Muller killed Captain Gunner; I can prove it. I knew it from the beginning. It was like a vision. Something told me. But I had no proof. Now things have come to light and everything is clear.”

Against his judgment, Mr. Snyder was impressed. This woman had the magnetism which makes for persuasiveness. He wavered.

“It—it sounds incredible.”

Even as he spoke, he remembered that it had long been a professional maxim of his that nothing was incredible, and he weakened still further.

“Mr. Snyder, I ask you to swear out that warrant.”

The detective gave in. “Very well.”

Mrs. Pickett rose. “If you will come down to Southampton and dine at my house to-night, I think I can prove to you that it will be needed. Will you come?”

“I’ll come,” said Mr. Snyder.

VII.

When Mr. Snyder arrived at the Excelsior and was shown into the little private sitting-room where the proprietress held her court on the rare occasions when she entertained, he found Oakes already there. Oakes was surprised.

“What! Are you invited, too?” he said. “Say, I guess that this is her idea of winding up the case formally. A sort of Old Home Week celebration for all concerned.” He laughed.

Mr. Snyder did not reply. It struck Oakes that his employer was preoccupied and nervous. He would have inquired into this unusual frame of mind, but at that moment Captain Muller, the third guest of the evening, entered.

Mr. Snyder looked curiously at the newcomer. The big German, for whose arrest on a capital charge he had the warrant in his pocket, had a morbid interest for him.

Oakes did the honours.

“Captain Muller, I want you to know my friend, Mr. Snyder, if he will allow me to call him that. Perhaps I had better say my boss—Mr. Snyder employs me. You’ve heard of Snyder’s Detective Agency, captain? Oh, yes, I guess I may as well come out into the open now. My name isn’t Burton, and I’m not a ship’s chandler. In fact, I’m not sure that I know what a ship’s chandler is. You’re a maritime person, captain; perhaps you can tell me how you chandle ships? My name’s Oakes, and I’m one of Mr. Snyder’s staff. I was sent here to look into the death of your friend, Captain Gunner.”

Mr. Snyder wished profoundly that Oakes would not babble. The only consolation he had was that Oakes’ monologue had enabled him to take stock of this suspect. All the time that his assistant had been speaking, Mr. Snyder had been scrutinising Muller keenly.

The German was an interesting study to one in the detective’s peculiar position. It was not Mr. Snyder’s habit to trust overmuch to appearances, but he could not help admitting that there was something about this man’s aspect which brought Mrs. Pickett’s charges out of the realm of the fantastic into that of the possible. Here, to a student of men like Mr. Snyder, was obviously a man with something on his mind. His eyes were dull, his face haggard.

The door opened, and Mrs. Pickett came in. She made no apology for her lateness.

They took their seats at the table. Beside each of the guests’ plates was a neat parcel. The attitude of the three men towards these formed a curious index to the state of their feelings. Oakes picked his up, shook it, and smiled. Mr. Snyder touched his suspiciously, and frowned. The German ignored his altogether.

“What’s this, ma’am?” said Oakes, buoyantly. “Presents? Souvenirs? I call this very handsome of you, Mrs. Pickett. Do we open them?”

“Wait,” said Mrs. Pickett, and Oakes waited. He felt damped. He was in high spirits, and nobody seemed to respond.

They made a curious quartette. Oakes, struggling bravely to overcome his boredom, waxed loquacious. The old woman sat at the head of the table, grimly silent, a brooding, inscrutable figure. On her right, Mr. Snyder, mysteriously deprived of his usual easy geniality, crumbled bread. The German was drinking heavily.

Oakes sympathised with Captain Muller, and made a mental note to follow his example, unless things brightened up very shortly. He made one last effort to galvanise the party into life. He picked up his souvenir.

“I can’t wait any longer, Mrs. Pickett,” he said. “I have got to see what’s in it.”

“Very well,” said the old woman.

Oakes tore the wrappings, and produced a silver match-box.

“Thank you, ma’am, kindly,” he said. “Just what I’ve always wanted. What’s yours, Mr. Snyder? The same? Come along, captain. Open yours. I guess it’s something special. It’s four times the size of ours, anyway.”

It may have been something in the old woman’s expression as she watched the German slowly tearing the paper that sent a sudden thrill of excitement through Mr. Snyder. Something seemed to warn him of the approach of a psychological moment. He bent forward eagerly. Under the table his hands were clutching his knees in a bruising grip.

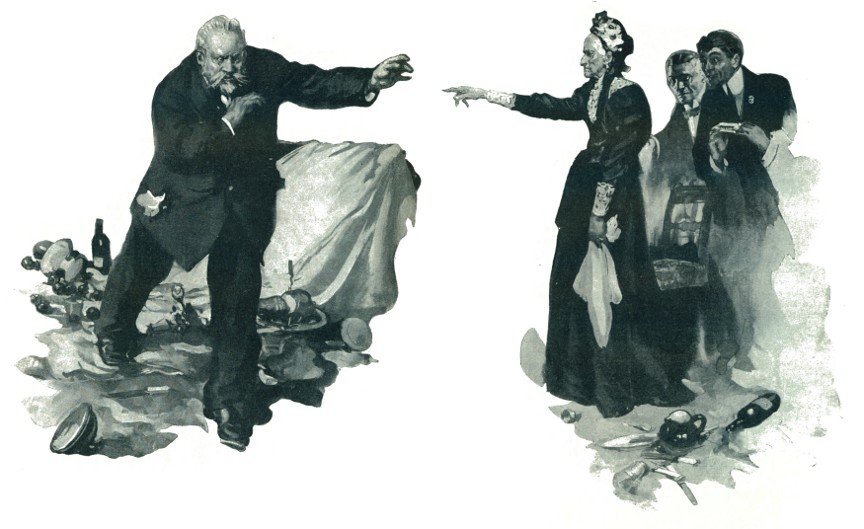

There was a strangled gasp, a clatter, and on to the table from the German’s hands there fell a little harmonica. He sat looking at it dully, and at that moment Oakes, laboriously jovial, picked the instrument up.

“I used to be able to play these things once,” he said. He put the harmonica to his lips, and began to play the opening bars of “See the conquering hero comes.” It had been his intention to explain a moment later that he was the conquering hero in question, and that what he had conquered was the problem of how Captain Gunner came to his end, for at times he was apt to indulge his sense of humour at the expense of taste; but an interruption occurred, which removed the demand for explanations.

With a clatter of crockery and a ringing of glass, the table heaved, rocked, and finally overturned, as the German, clutching it, staggered to his feet. His face was like wax, and his eyes, so dull till then, blazed with panic and horror. He threw up his hands, as if to ward something off. A choking cry came from his lips.

Oakes and Mr. Snyder were on their feet, quivering. The German had fallen back against the wall.

Mrs. Pickett’s voice rang through the room, cold and biting. She had risen from her chair.

“Captain Muller, you killed Captain Gunner!”

The German was staring straight before him, as if he saw something invisible to other eyes. He answered, mechanically, like a man in a dream: “Gott! Yes, I killed him.”

And with the last word he was on the floor, twisting and foaming. The two detectives stared at him dumbly.

“You heard, Mr. Snyder?” said Mrs. Pickett calmly. “He has confessed before witnesses.”

VIII.

“Oakes, my lad,” said Mr. Snyder, “I want just one short word with you.’’

They were sitting in Mr. Snyder’s office. Three days had elapsed since the dinner-party at the Excelsior.

“I’ve just been listening to your friend Muller’s confession, an amplified version of his brief remarks three days ago. And it seems to me that they contain food for thought. In this office a short while back you——”

“Don’t rub it in, chief,” protested Oakes.

“In this office a short while back,” proceeded Mr. Snyder ruthlessly, “you gave it as your opinion that there was no such thing as a murder without a motive. By which I take it you meant a motive which you personally would consider sufficient and satisfactory. I have it from Muller that his sole reason for killing Captain Gunner was that Captain Gunner, having a nimbler mind than himself, was accustomed to be witty at his expense. That was the basic reason. The special cause which turned his thoughts to murder was the fact that Captain Gunner, whenever he beat him at draughts—which, apparently, he did every night—used to indulge his sense of humour by playing ‘See the conquering hero comes’ on his harmonica. Not what you would call a really sufficient and satisfactory motive, eh?”

Oakes shuffled his feet.

“You also said that it was a theory of yours that, in nine cases out of ten, remarkable things don’t happen. This case strikes me as the tenth. I have been thinking over all the mistakes you made, and I can only find one point where you were right. There was a snake in the crate of bananas which came for Captain Muller from Java. It came a week before the murder, a fact which, if you had taken the trouble to find it out, would have made some difference to your reasoning. Muller killed the snake, and extracted its poison. Whether he had any idea then of using it as he afterwards did, I don’t know. He didn’t say. But he kept the poison by him, and eventually he got the idea.

“You may remember that, when you scoffed at the idea of obtaining amateur assistance from Mrs. Pickett, I told you that detection was not an exact science, but a question of common-sense and special information, and that Mrs. Pickett probably had some trivial piece of knowledge which might prove the key to the mystery. Well, she had. Captain Gunner, not wanting to keep a joke to himself, happened to have told her that, when he played ‘See the conquering hero comes’ on his harmonica, it annoyed Muller’s cat just as much as it annoyed Muller himself.

“The cat wasn’t intelligent enough to appreciate the satire, but he knew enough to know that the music of a harmonica drove him nearly mad, and he used to protest by jumping at Captain Gunner and scratching him. Captain Gunner, being a tough-skinned old fellow, didn’t mind a scratch or two, and that was what killed him.

“Muller smeared the cat’s claws with the poison, and went off to Portsmouth for the night. He knew perfectly well that, even though his departure removed one of Captain Gunner’s reasons for playing the harmonica, the odds were that he would play it for the cat’s sole benefit; and he was right.

“The chief mistake you made, Oakes, my boy, was to force facts to fit theories, instead of suiting theories to facts.

“Mrs. Pickett, your amateur friend, refusing to build on impossibilities, got at the truth, which was that the cat jumped out of the window, scratched the dog, and then sat down, as a cat would, to clean its paws. And that was the end of the cat.”

Mr. Snyder paused for breath, re-lit the cigar which, in the enjoyment of his lecture, he had allowed to go out, and resumed:

“You can look on this case, my boy, as a very valuable piece of education, which you were badly in need of. Now, I’ll just run over again, for your benefit, the list of all the mistakes you——”

Oakes interrupted him. “Take it as read, chief,” he said in a mild, conciliatory voice. “No need for more of the painful details. I get you. I’m cured.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums