Pictorial Review, October 1916

HAT do you mean—you can’t

marry him after all? After all what? Why can’t you marry him? You

are perfectly childish.”

HAT do you mean—you can’t

marry him after all? After all what? Why can’t you marry him? You

are perfectly childish.”

Lord Evenwood’s gentle voice, which had in its time lulled the House of Peers to slumber more often than any voice ever heard in the Gilded Chamber, had in it a note of unwonted, but quite justifiable, irritation. If there was one thing more than another that Lord Evenwood disliked, it was any interference with arrangements already made.

“The man,” he continued, “is not unsightly. The man is not conspicuously vulgar. The man does not eat peas with his knife. The man pronounces his aitches with meticulous care and accuracy. The man, moreover, is worth rather more than a quarter of a million pounds. I repeat, you are childish!”

“Yes, I know he’s a very decent little chap, Father,” said Lady Eva. “It’s not that at all.”

“I should be gratified, then, to hear what, in your opinion, it is.”

“Well, do you think I could be happy with him?”

Lady Kimbuck gave tongue. She was Lord Evenwood’s sister. She spent a very happy widowhood interfering in the affairs of the various branches of her family.

“We’re not asking you to be happy. You have such odd ideas of happiness. Your idea of happiness is to be married to your cousin Gerry, whose only visible means of support, so far as I can gather, is the four hundred a year which he draws as a member for a constituency which has every intention of throwing him out at the next election.”

Lady Eva blushed. Lady Kimbuck’s faculty for nosing out the secrets of her family had made her justly disliked from the Hebrides to Southern Cornwall.

“Young O’Rion is not to be thought of,” said Lord Evenwood firmly. “Not for an instant. Apart from anything else, his politics are all wrong. Moreover, you are engaged to this Mr. Bleke. It is a sacred responsibility not lightly to be evaded. You can not pledge your word one day to enter upon the most solemn contract known to—ah—the civilized world, and break it the next. It is not fair to the man. It is not fair to me. You know that all I live for is to see you comfortably settled. If I could myself do anything for you, the matter would be different. But these abominable land-taxes and Blowick—especially Blowick—no, no, it’s out of the question. You will be very sorry if you do anything foolish. I can assure you that Roland Blekes are not to be found—ah—on every bush. Men are extremely shy of marrying nowadays.”

“Especially,” said Lady Kimbuck, “into a family like ours. What with Blowick’s scandal, and that shocking business of your grandfather and the circus-woman, to say nothing of your poor father’s trouble in ’85——”

“Thank you, Sophia,” interrupted Lord Evenwood, hurriedly. “It is unnecessary to go into all that now. Suffice it that there are adequate reasons, apart from all moral obligations, why Eva should not break her word to Mr. Bleke.”

Lady Kimbuck’s encyclopedic grip of the family annals was a source of the utmost discomfort to her relatives. It was known that more than one firm of publishers had made her tempting offers for her reminiscences, and the family looked on like nervous spectators at a battle while Cupidity fought its ceaseless fight with Laziness; for the Evenwood family had at various times and in various ways stimulated the circulation of the evening papers. Most of them were living down something, and it was Lady Kimbuck’s habit, when thwarted in her lightest whim, to retire to her boudoir and announce that she was not to be disturbed as she was at last making a start on her book. Abject surrender followed on the instant.

At this point in the discussion she folded up her crochet-work, and rose.

“It is absolutely necessary for you, my dear, to make a good match, or you will all be ruined. I, of course, can always support my declining years with literary work, but——”

LADY EVA groaned. Against this last argument there was no appeal.

Lady Kimbuck patted her affectionately on the shoulder.

“There, run along now,” she said. “I daresay you’ve got a headache or something that made you say a lot of foolish things you didn’t mean. Go down to the drawing-room. I expect Mr. Bleke is waiting there to say good-night to you. I am sure he must be getting quite impatient.”

Down in the drawing-room, Roland Bleke was hoping against hope that Lady Eva’s prolonged absence might be due to the fact that she had gone to bed with a headache, and that he might escape the nightly interview which he so dreaded.

Reviewing his career, as he sat there, Roland came to the conclusion that women had the knack of affecting him with a form of temporary insanity. They temporarily changed his whole nature. They made him feel for a brief while that he was a dashing young man capable of the highest flights of love. It was only later that the reaction came and he realized that he was nothing of the sort.

At heart he was afraid of women, and in the entire list of the women of whom he had been afraid, he could not find one who had terrified him so much as Lady Eva Blyton.

Other women—notably Maraquita, now happily helping to direct the destinies of Paranoya—had frightened him by their individuality. Lady Eva frightened him both by her individuality and the atmosphere of aristocratic exclusiveness which she conveyed. He had no idea whatever of what was the proper procedure for a man engaged to the daughter of an earl. Daughters of earls had been to him till now mere names in the society columns of the morning paper. The very rules of the game were beyond him. He felt like a confirmed Association footballer suddenly called upon to play in an International Rugby match.

All along, from the very moment when—to his unbounded astonishment—she had accepted him, he had known that he was making a mistake; but he never realized it with such painful clearness as he did this evening. He was filled with a sort of blind terror. He cursed the fate which had taken him to the Charity Bazaar at which he had first come under the notice of Lady Kimbuck. The fatuous snobbishness which had made him leap at her invitation to spend a few days at Evenwood Towers he regretted; but for that he blamed himself less. Further acquaintance with Lady Kimbuck had convinced him that if she had wanted him, she would have got him somehow, whether he had accepted or refused.

What he really blamed himself for was his mad proposal. There had been no need for it. True, Lady Eva had created a riot of burning emotions in his breast from the moment they met; but he should have had the sense to realize that she was not the right mate for him, even tho he might have a quarter of a million tucked away in gilt-edged securities. Their lives could not possibly mix. He was a commonplace young man with a fondness for the pleasures of the people. He liked cheap papers, picture-palaces, and Association football. Merely to think of Association football in connection with her was enough to make the folly of his conduct clear. He ought to have been content to worship her from afar as some inaccessible goddess.

A light step outside the door made his heart stop beating.

“I’ve just looked in to say good night, Mr.—er—Roland,” she said, holding out her hand. “Do excuse me. I’ve got such a headache.”

“Oh, yes, rather; I’m awfully sorry.”

If there was one person in the world Roland despised and hated at that moment, it was himself.

“Are you going out with the guns to-morrow?” asked Lady Eva languidly.

“Oh, yes, rather! I mean no. I’m afraid I don’t shoot.”

The back of his neck began to glow. He had no illusions about himself. He was the biggest ass in Christendom.

“Perhaps you’d like to play a round of golf, then?”

“Oh, yes, rather! I mean, no.” There it was again, that awful phrase. He was certain he had not intended to utter it. She must be thinking him a perfect lunatic. “I don’t play golf.”

They stood looking at each other for a moment. It seemed to Roland that her gaze was partly contemptuous, partly pitying. He longed to tell her that, tho she had happened to pick on his weak points in the realm of sport, there were things he could do. An insane desire came upon him to babble about his school football team. Should he ask her to feel his quite respectable biceps? No.

“NEVER mind,” she said, kindly. “I daresay we shall think of something to amuse you.”

She held out her hand again. He took it in his for the briefest possible instant, painfully conscious the while that his own hand was clammy from the emotion through which he had been passing.

“Good night.”

“Good night.”

Thank Heaven, she was gone. That let him out for another twelve hours at least.

A quarter of an hour later found Roland still sitting where she had left him, his head in his hands. The groan of an overwrought soul escaped him.

“I can’t do it!”

He sprang to his feet.

“I won’t do it!”

A smooth voice from behind him spoke.

“I think you are quite right, sir—if I may make the remark.”

Roland had hardly ever been so startled in his life. In the first place, he was not aware of having uttered his thoughts aloud; in the second, he had imagined that he was alone in the room. And so, a moment before, he had been.

But the owner of the voice possessed, among other qualities, the cat-like faculty of entering a room perfectly noiselessly—a fact which had won for him, in the course of a long career in the service of the best families, the flattering position of star witness in a number of England’s raciest divorce-cases.

Mr. Teal, the butler—for it was no less a celebrity who had broken in on Roland’s reverie—was a long, thin man of a somewhat priestly cast of countenance. He lacked that air of reproving hauteur which many butlers possess, and it was for this reason that Roland had felt drawn to him during the black days of his stay at Evenwood Towers. Teal had been uncommonly nice to him on the whole. He had seemed to Roland, stricken by interviews with his host and Lady Kimbuck, the only human thing in the place.

He liked Teal. On the other hand, Teal was certainly taking a liberty. He could, if he so pleased, tell Teal to go to the deuce. Technically, he had the right to freeze Teal with a look.

He did neither of these things. He was feeling very lonely and very forlorn in a strange and depressing world, and Teal’s voice and manner were soothing.

“Hearing you speak, and seeing nobody else in the room,” went on the butler, “I thought for a moment that you were addressing me.”

This was not true, and Roland knew it was not true. Instinct told him that Teal knew that he knew it was not true; but he did not press the point.

“What do you mean—you think I am quite right?” he said. “You don’t know what I was thinking about.”

Teal smiled indulgently.

“On the contrary, sir. A child could have guessed it. You have just come to the decision—in my opinion a thoroughly sensible one—that your engagement to her ladyship can not be allowed to go on. You are quite right, sir. It won’t do.”

Personal magnetism covers a multitude of sins. Roland was perfectly well aware that he ought not to be standing here chatting over his and Lady Eva’s intimate affairs with a butler; but such was Teal’s magnetism that he was quite unable to do the right thing and tell him to mind his own business. “Teal, you forget yourself!” would have covered the situation. Roland, however, was physically incapable of saying “Teal, you forget yourself!” The bird knows all the time that he ought not to stand talking to the snake, but he is incapable of ending the conversation. Roland was conscious of a momentary wish that he was the sort of man who could tell butlers that they forgot themselves. But then that sort of man would never be in this sort of trouble. The “Teal, you forget yourself” type of man would be a first-class shot, a plus golfer, and would certainly consider himself extremely lucky to be engaged to Lady Eva.

“The question is,” went on Mr. Teal, “how are we to break it off?”

Roland felt that, as he had sinned against all the decencies in allowing the butler to discuss his affairs with him, he might just as well go the whole hog and allow the discussion to run its course. And it was an undeniable relief to talk about the infernal thing to some one.

He nodded gloomily, and committed himself. Teal resumed his remarks with the gusto of a fellow-conspirator.

“It’s not an easy thing to do gracefully, sir,

believe me, it isn’t. And it’s got to be done gracefully, or

not at all. You can’t go to her ladyship and say ‘It’s

all off, and so am I,’ and catch the next train for London. The rupture

must be of her ladyship’s making. If some fact, some disgraceful

information concerning you, were to come to her ladyship’s ears,

that would be a simple way out of the difficulty.”

“It’s not an easy thing to do gracefully, sir,

believe me, it isn’t. And it’s got to be done gracefully, or

not at all. You can’t go to her ladyship and say ‘It’s

all off, and so am I,’ and catch the next train for London. The rupture

must be of her ladyship’s making. If some fact, some disgraceful

information concerning you, were to come to her ladyship’s ears,

that would be a simple way out of the difficulty.”

He eyed Roland meditatively.

“If, for instance, you had ever been in jail, sir?”

“Well, I haven’t.”

“No offense intended, sir, I’m sure. I merely remembered that you had made a great deal of money very quickly. My experience of gentlemen who have made a great deal of money very quickly is that they have generally done their bit of time. But, of course, if you—— Let me think. Do you drink, sir?”

“No.”

Mr. Teal sighed. Roland could not help feeling that he was disappointing the old man a good deal.

“You do not, I suppose, chance to have a past?” asked Mr. Teal, not very hopefully. “I use the word in its technical sense. A deserted wife? Some poor creature you have treated shamefully?”

AT THE risk of sinking still further in the butler’s esteem, Roland was compelled to answer in the negative.

“I was afraid not,” said Mr. Teal, shaking his head. “Thinking it all over yesterday, I said to myself, ‘I’m afraid he wouldn’t have one.’ You don’t look like the sort of gentleman who had done much with his time.”

“Thinking it over?”

“Not on your account, sir,” explained Mr. Teal. “On the family’s. I disapproved of this match from the first. A man who has served a family as long as I have had the honor of serving his lordship’s, comes to entertain a high regard for the family prestige. And, with no offense to yourself, sir, this would not have done.”

“Well, it looks as if it would have to do,” said Roland, gloomily. “I can’t see any way out of it.”

“I can, sir. My niece at Aldershot.”

Mr. Teal wagged his head at him with a kind of priestly archness.

“You can not have forgotten my niece at Aldershot?”

Roland stared at him dumbly. It was like a line out of a melodrama. He feared, first for his own, then for the butler’s sanity. The latter was smiling gently, as one who sees light in a difficult situation.

“I’ve never been at Aldershot in my life.”

“For our purposes you have, sir. But I’m afraid I am puzzling you. Let me explain. I’ve got a niece over at Aldershot who isn’t much good. She’s not very particular. I am sure she would do it for a consideration.”

“Do what?”

“Be your ‘Past,’ sir. I don’t mind telling you that as a ‘Past’ she’s had some experience; looks the part, too. She’s a barmaid, and you would guess it the first time you saw her. Dyed yellow hair, sir,” he went on with enthusiasm, “done all frizzy. Just the sort of young person that a young gentleman like yourself would have had a ‘past’ with. You couldn’t find a better if you tried for a twelvemonth.”

“But, I say——!”

“I suppose a hundred wouldn’t hurt you?”

“Well, no, I suppose not, but——”

“Then put the whole thing in my hands, sir. I’ll ask leave off to-morrow and pop over and see her. I’ll arrange for her to come here the day after to see you. Leave it all to me. To-night you must write the letters.”

“Letters?”

“Naturally, there would be letters, sir. It is an inseparable feature of these cases.”

“Do you mean that I have got to write to her? But I shouldn’t know what to say. I’ve never seen her.”

“That will be quite all right, sir, if you place yourself in my hands. I will come to your room after everybody’s gone to bed, and help you write those letters. You have some note-paper with your own address on it? Then it will all be perfectly simple.”

When, some hours later, he read over the ten or twelve exceedingly passionate epistles which, with the butler’s assistance, he had succeeded in writing to Miss Maud Chilvers, Roland came to the conclusion that there must have been a time when Mr. Teal was a good deal less respectable than he appeared to be at present. Byronic was the only adjective applicable to his collaborator’s style of amatory composition. In every letter there were passages against which Roland had felt compelled to make a modest protest.

“ ‘A thousand kisses on your lovely rosebud of a mouth.’ Don’t you think that is a little too warmly colored? And ‘I am languishing for the pressure of your ivory arms about my neck and the sweep of your silken hair against my cheek!’ What I mean is—well, what about it, you know?”

“The phrases,” said Mr. Teal, not without a touch of displeasure, “to which you take exception, are taken bodily from correspondence (which I happened to have the advantage of perusing) addressed by the late Lord Evenwood to Animalcula, Queen of the High Wire at Astley’s Circus. His lordship, I may add, was considered an authority in these matters.”

Roland criticized no more. He handed over the letters, which, at Mr. Teal’s direction, he had headed with various dates, covering roughly a period of about two months antecedent to his arrival at the Towers.

“That,” Mr. Teal explained, “will make your conduct definitely unpardonable. With this woman’s kisses hot upon your lips,”—Mr. Teal was still slightly aglow with the fire of inspiration—“you have the effrontery to come here and offer yourself to her ladyship.”

With Roland’s timid suggestion that it was perhaps a mistake to overdo the atmosphere, the butler found himself unable to agree.

“You can’t make yourself out too bad. If you don’t pitch it hot and strong, her ladyship might quite likely forgive you. Then where would you be?”

Miss Maud Chilvers, of Aldershot, burst into Roland’s life like one of the shells of her native heath two days later at about five in the afternoon.

It was an entrance of which any stage-manager might have been proud of having arranged. The lighting, the grouping, the lead-up—all were perfect. The family had just finished tea in the long drawing-room. Lady Kimbuck was crocheting, Lord Evenwood dozing, Lady Eva reading, and Roland thinking. A peaceful scene.

A soft, rippling murmur, scarcely to be reckoned a snore, had just proceeded from Lord Evenwood’s parted lips, when the door opened, and Teal announced,

“Miss Chilvers.”

Roland stiffened in his chair. Now that the ghastly moment had come, he felt too petrified with fear even to act the little part in which he had been diligently rehearsed by the obliging Mr. Teal. He simply sat and did nothing.

It was speedily made clear to him that Miss Chilvers would do all the actual doing that was necessary. The butler had drawn no false picture of her personal appearance. Dyed yellow hair done all frizzy was but one fact of her many-sided impossibilities. In the serene surroundings of the long drawing-room, she looked more unspeakably “not much good” than Roland had ever imagined her. With such a leading lady, his drama could not fail of success. He should have been pleased; he was merely appalled. The thing might have a happy ending, but while it lasted it was going to be terrible.

She had a flatteringly attentive reception. Nobody failed to notice her. Lord Evenwood woke with a start, and stared at her as if she had been some ghost from his trouble of ’85. Lady Eva’s face expressed sheer amazement. Lady Kimbuck, laying down her crochet-work, took one look at the apparition, and instantly decided that one of her numerous erring relatives had been at it again. Of all the persons in the room, she was possibly the only one completely cheerful. She was used to these situations and enjoyed them. Her mind, roaming into the past, recalled the night when her cousin Warminster had been pinked by a stiletto in his own drawing-room by a lady from South America. Happy days, happy days.

Lord Evenwood had, by this time, come to the conclusion that the festive Blowick must be responsible for this visitation. He rose with dignity.

“To what are we——?” he began.

Miss Chilvers, resolute young woman, had no intention of standing there while other people talked. She shook her gleaming head and burst into speech.

“Oh, yes, I know I’ve no right to be coming walking in here among a lot of perfect strangers at their teas, but what I say is, ‘Right’s right and wrong’s wrong all the world over,’ and I may be poor, but I have my feelings. No, thank you, I won’t sit down. I’ve not come for the weekend. I’ve come to say a few words, and when I’ve said them I’ll go, and not before. A lady friend of mine happened to be reading her Daily Sketch the other day, and she said ‘Hullo! hullo!’ and passed it on to me with her thumb on a picture which had under it that it was Lady Eva Blyton who was engaged to be married to Mr. Roland Bleke. And when I read that, I said ‘Hullo! hullo!’ too, I give you my word. And not being able to travel at once, owing to being prostrated with the shock, I came along to-day, just to have a look at Mr. Roland Blooming Bleke, and ask him if he’s forgotten that he happens to be engaged to me. That’s all. I know it’s the sort of thing that might slip any gentleman’s mind, but I thought it might be worth mentioning. So now!”

ROLAND, perspiring in the shadows at the far end of the room, felt that Miss Chilvers was overdoing it. There was no earthly need for all this sort of thing. Just a simple announcement of the engagement would have been quite sufficient. It was too obvious to him that his ally was thoroughly enjoying herself. She had the center of the stage, and did not intend lightly to relinquish it.

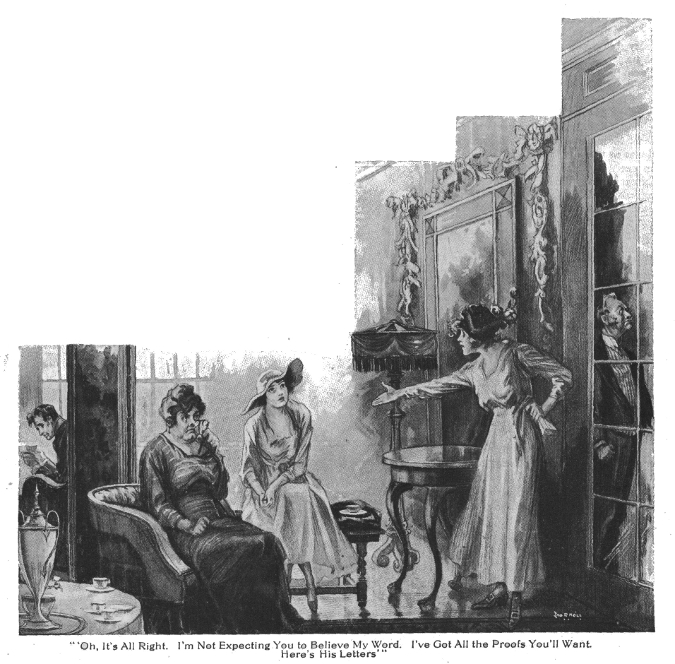

“My good girl,” said Lady Kimbuck, “talk less and prove more. When did Mr. Bleke promise to marry you?”

“Oh, it’s all right. I’m not expecting you to believe my word. I’ve got all the proofs you’ll want. Here’s his letters.”

Lady Kimbuck’s eyes gleamed. She took the package

eagerly. She never lost an opportunity of reading compromising letters.

She enjoyed them as literature, and there was never any knowing when they

might come in useful.

Lady Kimbuck’s eyes gleamed. She took the package

eagerly. She never lost an opportunity of reading compromising letters.

She enjoyed them as literature, and there was never any knowing when they

might come in useful.

“Roland,” said Lady Eva, quietly, “haven’t you anything to contribute to this conversation?”

Miss Chilvers clutched at her bodice. Cinema palaces were a passion with her, and she was up in the correct business.

“Is he here? In this room?”

Roland slunk from the shadows.

“Mr. Bleke,” said Lord Evenwood, sternly, “who is this woman?”

Roland uttered a kind of strangled cough.

“Are these letters in your handwriting?” asked Lady Kimbuck, almost cordially. She had seldom read better compromising letters in her life, and she was agreeably surprized that one whom she had always imagined a colorless stick should have been capable of them.

Roland nodded.

“Well, it’s lucky you’re rich,” said Lady Kimbuck philosophically. “What are you asking for these?” she enquired of Miss Chilvers.

“Exactly,” said Lord Evenwood, relieved. “Precisely. Your sterling common sense is admirable, Sophia. You place the whole matter at once on a businesslike footing.”

“Do you imagine for a moment——?” began Miss Chilvers slowly.

“Yes,” said Lady Kimbuck, “How much?”

Miss Chilvers sobbed.

“If I have lost him for ever——”

Lady Eva rose.

“But you haven’t,” she said pleasantly. “I wouldn’t dream of standing in your way.” She drew a ring from her finger, placed it on the table, and walked to the door. “I am not engaged to Mr. Bleke,” she said, as she reached it.

Roland never knew quite how he had got away from The Towers. He had confused memories in which the principals of the drawing-room scene figured in various ways, all unpleasant. It was a portion of his life on which he did not care to dwell.

Safely back in his flat, however, he gradually recovered his normal spirits. Indeed, now that the tumult and the shouting had, so to speak, died, and he was free to take a broad view of his position, he felt distinctly happier than usual. That Lady Kimbuck had passed for ever from his life was enough in itself to make for gaiety.

HE WAS humming blithely one morning as he opened his letters; outside the sky was blue and the sun shining. It was good to be alive. He opened the first letter. The sky was still blue, the sun still shining.

“Dear Sir,” (it ran).

“We have been instructed by our client, Miss Maud Chilvers, of the Goat and Compasses, Aldershot, to institute proceedings against you for Breach of Promise of Marriage. In the event of your being desirous to avoid the expense and publicity of litigation, we are instructed to say that Miss Chilvers would be prepared to accept the sum of ten thousand pounds in settlement of her claim against you. We would further add that in support of her case our client has in her possession a number of letters written by yourself to her, all of which bear strong prima facie evidence of the alleged promise to marry: and she will be able in addition to call as witnesses in support of her case the Earl of Evenwood, Lady Kimbuck, and Lady Eva Blyton, in whose presence, at a recent date, you acknowledged that you had promised to marry our client.

“Trusting that we hear from you in the course of post.

We are, dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

Harrison, Harrison, Harrison, & Harrison.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums