Pictorial Review, March 1912

I WANT to tell you about dear old Freddie Meadowes. I’m a little shy on literary style and all that; but I’ll have some writer fellow fix the thing when I’m through, so that’ll be all right.

Dear old Freddie, don’t you know, has been a dear old pal of mine for years and years; so when I went into the club one morning and found him sitting alone in a dark corner, staring glassily at nothing and looking generally like the last run of shad, you can understand I was quite disturbed about it. As a rule, the old lobster is the life and soul of our set—quite the little ray of sunshine.

Jimmy Pinkerton was with me at the time. Jimmy’s a fellow who writes plays, a deuced brainy sort of fellow. My name’s Pepper, by the way, Reggie Pepper. My uncle, Edward Sigsbee Pepper, was Pepper’s Safety Razor. When he died he left me a sizable wad. Well, as I was saying, Jimmy was with me, and between us we set to work to question the poor, pop-eyed boy, until finally we got at what the matter was.

As we might have guessed, it was a girl. He had had a quarrel with Angela West, the girl he was engaged to, and she had called off the engagement. What the fuss had been about, he didn’t say; but she had it in bad for him all right. She wouldn’t let him come near her, refused to talk on the ’phone, and sent back his letters unopened.

I was sorry for poor old Freddie. It’s a tough moment in a man’s life when he realizes that he has been feeding a girl candy and American Beauties for weeks all for nothing. I knew what it felt like. I was once in love myself, with a girl called Kathryn Mae Shoolbred, and the fact that she turned me down cold will be recorded in my autobiography. I knew the dope for Freddie.

“Change of scene is what you want, old scout,” I said. “Come with me to Pine Beach. I’ve taken a cottage there. Jimmy’s coming down on the twenty-fourth. We’ll be a cozy party.”

“Sure,” said Jimmy. “Change of scene’s the thing. I knew a man. Girl turned him down. Man went abroad. Two months later girl cabled him, ‘Come back. Muriel.’ Man started to write out a cable; suddenly found that he couldn’t remember girl’s surname; so never answered at all.”

But Freddie wouldn’t be comforted. He just went on looking as if he had swallowed his last nickel. However, I got him to promise to come to Pine Beach with me. He said he might as well be there as anywhere.

Do you know Pine Beach? It isn’t what you’d call a fiercely exciting spot, but it has its good points. You spend the day there bathing, and sitting on the sands, and in the evening you stroll out on the shore with the mosquitos. At nine o’clock you rub witch-hazel on the wounds and go to bed. It’s that sort of place.

It seemed to suit poor old Freddie. Once the moon was up and the breeze sighing in the pines, you couldn’t drag him from that beach with a rope. He became quite a popular pet with the mosquitos. They’d hang around waiting for him to come out and would turn down perfectly good strollers, just so as to be in shape for him.

Yes, it was a peaceful sort of life; but by the end of the first week I began to wish that Jimmy Pinkerton had arranged to come down earlier. As a companion, Freddie, poor old chap, wasn’t anything to write home to Mother about. When he wasn’t chewing a pipe and scowling at the carpet, he was sitting at the piano, playing “The Rosary” with one finger. He couldn’t play anything except “The Rosary,” and he couldn’t play much of that. Somewhere around the third bar a fuse would blow out, and he’d have to start all over again. I was fond of the old boy, but by the end of the week I was beginning to feel that I had heard the tune before.

He was playing it, as usual, one morning when I came in from bathing. I gave him a reproachful sort of a look, don’t you know; for, honestly, no fellow, even if he had been turned down by a hundred girls, had any right to be indoors on a day like that. It was one of those great mornings. The sun was shining; there was a cool breeze, and all along the beach you could hear the happy laughter of little children who had been told not to get their feet wet but found themselves up to the neck in rock-pools.

“Reggie,” he said in a hollow voice, looking up, “I’ve seen her.”

“Seen her?” I said. “What, Miss West?”

“I was down at the post-office getting the mail, and we met in the doorway. She cut me!”

He started “The Rosary” again, and side-slipped in the second bar.

“Reggie,” he said, “you ought never to have brought me here.”

“How was I to know she was coming here?”

“I must go away,” he said.

I wouldn’t stand for this.

“Go away?” I said. “Don’t be a quitter! This is the best thing that could have happened. This is where you make your by-play.”

“She cut me!”

“Never mind. Be a sport. Take another whirl at her.”

“She looked clean through me!”

“Sure she did. But don’t mind that. Put this thing in my hands. I’ll see you through. Now what you want,” I said, “is to place her under some obligation to you. What you want is to get her timidly thanking you. What you want——”

“But what’s she going to thank me timidly for?”

I thought for a moment.

“Watch out for a chance and save her from drowning,” I suggested.

“I can’t swim,” said Freddie.

That was Freddie all over, don’t you know—a dear old chap in a thousand ways, but no help to a fellow, if you know what I mean.

He cranked up the piano once more and I beat it for the open. I strolled out onto the seashore and began to think this thing over. There was no doubt that the brain-work had got to be done by me. Dear old Freddie had his strong qualities. He was corking at polo, and in happier days could imitate cats scrapping in a back yard better than any fellow I have ever met. But aside from that, he wasn’t a man of enterprise. No, it was up to me. What he wanted was a helping hand, and I made up my mind that I would give it to him.

Well, don’t you know, I was rounding some rocks, with my brain whirring like a dynamo, when I caught sight of a blue dress, and, by George, it was the girl. I had never met her; but Freddie had sixteen photographs of her sprinkled around his bedroom, and I knew I couldn’t be mistaken. She was sitting on the sand, helping a small, fat child build a castle. On a chair nearby was an elderly lady reading a novel. I heard the girl call her “Aunt.” So, pulling the Sherlock P. Holmes stuff, I deduced that the fat child was her cousin. It struck me that if Freddie had been there he would probably have tried to work up some punk sentiment about the kid on the strength of it. Personally, I couldn’t manage it. I don’t think that I ever saw a child who made me feel less sentimental. He was one of those round, bulging kids.

After he had finished the castle, he seemed to get bored with life and began to whimper. The girl took him off to where a fellow was selling candy at a stall. I walked on.

Now fellows, if you ask them, will tell you that I’m a chump. Well, I’m not kicking. I admit it. I am a chump. All the Peppers have been chumps. But what I do say is that every now and then, when you’d least expect it, I line out a regular three-bagger brain-wave, and that’s what happened now. I doubt if the idea that came to me then would have occurred to a single one of any dozen high-brows you care to name. Napoleon might have thought of it, but nobody else. And I’m not so sure about Napoleon.

It came to me on my return journey. I was walking back along the shore, when I saw the fat kid meditatively smacking a jellyfish with a spade. The girl wasn’t with him. In fact, there didn’t seem to be any one in sight. I was just going to pass on, when I got the brain-wave. I thought the whole thing out in a flash, don’t you know. From what I had seen of the two, the girl was evidently fond of this kid, and, anyway, he was her cousin. So what I said to myself was this, “If I kidnap this young heavyweight for the moment, and if, when the girl has got all worked up about where he can have got to, dear old Freddie suddenly appears, leading the infant by the hand and pulling a story to the effect that he has found him wandering at large about the country and practically saved his life, why, the girl’s gratitude is bound to make her can the rough stuff and be friends again.” So I gathered in the kid and made off with him. All the way home I pictured that scene of reconciliation. I could see it so vividly, don’t you know, that, by George, it gave me quite a choky feeling in my throat.

Freddie, dear old chap, was rather slow at getting on to the fine points of the idea. When I appeared, carrying the kid, and dumped him down in our sitting-room, he didn’t absolutely effervesce with joy, if you know what I mean. The kid had started in to bellow by this time, and poor old Freddie seemed to find it rather trying.

“Cut it out!” he said. “Do you think nobody’s got any trouble except you? What the deuce is all this, Reggie? Where did you pick up that?”

The kid came back at him with yell that made the window rattle. I raced to the kitchen and fetched a jar of honey. It was the right dope. The kid quit bellowing and began to smear his face with the stuff. Most interesting it was to watch!

“Well?” said Freddie, when silence had set in.

I explained the idea. After a while it began to strike him.

“You’re not such a chump as you look, sometimes, Reggie,” he said handsomely. “I’m bound to say this looks pretty good.”

He disentangled the kid from the honey jar and took him out to scour the beach for Angela. I don’t know when I’ve felt so happy. I was so fond of dear old Freddie that to know that he was so soon going to be his old bright self again made me feel as if somebody had left me about a million. I was leaning back in a chair on the porch, smoking peacefully, when down the road I saw the old boy returning, and, by George, the kid was still with him. And Freddie looked as if he hadn’t a friend in the world.

“Hello,” I said. “Couldn’t you find her?”

“Yes, I found her,” he replied, with one of those bitter, hollow laughs.

“Well, then——?”

Freddie sunk into a chair and groaned.

“This isn’t her cousin, you bonehead,” he said. “He’s no relation at all. He’s just a kid she happened to meet on the beach. She had never seen him before in her life.”

“What! Who is he then?”

“I don’t know. Oh, Lord, I’ve had a time! Thank goodness you’ll probably spend the next few years of your life in Sing Sing for kidnapping. That’s my only consolation. I’ll come and josh you through the bars, by George! No, I won’t, though; I shall be dead before that.”

“Tell me all, old scout,” I said. “There seems to have been some trifling unpleasantness.”

It took him a good long time to tell the story, for he

broke off in the middle of nearly every sentence to call me names; but

I gathered gradually what had happened.

It took him a good long time to tell the story, for he

broke off in the middle of nearly every sentence to call me names; but

I gathered gradually what had happened.

She had listened like an iceberg while he spoke the piece he had prepared, and then—well, she didn’t actually call him a liar, but she gave him to understand in a general sort of way that, if he and old Doctor Cook ever happened to meet, and got to swapping stories, it would be about the toughest duel on record. And then he had crawled away with the kid, licked to a splinter.

“And mind, it’s up to you,” he concluded. “I’m not mixed up in this thing at all. If you want to escape your sentence, you’d better get busy and find the kid’s parents and return him before the cops come for you. It’s got nothing to do with me. I’m not your accomplice.”

He went in, and I heard him swatting the piano like a lost soul.

BY George, you know, till I started to tramp the seashore with this infernal kid, I never had a notion it would have been so deuced difficult to restore a child to its anxious parents. It’s a mystery to me how kidnappers ever get caught. I went through Pine Beach with a fine tooth comb; but nobody came forward to claim the infant. You’d have thought, from the lack of interest in him, that he was stopping there all by himself in a cottage of his own. It wasn’t till, by an inspiration, I thought to ask the candy man, that I found out that his name was Medwin and that his parents lived at a place called “Ocean Rest” in Beach Road.

I shot off there like an arrow, and knocked at the door. Nobody answered. I knocked again. I could hear movements inside; but nobody came. I was just going to get so busy with that knocker that the idea would filter through into those people’s heads that I wasn’t standing there just for the fun of the thing, when a voice from somewhere above shouted, “Hi!”

You know a fellow has to be in the mood to enjoy that sort of thing. I wasn’t. I looked up and saw a round, pink face, with gray whiskers east and west of it, staring down from an upper window.

“Hi!” it shouted again.

“What the deuce do you mean by ‘Hi!’?” I asked.

“You can’t come in,” said the face. “Hello, is that Tootles?”

“My name is not Tootles, and I don’t want to come in,” I said. “Are you Mr. Medwin? I’ve brought back your son.”

“I see him. Peep-bo, Tootles! Poppa can see ’oo!” The face disappeared with a jerk. I could hear the sound of voices. The face reappeared.

“Hi!”

I churned the gravel madly.

“Do you live here?” said the face.

“I’m staying here for a few weeks.”

“What’s your name?”

“Pepper. But——”

“Pepper? Any relation to Sigsbee Pepper?”

“My uncle. But——”

“We were at school together. Dear old Sigsbee Pepper! I wish I were with him now.”

“I wish you were,” I said.

He beamed down at me.

“This is most fortunate,” he said. “We were wondering what we were to do with Tootles. You see we have the mumps here. My daughter Bootles has just developed mumps. Tootles must not be exposed to the risk of infection. We could not think what we were to do with him. It was most fortunate your finding him. He strayed from his nurse. I would hesitate to trust him to the care of a stranger; but you are different. Any nephew of Sigsbee Pepper’s has my implicit confidence. You must take Tootles to your house. It will be an ideal arrangement. I have written to my brother in Pittsburg to come and fetch him. He may be here in a few days.”

“May!”

“He is a busy man, of course, but he should certainly be here within a week. Till then Tootles can stop with you. It is an excellent plan. Very much obliged to you. Your wife will like Tootles.”

“I haven’t got a wife,” I yelled; but the window had closed with a bang, as if the man with the whiskers had found a germ trying to escape, don’t you know, and had headed it off just in time.

I breathed a deep breath and wiped my forehead.

The window flew up again.

“Hi!”

A package weighing about a ton hit me on the head and burst like a bomb.

“Did you catch it?” said the face, reappearing. “Dear me, you missed it! Never mind. You can get it at the store. Ask for Bailey’s Granulated Breakfast Chips. Tootles takes them for breakfast with a little cream. Be sure to get Bailey’s. Good morning.”

My spirit was broken, if you know what I mean. I accepted the situation. Taking Tootles by the hand, I walked slowly away, the iron neatly inserted in my soul. Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow was a picnic by the side of it.

As we turned up the road, we met Freddie’s Angela.

The sight of her had a marked effect on the kid Tootles. He pointed at

her and said, “Wah!”

As we turned up the road, we met Freddie’s Angela.

The sight of her had a marked effect on the kid Tootles. He pointed at

her and said, “Wah!”

The girl stopped and smiled. I loosed the kid and he ran to her.

“Hello, baby,” she said, bending down to him. “So Father found you again, did he? Your little son and I made friends on the beach this morning,” she said to me.

This was the limit. Coming on top of that interview with the whiskered lunatic, it so utterly unnerved me, don’t you know, that she had nodded good-by and was half-way down the road before I caught up with my breath enough to deny the charge of being the infant’s father. However, it was only one more drop in the bitter cup. I fed the kid peanut clusters to quiet him, and went back to the cottage.

I hadn’t expected dear old Freddie to sing with joy when he found out what had happened, but I did think he might have shown a little more manly fortitude. He leaped up, glared at the kid, and clutched his head. He didn’t speak for a long time. On the other hand, when he began, he did not leave off for a long time. The dear old boy certainly produced some harsh words during that session.

“Well,” he said, when he had finished. “Say something! Heavens, man, why don’t you say something?”

“You don’t give me a chance, old top,” I said.

“What are you going to do about it?”

“What can we do about it?”

“We can’t spend our time acting as nurses to this—this exhibit.”

He got up.

“I’m going back to New York,” he said.

“Freddie!” I cried. “Freddie, old rox!” My voice shook. “You wouldn’t desert a pal at a time like this?

“I would. This is your business and you’ve got to manage it.”

“Freddie,” I said, “you’ve got to stand by me. You must. Do you realize that this child has to be undressed and bathed and dressed again? You wouldn’t leave me to tackle a proposition like that single-handed? Freddie, old scout, watch me! I’m giving you the distress sign we used to have in the frat.”

He sat down again.

“Oh, well,” he said resignedly.

“Besides, old top,” I said, “I did it all for your sake, don’t you know.”

He looked at me in a curious way.

“Reggie,” he said in a strained voice, “one moment. I’ll stand for a good deal, but I won’t stand for being expected to be grateful. Remember that, you infernal Happy Hooligan!”

LOOKING back at it, I see that what saved me from Matteawan in that crisis was my bright idea of buying up most of the contents of the local candy shop. By feeding the kid peanut clusters practically incessantly, we managed to get through the rest of that day pretty satisfactorily. At eight o’clock he fell asleep in a chair, and, having undressed him by unbuttoning every button in sight, and where there were no buttons pulling till something gave, we carried him up to bed.

Freddie stood looking at the pile of clothes on the floor,

and I knew what he was thinking. To get the kid undressed had been simple—a

mere matter of muscle. But how were we to get him into his clothes again?

I stirred the pile with my foot. There was a long linen arrangement which

might have been anything, also a strip of pink flannel which was like nothing

on earth. We looked at each other and smiled wanly.

Freddie stood looking at the pile of clothes on the floor,

and I knew what he was thinking. To get the kid undressed had been simple—a

mere matter of muscle. But how were we to get him into his clothes again?

I stirred the pile with my foot. There was a long linen arrangement which

might have been anything, also a strip of pink flannel which was like nothing

on earth. We looked at each other and smiled wanly.

In the morning I remembered that there were children at the next bungalow but one. We went there before breakfast and borrowed their nurse. Women are wonderful; by George, they are! She had that kid dressed and looking fit for anything in about eight minutes. I showered wealth on her, and she promised to come in morning and evening. I sat down to breakfast feeling almost cheerful again. It was the first bit of silver lining there had been to the cloud up to date.

“And after all,” I said, “there’s lots to be said for having a child about the house. Kind of cozy and domestic, what?”

Just then the kid upset the cream over Freddie’s trousers. When he had come back after changing his clothes, he began to talk about what a much maligned man King Herod was. The more he saw of Tootles, he said, the less he wondered at those impulsive views of his on infanticide.

Two days later Jimmy Pinkerton came down. Jimmy took one look at Tootles, who happened to be howling at the moment, and picked up his grip.

“The hotel,” he said, “for me. I can’t write dialogue with that sort of thing going on. Whose work is this? Which of you adopted this little treasure?”

I told him about Mr. Medwin and the mumps. Jimmy seemed interested.

“I might work this up for the stage,” he said. “It wouldn’t make a bad situation for Act Two of a farce.”

“Farce!” snarled poor old Freddie.

“Sure. Curtain of Act One on hero, a half-baked sort of idiot just like—that is to say, a half-baked sort of idiot kidnapping the child. Second Act, his adventures with it. I’ll rough it out to-night. Come along and show me the hotel, Reggie.”

As we went, I told him the rest of the story, the Angela part. He laid down his grip and looked at me like an owl through his glasses.

“What!” he said. “Why, hang it, this is a play, ready-made. It’s the old ‘Tiny Hand’ business. Always safe stuff. Parted lovers. Lisping child. Reconciliation over the little cradle. It’s big. Child, center. Girl, l. c. Freddie, up stage, by the piano. Can Freddie play the piano?”

“He can play a little of ‘The Rosary’ with one finger.”

Jimmy shook his head.

“No, we shall have to cut out the soft music. But the rest goes. See here.” He squatted in the sand. “This stone is the girl. This chunk of seaweed’s the child. This peanut shell is Freddie. Dialogue leading up to child’s line. Child speaks like: ‘Boofer lady, does ’oo love dadda?’ Business of outstretched hands. Hold picture for a moment. Freddie crosses l., takes girl’s hand. Business of swallowing lump in throat. Then big speech. ‘Ah, Marie,’ or whatever her name is—Jane—Agnes—Angela? Very well. ‘Ah, Angela, has not this gone on too long? A little child rebukes us! Angela!’ And so on. Freddie must work up his own part. I’m just giving you the general outline. And we must get a good line for the child. ‘Boofer lady, does ’oo love dadda?’ isn’t definite enough. We want something more—ah! ‘Kiss Freddie;’ that’s it. Short, crisp and has the punch.”

“But, Jimmy, old top,” I said, “the only objection is, don’t you know, that there’s no way of getting the girl to the cottage. She cuts Freddie. She wouldn’t come within a mile of him or the house where he lives.”

Jimmy frowned.

“That’s awkward,” he said. “Well, we shall have to make it an exterior set instead of an interior. We can easily corner her on the beach somewhere, when we’re ready. Meanwhile, we must get the kid letter-perfect. First rehearsal for lines and business eleven sharp tomorrow.”

Poor old Freddie was in such a gloomy state of mind that we decided not to tell him the idea till we were through with coaching the kid. He wasn’t in the mood to have a thing like that hanging over him. So we concentrated on Tootles. And pretty early in the proceedings we got next to the fact that the only way to get Tootles worked up to the spirit of the thing was to introduce peanut clusters as a submotive, so to speak.

“The chief difficulty,” said Jimmy Pinkerton, at the end of the first rehearsal, “is to establish a connection in the kid’s mind between his line and the candy. Once he has grasped the basic fact that those two words, clearly spoken, result automatically in peanut clusters, we have got a success.”

I’ve often thought, don’t you know, how interesting it must be to be one of those animal trainer Johnnies; to stimulate the dawning intelligence, and that sort of thing. Well, this was every bit as exciting. Some days success seemed to be staring us in the eye, and the kid got the line out as if he’d been the star in a Broadway production. And then he’d go all to pieces again. And time was flying.

“We must get a move on, Jimmy,” I said. “The kid’s uncle may arrive any day now and swipe our star.”

“And we haven’t an understudy,” said Jimmy. “There’s something in that. We must hustle. Gee, that kid’s a bad study. I’ve known deaf-mutes who would have learned the part quicker.”

I will say this for the kid, though, he was no quitter. Failure didn’t discourage him. Whenever he saw a peanut cluster now, he had a dash at his line and kept on saying something till he got the candy. His only fault was his uncertainty. Personally, I would have been prepared to take a chance on him and start the performance at the first opportunity; but Jimmy said no.

“We’re not nearly ready,” said Jimmy. “To-day, for instance, he said ‘Kick Fweddie.’ That’s not going to win any girl’s heart. And she might do it, too. No, we must postpone production a while yet.”

But, by George, we didn’t. The curtain went up the very next afternoon.

It was nobody’s fault—certainly not mine. It was just Fate. Freddie had settled down at the piano, and I was leading the kid out of the house to exercise it, when just as we’d got out onto the porch, along came the girl Angela on her way to the beach. The kid set up his usual yell at the sight of her, and she stopped at the foot of the steps.

“Hello, baby,” she said. “Good morning,” she said to me. “May I come up?”

She didn’t wait for an answer. She just came. She seemed to be that sort of girl. She came up on the porch and started fussing over the kid. And six feet away, mind you, Freddie mixing it with the piano in the sitting-room! It was a dashed disturbing situation, don’t you know. At any minute Freddie might take it into his head to come out onto the porch, and we hadn’t even begun to rehearse him in his part.

I tried to break up the scene.

“We were just going down to the beach,” I said.

“Yes?” said the girl. She listened for a moment. “So you’re having your piano tuned,” she said. “My aunt has been trying to find a tuner for ours. Do you mind if I go in and tell this man to come on to us when he’s finished here?”

“Er—not yet,” I said. “Not yet, if you don’t mind. He can’t bear to be disturbed when he’s working. It’s the artistic temperament. I’ll tell him later.”

“Very well,” she said, getting up to go. “Ask him to call at Pine Bungalow. West is the name. Oh, he seems to have stopped. I suppose he will be out in a minute now. I’ll wait.”

“Don’t you think—shouldn’t we be going to the beach?” I said.

She had started talking to the kid and didn’t hear. She was feeling in her pocket for something.

“The beach,” I babbled.

“See what I’ve brought for you, baby,” she said. And, by George, don’t you know, she held up in front of the kid’s bulging eyes a chunk of candy about the size of the Metropolitan Tower.

That finished it. We had just been having a long rehearsal, and the kid was all worked up in his part. He got it right the first time.

“Kiss Fweddie!” he shouted.

The front door opened, and Freddie came out onto the porch, for all the world as if he had been taking a cue.

He looked at the girl, and the girl looked at him. I looked at the ground, and the kid looked at the candy.

“Kiss Fweddie!” he yelled. “Kiss Fweddie!”

The girl was still holding up the candy, and the kid did what Jimmy Pinkerton would have called “business of outstretched hands” towards it.

“Kiss Fweddie!” he shrieked.

“What does this mean?” said the girl, turning to me.

“You’d better give it him, don’t you know,” I said. “He’ll go on till you do.”

She gave the kid his candy, and he subsided. Poor old Freddie still stood there gaping, without a word.

“What does it mean?” said the girl again. Her face was pink, and her eyes were sparkling in the sort of way, don’t you know, that makes a fellow feel as if he hadn’t any bones in him.

“Well?” she said, and her teeth gave a little click.

I gulped. Then I said it was nothing. Then I said it was

nothing much. Then I said, “Oh, well, it was this way.” And,

after a few pithy remarks about Jimmy Pinkerton, I told her all about it.

And, all the while, Bonehead Freddie stood there gaping, without a word.

I gulped. Then I said it was nothing. Then I said it was

nothing much. Then I said, “Oh, well, it was this way.” And,

after a few pithy remarks about Jimmy Pinkerton, I told her all about it.

And, all the while, Bonehead Freddie stood there gaping, without a word.

And the girl didn’t speak either. She just stood listening.

And then she began to laugh. I never heard a girl laugh so much. She leaned against the pillar of the porch and shrieked. And all the while Freddie, the World’s Champion Chump, stood there, saying nothing.

Well, I sidled towards the steps. I had spoken my piece, and it seemed to me that just here the stage direction “exit” was written in my part.

Just out of sight of the house I met Jimmy Pinkerton.

“Hello, Reggie,” he said. “I was just coming to you. Where’s the kid? We must have a big rehearsal to-day.”

“No good,” I said sadly. “It’s all over. The thing’s finished. Poor dear old Freddie has made an ass of himself and killed the whole show.”

“Tell me,” said Jimmy.

I told him what had happened.

“Fluffed in his lines, did he?” said Jimmy, nodding thoughtfully. “It’s always the way with these amateurs. We must go back at once. Things look bad; but it may not be too late,” he said as we started. “Even now a few well-chosen words from a man of the world, and——”

“Great Scott!” I cried. “Look!”

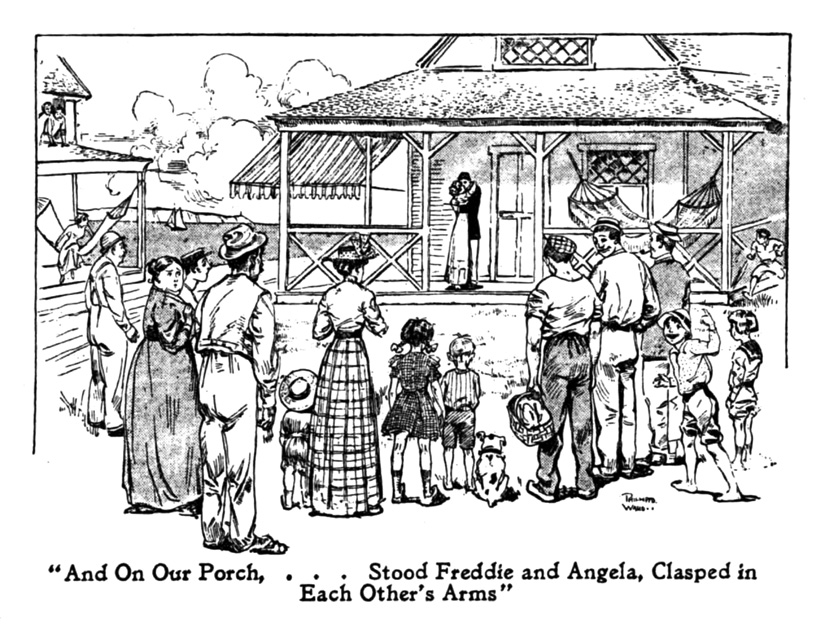

In front of the cottage stood six children, a nurse and the fellow from the grocery store, rubbering. From the windows of the houses opposite projected about four hundred heads of both sexes, rubbering. Down the road came galloping five more children, a dog, three men and a boy, about to rubber. And on our porch, as unconscious of the spectators as it they had been alone in the Sahara, stood Freddie and Angela, clasped in each other’s arms.

Editor’s Note:

Thanks to Tony Ring for providing a copy

of this item, and to Neil Midkiff for cleaning up the graphics.

Compare this American text with the British version from the Strand magazine. The story was revised in 1926 as “Fixing It for Freddie” starring Bertie Wooster in Carry On, Jeeves and in 1959 as “Unpleasantness at Kozy Kot” in A Few Quick Ones starring other Drones.

Sherlock P. Holmes: See the annotations to Money for Nothing.

old rox: See endnote to “Disentangling Old Duggie” for more on this obscure slang term.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums