Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture, June 1901

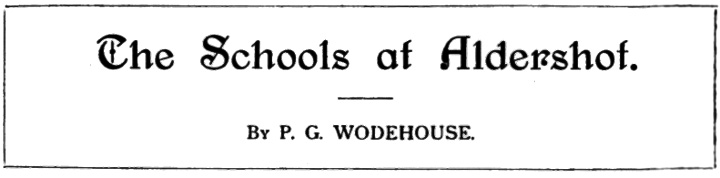

OF all inter-school contests the annual Boxing, Fencing, and Gymnastic Competition, held at Aldershot in the last days of March or the first days of April, is, with the possible exception of the Ashburton Shield Meeting, the most important and representative. Forty or more schools compete in gymnastics, and about twenty in the fencing and sabres. The boxing usually claims between thirty-five and forty entries, most schools sending up more than one representative. There are four classes—feather-weights, not exceeding 9 st.; light-weights, anything up to 10 st.; middles, 11 st. 4 lb. and under; and heavies, any weight. With the exception of St. Paul’s, who generally enter a man for each weight, most of the schools limit themselves to two champions, usually in two of the lighter weights. The heavy-weight medals are sometimes contested for by only two pairs of fighters.

Early in February a circular is sent round to the various schools, in which are set forth the rules and date of the competition. With the circular come entry forms, to be filled in and returned, together with certain fees, about a fortnight before the appointed date. The competition is usually held at the Queen’s Road Gymnasium, as being the roomiest of the Aldershot Army gymnasiums. It commences at noon, but the majority of the competitors put in an appearance shortly after half-past ten, some from hotels where they have been spending the night, others straight from their respective schools. There is always a small, but interested, crowd round the doors of the Gymnasium to watch the competitors go in.

On entering the building these make for the dressing-room—a long room, along one side of which are ranged benches, along the other, seats. The door is draped with a Union Jack.

It is here that the boxers get their first chance of seeing their opponents “buffed.” It is a well-known fact that an athlete always looks his largest under such conditions; and A, a light-weight, eyeing B, a middle-weight, furtively, as he changes on his right hand, wonders if he is one of his opponents, and, if so, how on earth he can weigh only 10 st. with a chest and biceps like that. On his left, C, a feather-weight, is examining A with equal care and misgivings.

At eleven o’clock all doubts are cleared up definitely. “Will all those who are entering for the boxing competitions get ready for weighing,” shouts an official. In another ten minutes the weighing-in is in full swing, each weight as it is taken being carefully compared with the weight given on the entry forms a fortnight before. The laws of the competition are drastic in the extreme. Whoever misses the weighing-in also misses the rest of the day’s programme, unless he cares to stay on as a spectator.

The gymnasts in the meantime have donned their war-paint and entered the arena, with many critical looks at one another and perhaps a little nervousness, for a gymnast can never get rid entirely of the nightmare feeling that his arms will give way suddenly in the middle of a complicated exercise. Experience does a good deal towards removing this feeling, and those who have been “up” in previous years are sometimes so sure of themselves as to perform voluntaries on the apparatus. The present system of announcing beforehand what exercises will be set at the competition removes one flaw, namely the danger of any one school getting wind of the proposed exercises and so obtaining an unfair advantage over the rest of the schools, as actually occurred in 1900, but substitutes another by rendering the already difficult work of judging harder still.

The Queen’s Road Gymnasium is large and lofty, an ideal place for such a competition. One end of the building is reserved for the boxing, and it is here that the bulk of the audience collects. Give the average Briton the choice between a warm turn-up with the gloves and the best of gymnastic displays, and he will generally choose the former.

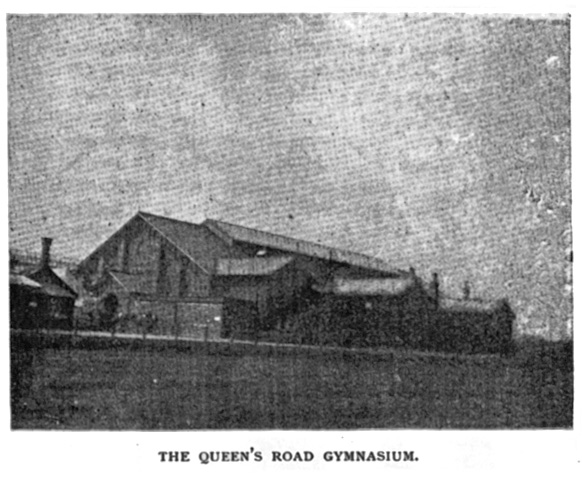

Midway between the two walls is a stage draped with tricolour, raised breast-high. On this is the ring, a roped-in space 18 ft square; at the corners are padded posts, about 3 ft. in height, joined by wrapped ropes, white at the top, red at the bottom. On all four sides are raised tiers of seats, filled with a very mixed assemblage—soldiers of all ranks, civilians of all sorts and of both sexes, for the boxing, in spite of the vital fluid that flows steadily throughout, possesses a magnetic attraction for the fair sex.

Twelve o’clock. The boxers draw numbered slips of paper from a bowl. This done, the two who have drawn the slips bearing the figure 1 enter from the dressing-room and mount the stage. A nervous moment this, even for the most hardened pugilist. In boxing at school one has at any rate a general idea of the style and calibre of one’s opponent, but at Aldershot there is a horrible uncertainty. For all you know the man before you may be a Terry McGovern.

The pair seat themselves in their respective corners, each having two seconds allotted to him. These gentlemen certainly do their duty by him both physically and morally, now submitting his legs and arms to a vigorous massage, now indicating verbally the straight and narrow way to pugilistic salvation, in both cases with as much earnestness as if they had their last penny on him in the fight. His trainer and teacher, the school instructor, also adds his word of advice.

Then the M.C. mounts the stage and speaks his piece. “First bout. Light-weights. C. K. Jorpoint, St. Paul’s School. B. F. Jabmark, Eton College.” And then, as who should say “This point, if no other, I am determined to make thoroughly clear,” he repeats, “Jorpoint, St. Paul’s. Jabmark, Eton.”

A few more moments of suspense and the time-keeper calls, “Seconds away. Are you ready? Time.” Messrs. Jorpoint and Jabmark rise with a feeling of relief and a hazy idea that they must “keep that left going” at all costs if they mean to be Public Schools Light-Weight Champions.

“Two rounds of two minutes and one of three, Queensberry Rules, 6 oz. gloves” is the technical description of what is probably the warmest period either of the competitors is likely to experience in the course of his existence. Two rounds of two hours each it feels like. As for the so-called 6 oz. gloves, at the end of the last round they seem to turn the scale at as many pounds.

Decisions are given on points. There are two judges and a referee, the latter having the casting vote in cases of disagreement.

The fierceness of these encounters has led to a move on the part of the head-masters which can only be called Gilbertian. They have disallowed what is known in sporting circles as the funny punch, in other words the blow that puts the other man out. Thus, if A is rash enough to prod B under the jaw with the usual result, and if at the time B happens to lead on points, then it is B who, on being brought round again, is hailed as the winner, probably much to his surprise. It may be mentioned, however, that this rule holds good rather in theory than in practice, for in 1900 three such accidents happened, and in each case the verdict went to the knocker-out, not to his opponent.

The various weights display a variety of styles. A friend

of the present writer once remarked to him that the heavies were too heavy

and the feathers too feathery, which is an instance of an epigram straying

into truth. The remark applies especially to the heavies. In this department

there is little or no science. Directly a man has passed the 11 st. 4 lb.

limit he seems to consider that parrying and ducking are mere frivolities,

and that if he can get in a good blow it does not matter what his opponent

does. A heavy-weight fight, therefore, always smacks too much of the shambles

to be altogether to the taste of the squeamish spectator, though to the

Tommies in the audience it is meat and drink. The feathers generally err

on the other side—plenty of science, but not enough steam behind

their blows.

The various weights display a variety of styles. A friend

of the present writer once remarked to him that the heavies were too heavy

and the feathers too feathery, which is an instance of an epigram straying

into truth. The remark applies especially to the heavies. In this department

there is little or no science. Directly a man has passed the 11 st. 4 lb.

limit he seems to consider that parrying and ducking are mere frivolities,

and that if he can get in a good blow it does not matter what his opponent

does. A heavy-weight fight, therefore, always smacks too much of the shambles

to be altogether to the taste of the squeamish spectator, though to the

Tommies in the audience it is meat and drink. The feathers generally err

on the other side—plenty of science, but not enough steam behind

their blows.

The middle-weight boxers devote themselves mainly to in-fighting, far the best display being given by the light-weights, who combine science with a laudable determination to make their mark.

The boxing is over by three o’clock, and the spectators pour down to watch the last stage of the gymnastics. The gymnasts have been plodding steadily through their appointed task since twelve, in two batches, snatching a hasty lunch in the tents behind the Gymnasium when an opportunity occurred. The Aldershot menu, it might be remarked in passing, is not the sort that a trainer would recommend to his man; but, possibly, coming so soon before the actual performance, it has no time to work any havoc.

At the conclusion of the gymnastics the fencing is begun.

A long gangway, with a well-defined centre line, is run into the middle

of the room, and the competitors stand one at either end. They salute,

don the masks, and at the word “Attack” fall to. Some extraordinarily

wild fencing is to be seen at times. In fact, most of the competitors err

in this direction, though some very finished swordsmanship is also in evidence

occasionally. After the first bout of the foils is over, the sabres come

forward, and here the wildness is more marked than ever. These are followed

by more foils, then more sabres, and so on until both events are finished,

when everybody adjourns to the dressing-room and resumes every day garments.

While the marks for the gymnastics are being added up, the ten men who

form the Aldershot Gymnastic Staff give an exhibition which it would be

well-nigh impossible to equal. Though veterans to a man, all close on forty

years of age, they are probably the finest team of gymnasts in the world.

At the conclusion of the gymnastics the fencing is begun.

A long gangway, with a well-defined centre line, is run into the middle

of the room, and the competitors stand one at either end. They salute,

don the masks, and at the word “Attack” fall to. Some extraordinarily

wild fencing is to be seen at times. In fact, most of the competitors err

in this direction, though some very finished swordsmanship is also in evidence

occasionally. After the first bout of the foils is over, the sabres come

forward, and here the wildness is more marked than ever. These are followed

by more foils, then more sabres, and so on until both events are finished,

when everybody adjourns to the dressing-room and resumes every day garments.

While the marks for the gymnastics are being added up, the ten men who

form the Aldershot Gymnastic Staff give an exhibition which it would be

well-nigh impossible to equal. Though veterans to a man, all close on forty

years of age, they are probably the finest team of gymnasts in the world.

The marks being settled, the M.C. reads out first the names of the Shield winners, that is, the pair whose marks form the highest total of the schools, and then the two highest individual scores, rewarded by a silver and a bronze medal. These are followed by the boxing prizes, a silver and a bronze medal in each weight, and the medals for fencing and sabres. The prizes are usually awarded by Royalty.

All this time the band has been playing lustily. With the conclusion of the guest of the day’s speech, the National Anthem blares forth with loyal fervour, and with the last note the Public Schools’ Boxing, Fencing, and Gymnastic Competition for the year 19— is at an end.

Editor’s notes:

This article makes an interesting pairing with the opening chapter of The Pothunters, Wodehouse’s first novel, serialized in the Public School Magazine beginning in January 1902. One of the principal characters in the novel, Tony Graham of St. Austin’s, wins the middle-weight championship at Aldershot in that opening chapter.

feather-weights: not over 9 stone (126 lb.), defined in 1889 and still the weight limit for professional boxers, although the weight classes have been subdivided more finely in the twentieth century, and for amateur competition have been rounded to kilograms and occasionally adjusted.

light-weights: anything up to 10 stone (140 lb.) here; since 1886 the lightweight maximum for professionals has been 9 stone 9 (135 lb.)

middle-weights: 11 stone 4 lb. and under (158 lb.) here; since 1884 the middleweight maximum for professionals has been 11 stone 6 (160 lb.)

“buffed”: The Oxford English Dictionary has citations for this adjective as U.S. slang for “muscular, showing off the body” beginning in the 1980s. I’ve sent them this much earlier usage.

vital fluid that flows steadily: blood

Terry McGovern: American bantamweight and featherweight boxer (1880–1918), born John Terrence McGovern in Johnstown, Pennsylvania of Irish parents. Of his 80 professional matches, he won 65 bouts; 44 of those wins were by knockout. In January 1900 he captured the World Featherweight Championship by defeating George Dixon, holding that title through several fights at the time this article was written. He lost the title to Young Corbett II on November 28, 1901.

science: relying on skill and tactics as opposed to mere brute strength; Wodehouse always speaks with approval of science in boxing in his fiction as well as his sports reporting. See The Pothunters at the link above, and the Kid Brady stories, among many others.

shambles: here used in its older sense of “slaughterhouse”

Tommies: an abbreviation of the generic name of Tommy Atkins for British soldiers

—Notes by Neil Midkiff

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums