The Saturday Evening Post – October 7, 1916

VII

RISING waters and a fine flying scud that whipped stingingly over the side had driven most of the passengers on the Atlantic to the shelter of their staterooms or to the warm stuffiness of the library. It was the fifth evening of the voyage. For five days and four nights the ship had been racing through a placid ocean on her way to Sandy Hook; but in the early hours of this afternoon the wind had shifted to the north, bringing heavy seas. Darkness had begun to fall now. The sky was a sullen black. The white crests of the rollers gleamed faintly in the dusk, and the wind sang in the ropes.

Jimmy and Ann had had the boat deck to themselves for half an hour. Jimmy was a good sailor. It exhilarated him to fight the wind and to walk a deck that heaved and dipped and shuddered beneath his feet; but he had not expected to have Ann’s company on such an evening. She had come out of the saloon entrance, her small face framed in a hood and her slim body shapeless beneath a great cloak, and joined him in his walk.

Jimmy was in a mood of exaltation. He had passed the last few days in a condition of intermittent melancholy, consequent on the discovery that he was not the only man on board the Atlantic who desired the society of Ann as an alleviation of the tedium of an ocean voyage. The world, when he embarked on this venture, had consisted so exclusively of Ann and himself that, until the ship was well on its way to Queenstown, he had not conceived the possibility of intrusive males forcing their unwelcome attentions on her. And it had added bitterness to the bitter awakening that their attentions did not appear to be at all unwelcome. Almost immediately after breakfast on the very first day a creature, with a small black mustache and shining teeth, had descended upon Ann and, vocal with surprise and pleasure at meeting her again—he claimed, damn him, to have met her before at Palm Beach, Bar Harbor, and a dozen other places—had carried her off to play an idiotic game known as shuffleboard.

Nor was this an isolated case. It began to be borne in upon Jimmy that Ann, whom he had looked upon purely in the light of an Eve playing opposite his Adam in an exclusive Garden of Eden, was an extremely well-known and popular character. The clerk at the shipping office had lied absurdly when he had said that very few people were crossing on the Atlantic this voyage. The vessel was crammed till its sides bulged. It was loaded down, in utter defiance of the Plimsoll Law, with Rollos and Clarences and Dwights and Twombleys who had known and golfed and ridden and driven and motored and swum and danced with Ann for years. A ghastly being, entitled Edgar Something or Teddy Something, had beaten Jimmy in the race for the deck steward, the prize of which was the placing of his deck chair next to Ann’s. Jimmy had been driven from the promenade deck by the spectacle of this beastly creature lying swathed in rugs reading best sellers to her.

He had scarcely seen her to speak to since the beginning of the voyage. When she was not walking with Rollo or playing shuffleboard with Twombley, she was down below ministering to the comfort of a chronically seasick aunt, referred to in conversation as “Poor Aunt Nesta.” Sometimes Jimmy saw the little man—presumably her uncle—in the smoking room, and once he came upon the stout boy recovering from the effects of a cigar in a quiet corner of the boat deck. But apart from these meetings the family was as distant from him as if he had never seen Ann at all, let alone saved her life.

And now she had dropped down on him from heaven. They were alone together with a good clean wind and the bracing scud. Rollo, Clarence, Dwight and Twombley, not to mention Edgar or possibly Teddy, were down below—he hoped, dying. They had the world to themselves.

“I love rough weather,” said Ann, lifting her face to the wind. Her eyes were very bright. She was beyond any doubt or question the only girl on earth. “Poor Aunt Nesta doesn’t. She was bad enough when it was quite calm, but this storm has finished her. I’ve just been down below, trying to cheer her up.”

Jimmy thrilled at the picture. Always fascinating, Ann seemed to him at her best in the rôle of ministering angel. He longed to tell her so, but found no words. They reached the end of the deck and turned. Ann looked up at him.

“I’ve hardly seen anything of you since we sailed,” she said. She spoke almost reproachfully. “Tell me all about yourself, Mr. Bayliss. Why are you going to America?”

Jimmy had had an impassioned indictment of the Rollos on his tongue, but she had closed the opening for it as quickly as she had made it. In face of her direct demand for information he could not hark back to it now. After all, what did the Rollos matter? They had no part in this little wind-swept world. They were where they belonged—in some nether hell on the C or D deck, moaning for death.

“To make a fortune, I hope,” he said.

Ann was pleased at this confirmation of her diagnosis. She had deduced this from the evidence at Paddington Station.

“How pleased your father will be if you do!”

The slight complexity of Jimmy’s affairs caused him to pause for a moment to sort out his fathers, but an instant’s reflection told him that she must be referring to Bayliss, the butler.

“Yes.”

“He’s a dear old man,” said Ann. “I suppose he’s very proud of you?”

“I hope so.”

“You must do tremendously well in America, so as not to disappoint him. What are you thinking of doing?”

Jimmy considered for a moment.

“Newspaper work, I think.”

“Oh! Why, have you had any experience?”

“A little.”

Ann seemed to grow a little aloof, as if her enthusiasm had been damped.

“Oh, well, I suppose it’s a good-enough profession. I’m not very fond of it myself. I’ve only met one newspaper man in my life, and I dislike him very much, so I suppose that has prejudiced me.”

“Who was that?”

“You wouldn’t have met him. He was on an American paper. A man named Crocker.”

A sudden gust of wind drove them back a step, rendering talk impossible. It covered a gap when Jimmy could not have spoken. The shock of the information that Ann had met him before made him dumb. This thing was beyond him. It baffled him. Her next words supplied a solution. They were under shelter of one of the boats now and she could make herself heard.

“It was five years ago, and I only met him for a very short while, but the prejudice has lasted.”

Jimmy began to understand. Five years ago! It was not so strange, then, that they should not recognize each other now. He stirred up his memory. Nothing came to the surface. Not a gleam of recollection of that early meeting rewarded him. And yet something of importance must have happened then for her to remember it. Surely his mere personality could not have been so unpleasant as to have made such a lasting impression on her!

“I wish you could do something better than newspaper work,” said Ann. “I always think the splendid part about America is that it is such a land of adventure. There are such millions of chances. It’s a place where anything may happen. Haven’t you an adventurous soul, Mr. Bayliss?”

No man lightly submits to a charge, even a hinted charge, of being deficient in the capacity for adventure.

“Of course I have,” said Jimmy indignantly. “I’m game to tackle anything that comes along.”

“I’m glad of that.”

Her feeling of comradeship toward this young man deepened. She loved adventure and based her estimate of any member of the opposite sex largely on his capacity for it. She moved in a set, when at home, which was more polite than adventurous, and had frequently found the atmosphere enervating.

“Adventure,” said Jimmy, “is everything.” He paused. “Or a good deal,” he concluded weakly.

“Why qualify it like that? It sounds so tame. Adventure is the biggest thing in life.”

It seemed to Jimmy that he had received an excellent cue for a remark of a kind that had been waiting for utterance ever since he had met her. Often and often in the watches of the night, smoking endless pipes and thinking of her, he had conjured up just such a vision as this—they two walking the deserted deck alone, and she innocently giving him an opening for some low-voiced, tender speech, at which she would start, look at him quickly, and then ask him haltingly if the words had any particular application. And after that—oh, well, all sorts of things might happen. And now the moment had come. It was true that he had always pictured the scene as taking place by moonlight, and at present there was a half gale blowing out of an inky sky; also, on the present occasion anything in the nature of a low-voiced speech was absolutely out of the question owing to the uproar of the elements. Still, taking these drawbacks into consideration, the chance was far too good to miss. Such an opening might never happen again. He waited till the ship had steadied herself after an apparently suicidal dive into an enormous roller, then, staggering back to her side, spoke.

“Love is the biggest thing in life!” he roared.

“Love is the biggest thing in life!” he roared.

“What is?” shrieked Ann.

“Love!” bellowed Jimmy.

He wished a moment later that he had postponed this statement of faith, for their next steps took them into a haven of comparative calm, where some dimly seen portion of the vessel’s anatomy jutted out and formed a kind of nook where it was possible to hear the ordinary tones of the human voice. He halted there, and Ann did the same, though unwillingly. She was conscious of a modification of her mood of comradeship toward her companion. She held strong views, which she believed to be unalterable, on the subject under discussion.

“Love!” she said. It was too dark to see her face, but her voice sounded unpleasantly scornful. “I shouldn’t have thought that you would have been so conventional as that. You seemed different.”

“Eh?” said Jimmy blankly,

“I hate all this talk about love, as if it were something wonderful that was worth everything else in life put together. Every book you read and every song that you see in the shop windows is all about love. It’s as if all the people in the world were in a conspiracy to persuade themselves that there’s a wonderful something just round the corner which they can get if they try hard enough. And they hypnotize themselves into thinking of nothing else, and miss all the splendid things of life.”

“That’s Shaw, isn’t it?” said Jimmy.

“What is Shaw?”

“What you were saying. It’s out of one of Bernard Shaw’s things, isn’t it?”

“It is not.” A note of acidity had crept into Ann’s voice. “It is perfectly original.”

“I’m certain I’ve heard it before somewhere.”

“If you have that simply means that you must have associated with some sensible person.”

Jimmy was puzzled.

“But why the grouch?” he asked.

“I don’t understand you.”

“I mean, why do you feel that way about it?”

Ann was quite certain now that she did not like this young man nearly so well as she had supposed. It is trying for a strong-minded, clear-thinking girl to have her philosophy described as a grouch.

“Because I’ve had the courage to think about it for myself, and not let myself be blinded by popular superstition. The whole world has united in making itself imagine that there is something called love which is the most wonderful happening in life. The poets and novelists have simply hounded them on to believe it. It’s a gigantic swindle.”

A wave of tender compassion swept over Jimmy. He understood it all now. Naturally a girl who had associated all her life with the Rollos, Clarences, Dwights and Twombleys would come to despair of the possibility of falling in love with anyone.

“You haven’t met the right man,” he said. She had, of course, but only recently; and, anyway, he could point that out later.

“There is no such thing as the right man,” said Ann resolutely, “if you are suggesting that there is a type of man in existence who is capable of inspiring what is called romantic love. I believe in marriage ——”

“Good work!” said Jimmy, well satisfied.

“But not as the result of a sort of delirium. I believe in it as a sensible partnership between two friends who know each other well and trust each other. The right way of looking at marriage is to realize, first of all, that there are no thrills, no romances, and then to pick out someone who is nice and kind and amusing and full of life and willing to do things to make you happy.”

“Ah!” said Jimmy, straightening his tie. “Well, that’s something.”

“How do you mean—that’s something? Are you shocked at my views?”

“I don’t believe they are your views. You’ve been reading one of these stern, soured fellows who analyze things.”

Ann stamped. The sound was inaudible, but Jimmy noticed the movement.

“Cold?” he said. “Let’s walk on.”

Ann’s sense of humor reasserted itself. It was not often that it remained dormant for so long. She laughed.

“I know exactly what you are thinking,” she said. “You believe that I am posing, that those aren’t my real opinions.”

“They can’t be. But I don’t think you are posing. It’s getting on to dinner time, and you’ve got that wan, sinking feeling that makes you look upon the world and find it a hollow fraud. The bugle will be blowing in a few minutes, and half an hour after that you will be yourself again.”

“I’m myself now. I suppose you can’t realize that a pretty girl can hold such views.”

Jimmy took her arm.

“Let me help you,” he said. “There’s a knothole in the deck. Watch your step. Now listen to me: I’m glad you’ve brought up this subject—I mean the subject of your being the prettiest girl in the known world ——”

“I never said that.”

“Your modesty prevented you. But it’s a fact, nevertheless. I’m glad, I say, because I have been thinking a lot along those lines myself, and I have been anxious to discuss the point with you. You have the most glorious hair I have ever seen!”

“Do you like red hair?”

“Red-gold.”

“It is nice of you to put it like that. When I was a child all except a few of the other children called me Carrots.”

“They have undoubtedly come to a bad end by this time. If bears were sent to attend to the children who criticized Elisha your little friends were in line for a troop of tigers. But there were some of a finer fiber? There were a few who didn’t call you Carrots?”

“One or two. They called me Brick-Top.”

“They have probably been electrocuted since. Your eyes are perfectly wonderful!”

Ann withdrew her arm. An extensive acquaintance with young men told her that the topic of conversation was now due to be changed.

“I rather think you will like America,” she said.

“We are not discussing America.”

“I am. It is a wonderful country for a man who wants to succeed. If I were you I should go out West.”

“Do you live out West?”

“No.”

“Then why suggest my going there? Where do you live?”

“I live in New York.”

“I shall stay in New York then.”

Ann was wary, but amused. Proposals of marriage—and Jimmy seemed to be moving swiftly toward one—were no novelty in her life. In the course of several seasons at Bar Harbor, Tuxedo, Palm Beach, and in New York itself, she had spent much of her time foiling and discouraging the ardor of a series of sentimental youths who had laid their unwelcome hearts at her feet.

“New York is open for staying in about this time, I believe.”

Jimmy was silent. He had done his best to fight the tendency to become depressed, and had striven by means of a light tone to keep himself resolutely cheerful, but the girl’s apparently total indifference to him was too much for his spirits. One of the young men who had had to pick up the heart he had flung at Ann’s feet and carry it away for repairs had once confided to an intimate friend, after the sting had to some extent passed, that the feelings of a man who made love to Ann might be likened to the emotions which hot chocolate might be supposed to entertain on contact with vanilla ice cream. Jimmy, had the comparison been presented to him, would have indorsed its perfect accuracy. The wind from the sea, until now keen and bracing, had become merely infernally cold. The song of the wind in the rigging, erstwhile melodious, had turned into a depressing howling.

“I used to be as sentimental as anyone a few years ago,” said Ann, returning to the dropped subject. “Just after I left college I was quite maudlin. I dreamed of moons and Junes and loves and doves all the time. Then something happened which made me see what a little fool I was. It wasn’t pleasant at the time, but it had a very bracing effect.

“I have been quite different ever since. It was a man, of course, who did it. His method was quite simple. He just made fun of me, and Nature did the rest.”

Jimmy scowled in the darkness. Murderous thoughts toward the unknown brute flooded his mind.

“I wish I could meet him!” he growled.

“You aren’t likely to,” said Ann. “He lives in England. His name is Crocker—Jimmy Crocker. I spoke about him just now.”

Through the howling of the wind cut the sharp notes of a bugle. Ann turned to the saloon entrance.

“Dinner!” she said brightly. “How hungry one gets on board ship!” She stopped. “Aren’t you coming down, Mr. Bayliss?”

“Not just yet,” said Jimmy thickly.

VIII

THE noonday sun beat down on Park Row. Hurrying mortals, released from a thousand offices, congested the sidewalks, their thoughts busy with the vision of lunch. Up and down the cañon of Nassau Street the crowds moved more slowly. Candy-selling aliens jostled newsboys, and huge dray horses endeavored to the best of their ability not to grind the citizenry beneath their hoofs. Eastward, pressing on to the City Hall, surged the usual dense army of happy lovers on their way to buy marriage licenses. Men popped in and out of the subway entrances like rabbits. It was a stirring, bustling scene, typical of this nerve center of New York’s vast body.

Jimmy Crocker, standing in the doorway, watched the throngs enviously. There were men in that crowd who chewed gum; there were men who wore white-satin ties with imitation-diamond stickpins; there were men who, having smoked seven-tenths of a cigar, were eating the remainder; but there was not one with whom he would not at that moment willingly have exchanged identities. For these men had jobs. And in his present frame of mind it seemed to him that no further ingredient was needed for the recipe of the ultimate human bliss.

The poet has said some very searching and unpleasant things about the man “whose heart hath ne’er within him burn’d as home his footsteps he hath turned from wandering on a foreign strand,” but he might have excused Jimmy for feeling just then not so much a warmth of heart as a cold and clammy sensation of dismay. He would have had to admit that the words “High though his titles, proud his name, boundless his wealth as wish can claim” did not apply to Jimmy Crocker. The latter may have been “concentered all in self,” but his wealth consisted of one hundred and thirty-three dollars and forty cents; and his name was so far from being proud that the mere sight of it in the files of the New York Sunday Chronicle, the record room of which he had just been visiting, had made him consider the fact that he had changed it to Bayliss the most sensible act of his career.

The reason for Jimmy’s lack of enthusiasm as he surveyed the portion of his native land visible from his doorway is not far to seek. The Atlantic had docked on Saturday night, and Jimmy, having driven to an excellent hotel and engaged an expensive room therein, had left instructions at the desk that breakfast should be served to him at ten o’clock and with it the Sunday issue of the Chronicle. Five years had passed since he had seen the dear old rag for which he had reported so many fires, murders, street accidents and weddings; and he looked forward to its perusal as a formal taking seisin of his long-neglected country. Nothing could be more fitting and symbolic than that the first morning of his return to America should find him propped up in bed reading the good old Chronicle. Among his final meditations as he dropped off to sleep was a gentle speculation as to who was city editor now, and whether the comic supplement was still featuring the sprightly adventures of the Doughnut Family.

A wave of not unmanly sentiment passed over him on the following morning as he reached out for the paper. The skyline of New York, seen as the boat comes up the bay, has its points; and the rattle of the elevated trains and the quaint odor of the subway extend a kindly welcome; but the thing that really convinces the returned traveler that he is back on Manhattan Island is the first Sunday paper. Jimmy, like everyone else, began by opening the comic supplement; and as he scanned it a chilly discomfort, almost a premonition of evil, came upon him. The Doughnut Family was no more. He knew that it was unreasonable of him to feel as if he had just been informed of the death of a dear friend, for Pa Doughnut and his associates had been having their adventures five years before he had left the country, and even the toughest comic-supplement hero rarely endures for a decade. But, nevertheless, the shadow did fall upon his morning optimism, and he derived no pleasure whatever from the artificial rollickings of a degraded creature called Old Pop Dill-Pickle, who was offered as a substitute.

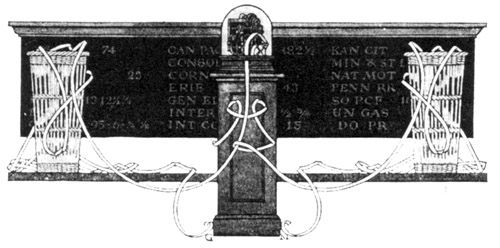

But this, he was to discover almost immediately, was a trifling disaster. It distressed him, but it did not affect his material welfare. Tragedy really began when he turned to the magazine section. Scarcely had he started to glance at it when this headline struck him like a bullet:

Piccadilly Jim at it Again

And beneath it his own name.

Nothing is so capable of diversity as the emotion we feel on seeing our name unexpectedly in print. We may soar to the heights or we may sink to the depths. Jimmy did the latter. A mere cursory first inspection of the article revealed the fact that it was no eulogy. With an unsparing hand the writer had muckraked his eventful past, the text on which he hung his remarks being that ill-fated encounter with Lord Percy Whipple at the Six Hundred Club. This the scribe had recounted at a length and with a boisterous vim which outdid even Bill Blake’s effort in the London Daily Sun. Bill Blake had been handicapped by consideration of space and the fact that he had turned in his copy at an advanced hour when the paper was almost made up. The present writer was shackled by no restrictions. He had plenty of room to spread himself in, and he had spread himself. So liberal had been the editor’s views in that respect that, in addition to the letterpress, the pages contained an unspeakably offensive picture of a burly young man, in an obviously advanced condition of alcoholism, raising his fist to strike a monocled youth in evening dress who had so little chin that Jimmy was surprised that he had ever been able to hit it. The only gleam of consolation that he could discover in this repellent drawing was the fact that the artist had treated Lord Percy even more scurvily than himself. Among other things, the second son of the Duke of Devizes was depicted as wearing a coronet—a thing which would have excited remark even in a London night club.

Jimmy read the thing through in its entirety three times before he appreciated a nuance which his disordered mind had at first failed to grasp—to wit, that this character sketch of himself was no mere isolated outburst, but apparently one of a series. In several places the writer alluded unmistakably to other theses on the same subject. Jimmy’s breakfast congealed on its tray, untouched. That boon which the gods so seldom bestow—of seeing ourselves as others see us—had been accorded to him in full measure. By the time he had completed his third reading he was regarding himself in a purely objective fashion, not unlike the attitude of a naturalist toward some strange and loathsome manifestation of insect life. So this was the sort of fellow he was! He wondered they had let him in at a reputable hotel.

The rest of the day he passed in a state of such humility that he could have wept when the waiters were civil to him. On Monday morning he made his way to Park Row to read the files of the Chronicle—a morbid enterprise, akin to the eccentric behavior of those priests of Baal who gashed themselves with knives, or of authors who subscribe to press-clipping agencies.

He came upon another of the articles almost at once, in an issue not a month old. Then there was a gap of several weeks, and hope revived that things might not be so bad as he had feared—only to be crushed by another trenchant screed. After that he set about his excavations methodically, resolved to know the worst. He knew it in just under two hours. There it all was—his row with the bookie, his bad behavior at the political meeting, his breach-of-promise case. It was a complete biography.

And the name they called him. Piccadilly Jim! Ugh!

He went out into Park Row and sought a quiet doorway where he could brood upon these matters. It was not immediately that the practical or financial aspect of the affair came to scourge him. For an appreciable time he suffered in his self-esteem alone. It seemed to him that all these bustling persons who passed knew him; that they were casting sidelong glances at him and laughing derisively; that those who chewed gum chewed it sneeringly; and that those who ate their cigars ate them with thinly veiled disapproval and scorn. Then, the passage of time blunting sensitiveness, he found that there were other and weightier things to consider.

As far as he had had any connected plan of action in his sudden casting-off of the fleshpots of London, he had determined as soon as possible after landing to report at the office of his old paper and apply for his ancient position. So little thought had he given to the minutiæ of his future plans, that it had not occurred to him that he had anything to do but walk in, slap the gang on the back and announce that he was ready to work. Work! On the staff of a paper whose chief diversion appeared to be the satirizing of his escapades! Even had he possessed the moral courage—or gall—to make the application, what good would it be? He was a byword in a world where he had once been a worthy citizen. What paper would trust Piccadilly Jim with an assignment? What paper would consider Piccadilly Jim even on space rates? A chill dismay crept over him. He seemed to hear the grave voice of Bayliss, the butler, speaking in his ear as he had spoken so short a while before at Paddington Station:

“Is it not a little rash, Mr. James?”

Rash was the word. Here he stood, in a country that had no possible use for him, a country where competition was keen and jobs for the unskilled infrequent. What on earth was there that he could do?

Well, he could go home. No, he couldn’t. His pride revolted at that solution. Prodigal Son stuff was all very well in its way, but it lost its impressiveness if you turned up again at home two weeks after you had left. A decent interval among the husks and swine was essential. Besides, there was his father to consider. He might be a poor specimen of a fellow, as witness the Sunday Chronicle passim, but he was not so poor as to come slinking back to upset things for his father just when he had done the only decent thing by removing himself. No, that was out of the question.

What remained? The air of New York is bracing and healthful, but a man cannot live on it. Obviously he must find a job. But what job?

What could he do?

A gnawing sensation in the region of the waistcoat answered the question. The solution which it put forward was, it was true, but a temporary one, yet it appealed strongly to Jimmy. He had found it admirable at many crises. He would go to lunch, and it might be that food would bring inspiration.

He moved from his doorway and crossed to the entrance of the subway. He caught a timely express, and a few minutes later emerged into the sunlight again at Grand Central. He made his way westward along Forty-second Street to the hotel which he thought would meet his needs. He had scarcely entered it when in a chair by the door he perceived Ann Chester, and at the sight of her all his depression vanished and he was himself again.

“Why, how do you do, Mr. Bayliss? Are you lunching here?”

“Unless there is some other place that you would prefer,” said Jimmy. “I hope I haven’t kept you waiting.”

Ann laughed. She was looking very delightful in something soft and green.

“I’m not going to lunch with you. I’m waiting for Mr. Ralstone and his sister. Do you remember him? He crossed over with us. His chair was next to mine on the promenade deck.”

Jimmy was shocked. When he thought how narrowly she had escaped, poor girl, from lunching with that insufferable pill, Teddy—or was it Edgar?—he felt quite weak. Recovering himself, he spoke firmly:

“When were they to have met you?”

“At one o’clock.”

“It is now five past. You are certainly not going to wait any longer. Come with me, and we will whistle for a cab.”

“Don’t be absurd!”

“Come along. I want to talk to you about my future.”

“I shall certainly do nothing of the kind,” said Ann, rising. She went with him to the door. “Teddy would never forgive me.” She got into the cab. “It’s only because you have appealed to me to help you discuss your future,” she said as they drove off. “Nothing else would have induced me ——”

“I know,” said Jimmy. “I felt that I could rely on your womanly sympathy. Where shall we go?”

“Where do you want to go? Oh, I forget that you have never been in New York before. By the way, what are your impressions of our glorious country?”

“Most gratifying, if only I could get a job.”

“Tell him to drive to Delmonico’s. It’s just round the corner on Forty-fourth Street.”

“There are some things round the corner then?”

“That sounds cryptic. What do you mean?”

“You’ve forgotten our conversation that night on the ship. You refused to admit the existence of wonderful things just round the corner. You said some very regrettable things that night. About love, if you remember.”

“You can’t be going to talk about love at one o’clock in the afternoon! Talk about your future.”

“Love is inextricably mixed up with my future.”

“Not with your immediate future. I thought you said that you were trying to get a job. Have you given up the idea of newspaper work then?”

“Absolutely.”

“Well, I’m rather glad.”

The cab drew up at the restaurant door and the conversation was interrupted. When they were seated at their table, and Jimmy had given an order to the waiter of absolutely inexcusable extravagance, Ann returned to the topic:

“Well, now the thing is to find something for you to do.”

Jimmy looked round the restaurant with appreciative eyes. The summer exodus from New York was still several weeks distant, and the place was full of prosperous-looking lunchers, not one of whom appeared to have a care or an unpaid bill in the world. The atmosphere was redolent of substantial bank balances. Solvency shone from the closely shaven faces of the men and reflected itself in the dresses of the women. Jimmy sighed.

“I suppose so,” he said. “Though for choice I’d like to be one of the Idle Rich. To my mind the ideal profession is strolling into the office and touching the old dad for another thousand.”

Ann was severe.

“You revolt me!” she said. “I never heard anything so thoroughly disgraceful. You need work!”

“One of these days,” said Jimmy plaintively, “I shall be sitting by the roadside with my dinner pail, and you will come by in your limousine, and I shall look up at you and say: ‘You hounded me into this!’ How will you feel then?”

“Very proud of myself.”

“In that case there is no more to be said. I’d much rather hang about and try to get adopted by a millionaire, but if you insist on my working —— Waiter!”

“What do you want?” asked Ann.

“Will you get me a Classified Telephone Directory?” said Jimmy.

“What for?” asked Ann.

“To look for a profession. There is nothing like being methodical.”

The waiter returned, bearing a red book. Jimmy thanked him and opened it at the A’s.

“The boy—what will he become?” he said. He turned the pages. “How about an Auditor? What do you think of that?”

“Do you think you could audit?”

“That I could not say till I had tried. I might be very good at it. How about an Adjuster?”

“An Adjuster of what?”

“The book doesn’t say. It just remarks broadly—in a sort of spacious way—‘Adjusters.’ I take it that, having decided to become an Adjuster, you then sit down and decide what you wish to adjust. One might, for example, become an Asparagus Adjuster.”

“A what?”

“Surely you know? Asparagus Adjusters are the fellows who sell those rope-and-pulley affairs by means of which the Smart Set lower asparagus into their mouths—or rather Francis the footman does it for them, of course. The diner leans back in his chair, and the menial works the apparatus in the background. It is entirely superseding the old-fashioned method of picking the vegetable up and taking a snap at it. But I suspect that to be a successful Asparagus Adjuster requires capital. We now come to Awning Crank and Spring Rollers. I don’t think I should like that. Rolling awning cranks seems to me a sorry way of spending life’s springtime. Let’s try the B’s.”

“Let’s try this omelette. It looks delicious.” Jimmy shook his head.

“I will toy with it—but absently and in a distrait manner, as becomes a man of affairs. There’s nothing in the B’s. I might devote my ardent youth to Barroom Glassware and Bottlers’ Supplies. On the other hand, I might not. Similarly, while there is no doubt a bright future for somebody in Celluloid, Fiberloid, and Other Factitious Goods, instinct tells me that there is none for”—he pulled up on the verge of saying “James Braithwaite Crocker,” and shuddered at the nearness of the pitfall—“for”—he hesitated again—“for Algernon Bayliss,” he concluded.

Ann smiled delightedly. It was so typical that his father should have called him something like that. Time had not dimmed her regard for the old man she had seen for that brief moment at Paddington Station. He was an old dear, and she thoroughly approved of this latest manifestation of his supposed pride in his offspring.

“Is that really your name—Algernon?”

“I cannot deny it.”

“I think your father is a darling,” said Ann inconsequently.

Jimmy had buried himself in the directory.

“The D’s,” he said. “Is it possible that posterity will know me as Bayliss the Dermatologist? Or as Bayliss the Drop Forger? I don’t quite like that last one. It may be a respectable occupation, but it sounds rather criminal to me. The sentence for forging drops is probably about twenty years with hard labor.”

“I wish you would put that book away and go on with your lunch,” said Ann.

“Perhaps,” said Jimmy, “my grandchildren will cluster round my knee some day and say in their piping, childish voices: ‘Tell us how you became the Elastic Stocking King, grandpa!’ What do you think?”

“I think you ought to be ashamed of yourself. You are wasting your time, when you ought to be either talking to me or else thinking very seriously about what you mean to do.”

Jimmy was turning the pages rapidly. “I will be with you in a moment,” he said. “Try to amuse yourself somehow till I am at leisure. Ask yourself a riddle. Tell yourself an anecdote. Think of life. No, it’s no good. I don’t see myself as a Fan Importer, a Glass Beveler, a Hotel Broker, an Insect Exterminator, a Junk Dealer, a Kalsomine Manufacturer, a Laundryman, a Mausoleum Architect, a Nurse, an Oculist, a Paper Hanger, a Quilt Designer, a Roofer, a Ship Plumber, a Tinsmith, an Undertaker, a Veterinarian, a Wig Maker, an X-ray Apparatus Manufacturer, a Yeast Producer or a Zinc Spelter.” He closed the book. “There is only one thing to do. I must starve in the gutter. Tell me—you know New York better than I do—where is there a good gutter?”

At this moment there entered the restaurant an Immaculate Person. He was a young man attired in faultlessly fitting clothes, with shoes of flawless polish and a perfectly proportioned floweret in his buttonhole. He surveyed the room through a monocle. He was a pleasure to look upon, but Jimmy, catching sight of him, started violently and felt no joy at all—for he had recognized him. It was a man he knew well and who knew him well, a man whom he had last seen a bare two weeks ago at the Bachelors’ Club in London. Few things are certain in this world, but one was that, if Bartling—such was the Vision’s name—should see him, he would come over and address him as Crocker. He braced himself to the task of being Bayliss, the whole Bayliss and nothing but Bayliss. It might be that stout denial would carry him through. After all, Reggie Bartling was a man of notoriously feeble intellect, who could believe in anything.

The monocle continued its sweep. It rested on Jimmy’s profile.

“By Gad!” said the Vision.

Reginald Bartling had landed in New York that morning, and already the loneliness of a strange city had begun to oppress him. He had come over on a visit of pleasure, his suit case stuffed with letters of introduction, but these he had not yet used. There was a feeling of homesickness upon him, and he ached for a pal. And there before him sat Jimmy Crocker, one of the best. He hastened to the table.

“I say, Crocker, old chap, I didn’t know you were over here. When did you arrive?”

Jimmy was profoundly thankful that he had seen this pest in time to be prepared for him. Suddenly assailed in this fashion, he would undoubtedly have incriminated himself by recognition of his name. But, having anticipated the visitation, he was able to say a whole sentence to Ann before showing himself aware that it was he who was addressed.

“I say! Jimmy Crocker!”

Jimmy achieved one of the blankest stares of modern times. He looked at Ann. Then he looked at Bartling again.

“I think there’s some mistake,” he said. “My name is Bayliss.”

Before his stony eye the immaculate Bartling wilted. All that he had ever heard and read about doubles came to him. He was confused. He blushed. It was deuced bad form, going up to a perfect stranger like this and pretending you knew him. Probably the chappie thought he was some kind of a confidence Johnnie or something. It was absolutely rotten! He continued to blush till one could have fancied him scarlet to the ankles. He backed away, apologizing in ragged mutters. Jimmy was not insensible to the pathos of his suffering acquaintance’s position; he knew Reggie and his devotion to good form sufficiently well to enable him to appreciate the other’s horror at having spoken to a fellow to whom he had never been introduced. But necessity forbade any other course. However Reggie’s soul might writhe and however sleepless Reggie’s nights might become as a result of this encounter, he was prepared to fight it out on those lines if it took all summer. And, anyway, it was darned good for Reggie to get a jolt like that every once in a while. Kept him bright and lively.

So thinking, he turned to Ann again, while the crimson Bartling tottered off to restore his nerve centers to their normal tone at some other hostelry. He found Ann staring amazedly at him, eyes wide and lips parted.

“Odd, that!” he observed with a light carelessness which he admired extremely, and of which he would not have believed himself capable. “I suppose I must be somebody’s double. What was the name he said?”

“Jimmy Crocker!” cried Ann.

Jimmy raised his glass, sipped, and put it down.

“Oh, yes, I remember. So it was. It’s a curious thing, too, that it sounds familiar. I’ve heard the name before somewhere.”

“I was talking about Jimmy Crocker on the ship—that evening on deck.”

Jimmy looked at her doubtfully.

“Were you? Oh, yes, of course; I’ve got it now. He is the man you dislike so.”

Ann was still looking at him as if he had undergone a change into something new and strange.

“I hope you aren’t going to let the resemblance prejudice you against me?” said Jimmy. “Some are born Jimmy Crockers, others have Jimmy Crockers thrust upon them. I hope you’ll bear in mind that I belong to the latter class.”

“It’s such an extraordinary thing.”

“Oh, I don’t know. You often hear of doubles. There was a man in England a few years ago who kept getting sent to prison for things some genial stranger who happened to look like him had done.”

“I don’t mean that. Of course there are doubles. But it is curious that you should have come over here and that we should have met like this at just this time. You see, the reason I went over to England at all was to try to get Jimmy Crocker to come back here.”

“What!”

“I don’t mean that I did. I mean that I went with my uncle and aunt, who wanted to persuade him to come and live with them.”

Jimmy was now feeling completely out of his depth.

“Your uncle and aunt? Why?”

“I ought to have explained that they are his uncle and aunt too. My aunt’s sister married his father.”

“But ——”

“It’s quite simple, though it doesn’t sound so. Perhaps you haven’t read the Sunday Chronicle lately? It has been publishing articles about Jimmy Crocker’s disgusting behavior in London—they call him Piccadilly Jim, you know ——”

In print that name had shocked Jimmy. Spoken, and by Ann, it was loathly. Remorse for his painful past tore at him.

“There was another one printed yesterday.”

“I saw it,” said Jimmy, to avert description.

“Oh, did you? Well, just to show you what sort of a man Jimmy Crocker is, the Lord Percy Whipple whom he attacked in the club was his very best friend. His stepmother told my aunt so. He seems to be absolutely hopeless.” She smiled. “You’re looking quite sad, Mr. Bayliss. Cheer up! You may look like him, but you aren’t him—he?—him?—no, ‘he’ is right. The soul is what counts. If you’ve got a good, virtuous, Algernonish soul, it doesn’t matter if you’re so like Jimmy Crocker that his friends come up and talk to you in restaurants. In fact, it’s rather an advantage really. I’m sure that if you were to walk into my uncle’s office or go to my aunt and pretend to be Jimmy Crocker, who had come over after all in a fit of repentance, she would be so pleased that there would be nothing she wouldn’t do for you. You might realize your ambition of being adopted by a millionaire. Why don’t you try it? I won’t give you away.”

“Before they found me out and hauled me off to prison I should have been near you for a time. I should have lived in the same house with you, spoken to you ——!” Jimmy’s voice shook.

Ann turned her head to address an imaginary companion.

“You must listen to this, my dear,” she said in an undertone. “He speaks wonderfully! They used to call him the Boy Orator in his home town. Sometimes that, and sometimes Eloquent Algernon!”

Jimmy eyed her fixedly. He disapproved of this frivolity.

“One of these days you will try me too high ——”

“Oh, you didn’t hear what I was saying to my friend, did you?” she said in apparent concern. “But I meant it, every word. I love to hear you talk. You have such feeling!”

Jimmy attuned himself to the key of the conversation.

“Have you no sentiment in you?” he demanded. “I was just warming up too! In another minute you would have heard something worth while. You’ve damped me now. Let’s talk about my lifework again.”

“Have you thought of anything?”

“I’d like to be one of those fellows who sit in offices and sign checks, and tell the office boy to tell Mr. Rockefeller they can give him five minutes. But, of course, I should need a check book, and I haven’t got one. Oh, well, I shall find something to do all right. Now tell me something about yourself. Let’s drop the future just for a little while.”

An hour later Jimmy turned into Broadway. He walked pensively, for he had much to occupy his mind. How strange that the Petts should have come over to England to try to induce him to return to New York, and how galling that, now that he was in New York, this avenue to a prosperous future was closed by the fact that something which he had done five years ago—that he could remember nothing about it was quite maddening—had caused Ann to nurse this abiding hatred of him. He began to dream tenderly of Ann, bumping from pedestrian to pedestrian in a gentle trance.

From this trance the seventh pedestrian aroused him by uttering his name, the name which circumstances had compelled him to abandon:

“Jimmy Crocker!”

Surprise brought Jimmy back from his dreams to the hard world—surprise and a certain exasperation. It was ridiculous to be incognito in a city which he had not visited in five years, and to be instantly recognized in this way by every second man he met. He looked sourly at the man. The other was a sturdy, square-shouldered, battered young man, who wore on his homely face a grin of recognition and regard. Jimmy was not particularly good at remembering faces, but this person’s was of a kind which the poorest memory might have recalled. It was, as the advertisements say, distinctively individual. The broken nose, the exiguous forehead and the enlarged ears all clamored for recognition.

The last time Jimmy had seen Jerry Mitchell had been two years before at the National Sporting Club in London, and, placing him at once, he braced himself, as a short while ago he had braced himself to confound immaculate Reggie.

“Hello!” said the battered one.

“Hello, indeed!” said Jimmy courteously. “In what way can I brighten your life?”

The grin faded from the other’s face. He looked puzzled.

“You’re Jimmy Crocker, ain’t you?” he asked.

“No. My name chances to be Algernon Bayliss.”

Jerry Mitchell reddened.

“Scuse me. My mistake.”

He was moving off, but Jimmy stopped him. Parting from Ann had left a large gap in his life, and he craved human society.

“I know you now,” he said. “You’re Jerry Mitchell. I saw you fight Kid Burke four years ago in London.”

The grin returned to the pugilist’s face, wider than ever. He beamed with gratification.

“Gee! Think of that! I’ve quit since then. I’m working for an old guy named Pett. Funny thing, he’s Jimmy Crocker’s uncle that I mistook you for. Say, you’re a dead ringer for that guy! I could have sworn it was him when you bumped into me. Say, are you doing anything?”

“Nothing in particular.”

“Come and have a yarn. There’s a place I know just round by here.”

“Delighted.”

They made their way to the place Jerry had selected.

“What’s yours?” said Jerry Mitchell. “I’m on the wagon myself,” he added apologetically.

“So am I,” said Jimmy. “It’s the only way. No sense in always drinking and making a disgraceful exhibition of yourself in public!”

Jerry Mitchell received this homily in silence. It disposed definitely of the lurking doubt in his mind as to the possibility of this man really being Jimmy Crocker. Though outwardly convinced by the denial he had not been able to rid himself till now of a nebulous suspicion. But this convinced him. Jimmy Crocker would never have said a thing like that nor would he have refused the offer of alcohol. Jerry fell into pleasant conversation with him, his mind eased.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums