The Saturday Evening Post, April 22, 1916

NOW that it’s all over, I may as well admit that there was a time during the rather rummy affair of Rockmeteller Todd when I thought that Jeeves was going to let me down. The man had the appearance of being baffled.

Jeeves is my man, you know. Officially he pulls in his weekly wage for pressing my clothes, and all that sort of thing; but actually he’s more like what the poet Johnny called some fellow of his acquaintance who was apt to rally round him in times of need—a guide, don’t you know; philosopher, if I remember rightly, and—I rather fancy—friend.

I rely on my man Jeeves at every turn.

So, naturally, when Rocky Todd told me about his aunt, Jeeves was in on the thing from the start.

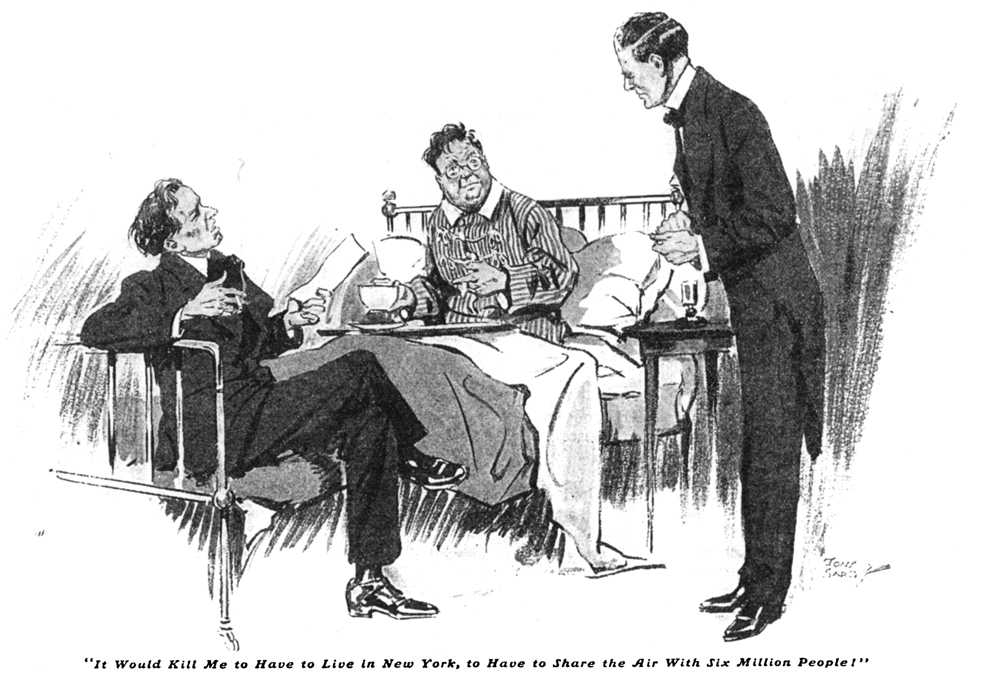

The affair of Rocky Todd broke loose early one morning in spring. I was in bed, restoring the good old tissues with about nine hours of the dreamless, when the door flew open and somebody prodded me in the lower ribs and began to shake the bedclothes. After blinking a bit and generally pulling myself together, I located Rocky—and my first impression was that it was a dream.

Rocky, you see, lived down on Long Island somewhere, miles away from New York; and not only that, but he had told me himself more than once that he never got up before twelve, and seldom earlier than one. Constitutionally the laziest young devil in America, his walk in life enabled him to go the limit in that direction. He was a poet. At least, he wrote poems when he did anything; but most of his time, as far as I could make out, he spent in a sort of trance. He told me once that he could sit on a fence, watching a worm and wondering what on earth it was up to, for hours at a stretch.

He had his scheme of life worked out to a fine point. About once a month he would take three days writing a few poems; the other three hundred and twenty-nine days of the year he rested. I didn’t know there was enough money in poetry to support a man, even in the way in which Rocky lived; but it seems that if you stick to exhortations to young men to lead the strenuous life and don’t shove in any rimes, editors fight for the stuff. Rocky showed me one of his things once. It began:

Be!

Be!

The past is dead.

To-morrow is not born.

Be to-day!

To-day!

Be with every nerve,

With every muscle,

With every drop of your red blood!

Be!

It was printed opposite the frontispiece of a magazine, with a sort of scroll round it, and a picture in the middle of a fairly nude chappie with bulging muscles, giving the rising sun the once-over. Rocky said they gave him a hundred dollars for it, and he stayed in bed till four in the afternoon for over a month.

As regarded the future, he had a moneyed aunt tucked away somewhere in Illinois; and, as he had been named Rockmetteller after her and was her only nephew, his position was pretty sound. He told me that when he did come into the money he meant to do no work at all, except perhaps an occasional poem recommending the young man with life opening out before him, with all its splendid possibilities, to light a pipe and shove his feet up on the mantelpiece.

And this was the man who was prodding me in the ribs in the gray dawn.

“Read this, Bertie!” I could just see that he was waving a letter or something equally foul in my face. “Wake up and read this!”

I can’t read before I’ve had my morning tea and a cigarette. I groped for the bell.

Jeeves came in, looking as fresh as a dewy violet. It’s a mystery to me how he does it.

“Tea, Jeeves.”

“Very good, sir.”

He flowed silently out of the room—he always gives you the impression of being some liquid substance when he moves; and I found that Rocky was surging round with his beastly letter again.

“What is it?” I said. “What on earth’s the matter?”

“Read it!”

“I can’t. I haven’t had my tea.”

“Well, listen, then.”

“Who’s it from?”

“My aunt.”

At this point I fell asleep again. I woke to hear him saying: “So what on earth am I to do?”

Jeeves trickled in with the tray, like some silent stream meandering over its mossy bed.

“Read it again, Rocky, old top,” I said. “I want Jeeves to hear it. Mr. Todd’s aunt has written him a rather rummy letter, Jeeves, and we want your advice.”

“Very good, sir.”

He stood in the middle of the room, registering devotion to the cause, and Rocky started again:

“My dear Rockmetteller: I have been thinking things over for a long while, and I have come to the conclusion that I have been very thoughtless to wait so long before doing what I have made up my mind to do now.”

“What do you make of that, Jeeves?”

“It seems a little obscure at present, sir; but no doubt the lady’s intention becomes clearer at a later point in the communication.”

“Proceed, old scout,” I said, champing my bread and butter.

“You know how all my life I have longed to visit New York and see for myself the wonderful gay life of which I have read so much. I fear that now it will be impossible for me to fulfill my dream. I am old and worn out. I seem to have no strength left in me.”

“Sad, Jeeves, what?”

“Extremely, sir.”

“Sad nothing!” said Rocky. “It’s sheer laziness. I went to see her last Christmas and she was bursting with health. Her doctor told me himself that there was nothing wrong with her whatever, and that if she would walk occasionally instead of driving, and cut her meals down to three a day, she could sign articles with Jess Willard in a couple of weeks. But she will insist that she’s a hopeless invalid; so he has to agree with her. She’s got a fixed idea that the trip to New York would kill her; so, though it’s been her ambition all her life to come here, she stays where she is.”

“Rather like the chappie whose heart was ‘in the Highlands a-chasing of the deer,’ Jeeves?”

“The cases are in some respects parallel, sir.”

“Carry on, Rocky, dear boy.”

“So I have decided that, if I cannot enjoy all the marvels of the city myself, I can at least enjoy them through you. I suddenly thought of this yesterday after reading a beautiful poem in the Sunday paper, by Luella Delia Philpotts, about a young man who had longed all his life for a certain thing and won it in the end only when he was too old to enjoy it. It was very sad; and it touched me.”

“A thing,” interpolated Rocky bitterly, “that I’ve not been able to do in ten years.”

“As you know, you will have my money when I am gone; but until now I have never been able to see my way to giving you an allowance. I have now decided to do so—on one condition. I have written to a firm of lawyers in New York, giving them instructions to pay you quite a substantial sum each month. My one condition is that you live in New York and enjoy yourself as I have always wished to do. I want you to be my representative, to spend this money for me as I should do myself. I want you to plunge into the gay, prismatic life of New York. I want you to be the life and soul of brilliant supper parties.

“Above all, I want you—indeed, I insist on this—to write me letters at least once a week giving me a full description of all you are doing and all that is going on in the city, so that I may enjoy at secondhand what my wretched health prevents my enjoying for myself. Remember that I shall expect full details, and that no detail is too trivial to interest

Your affectionate aunt,

“Isabel Rockmetteller.”

“What about it?” said Rocky.

“What about it?” I said.

“Yes. What on earth am I going to do?”

It was only then that I really got on to the extremely rummy attitude of the chappie, in view of the fact that a quite unexpected mess of the right stuff had suddenly descended on him from a blue sky.

“Aren’t you bucked?” I said.

“Bucked!”

“If I were in your place I should be frightfully braced. I consider this pretty soft for you.”

He gave a kind of yelp, goggled at me for a moment, and then began to talk of New York in a way that reminded me of Jimmy Mundy, the evangelist chappie. Jimmy had just come to New York on a hit-the-trail campaign, and I had popped in at the Garden a couple of days before, for half an hour or so, to hear him. He had certainly handed New York some pretty hot stuff about itself, having apparently taken a dislike to the place; but, by Jove, you know, dear old Rocky made him look like a publicity agent for the old metrop!

“Pretty soft!” he yowled. “To have to come and live in New York! To have to leave my little cottage and take a damned, stuffy, smelly, overheated hole of an apartment in this heaven-forsaken, festering Gehenna! To have to mix night after night with a mob of blanked paranoiacs, who think that life is a sort of St. Vitus’ dance, and imagine that they’re having a good time because they’re making enough noise for six and drinking too much for ten! I loathe New York, Bertie. I wouldn’t come near the place if I hadn’t got to see editors occasionally. There’s a blight on it!

“It’s got moral delirium tremens. It’s the city of Dreadful Dippiness. It’s the limit! It’s the extreme edge. The very thought of staying more than a day in it gives me the willies clear down my spine. And you call this thing pretty soft for me!”

I felt rather like Lot’s friends must have done when they dropped in for a quiet chat and their genial host began to criticize the Cities of the Plain. I had no idea old Rocky could be so eloquent.

“It would kill me to have to live in New York,” he went on. “To have to share the air with six million people! To have to wear stiff collars and decent clothes all the time! To ——”

He started.

“Good Lord! I suppose I should have to dress for dinner in the evenings. What a ghastly notion!”

I was shocked, absolutely shocked.

“My dear chap!” I said reproachfully.

“Do you dress for dinner every night, Bertie?”

“Jeeves,” I said coldly. The man was still standing like a statue by the door. “How many suits of evening clothes have I?”

“We have three suits of full evening dress, sir, and three dinner jackets. We have also seven white waistcoats.”

“And shirts?”

“Four dozen, sir.”

“And white ties?”

“The first two shallow shelves in the chest of drawers are completely filled with our white ties, sir.”

I turned to Rocky.

“You see?”

The chappie writhed like an electric fan.

“I won’t do it! I can’t do it! I’ll be hanged if I’ll do it! How on earth can I dress up like that? Do you realize that most days I don’t get out of my pyjamas till five in the afternoon, and then I just put on an old sweater?”

I saw Jeeves wince, poor chap. This sort of revelation shocked his finest feelings.

“Then what are you going to do about it?” I said.

“That’s what I want to know.”

“You might write and explain to your aunt.”

“I might—if I wanted her to get round to her lawyer’s in two rapid leaps and cut me out of her will.”

I saw his point.

“What do you suggest, Jeeves?” I said.

Jeeves cleared his throat respectfully.

“The crux of the matter would appear to be, sir, that Mr. Todd is obliged, by the conditions under which the money is delivered into his possession, to write Miss Rockmetteller long and detailed letters relating to his movements; and the only method by which this can be accomplished, if Mr. Todd adheres to his expressed intention of remaining in the country, is for Mr. Todd to induce some second party to gather the actual experiences which Miss Rockmetteller wishes reported to her, and to convey these to him in the shape of a careful report, on which it would be possible for him, with the aid of his imagination, to base the suggested correspondence.”

Having got which off the old diaphragm, Jeeves was silent. Rocky looked at me in a helpless sort of way. He hasn’t been brought up on Jeeves, as I have, and he isn’t onto his curves.

“Could he put it a little clearer, Bertie,” he said. “I thought at the start it was going to make sense, but it kind of flickered. What’s the idea?”

“My dear old man, perfectly simple. I knew we could stand on Jeeves. All you’ve got to do is to get somebody to go round the town for you and take a few notes, and then you work the notes up into letters. That’s it, isn’t it, Jeeves?”

“Precisely, sir.”

The light of hope gleamed in Rocky’s eyes. He looked at Jeeves in a startled way, dazed by the man’s vast intellect.

“But who would do it?” he said. “It would have to be a pretty smart sort of man, a man who would notice things.”

“Jeeves!” I said. “Let Jeeves do it! You would, wouldn’t you, Jeeves?”

For the first time in our long connection I observed Jeeves almost smile. The corner of his mouth curved quite a quarter of an inch, and for a moment his eye ceased to look like a meditative fish’s.

“I should be delighted to oblige, sir. As a matter of fact, I have already visited some of New York’s places of interest on my evenings out, and it would be most enjoyable to make a practice of the pursuit.”

“Fine! I know exactly what your aunt wants to hear about, Rocky. She wants cabaret stuff. The place you ought to go to first, Jeeves, is Reigelheimer’s. It’s on Forty-second Street. Anybody will show you the way.” Jeeves shook his head.

“Pardon me, sir. People are no longer going to Reigelheimer’s. The place at the moment is Frolics on the Roof.”

“You see?” I said to Rocky. “Leave it to Jeeves!”

It isn’t often that you find an entire group of your fellow humans happy in this world; but our little circle was certainly an example of the fact that it can be done. We were all full of beans. Everything went absolutely right from the start.

Jeeves was happy, partly because he loves to exercise his giant brain, and partly because he was having a corking time among the bright lights. I saw him one night at the Midnight Revels. He was sitting at a table on the edge of the dancing floor, doing himself remarkably well with a fat cigar and a bottle of the best. His face wore an expression of austere benevolence and he was making notes in a small book.

As for the rest of us, I was feeling pretty good, because I was fond of old Rocky and glad to be able to do him a good turn. Rocky was perfectly contented, because he was still able to sit on fences in his pyjamas and watch worms. And as for the aunt, she seemed tickled to death. She was getting Broadway at pretty long range, but it seemed to be hitting her just right. I read one of her letters to Rocky, and it was full of life.

But then Rocky’s letters, based on Jeeves’ notes, were enough to buck anybody up. It was rummy when you came to think of it. There was I, loving the life, while the mere mention of it gave Rocky a tired feeling; yet here is a letter I wrote home to a pal of mine in London:

Dear Freddie: Well, here I am in New York. It’s not a bad place. I’m not having a bad time. Everything’s pretty all right. The cabarets aren’t bad. Don’t know when I shall be back. How’s everybody?

Yours,

Bertie.

P. S. Seen old Ted lately?

Not that I cared about old Ted; but if I hadn’t dragged him in I couldn’t have got the thing onto the second page. Now here’s old Rocky on exactly the same subject:

Dearest Aunt Isabel: How can I ever thank you enough for giving me the opportunity to live in this astounding city? New York seems more wonderful every day.

Fifth Avenue is at its best, of course, just now. The dresses are magnificent!—[Wads of stuff about the dresses. I didn’t know Jeeves was such an authority.]

I was out with some of the crowd at the Midnight Revels the other night. We took in a show first, after a little dinner at a new place on Forty-third Street. We were quite a gay party. Georgie Cohan looked in about midnight and got off a good one about Willie Collier. Fred Stone could only stay a minute; but Doug. Fairbanks did all sorts of stunts and made us roar. Diamond Jim Brady was there, as usual, and Laurette Taylor showed up with a party. The show at the Revels is quite good. I am inclosing a program.

Last night a few of us went round to Frolics on the Roof——

And so on and so forth—yards of it. I suppose it’s the artistic temperament or something. What I mean is, it’s easier for a chappie who’s used to writing poems and that sort of tosh to put a bit of a punch into a letter than it is for a chappie like me. Anyway, there’s no doubt that Rocky’s correspondence was hot stuff. I called Jeeves in and congratulated him: “Jeeves, you’re a wonder!”

“Thank you, sir.”

“How you notice everything at these places beats me! I couldn’t tell you a thing about them, except that I’ve had a good time.”

“It’s just a knack, sir.”

“Well, Mr. Todd’s letters ought to brace Miss Rockmetteller all right, what?”

“Undoubtedly, sir.”

And, by Jove, they did! They certainly did, by George! What I mean to say is, I was sitting in the apartment one afternoon, about a month after the thing had started, smoking and resting the old bean, when the door opened and the voice of Jeeves burst the silence like a bomb.

It wasn’t that he spoke loud. He has one of those soft, soothing voices that slide through the atmosphere like the note of a far-off sheep. It was what he said that made me leap like a young gazelle:

“Miss Rockmetteller!”

And in came a large, solid female.

The situation had me weak. I’m not denying it. Hamlet must have felt much as I did when his father’s ghost bobbed up in the fairway. I’d come to look on Rocky’s aunt as such a permanency at her own home that it didn’t seem possible that she could really be here in New York. I stared at her. Then I looked at Jeeves. He was standing there in an attitude of dignified detachment, the chump, when if ever he should have been rallying round the young master it was now.

Rocky’s aunt looked less like an invalid than anyone I’ve ever seen, except my Aunt Agatha. She had a good deal of Aunt Agatha about her, as a matter of fact. She looked as if she might be deucedly dangerous if put upon; and something seemed to tell me that she would certainly regard herself as put upon if she ever found out the game which poor old Rocky had been pulling on her.

“Good afternoon,” I managed to say.

“How do you do?” she said. “Mr. Cohan?”

“Er—no.”

“Mr. Fred Stone?”

“Not absolutely. As a matter of fact, my name’s Wooster—Bertie Wooster.”

She seemed disappointed. The fine old name of Wooster appeared to mean nothing in her life.

“Isn’t Rockmetteller home?” she said. “Where is he?”

She had me with the first shot. I couldn’t think of anything to say. I couldn’t tell her that Rocky was down in the country, watching worms.

There was the faintest flutter of sound in the background. It was the respectful cough with which Jeeves announces that he is about to speak without having been spoken to.

“If you remember, sir, Mr. Todd went out in the automobile with a party earlier in the afternoon.”

“So he did, Jeeves; so he did,” I said, looking at my watch. “Did he say when he would be back?”

“He gave me to understand, sir, that he would be somewhat late in returning.”

He vanished; and the aunt took the chair which I’d forgotten to offer her. She looked at me in rather a rummy way. It was a nasty look. It made me feel as if I were something the dog had brought in and intended to bury later on, when he had time. My own Aunt Agatha, back in England, has looked at me in exactly the same way many a time, and it never fails to make my spine curl.

“You seem very much at home here, young man. Are you a great friend of Rockmetteller’s?”

“Oh, yes, rather!”

She frowned as if she had expected better things of old Rocky.

“Well, you need to be,” she said, “the way you treat his apartment as your own!”

I give you my word, this quite unforeseen slam simply robbed me of the power of speech. I’d been looking on myself in the light of the dashing host, and suddenly to be treated as an intruder jarred me. It wasn’t, mark you, as if she had spoken in a way to suggest that she considered my presence in the place as an ordinary social call. She obviously looked on me as a cross between a burglar and the plumber’s man come to fix the leak in the bathroom. It hurt her—my being there.

At this juncture, with the conversation showing every sign of being about to die in awful agonies, an idea came to me. Tea—the good old stand-by.

“Would you care for a cup of tea?” I said.

“Tea?”

She spoke as if she had never heard of the stuff.

“Nothing like a cup after a journey,” I said. “Bucks you up! Puts a bit of zip into you. What I mean is, restores you, and so on, don’t you know. I’ll go and tell Jeeves.”

I tottered down the passage to Jeeves’ lair. The man was reading the evening paper as if he hadn’t a care in the world.

“Jeeves,” I said, “we want some tea.”

“Very good, sir.”

“I say, Jeeves, this is a bit thick, what?”

I wanted sympathy, don’t you know—sympathy and kindness. The old nerve centers had had the deuce of a shock.

“She’s got the idea this place belongs to Mr. Todd. What on earth put that into her head?”

Jeeves filled the kettle, with a restrained dignity.

“No doubt because of Mr. Todd’s letters, sir,” he said. “It was my suggestion, sir, if you remember, that they should be addressed from this apartment in order that Mr. Todd should appear to possess a good central residence in the city.”

I remembered. We had thought it a brainy scheme at the time.

“Well, it’s bally awkward, you know, Jeeves. She looks on me as an intruder. By Jove, I suppose she thinks I’m some one who hangs about here, touching Mr. Todd for free meals and borrowing his shirts!”

“Highly probable, sir.”

“It’s pretty rotten, you know.”

“Most disturbing, sir.”

“And there’s another thing: What are we to do about Mr. Todd? We’ve got to get him up here as soon as ever we can. When you have brought the tea you had better go out and send him a telegram, telling him to come up by the next train.”

“I have already done so, sir. I took the liberty of writing the message and dispatching it by the lift attendant.”

“By Jove, you think of everything, Jeeves!”

“Thank you, sir. A little buttered toast with the tea? Just so, sir. Thank you.”

I went back to the sitting room. She hadn’t moved an inch. She was still bolt upright on the edge of her chair, gripping her umbrella like a hammer thrower. She gave me another of those looks as I came in. There was no doubt about it; for some reason she had taken a dislike to me. I suppose because I wasn’t George M. Cohan. It was a bit hard on a chap.

“This is a surprise, what?” I said, after about five minutes’ restful silence, trying to crank the conversation up again.

“What is a surprise?”

“Your coming here, don’t you know, and so on.”

She raised her eyebrows and drank me in a bit more through her glasses.

“Why is it surprising that I should visit my only nephew?”

Put like that, of course, it did seem reasonable.

“Oh, rather,” I said. “Of course! Certainly. Go the limit! What I mean is ——”

Jeeves projected himself into the room with the tea. I was jolly glad to see him. There’s nothing like having a bit of business arranged for one when one isn’t certain of one’s lines. With the teapot to fool about with, I felt happier.

“Tea, tea, tea—what? What?” I said.

It wasn’t what I had meant to say. My idea had been to be a good deal more formal, and so on. Still, it covered the situation. I poured her out a cup. She sipped it and put the cup down with a shudder.

“Do you mean to say, young man,” she said frostily, “that you expect me to drink this stuff?”

“Rather! Bucks you up, you know.”

“What do you mean by the expression ‘Bucks you up’?”

“Well, makes you full of beans, you know. Makes you fizz.”

“I don’t understand a word you say. You’re English, aren’t you?”

I admitted it. She didn’t say a word. And somehow she did it in a way that made it worse than if she had spoken for hours. Somehow it was brought home to me that she didn’t like Englishmen, and that if she had had to meet an Englishman I was the one she’d have chosen last.

Conversation languished again after that. I had another stab at boosting the session into a feast of reason and a flow of soul.

“Dear old Rocky——”

“Who?”

“Your nephew, you know.”

“Oh!”

“He—er—always gave me the idea that you were pretty much the invalid.”

“Did he?”

“Bed of sickness, and all that sort of thing, you know.”

“Indeed!”

Eight bars’ rest. I tried again. I was becoming more convinced every moment that you can’t make a real lively salon with a couple of people, especially if one of them lets it go a word at a time.

“Are you comfortable at your hotel?” I said.

“At which hotel?”

“The hotel you’re staying at.”

“I am not staying at a hotel.”

“Stopping with friends—what?”

“I am naturally stopping with my nephew.”

I didn’t get it for a moment; then it hit me.

“What! Here?” I gurgled.

“Certainly. Where else should I go?”

The full horror of the situation rolled over me like a wave. I couldn’t see what on earth I was to do. I couldn’t explain that this wasn’t Rocky’s apartment without giving the poor old chap away hopelessly, because she would then ask me where he did live and then he would be right in the soup. I was trying to induce the old bean to recover from the shock and produce some results, when she spoke again: “Will you kindly tell my nephew’s manservant to prepare my room. I wish to lie down.”

“Your nephew’s manservant?”

“The man you call Jeeves. If Rockmetteller has gone for an automobile ride there is no need for you to wait for him. He will naturally wish to be alone with me when he returns.”

I found myself tottering out of the room. The thing was too much for me. I crept into Jeeves’ den.

“Jeeves!” I whispered.

“Sir?”

“Mix me a b-and-s, Jeeves. I feel weak.”

“Very good, sir.”

“This is getting thicker every minute, Jeeves.”

“Sir?”

“I feel as if I’d been through a hold-up. Jesse James was an amateur compared with this woman. Captain Kidd wasn’t in her class. She’s pinched the apartment!”

“Sir?”

“Pinched it lock, stock and barrel, just as it stands, and kicked me out. And, as if that wasn’t enough, she’s pinched you!”

“Pinched me, sir?”

“Yes. She thinks you’re Mr. Todd’s man. She thinks the whole place is his, and everything in it. I don’t see what you’re to do, except stay on and keep it up. We can’t say anything or she’ll get onto the whole thing, and I don’t want to let Mr. Todd down. By the way, Jeeves, she wants you to prepare her bed.”

He looked wounded.

“It is hardly my place, sir ——”

“I know—I know. But do it as a personal favor to me. If you come to that, it’s hardly my place to be flung out of the apartment like this and have to go to a hotel, what?”

“Is it your intention to go to a hotel, sir? What will you do for clothes?”

“Good Lord! I hadn’t thought of that. Can you put a few things in a bag when she isn’t looking and sneak them down to me at the St. Aurea?”

“I will endeavor to do so, sir.”

“Well, I don’t think there’s anything more, is there? Tell Mr. Todd where I am when he gets here.”

“Very good, sir.”

I looked round the place. The moment of parting had come. I felt sad. The whole thing reminded me of one of those melodramas where they drive chappies out of the old homestead into the snow.

“Good-by, Jeeves,” I said.

“Good-by, sir.”

And I staggered out.

You know, I rather think I agree with those poet-and-philosopher Johnnies who insist that a fellow ought to be devilish pleased if he has a bit of trouble. All that stuff about being refined by suffering, you know. Suffering does give a chap a sort of broader and more sympathetic outlook. It helps you to understand other people’s misfortunes if you’ve been through the same thing yourself.

As I stood in my lonely bedroom at the hotel, trying to tie my white tie myself, it struck me for the first time that there must be whole squads of chappies in the world who had to get along without a man to look after them. When you come to think of it, there must be quite a lot of fellows who have to press their own clothes themselves, and haven’t got anybody to bring them tea in the morning, and so on. It was rather a solemn thought, don’t you know. I mean to say, ever since then I’ve been able to appreciate the frightful privations the poor have to stick.

I got dressed somehow. Jeeves hadn’t forgotten a thing in his packing. Everything was there, down to the final stud. I’m not sure this didn’t make me feel worse. It kind of deepened the pathos. It was like what somebody or other wrote about the touch of a vanished hand.

I had a bit of dinner somewhere and went to a show of some kind; but nothing seemed to make any difference. I simply hadn’t the heart to go on to supper anywhere. I just sucked down a highball in the hotel smoking room and went straight up to bed. I don’t know when I’ve felt so rotten. Somehow I found myself moving about the room softly, as if there had been a death in the family. If I had had anybody to talk to I should have talked in a whisper; in fact, when the telephone bell rang I answered in such a sad, hushed voice that the fellow at the other end of the wire said “Hello!” five times, thinking he hadn’t got me.

It was Rocky. The poor old scout was deeply agitated.

“Bertie! Is that you, Bertie?”

“This is me, old man.”

“Then why the devil didn’t you answer before?”

“I did.”

“I didn’t hear you.”

“I didn’t speak very loud. I’m much narked.”

“You haven’t anything on me. Oh, gosh! I’m having a time!”

“Where are you speaking from?”

“The Midnight Revels. We’ve been here an hour and I think we’re a fixture for the night. I’ve told Aunt Isabel I’ve gone out to call up a friend to join us. She’s glued to a chair, with this-is-the-life written all over her, taking it in through the pores. She loves it, and I’m nearly dippy.”

Rummy, how one perks up when one realizes that somebody else is copping it also! I began to feel almost braced.

“Tell me all, old top,” I said.

He began to push it out at such a speed that I had to ask him to put the brake on, because all I was getting was a loud buzzing noise. The poor old hound was undoubtedly piqued, and even peeved.

“A little more of this,” he said, “and I shall sneak quietly off to the river and end it all. Do you mean to say you go through this sort of thing every night, Bertie, and enjoy it? It’s simply infernal! I was snatching a wink of sleep behind the bill of fare just now when about a million yelling girls swooped down, with toy balloons. There are two orchestras here, each trying to see if it can’t play louder than the other. I’m a mental and physical wreck. When your telegram arrived I was just lying down for a quiet pipe with a sense of absolute peace stealing over me. I had to get dressed and sprint two miles to make the train. It nearly gave me heart failure; and on top of that I almost got brain fever inventing lies to tell Aunt Isabel. And then I had to cram myself into these damned evening clothes of yours.”

I gave a sharp wail of agony. It hadn’t struck me till then that Rocky was depending on my wardrobe to see him through.

“You’ll ruin them!”

“I hope so,” said Rocky in the most unpleasant way. His troubles seemed to have had the worst effect on his character. “I should like to get back at them somehow; they’ve given me a bad enough time. They’re about three sizes too small, and something’s apt to give at any moment. I wish to goodness it would and give me a chance to breathe. I haven’t breathed since half past seven. Thank heaven, Jeeves managed to get out and buy me a collar that fitted, or I should be a strangled corpse by now. It was touch and go till the stud broke. Bertie, this is pure Hades! Aunt Isabel keeps on urging me to dance. How on earth can I dance when I don’t know a soul to dance with? And how the deuce could I, even if I knew every girl in the place? It’s taking big chances even to move in these trousers. I had to tell her I’ve hurt my ankle. She keeps asking me when Cohan and Stone are going to turn up; and it’s simply a question of time before she discovers that Stone is sitting two tables away. Something’s got to be done, Bertie! You’ve got to think up some way of getting me out of this mess. It was you who got me into it.”

“Me! What do you mean?”

“Well, Jeeves, then. It’s all the same. It was you who suggested leaving it to Jeeves. It was those letters I wrote from his notes that did the mischief. I made them too good! My aunt’s just been telling me about it. She says she had resigned herself to ending her life where she was, and then my letters began to arrive, boosting the joys of New York; and they stimulated her to such an extent that she pulled herself together and made the trip. She seems to think she’s had some miraculous kind of faith cure. I tell you I can’t stand it, Bertie! It’s got to end!”

“Can’t Jeeves think of anything?”

“No. He just hangs round, saying ‘Most disturbing, sir!’ A fat lot of help that is!”

“But, Rocky, old top, it’s too bally awful! You’ve no notion of what I’m going through in this beastly hotel, without Jeeves. I must get back to the apartment.”

“Don’t come near the apartment!”

“But it’s my own apartment.”

“I can’t help that. There’s a dead line for you at the other end of the block. Aunt Isabel doesn’t like you. She isn’t clear in her remarks on the subject, but she says something about tea and a wrist watch. When she mentions you at all she refers to you as ‘that guffin.’

“She asked me what you did for a living,” Rocky went on. “And when I told her you didn’t do anything she said she thought as much, and that you were a typical specimen of a useless and decaying aristocracy. So if you think you have made a hit, forget it. Now I must be going back or she’ll be coming out here after me. Good-by.”

Next morning Jeeves came round. It was all so homelike when he floated noiselessly into the room that I nearly broke down.

“Good morning, sir,” he said. “I have brought a few more of your personal belongings.”

He began to unstrap the suit case he was carrying.

“Did you have any trouble sneaking them away?”

“It was not easy, sir. I had to watch my chance. Miss Rockmetteller is a remarkably alert lady.”

“You know, Jeeves, say what you like—this is a bit thick, isn’t it?”

“We must hope for the best, sir.”

“Can’t you think of anything to do?”

“I have been giving the matter considerable thought, sir, but so far without success. I am placing three silk shirts—the dove-colored, the light blue and the mauve—in the first long drawer, sir.”

“You don’t mean to say you can’t think of anything, Jeeves?”

“For the moment, sir, no. You will find a dozen handkerchiefs and the tan socks in the upper drawer on the left.” He strapped the suit case and put it on a chair. “A curious lady, Miss Rockmetteller, sir.”

“You understate it, Jeeves. By the way, Jeeves, you don’t happen to know what a guffin is, do you?”

“I am afraid not, sir.” He gazed meditatively out of the window. “In many ways, sir, Miss Rockmetteller reminds me of an aunt of mine who resides in the southeast portion of London. Their temperaments are much alike. My aunt has the same taste for the pleasures of the great city. It is a passion with her to ride in hansom cabs, sir. Whenever the family take their eyes off her she escapes from the house and spends the day riding about in cabs. On several occasions she has broken into the children’s savings bank to secure the means to enable her to gratify this desire.”

“I love to have these little chats with you about your female relatives, Jeeves,” I said coldly, for I felt that the man had let me down and I was fed up with him; “but I don’t see what all this has got to do with my trouble.”

“I beg your pardon, sir. I am leaving a small assortment of our neckties on the mantelpiece, sir, for you to select according to your preference. I should recommend the blue with the red domino pattern, sir.”

Then he streamed imperceptibly toward the door and flowed silently out.

I’ve often heard that chappies, after some great shock or loss, have a habit, after they’ve been on the floor for a while wondering what hit them, of picking themselves up and piecing themselves together, and sort of taking a whirl at beginning a new life. Time, the great healer, and Nature, adjusting itself, and so on and so forth. There’s a lot in it. I know, because in my own case, after a day or two of what you might call prostration, I began to recover.

New York’s a small place when it comes to the part of it that wakes up just as the rest is going to bed; and it wasn’t long before my tracks began to cross old Rocky’s. I saw him once at Peale’s, and again at Frolics on the Roof. There wasn’t anybody with him either time except the aunt, and, though he was trying to look as if he had struck the ideal life, it wasn’t difficult for me, knowing the circumstances, to see that beneath the mask the poor blighter was suffering.

The next two nights I didn’t come across them; but the night after that I was sitting by myself at the Maison Pierre when somebody tapped me on the shoulder blade, and I found Rocky standing beside me with a sort of mixed expression of wistfulness and apoplexy on his face. How the chappie had contrived to wear my evening clothes so many times without disaster was a mystery to me. He confided later that early in the proceedings he had slit the waistcoat up the back and that that had helped a bit.

For a moment I had the idea that he had managed to get away from his aunt for the evening; but, looking past him, I saw that she was in again. She was at a table over by the wall, looking at me as if I were something the management ought to be complained to about.

“Bertie, old scout,” said Rocky in a quiet, sort of crushed voice, “we’ve always been pals, haven’t we? I mean, you know I’d do you a good turn if you asked me?”

“My dear old lad!” I said. The man had moved me.

“Then for heaven’s sake come over and sit at our table for the rest of the evening!”

Well, you know, there are limits to the sacred claims of friendship.

“My dear chap,” I said, “you know I’d do anything in reason; but ——”

“You must come, Bertie! You’ve got to! Something’s got to be done to divert her mind. She’s brooding about something. She’s been like that for the last two days. I think she’s beginning to suspect. She can’t understand why we never seem to meet anyone I know at these joints. A few nights ago I happened to run into two newspaper men I used to know fairly well. That kept me going for a while. They were both a good deal more tanked than I could have wished, but I introduced them to Aunt Isabel as David Belasco and Jim Corbett, and it went well. But the effect has worn off now and she’s beginning to wonder again.”

I went along. One has to rally round a pal in distress. Aunt Isabel was sitting bolt upright, as usual. It certainly did seem as if she had lost a bit of the pep with which she had started out to hit it up along Broadway. She looked as if she had been thinking a good deal about rather unpleasant things.

“You’ve met Bertie Wooster, Aunt Isabel?” said Rocky.

“I have.”

There was something in her eye that seemed to say:

“Out of a city of six million people, why did you pick on me?”

“Take a seat, Bertie. What’ll you have?” said Rocky.

And so the merry party began. It was one of those jolly, happy, bread-crumbling parties where you cough twice before you speak, and then decide not to say it after all. After we had had an hour of this wild dissipation Aunt Isabel said she wanted to go home. In the light of what Rocky had been telling me, this struck me as sinister. I had gathered that at the beginning of her visit she had had to be dragged home with ropes.

It must have hit Rocky the same way, for he gave me a pleading look.

“You’ll come along, won’t you, Bertie, and have a drink at the apartment?”

I had a feeling that this wasn’t in the contract, but there wasn’t anything to be done. It seemed brutal to leave the poor chap alone with the woman. So I went along. I had a glimpse of Jeeves as we went into the apartment, sitting in his lair, and I wished I could have called to him to rally round. Something told me that I was about to need him.

The stuff was on the table in the sitting room. Rocky took up the decanter.

“Say when, Bertie.”

“Stop!” barked the aunt. He dropped it.

I caught Rocky’s eye as he stooped to pick up the ruins. It was the eye of one who sees it coming.

“Leave it there, Rockmetteller!” said Aunt Isabel; and Rocky left it there.

“The time has come to speak,” she said. “I cannot stand idly by and see a young man going to perdition!”

Poor old Rocky gave a sort of gurgle, a kind of sound rather like the whisky had made running out of the decanter on to my carpet.

“Eh?” he said, blinking.

The aunt proceeded.

“The fault,” she said, “was mine. I had not then seen the light. But now my eyes are open. I see the hideous mistake I have made. I shudder at the thought of the wrong I did you, Rockmetteller, by urging you into contact with this wicked city.”

I saw Rocky grope feebly for the table. His fingers touched it and a look of relief came into the poor chappie’s face. I understood his feelings. Once or twice after a pretty heavy night I’ve had to touch something solid myself—a lamp-post or something—just to make sure that the world was still there. There come moments in every fellow’s life—after farewell dinners to friends about to marry, and what not—when it is not feasible to trust solely to what one sees.

“But when I wrote you that letter, Rockmetteller, instructing you to go to the city and live its life, I had not had the privilege of hearing Mr. Mundy speak on the subject of New York.”

“Jimmy Mundy!” I cried.

You know how it is sometimes when everything seems all mixed up and you suddenly get a clew. When she mentioned Jimmy Mundy I began to understand more or less what had happened. I’d seen it happen before. I remember, back in England, the man I had before Jeeves sneaked off to a revivalist meeting on his evening out and came back, having got religion, and denounced me, in front of a crowd of chappies I was giving a bit of supper to, as a moral leper. All because I wouldn’t start off with him that night to be a missionary in the Fiji Islands.

The aunt gave me the withering up and down.

“Yes; Jimmy Mundy!” she said. “I am surprised at a man of your stamp having heard of him. There is no music, there are no drunken, dancing men, no shameless, flaunting women at his meetings; so for you they would have no attraction. But for others, less dead in sin, he has his message. He has come to save New York from itself; to force it—in his picturesque phrase—to hit the trail. It was three days ago, Rockmetteller, that I first heard him. It was an accident that took me to his meeting. How often in this life a mere accident may shape our whole future!

“You had been called away by that telephone message from Mr. Belasco; so you could not take me to the Hippodrome, as we had arranged. I asked your manservant, Jeeves, to take me there. The man has very little intelligence. He seems to have misunderstood me. I am thankful that he did. He took me to what I subsequently learned was Madison Square Garden, where Mr. Mundy is holding his meetings. He escorted me to a seat and then left me. And it was not till the meeting had begun that I discovered the mistake which had been made. My seat was in the middle of a row. I could not leave without inconveniencing a great many people; so I remained.” She gulped.

“Rockmetteller, I have never been so thankful for anything else. Mr. Mundy was wonderful! He was like some prophet of old, scourging the sins of the people. He leaped about in a frenzy of inspiration till I feared he would do himself an injury. Sometimes he expressed himself in a somewhat odd manner, but every word carried conviction. Even when he described the people of New York as an aggregation of knock-kneed prunes, something seemed to tell me what he meant and how true it was.

“He said that the tango and the fox trot were devices of the Devil to drag people down into the Bottomless Pit. He said that there was more sin in ten minutes with a negro banjo orchestra than in all the ancient revels of Nineveh and Babylon. And when he stood on one leg and pointed right at where I was sitting, and shouted ‘This means you!’ I could have sunk through the floor. I came away a changed woman. Surely you must have noticed the change in me, Rockmetteller? You must have seen that I was no longer the careless, thoughtless person who had urged you to dance in those places of wickedness?”

Rocky was holding on to the table as if it was his only friend.

“Y-yes,” he yammered; “I—I thought something was wrong.”

“Wrong? Something was right! Everything was right! Rockmetteller, it is not too late for you to be saved. You have only sipped of the evil cup. You have not drained it. It will be hard at first, but you will find that you can do it if you fight with a stout heart against the glamour and fascination of this dreadful city. Won’t you, for my sake, try, Rockmetteller? Won’t you go back to the country to-morrow and begin the struggle? Little by little, if you use your will ——”

I can’t help thinking it must have been that word “will” that roused dear old Rocky like a trumpet call. It must have brought home to him the realization that a miracle had come off and saved him from being cut out of Aunt Isabel’s. At any rate, as she said it he perked up, let go of the table, and faced her with gleaming eyes.

“Do you want me to go back to the country, Aunt Isabel?”

“Yes.”

“Not to live in the country?”

“Yes, Rockmetteller.”

“Stay in the country all the time, do you mean? Never come to New York?”

“Yes, Rockmetteller; I mean just that. It is the only way. Only there can you be safe from temptation. Will you do it, Rockmetteller? Will you—for my sake?”

“I will!” he said.

“Jeeves,” I said. It was next day, and I was back in the old apartment, lying in the old armchair, with my feet up on the good old table. I had just come from seeing dear old Rocky off to his country cottage, and an hour before he had seen his aunt off to whatever hamlet in Illinois it was that she was the curse of; so we were alone at last. “Jeeves, there’s no place like home—what?”

“Very true, sir.”

“Jeeves.”

“Sir?”

“Do you know, at one point in the business I really thought you were baffled.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“When did you get the idea of taking Miss Rockmetteller to the meeting? It was pure genius!”

“Thank you, sir. It came to me a little suddenly, one morning when I was thinking of my aunt, sir.”

“Your aunt? The hansom-cab one?”

“Yes, sir. I recollected that, whenever we observed one of her attacks coming on, we used to send for the clergyman of the parish. We always found that if he talked to her a while of higher things it diverted her mind from hansom cabs.”

I was stunned by the man’s resource.

“It’s brain,” I said; “pure brain! What do you do to get like that, Jeeves? I believe you must eat a lot of fish, or something. Do you eat a lot of fish, Jeeves?”

“No, sir.”

“Oh, well then, it’s just a gift, I take it; and if you aren’t born that way there’s no use worrying.”

“Precisely, sir,” said Jeeves. “If I might make the suggestion, sir, I should not continue to wear your present tie. The green shade gives you a slightly bilious air. I should strongly advocate the blue with the red domino pattern instead, sir.”

“All right, Jeeves,” I said humbly. “You know!”

Notes:

Compare the British magazine appearance of this story.

Annotations to this story as it appeared in book form are on this site.

rimes: Wodehouse wrote “rhymes” here; the “simplified spelling” was a choice made by the Saturday Evening Post editor. See this list of the 300 words whose spellings were simplified in U. S. Government documents by a 1906 order of President Theodore Roosevelt. Wodehouse mentioned “an almost Rooseveltian passion for the new spelling” in “Rough-Hew Them How We Will” in 1910, though he was making a joke about the Middle English spellings of Chaucer there.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums