The Strand Magazine, October 1930

CHAPTER I.

i.

ON an afternoon in May, at the hour when London pauses in its labours to refresh itself with a bite of lunch, there was taking place in the coffee-room of the Drones Club in Dover Street that pleasantest of functions, a reunion of old school friends. The host at the meal was Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, son and heir of the sixth Earl of Hoddesdon, the guest his one time inseparable comrade, John Beresford Conway.

Happening that morning to go down to the City to discuss with his bank-manager a little matter of an overdraft, Lord Biskerton had run into Berry Conway in Cornhill. It was three years since they had last met, and in his lordship’s manner, as he gazed across the table, there was something of the affectionate reproach a conscientious trainer of performing fleas might have shown towards one of his artists who had strayed from the fold.

“Amazing!” he said.

Lord Biskerton was a young man with red hair and what looked like a preliminary scenario for a moustache of the same striking hue. He dug into his fried sole emotionally.

“Absolutely amazing,” he repeated. “It beats me. I am mystified. Here we have two birds—you, on the one hand; I, on the other—who were once as close as the paper on the wall. Our chumminess was a silent sermon on Brotherly Love. And yet I’m dashed if we’ve set eyes on one another since the summer Peanut Brittle won the Jubilee Handicap. I can’t understand it.”

Berry Conway shifted a little uncomfortably in his seat. He seemed embarrassed.

“We just happened to miss each other, I suppose.”

“But how?” Lord Biskerton was resolved to probe this thing to its depths. “That’s what I want to know. How? I go everywhere. Races, restaurants, theatres, all the usual round. It seems incredible that we haven’t met before. If you ask most people, they will tell you the difficult thing is to avoid meeting me. It poisons their lives, poor devils. ‘Oh, my sainted aunt!’ they mutter. ‘You again?’ and they dash down side streets, only to bump into me coming up the other way. Then why should you have been immune?”

“Just the luck of the Conways, I expect.”

“Anyway, why haven’t you looked me up? You must have known where I was. I’m in the ’phone book.”

Berry fingered his bread.

“I don’t go about much these days,” he said. “I’m living in the suburbs now, down at Valley Fields.”

“You aren’t married, are you?” asked Lord Biskerton with sudden alarm. “Not got a little wife or any rot of that sort?”

“No. I live with an old family retainer. She used to be my nurse. And she seems to think she still is,” said Berry, his face darkening. “I heard her shouting after me as I left the house this morning something about had I got on my warm woollies.”

“My dear chap!” Lord Biskerton raised his eyebrows. “These intimate details. Keep the conversation clean. She fusses over you, does she? They will, these old nurses. Why don’t you break away from this old disease? Why not pension her off?”

“Pension her off.” Berry gave a short laugh. “What with? I suppose I had better tell you, Biscuit. The reason I’ve dropped out of things and am living in the suburbs and have stopped seeing my old friends lately is that I’ve come down in the world. I’ve no money now.”

The Biscuit stared.

“No money?”

“Well, that’s exaggerating, perhaps. To be absolutely accurate, I’m better off at the moment than I’ve been for two years, because I’ve just got a job as private secretary to Frisby, the American financier. But he only pays me a few pounds a week.”

“But what on earth has been happening?” asked the Biscuit, bewildered. “At school, you were a sort of young millionaire. You jingled as you walked. A twopenny jam-sandwich for self and friend was a mere nothing to you. Where’s all the money gone to? What came unstuck?”

Berry hesitated. His had been for some time a lonely existence, and the idea of confiding his troubles to a sympathetic ear was appealing.

“Do you really want to hear the story of my life, Biscuit?” he said, wistfully. “Sure it won’t bore you?”

“Bore me? My dear chap! I’m agog. Let’s have the whole thing. Start from the beginning. Childhood—Early surroundings—Genius probably inherited from male grandparent—Push along.”

“Well, you’ve brought it on yourself, remember.”

The Biscuit mused.

“When we first met,” he said, “you were, if I recollect, about fourteen. An offensive stripling, all feet and red ears, but worth cultivating on account of your extraordinary wealth. How did you get the stuff? Honestly, I hope?”

“That came from an aunt. It was like this. I was an only child——”

“And I bet one of you was ample.”

“My mother died when I was born. I never knew my father.”

“I sometimes wish I didn’t know mine,” said the Biscuit. “The sixth Earl has his moments, but he can on occasion be more than a bit of a blister. Why didn’t you know your father? A pretty exclusive kid, were you?”

“He was killed in a railway accident when I was three. And then this aunt adopted me. Her husband had just died, leaving her a fortune. That’s where the money came from that you used to hear jingling at school. He was in the jute business, I believe. All I remember of him is that he had whiskers. My aunt did me like a prince. Sent me to school and Cambridge, and surrounded me with every circumstance of luxury and refinement, so to speak.”

The Biscuit frowned.

“Obviously,” he said, “there must be a catch somewhere. But I’m dashed if I can spot it yet. Up to now you’ve been making my mouth water.”

“The catch,” said Berry, “was this. During all those happy, halcyon years, when you and I were throwing inked darts at one another without a care in the world, my aunt, it now appears, had been going through her capital like a drunken sailor. I don’t know if she ever endowed a scheme for getting gold out of sea-water, but, if not, that’s the only one she missed. Anybody who had anything in the way of a speculation so fishy that nobody else would look at it used to come frisking up to her, waving prospectuses, and she would fall over her feet to get at her cheque-book.”

“Women,” commented the Biscuit, “ought never to be allowed cheque-books. I’ve often said so. Mugs, every one of them.”

“She died two years ago, leaving me everything she possessed. This consisted of about three tons of shares in bogus companies. I was right up against it.”

“From riches to rags, what?”

“Yes.”

“Scaly,” said the Biscuit. “Undeniably scaly.”

“My aunt’s lawyer, a man named Attwater, happened by a miracle to be one of those fellows who pop up every now and then just to show that there is a future for the human race, after all. He had an eye like a haddock and a face like teak, and whenever he came to dinner at our place he always snubbed me like a fine old gentleman of the old school if I dared to utter a word; but, my gosh, beneath that rough exterior——! He lent me two hundred pounds to keep me going—two hundred solid quid—and if ever I have a son he is going to be christened Ebenezer Attwater Conway.”

“Better not have a son,” advised the Biscuit.

“That money just saved my life. I managed, after running all over London for three months, to get a sort of job. And at night I used to sweat away at learning typing and shorthand. Eventually I got taken on as secretary by a man in the import and export business. He retired about a month ago, and very decently shoved me off on to this fellow Frisby, who was a friend of his. That’s how Frisby comes to own my poor black body now. And that,” concluded Berry, “is why I am living in the suburbs and have not been mixing much of late with the Biskertons and the rest of the gilded aristocracy. And the really damnable part of it is that at the time when the crash came I was just going to buzz off round the world on a tramp steamer. I had to give that up, of course.”

The Biscuit appeared stupefied.

“You mean to tell me,” he said, “that you’ve been avoiding me just because you were hard-up? You were ashamed of your honest poverty? I never heard anything so dashed drivelling in my life.”

Berry flushed.

“It’s all very well to talk like that. You can’t keep up with people who are much richer than you are.”

“Who can’t?”

“Nobody can.”

“Well, I’ve been doing it all my life,” said Lord Biskerton stoutly, “and—God willing—I hope to go on doing it till I am old and grey. Do you suppose for a moment, old bag, that I’m any richer than you are? Why, I only know what money is by hearsay.”

“You don’t mean that?”

“I certainly do. If you want to see real destitution, old boy, take a look at my family. I’m broke. My guv’nor’s broke. My aunt Vera’s broke. It’s a ruddy epidemic. I owe every tradesman in London. The guv’nor hasn’t tasted meat for weeks. And as for Aunt Vera, relict of the late Colonel Archibald Mace, C.V.O., she’s reduced to writing glad articles for the evening papers. You know—things on the back page pointing out that there’s always sunshine somewhere and that we ought to be bright, like the little birds in the trees. Why, I’ve known that woman’s circumstances to become so embarrassed that she actually made an attempt to borrow money from me. Me, old boy! Lazarus in person.”

“But I’ve always thought of you as rolling in money, Biscuit. You’ve got that enormous place in Sussex——”

“That’s just what’s wrong with it. Too enormous. Eats up all the family revenues, old boy. Oh, I know how you came to be misled. The error is a common one. You see a photograph in Country Life of an Earl standing in a negligent attitude outside the north-east piazza of his seat in Loamshire, and you say to yourself, ‘Lucky devil! I’ll make that bird’s acquaintance and touch him.’ Little knowing that even as the camera clicked the poor old dead-beat was wondering where on earth the money was coming from to give the piazza the lick of paint it so badly needed. What with the Land Tax and the Income Tax and the Super Tax and all the rest of the little Taxes, there’s not much in the family sock these days, old boy. It all comes down to this,” said the Biscuit, summing up. “If England wants a happy, well-fed aristocracy, she mustn’t have wars. She can’t have it both ways.”

He sighed, and fell into a thoughtful silence.

“I wish I could find some way of making a bit of money,” he said, resuming his remarks. “I don’t seem able to do it, racing. And I don’t seem able to do it at Bridge. But there must be some method. Look at all the wealthy blighters you see running round. They’ve managed to find it. I read a book the other day where a bloke goes up to another bloke in the street—perfect stranger, with a rich sort of look about him—and whispers in his ear—the first bloke does—‘A word with you, sir!’ Addressing the second bloke, you understand. ‘A word with you, sir. I know your secret!’ Upon which the second bloke turns ashy white and supports him in luxury for the rest of his life. I thought there might be something in it.”

“About seven years, I should think.”

“Well, if I try it, I’ll let you know. And if they send me to the Bastille, you can come and see me on visiting days and hand me tracts through the bars.”

He ate cheese, and returned to an earlier point in the conversation.

“What did you mean about buzzing off round the world on a tramp steamer?” he asked. “You said, if I remember, that when the fuse blew out that was what you were planning to do. It sounded cuckoo to me. Why buzz round the world in tramp steamers?”

“Well, that’s what I wanted to do—get off somewhere and have adventures. You know that thing of Kipling’s? ‘I’d like to roll to ’Rio, roll down, roll down to ’Rio. Oh, I’d like . . .”

“ ’Sh!” said the Biscuit, scandalized. “My dear chap! You can’t recite here. Against the club rules. Strong letter from the committee.”

“I WAS talking to a fellow the other day,” said Berry, with a smouldering eye, “who had just come back from Arizona. He was telling me about the Mojave Desert. He had been prospecting out there. It made me feel like a caged eagle.”

“A what?”

“Caged eagle.”

“Why?”

“Because I felt that I should never get away from Valley Fields and see anything worth seeing.”

“You’ve seen me,” said the Biscuit.

“Think of the Grand Canyon!”

Lord Biskerton closed his eyes dutifully.

“I am,” he said. “What next? Double it?”

“What chance have I of ever seeing the Grand Canyon?”

“Why not?”

Berry writhed.

“Haven’t you been listening?” he demanded.

“Certainly I’ve been listening,” replied the Biscuit, with spirit. “I haven’t missed a word. And your statement seems to me confused and rambling. As I understand you, you wish to roll to ’Rio. And you appear to be beefing because you can’t. Why can’t you? ’Rio is open for being rolled to at this season, I presume?”

“What about Attwater and that money he lent me? I can’t pay him back unless I go on earning money, can I? And how can I earn money if I chuck my job and go tramping round the world?”

“You want to pay him back?” said the Biscuit, startled.

“Of course I do.”

“In that case, there is nothing more to be said. If you intend to go through life deliberately paying back money,” said the Biscuit, a little severely, “you must be content not to roll.”

There was a silence. Berry’s face clouded.

“I get so damned restless sometimes,” he said, “I don’t know what to do with myself. Don’t you ever get restless?”

“Never. London’s good enough for me.”

“It isn’t for me. That man who had come from Arizona was telling me how you prospect in the Mojave.”

“A thing I wouldn’t do on a bet.”

“You tramp about under a blazing sun and sleep under the stars and single-jack holes in the solid rock——”

“How perfectly foul! And not a chance of getting a drink anywhere, I take it? Well, if that’s the sort of thing you’ve missed, you’re well out of it, my lad. Yes, dashed well out of it. No matter how much you may feel like a prawn in aspic.”

“I didn’t say I felt like a prawn in aspic. I said I felt like a caged eagle.”

“It’s the same thing.”

“It isn’t at all the same thing.”

“All right,” said the Biscuit, pacifically. “Let it go. Have it your own way. But do you mean to say you can’t raise even a couple of hundred quid? Weren’t any of these shares your aunt left you any good at all?”

“Just waste paper.”

“What were they?”

“I can’t remember them all. There were about five thousand of a thing called Federal Dye, and three thousand of another called the Something Development Company . . . Oh, and a mine. I’d forgotten the mine.”

“What! You really own a mine? Then you’re on velvet.”

“But it’s a dud, like everything else my aunt bought.”

“What sort of a mine?”

“I don’t know how you would describe it, because it hasn’t anything in it. It started out with some idea of being a copper mine, I believe. It’s called The Dream Come True, but it sounds to me more like a nightmare.”

“Berry, old boy,” said the Biscuit, “I repeat, and with all the emphasis at my command, that you are on velvet. Why people want copper, I can’t say. If you carry it in your trouser-pocket, it rattles. And what can you buy with it? An evening paper or a packet of butterscotch from a slot-machine. Nevertheless, it is an established fact that people do tumble over themselves to buy copper mines. What you must do—and instantly—is to sell this thing, pay old Attwater his money, (if you really are resolved on that mad project), lend me what you may see fit of the remainder, and then you would be free to go anywhere and do what you jolly well liked.”

“But I keep telling you the Dream Come True hasn’t any copper in it.”

“Well, there are always mugs in the world, aren’t there? It will be a sorry day for old England,” said Lord Biskerton, “when one can’t find some mug to buy a mine, however dud.”

Berry picked at the tablecloth. His was an imagination that never required a great deal of firing.

“Do you really think so?”

“Of course I do.”

Berry’s eyes were glowing.

“If I could find somebody who would give me enough to pay back old Attwater’s loan, I wouldn’t stay here a day. I’d get on the first boat to America and push West. I can just picture it, Biscuit. Miles of desert, with mountain ranges that seem to change their shape as you look at them. Wagon tracks. Red porphyry cliffs. People going about in sombreros and blue overalls.”

“Probably fearful bounders, all of them,” said the Biscuit. “Keep well away, is my advice. You’re not leaving me?” he asked, as Berry rose.

“I must, I’m afraid. I’ve got to get back to work.”

“Already?”

“I’m only supposed to take an hour for lunch, and to-day isn’t a good day for breaking rules. Old Frisby’s got dyspepsia again, and is a bit edgey.”

“Well, push off, if you must,” said the Biscuit, resignedly. “And don’t forget what I said about that mine. I wish I had had an aunt who had left me something like that. There have only been two aunts in my life. One is Vera, on whom I have already touched. The other, Caroline, passed on some years ago, respected by all, owing me two-and-sixpence for a cab fare.”

ii.

AT about the moment when Berry Conway, having reluctantly torn himself away from his old school friend, entered the Underground train which was to take him back to the City and the resumption of the daily round of toil, T. Paterson Frisby, his employer, was seated in his office in Pudding Lane, E.C.4, talking to his sister Josephine on the telephone.

T. Paterson Frisby was a little man who looked as if he had been constructed of some leathern material and subsequently pickled in brine. His expression, as he took up the instrument, was one of acute exasperation. His sister always irritated him, especially on the telephone, when her natural tendency to babble became intensified; and he was also suffering severely from those pangs of indigestion to which Berry had alluded in his conversation with Lord Biskerton.

The fact that he had been expecting these pangs did nothing to mitigate them. Indeed, it added to the physical anguish a spiritual remorse which was almost as unpleasant. A whole Medical College of doctors had told Mr. Frisby to avoid roast duck, and as a rule he was strong enough to do so. But last night the craving had been too much for him. He had wallowed madly and recklessly in roast duck, tucking into the stuffing like a farm-hand. To-day had come the inevitable retribution. And on top of that Josephine was calling him on the telephone.

“ ’Lo?” said Mr. Frisby, and the word was like a cry from the pit.

He took a pepsine tablet from the bottle on the desk and tossed it into his mouth—not in the gay, dashing manner of some debonair monarch flinging largess to the multitude, but sullenly, with the air of one reluctantly compelled to lend money to an importunate cadger. His gastric juices, he knew, would give him no peace till they had had the stuff, so he gave it to them.

In a world so full of beautiful things it seems a pity that one has got to talk about Mr. Frisby’s gastric juices, but it is the duty of the historian to see life steadily and see it whole.

“ ’Lo?” said Mr. Frisby.

A clear soprano answered him.

“Paterson!”

“Ugh?”

“Is that you?”

“Ugh.”

“Listen.”

“I’m listening.”

“Well, listen, then.”

“I am listening, I tell you. Get to the point. And talk quick, darn it. Remember it’s costing forty-five bucks every three minutes.”

For Mrs. Moon was speaking from her apartment on Park Avenue, New York. And though it was the woman who would pay, waste even of other people’s money was agony to Mr. Frisby. He possessed twenty million dollars himself, and loved every cent of them.

“Paterson! Listen. I’m going to Japan next week with the Henry Bessemers.”

A low moan escaped Mr. Frisby. His face, which was rather like that of a horse, twisted in pain. Of the broad principle of his sister going to Japan he approved, Japan being farther away than New York. What rived his very soul was that she should be squandering her cash to tell him so. A picture-postcard from Tokyo, with a cross and a “This is my room” against one of the windows of an hotel, would so easily have met the case.

“Is that,” he asked in a strained voice, “all you called up to say?”

“No. Listen.”

“I AM listening.”

“It’s about Ann.”

“Oh, Ann?” said Mr. Frisby, grunting to suggest that he found this a little better. His interest in his sister’s affairs was tepid, but her daughter he rather liked. He had not seen her for some years, for the shifting of the centre of his business operations had taken him away from his native land, but he remembered her as a pretty girl with a pleasingly vivacious manner.

“Really, Paterson, I am at my wits’ end about Ann.”

Mr. Frisby grunted again, this time to indicate the opinion that she had not had to travel far.

“Do you know what she did last week?”

Mr. Frisby gave a lifelike imitation of a man who has just discovered that he is sitting on an ants’ nest.

“How the devil should I know what she did last week? Do you think I’m a clairvoyant?”

“She refused Clarence Dumphry, the son of Mortimer J. Dumphry. She said he was a stiff. And Clarence is the nicest young fellow. He doesn’t drink or smoke, and he will have millions some day. And do you know what she said to the Burwash boy?”

“Who is the Burwash boy?”

“Twombley Burwash. You know. The Dwight N. Burwashes. She told him she would marry him if he would hit a policeman.”

“Do what?”

“Hit a policeman.”

“What policeman?”

“Any policeman. She said he could choose his policeman. Naturally Twombley refused. He would not do anything like that. And it’s that sort of thing all the time. I am in despair about getting her married and settled down, and I’m always in a state of the greatest alarm lest she may run off with someone impossible. She is so appallingly romantic. The ordinary young man isn’t good enough for her, it seems. Oh, dear, no! I asked her the other day what she did want, and she said something like a mixture of Gene Tunney and T. E. Lawrence and Lindbergh would do, if he looked like Ronald Colman. So, as I am going to Japan, it seems an excellent opportunity to send her over to England for the summer. Perhaps if she has a London Season she may meet someone nice.”

Mr. Frisby choked.

“Listen!” he said, tensely. “If you think you’re going to plant her on me——”

“Of course not. A bachelor establishment like yours would be most unsuitable. She must have every chance of meeting the right people. I want you to put an advertisement in the papers, asking for a lady of title to chaperon her. Somebody she can live with and go around with.”

“Ah!” said Mr. Frisby, relieved.

“And be careful what sort of a title you choose. Mrs. Henry Bessemer was telling me about a friend of hers who advertised and got a Lady Something, and she turned out to be merely the widow of a man who had been knighted for being mayor of some town in Lancashire where the King opened a city hall or something. Remember that the best kind always have a Christian name—Lady Agatha This or Lady Agatha That. That means that they’re related to a Duke or an Earl.”

“All right.”

“It’s very confusing, of course, but there seems nothing to be done about it. How is your lumbago?”

“I don’t get it.”

“Don’t be so silly. You know you’re a martyr to it.”

“I mean I can’t hear what you’re talking about. Spell it.”

“How is your L for lizard, U for union, M for mayonnaise, B for——”

“My God!” cried Mr. Frisby, deeply moved. “Are you spending solid money to ask after that? It’s better.”

“What?”

“Better—better—BETTER! B for blasted, E for extravagance, T for telephone, T for toll, E for extravagance again, and R for ruin. For Heaven’s sake, woman, hang up that receiver before you have to go over the hill to the poorhouse.”

FOR some minutes after the tumult and the shouting had died, Mr. Frisby sat brooding and inactive. Then he reached out a hand to where a pair of detachable cuffs stood stacked beside the ink-pot. A sloppy dresser who aimed at comfort rather than elegance, he was in the habit of removing these before settling down to the day’s work. And, as always happened with him in times of mental stress, their glistening surface invited literary composition. What his tablets are to the poet, his cuffs were to T. Paterson Frisby.

He picked up one of the horrible objects, and in a scrawling hand wrote the following pensée:—

Josephine is a pest.

The contemplation of this seemed to soothe him somewhat. And he was not altogether satisfied. He licked his pencil, and between the words “a” and “pest” inserted the addendum:—

gosh-darned.

It made the thing ever so much better. Stronger. More striking. A writer’s prose may come from the heart, but it is seldom that he does not need to polish, to touch up, to heighten the colour.

Content at last that he had given of his best, he hitched his chair forward a couple of inches and returned to his work.

He had been working for what seemed to him about a quarter of an hour, when he was informed that New York wanted him on the telephone again. And presently, across three thousand miles of land and water, there floated to his ears the musical voice of a young girl.

“Hello! Uncle Paterson?”

“Ugh.”

“Hello, there, Uncle Paterson. This is Ann.”

“I know it.”

“Isn’t it funny how distinctly you can hear?” said the voice, chattily. “It’s just as if——”

“——You were sitting in the next room,” said Mr. Frisby, sighing. “I know. Get on. What is it?”

“What is what?”

Mr. Frisby groaned quietly.

“What is it you want to say?” he asked, casting his eyes up in the direction of a Heaven which, he seemed to be feeling, ought never to have dreamed of allowing a good man to be persecuted like this.

Ann laughed happily.

“Oh, nothing special,” she said. “I just came for the ride, so to speak. I’m simply talking. This is a treat for me. I’ve never called anyone up on the transatlantic ’phone before. Isn’t it fascinating to think that this is costing mother about ten dollars a syllable? What a bill there’s going to be! Did she tell you she was sending me over to London?”

“Ugh.”

“I’m sailing on the Mauretania on Friday.”

“Ugh.”

“What’s it like in London?”

“Punk.”

“Why?”

“Why not?”

“Well, it’s going to look to me like my blue heaven,” said Ann, decidedly. “I never seem to meet anyone over here whose father isn’t a multi-millionaire, and, I don’t know why it is, rich men’s sons are always the worst lemons in creation. Stiffs, every one of them. I want to meet someone different. I want romance. There must be romance somewhere in the world. Don’t you think so, Uncle Paterson?”

“No!”

“Well, I do. What I’m looking for is one of those men you read about in books who meet a girl for the first time and gaze into her eyes and cry ‘My mate!’ and fold her in their arms. And I sha’n’t care if he’s a stevedore and hasn’t a penny in the world. Oh, by the way, Uncle Paterson, mother says that if I marry anyone unsuitable while I’m in England, she will hold you strictly responsible. I thought you’d like to know.”

“Ring off!” cried Mr. Frisby, with extraordinary vehemence.

He replaced the receiver with a bang, looked at his cuffs as if contemplating a short character-sketch of his niece, felt unequal to the effort, and took another pepsine tablet instead. He cupped his chin in his hands, and stared before him into a future that was now darker than ever.

He remembered bitterly that when his sister had married, he had been glad. He had put on an infernally uncomfortable suit of clothes and a stiff collar and had given her away at the altar. And he had been glad when the child Ann had been born. He had paid ungrudgingly for a silver christening-mug. And now the years had passed, and this had happened!

He knew the interpretation his sister would place on those words “strictly responsible” and “unsuitable.” And he knew how her displeasure would manifest itself, should her daughter, while ostensibly in his charge, contract a matrimonial alliance of which she did not approve. She would rush over to London and cluck at him——

Something went off in his ear like a bomb. The telephone had selected this most unsuitable moment to ring again. Mr. Frisby shied like a startled horse, and came up from the depths.

“ ’Lo?” he gasped.

“Are you they-ah?” asked a voice. It was a female voice.

“Mr. Frisby speaking,” he said, curtly.

“Oh?” said the voice. “Good morning, sir. I wonder if you could tell me if Master Berry is wearing his warm woollies?”

The financier gulped painfully.

“Could I—what did you say?”

“Isn’t that Mr. Frisby that Mr. Conway works for?”

“I have a secretary named Conway.”

“Well, would it be troubling you too much to ask him if he is wearing his warm woollies? You see, there’s quite a snap in the air for the time of year, and he was always so delicate as a child.”

If the prophet Job had entered the room at that moment, T. Paterson Frisby would have shaken his hand and said, “Old man, I know just how you must have felt.” A tortured frown darkened his brow. If there was one thing he disliked more than another in a world full of objectionable happenings, it was having his office staff get telephone calls on his personal wire. And when these calls had to do with the texture of their underclothing, the iron entered pretty deeply into his soul.

“Hold the line,” he said, in a low, strained voice.

He touched a button on the desk. This produced, first, a buzzing sound, and shortly afterwards his private secretary, who advanced into the room, looking bronzed and fit.

Few people would have taken Berry Conway for anyone’s private secretary. He did not look the part. He was lean and athletic-looking. He had the appearance of a welter-weight boxer who takes a cold bath every morning and sings in it. His face was clean-cut, and his figure slim and muscular. And Mr. Frisby, even when not feeling as dyspeptic as he did at the present moment, had always in a nebulous sort of way resented this. It subconsciously offended him that anyone circling in his orbit should look so beastly strong and well. Berry was obviously hard stuff. He could have taken Mr. Frisby up in one hand and eaten him at his leisure. And sometimes of an evening, when the day’s work was over, he regretted not having done so, for Mr. Frisby could make himself unpleasant.

He made himself unpleasant now.

“You!” he snapped. “What do you mean, having your friends call you up here? Some female lunatic wants you on the ’phone. Answer it.”

THE conversation that ensued was not a long one. The unseen lunatic spoke—urgently, if the humming of the wire was any evidence—and Berry, a dusky red in the face and a more vivid red about the ears, replied, “Of course I’m not—it’s quite a warm day—I’m all right—I’m all right, I tell you!” and put down the instrument. He looked at his employer with shame written on every feature.

“I’m very sorry, sir,” he said. “It was an old nurse of mine.”

“Nurse?”

“She used to be my nurse, and she has never been able to get it into her head that I’m not still a child.”

Mr. Frisby gulped.

“She asked me—she asked me if you were wearing your warm woollies.”

“I know.” Berry blushed hotly. “It sha’n’t occur again.”

“Are you?” asked Mr. Frisby, with pardonable curiosity.

“No,” said Berry shortly.

“Woof!” said Mr. Frisby.

“Sir?”

“It’s this darned indigestion,” explained the financier. “Have you ever had indigestion?”

“No, sir.”

Mr. Frisby eyed him malevolently.

“Oh? You haven’t, haven’t you? Well, I hope you get it—you and your nurse, too. Take a note. Niece. Lady of title. Papers.”

“I beg your pardon, sir?”

“Can’t you understand plain English?” said Mr. Frisby. “My niece is coming over from America for the London Season, and her mother wants me to put an advertisement in the papers for a lady of title to chaperon her. Can’t see what’s hard to grasp about that. Should have thought that would have been intelligible to anyone with an ounce of sense in his head. Put it in The Times and Morning Post and so on. Word it how you like.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Right. That’s all.”

Berry turned to the door. As he reached it, he paused. An idea had occurred to him. He was a kind-hearted young man, and liked, when possible, to do his daily good deed. It struck him that the opportunity had presented itself.

“Might I make a suggestion, sir?”

“No,” said Mr. Frisby.

Berry was not to be discouraged.

“I only thought that what you require might be somebody like Lady Vera Mace.”

“Who?”

“Lady Vera Mace.”

“Who’s she?”

“Lord Hoddesdon’s sister. She married a man named Mace in the Coldstream Guards.”

“How do you come to know anything about her?”

“I was at school with her nephew, Lord Biskerton. I met her once. She came down to the school one Saturday and stood us a feed. Coffee, doughnuts, raspberry vinegar, two kinds of jam, two kinds of cake, ice-cream, and sausages and mashed potatoes,” said Berry, in whose memory the episode had never ceased to be green.

It was not so green as Mr. Frisby. His sensitive stomach had turned four powerful handsprings and come to rest quivering.

“Don’t talk of such things,” he said, shuddering strongly. “Don’t mention them in my presence.”

“Very good, sir. But shall I tell Lady Vera to apply?”

“If you like. No harm in seeing her.”

“Thank you very much, sir,” said Berry.

He went immediately to the telephone in the passage, and rang up the Drones Club. As he had supposed, Lord Biskerton was still on the premises.

“Hullo?” said the Biscuit.

“This is Berry.”

“Say on, old boy,” said the Biscuit. “I’m with you. Talk quick, because you’re interrupting a rather tense game of snooker. What’s the trouble?”

“Biscuit, I think I can put you in the way of making a bit of money.”

The wire hummed emotionally.

“You can?”

“I think so.”

The Biscuit seemed to ponder.

“What do I have to do?” he asked. “I’m not much good at murder, and I’m not sure if I can forge. I’ve never tried. But I’ll do my best.”

“Old Frisby’s niece is coming over from America for the season. He wants someone to chaperon her.”

“Oh?” said the Biscuit, disappointedly. “And where do I come in? I suppose I apply for the job, cunningly disguised as a Dowager Duchess? I wish you wouldn’t interrupt a busy man with this sort of drip, Berry. It isn’t fair to raise a bloke’s hopes, only to dash——”

“You poor ass, I was thinking that this was just the sort of thing that would suit your aunt.”

“Ah!” The Biscuit’s tone changed. “I begin to follow. I begin to see the idea. A job for Aunt Vera, eh? This sounds good. I take it there’s money in this chaperoning, what?”

“Of course there is. Pots of money.”

“And she could do with it, poor, broken blossom!” said Lord Biskerton. “It’ll be like manna in the wilderness.”

“Well, ring her up and tell her about it. If it comes off, she may give you a bit of the proceeds.”

“May?” said the Biscuit. “How do you mean, may? I shall naturally insist on an exceedingly stiff commission, which you and I will, of course, split fifty-fifty—you having provided the commercial opening and I the aunt.”

“Not me,” said Berry. “I’m not in on this. I’m just Santa Claus.”

Lord Biskerton seemed stunned.

“Berry! This is noble. That’s what it is. Noble. It’s the sort of thing Boy Scouts do. What a pal! Tell me, how do the chances look of the relative landing this extraordinarily cushy job?”

“Great, if she can apply early and get in ahead of the field.”

“I’ll have her panting on the mat in half an hour.”

“Tell her to call at Pudding Lane and ask for Mr. Frisby.”

“I will. And may Heaven reward you, boy, for what you have done this day. It’s the first bit of joss that’s come the family’s way for years and years and years. I shall celebrate this. Eggs for tea to-night, my bucko!”

iii.

IF Mr. Frisby had been the sort of man who observes shades of emotion in his employés, he might have noticed in the demeanour of his private secretary at their recent encounter a certain unwonted gaiety, a brightness that was almost effervescent. Berry’s was a buoyant temperament, easily stimulated by the passing daydream, and the more he had examined the Biscuit’s counsel, the better it looked to him. It amazed him that through all these years he had never once thought of raising a little money on The Dream Come True.

Certainly, the thing had never produced enough copper to make a door-knob, but, as the Biscuit had so wisely pointed out, the world was full of mugs. The daily papers proved their existence every morning. They were all over the place, now purchasing a gold brick from some sympathetic stranger, anon rushing to give another stranger all their available assets to hold so that they might show their confidence in him.

It would not be a bad idea, he reflected, to ask his employer’s advice on the matter. T. Paterson was, he knew, mixed up in copper—he was president of Horned Toad, Inc.—and there were moments, in between his dyspeptic twinges, when he frequently became quite genial. It would be simple for a man of discernment to note the approach of one of these moments and put the necessary questions before the milk of human kindness ebbed again.

When he did find himself in Mr. Frisby’s presence again, however, it was to announce the arrival of Lady Vera Mace. The Biscuit’s aunt was not the woman to dally when there was money in the air. She arrived at three-thirty sharp.

“Lady Vera Mace is here, sir,” said Berry. “Shall I show her in?”

“Ugh.”

“And might I have a word with you later on a personal matter?”

“Ugh.”

BERRY returned to his little room and resumed his daydreams. From time to time he wondered how the interview was coming along. He hoped that the Biscuit’s aunt was clicking. She needed the money, and she had once been kind to him as a schoolboy. Besides, the Biscuit would touch his commission, which would mean happiness all round.

She ought to get the job, he reflected. The passage of time, though it had prevented her recognizing him just now and resuming their ancient friendship, had been in other respects kind to Lady Vera Mace. She was still the rather formidably beautiful woman who had come down to the school years ago and stuffed him with food. Her voice was soft and silvery, her manner compelling. Unless he was greatly mistaken, she would rush T. Paterson off his feet and have him gasping for air in the first minute.

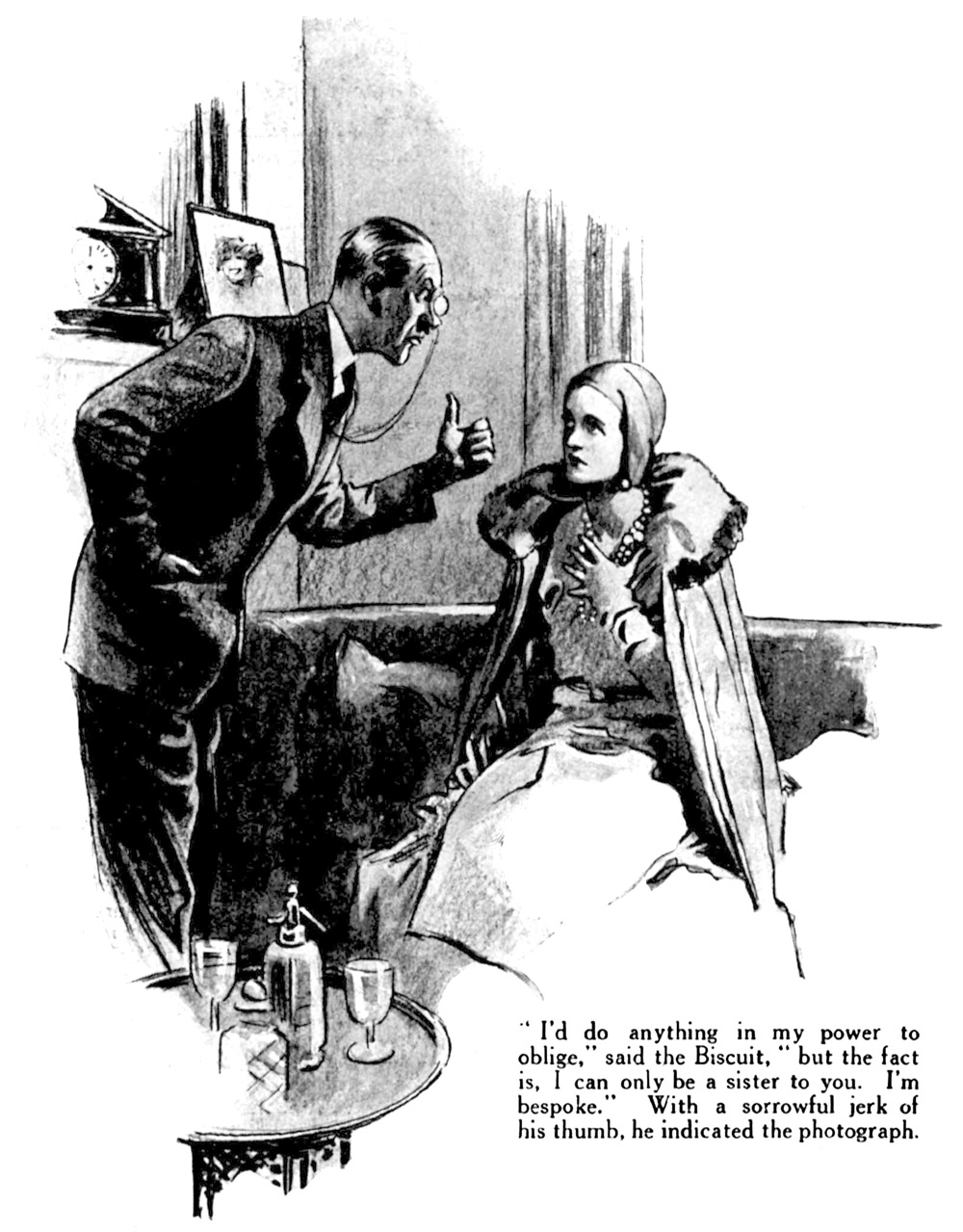

The sound of the buzzer broke in on his meditations. Answering its summons, he found his employer alone. T. Paterson Frisby was leaning back in his swivel-chair, looking, as far as a great financier ever can do, rather fatuous. An unwonted smile was on his lips, and it was a foolish smile. Also, there was a rose in his buttonhole which had not been there before.

“Eh?” he said, starting, as Berry entered.

“Yes, sir?”

“What do you want?”

“What do you want, sir? You rang.”

Mr. Frisby seemed to come out of a trance.

“Oh, yes. Take a note.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Pim’s. Friday.”

“Sir?”

“I’m giving Lady Vera Mace lunch at Pim’s on Friday,” translated Mr. Frisby. “She wants to see the Stock Exchange.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And those advertisements. Don’t put ’em in. Not needed.”

“No, sir.”

“I have arranged with Lady Vera that she will chaperon my niece when she arrives.”

“Yes, sir.”

Mr. Frisby seemed to return to his trance-like state. His eyes had half closed and he looked, though still pickled, almost human.

“That’s a remarkable woman,” he murmured. “She’s done my dyspepsia good.”

“Yes, sir?”

“She said it was mainly mental,” proceeded Mr. Frisby. He gave the impression of one soliloquizing with no thought of an audience. “She said drugs are no use. What one ought to do, she said, is think beautiful thoughts. Let sunshine into the soul, she said. She said, ‘Imagine that you are a little bird on a tree. What would you do? You would sing. So——’ ”

He broke off. The shock of imagining himself a little bird on a tree appeared to have roused him to a sense of his position.

“Well, she’s a very remarkable woman,” he said, almost defiantly. He blinked at Berry. “What was that you were saying just now? Something about wanting to see me about something? What is it?”

“It’s about a mine, sir. A mine in which I am interested.”

“What sort of mine?”

“A copper mine.”

Mr. Frisby’s geniality became frosted over with a thin covering of ice.

“Have you been taking a flyer in copper?” he asked, dangerously. “Let me tell you here and now, young man, that I won’t have my office staff playing the market.”

Berry hastened to reassure him.

“I haven’t been speculating,” he said. “This mine is mine. A mine of my own. My mine. It belongs to me. I own it.”

“Don’t be a damned fool,” said Mr. Frisby, severely. “How the devil can you own a mine?”

“My aunt left it to me.”

For the second time that day, Berry sketched out his family history.

“Oh, I see,” said Mr. Frisby, enlightened. “Where is this mine?”

“Somewhere in Arizona.”

“What’s it called?”

“The Dream Come True,” said Berry, uncomfortably. He was wishing that its original owner, in christening his property, had selected a name less reminiscent of a theme song.

“The Dream Come True?”

“Yes.”

Mr. Frisby sat forward in his chair and stared at his fountain-pen. He seemed to have fallen into a trance again.

“It has never produced any copper,” Berry went on in a rather apologetic voice. “But I was talking to a man at lunch, and he said that if one looked round one could always find someone to buy a mine.”

Mr. Frisby came to life.

“Eh?”

Berry repeated his remarks.

Mr. Frisby nodded.

“So you can,” he said, “if you pick the right sort of boob. And there’s one born every minute.”

“I was wondering if you could advise me as to the best way of setting about——”

“You say this mine has never yielded?”

“No.”

“Well, you can’t expect to get much for it, then.”

“I don’t,” said Berry.

Mr. Frisby took up his fountain-pen, gazed at it, and put it down again.

“Well, I’ll tell you,” he said. “Oddly enough, I know a man—Hoke’s his name. J. B. Hoke. He might make you an offer. He does quite a bit in that line. Buys up these derelict properties on the chance of some day striking something good. If you like, I’ll get in touch with him.”

“Thank you very much, sir.”

“I believe he’s in America just now. I’ll have to find out. Of course, he wouldn’t look at the thing unless he could get it cheap. Well, anyway, I’ll get in touch with him.”

“Thank you very much, sir.”

“You’re welcome,” said Mr. Frisby.

Berry withdrew. Mr. Frisby took up the receiver and called a number.

“Hoke?” he said. “Frisby speaking.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby?” replied a voice, deferentially.

It was a fat and gurgly voice. Hearing it, you would have conjectured that its owner had a red face and weighed a good deal more than he ought to have done.

“Want to see you, Hoke.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby. Shall I come to your office?”

“No. Grosvenor House. About six.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“Be on time.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

iv.

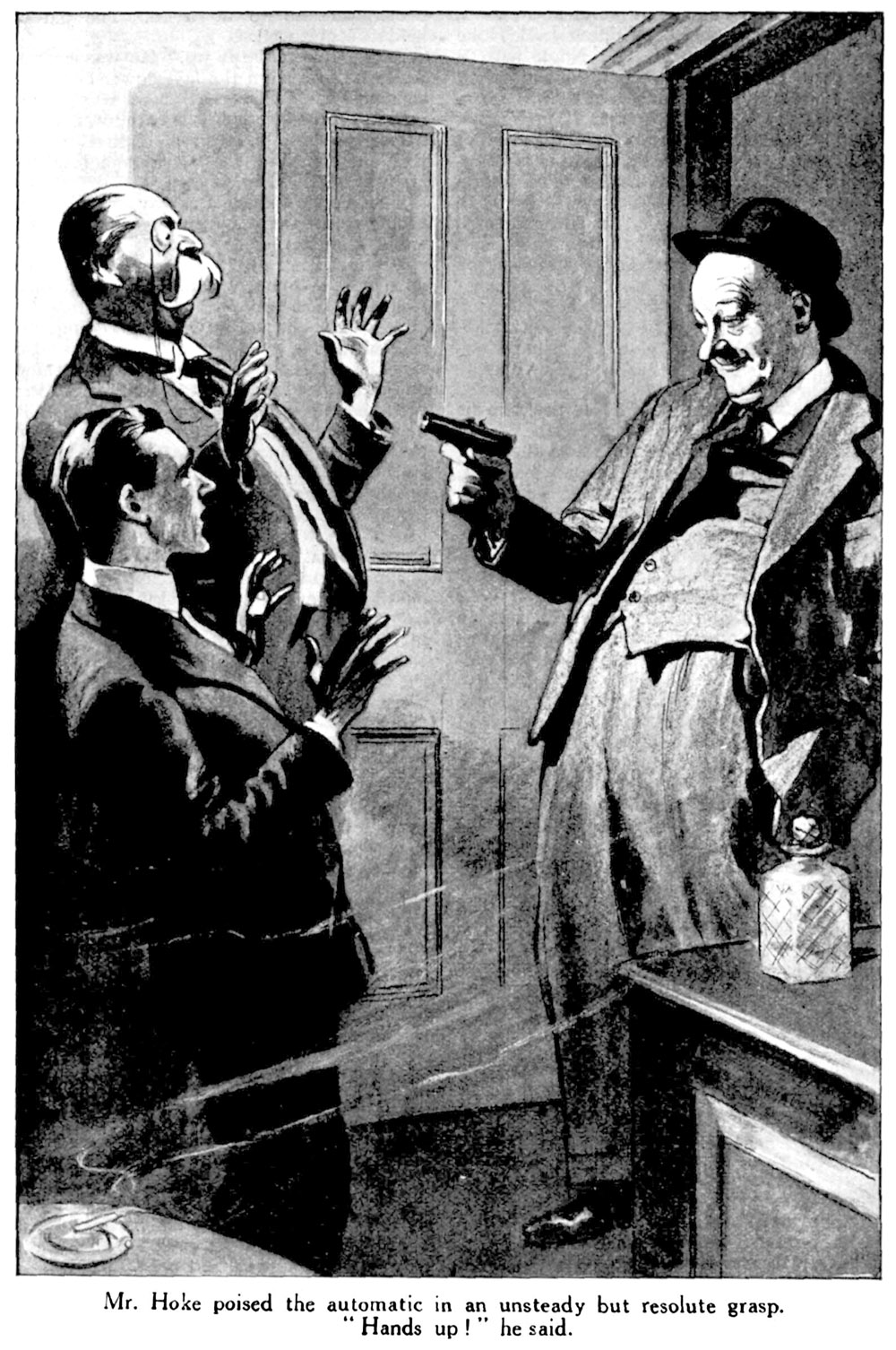

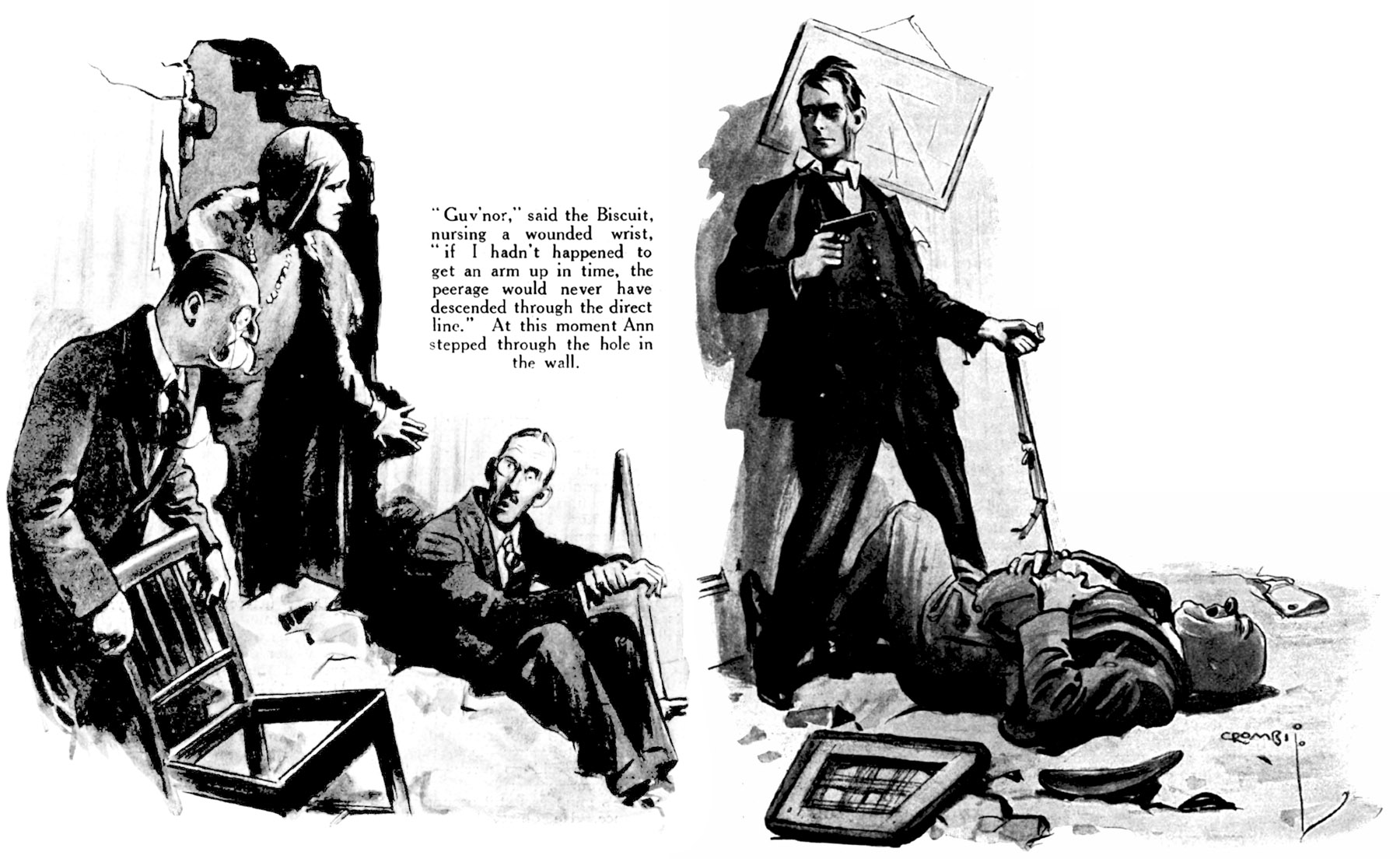

PEOPLE summoned by Mr. Frisby to interviews in his apartment at Grosvenor House always exhibited a decent humility. They seemed to indicate by their manner how clearly they realized that in this inner shrine they were standing on holy ground. The red-faced man who had entered the sitting-room at six precisely almost grovelled.

J. B. Hoke was one of those needy persons who exist on the fringe of the magic world of finance and eke out a precarious livelihood by acting as Yes-men-in-ordinary to any of the great financiers who may wish to employ them. Willingness to oblige was Mr. Hoke’s outstanding quality. He would go anywhere you sent him, and do anything you told him to do.

“Good evening, Mr. Frisby,” said J. B. Hoke. “How are you?”

“Never mind how I am,” said Mr. Frisby. “Got something I want you to do for me.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby?”

“You know I’m President of the Horned Toad Copper Corporation?”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“Well, next door to it there’s a small claim called The Dream Come True. It’s been derelict for years.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby?”

“I’ve had a letter from my directors. They seem to want to take it over for some reason. We’re putting in some developments on the Horned Toad, and maybe they need the ground for workmen’s shacks, or something. They didn’t say. I want you——”

“To trace the owner, Mr. Frisby?”

“Don’t interrupt,” said T. Paterson, curtly. “I know the owner. The thing belongs to my secretary, a man named Conway. He was left it by someone, he tells me. I want you to go to him and buy it for me. Cheap.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“I can’t appear in the matter myself. If young Conway thought that Horned Toad Copper was after his property, he’d stick his price up at once.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“And there’s no hurry about buying it. I told him I would mention it to you, and I said you were in America. You don’t want to seem too eager. I’ll tell you when to shoot.”

“Yes, Mr. Frisby.”

“Right. That’s all.”

T. Paterson Frisby gave a Napoleonic nod, to indicate that the interview was concluded, and J. B. Hoke, just falling short of knocking his forehead on the floor, retired.

Having left the presence, Mr. Hoke went downstairs and turned into the passage leading to the American bar. A man who was sitting on a stool, sipping a cocktail, got up as he entered.

“Well?” he said.

He eyed Mr. Hoke woodenly. He was one of those excessively smoothly-shaved men of uncertain age and expressionless features whom one associates at sight with the racing world. It was on a race-course that J. B. Hoke had first made his acquaintance. His name was Kelly, and in the circles in which he moved he was known as Captain Kelly, though in what weird regiment of irregulars he had ever held a commission nobody knew.

He drew Mr. Hoke into a corner, and once more inspected him with a wooden stare.

“What did he want?” he asked.

J. B. Hoke’s manner had undergone a change for the worse since leaving Mr. Frisby’s sitting-room. His gentle suavity had disappeared.

“The old devil,” he said, disgustedly, “simply wanted me to act as his agent in buying up some derelict copper mine somewhere.”

He chewed a toothpick morosely, for Mr. Frisby’s summons had excited him and aroused hopes of large commissions. He had come away a disappointed man.

“What does he want with a derelict mine?” asked Captain Kelly, his fathomless eyes still fixed on his companion’s face.

“Says it’s next door to his Horned Toad,” grunted Mr. Hoke, “and they want the ground for putting up workmen’s shacks.”

“H’m!” said Captain Kelly.

“He didn’t need me. An office-boy could have done all he wanted. Wasting my time!” said J. B. Hoke.

“Sounds thin to me,” said the Captain.

“What does?”

“What he says he wants that property for.”

“Seemed all right to me.”

“Ah, but you’re a fool,” the Captain pointed out, dispassionately. “If you want to know what I think, I’d say at a guess that a new reef of copper had been discovered.”

“Not on this claim,” said Mr. Hoke. “I happen to know the one he means. I was all over those parts a few years ago. I know this Dream Come True, which is its fool name. A fellow named Higginbottom, a prospector from Burr’s Crossing, staked it out a matter of ten years back. And from that day to this no one’s ever had an ounce of copper out of it. I shouldn’t say it had ever been worked after the first six months.”

“But they’ve been working the Horned Toad.”

“Of course they’ve been working the Horned Toad.”

“Suppose they had struck a vein and found that it went on into this property next door?”

“Chee!” said Mr. Hoke, his none-too-active brain stirring for the first time.

“I’ve heard of cases.”

“I’ve heard of cases,” said Mr. Hoke.

He stared at his companion emotionally. Rainbow visions had begun to rise before him.

“I believe you’re right,” he said.

“That’s the way it looks to me.”

“There may be big money in this!”

“Ah!” said the Captain.

“Now, see here——” said Mr. Hoke.

He lowered his voice cautiously and began to talk business. From time to time Captain Kelly nodded wooden approval.

CHAPTER II.

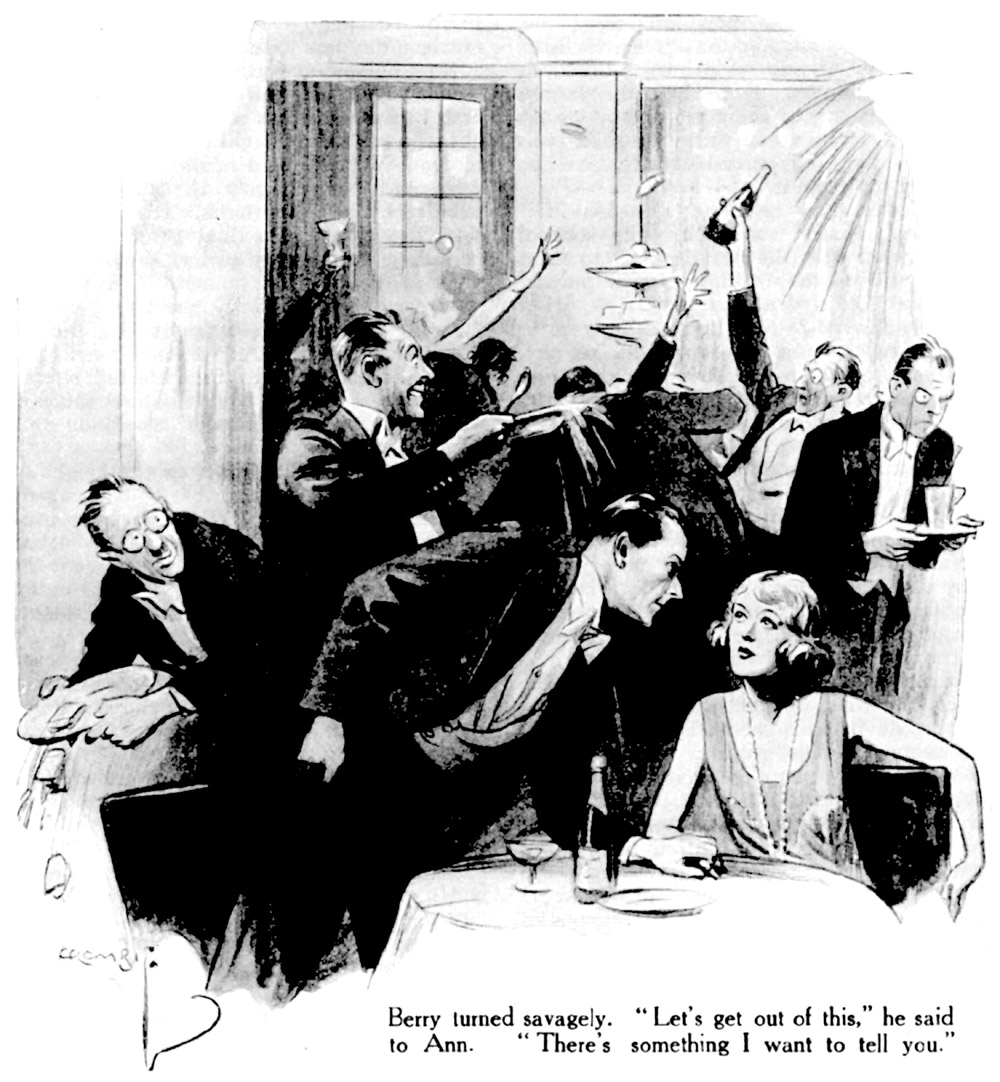

AND so, in due course, in the blue-and-apricot twilight of a perfect May evening, Ann Moon arrived in England with a hopeful heart and ten trunks and went to reside with Lady Vera Mace at her cosy little flat in Davies Street, Mayfair. And presently she was busily engaged in the enjoyment of all the numerous amenities which a London Season has to offer.

She lunched at the Berkeley, tea-ed at Claridge’s, dined at the Embassy, supped at the Kit-Kat.

She went to the Cambridge May Week, the Buckingham Palace Garden Party, the Aldershot Tattoo, the Derby, and Hawthorn Hill.

She danced at the Mayfair, the Bat, Sovrani’s, the Café de Paris, and Bray on the river.

She spent week-ends at country-houses in Bucks, Berks, Hants, Lincs, Wilts, and Devon.

She represented an Agate at a Jewel Ball, a Calceolaria at a Flower Ball, Mary Queen of Scots at a Ball of Famous Women Through the Ages.

She saw the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, Madame Tussaud’s, Buck’s Club, the Cenotaph, Limehouse, Simpson’s in the Strand, a series of races between consumptive-looking greyhounds, another series of races between goggled men on motor-cycles, and the penguins in St. James’s Park.

She met soldiers who talked of horses, sailors who talked of cocktails, poets who talked of publishers, painters who talked of sur-realism, absolute form, and the difficulty of deciding whether to be architectural or rhythmical.

And at an early point in her visit she met Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, and one Sunday morning was driven down by him in a borrowed two-seater to inspect the ancestral country seat of his family, Edgeling Court, in the county of Sussex.

They took sandwiches and made a day of it.

CHAPTER III.

THERE are those who maintain that the inhabitants of Great Britain are a cold, impassive race, not readily stirred to emotion, and that to get real sentiment you must cross the Atlantic. These would have solid support for their opinion in the sharply-contrasting methods employed by The Courier-Intelligencer of Mangusset, Maine, and its older-established contemporary, The Morning Post, of London, Eng., in announcing—some six weeks after the date on which this story began—the engagement of Ann Moon to Lord Biskerton.

Mangusset was the village where Ann’s parents had their summer home, and the editor of The Courier-Intelligencer, whose heart was in the right place and who had once seen Ann in a bathing suit, felt—justly—that something a little in the lyrical vein was called for. This, accordingly, was the way in which he hauled up his slacks—and he did it—which makes it all the more impressive—entirely on buttermilk. For, though the evidence seems all against it, he was a lifelong abstainer.

“The bride-to-be (wrote ye Ed.) is a girl of wondrous fascination and remarkable attractiveness, for with manner as enchanting as the wand of a siren, and disposition as sweet as the odour of flowers, and spirit as joyous as the carolling of birds, and mind as brilliant as those glittering tresses that adorn the brow of winter, and with heart as pure as dewdrops trembling in a coronet of violets, she will make the home of her husband a Paradise of enchantment like the lovely home of her girlhood, so that the heaven-toned harp of marriage, with its chords of love and devotion and fond endearments, will send forth as sweet strains of felicity as ever thrilled the senses with the rhythmic pulsing of ecstatic rapture.”

The Morning Post, in its quiet, hard-boiled way, confined itself to a mere recital of the facts. No fervour. No excitement. Not a tremor in its voice. It gave the thing out as unemotionally as on another page it had stated that the boys and girls of Birchington Road School, Crouch End, had won the championship and challenge cup for infant percussion bands at the North London Musical Festival held in Kentish Town.

Thus:—

MARRIAGE ANNOUNCEMENTS.

“The engagement is announced between Lord Biskerton, son and heir of the Earl of Hoddesdon, and Ann Margaret, only child of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas L. Moon, of New York City.

Sub-editors get that way in London. After a few years in Fleet Street they become temperamentally incapable of seeing any difference between a lot of infants tootling on trombones and a man and a maid starting out hand-in-hand on the long trail together. If you want to excite a sub-editor, you must be a mystery fiend and slay six with hatchet.

But if The Morning Post was blasé, plenty of interest was aroused among the public that supports it. In a hundred beds a hundred young men stopped sipping a hundred cups of tea in order to give that notice their undivided attention. To some of these the paragraph had a sinister and an ominous ring. They concentrated their minds, such as they were, on the frightful predicament of the bridegroom-elect; and, muttering to themselves “My God!” turned to the Racing page with an uneasy feeling that nowadays no man was safe.

But there were others—and these formed a majority—who sank back on their pillows and stared wanly at the ceiling—silk-pyjama-clad souls in torment. They mused on the rottenness of everything, reflecting how rotten, if you came right down to it, everything was. They pushed aside the thin slice of bread-and-butter; and when their gentleman’s personal gentlemen entered babbling of spats, were brusque with them—in eleven cases telling them to go to the devil.

For these were the young men who had danced with Ann and dined with Ann and taken Ann to see the penguins in St. James’s Park. Ann Moon, in her progress through the London Season, had undoubtedly made her presence felt. A girl cannot go about the place for a month and a half with a manner as enchanting as the wand of a siren without bruising a heart or two.

In the dining-room of The Nook, Mulberry Grove, Valley Fields, S.E.21, Berry Conway came on the notice while skimming the paper preparatory to the morning dash for London on the 8.45. He was finding some difficulty in reading, owing to the activities of the old retainer, who had a habit of drifting in and out of the room during breakfast, issuing the while a sort of running bulletin of matters of local interest.

MRS. WISDOM was plump and comfortable. She gazed at Berry with stolid affection, like a cow inspecting a turnip. To her, he was still the infant he had been when they had first met. Her manner towards him was always that of wise Age assisting helpless Youth through a perplexing world. She omitted no word or act that might smooth the path for him and shield him against life’s myriad dangers. In winter she thrust unwanted hot-water bottles into his bed. In summer she would speak freely, not mincing her words, of flannel next to the skin and of the wisdom of cooling off slowly when the pores had been opened.

“Major Flood-Smith,” said the old retainer, alluding to the retired warrior resident at Castlewood, next door but one, “was doing Swedish exercises in his garden early this morning.”

“Yes?”

“And the cat at Peacehaven had a sort of fit.”

Berry speculated absently on the mysteries of cause and effect.

“I hear Mr. Bolitho’s firm are sending him to Manchester. Muriel-at-Peacehaven told me. He wants to let Peacehaven furnished. I think he ought to put an advertisement in the papers.”

“Not a bad idea. Ingenious.”

Something in the passage attracted Mrs. Wisdom’s attention. She drifted out, and Berry heard umbrella-stands falling over. Presently she drifted in again.

“After the Major had gone, his niece came out and picked some flowers. A sweetly pretty girl, I always say she is.”

“Yes?”

“And what’s funny is, she was looking quite happy.”

“Why was that funny?”

“Why, Master Berry! Surely I told you about her? Her sad story?”

“I don’t think so,” said Berry, turning the pages. She probably had, he thought, but she told him so much local gossip—taking, as she did, a ghoulish relish in every disaster that happened to everybody in the suburb—that he had developed a protective deafness.

Mrs. Wisdom clasped her hands and threw up her eyes, the better to do justice to the big scoop.

“Well, really, I can’t imagine how I came not to tell you. I had it all from Gladys-at-Castlewood, and she got it partly by listening while waiting at table and the rest of it one evening when the young lady came down to the kitchen and wanted to know if the cook could make something she called fudge, and then she stayed on herself and made this fudge, which seems to be a sort of soft toffee, and told them her sad story while stirring up the sugar and butter.”

“Ah?” said Berry.

“The young lady has come over from America. Her mother is the Major’s sister, who married an American, and they live in a place near New York which is called, though you can hardly believe it, Great Neck. Well, I mean, what a name to call a place. And Great Neck, it seems, Master Berry, is full of actors, and the young lady, her name is Katherine Valentine, was foolish enough to think she had fallen in love with one of them and wanted to marry him, and he wasn’t anybody really, as he only acted small parts, and her father, of course, was furious, and he sent her over here to stay with the Major in the hope that she might be cured of her infatuation.”

“Ah?” said Berry. “Good Lord! Look at this! The Biscuit has gone and jumped off the dock! Biskerton. Fellow I was at school with.”

“Committed suicide?” cried Mrs. Wisdom, delightedly. “How dreadful!”

“Well, not exactly suicide. He’s engaged to be married. To an American girl. Ann Margaret, only child of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas L. Moon, of New York.”

“Moon?” Mrs. Wisdom wrinkled her forehead. “Now I wonder if that is the same young lady Gladys-at-Castlewood told me Miss Valentine told her about. Miss Valentine travelled over on the boat with a Miss Moon, and I feel sure Gladys told me that she told her that her name was Ann. They became great friends. Miss Valentine told Gladys that her Miss Moon was a very nice young lady. Very pretty and attractive.”

“The Morning Post doesn’t mention that. Still, if she’s pretty and attractive, I may be wronging the Biscuit in thinking he is selling himself for gold.”

“Why, Master Berry! What a thing to say of a friend of yours!”

“Well, it’s a bit of luck for him, anyway. I suppose this girl is rolling in money.”

“I hope you won’t ever marry for money, dear.”

“Not me. I’m romantic. I’m one of those fellows who are practically all soul.”

“I often say it’s love that makes the world go round.”

“I’ve never heard it put as well as that before,” said Berry, “but I shouldn’t wonder if you weren’t absolutely right. Was that the clock striking? I must rush.”

George, sixth Earl of Hoddesdon, father of the bridegroom-to-be, did not see his Morning Post till nearly eleven. He was a late riser and paper-reader. Having scanned the announcement with silent satisfaction, fingering at intervals the becoming grey moustache which adorned his upper lip, he put on a grey top-hat and went round to see his sister, Lady Vera Mace.

“ ’Morning, Vera.”

“Good morning, George.”

“Well, I see it’s in.”

“The announcement? Oh, yes.”

Lord Hoddesdon eyed her reverently.

“It’ll be the first time the family has seen the colour of real money,” he said, “since the reign of Charles the Second.”

There was a pause.

“George,” said Lady Vera.

“Hullo?”

“I want you to attend to me very carefully, George.”

Lord Hoddesdon surveyed his sister almost affectionately. He was seeing everything through rose-coloured spectacles on this morning of mornings; but, even making the necessary allowances for that, he was bound to admit that she looked extraordinarily attractive. Upon his word, felt Lord Hoddesdon, she seemed to get handsomer all the time. He made a mental calculation. Yes, well over forty, and anyone might take her for thirty-two. A thrill of pride passed through him, heightened as he caught sight of his own reflection in the mirror. Whatever you might say about them, the family did keep their looks.

His second thought was that, much as he admired the flawless regularity of his sister’s features, he was not at all sure that he liked the expression they were wearing at the moment. An odd expression. Rather hard. She reminded him of a governess who had rapped his knuckles a good deal when he was a child.

“I want you to remember, George, that they are not married yet.”

“Of course. Naturally not. Announcement’s only just appeared in the paper.”

“And so will you please,” proceeded Lady Vera, her beautiful eyes now definitely stony, “abandon your intention of calling on Mr. Frisby and asking him to oblige you with a small loan. It is just the sort of thing that might upset everything.”

Lord Hoddesdon gasped.

“You don’t imagine I would be fool enough to go touching Frisby?”

“Wasn’t that your idea?”

“Of course not. Certainly not. I was thinking—er—I was wondering—well, to tell you the truth, it crossed my mind that you might possibly be willing to part with a trifle.”

“It did, eh?”

“I don’t see why you shouldn’t,” said Lord Hoddesdon, plaintively. “You must have plenty. There’s a lot of money in this chaperoning business. When you took on that Argentine girl three years ago, you got a couple of thousand pounds.”

“I got fifteen hundred,” corrected his sister. “In a moment of weakness—I can’t imagine what I was thinking of—I lent you the rest.”

“Er—well, yes,” said Lord Hoddesdon, not unembarrassed. “That is, in a measure, true. It comes back to me now.”

“It didn’t come back to me—ever,” said Lady Vera, in a voice that sounded, though not to her brother, like the tinkling of silver bells.

There was another pause.

“Oh, well, if you won’t, you won’t,” said Lord Hoddesdon, gloomily.

“No,” agreed Lady Vera. “But I’ll tell you what I will do. I was going to take Ann to lunch at the Berkeley, but Mr. Frisby has rung up to ask me to motor down to Brighton for the day; so I will give you the money and you can look after her.”

Lord Hoddesdon felt a little like a tiger which has hoped for a cut off the joint and has been handed a cheese-straw, but he told himself, with the splendid Hoddesdon philosophy, that it was better than nothing.

“All right,” he said. “I’m not doing anything. Hand over the tenner.”

“The what?”

“Well, the fiver, or whatever it may be.”

“Lunch at the Berkeley,” said Lady Vera, “costs eight shillings and sixpence. For two, seventeen shillings. Waiter, two shillings. Possibly Ann may like a lemonade or some water of some kind. Say two shillings again. Your hat-check sixpence. For coffee and unforeseen emergencies, half a crown. If I give you twenty-five shillings, that will be ample.”

“Ample?” said Lord Hoddesdon.

“Ample,” said Lady Vera.

Lord Hoddesdon fingered his moustache unhappily. He was feeling now as Elijah would have felt in the wilderness if the ravens had suddenly developed cut-throat business methods.

“But suppose the girl wants a cocktail?”

“She doesn’t drink cocktails.”

“Well, I do,” said Lord Hoddesdon, mutinously.

“No, you don’t,” said Lady Vera, her resemblance to the departed governess now quite striking.

Lord Biskerton was not a reader of The Morning Post. The first intimation he received that the announcement of his betrothal had appeared in print was when Berry Conway rang him up from Mr. Frisby’s office to congratulate him. He accepted his friend’s good wishes in a becoming spirit and resumed his breakfast in a quiet and orderly manner.

He was busy on the marmalade when his father arrived.

IT was not often that Lord Hoddesdon visited his son and heir, but in some mysterious way there had floated into his lordship’s mind as he left Lady Vera’s flat the extraordinary idea that Biskerton might possibly have a little cash in hand and be willing to part with some of it to the author of his being.

“Er—Godfrey, my boy.”

“Hullo, guv’nor!”

Lord Hoddesdon coughed.

“Er—Godfrey,” he said, “I wonder—it so happens that I am a little short at the moment—I suppose you could not possibly——”

“Guv’nor,” said the Biscuit, amusedly, “this is To-day’s Big Laugh. Don’t tell me you’ve come to make a touch?”

“I thought——”

“What on earth led you to suppose I’d got a bean?”

“I fancied that possibly Mr. Frisby might have made you some small present.”

“Why the dickens?”

“In celebration of the—er—happy event. After all, he is the uncle of your future bride. But, of course, if such is not the case——”

“Such,” the Biscuit assured him, “is decidedly not. The old moth-eaten fossil to whom you allude, guv’nor, is the one man in this great city who never makes small presents in celebration of any happy event. His family motto is Nil desperandum—Never give up.”

“Too bad,” sighed Lord Hoddesdon. “I was hoping that you would be able to help me out. I am sorely in need of monetary assistance. Your aunt has asked me to take your fiancée to lunch at the Berkeley this afternoon, and her idea of expense-money is little short of Aberdonian. Twenty-five shillings!”

“Lavish,” said the Biscuit, firmly. “I wish somebody would give me twenty-five bob. I’ve just a quid to see me through to the end of the month.”

“As bad as that?”

“One pound two and twopence, to be exact.”

“Still,” Lord Hoddesdon pointed out, “you must remember that your prospects are now of the brightest. You have been wiser in your generation than I in mine, my boy.” He stroked his moustache and heaved another regretful sigh. “As a young man,” he said, “my great fault was impulsiveness. I should have married money, as you are so sensibly doing. How clearly I see that now! And I had my opportunity—opportunity pressed down and running over. For months after I succeeded, wall-eyed heiresses were paraded before me in droves. But I was too romantic, too idealistic. Your poor mother was at that time a humble unit of the Gaiety Theatre company, and after I had been to see the piece in which she was performing sixteen times I suddenly noticed her. She was standing on the extreme O.P. side. Our eyes met—— Not that I regret it for a moment, of course,” said Lord Hoddesdon. “As fine a pal as a man ever had. On the other hand—— Yes, you have shown yourself a wiser man than your old father, my boy.”

SEVERAL times during this address the Biscuit had given evidence of a desire to interrupt. He now spoke forcefully.

“I wish you wouldn’t talk of Ann and wall-eyed heiresses without taking a long breath in between,” he said, justly annoyed. “When you say I’m marrying money, it makes it sound as if the cash was all I cared about. Let me tell you, guv’nor, that this is love. The real thing. I’m crazy about Ann. In fact, when I think that a girl can be such a ripper and at the same time be so dashed rich, it restores my faith in the Providence which looks after good men. She’s the sweetest thing on earth, and if I had more than one pound two and twopence I’d be taking her to lunch to-day myself.”

“A charming girl,” agreed Lord Hoddesdon. “How did you ever induce her to accept you?” he asked, a father’s natural bewilderment returning.

“It was Edgeling that did it.”

“Edgeling?”

“Edgeling. You may say what you like against our old ancestral seat, guv’nor—it costs a fortune to keep up and it’s too big to let and a white elephant generally, but there’s one thing about it—it’s romantic. I proposed to Ann in the old bowling-green—we had driven down in Pobby Blaythwaite’s two-seater—and it’s my belief there isn’t a girl in the world who could have held out in a setting like that. Doves were cooing, bees were buzzing, rooks were cawing, and the setting sun was gilding the ivied walls. No girl could have refused a fellow in such surroundings. Believe me, whatever its faults, Edgeling has done its bit and deserves credit.”

“And talking of credit,” said Lord Hoddesdon, “it is pleasant to think that yours will now be excellent.”

The Biscuit laughed bitterly.

“Don’t you imagine it for an instant,” he said vehemently. He indicated a pile of papers on the table. “Look at those.”

“What are they?”

“Judgment summonses. If I hadn’t a good, level head, I’d be in the County Court to-morrow.”

Lord Hoddesdon uttered a startled cry.

“You don’t mean that!”

“I do. Those fellows are out for blood. Shylock was a beginner compared with them.”

“But, good God! Have you reflected? Do you realize? If you are taken into court, your engagement will be broken off. It is just the sort of thing that would appal a man like Frisby.”

The Biscuit held up a soothing hand.

“Have no fear, guv’nor. I have the situation well taped out. Trust me to take precautions. Look here.”

He went to a drawer, took something out, concealed himself for a swift instant behind the angle of the bookcase, and emerged. And as he did so Lord Hoddesdon emitted a strangled cry.

He might well do so. Except for the fact that he possessed his mother’s hair, Lord Biskerton’s appearance had never appealed strongly to the sixth Earl’s æsthetic sense. And now, with a dark wig covering that hair and a black beard of Imperial cut hiding his chin, he presented a picture so revolting that a father might be excused for making strange noises.

“Bought ’em at Clarkson’s yesterday,” said the Biscuit, regarding himself with satisfaction in the mirror. “On tick, of course. Some eyebrows go with them. How about it?”

“Godfrey! My boy.” Lord Hoddesdon’s voice trembled, as a man’s will in moments of intense emotion. “You look terrible. Shocking. Ghastly. Like an international spy or something. Take the beastly things off!”

“But would you recognize me?” persisted his son. “That’s the point. If, say, you were Hawes and Dawes, Shirts, Ties, and Linens, twenty-three pounds four and six, would you imagine for an instant that beneath this shrubbery Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, lay hid?”

“Of course I should.”

“I’ll bet you wouldn’t. No, not even if you were Dykes, Dykes, and Pinweed, Bespoke Tailors and Breeches-Makers, eighty-eight pounds five and eleven. And I’ll tell you how I’ll prove it. You say you and Ann are lunching at the Berkeley. I’ll be there, too, at a table as near yours as I can manage. And if Ann lets out so much as a single ‘Heavens! It is my Godfrey!’ I’ll call a waiter, give him beard, wig, and eyebrows, instruct him to have them fricasseed, and eat them.”

Lord Hoddesdon uttered a faint moan and shut his eyes.

(To be continued.)

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine, p. 349b, had “Berry’s a buoyant temperament”; ‘was’ inserted.

Magazine, p. 354a, had “only child of Mrs. and Mrs. Thomas L. Moon”; changed to “Mr. and Mrs.”

—————

The Strand Magazine, November 1930

THE FIRST CHAPTERS.

Berry Conway’s only assets are a copper mine, of no account, and a longing for Adventure, unrealizable so long as he lives with his old nurse in the suburb of Valley Fields. Berry is the secretary of T. Paterson Frisby, an American financier. For his own reasons, Frisby, who owns a mine alongside Berry’s, is anxious to buy Berry’s through the intermediary of a hanger-on named Hoke. Frisby’s niece, Ann Moon, has become engaged to Berry’s friend, Lord Biskerton (“the Biscuit”), the creditor-harried son of the equally hard-up Lord Hoddesdon. Lord Hoddesdon’s sister, Lady Vera Mace, is chaperoning Ann Moon during her stay in London. “That’s a remarkable woman,” says Frisby of Lady Vera, and arranges to motor her to Brighton on the day the engagement of Ann and “the Biscuit” is announced. With a mere twenty-five shillings given him by Lady Vera for the purpose, Lord Hoddesdon prepares to take Ann Moon to the Berkeley to lunch. “The Biscuit” is so beset by his creditors that he dare not appear in public unless heavily disguised in a false beard.

CHAPTER IV.

i.

WITH his usual masterful dash in the last fifty yards, Berry Conway had beaten the eight-forty-five express into Valley Fields station by the split-second margin which was his habit. And it was only after he had taken his seat and regained his breath, and had leisure to look about him, that he realized how particularly pleasant this particular day was.

It was, he perceived, a day for joy and adventure and romance. The sun was shining from a sapphire sky. Under its rays Herne Hill looked quite poetic. So did Loughborough. And the river, as he crossed it, positively laughed up at him. By the time he reached Pudding Lane, he had come definitely to the conclusion that this was a morning which it would be a crime to waste cooped up in a stuffy office.

He had frequently felt like this before, but never had Mr. Frisby appeared to see eye to eye with him. Hard, prosaic stuff had gone to the making of T. Paterson Frisby. You didn’t find him flinging work to the winds, and going out and dancing Morris Dances in Cornhill just because the sun happened to be shining.

But miracles do happen, if one is patient and prepared to wait for them. Just as Berry had finished sorting as dull a collection of letters as ever offended a young man’s sensibilities on a glowing summer day, the door was flung open, and there came in something so extraordinarily effulgent that he had to blink twice before he could focus it.

It was not merely that T. Paterson Frisby was wearing a suit of light grey flannel. It was not even the fact that he had a panama hat on his head and a Brigade of Guards tie round his neck that stupefied the observer. The really amazing thing about him was his air of radiant bonhomie. The man seemed positively roguish. He had gone gay. As Berry stared at him dumbly, a sort of spasm passed over T. Paterson Frisby’s face, causing a hideous distortion. It was a smile.

“ ’Morning, Conway!”

“Good morning, sir,” said Berry, blankly.

“Anything in the mail?”

“Nothing of importance, sir.”

“Well, leave it all till to-morrow.”

“Till to-morrow?”

“Yes. I’m off to Brighton.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You can take the day off.”

“Thank you very much, sir,” said Berry.

He was stunned. Such a thing had never happened before. Not once in the whole course of his association with Mr. Frisby had there ever been even the suggestion of such a thing. He could hardly believe that it was happening now.

“Got to start right away. Motoring. Sha’n’t be back till this evening. Two things I want you to do. Go to Mellon and Pirbright in Bond Street, and get me a couple of gangway seats for some good show to-night. Put them down to my account, and have them sent to my apartment.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Tell them I want something good. They know what I’ve seen. And then go on to the Berkeley, and book me a table for supper.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Table for two. Not too near the band.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Right. By the way, I knew there was something. I saw that man Hoke last night. I told him about that mine of yours. He’s interested.”

A thrill shot through Berry.

“Is he, sir?”

“Yes. Oddly enough, he happens to know that particular property. Will you be in this evening?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’ll tell him to run down and see you. Between ourselves—don’t let him know I told you—he will go to five hundred pounds.”

“He will!”

“He told me so. He was going to have tried for less, but I said that that was your lowest figure. So, if you’re satisfied, he’ll bring down all the papers and you can get the thing settled to-night. And I won’t charge you agent’s commission,” said Mr. Frisby, chuckling like a Cheeryble brother, and took his departure.

For some moments after he had gone, Berry remained motionless. Motionless, that is to say, as far as his limbs were concerned. His brain was racing tempestuously.

Five hundred pounds! It was the key to life and freedom. Attwater’s loan—he could repay that. The Old Retainer—he could fix her up so that she would be all right. And, when these honourable duties were performed, he would still have something in pocket to start him off on the path of Adventure.

He drew a deep breath. In body he was still in his employer’s office, but in spirit he was making his way through the streets of a little sun-baked town that lay in the shadow of towering mountains. And as he passed along the natives nudged one another, awed.

“There he goes,” they were saying. “See that man! Hard-Case Conway! They don’t come any tougher.”

IT was getting on for lunch-time when Berry, having completed the purchase of the theatre-tickets, sauntered from the emporium of the Messrs. Mellon and Pirbright into the rattle and glitter of Bond Street once more.

The day seemed now to have touched new heights of brilliance. There was sunshine above and sunshine in his heart. A magic ecstasy thrilled the air. He gazed upon Bond Street, fascinated.

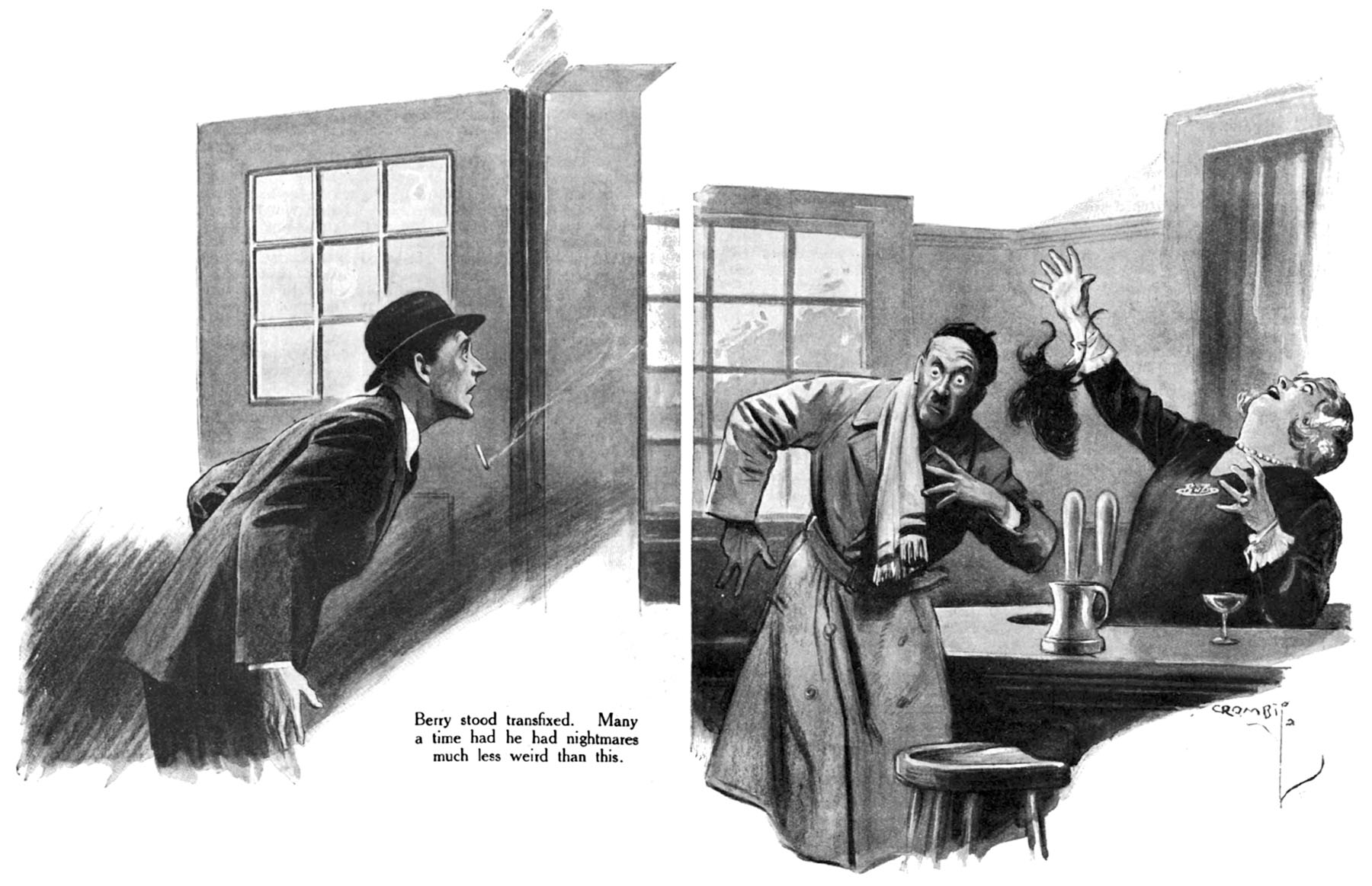

It was his practice, when walking in London, to look hopefully about him on the chance of exciting things happening. Nothing of the slightest interest had ever happened yet, and he had sometimes felt discouraged. But Bond Street restored his optimism. This, he felt, was a spot where anything might occur at any moment.