The Strand Magazine, June 1915

E

was black, but comely. Obviously in reduced circumstances, he had contrived,

nevertheless, to retain a certain smartness, a certain air—what the

French call the tournure. Nor had poverty killed in him the aristocrat’s

instinct of personal cleanliness; for, even as Elizabeth caught sight of

him, he began to wash himself.

E

was black, but comely. Obviously in reduced circumstances, he had contrived,

nevertheless, to retain a certain smartness, a certain air—what the

French call the tournure. Nor had poverty killed in him the aristocrat’s

instinct of personal cleanliness; for, even as Elizabeth caught sight of

him, he began to wash himself.

At the sound of her step he looked up. He did not move, but there was suspicion in his attitude. The muscles of his back contracted; his eyes glowed like yellow lamps against black velvet; his tail switched a little, warningly.

Elizabeth looked at him. He looked at Elizabeth.

“Why, see who’s here!” said Elizabeth.

There was a pause, while he summed her up. Then he stalked towards her and, suddenly lowering his head, drove it vigorously against her dress. He permitted her to pick him up and carry him into the hall-way, where Francis, the lift-man, stood waiting in his lethargic way to take her up to her apartment.

“Francis,” said Elizabeth, “does this cat belong to anyone here?”

“No, miss. That cat’s a stray, that cat is. I been trying to lo-cate that cat’s owner for days.”

Francis spent his time trying to lo-cate things. It was the one recreation of his eventless life. Sometimes it was a noise, sometimes a lost letter, sometimes a piece of ice which had gone astray in the dumbwaiter; whatever it was, Francis tried to lo-cate it.

“Has he been round here long, then?”

“Has he been round here long, then?”

“I seen him snooping about considerable time.”

“Then he must have been trying to lo-cate me,” said Elizabeth. “I shall keep him.”

“Black cats bring luck,” said Francis, sententiously.

“Well, that will suit me all right,” said Elizabeth. “I don’t object to luck.”

In the apartment, the door closed, she watched her new friend with some anxiety. You could never tell with cats; they changed their minds so quickly. His demeanour in the lift had been admirable—reserved, yet friendly. But she would not have been surprised, though it would have pained her, if he had now tried to escape through the ceiling, or had fled beneath the table and eyed her with the manner of one who knows that he has fallen among murderers, but is prepared to sell his life dearly.

The cat did none of these things. After padding silently about the room for a while, he raised his head and uttered a crooning cry.

“That’s right,” said Elizabeth, cordially. “If you don’t see what you want, ask for it. The place is yours.”

She went to the ice-box and produced milk and sardines. There was nothing finicky or affected about her guest. He was a good trencher-man; he did not care who knew it. He concentrated himself on the restoration of his tissues with the purposeful air of one whose last meal is a dim memory. Elizabeth, brooding over him like a Providence, wrinkled her forehead in thought.

“Joseph,” she said at length, brightening. “That’s your name. Joseph. And oh, Joseph, my dear, you wouldn’t believe how lonesome I was till you came along. I hadn’t a soul to talk to except my cook. And she talks a sort of Norwegian English which you simply can’t follow. But now I’ve got you it’s all right. Yes, finish those sardines; they’re all for you.”

Joseph settled down. He settled down amazingly. By the end of

the second day he was conveying the impression, as cats have the knack

of doing, that he was the real owner of the apartment, and that it was

due to his good nature that Elizabeth was allowed the run of the place.

Like all cats, he was an autocrat. He waited a day to ascertain which was

Elizabeth’s favourite chair, then appropriated it for his own. If

Elizabeth closed a door while he was in a room, he wanted it opened so

that he might go out; if she closed it while he was outside, he wanted

it opened so that he might go in; if she left it open, he fussed about

the draught. But the best of us have our little faults, and Elizabeth adored

him in spite of his.

Joseph settled down. He settled down amazingly. By the end of

the second day he was conveying the impression, as cats have the knack

of doing, that he was the real owner of the apartment, and that it was

due to his good nature that Elizabeth was allowed the run of the place.

Like all cats, he was an autocrat. He waited a day to ascertain which was

Elizabeth’s favourite chair, then appropriated it for his own. If

Elizabeth closed a door while he was in a room, he wanted it opened so

that he might go out; if she closed it while he was outside, he wanted

it opened so that he might go in; if she left it open, he fussed about

the draught. But the best of us have our little faults, and Elizabeth adored

him in spite of his.

It was astonishing what a difference he made in her life. She was a friendly soul, and, until Joseph’s arrival, all the company she had had consisted of Francis, the lift-man, Frida, the Norwegian cook, and the footsteps of the man in the apartment across the way. Moreover, the apartment-house was an old one, and it creaked at night. There was a loose board under the carpet near the box-room, which was half-way house on the road to bed, and when you stepped on it there was a sound like burglars in the darkness behind you. Funny scratching-noises made you jump and hold your breath. Altogether, a ramshackle, eerie sort of an apartment, disturbing to live alone in.

Joseph changed all this. With Joseph around, a loose board became a loose board—nothing more—and a scratching-noise just a harmless scratching-noise. Elizabeth could hardly understand how she had got along without him.

And then one afternoon he disappeared.

The apartment was so large that the full realization of the

tragedy did not come home to Elizabeth immediately. When she opened the

door of the sitting-room and found it empty she said, “He is in the

kitchen.” Having explored the kitchen, she said, “He must be

in the bath-room”—for one of the many traits which marked Joseph

off from the ordinary cat was his curious fondness for water as a beverage.

He was often to be found in the bath-tub, endeavouring to extract moisture

from its arid porcelain. But, no—in the bathroom, too, she drew blank;

and in the box-room, the spare bedroom, the dressing-room and her own bedroom.

He had gone.

The apartment was so large that the full realization of the

tragedy did not come home to Elizabeth immediately. When she opened the

door of the sitting-room and found it empty she said, “He is in the

kitchen.” Having explored the kitchen, she said, “He must be

in the bath-room”—for one of the many traits which marked Joseph

off from the ordinary cat was his curious fondness for water as a beverage.

He was often to be found in the bath-tub, endeavouring to extract moisture

from its arid porcelain. But, no—in the bathroom, too, she drew blank;

and in the box-room, the spare bedroom, the dressing-room and her own bedroom.

He had gone.

Of the possibility—nay, the probability—of this frightful occurrence, she remembered, Frida had warned her on the first afternoon. “You batter keeping good eye on him, or I bat you he rooning away. Yust so soon as ever he finding nicer place, he beating it.” Those were Frida’s words—ridiculed at the time, but now proved to have been inspired.

The logical inference that, as he was not in the apartment, he must be outside it, sent Elizabeth to the window, with the intention of submitting the street to one last inspection. She was not hopeful, for she had just come from the street, and there had been no signs of him then.

Outside the window was a broad ledge, running the width of the building. It terminated on the left in a shallow balcony belonging to the apartment whose front door faced hers—the apartment of the young man whose footsteps she sometimes heard. She knew he was a young man, because Francis had told her so. His name, James Renshaw Boyd, she had learned from the same source.

On this shallow balcony, the property of James Renshaw Boyd, licking his fur with the tip of a crimson tongue and generally behaving as if he were in his own back-yard, sat Joseph.

“JOo-seph!” cried Elizabeth, surprise, joy, and reproach combining to give her voice an almost melodramatic quiver.

He looked at her—coldly. Worse, he looked at her as if she had been an utter stranger. No light of pleased recognition gleamed in his yellow eyes. For a space he surveyed her, as if musing on the forwardness of strange females who addressed him by his first name; then, turning, he walked into the next apartment.

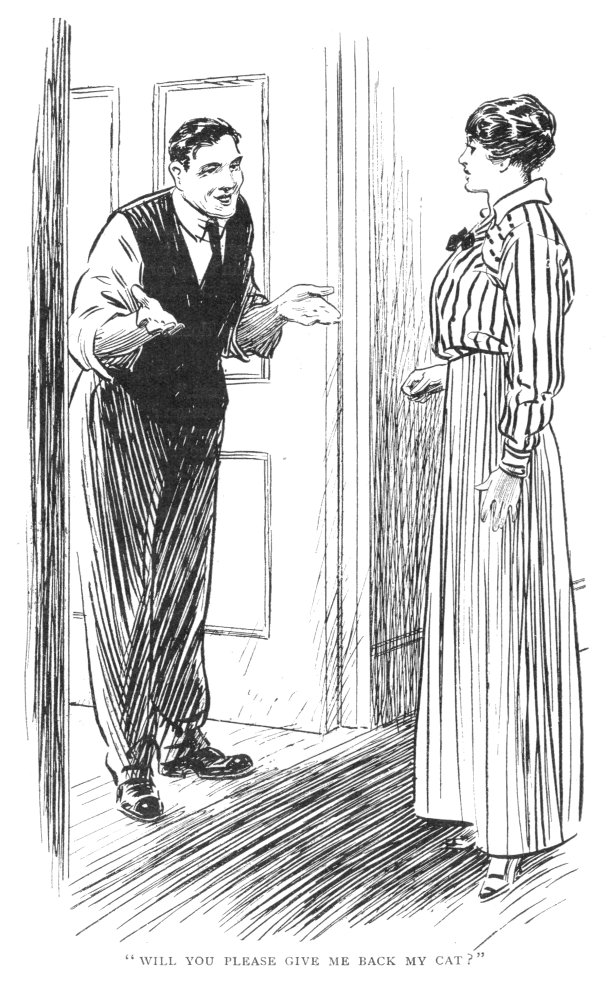

Elizabeth was a girl of spirit. Joseph might look at her as if she were a saucerful of tainted milk, but he was her cat, and she meant to get him back. She went out and rang the bell of Mr. James Renshaw Boyd’s apartment.

The door was opened by a shirt-sleeved young man. He was by

no means an unsightly young man. Indeed, of his type—the rough-haired,

clean-shaven, square-jawed type—he was a distinctly good-looking

young man. Even though she was regarding him at the moment purely in the

light of a machine for returning strayed cats, Elizabeth noticed that.

The door was opened by a shirt-sleeved young man. He was by

no means an unsightly young man. Indeed, of his type—the rough-haired,

clean-shaven, square-jawed type—he was a distinctly good-looking

young man. Even though she was regarding him at the moment purely in the

light of a machine for returning strayed cats, Elizabeth noticed that.

She smiled upon him. It was not the fault of this nice-looking young man that his sitting-room window was open, or that Joseph was an ungrateful little beast who should have no fish that night.

“Would you mind letting me have my cat, please?” she said, pleasantly. “He has gone into your sitting-room through the window.”

He looked faintly surprised.

“Your cat?”

“My black cat, Joseph. He is in your sitting-room.”

“I’m afraid you have come to the wrong place. I’ve just left my sitting-room, and the only cat there is my black cat, Reginald.”

“But I saw Joseph go in only a minute ago.”

“That was Reginald.”

For the first time, as one who, examining a fair shrub, suddenly finds that it is poison-ivy, Elizabeth realized the truth. This was no innocent, well-meaning young man who stood before her, but the blackest criminal known to criminologists—a stealer of other people’s cats. Her manner shot down to zero, and below it, in the space of a quarter of a second.

“May I ask how long you have had Reginald?”

“Since four o’clock this afternoon.”

“Did he come in through the window?”

“Why, yes. Now you mention it, he did.”

“I must ask you to be good enough to give me back my cat at once,” said Elizabeth, icily.

He looked at her with something almost of appeal in his gaze.

He looked at her with something almost of appeal in his gaze.

“Assuming,” he said, “purely for the purposes of academic argument, that my Reginald is your Joseph, couldn’t we come to an agreement of some sort? Let me buy you another cat—a dozen cats.”

“I don’t want a dozen cats. I want Joseph.”

“But why?”

“Because he is my cat.”

“There is no other reason? You are not superstitious, for instance? You have no beliefs about black for luck, and so on?”

Elizabeth was superstitious—profoundly so; but she was too vexed to admit it.

“Of course I don’t believe in anything so silly.”

“That settles it,” said the young man, with sudden determination. “I’m sorry, but I cannot let Reginald go.”

Elizabeth’s cheeks were pink, and her voice shook with indignation.

“Do you intend to steal my cat?”

He made a gesture of remonstrance.

“Those are harsh words. Any lawyer will tell you that there are special statutes respecting cats. To retain a stray cat is not a tort or a misdemeanour. In the celebrated test-case of ‘Wiggins versus Bluebody’ it was established——”

“Will you please give me back my cat?”

“Your cat? Now, in what sense your cat? Did you buy him? No. Nobody buys a cat. You found him straying, and gathered him in. In the circumstances, I am extremely sorry, but——”

The remainder of the remark was lost in the slam of Elizabeth’s door. The young man stood for a moment looking after her, then sighed, and closed his own door. The negotiations were ended: war had begun.

With her chin in her hands, Elizabeth sat in her bereaved sitting-room

and boiled. For a time wrath at this pleasant-faced but black-hearted buccaneer

kept the sense of bereavement in check. But soon the realization of her

loss struck home. Her set mouth quivered and her eyes filled with tears.

Joseph was all she had, her only friend. She would have died rather than

use this plea in an argument in which all moral right was on her side,

but it was the kernel of the matter. The loss of Joseph meant the return

of that horrible desolation of loneliness. Once more she was faced by solitude

in the day and burglar-sounds and scratching-noises in the night.

With her chin in her hands, Elizabeth sat in her bereaved sitting-room

and boiled. For a time wrath at this pleasant-faced but black-hearted buccaneer

kept the sense of bereavement in check. But soon the realization of her

loss struck home. Her set mouth quivered and her eyes filled with tears.

Joseph was all she had, her only friend. She would have died rather than

use this plea in an argument in which all moral right was on her side,

but it was the kernel of the matter. The loss of Joseph meant the return

of that horrible desolation of loneliness. Once more she was faced by solitude

in the day and burglar-sounds and scratching-noises in the night.

She buried her face in the sofa-cushion and cried it damp.

Tears brought energy and resource. She went to the ice-box, and took therefrom a fine fish. Frida, she knew, was reserving this for the keystone or coping-stone of her approaching dinner, but she required it for a more important end. She understood Joseph’s character sufficiently clearly now to feel convinced that this fine fish, placed on the ledge outside her window, would infallibly draw him back to—— But it did not. There it lay, glistening but ignored. And the wind in the right direction! She could not understand it. Had Joseph suddenly turned ascetic?

She leaned out of the window, to supplement her offering with seductive cat-noises—little whistles and chirrups which alone should have been enough to draw him; and, as she did so, she perceived that the other window was shut. Somewhere behind it, it might be, Joseph chafed for freedom like a prisoned soul; but nor fish nor chirrup could draw him through a stout pane of glass.

Elizabeth withdrew in disorder. She had been out-generalled.

We pay, in these modern days, for the resources of civilization

with the small discomforts which spring from them. The elevator is a useful

and convenient thing, saving time and labour; but it has its drawbacks.

It is not pleasant, for instance, to be cooped up in one with a deadly

foe.

We pay, in these modern days, for the resources of civilization

with the small discomforts which spring from them. The elevator is a useful

and convenient thing, saving time and labour; but it has its drawbacks.

It is not pleasant, for instance, to be cooped up in one with a deadly

foe.

Elizabeth had poise. She did not show her embarrassment when James Renshaw Boyd stepped into the lift just after she had entered it, but she certainly felt embarrassed; and all the way down she was conscious that she was looking like something stuffed. When Francis finally threw the door open, which he did in his usual horribly leisurely way, she was out and walking rapidly down the street before the young man could extricate himself.

But he, too, was evidently a rapid walker. She had only gone a few steps when she heard his voice at her side.

“Miss Herrold.”

Even in her indignation, Elizabeth was not insensible to the compliment implied in the fact that he had taken the trouble to find out her name.

“We seem to be going the same way. I wish you would let me walk with you. I want to explain.”

“Explain?”

“About Reg—about Joseph.”

Elizabeth said nothing, but she slackened her pace. One gets so lonely in New York, when one knows nobody and has lost one’s cat, that really to talk with an enemy is better than solitary silence.

“In the first place,” he went on, “I admit the cat is your cat, and that I have no right to it, and that I’m just a common sneak-thief, and that I behaved at our last meeting like a cad and a hound, and—and all the other things you’ve been calling me all this time. Does that pave the way for the Hague Convention at all?”

Elizabeth tried not to smile; and, vowing she would ne’er

smile, smiled. She could not help it. Nature had given her a warm heart

and a friendly disposition, and, being always honest with herself, she

admitted in the privacy of her own mind that this young man attracted her.

Had they met in happier circumstances she felt she might have liked him

very much indeed. Of course, things being as they were, friendship was

impossible. He had behaved abominably; he had done her a grievous wrong;

he had—however, she smiled.

Elizabeth tried not to smile; and, vowing she would ne’er

smile, smiled. She could not help it. Nature had given her a warm heart

and a friendly disposition, and, being always honest with herself, she

admitted in the privacy of her own mind that this young man attracted her.

Had they met in happier circumstances she felt she might have liked him

very much indeed. Of course, things being as they were, friendship was

impossible. He had behaved abominably; he had done her a grievous wrong;

he had—however, she smiled.

The young man brightened up as if he had received an unexpected legacy. His whole manner changed. He began to talk as if they were old friends.

“It’s this way. I’ll tell you the whole thing. It will probably seem idiotic to you. It is idiotic. But I can’t help it. I’m as superstitious as a coon. That’s my only excuse. I had just come back from the first rehearsal of my first play that afternoon, and, as I walked in at the door, this black cat walked in at the window. It seemed like something specially sent. I felt that to give it up would be equivalent to killing the play before it ever was produced. Of course you will think me crazy, but that’s how it was.”

A sensation almost of faintness accompanied the revulsion of feeling which swept through Elizabeth. How she had misjudged this nice young man! She had taken him for an ordinary, soulless purloiner of cats, and all the time he had been reluctantly compelled to the act by this deep—one might almost call it holy—motive.

She beamed upon him, and he blinked as if he had encountered an unexpected searchlight.

“Why, of course you couldn’t let him go! It would have meant awful bad luck.”

“But I—I thought you didn’t believe——”

“Of course, I mean from your point of view.”

“Oh, yes, of course.”

“In any case, it would be like Sir Philip Sidney and the wounded soldier—‘your need is greater than mine.’ Think of all the people who are dependent on your play being a success!”

The young man blinked again.

“This is more than I ever hoped for,” he said. “I had an idea that you might understand, but I never expected this—enthusiasm. It’s awfully good of you, but I still feel mean.”

“Oh, but you mustn’t. Joseph was nothing to me—at least, nothing much—that is to say, well, I suppose I was rather fond of him, but he was not—not——”

“Vital?”

“That’s just the word I wanted. He was just company, you know.”

“Haven’t you many friends?”

“I haven’t any friends.”

She spoke simply, without any effort at pathos, but the young

man stopped in his tracks, and gasped. “You haven’t any friends!

Are you all alone in New York?”

She spoke simply, without any effort at pathos, but the young

man stopped in his tracks, and gasped. “You haven’t any friends!

Are you all alone in New York?”

Elizabeth smiled. It was curiously pleasant to find that her plight produced so much consternation in him.

“Well, no; as a matter of fact I haven’t. But it isn’t quite such a desperate situation as it sounds. It’s only temporary. I came all the way from Canada to keep house for my brother; and I’d only just got here when he had to leave. He’s one of the secretaries of a very restless old millionaire, you see; and the day I arrived he got one of his restless fits, and decided to go off in his yacht to the Azores; and of course all the poor secretaries had to go too. Well, it hardly seemed worth while going back to Canada again, as my brother might be back at any moment, so I just stayed on. It was rather fun at first, but I must say it got lonesome after a while. New York’s such a deceptive city. It seemed so pleased to see me at first, but really all the time it didn’t care a bit about me; and I soon found it out.”

“Good Lord!”

“For a time I was perfectly happy, just feeling that I was really walking down Broadway and Fifth Avenue at last, as I had dreamed of doing ever since I was quite small. Then I began to get bored. I tried not to be. There seemed something almost wicked to me in the idea of feeling bored in New York. But I couldn’t help it, and in the end I became so lonely I could have cried.”

“And then Joseph came along?”

“Well, yes. Then, as you say, Joseph came along.”

A look of holy resolution came into his face—such a look as some saint might have worn when renouncing worldly wealth and happiness.

“You must take him back.”

“I couldn’t think of it.”

“Of course you must take him back at once. I never dreamed of anything like this.”

“I really couldn’t.”

“But indeed you must.”

“I won’t.”

“Good gracious, how do you suppose I should feel, knowing that you were all alone and that I had sneaked your—your ewe-lamb, as it were?”

“And how do you suppose I should feel if your play failed simply for lack of a black cat?”

“Oh, that’s all absurd.”

“Absurd? You know perfectly well that it would be courting disaster for you to let Joseph go—I mean Reginald.”

“Then there’s only one thing to be done. Whenever you feel lonesome you must simply step across, ring my bell, and come and chat with Reginald—I should have said Joseph—in my apartment.”

Elizabeth’s was a country-trained mind, and she still retained a fairly extensive respect for the conventions; but the offer was too tempting to refuse.

“I should love it,” she said.

The gods are just. For every ill which they inflict they also

supply a compensation. It seems good to them that individuals in big cities

shall be lonely, but they have so arranged that, if one of these individuals

does at long last contrive to seek out and form a friendship with another,

that friendship shall grow more swiftly than the tepid acquaintances of

those on whom the icy touch of loneliness has never fallen. Within a week

Elizabeth was feeling that she had known this James Renshaw Boyd all her

life. Their minds seemed to run together like a well-matched pair of horses.

The gods are just. For every ill which they inflict they also

supply a compensation. It seems good to them that individuals in big cities

shall be lonely, but they have so arranged that, if one of these individuals

does at long last contrive to seek out and form a friendship with another,

that friendship shall grow more swiftly than the tepid acquaintances of

those on whom the icy touch of loneliness has never fallen. Within a week

Elizabeth was feeling that she had known this James Renshaw Boyd all her

life. Their minds seemed to run together like a well-matched pair of horses.

His modesty charmed her.

“Is this play of yours the very first you have ever written?” she asked him. “I think it’s wonderful to have had your first play accepted.”

“M-yes,“ he said, doubtfully, and changed the subject, as if it hurt him to contemplate his remarkableness.

On every other aspect of the forthcoming drama, however, he was always ready to talk. Not unnaturally, it occupied most of his thoughts. He told Elizabeth the plot of it, and, if he had not kept forgetting important episodes and having to leap back to them across a gulf of one or two acts, and if he had referred to his characters by name instead of by such descriptions as “the fellow who’s in love with the girl—not what’s-his-name, but the other chap,” she would no doubt have got that mental half-nelson on it which is such a help towards the proper understanding of a four-act comedy. As it was, his précis left her a little vague; but she said it was perfectly splendid, and he said, Did she really think so? and she said, Oh, yes, she really did, and they were both happy.

The unconventionality of their friendship soon ceased to trouble her. Their relations, she told herself, were so splendidly unsentimental. If James Renshaw Boyd had been her brother Jack—now in mid-Atlantic, painfully trying to take down shorthand notes from dictation without being sea-sick—she could not have felt more perfectly safe.

And that was why, when the thing happened, it so shocked and frightened her, and set the country-bred conscience, which had gone to sleep against its better judgment, screaming so loudly and unanswerably its accusing “I told you so!”

It had been one of their quiet evenings. Of late they had fallen into the habit of sitting for long periods together without speaking—a fact which should have warned her of danger, but did not. To-night neither had been inclined for conversation, for it was the night of all nights, the night when the play was to have its Broadway production. James had come in, outwardly calm, inwardly an inferno of leaping nerves, and she had fallen in with his mood and considerately abstained from jarring speech. She sat in her chair, nursing Joseph; he in his, staring glassily into space. And so, in a dim light, time had flowed by.

Just how it happened she never knew. One moment, peace; the next, chaos. One moment, stillness and quiet; the next, Joseph hurtling through the air, all claws and expletives, and herself caught in a clasp which shook the breath from her.

Nothing, apparently, had led up to this; it had just fallen on her without reason; and such was the shock of surprise that for a moment she was not conscious of indignation—or, indeed, of any sensation except the purely physical one of semi-strangulation. Then, like a wave, realization poured in on her, and she began to struggle.

Flushed, and more bitterly angry than she could ever have imagined herself capable of being, she tore herself from him. At the back of her anger, feeding it, was the humiliating thought that it was all her own fault, that by her presence there she had invited this.

She groped her way to the door. Something was writhing and struggling

inside her, blinding her eyes and robbing her of speech. She was only conscious

of a desire to be alone, to be back and safe in her own home. She was aware

that he was speaking, but the words did not reach her. She found the door

and pulled it open. She felt a hand on her arm, but she shook it off. And

then she was back behind her own door, alone and at liberty to contemplate

at leisure the ruins of that little temple of friendship which she had

built up so carefully, and in which she had been so happy.

She groped her way to the door. Something was writhing and struggling

inside her, blinding her eyes and robbing her of speech. She was only conscious

of a desire to be alone, to be back and safe in her own home. She was aware

that he was speaking, but the words did not reach her. She found the door

and pulled it open. She felt a hand on her arm, but she shook it off. And

then she was back behind her own door, alone and at liberty to contemplate

at leisure the ruins of that little temple of friendship which she had

built up so carefully, and in which she had been so happy.

The broad fact that she would never forgive him was for a while her only coherent thought. To this succeeded the determination that she would never forgive herself. And, having thus placed beyond the pale the only two friends she had in New York, she was free to devote herself without hindrance to the task of feeling thoroughly lonely and wretched.

The shadows deepened. Across the street a sort of bubbling explosion, followed by a jerky glare that shot athwart the room, announced the lighting of the big arc-lamp on the opposite sidewalk. She resented it, being in the mood to prefer undiluted gloom; but she had not the energy to pull down the shade and shut it out. She sat where she was, thinking thoughts that hurt.

It was quite dark outside when she heard the door of the apartment opposite open and shut, and then a single ring at her own bell. She did not answer it, and it was not repeated. Her straining ears caught the faint rustle of paper, and then another ring and the clang of the ascending lift.

She waited until it had begun to descend, then went to the door. Underneath it, a scrap of paper jutted into the apartment.

She switched on the light and read it:—

“I’m sorry. Won’t you forgive me? I am just off to the theatre. Won’t you wish me luck? I feel sure it’s going to be a hit. Joseph is purring like a dynamo.—J. R. B.”

She ran to the window. All her resentment had gone. She loved him, and she knew now that she had always loved him. The one thing she desired at that moment was to catch a glimpse of him before he turned the corner.

He was out of sight, but he had left her something to keep him in her mind. As she leaned from the window her eye was caught by a movement to the left of her. The dim shape of Joseph moved restlessly on the little balcony.

“Oh, Joseph,” she whispered, “bring him luck! Bring him luck!”

Joseph was in social mood. Insinuating himself through the ironwork of the balcony, he began to stalk condescendingly towards her along the ledge, as one assured of a welcome and possibly of one of those light snacks which he so esteemed.

He was amazed to find the air suddenly full of abuse and hissings.

“Get back!” cried Elizabeth, appalled. “You little idiot, if you try to get out of that apartment before eleven o’clock I’ll kill you! Get back where you belong, and be a mascot.”

Joseph retreated indignantly, and Elizabeth sat down to her vigil.

The sensible thing is generally the last that occurs to anyone

as a reasonable step to take in a crisis; and Elizabeth did not adopt the

obvious course of going to the theatre to see for herself the reception

of the play. She faced the idea of doing so, but dismissed it. Stage fright

in its acutest form had gripped her, and the notion of paying for a seat

at the box-office and sitting in an orchestra-chair while New York coldly

formed its judgment was not to be entertained. Her plan was to wait till

James Boyd returned, and to receive the verdict from him.

The sensible thing is generally the last that occurs to anyone

as a reasonable step to take in a crisis; and Elizabeth did not adopt the

obvious course of going to the theatre to see for herself the reception

of the play. She faced the idea of doing so, but dismissed it. Stage fright

in its acutest form had gripped her, and the notion of paying for a seat

at the box-office and sitting in an orchestra-chair while New York coldly

formed its judgment was not to be entertained. Her plan was to wait till

James Boyd returned, and to receive the verdict from him.

The scheme miscarried. She had set one o’clock as the earliest hour at which she might reasonably expect him back, for on an occasion like this supper after the theatre would be almost inevitable. One o’clock came, and he was still absent. Two o’clock came; he had not returned. And somewhere between two and three, tired out, Elizabeth fell peacefully asleep on the sofa.

It was broad daylight when she awoke. Her watch had stopped, and she could not even guess at the time. At a venture she opened her front door and looked out to see if it was late enough for Francis to have laid the morning paper on her mat.

It was there—white and inviting; and somewhere in its folded interior must be the opinion of one in authority on last night’s play.

Dramatic criticisms have this peculiarity—that, if you are looking for them, they burrow and hide like rabbits. They dodge behind murders; they duck behind baseball reports; they lie up snugly behind Beatrice Mae Someone-or-other’s Advice to the Lovelorn. It was a full minute before Elizabeth found what she sought; and the first words of it smote her like a blow.

In that vein of delightful facetiousness which so endears him to all followers and perpetrators of the drama, the One In Authority rent and tore James Boyd’s play. He knocked James Boyd’s play down, and kicked it; he jumped on it with large feet; he poured cold water on it, and chopped it into little bits. He merrily disembowelled James Boyd’s play.

It took Elizabeth one minute to realize that the One In Authority was a dangerous lunatic who should not be permitted at large, another to run downstairs and out to the news-stand on the corner of the street. Here, with a lavishness which charmed and exhilarated the proprietor, she bought all the other papers which he could supply.

Moments of tragedy are best described briefly. Each of the papers noticed the play and each of them damned it with uncompromising heartiness. The criticisms varied in tone; one cursed with relish and gusto, another with a certain pity, a third with a kind of wounded superiority, as if compelled against his will to speak of something unspeakable; but the meaning of all was the same. James Boyd’s play was a hideous failure.

Back to the apartment-house sped Elizabeth, leaving the organs of a free people to be gathered up, smoothed, and replaced on the stand by a now more than ever charmed proprietor. Up the stairs she ran, and, arriving breathlessly at James Boyd’s door, rang the bell.

Heavy footsteps came down the passage—crushed, disheartened footsteps—footsteps that sent a chill to Elizabeth’s heart. The door opened. James Renshaw Boyd stood before her, heavy-eyed and haggard. In his eyes was despair, and on his chin the blue growth of beard of the man from whom Fate with its mailed fist has smitten the energy to perform his morning shave.

Neither spoke. He led the way into the sitting-room.

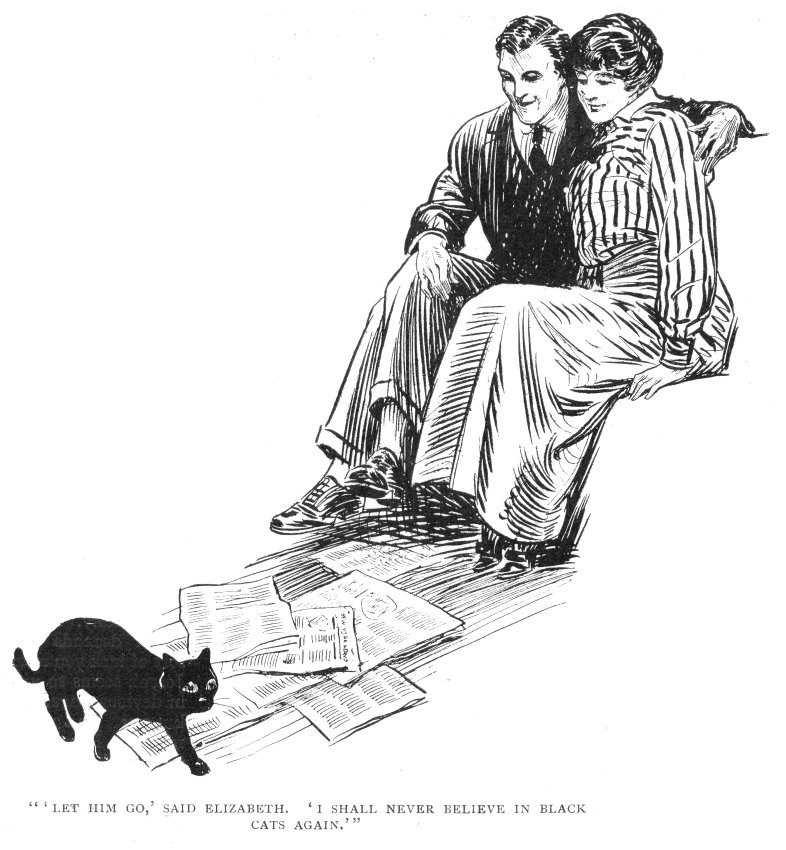

There, littering the floor, were all the morning papers, and at the sight of them Elizabeth broke down.

“Oh, Jimmy, darling!” she cried; and the next moment she was in his arms, and for a space time stood still.

How long afterwards it was, she never knew; but eventually James Boyd spoke.

“If you’ll marry me,” he said, hoarsely, “I don’t care a hang.”

“Jimmy, darling,” said Elizabeth, “of course I will.”

It was as they sat side by side, contemplating in silence a world not wholly dark, that a black streak shot silently from beneath a bookshelf and passed from the room. Joseph, as has been said, was an autocrat. He liked his breakfast punctually at the selected hour, and, if he did not get it, he showed his resentment by flight.

“Let him go, the fraud!” said Elizabeth, bitterly. “I shall never believe in black cats again.”

But James Boyd, encircling her fondly, was not of this opinion.

“Joseph has brought me all the luck I need.”

“But you told me ever so many times that the play meant everything to you.”

“It did then.”

Elizabeth hesitated.

“Jimmy, dear, it’s all right, you know. I mean, if it was the money you were thinking of. I’ve got a little income, enough for us to live on till you make good. I know you will make a fortune out of your next play.”

“I wouldn’t touch a cent of it.”

“But, Jimmy, if we can’t get married I shall just die.”

“Oh, we’ll get married all right. Don’t you worry about that. I wasn’t thinking of the money end of it when I said that the play meant everything to me. Money is my middle name. At least, it’s my father’s, and he’s such a corker that it comes to the same thing. Honey, in your more material moments have you ever toyed with a Boyd’s Premier Breakfast Sausage, or kept the wolf from the door with a slice off a Boyd’s Excelsior Home-Cured Ham? Dad makes them, and the tragedy of my young life up to the present has been that he was dead set on my jumping in and helping him at it. This was the position. I had a notion—a fool notion, as it turns out—that I could make good in the literary line. I’ve scribbled in a sort of way ever since I went to college. When the time came for me to join the firm I put it to dad straight. I said, ‘Give me a chance to see if the divine fire is really there, or if somebody has merely turned in an alarm as a practical joke.’ And we made a bargain. I’d written this play, and what we fixed up was that dad should put up the money to give it a Broadway production. If it succeeded, all right; I’m the boy genius, and may go ahead. If it is a fizzle, off goes my coat and I abandon pipe-dreams of literary triumph and start in as the guy in David Boyd and Co., pork packers, Chicago, Ill.

“Well, events have proved that I am the guy, and I’m going to keep my part of the bargain just as squarely as dad kept his. I know quite well that if I refused to play fair, and chose to stick on here in New York and try again, dad would go on staking me. That’s the sort of man he is. But I wouldn’t do it for a million Broadway successes. I’ve had my chance, and I’ve foozled; and now I’m going back to make him feel good by being a real live member of the firm. And the queer thing about it is that last night I loathed the idea, and this morning, now that I’ve got you, I almost kind of look forward to it.”

“Jimmy!”

He gave a little shiver.

“And yet—I don’t know! There’s something rather horrible in living in luxury on murdered pigs.”

“Well, try not to think of it, darling.”

“All right,” said James, dutifully.

There came a sudden shout from the floor above, and on the heels of it a shock-haired youth in pyjamas burst into the apartment, yelling for Jimmy. At the sight of Elizabeth he halted, pinkly embarrassed.

“Now what?” said Jimmy. “By the way, Miss Herrold, my fiancée; Mr. Briggs—Paul Axworthy Briggs, the Boy Novelist. What’s eating you, Paul?”

“Jimmy,” cried the Boy Novelist, “what do

you think has happened? A black cat has just come into my apartment. I

heard him mewing outside the door, and opened it, and he streaked in. And

I started my new novel last night! Say, you do believe this thing

of black cats bringing luck, don’t you?”

“Jimmy,” cried the Boy Novelist, “what do

you think has happened? A black cat has just come into my apartment. I

heard him mewing outside the door, and opened it, and he streaked in. And

I started my new novel last night! Say, you do believe this thing

of black cats bringing luck, don’t you?”

“Luck! My lad, grapple that cat to your soul with hoops of steel. He’s the greatest little luck-bringer in New York. He was boarding with me till this morning.”

“Then—by Jove! I nearly forgot to ask—your play was a hit? I haven’t seen the papers yet.”

“Well, when you see them, don’t read the notices. It was the worst frost Broadway has seen since Columbus’s time.”

“But—I don’t understand.”

“Don’t worry. You don’t have to. Go back and fill that cat with fish, or she’ll be leaving you. I suppose you left the door open?”

“By Jove!” said the Boy Novelist, paling, and dashed for the door.

“Do you think Joseph will bring him luck?” said Elizabeth thoughtfully.

“It depends what sort of luck you mean. Joseph seems to work in devious ways. If I know Joseph’s methods, Briggs’s new novel will be rejected by every publisher in the city; and then, when he is sitting in his apartment, wondering which of his razors to end himself with, there will be a ring at the bell, and in will come the most beautiful girl in the world, and then—well, then, take it from me, he will be all right.”

“He won’t mind about the novel?”

“Not in the least.”

“Not even if it means that he will have to go away and kill pigs and things?”

“Not if he has to slay them with his own hands.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums