The Strand Magazine, May 1924

THE summer afternoon was warm and heavy. Butterflies loafed languidly in the sunshine, birds panted in the shady recesses of the trees. With the exception of an occasional perspiring bee that buzzed past intent on some mysterious duty, the only creatures exhibiting any activity were the members of a four-ball foursome working its way up the hill from the eighth tee. The Oldest Member of the club, snug in his favourite chair on the terrace overlooking the ninth green, had long since succumbed to the drowsy influence of the weather. His eyes were closed, his chin sunk upon his breast. The pipe which he had been smoking lay beside him on the turf, and ever and anon there proceeded from him a muffled snore. Two young men, wandering towards the tennis-courts, stepped lightly as they passed him. This was partly because they thought the nap would be good for their venerable friend; partly because it was his habit, when awake, to buttonhole the nearest person and relate to him one of the innumerable reminiscences of his golfing past. The Oldest Member, though he had not played since the days of the gutty ball, still kept in touch with the game through the medium of speech.

Suddenly the stillness was broken. There was a sharp, cracking sound as of splitting wood. It rang out like the report of a rifle, and the Oldest Member sat up, blinking. As soon as his eyes had become accustomed to the glare, he perceived that the foursome had holed out on the ninth and was disintegrating. Two of the players were moving with quick, purposeful steps in the direction of the side door which gave entrance to the bar; a third was making for the road that led to the village, bearing himself as one in profound dejection; the fourth came on to the terrace.

“Finished?” said the Oldest Member, accosting this individual.

The other stopped, wiping a heated brow. He lowered himself into the adjoining chair and stretched his legs out.

“Yes. We started at the tenth. Golly, I’m tired. No joke playing in this weather.”

“How did you come out?”

“We won on the last green. Jimmy Fothergill and I were playing the vicar and Rupert Blake.”

“What was that sharp, cracking sound I heard?” asked the Oldest Member.

His companion laughed, the care-free laugh of the man to whom the gods of golf have granted a happy ending.

“That was the vicar smashing his putter. He had a two-foot putt to halve the hole and match, and he missed it. Poor old chap, he had rotten luck all the way round, and it didn’t seem to make it any better for him that he wasn’t able to relieve his feelings in the ordinary way. Golly, I’m tired,” he said once more, and, wriggling himself into a more comfortable position, he closed his eyes.

“I suspected some such thing,” said the Oldest Member, “from the look of his back as he was leaving the green. His walk was the walk of an overwrought soul.”

His companion did not reply. He was breathing deeply and regularly.

“It is a moot question,” proceeded the Oldest Member, thoughtfully, “whether the clergy, considering their peculiar position, should not be more liberally handicapped at golf than the laymen with whom they compete. I have made a close study of the game since the days of the feather ball, and I am firmly convinced that to refrain entirely from oaths during a round is almost equivalent to giving away three bisques. There are certain occasions when an oath seems to be so imperatively demanded that the strain of keeping it in must inevitably affect the ganglions or nerve-centres in such a manner as to diminish the steadiness of the swing.”

The man beside him slipped lower down in his chair. His mouth had opened slightly.

“I am reminded in this connection,” said the Oldest Member, “of the story of young Chester Meredith, a friend of mine whom you have not, I think, met. He moved from this neighbourhood shortly before you came. There was a case where a man’s whole happiness was very nearly wrecked purely because he tried to curb his instincts and thwart nature in this very respect. Perhaps you would care to hear the story?”

A snore proceeded from the next chair.

“Very well, then,” said the Oldest Member, “I will relate it.”

CHESTER MEREDITH (said the Oldest Member) was one of the nicest young fellows of my acquaintance. We had been friends ever since he had come to live here as a small boy, and I had watched him with a fatherly eye through all the more important crises of a young man’s life. It was I who taught him to drive, and when he had all that trouble in his twenty-first year with shanking his short approaches, it was to me that he came for sympathy and advice. It was an odd coincidence, therefore, that I should have been present when he fell in love.

I was smoking my evening cigar out here and watching the last couples finishing their rounds, when Chester came out of the club-house and sat by me. I could see that the boy was perturbed about something, and wondered why, for I knew that he had won his match.

“What,” I inquired, “is on your mind?”

“Oh, nothing,” said Chester. “I was only thinking that there are some human misfits who ought not to be allowed on any decent links.”

“You mean——?”

“The Wrecking Crew,” said Chester, bitterly. “They held us up all the way round, confound them. Wouldn’t let us through. What can you do with people who don’t know enough of the etiquette of the game to understand that a single has right of way over a four-ball foursome? We had to loaf about for hours on end while they scratched at the turf like a lot of crimson hens. Eventually all four of them lost their balls simultaneously at the eleventh and we managed to get by. I hope they choke.”

I was not altogether surprised at his warmth. This Wrecking Crew consisted of four retired business men who had taken up the noble game late in life because their doctors had ordered them air and exercise. Every club, I suppose, has a cross of this kind to bear, and it was not often that our members rebelled; but there was undoubtedly something particularly irritating in the methods of the Wrecking Crew. They tried so hard that it seemed almost inconceivable that they should be so slow.

“They are all respectable men,” I said, “and were, I believe, highly thought of in their respective businesses. But on the links I admit that they are a trial.”

“They are the direct lineal descendants of the Gadarene swine,” said Chester, firmly. “Every time they come out I expect to see them rush down the hill from the first tee and hurl themselves into the lake at the second. Of all the——”

“Hush!” I said.

Out of the corner of my eye I had seen a girl approaching, and I was afraid lest Chester in his annoyance might use strong language. For he was one of those golfers who are apt to express themselves in moments of emotion with a good deal of generous warmth.

“Eh?” said Chester.

I jerked my head, and he looked round. And, as he did so, there came into his face an expression which I had seen there only once before, on the occasion when he won the President’s Cup on the last green by holing a thirty-yard chip with his mashie. It was a look of ecstasy and awe. His mouth was open, his eyebrows raised, and he was breathing heavily through his nose.

“Golly!” I heard him mutter.

The girl passed by. I could not blame Chester for staring at her. She was a beautiful young thing, with a lissom figure and a perfect face. Her hair was a deep chestnut, her eyes blue, her nose small and laid back with about as much loft as a light iron. She disappeared, and Chester, after nearly dislocating his neck trying to see her round the corner of the club-house, emitted a deep, explosive sigh.

“Who is she?” he whispered.

I could tell him that. In one way and another I get to know most things around this locality.

“She is a Miss Blakeney. Felicia Blakeney. She has come to stay for a month with the Waterfields. I understand she was at school with Jane Waterfield. She is twenty-three, has a dog named Joseph, dances well, and dislikes parsnips. Her father is a distinguished writer on sociological subjects; her mother is Wilmot Royce, the well-known novelist, whose last work, ‘Sewers of the Soul,’ was, you may recall, jerked before a tribunal by the Purity League. She has a brother, Crispin Blakeney, an eminent young reviewer and essayist, who is now in India studying local conditions with a view to a series of lectures. She only arrived here yesterday, so this is all I have been able to find out about her as yet.”

Chester’s mouth was still open when I began speaking. By the time I had finished it was open still wider. The ecstatic look in his eyes had changed to one of dull despair.

“My God!” he muttered. “If her family is like that, what chance is there for a roughneck like me?”

“You admire her?”

“She is the alligator’s Adam’s apple,” said Chester, simply.

I patted his shoulder.

“Have courage, my boy,” I said. “Always remember that the love of a good man to whom the pro. can only give a couple of strokes in eighteen holes is not to be despised.”

“Yes, that’s all very well. But this girl is probably one solid mass of brain. She will look on me as an uneducated wart-hog.”

“Well, I will introduce you, and we will see. She looked a nice girl.”

“You’re a great describer, aren’t you?” said Chester. “A wonderful flow of language you’ve got, I don’t think! Nice girl! Why, she’s the only girl in the world. She’s a pearl among women. She’s the most marvellous, astounding, beautiful, heavenly thing that ever drew perfumed breath.” He paused, as if his train of thought had been interrupted by an idea. “Did you say that her brother’s name was Crispin?”

“I did. Why?”

Chester gave vent to a few manly oaths.

“Doesn’t that just show you how things go in this rotten world?”

“What do you mean?”

“I was at school with him.”

“Surely that should form a solid basis for friendship?”

“Should it? Should it, by gad? Well, let me tell you that I probably kicked that blighted worm Crispin Blakeney a matter of seven hundred and forty-six times in the few years I knew him. He was the world’s worst. He could have walked straight into the Wrecking Crew and no questions asked. Wouldn’t it jar you? I have the luck to know her brother, and it turns out that we couldn’t stand the sight of each other.”

“Well, there is no need to tell her that.”

“Do you mean——?” He gazed at me wildly. “Do you mean I might pretend we were pals?”

“Why not? Seeing that he is in India, he can hardly contradict you.”

“My gosh!” He mused for a moment. I could see that the idea was beginning to sink in. It was always thus with Chester. You had to give him time. “By Jove, it mightn’t be a bad scheme at that. I mean, it would start me off with a rush, like being one up on bogey in the first two. And there’s nothing like a good start. By gad, I’ll do it.”

“I should.”

“Reminiscences of the dear old days when we were lads together, and all that sort of thing.”

“Precisely.”

“It isn’t going to be easy, mind you,” said Chester, meditatively. “I’ll do it because I love her, but nothing else in this world would make me say a civil word about the blister. Well, then, that’s settled. Get on with the introduction stuff, will you? I’m in a hurry.”

ONE of the privileges of age is that it enables a man to thrust his society on a beautiful girl without causing her to draw herself up and say “Sir!” It was not difficult for me to make the acquaintance of Miss Blakeney, and, this done, my first act was to unleash Chester on her.

“Chester,” I said, summoning him as he loafed with an overdone carelessness on the horizon, one leg almost inextricably entwined about the other, “I want you to meet Miss Blakeney. Miss Blakeney, this is my young friend Chester Meredith. He was at school with your brother Crispin. You were great friends, were you not?”

“Bosom,” said Chester, after a pause.

“Oh, really?” said the girl. There was a pause. “He is in India now.”

“Yes,” said Chester.

There was another pause.

“Great chap,” said Chester, gruffly.

“Crispin is very popular,” said the girl, “with some people.”

“Always been my best pal,” said Chester.

“Yes?”

I was not altogether satisfied with the way matters were developing. The girl seemed cold and unfriendly, and I was afraid that this was due to Chester’s repellent manner. Shyness, especially when complicated by love at first sight, is apt to have strange effects on a man, and the way it had taken Chester was to make him abnormally stiff and dignified. One of the most charming things about him was his delightful boyish smile. Shyness had caused him to iron this out of his countenance till no trace of it remained. Not only did he not smile, he looked like a man who never had smiled and never would. His mouth was a thin, rigid line. His back was stiff with what appeared to be contemptuous aversion. He looked down his nose at Miss Blakeney as if she were less than the dust beneath his chariot-wheels.

I thought the best thing to do was to leave them alone together to get acquainted. Perhaps, I thought, it was my presence that was cramping Chester’s style. I excused myself and receded.

IT was some days before I saw Chester again. He came round to my cottage one night after dinner and sank into a chair, where he remained silent for several minutes.

“Well?” I said at last.

“Eh?” said Chester, starting violently.

“Have you been seeing anything of Miss Blakeney lately?”

“You bet I have.”

“And how do you feel about her on further acquaintance?”

“Eh?” said Chester, absently.

“Do you still love her?”

Chester came out of his trance.

“Love her?” he cried, his voice vibrating with emotion. “Of course I love her. Who wouldn’t love her? I’d be a silly chump not loving her. Do you know,” the boy went on, a look in his eyes like that of some young knight seeing the Holy Grail in a vision, “do you know, she is the only woman I ever met who didn’t overswing. Just a nice, crisp, snappy half-slosh, with a good full follow-through. And another thing. You’ll hardly believe me, but she waggled almost as little as George Duncan. You know how women waggle as a rule, fiddling about for a minute and a half like kittens playing with a ball of wool. Well, she just makes one firm pass with the club and then bing! There is none like her, none.”

“Then you have been playing golf with her?”

“Nearly every day.”

“How is your game?”

“Rather spotty. I seem to be mistiming them.”

I was concerned.

“I do hope, my dear boy,” I said, earnestly, “that you are taking care to control your feelings when out on the links with Miss Blakeney. You know what you are like. I trust you have not been using the sort of language you generally employ on occasions when you are not timing them right?”

“Me?” said Chester, horrified. “Who, me? You don’t imagine for a moment that I would dream of saying a thing that would bring a blush to her dear cheek, do you? Why, a bishop could have gone round with me and learned nothing new.”

I was relieved.

“How do you find you manage the dialogue these days?” I asked. “When I introduced you, you behaved—you will forgive an old friend for criticizing—you behaved a little like a stuffed frog with laryngitis. Have things got easier in that respect?”

“Oh, yes. I’m quite the prattler now. I talk about her brother mostly. I put in the greater part of my time boosting the tick. It seems to be coming easier. Will-power, I suppose. And then, of course, I talk a good deal about her mother’s novels.”

“Have you read them?”

“Every damned one of them—for her sake. And if there’s a greater proof of love than that, show me! My gosh, what muck that woman writes! That reminds me, I’ve got to send to the bookshop for her latest—out yesterday. It’s called ‘The Stench of Life.’ A sequel, I understand, to ‘Grey Mildew.’ ”

“Brave lad,” I said, pressing his hand. “Brave, devoted lad!”

“Oh, I’d do more than that for her.” He smoked for awhile in silence. “By the way, I’m going to propose to her to-morrow.”

“Already?”

“Can’t put it off a minute longer. It’s been as much as I could manage, bottling it up till now. Where do you think would be the best place? I mean, it’s not the sort of thing you can do while you’re walking down the street or having a cup of tea. I thought of asking her to have a round with me and taking a stab at it on the links.”

“You could not do better. The links—Nature’s cathedral.”

“Right-o, then! I’ll let you know how I come out.”

“I wish you luck, my boy,” I said.

AND what of Felicia, meanwhile? She was, alas, far from returning the devotion which scorched Chester’s vital organs. He seemed to her precisely the sort of man she most disliked. From childhood up Felicia Blakeney had lived in an atmosphere of highbrowism, and the type of husband she had always seen in her daydreams was the man who was simple and straightforward and earthy and did not know whether Artbashiekeff was a suburb of Moscow or a new kind of Russian drink. A man like Chester, who on his own statement would rather read one of her mother’s novels than eat, revolted her. And his warm affection for her brother Crispin set the seal on her distaste.

Felicia was a dutiful child, and she loved her parents. It took a bit of doing, but she did it. But at her brother Crispin she drew the line. He wouldn’t do, and his friends were worse than he was. They were high-voiced, supercilious, pince-nezed young men who talked patronizingly of Life and Art, and Chester’s unblushing confession that he was one of them had put him ten down and nine to play right away.

You may wonder why the boy’s undeniable skill on the links had no power to soften the girl. The unfortunate fact was that all the good effects of his prowess were neutralized by his behaviour while playing. All her life she had treated golf with a proper reverence and awe, and in Chester’s attitude towards the game she seemed to detect a horrible shallowness. The fact is, Chester, in his efforts to keep himself from using strong language, had found a sort of relief in a girlish giggle, and it made her shudder every time she heard it.

His deportment, therefore, in the space of time leading up to the proposal could not have been more injurious to his cause. They started out quite happily, Chester doing a nice two-hundred-yarder off the first tee, which for a moment awoke the girl’s respect. But at the fourth, after a lovely brassie-shot, he found his ball deeply embedded in the print of a woman’s high heel. It was just one of those rubs of the green which normally would have caused him to ease his bosom with a flood of sturdy protest, but now he was on his guard.

“Tee-hee!” simpered Chester, reaching for his niblick. “Too bad, too bad!” and the girl shuddered to the depths of her soul.

Having holed out, he proceeded to enliven the walk to the next tee with a few remarks on her mother’s literary style, and it was while they were walking after their drives that he proposed.

His proposal, considering the circumstances, could hardly have been less happily worded. Little knowing that he was rushing upon his doom, Chester stressed the Crispin note. He gave Felicia the impression that he was suggesting this marriage more for Crispin’s sake than anything else. He conveyed the idea that he thought how nice it would be for brother Crispin to have his old chum in the family. He drew a picture of their little home, with Crispin for ever popping in and out like a rabbit. It is not to be wondered at that, when at length he had finished and she had time to speak, the horrified girl turned him down with a thud.

It is at moments such as these that a man reaps the reward of a good upbringing. In similar circumstances those who have not had the benefit of a sound training in golf are too apt to go wrong. Goaded by the sudden anguish, they take to drink, plunge into dissipation, and write vers libre. Chester was mercifully saved from this. I saw him the day after he had been handed the mitten, and was struck by the look of grim determination in his face. Deeply wounded though he was, I could see that he was the master of his fate and the captain of his soul.

“I am sorry, my boy,” I said, sympathetically, when he had told me the painful news.

“It can’t be helped,” he replied, bravely.

“Her decision was final?”

“Quite.”

“You do not contemplate having another pop at her?”

“No good. I know when I’m licked.”

I patted him on the shoulder and said the only thing it seemed possible to say.

“After all, there is always golf.”

He nodded.

“Yes. My game needs a lot of tuning up. Now is the time to do it. From now on I go at this pastime seriously. I make it my life-work. Who knows?” he murmured, with a sudden gleam in his eyes. “The Amateur Championship——”

“The Open!” I cried, falling gladly into his mood.

“The American Amateur,” said Chester, flushing.

“The American Open,” I chorused.

“No one has ever copped all four.”

“No one.”

“Watch me!” said Chester Meredith, simply.

IT was about two weeks after this that I happened to look in on Chester at his house one morning. I found him about to start for the links. As he had foreshadowed in the conversation which I have just related, he now spent most of the daylight hours on the course. In these two weeks he had gone about his task of achieving perfection with a furious energy which made him the talk of the club. Always one of the best players in the place, he had developed an astounding brilliance. Men who had played him level were now obliged to receive two and even three strokes. The pro. himself, conceding one, had only succeeded in halving their match. The struggle for the President’s Cup came round once more, and Chester won it for the second time with ridiculous ease.

When I arrived, he was practising chip-shots in his sitting-room. I noticed that he seemed to be labouring under some strong emotion, and his first words gave me the clue.

“She’s going away to-morrow,” he said, abruptly, lofting a ball over the whatnot on to the Chesterfield.

I was not sure whether I was sorry or relieved. Her absence would leave a terrible blank, of course, but it might be that it would help him to get over his infatuation.

“Ah!” I said, non-committally.

Chester addressed his ball with a well-assumed phlegm, but I could see by the way his ears wiggled that he was feeling deeply. I was not surprised when he topped his shot into the coal-scuttle.

“She has promised to play a last round with me this morning,” he said.

Again I was doubtful what view to take. It was a pretty, poetic idea, not unlike Browning’s “Last Ride Together,” but I was not sure if it was altogether wise. However, it was none of my business, so I merely patted him on the shoulder and he gathered up his clubs and went off.

OWING to motives of delicacy I had not offered to accompany him on his round, and it was not till later that I learned the actual details of what occurred. At the start, it seems, the spiritual anguish which he was suffering had a depressing effect on his game. He hooked his drive off the first tee and was only enabled to get a five by means of a strong niblick shot out of the rough. At the second, the lake hole, he lost a ball in the water and got another five. It was only at the third that he began to pull himself together.

The test of a great golfer is his ability to recover from a bad start. Chester had this quality to a pre-eminent degree. A lesser man, conscious of being three over bogey for the first two holes, might have looked on his round as ruined. To Chester it simply meant that he had to get a couple of “birdies” right speedily, and he set about it at once. Always a long driver he excelled himself at the third. It is, as you know, an uphill hole all the way, but his drive could not have come far short of two hundred and fifty yards. A brassie-shot of equal strength and unerring direction put him on the edge of the green, and he holed out with a long putt two under bogey. He had hoped for a “birdie” and he had achieved an “eagle.”

I think that this splendid feat must have softened Felicia’s heart, had it not been for the fact that misery had by this time entirely robbed Chester of the ability to smile. Instead, therefore, of behaving in the wholesome, natural way of men who get threes at bogey five holes, he preserved a drawn, impassive countenance; and as she watched him tee up her ball, stiff, correct, polite, but to all outward appearance absolutely inhuman, the girl found herself stifling that thrill of what for a moment had been almost adoration. It was, she felt, exactly how her brother Crispin would have comported himself if he had done a hole in two under bogey.

And yet she could not altogether check a wistful sigh when, after a couple of fours at the next two holes, he picked up another stroke on the sixth and with an inspired spoon-shot brought his medal-score down to one better than bogey by getting a two at the hundred-and-seventy-yard seventh. But the brief spasm of tenderness passed, and when he finished the first nine with two more fours she refrained from anything warmer than a mere word of stereotyped congratulation.

“One under bogey for the first nine,” she said. “Splendid!”

“One under bogey!” said Chester, woodenly.

“Out in thirty-four. What is the record for the course?”

Chester started. So great had been his preoccupation that he had not given a thought to the course record. He suddenly realized now that the pro., who had done the lowest medal-score to date—the other course record was held by Peter Willard with a hundred and sixty-one, achieved in his first season—had gone out in only one better than his own figures that day.

“Sixty-eight,” he said.

“What a pity you lost those strokes at the beginning!”

“Yes,” said Chester.

He spoke absently—and, as it seemed to her, primly and without enthusiasm—for the flaming idea of having a go at the course record had only just occurred to him. Once before he had done the first nine in thirty-four, but on that occasion he had not felt that curious feeling of irresistible force which comes to a golfer at the very top of his form. Then he had been aware all the time that he had been putting chancily. They had gone in, yes, but he had uttered a prayer per putt. To-day he was superior to any weak doubtings. When he tapped the ball on the green, he knew it was going to sink. The course record? Why not? What a last offering to lay at her feet! She would go away, out of his life for ever; she would marry some other bird; but the memory of that supreme round would remain with her as long as she breathed. When he won the Open and Amateur for the second—the third—the fourth time, she would say to herself, “I was with him when he dented the record for his home course!” And he had only to pick up a couple of strokes on the last nine, to do threes at holes where he was wont to be satisfied with fours. Yes, by Vardon, he would take a whirl at it.

YOU, who are acquainted with these links, will no doubt say that the task which Chester Meredith had sketched out for himself—cutting two strokes off thirty-five for the second nine—was one at which Humanity might well shudder. The pro. himself, who had finished sixth in the last Open Championship, had never done better than a thirty-five, playing perfect golf and being one under bogey. But such was Chester’s mood that, as he teed up on the tenth, he did not even consider the possibility of failure. Every muscle in his body was working in perfect co-ordination with its fellows, his wrists felt as if they were made of tempered steel, and his eyes had just that hawk-like quality which enables a man to judge his short approaches to the inch. He swung forcefully, and the ball sailed so close to the direction-post that for a moment it seemed as if it had hit it.

“Oo!” cried Felicia.

Chester did not speak. He was following the flight of the ball. It sailed over the brow of the hill, and with his knowledge of the course he could tell almost the exact patch of turf on which it must have come to rest. An iron would do the business from there, and a single putt would give him the first of the “birdies” he required. Two minutes later he had holed out a six-foot putt for a three.

“Oo!” said Felicia again.

Chester walked to the eleventh tee in silence.

“No, never mind,” she said, as he stooped to put her ball on the sand. “I don’t think I’ll play any more. I’d much rather just watch you.”

“Oh, that you could watch me through life!” said Chester, but he said it to himself. His actual words were “Very well!” and he spoke them with a stiff coldness which chilled the girl.

The eleventh is one of the trickiest holes on the course, as no doubt you have found out for yourself. It looks absurdly simple, but that little patch of wood on the right that seems so harmless is placed just in the deadliest position to catch even the most slightly sliced drive. Chester’s lacked the austere precision of his last. A hundred yards from the tee it swerved almost imperceptibly, and, striking a branch, fell in the tangled undergrowth. It took him two strokes to hack it out and put it on the green, and then his long putt, after quivering on the edge of the hole, stayed there. For a swift instant red-hot words rose to his lips, but he caught them just as they were coming out and crushed them back. He looked at his ball and he looked at the hole.

“Tut!” said Chester.

Felicia uttered a deep sigh. That niblick-shot out of the rough had impressed her profoundly. If only, she felt, this superb golfer had been more human! Already, after watching him play the last nine holes, she had picked up more pointers about the game than the pro. of her home club had been able to teach her in six months. If only she were able to be constantly in this man’s society, to see exactly what it was that he did with his left wrist that gave that terrific snap to his drives, she might acquire the knack herself one of these days. For she was a clear-thinking, honest girl, and thoroughly realized that she did not get the distance she ought to with her wood. With a husband like Chester beside her to stimulate and advise, of what might she not be capable? If she got wrong in her stance, he could put her right with a word. If she had a bout of slicing, how quickly he would tell her what caused it. And she knew that she had only to speak a word to wipe out the effects of her refusal, to bring him to her side for ever.

But could a girl pay such a price? When he had got that “eagle” on the third, he had looked bored. When he had missed this last putt, he had not seemed to care. “Tut!” What a word to use at such a moment! No, she felt sadly, it could not be done. To marry Chester Meredith, she told herself, would be like marrying a composite of Soames Forsyte, Sir Willoughby Patterne, and all her brother Crispin’s friends. She sighed and was silent.

CHESTER, standing on the twelfth tee, reviewed the situation swiftly, like a general before a battle. There were seven holes to play, and he had to do these in two better than bogey. The one that faced him now offered few opportunities. It was a long, slogging, dog-leg hole, and even Ray and Taylor, when they had played their exhibition game on the course, had taken fives. No opening there.

The thirteenth—up a steep hill with a long iron-shot for one’s second and a blind green fringed with bunkers? Scarcely practicable to hope for better than a four. The fourteenth—into the valley with the ground sloping sharply down to the ravine? He had once done it in three, but it had been a fluke. No; on these three holes he must be content to play for a steady bogey and trust to picking up a stroke on the fifteenth.

The fifteenth, straightforward up to the plateau green with its circle of bunkers, presents few difficulties to the finished golfer who is on his game. A bunker meant nothing to Chester in his present conquering vein. His mashie-shot second soared almost contemptuously over the chasm and rolled to within a foot of the pin. He came to the sixteenth with the clear-cut problem before him of snipping two strokes off bogey on the last three holes.

To the unthinking man, not acquainted with the layout of our links, this would no doubt appear a tremendous feat. But the fact is, the Green Committee, with perhaps an unduly sentimental bias towards the happy ending, have arranged a comparatively easy finish to the course. The sixteenth is a perfectly plain hole with broad fairway and a down-hill run; the seventeenth, a one-shot affair with no difficulties for the man who keeps them straight; and the eighteenth, though its up-hill run makes it deceptive to the stranger and leads the unwary to take a mashie instead of a light iron for his second, has no real venom in it. Even Peter Willard has occasionally come home in a canter with a six, five, and seven, conceding himself only two eight-foot putts. It is, I think, this mild conclusion to a tough course that makes the refreshment-room of our club so noticeable for its sea of happy faces. The bar every day is crowded with rejoicing men who, forgetting the agonies of the first fifteen, are babbling of what they did on the last three. The seventeenth, with its possibilities of holing out a topped second, is particularly soothing.

Chester Meredith was not the man to top his second on any hole, so this supreme bliss did not come his way; but he laid a beautiful mashie-shot dead and got a three; and when with his iron he put his first well on the green at the seventeenth and holed out for a two, life, for all his broken heart, seemed pretty tolerable. He now had the situation well in hand. He had only to play his usual game to get a four on the last and lower the course record by one stroke.

It was at this supreme moment of his life that he ran into the Wrecking Crew.

You doubtless find it difficult to understand how it came about that if the Wrecking Crew were on the course at all he had not run into them long before. The explanation is that, with a regard for the etiquette of the game unusual in these miserable men, they had for once obeyed the law that enacts that foursomes shall start at the tenth. They had begun their dark work on the second nine, accordingly, at almost the exact moment when Chester Meredith was driving off at the first, and this had enabled them to keep ahead until now. When Chester came to the eighteenth tee, they were just leaving it, moving up the fairway with their caddies in mass formation and looking to his exasperated eye like one of those great race-migrations of the Middle Ages. Wherever Chester looked he seemed to see human, so to speak, figures. One was doddering about in the long grass fifty yards from the tee, others debouched to left and right. The course was crawling with them.

Chester sat down on the bench with a weary sigh. He knew these men. Self-centred, remorseless, deaf to all the promptings of their better nature, they never let anyone through. There was nothing to do but wait.

The Wrecking Crew scratched on. The man near the tee rolled his ball ten yards, then twenty, then thirty—he was improving. Ere long he would be out of range. Chester rose and swished his driver.

But the end was not yet. The individual operating in the rough on the left had been advancing in slow stages, and now, finding his ball teed up on a tuft of grass, he opened his shoulders and let himself go. There was a loud report, and the ball, hitting a tree squarely, bounded back almost to the tee, and all the weary work was to do again. By the time Chester was able to drive, he was reduced by impatience, and the necessity of refraining from commenting on the state of affairs as he would have wished to comment, to a frame of mind in which no man could have kept himself from pressing. He pressed, and topped. The ball skidded over the turf for a meagre hundred yards.

“D-d-d-dear me!” said Chester.

The next moment he uttered a bitter laugh. Too late a miracle had happened. One of the foul figures in front was waving its club. Other ghastly creatures were withdrawing to the side of the fairway. Now, when the harm had been done, these outcasts were signalling to him to go through. The hollow mockery of the thing swept over Chester like a wave. What was the use of going through now? He was a good three hundred yards from the green, and he needed bogey at this hole to break the record. Almost absently he drew his brassie from his bag; then, as the full sense of his wrongs bit into his soul, he swung viciously.

Golf is a strange game. Chester had pressed on the tee and foozled. He pressed now, and achieved the most perfect shot of his life. The ball shot from its place as if a charge of powerful explosive were behind it. Never deviating from a straight line, never more than six feet from the ground, it sailed up the hill, crossed the bunker, eluded the mounds beyond, struck the turf, rolled, and stopped fifty feet from the hole. It was the brassie-shot of a lifetime, and shrill senile yippings of excitement and congratulation floated down from the Wrecking Crew. For, degraded though they were, these men were not wholly devoid of human instincts.

Chester drew a deep breath. His ordeal was over. That third shot, which would lay the ball right up to the pin, was precisely the sort of thing he did best. Almost from boyhood he had been a wizard at the short approach. He could hole out in two now on his left ear. He strode up the hill to his ball. It could not have been lying better. Two inches away there was a nasty cup in the turf; but it had avoided this and was sitting nicely perched up, smiling an invitation to the mashie-niblick. Chester shuffled his feet and eyed the flag keenly. Then he stooped to play, and Felicia watched him breathlessly. Her whole being seemed to be concentrated on him. She had forgotten everything save that she was seeing a course record get broken. She could not have been more wrapped up in his success if she had had large sums of money on it.

THE Wrecking Crew, meanwhile, had come to life again. They had stopped twittering about Chester’s brassie-shot and were thinking of resuming their own game. Even in foursomes where fifty yards is reckoned a good shot somebody must be away, and the man whose turn it was to play was the one who had acquired from his brother-members of the club the nickname of the First Grave-Digger.

A word about the human wen. He was—if there can be said to be grades in such a sub-species—the star performer of the Wrecking Crew. The lunches of fifty-seven years had caused his chest to slip down into the mezzanine floor, but he was still a powerful man, and had in his youth been a hammer-thrower of some repute. He differed from his colleagues—the Man With the Hoe, Old Father Time, and Consul, the Almost Human—in that, while they were content to peck cautiously at the ball, he never spared himself in his efforts to do it a violent injury. Frequently he had cut a blue dot almost in half with his niblick. He was completely muscle-bound, so that he seldom achieved anything beyond a series of chasms in the turf, but he was always trying, and it was his secret belief that, given two or three miracles happening simultaneously, he would one of these days bring off a snifter. Years of disappointment had, however, reduced the flood of hope to a mere trickle, and when he took his brassie now and addressed the ball he had no immediate plans beyond a vague intention of rolling the thing a few yards farther up the hill.

The fact that he had no business to play at all till Chester had holed out did not occur to him; and even if it had occurred he would have dismissed the objection as finicking. Chester, bending over his ball, was nearly two hundred yards away—or the distance of three full brassie-shots. The First Grave-Digger did not hesitate. He whirled up his club as in distant days he had been wont to swing the hammer, and, with the grunt which this performance always wrung from him, brought it down.

Golfers—and I stretch this term to include the Wrecking Crew—are a highly imitative race. The spectacle of a flubber flubbing ahead of us on the fairway inclines to make us flub as well; and, conversely, it is immediately after we have seen a magnificent shot that we are apt to eclipse ourselves. Consciously the Grave-Digger had no notion how Chester had made that superb brassie-biff of his, but all the while I suppose his subconscious self had been taking notes. At any rate, on this one occasion he, too, did the shot of a lifetime. As he opened his eyes, which he always shut tightly at the moment of impact, and started to unravel himself from the complicated tangle in which his follow-through had left him, he perceived the ball breasting the hill like some untamed jack-rabbit of the Californian prairie.

For a moment his only emotion was one of dreamlike amazement. He stood looking at the ball with a wholly impersonal wonder, like a man suddenly confronted with some terrific work of Nature. Then, as a sleep-walker awakens, he came to himself with a start. Directly in front of the flying pilule was a man bending to make an approach-shot.

Chester, always a concentrated golfer when there was man’s work to do, had scarcely heard the crack of the brassie behind him. Certainly he had paid no attention to it. His whole mind was fixed on his stroke. He measured with his eye the distance to the pin, noted the down-slope of the green, and shifted his stance a little to allow for it. Then, with a final swift waggle, he laid his club-head behind the ball and slowly raised it. It was just coming down when the world became full of shouts of “Fore!” and something hard smote him violently on the seat of his plus-fours.

THE supreme tragedies of life leave us momentarily stunned. For an instant which seemed an age Chester could not understand what had happened. True, he realized that there had been an earthquake, a cloud-burst, and a railway accident, and that a high building had fallen on him at the exact moment when somebody had shot him with a gun, but these happenings would account for only a small part of his sensations. He blinked several times, and rolled his eyes wildly. And it was while rolling them that he caught sight of the gesticulating Wrecking Crew on the lower slopes and found enlightenment. Simultaneously, he observed his ball only a yard and a half from where it had been when he addressed it.

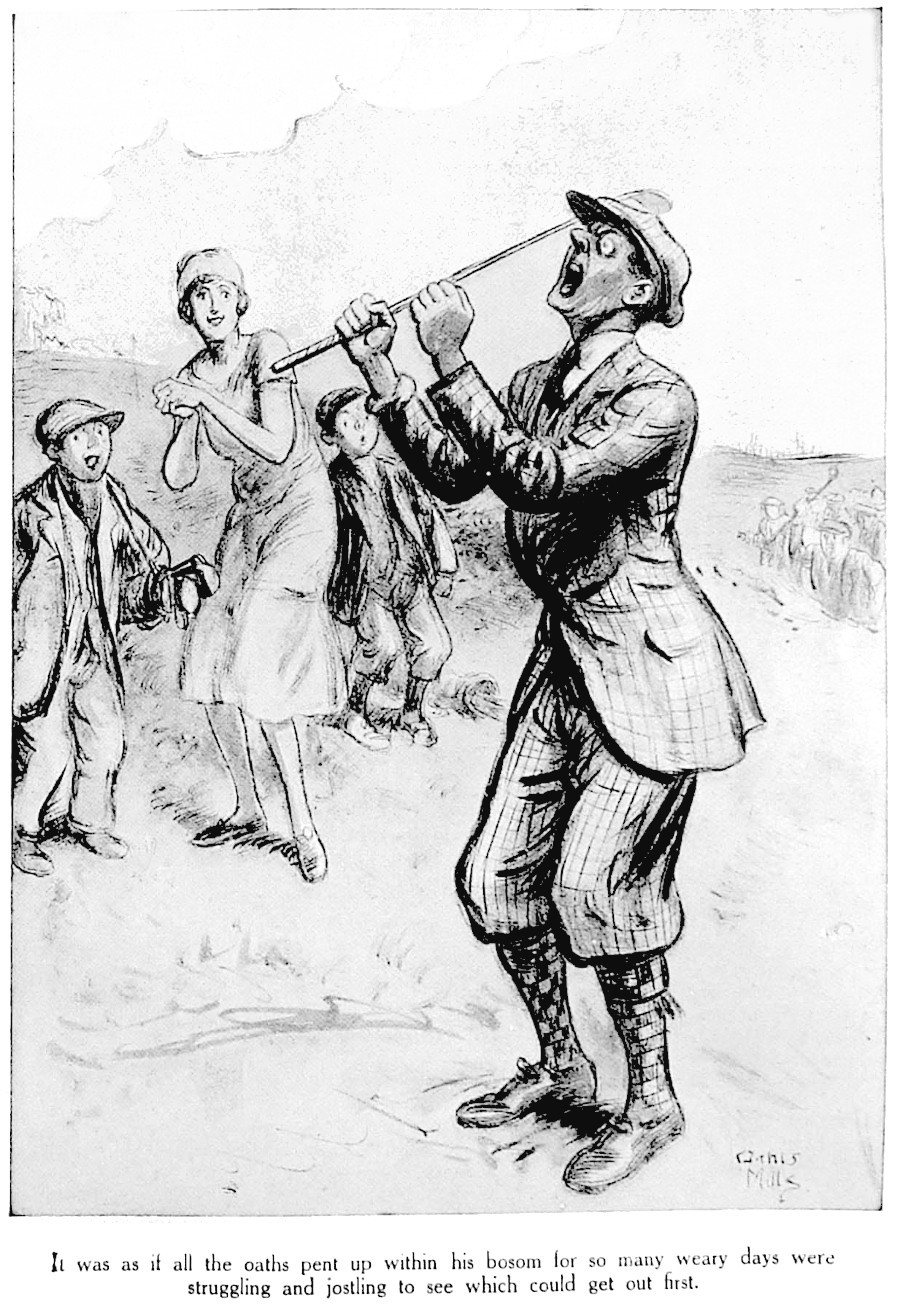

Chester Meredith gave one look at his ball, one look at the flag, one look at the Wrecking Crew, one look at the sky. His lips writhed, his forehead turned vermilion. Beads of perspiration started out on his forehead. And then, with his whole soul seething like a cistern struck by a thunderbolt, he spoke.

“! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !” cried Chester.

Dimly he was aware of a wordless exclamation from the girl beside him, but he was too distraught to think of her now. It was as if all the oaths pent up within his bosom for so many weary days were struggling and jostling to see which could get out first. They cannoned into each other, they linked hands and formed parties, they got themselves all mixed up in weird vowel-sounds, the second syllable of some red-hot verb forming a temporary union with the first syllable of some blistering noun.

“——! ——!! ——!!! ——!!!! ——!!!!!” cried Chester.

Felicia stood staring at him. In her eyes was the look of one who sees visions.

“ *** !!! *** !!! *** !!! *** !!!” roared Chester, in part.

A great wave of emotion flooded over the girl. How she had misjudged this silver-tongued man! She shivered as she thought that, had this not happened, in another five minutes they would have parted for ever, sundered by seas of misunderstanding, she cold and scornful, he with all his music still within him.

“Oh, Mr. Meredith!” she cried, faintly.

With a sickening abruptness Chester came to himself. It was as if somebody had poured a pint of ice-cold water down his back. He blushed vividly. He realized with horror and shame how grossly he had offended against all the canons of decency and good taste. He felt like the man in one of those “What Is Wrong With This Picture?” things in the advertisements of the etiquette-books.

“I beg—I beg your pardon!” he mumbled, humbly. “Please, please, forgive me. I should not have spoken like that.”

“You should! You should!” cried the girl, passionately. “You should have said all that and a lot more. That awful man ruining your record round like that! Oh, why am I a poor weak woman with practically no vocabulary that’s any use for anything?”

Quite suddenly, without knowing that she had moved, she found herself at his side, holding his hand.

“Oh, to think how I misjudged you!” she wailed. “I thought you cold, stiff, formal, precise. I hated the way you sniggered when you foozled a shot. I see it all now! You were keeping it in for my sake. Can you ever forgive me?”

Chester, as I have said, was not a very quick-minded young man, but it would have taken a duller youth than he to fail to read the message in the girl’s eyes, to miss the meaning of the pressure of her hand on his.

“My gosh!” he exclaimed, wildly. “Do you mean——? Do you think——? Do you really——? Honestly, has this made a difference? Is there any chance for a fellow, I mean?”

Her eyes helped him on. He felt suddenly confident and masterful.

“Look here—no kidding—will you marry me?” he said.

“I will! I will!”

“Darling!” cried Chester.

He would have said more, but at this point he was interrupted by the arrival of the Wrecking Crew, who panted up full of apologies; and Chester, as he eyed them, thought that he had never seen a nicer, cheerier, pleasanter lot of fellows in his life. His heart warmed to them. He made a mental resolve to hunt them up some time and have a good long talk. He waved the Grave-Digger’s remorse airily aside.

“Don’t mention it,” he said. “Not at all. Faults on both sides. By the way, my fiancée, Miss Blakeney.”

The Wrecking Crew puffed acknowledgment.

“But, my dear fellow,” said the Grave-Digger, “it was—really it was—unforgivable. Spoiling your shot. Never dreamed I would send the ball that distance. Lucky you weren’t playing an important match.”

“But he was,” moaned Felicia. “He was trying for the course record, and now he can’t break it.”

The Wrecking Crew paled behind their whiskers, aghast at this tragedy, but Chester, glowing with the yeasty intoxication of love, laughed lightly.

“What do you mean, can’t break it?” he cried, cheerily. “I’ve one more shot.”

And, carelessly addressing the ball, he holed out with a light flick of his mashie-niblick.

“CHESTER, darling!” said Felicia.

They were walking slowly through a secluded glade in the quiet evenfall.

“Yes, precious?”

Felicia hesitated. What she was going to say would hurt him, she knew, and her love was so great that to hurt him was agony.

“Do you think——” she began. “I wonder whether—— It’s about Crispin.”

“Good old Crispin!”

Felicia sighed, but the matter was too vital to be shirked. Cost what it might, she must speak her mind.

“Chester, darling, when we are married, would you mind very, very much if we didn’t have Crispin with us all the time?”

Chester started.

“Good Lord!” he exclaimed. “Don’t you like him?”

“Not very much,” confessed Felicia. “I don’t think I’m clever enough for him. I’ve rather disliked him ever since we were children. But I know what a friend he is of yours——”

Chester uttered a joyous laugh.

“Friend of mine! Why, I can’t stand the blighter! I loathe the worm! I abominate the excrescence! I only pretended we were friends because I thought it would put me in solid with you. The man is a pest and should have been strangled at birth. At school I used to kick him every time I saw him. If your brother Crispin tries so much as to set foot across the threshold of our little home, I’ll set the dog on him.”

“My hero!” whispered Felicia. “We shall be very, very happy.” She drew her arm through his. “Tell me, dearest,” she murmured, “all about how you used to kick Crispin at school.”

And together they wandered off into the sunset.

Annotations to this story can be found on the American magazine version of the story, from the Saturday Evening Post of July 7, 1923.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums