The Strand Magazine, May 1920

RCHIE MOFFAM inserted a fresh cigarette in his long holder

and gazed rather wistfully across the table at his friend, Roscoe Sherriff,

the Press-agent. They had just finished lunch, and during the meal Sherriff,

who, like most men of action, was fond of hearing his own voice and liked

exercising it on the subject of himself, had been telling Archie a few

anecdotes about his professional past. From these the latter had conceived

a picture of Roscoe Sherriff’s life as a prismatic thing of energy

and adventure—just the sort of life, in fact, which he would have

enjoyed leading himself. He wished that he, too, like the Press-agent,

could go about the place “slipping things over” and “putting

things across.”

RCHIE MOFFAM inserted a fresh cigarette in his long holder

and gazed rather wistfully across the table at his friend, Roscoe Sherriff,

the Press-agent. They had just finished lunch, and during the meal Sherriff,

who, like most men of action, was fond of hearing his own voice and liked

exercising it on the subject of himself, had been telling Archie a few

anecdotes about his professional past. From these the latter had conceived

a picture of Roscoe Sherriff’s life as a prismatic thing of energy

and adventure—just the sort of life, in fact, which he would have

enjoyed leading himself. He wished that he, too, like the Press-agent,

could go about the place “slipping things over” and “putting

things across.”

“The more I see of America,” sighed Archie, “the more it amazes me. Absolutely! All you birds seem to have been doing things from the cradle upwards. I wish I could do things!”

“Well, why don’t you?”

Archie flicked the ash from his cigarette into the finger-bowl.

“Oh, I don’t know, you know,” he said. “Somehow, none of our family ever have. I don’t know why it is, but whenever a Moffam starts out to do things he infallibly makes a bloomer. There was a Moffam in the Middle Ages who had a sudden spasm of energy and set out to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, dressed as a wandering friar. Rum ideas they had in those days.”

“Did he get there?”

“Absolutely not! Just as he was leaving the front door his favourite hound mistook him for a tramp—or a varlet, or a scurvy knave, or whatever they used to call them at that time—and bit him in the fleshy part of the leg.”

“Well, at least he started.”

“Enough to make a chappie start, what?”

Roscoe Sherriff sipped his coffee thoughtfully. He was an apostle of Energy, and it seemed to him that he could make a convert of Archie and incidentally do himself a bit of good. For several days he had been looking for someone like Archie to help him in a small matter which he had in mind.

“If you’re really keen on doing things,” he said, “there’s something you can do for me right away.”

Archie beamed.

“Anything, dear boy, anything! State your case!”

“Would you have any objection to putting up a snake for me?”

“Putting up a snake?”

“Just for a day or two.”

“But how do you mean, old soul? Put him up where?”

“Wherever you live. Where do you live? The Cosmopolis, isn’t it? Of course! You married old Brewster’s daughter. I remember reading about it.”

“But, I say, laddie, I don’t want to spoil your day and disappoint you and so forth, but my jolly old father-in-law would never let me keep a snake. Why, it’s as much as I can do sometimes to make him let me stop on in the place.”

“He wouldn’t know.”

“There’s not much that goes on in the hotel that he doesn’t know,” said Archie, doubtfully.

“He mustn’t know. The whole point of the thing is that it must be a dead secret.”

Archie flicked some more ash into the finger-bowl.

“I don’t seem absolutely to have grasped the affair in all its aspects, if you know what I mean,” he said. “I mean to say—in the first place—why would it brighten your young existence if I entertained this snake of yours?”

“It’s not mine. It belongs to Mme. Brudowska. You’ve heard of her, of course?’

“Oh, yes. She’s some sort of performing snake female in vaudeville or something, isn’t she, or something of that species or order?”

“You’re near it, but not quite right. She is the leading exponent of high-brow tragedy on any stage in the civilized world.”

“Absolutely! I remember now. My wife lugged me to see her perform one night. It all comes back to me. She had me wedged in an orchestra-stall before I knew what I was up against, and then it was too late. I remember reading in some journal or other that she had a pet snake, given her by some Russian prince or other, what?”

“That,” said Sherriff, “was the impression I intended to convey when I sent the story to the papers. I’m her Press-agent. As a matter of fact, I bought Peter—its name’s Peter—myself down on the East Side. I always believe in animals for Press-agent stunts. I’ve nearly always had good results. But with Her Nibs I’m handicapped. Shackled, so to speak. You might almost say my genius is stifled. Or strangled, if you prefer it.”

“Anything you say,” agreed Archie, courteously. “But how? Why is your what-d’you-call-it what’s-its-named?”

“She keeps me on a leash. She won’t let me do anything with a kick in it. If I’ve suggested one rip-snorting stunt, I’ve suggested twenty, and every time she turns them down on the ground that that sort of thing is beneath the dignity of an artist in her position. It doesn’t give a fellow a chance. So now I’ve made up my mind to do her good by stealth. I’m going to steal her snake.”

“Steal it? Pinch it, as it were?”

“Yes. Big story for the papers, you see. She’s grown very much attached to Peter. He’s her mascot. I believe she’s practically kidded herself into believing that Russian prince story. If I can sneak it away and keep it away for a day or two, she’ll do the rest. She’ll make such a fuss that the papers will be full of it.”

“I see.”

“Now, any ordinary woman would work in with me. But not Her Nibs. She would call it cheap and degrading and a lot of other things. It’s got to be a genuine steal, and, if I’m caught at it, I lose my job. So that’s where you come in.”

“But where am I to keep the jolly old reptile?”

“Oh, anywhere. Punch a few holes in a hat-box, and make it up a shake-down inside. It’ll be company for you.”

“Something in that. My wife’s away just now and it’s a bit lonely in the evenings.”

“You’ll never be lonely with Peter around. He’s a great scout. Always merry and bright.”

“He doesn’t bite, I suppose, or sting or what-not?”

“He may what-not occasionally. It depends on the weather. But, outside of that, he’s as harmless as a canary.”

“Dashed dangerous things, canaries,” said Archie, thoughtfully. “They peck at you.”

“Don’t weaken!” pleaded the Press-agent.

“Oh, all right. I’ll take him. By the way, touching the matter of browsing and sluicing. What do I feed him on?”

“Oh, anything. Bread-and-milk or fruit or soft-boiled egg or dog-biscuit or ants’-eggs. You know—anything you have yourself. Well, I’m much obliged for your hospitality. I’ll do the same for you another time. Now I must be getting along to see to the practical end of the thing. By the way, Her Nibs lives at the Cosmopolis, too. Very convenient. Well, so long. See you later.”

Archie, left alone, began for the first time to have serious doubts. He had allowed himself to be swayed by Mr. Sherriff’s magnetic personality, but now that the other had removed himself he began to wonder if he had been entirely wise to lend his sympathy and co-operation to the scheme. He had never had intimate dealings with a snake before, but he had kept silkworms as a child, and there had been the deuce of a lot of fuss and unpleasantness over them. Getting into the salad and what-not. Something seemed to tell him that he was asking for trouble with a loud voice, but he had given his word and he supposed he would have to go through with it.

He lit another cigarette and wandered out into Fifth Avenue. His usually smooth brow was ruffled with care. Despite the eulogies which Sherriff had uttered concerning Peter, he found his doubts increasing. Peter might, as the Press-agent had stated, be a great scout, but was his little Garden of Eden on the fifth floor of the Cosmopolis Hotel likely to be improved by the advent of even the most amiable and winsome of serpents? However——

“Moffam! My dear fellow!”

The voice, speaking suddenly in his ear from behind, roused Archie from his reflections. Indeed, it roused him so effectually that he jumped a clear inch off the ground and bit his tongue. Revolving on his axis, he found himself confronting a middle-aged man with a face like a horse. The man was dressed in something of an old-world style. His clothes had an English cut. He had a drooping grey moustache. He also wore a grey bowler hat flattened at the crown—but who are we to judge him?

“Archie Moffam! I have been trying to find you all the morning.”

Archie had placed him now. He had not seen General Mannister for several years—not, indeed, since the days when he used to meet him at the home of young Lord Seacliff, his nephew. Archie had been at Eton and Oxford with Seacliff, and had often visited him in the Long Vacation.

“Halloa, General! What ho, what ho! What on earth are you doing over here?”

“Let’s get out of this crush, my boy.” General Mannister steered Archie into a side-street. “That’s better.” He cleared his throat once or twice, as if embarrassed. “I’ve brought Seacliff over,” he said, finally.

“Dear old Squiffy here? Oh, I say! Great work!”

General Mannister did not seem to share his enthusiasm. He looked like a horse with a secret sorrow. He coughed three times, like a horse who, in addition to a secret sorrow, had contracted asthma.

“You will find Seacliff changed,” he said. “Let me see, how long is it since you and he met?”

Archie reflected.

“I was demobbed just about a year ago. I saw him in Paris about a year before that. The old egg got a bit of shrapnel in his foot or something, didn’t he? Anyhow, I remember he was sent home.”

“His foot is perfectly well again now. But, unfortunately, the enforced inaction led to disastrous results. You recollect, no doubt, that Seacliff always had a—a tendency—a—a weakness—it was a family failing——”

“Mopping it up, do you mean? Shifting it? Looking on the jolly old stuff when it was red and what-not, what?”

“Exactly.”

Archie nodded.

“Dear old Squiffy was always rather a lad for the wassail-bowl. When I met him in Paris, I remember, he was quite tolerably blotto.”

“Precisely. And the failing has, I regret to say, grown on him since he returned from the war. My poor sister was extremely worried. In fact, to cut a long story short, I induced him to accompany me to America. I am attached to the British Legation in Washington now, you know.”

“Oh, really?”

“I wished Seacliff to come with me to Washington, but he insists on remaining in New York. He stated specifically that the thought of living in Washington gave him the—what was the expression he used?”

“The pip?”

“The pip. Precisely.”

“But what was the idea of bringing him to America?”

“This admirable Prohibition enactment has rendered America—to my mind—the ideal place for a young man of his views.” The General looked at his watch. “It is most fortunate that I happened to run into you, my dear fellow. My train for Washington leaves in another hour, and I have packing to do. I want to leave poor Seacliff in your charge while I am gone.”

“Oh, I say! What!”

“You can look after him. I am credibly informed that even now there are places in New York where a determined young man may obtain the—er—stuff, and I should be infinitely obliged—and my poor sister would be infinitely grateful—if you would keep an eye on him.” He hailed a taxi-cab. “I am sending Seacliff round to the Cosmopolis to-night. I am sure you will do everything you can. Good-bye, my boy, good-bye.”

Archie continued his walk. This, he felt, was beginning to be a bit thick. He smiled a bitter, mirthless smile as he recalled the fact that less than half an hour had elapsed since he had expressed a regret that he did not belong to the ranks of those who do things. Fate since then had certainly supplied him with jobs with a lavish hand. By bed-time he would be an active accomplice to a theft, valet and companion to a snake he had never met, and—as far as he could gather the scope of his duties—a combination of nursemaid and private detective to Dear Old Squiffy.

It was past four o’clock when he returned to the Cosmopolis. Roscoe Sherriff was pacing the lobby of the hotel nervously, carrying a small hand-bag.

“Here you are at last! Good heavens, man, I’ve been waiting two hours.”

“Sorry, old bean. I was musing a bit and lost track of the time.”

The Press-agent looked cautiously round. There was nobody within earshot.

“Here he is!” he said.

“Here he is!” he said.

“Who?”

“Peter.”

“Where?” said Archie, staring blankly.

“In this bag. Did you expect to find him strolling arm-in-arm with me round the lobby? Here you are! Take him!”

He was gone. And Archie, holding the bag, made his way to the lift. The bag squirmed gently in his grip.

The only other occupant of the lift was a striking-looking woman of foreign appearance, dressed in a way that made Archie feel that she must be somebody or she couldn’t look like that. Her face, too, seemed vaguely familiar. She entered the lift at the second floor where the tea-room is, and she had the contented expression of one who had tea’d to her satisfaction. She got off at the same floor as Archie, and walked swiftly, in a lithe, pantherish way, round the bend in the corridor. Archie followed more slowly. When he reached the door of his room, the passage was empty. He inserted the key in his door, turned it, pushed the door open, and pocketed the key. He was about to enter when the bag again squirmed gently in his grip.

From the days of Pandora, through the epoch of Bluebeard’s wife, down to the present time, one of the chief failings of humanity has been the disposition to open things that were better closed. It would have been simple for Archie to have taken another step and put a door between himself and the world, but there came to him the irresistible desire to peep into the bag now—not three seconds later, but now. All the way up in the lift he had been battling with the temptation, and now he succumbed.

The bag was one of those simple bags with a thingummy which you press. Archie pressed it. And, as it opened, out popped the head of Peter. His eyes met Archie’s. Over his head there seemed to be an invisible mark of interrogation. His gaze was curious, but kindly. He appeared to be saying to himself, “Have I found a friend?”

Serpents, or Snakes, says the Encyclopædia, are reptiles of the saurian class Ophidia, characterized by an elongated, cylindrical, limbless, scaly form, and distinguished from lizards by the fact that the halves (rami) of the lower jaw are not solidly united at the chin, but movably connected by an elastic ligament. The vertebræ are very numerous, gastrocentrous, and procœlos. And, of course, when they put it like that, you can see at once that a man might spend hours with combined entertainment and profit just looking at a snake.

Archie would no doubt have done this: but long before he had time really to inspect the halves (rami) of his new friend’s lower jaw and to admire its elastic fittings, and long before the gastrocentrous and procœlos character of the other’s vertebræ had made any real impression on him, a piercing scream almost at his elbow startled him out of his scientific reverie. A door opposite had opened, and the woman of the elevator was standing staring at him with an expression of horror and fury that went through him like a knife. It was the expression which, more than anything else, had made Mme. Brudowska what she was professionally. Combined with a deep voice and a sinuous walk, it enabled her to draw down a matter of a thousand dollars per week.

Indeed, though the fact gave him little pleasure, Archie, as a matter of fact, was at this moment getting about—including war-tax—two dollars and seventy-five cents’ worth of the great emotional star for nothing. For, having treated him gratis to the look of horror and fury, she now moved towards him with the sinuous walk and spoke in the tone which she seldom permitted herself to use before the curtain of act two, unless there was a whale of a situation that called for it in act one.

“Thief!”

It was the way she said it.

Archie staggered backwards through the open door of his room, kicked it to with a flying foot, and sat down on the bed. Peter, the snake, who had fallen on the floor with a squashy sound, looked surprised and pained for a moment, and then, being a philosopher at heart, cheered up and began hunting for flies under the bureau.

Peril sharpens the intellect. Archie’s mind as a rule worked in rather a languid and restful sort of way, but now it got going with a rush and a whir. He glared round the room. He had never seen a room so devoid of satisfactory cover. And then there came to him a scheme, a ruse. It offered a chance of escape. It was, indeed, a bit of all right.

Peter, the snake, loafing contentedly about the carpet, found himself seized by what the Encyclopædia calls the “distensible gullet” and looked up reproachfully. The next moment he was in his bag again: and Archie, bounding silently into the bathroom, was tearing the cord off his dressing-gown.

There came a banging at the door. A voice spoke sternly. A masculine voice this time.

“Say! Open this door!”

Archie rapidly attached the dressing-gown cord to the handle of the bag, leaped to the window, opened it, tied the cord to a projecting piece of iron on the sill, lowered Peter and the bag into the depths, and closed the window again. The whole affair took but a few seconds. Generals have received the thanks of their nations for displaying less resource on the field of battle.

He opened the door. Outside stood the bereaved woman, and beside her a bullet-headed gentleman with a bowler hat on the back of his head, in whom Archie recognized the hotel detective.

The hotel detective also recognized Archie, and the stern cast of his features relaxed. He even smiled a rusty but propitiatory smile. He imagined—erroneously—that Archie, being the son-in-law of the owner of the hotel, had a pull with that gentleman: and he resolved to proceed warily lest he jeopardize his job.

“Why, Mr. Moffam!” he said, apologetically. “I didn’t know it was you I was disturbing.”

“Always glad to have a chat,” said Archie, cordially. “What seems to be the trouble?”

“My snake!” cried the queen of tragedy. “Where is my snake?”

Archie looked at the detective. The detective looked at Archie.

“This lady,” said the detective, with a dry little cough, “thinks her snake is in your room, Mr. Moffam.”

“Snake?”

“Snake’s what the lady said.”

“My snake! My Peter!” Mme. Brudowska’s voice shook with emotion. “He is here, here in this room.”

Archie shook his head.

“No snakes here! Absolutely not! I remember noticing when I came in.”

“The snake is here, here in this room. This man had it in a bag! I saw him! He is a thief!”

“Easy, ma’am!” protested the detective. “Go easy! This gentleman is the boss’s son-in-law.”

“I care not who he is! He has my snake! Here, here in this room!”

“Mr. Moffam wouldn’t go round stealing snakes.”

“Rather not,” said Archie. “Never stole a snake in my life. None of the Moffams have ever gone about stealing snakes. Regular family tradition! Though I once had an uncle who kept goldfish.”

“He is here! Here! My Peter!”

Archie looked at the detective. The detective looked at Archie. “We must humour her!” their glances said.

“Of course,” said Archie, “if you’d like to search the room, what? What I mean to say is, this is Liberty Hall. Everybody welcome! Bring the kiddies!”

“I will search the room!” said Mme. Brudowska.

The detective glanced apologetically at Archie.

“Don’t blame me for this, Mr. Moffam,” he urged.

“Rather not! Only too glad you’ve dropped in!”

He took up an easy attitude against the window, and watched the empress of the emotional drama explore. Presently she desisted, baffled. For an instant she paused, as though about to speak, then swept from the room. A moment later a door banged across the passage.

“How do they get that way?” queried the detective.

“The female of the species is more deadly than the male,” said Archie.

“It’s the hot weather,” said the detective, judicially. “Well, g’bye, Mr. Moffam. Sorry to have butted in.”

The door closed. Archie waited a few moments, then went to the window and hauled in the slack. Presently the bag appeared over the edge of the window-sill.

“Good God!” said Archie.

In the rush and swirl of recent events he must have omitted to see that the clasp that fastened the bag was properly closed: for the bag, as it jumped on to the window-sill, gaped at him like a yawning face. And inside it there was nothing.

Archie leaned as far out of the window as he could manage without committing suicide. Far below him, the traffic took its usual course and the pedestrians moved to and fro upon the pavements. There was no crowding, no excitement. Yet only a few moments before a long green snake with three hundred ribs, a distensible gullet, and gastrocentrous vertebræ must have descended on that street like the gentle rain from heaven upon the place beneath. And nobody seemed even interested. Not for the first time since he had arrived in America, Archie marvelled at the cynical detachment of the New Yorker, who permits himself to be surprised at nothing.

He shut the window and moved away with a heavy heart. He had not had the pleasure of an extended acquaintanceship with Peter, but he had seen enough of him to realize his sterling qualities. Somewhere beneath Peter’s three hundred ribs there had lain a heart of gold, and Archie mourned for his loss.

Archie had a dinner and theatre engagement that night, and it was late when he returned to the hotel. He found his father-in-law prowling restlessly about the lobby. There seemed to be something on Mr. Brewster’s mind. He came up to Archie with a brooding frown on his square face.

“Who’s this man Seacliff?” he demanded, without preamble. “I hear he’s a friend of yours.”

“Oh, you’ve met him, what?” said Archie. “Had a nice little chat together, yes? Talked of this and that, no?”

“We have not said a word to each other.”

“Really? Oh, well, dear old Squiffy is one of those strong, silent fellers, you know. You mustn’t mind if he’s a bit dumb. He never says much, but it’s whispered round the clubs that he thinks a lot. It was rumoured in the Spring of nineteen-thirteen that Squiffy was on the point of making a bright remark, but it never came to anything.”

Mr. Brewster struggled with his feelings.

“Who is he? You seem to know him.”

“Oh, yes. Great pal of mine, Squiffy. We went through Eton, Oxford, and the Bankruptcy Court together. And here’s a rummy coincidence. When they examined me, I had no assets. And, when they examined Squiffy, he had no assets! Rather extraordinary, what?”

Mr. Brewster seemed to be in no mood for discussing coincidences.

“I might have known he was a friend of yours!” he said, bitterly. “Well, if you want to see him, you’ll have to do it outside my hotel.”

“Why, I thought he was stopping here.”

“He is—to-night. To-morrow he can look for some other hotel to break up.”

“Great Scot! Has dear old Squiffy been breaking the place up?”

Mr. Brewster snorted.

“I am informed that this precious friend of yours entered my grill-room at eight o’clock. He must have been completely intoxicated, though the head waiter tells me he noticed nothing at the time.”

Archie nodded approvingly.

“Dear old Squiffy was always like that. It’s a gift. However woozled he might be, it was impossible to detect it with the naked eye. I’ve seen the dear old chap many a time whiffled to the eyebrows, and looking as sober as a bishop. Soberer! When did it begin to dawn on the lads in the grill-room that the old egg had been pushing the boat out?”

“The head waiter,” said Mr. Brewster, with cold fury, “tells me that he got a hint of the man’s condition when he suddenly got up from his table and went the round of the room, pulling off all the table-cloths and breaking everything that was on them. He then threw a number of rolls at the diners, and left. He seems to have gone straight to bed.”

“Dashed sensible of him, what? Sound, practical chap, Squiffy. But where on earth did he get the—er—materials?”

“From his room. I made inquiries. He has six large cases in his room.”

“Squiffy always was a chap of infinite resource! Well, I’m dashed sorry this should have happened, don’t you know.”

“If it hadn’t been for you, the man would never have come here.” Mr. Brewster brooded coldly. “I don’t know why it is, but ever since you came to this hotel I’ve had nothing but trouble.”

“Dashed sorry!” said Archie, sympathetically.

“Grrh!” said Mr. Brewster.

Archie made his way meditatively to the lift. The injustice of his father-in-law’s attitude pained him. It was absolutely rotten and all that to be blamed for everything that went wrong in the Hotel Cosmopolis.

While this conversation was in progress, Lord Seacliff was enjoying a refreshing sleep in his room on the fourth floor. Two hours passed. The noise of the traffic in the street below faded away. Only the rattle of an occasional belated cab broke the silence. In the hotel all was still. Mr. Brewster had gone to bed. Archie, in his room, smoked meditatively. Peace may have been said to reign.

At half-past two Lord Seacliff awoke. His hours of slumber were always irregular. He sat up in bed and switched the light on. He was a shock-headed young man with a red face and a hot brown eye. He yawned and stretched himself. His head was aching a little. The room seemed to him a trifle close. He got out of bed and threw open the window. Then, returning to bed, he picked up a book and began to read. He was conscious of feeling a little jumpy, and reading generally sent him to sleep.

Much has been written on the subject of bed-books. The general consensus of opinion is that a gentle, slow-moving story makes the best opiate. If this be so, dear old Squiffy’s choice of literature had been rather injudicious. His book was “The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes,” and the particular story which he selected for perusal was the one entitled “The Speckled Band.” He was not a great reader, but, when he read, he liked something with a bit of zip to it.

Squiffy became absorbed. He had read the story before, but a long time back, and its complications were fresh to him. The tale, it may be remembered, deals with the activities of an ingenious gentleman who kept a snake, and used to loose it into people’s bedrooms as a preliminary to collecting on their insurance. It gave Squiffy pleasant thrills, for he had always had a particular horror of snakes. As a child, he had shrunk from visiting the serpent house at the Zoo: and, later, when he had come to man’s estate and had put off childish things, and settled down in real earnest to his self-appointed mission of drinking up all the alcoholic fluid in England, the distaste for Ophidia had lingered. To a dislike for real snakes had been added a maturer shrinking from those which existed only in his imagination. He could still recall his emotions on the occasion, scarcely three months before, when he had seen a long, green serpent which a majority of his contemporaries had assured him wasn’t there. Squiffy read on:—

“Suddenly another sound became audible—a very gentle, soothing sound, like that of a small jet of steam escaping continuously from a kettle.”

Lord Seacliff looked up from his book with a start. Imagination was beginning to play him tricks. He could have sworn that he had actually heard that identical sound. It had seemed to come from the window. He listened again. No! All was still. He returned to his book and went on reading.

“It was a singular sight that met our eyes. Beside

the table, on a wooden chair, sat Doctor Grimesby Rylott, clad in a long

dressing-gown. His chin was cocked upward and his eyes were fixed in a

dreadful, rigid stare at the corner of the ceiling. Round his brow he had

a peculiar yellow band, with brownish speckles, which seemed to be bound

tightly round his head.

“I took a step forward. In an instant his strange

headgear began to move, and there reared itself from among his hair the

squat, diamond-shaped head and puffed neck of a loathsome serpent. . . .”

“Ugh!” said Squiffy. He closed the book and put it down. His head was aching worse than ever. He wished now that he had read something else. No fellow could read himself to sleep with this sort of thing. Blighters ought not to write this sort of thing.

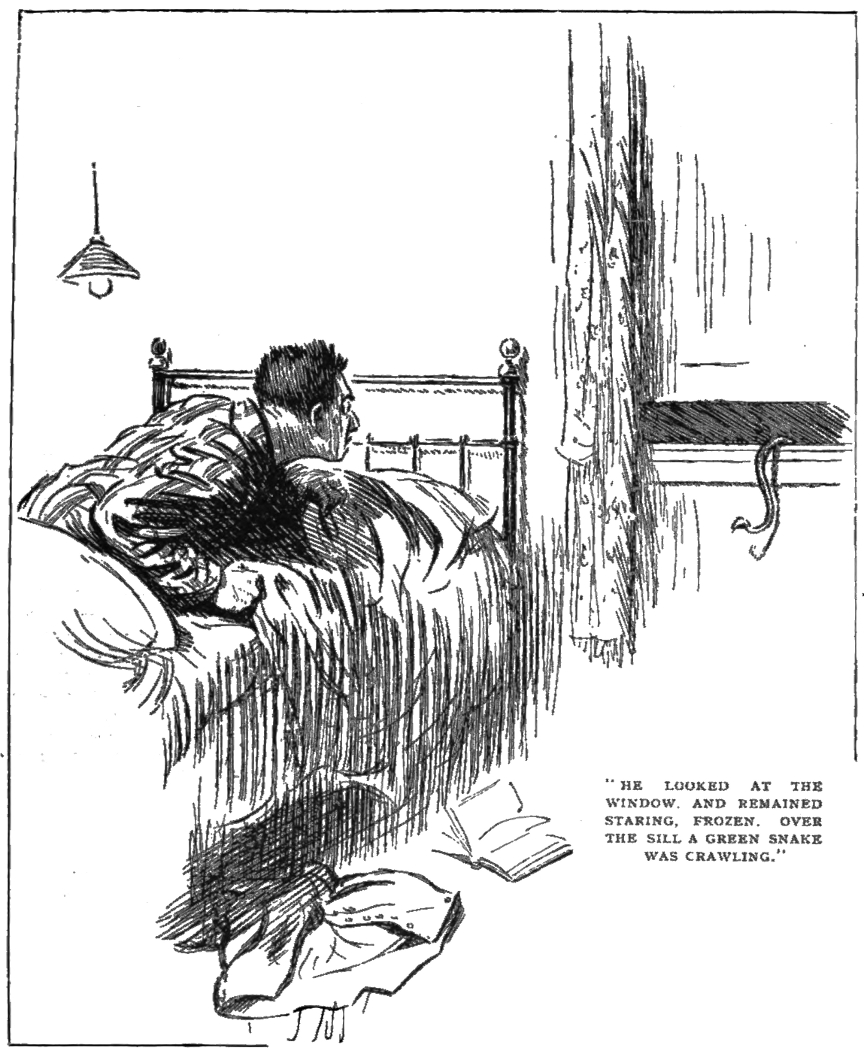

His heart gave a bound. There it was again, that hissing sound. And this time he was sure it came from the window.

He looked at the window, and remained staring, frozen. Over the sill, with a graceful, leisurely movement, a green snake was crawling. As it crawled, it raised its head and peered from side to side, like a shortsighted man looking for his spectacles. It hesitated a moment on the edge of the sill, then wriggled to the floor and began to cross the room. Squiffy stared on.

It would have pained Peter deeply, for he was a snake of great sensibility, if he had known how much his entrance had disturbed the occupant of the room. He himself had no feeling but gratitude for the man who had opened the window and so enabled him to get in out of the rather nippy night air. Ever since the bag had swung open and shot him out on to the sill of the window below Archie’s, he had been waiting patiently for something of the kind to happen. He was a snake who took things as they came, and was prepared to rough it a bit if necessary; but for the last hour or two he had been hoping that somebody would do something practical in the way of getting him in out of the cold. When at home, he had an eiderdown quilt to sleep on, and the stone of the window-sill was a little trying to a snake of regular habits. He crawled thankfully across the floor under Squiffy’s bed. There was a pair of trousers there, for his host had undressed when not in a frame of mind to fold his clothes neatly and place them upon a chair. Peter looked the trousers over. They were not an eiderdown quilt, but they would serve. He curled up in them and went to sleep. He had had an exciting day, and was glad to turn in.

After about ten minutes, the tension of Squiffy’s attitude relaxed. His heart, which had seemed to suspend its operations, began beating again. Reason re-asserted itself. He peeped cautiously under the bed. He could see nothing.

Squiffy was convinced. He told himself that he had never really believed in Peter as a living thing. It stood to reason that there couldn’t really be a snake in his room. The window looked out on emptiness. His room was several stories above the ground, There was a stern, set expression on Squiffy’s face as he climbed out of bed. It was the expression of a man who is turning over a new leaf, starting a new life. He looked about the room for some implement which would carry out the deed he had to do, and finally pulled out one of the curtain-rods. Using this as a lever, he broke open the topmost of the six cases which stood in the corner. The soft wood cracked and split. Squiffy drew out a straw-covered bottle. For a moment he stood looking at it, as a man might gaze at a friend on the point of death. Then, with a sudden determination, he went into the bathroom. There was a crash of glass and a gurgling sound.

Half an hour later the telephone in Archie’s room rang.

“I say, Archie, old top,” said the voice of Squiffy.

“Halloa, old bean! Is that you?”

“I say, could you pop down here for a second? I’m rather upset.”

“Absolutely! Which room?”

“Four-forty-one.”

“I’ll be with you eftsoones or right speedily.”

“Thanks, old man.”

“What appears to be the difficulty?”

“Well, as a matter of fact, I thought I saw a snake!”

“A snake!”

“I’ll tell you all about it when you come down.”

Archie found Lord Seacliff seated on his bed. An arresting aroma of mixed drinks pervaded the atmosphere.

“I say! What?” said Archie, inhaling.

“That’s all right. I’ve been pouring my stock away. Just finished the last bottle.”

“But why?”

“I told you. I thought I saw a snake!”

“Green?”

Squiffy shivered slightly.

“Frightfully green!”

Archie hesitated. He perceived that there are moments when silence is the best policy. He had been worrying himself over the unfortunate case of his friend, and now that Fate seemed to have provided a solution, it would be rash to interfere merely to ease the old bean’s mind. If Squiffy was going to reform because he thought he had seen an imaginary snake, better not to let him know that the snake was a real one.

“Dashed serious!” he said.

“Bally dashed serious!” agreed Squiffy. “I’m going to cut it out!”

“Great scheme!”

“You don’t think,” asked Squiffy, with a touch of hopefulness, “that it could have been a real snake?”

“Never heard of the management supplying them.”

“I thought it went under the bed.”

“Well, take a look.”

Squiffy shuddered.

“Not me! I say, old top, you know, I simply can’t sleep in this room now. I was wondering if you could give me a doss somewhere in yours.”

“Rather! I’m in five-forty-one. Just above. Trot along up. Here’s the key. I’ll tidy up a bit here, and join you in a minute.”

Squiffy put on a dressing-gown and disappeared. Archie looked under the bed. From the trousers the head of Peter popped up with its usual expression of amiable inquiry. Archie nodded pleasantly, and sat down on the bed. The problem of his little friend’s immediate future wanted thinking over.

He lit a cigarette and remained for a while in thought. Then he rose. An admirable solution had presented itself. He picked Peter up and placed him in the pocket of his dressing-gown. Then, leaving the room, he mounted the stairs till he reached the seventh floor. Outside a room halfway down the corridor he paused.

From within, through the open transom, came the rhythmical snoring of a good man taking his rest after the labours of the day. Mr. Brewster was always a heavy sleeper.

“There’s always a way,” thought Archie, philosophically, “if a chappie only thinks of it.”

His father-in-law’s snoring took on a deeper note. Archie extracted Peter from his pocket and dropped him gently through the transom.

Next month: “Doing Father a Bit of Good.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums