The Strand Magazine, March 1930

ASK anyone at the Drones, and they will tell you that Bertram Wooster is a fellow whom it is dashed difficult to deceive. Old Lynx-Eye is about what it amounts to. I observe and deduce. I weigh the evidence and draw my conclusions. And that is why Uncle George had not been in my midst more than about two minutes before I, so to speak, saw all. To my trained eye the thing stuck out a mile.

And yet it seemed so dashed absurd. Consider the facts, if you know what I mean.

I mean to say, for years, right back to the time when I first went to Eton, this bulging relative had been one of the recognized eyesores of London. He was fat then, and day by day in every way has been getting fatter ever since, till now tailors measure him just for the sake of the exercise. He is what they call a prominent London clubman—one of those birds in tight morning coats and grey toppers whom you see toddling along St. James’s Street on fine afternoons, puffing a bit as they make the grade. Slip a ferret into any good club between Piccadilly and Pall Mall, and you would start half-a-dozen Uncle Georges.

He spends his time lunching and dining at the Buffers and, between meals, sucking down spots in the smoking-room and talking to anyone who will listen about the lining of his stomach. About twice a year his liver lodges a formal protest and he goes off to Harrogate or Carlsbad to get planed down. Then back again and on with the programme. The last bloke in the world, in short, who you would think would ever fall a victim to the divine pash. And yet, if you will believe me, that was absolutely the strength of it.

This old pestilence blew in on me one morning at about the hour of the after-breakfast cigarette.

“Oh, Bertie,” he said.

“Hullo?”

“You know those ties you’ve been wearing. Where did you get them?”

“Blucher’s, in the Burlington Arcade.”

“Thanks.”

He walked across to the mirror and stood in front of it, gazing at himself in an earnest manner.

“Smut on your nose?” I asked, courteously.

Then I suddenly perceived that he was wearing a sort of horrible simper, and I confess it chilled the blood to no little extent. Uncle George, with face in repose, is hard enough on the eye. Simpering, he goes right above the odds.

“Ha!” he said.

He heaved a long sigh, and turned away. Not too soon, for the mirror was on the point of cracking.

“I’m not so old,” he said, in a musing sort of voice.

“So old as what?”

“Properly considered, I’m in my prime. Besides, what a young and inexperienced girl needs is a man of weight and years to lean on. The sturdy oak, not the sapling.”

It was at this point that, as I said above, I saw all.

“Great Scott, Uncle George!” I said. “You aren’t thinking of getting married?”

“Who isn’t?” he said.

“You aren’t,” I said.

“Yes, I am. Why not?”

“Oh, well——”

“Marriage is an honourable state.”

“Oh, absolutely.”

“It might make you a better man, Bertie.”

“Who says so?”

“I say so. Marriage might turn you from a frivolous young scallywag into—er—a non-scallywag. Yes, confound you, I am thinking of getting married, and if Agatha comes sticking her oar in I’ll—I’ll—well, I shall know what to do about it.”

He exited on the big line, and I rang the bell for Jeeves. The situation seemed to me one that called for a cosy talk.

“ JEEVES,” I said.

“Sir?”

“You know my Uncle George?”

“Yes, sir. His lordship has been familiar to me for some years.”

“I don’t mean do you know my Uncle George. I mean do you know what my Uncle George is thinking of doing?”

“Contracting a matrimonial alliance, sir.”

“Good Lord! Did he tell you?”

“No, sir. Oddly enough, I chance to be acquainted with the other party in the matter.”

“The girl?”

“The young person, yes, sir. It was from her aunt, with whom she resides, that I received the information that his lordship was contemplating matrimony.”

“Who is she?

“A Miss Platt, sir. Miss Rhoda Platt, of Wistaria Lodge, Kitchener Road, East Dulwich.”

“Young?”

“Yes, sir.”

“The old fathead.”

“Yes, sir. The expression is one which I would, of course, not have ventured to employ myself, but I confess to thinking his lordship somewhat ill-advised. One must remember, however, that it is not unusual to find gentlemen of a certain age yielding to what might be described as a sentimental urge. They appear to experience what I may term a sort of Indian Summer, a kind of temporarily renewed youth. The phenomenon is particularly noticeable, I am given to understand, in the United States of America among the wealthier inhabitants of the city of Pittsburg. It is notorious, I am told, that sooner or later, unless restrained, they always endeavour to marry chorus girls. Why this should be so, I am at a loss to say, but——”

I saw that this was going to take some time. I tuned out.

“From something in Uncle George’s manner, Jeeves, as he referred to my Aunt Agatha’s probable reception of the news, I gather that this Miss Platt is not of the noblesse.”

“No, sir. She is a waitress at his lordship’s club.”

“My God! The proletariat!”

“The lower middle classes, sir.”

“Well, yes, by stretching it a bit, perhaps. Still, you know what I mean.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Rummy thing, Jeeves,” I said thoughtfully, “this modern tendency to marry waitresses. If you remember, before he settled down, young Bingo Little was repeatedly trying to do it.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Odd!”

“Yes, sir.”

“Still, there it is, of course. The point to be considered now is, what will Aunt Agatha do about this? You know her, Jeeves. She is not like me. I’m broad-minded. If Uncle George wants to marry waitresses, let him, say I. I hold that the rank is but the penny stamp——”

“Guinea stamp, sir.”

“All right, guinea stamp. Though I don’t believe there is such a thing. I shouldn’t have thought they came higher than five bob. Well, as I was saying, I maintain that the rank is but the guinea stamp and a girl’s a girl for all that.”

“ ‘For a’ that,’ sir. The poet Burns wrote in the North British dialect.”

“Well, ‘a’ that,’ then, if you prefer it.”

“I have no preference in the matter, sir. It is simply that the poet Burns——”

“Never mind about the poet Burns.”

“No, sir.”

“Forget the poet Burns.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Expunge the poet Burns from your mind.”

“I will do so immediately, sir.”

“What we have to consider is not the poet Burns but the Aunt Agatha. She will kick, Jeeves.”

“Very probably, sir.”

“And, what’s worse, she will lug me into the mess. There is only one thing to be done; pack the toothbrush and let us escape while we may, leaving no address.”

“Very good, sir.”

At this moment the bell rang.

“Ha!” I said. “Someone at the door.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Probably Uncle George back again. I’ll answer it. You go and get ahead with the packing.”

“Very good, sir.”

I sauntered along the passage, whistling carelessly, and there on the mat was Aunt Agatha. Herself. Not a picture.

A nasty jar.

“Oh, hullo!” I said, it seeming but little good to tell her I was out of town and not expected back for some weeks.

“I wish to speak to you, Bertie,” said the Family Curse. “I am greatly upset.”

She legged it into the sitting-room and volplaned into a chair. I followed, thinking wistfully of Jeeves packing in the bedroom. That suit-case would not be needed now. I knew what she must have come about.

“I’ve just seen Uncle George,” I said, giving her a lead.

“So have I,” said Aunt Agatha, shivering in a marked manner. “He called on me while I was still in bed to inform me of his intention of marrying some impossible girl from South Norwood.”

“East Dulwich, the cognoscenti inform me.”

“Well, East Dulwich, then. It is the same thing. But who told you?”

“Jeeves.”

“And how, pray, does Jeeves come to know all about it?”

“There are very few things in this world, Aunt Agatha,” I said gravely, “that Jeeves doesn’t know all about. He’s met the girl.”

“Who is she?”

“One of the waitresses at the Buffers.”

I had expected this to register, and it did. The relative let out a screech rather like the Cornish Express going through a junction.

“I take it from your manner, Aunt Agatha,” I said, “that you want this thing stopped.”

“Of course it must be stopped.”

“Then there is but one policy to pursue. Let me ring for Jeeves and ask his advice.”

Aunt Agatha stiffened visibly. Very much the grande dame of the old régime.

“Are you seriously suggesting that we should discuss this intimate family matter with your manservant?”

“Absolutely. Jeeves will find the way.”

“I have always known that you were an imbecile, Bertie,” said the flesh and blood, now down at about three degrees Fahrenheit, “but I did suppose that you had some proper feeling, some pride, some respect for your position.”

“Well, you know what the poet Burns says.”

She squelched me with a glance.

“Obviously the only thing to do,” she said, “is to offer this girl money.”

“Money?”

“Certainly. It will not be the first time your uncle has made such a course necessary.”

WE sat for a bit, brooding. The family always sits brooding when the subject of Uncle George’s early romance comes up. I was too young to be actually in on it at the time, but I’ve had the details frequently from many sources, including Uncle George. Let him get even the slightest bit pickled, and he will tell you the whole story, sometimes twice in an evening. It was a barmaid at the Criterion, just before he came into the title. Her name was Maudie, and he loved her dearly, but the family would have none of it. They dug down into the sock and paid her off. Just one of those human-interest stories, if you know what I mean.

I wasn’t so sold on this money-offering scheme.

“Well, just as you like, of course,” I said, “but you’re taking an awful chance. I mean, whenever people do it in novels and plays, they always get the dickens of a welt. The girl gets the sympathy of the audience every time. She just draws herself up and looks at them with clear, steady eyes, causing them to feel not a little cheesey. If I were you, I would sit tight and let Nature take its course.”

“I don’t understand you.”

“Well, consider for a moment what Uncle George looks like. No Greta Garbo, believe me. I should simply let the girl go on looking at him. Take it from me, Aunt Agatha, I’ve studied human nature and I don’t believe there’s a female in the world who could see Uncle George fairly often in those waistcoats he wears without feeling that it was due to her better self to give him the gate. Besides, this girl sees him at meal-times, and Uncle George with his head down among the food-stuffs is a spectacle which——”

“If it is not troubling you too much, Bertie, I should be greatly obliged if you would stop drivelling.”

“Just as you say. All the same, I think you’re going to find it dashed embarrassing offering this girl money.”

“I am not proposing to do so. You will undertake the negotiations.”

“Me?”

“Certainly. I should think a hundred pounds would be ample. But I will give you a blank cheque, and you are at liberty to fill it in for a higher sum, if it becomes necessary. The essential point is that, cost what it may, your uncle must be released from this entanglement.”

“So you’re going to shove this off on me?”

“It is quite time you did something for the family.”

“And when she draws herself up and looks at me with clear, steady eyes, what do I do for an encore?”

“There is no need to discuss the matter any further. You can get down to East Dulwich in half an hour. There is a frequent service of trains. I will remain here to await your report.”

“But listen!”

“Bertie, you will go and see this woman immediately.”

“Yes, but dash it!”

“Bertie!”

I threw in the towel.

“Oh, right ho, if you say so.”

“I do say so.”

“Oh, well, in that case, right ho.”

I DON’T know if you have ever tooled off to East Dulwich to offer a strange female a hundred smackers to release your Uncle George. In case you haven’t, I may tell you that there are plenty of things that are lots better fun. I didn’t feel any too good driving to the station. I didn’t feel any too good in the train. And I didn’t feel any too good as I walked to Kitchener Road. But the moment when I felt least good was when I had actually pressed the front-door bell and a rather grubby-looking maid had let me in and shown me down a passage and into a room with pink paper on the walls, a piano in the corner, and a lot of photographs on the mantelpiece.

Barring a dentist’s waiting-room, which it rather resembles, there isn’t anything that quells the spirit much more than one of these suburban parlours. They are extremely apt to have stuffed birds in glass cases standing about on small tables, and if there is one thing which gives the man of sensibility that sinking feeling it is the cold, accusing eye of a ptarmigan or whatever it may be that has had its interior organs removed and sawdust substituted.

There were three of these cases in the parlour of Wistaria Lodge, so that, wherever you looked, you were sure to connect. Two were singletons, the third a family group, consisting of a father bullfinch, a mother bullfinch, and little Master Bullfinch, the last named of whom wore an expression that was definitely that of a thug, and did more to damp my joie de vivre than all the rest of them put together.

I had moved to the window and was examining the aspidistra in order to avoid this creature’s gaze, when I heard the door open and, turning, found myself confronted by something which, since it could hardly be the girl, I took to be the aunt.

“Oh, good morning,” I said.

The words came out rather roopily, for I was feeling a bit on the stunned side. I mean to say, the room being so small and this exhibit so large, I had got that feeling of wanting air. There are some people who don’t seem to be intended to be seen close to, and this aunt was one of them. Billowy curves, if you know what I mean. I should think that in her day she must have been a very handsome girl, though even then on the substantial side. By the time she came into my life, she had taken on a good deal of excess weight. She looked like a photograph of an opera singer of the ’eighties. Also the orange hair and the magenta dress.

However, she was a friendly soul. She seemed glad to see Bertram. She smiled broadly.

“So here you are at last!” she said.

I couldn’t make anything of this.

“Eh?”

“But I don’t think you had better see my niece just yet. She’s just having a nap.”

“Oh, in that case——”

“Seems a pity to wake her, doesn’t it?”

“Oh, absolutely,” I said, relieved.

“When you get the influenza, you don’t sleep at night, and then if you doze off in the morning, well, it seems a pity to wake someone, doesn’t it?”

“Miss Platt has influenza?”

“That’s what we think it is. But, of course, you’ll be able to say. But we needn’t waste time. Since you’re here, you can be taking a look at my knee.”

“Your knee?”

I am all for knees at their proper time and, as you might say, in their proper place, but somehow this didn’t seem the moment. However, she carried on according to plan.

“What do you think of that knee?” she asked, lifting the seven veils.

Well, of course, one has to be polite.

“Terrific!” I said.

“You wouldn’t believe how it hurts me sometimes.”

“Really?”

“A sort of shooting pain. It just comes and goes. And I’ll tell you a funny thing.”

“What’s that?” I said, feeling I could do with a good laugh.

“Lately I’ve been having the same pain just here, at the end of the spine.”

“You don’t mean it!”

“I do. Like red-hot needles. I wish you’d have a look at it.”

“At your spine?”

“Yes.”

I shook my head. Nobody is fonder of a bit of fun than myself, and I am all for Bohemian camaraderie and making a party go, and all that. But there is a line, and we Woosters know when to draw it.

“It can’t be done,” I said, austerely. “Not spines. Knees, yes. Spines, no,” I said.

She seemed surprised.

“Well,” she said, “you’re a funny sort of doctor, I must say.”

I’m pretty quick, as I said before, and I began to see that something in the nature of a misunderstanding must have arisen.

“Doctor?”

“Well, you call yourself a doctor, don’t you?”

“Did you think I was a doctor?”

“Aren’t you a doctor?”

“No. Not a doctor.”

We had got it straightened out. The scales had fallen from our eyes. We knew where we were.

I had suspected that she was a genial soul. She now endorsed this view. I don’t think I have ever heard a woman laugh so heartily.

“Well, that’s the best thing!” she said, borrowing my handkerchief to wipe her eyes. “Did you ever! But, if you aren’t the doctor, who are you?”

“Wooster’s the name. I came to see Miss Platt.”

“What about?”

THIS was the moment, of course, when I should have come out with the cheque and sprung the big effort. But somehow I couldn’t make it. You know how it is. Offering people money to release your uncle is a scaly enough job at best, and when the atmosphere’s not right the shot simply isn’t on the board.

“Oh, just came to see her, you know.” I had rather a bright idea. “My uncle heard she was seedy, don’t you know, and asked me to look in and make inquiries,” I said.

“Your uncle?”

“Lord Yaxley.”

“Oh! So you are Lord Yaxley’s nephew?”

“That’s right. I suppose he’s always popping in and out here, what?”

“No. I’ve never met him.”

“You haven’t?”

“No. Rhoda talks a lot about him, of course, but for some reason she’s never so much as asked him to look in for a cup of tea.”

I began to see that this Rhoda knew her business. If I’d been a girl with someone wanting to marry me and knew that there was an exhibit like this aunt hanging around the home, I, too, should have thought twice about inviting him to call until the ceremony was over and he had actually signed on the dotted line. I mean to say, a thoroughly good soul—heart of gold beyond a doubt—but not the sort of thing you wanted to spring on Romeo before the time was ripe.

“I suppose you were all very surprised when you heard about it?” she said.

“Surprised is right.”

“Of course, nothing is definitely settled yet.”

“You don’t mean that? I thought——”

“Oh, no. She’s thinking it over.”

“I see.”

“Of course, she feels it’s a great compliment. But then sometimes she wonders if he isn’t too old.”

“My Aunt Agatha has rather the same idea.”

“Of course, a title is a title.”

“Yes, there’s that. What do you think about it yourself?”

“Oh, it doesn’t matter what I think. There’s no doing anything with girls these days, is there?”

“Not much.”

“What I often say is, I wonder what girls are coming to. Still, there it is.”

“Absolutely.”

There didn’t seem much reason why the conversation shouldn’t go on for ever. She had the air of a woman who has settled down for the day. But at this point the maid came in and said the doctor had arrived.

I got up.

“I’ll be tooling off, then.”

“If you must.”

“I think I’d better.”

“Well, pip, pip!”

“Toodle-oo!” I said, and out into the fresh air.

Knowing what was waiting for me at home, I would have preferred to have gone to the club and spent the rest of the day there. But the thing had to be faced.

“Well?” said Aunt Agatha, as I trickled into the sitting-room.

“Well, yes and no,” I replied.

“What do you mean? Did she refuse the money?”

“Not exactly.”

“She accepted it?”

“Well, there again not precisely.”

I explained what had happened. I wasn’t expecting her to be any too frightfully pleased, and it’s as well that I wasn’t, because she wasn’t. In fact, as the story unfolded, her comments became fruitier and fruitier, and when I had finished she uttered an exclamation that nearly broke a window. It sounded something like “Gor!” as if she had started to say “Gorblimey!” and had remembered her ancient lineage just in time.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “And can a man say more? I lost my nerve. The old morale suddenly turned blue on me. It’s the sort of thing that might have happened to anyone.”

“I never heard of anything so spineless in my life!”

I shivered, like a warrior whose old wound hurts him.

“I’d be most awfully obliged, Aunt Agatha,” I said, “if you would not use that word spine. It awakens memories.”

The door opened. Jeeves appeared.

“Sir?”

“Yes, Jeeves?”

“I thought you called, sir.”

“No, Jeeves.”

“Very good, sir.”

There are moments when, even under the eye of Aunt Agatha, I can take the firm line. And now, seeing Jeeves standing there with the light of intelligence simply fizzing in every feature, I suddenly felt how perfectly footling it was to give this pre-eminent source of balm and comfort the go-by simply because Aunt Agatha had prejudices against discussing family affairs with the staff. It might make her say “Gor!” again, but I decided to do as we ought to have done right from the start—put the case in his hands.

“Jeeves,” I said, “this matter of Uncle George.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You know the circs.”

“Yes sir.”

“You know what we want.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then advise us. And make it snappy. Think on your feet.”

I heard Aunt Agatha rumble like a volcano just before it starts to set about the neighbours, but I did not wilt. I had seen the sparkle in Jeeves’s eye which indicated that an idea was on the way.

“I understand that you have been visiting the young person’s home, sir?”

“Just got back.”

“Then you no doubt encountered the young person’s aunt?”

“Jeeves, I encountered nothing else but.”

“Then the suggestion which I am about to make will, I feel sure, appeal to you, sir. I would recommend that you confronted his lordship with this woman. It has always been her intention to continue residing with her niece after the latter’s marriage. Should he meet her, this reflection might give his lordship pause. As you are aware, sir, she is a kind-hearted woman, but definitely of the people.”

“Jeeves, you are right! Apart from anything else, that orange hair!”

“Exactly, sir.”

“Not to mention the magenta dress.”

“Precisely, sir.”

“I’ll ask her to lunch to-morrow, to meet him. You see,” I said to Aunt Agatha, who was still fermenting in the background, “a ripe suggestion first crack out of the box. Did I or did I not tell you——”

“That will do, Jeeves,” said Aunt Agatha.

“Very good, madam.”

For some minutes after he had gone Aunt Agatha strayed from the point a bit, confining her remarks to what she thought of a Wooster who could lower the prestige of the clan by allowing menials to get above themselves. Then she returned to what you might call the main issue.

“Bertie,” she said, “you will go and see this girl again to-morrow, and this time you will do as I told you.”

“But, dash it! With this excellent alternative scheme, based firmly on the psychology of the individual——”

“That is quite enough, Bertie. You heard what I said. I am going. Good-bye.”

She buzzed off, little knowing of what stuff Bertram Wooster was made. The door had hardly closed before I was shouting for Jeeves.

“Jeeves,” I said, “the recent aunt will have none of your excellent alternative scheme, but, none the less, I propose to go through with it unswervingly. I consider it a ball of fire. Can you get hold of this female and bring her here for lunch tomorrow?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good. Meanwhile, I will be ’phoning Uncle George. We will do Aunt Agatha good despite herself. What is it the poet says, Jeeves?”

“The poet Burns, sir?”

“Not the poet Burns. Some other poet. About doing good by stealth.”

“These little acts of unremembered kindness, sir?”

“That’s it in a nutshell, Jeeves.”

I SUPPOSE doing good by stealth ought to give one a glow, but I can’t say I found myself exactly looking forward to the binge in prospect. Uncle George by himself is a mouldy enough luncheon companion, being extremely apt to collar the conversation and confine it to a description of his symptoms, he being one of those birds who can never be brought to believe that the general public isn’t agog to hear about the lining of his stomach. Add the aunt, and you have a little gathering which might well dismay the stoutest. The moment I woke I felt conscious of some impending doom, and the cloud, if you know what I mean, grew darker all the morning. By the time Jeeves came in with the cocktails, I was feeling pretty low.

“For two pins, Jeeves,” I said, “I would turn the whole thing up and leg it to the Drones.”

“I can readily imagine that this will prove something of an ordeal, sir.”

“How did you get to know these people, Jeeves?”

“It was through a young fellow of my acquaintance, sir. Colonel Mainwaring-Smith’s personal gentleman’s gentleman. He and the young person had an understanding at the time, and he desired me to accompany him to Wistaria Lodge and meet her.”

“They were engaged?”

“Not precisely engaged, sir. An understanding.”

“What did they quarrel about?”

“They did not quarrel, sir. When his lordship began to pay his addresses, the young person, naturally flattered, began to waver between love and ambition. But even now she has not formally rescinded the understanding.”

“Then if your scheme works and Uncle George edges out, it will do your pal a bit of good?”

“Yes, sir. Smethurst—his name is Smethurst—would consider it a consummation devoutly to be wished.”

An unseen hand without tootled on the bell, and I braced myself to play the host. The binge was on.

“Mrs. Wilberforce, sir,” announced Jeeves.

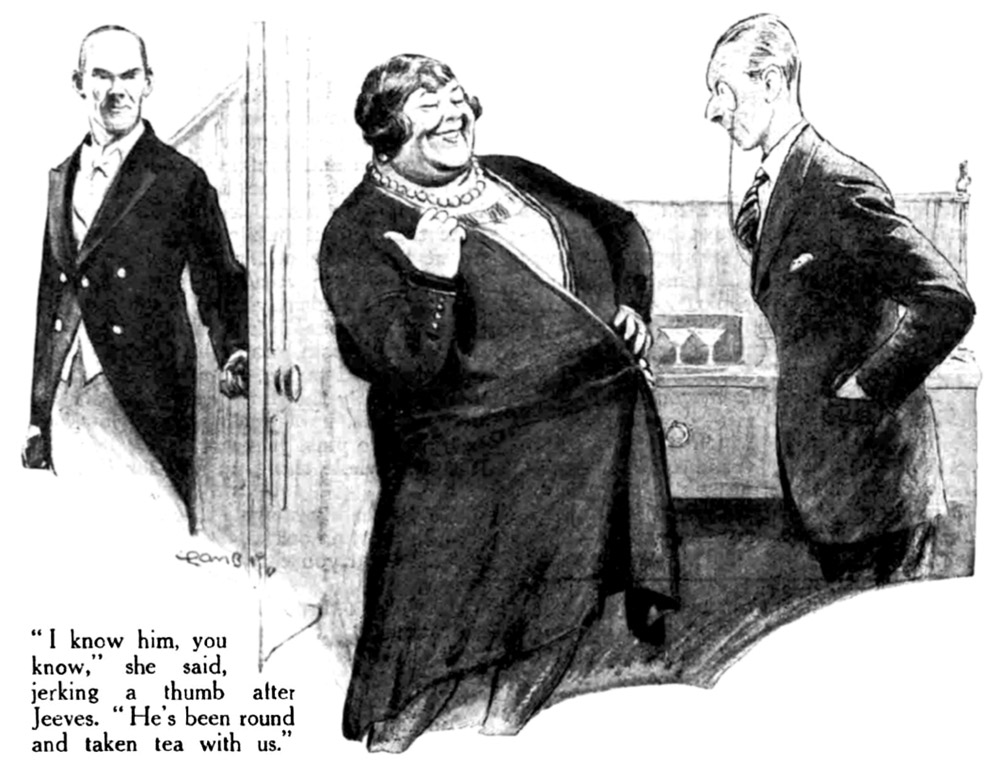

“And how I’m to keep a straight face with you standing behind my chair and saying, ‘Madam, can I tempt you with a potato?’ is more than I know,” said the aunt, sailing in, looking larger and pinker and matier than ever. “I know him, you know,” she said, jerking a thumb after Jeeves. “He’s been round and taken tea with us.”

“So he told me.”

She gave the sitting-room the once-over.

“You’ve got a nice place here,” she said, “though I like more pink about. It’s so cheerful. What’s that you’ve got there? Cocktails?”

“Martini with a spot of absinthe,” I said, beginning to pour.

She gave a girlish squeal.

“Don’t you try to make me drink that stuff! Do you know what would happen if I touched one of those things? I’d be racked with pain. What they do to the lining of your stomach!”

“Oh, I don’t know.”

“I do. If you had been a barmaid as long as I was, you’d know, too.”

“Oh—er—were you a barmaid?”

“For years, when I was younger than I am. At the Criterion.”

I dropped the shaker.

“There!” she said, pointing the moral. “That’s through drinking that stuff. Makes your hand wobble. What I always used to say to the boys was, ‘Port, if you like. Port’s wholesome. I appreciate a drop of port myself. But these new-fangled messes from America, no.’ But they would never listen to me.”

I was eyeing her warily. Of course, there must have been thousands of barmaids at the Criterion in its time, but still, it gave one a bit of a start. It was years ago that Uncle George’s dash at a mésalliance had occurred—long before he came into the title—but the Wooster clan still quivered at the name of the Criterion.

“Er—when you were at the Cri.,” I said, “did you ever happen to run into a fellow of my name?”

“I’ve forgotten what it is. I’m always silly about names.”

“Wooster.”

“Wooster! When you were there yesterday I thought you said Foster. Wooster! Did I run into a fellow named Wooster? Well! Why, George Wooster and me—Piggy, I used to call him—were going off to the registrar’s, only his family heard of it and interfered. They offered me a lot of money to give him up, and, like a silly girl, I let them persuade me. If I’ve wondered once what became of him, I’ve wondered a thousand times. Is he a relation of yours?”

“Excuse me,” I said, “I just want a word with Jeeves.” I legged it for the pantry.

“ JEEVES!”

“Sir?”

“Do you know what’s happened?”

“No, sir.”

“This female——”

“Sir?”

“She’s Uncle George’s barmaid!”

“Sir?”

“Oh, dash it, you must have heard of Uncle George’s barmaid. You know all the family history. The barmaid he wanted to marry years ago.”

“Ah, yes, sir.”

“She’s the only woman he ever loved. He’s told me so a million times. Every time he gets to the second liqueur, he always becomes maudlin about this female. What a dashed bit of bad luck! The first thing we know, the call of the past will be echoing in his heart. I can feel it, Jeeves. She’s just his sort. The first thing she did when she came in was to start talking about the lining of her stomach. You see the hideous significance of that, Jeeves? The lining of his stomach is Uncle George’s favourite topic of conversation. It means that he and she are kindred souls. This woman and he will be like——”

“Deep calling to deep, sir?”

“Exactly.”

“Most disturbing, sir.”

“What’s to be done?”

“I could not say, sir.”

“I’ll tell you what I’m going to do—’phone him and say the lunch is off.”

“Scarcely feasible, sir. I fancy that is his lordship at the door now.”

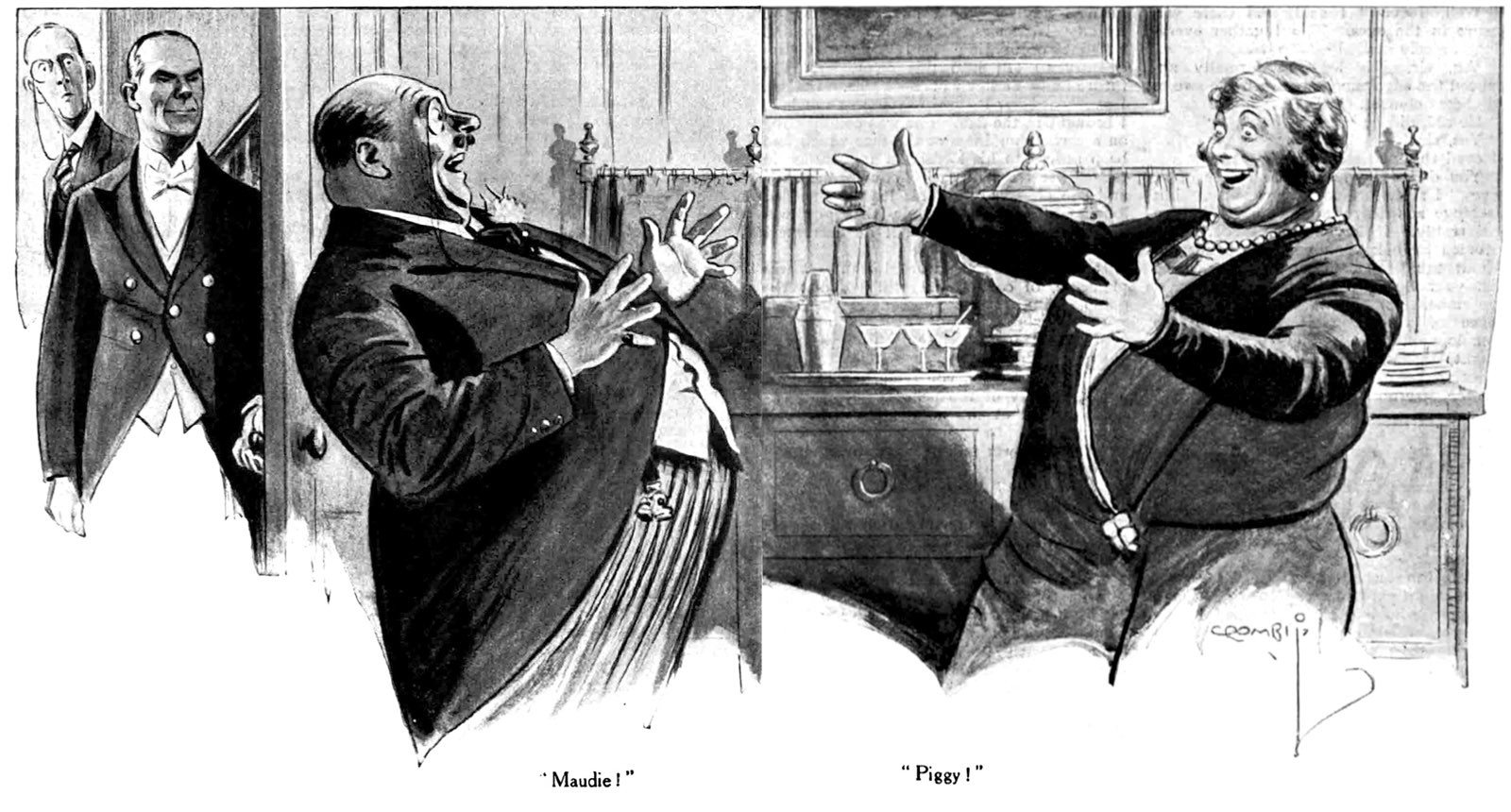

And so it was. Jeeves let him in, and I followed him as he navigated down the passage to the sitting-room. There was a stunned silence as he went in, and then a couple of the startled yelps you hear when old buddies get together after long separation.

“Piggy!”

“Maudie!”

“Well, I never!”

“Well, I’m dashed!”

“Did you ever!”

“Well, bless my soul!”

“Fancy you being Lord Yaxley!”

“Came into the title soon after we parted.”

“Just to think!”

“You could have knocked me down with a feather!”

I hung about in the offing, now on this leg, now on that. For all the notice they took of me, I might just have well been the late Bertram Wooster, disembodied.

“Maudie, you don’t look a day older, dash it!”

“Nor do you, Piggy.”

“How have you been all these years?”

“Pretty well. The lining of my stomach isn’t all it should be.”

“Good Gad! You don’t say so? I have trouble with the lining of my stomach.”

“It’s a sort of heavy feeling after meals.”

“I get a sort of heavy feeling after meals. What are you trying for it?”

“I’ve been taking Perkins’s Digestine.”

“My dear girl, no use! No use at all. Tried it myself for years, and got no relief. Now, if you really want something that is some good——”

I slid away. The last I saw of them, Uncle George was down beside her on the Chesterfield, buzzing hard.

“Jeeves,” I said, tottering into the pantry.

“Sir?”

“There will only be two for lunch. Count me out. If they notice I’m not there, tell them I was called away by an urgent ’phone message. The situation has got beyond Bertram, Jeeves. You will find me at the Drones.”

“Very good, sir.”

It was lateish in the evening when one of the waiters came to me as I played a distrait game of snooker pool and informed me that Aunt Agatha was on the ’phone.

“Bertie!”

“Hullo?”

I was amazed to note that her voice was like that of an aunt who feels that things are breaking right. It had the birdlike trill.

“Bertie, have you that cheque I gave you?”

“Yes.”

“Then tear it up. It will not be needed.”

“Eh?”

“I say it will not be needed. Your uncle has been speaking to me on the telephone. He is not going to marry that girl.”

“Not?”

“No. Apparently he has been thinking it over and sees how unsuitable it would have been. But what is astonishing is that he is going to be married!”

“He is?”

“Yes, to an old friend of his, a Mrs. Wilberforce. A woman of a sensible age, he gave me to understand. I wonder which Wilberforces that would be. There are two main branches of the family—the Essex Wilberforces and the Cumberland Wilberforces. I believe there is also a cadet branch somewhere in Shropshire.”

“And one in East Dulwich,” I said.

“What did you say?”

“Nothing,” I said. “Nothing.”

I hung up. Then back to the old flat, feeling a trifle sand-bagged.

“Well, Jeeves,” I said, and there was censure in the eyes. “So I gather everything is nicely settled?”

“Yes, sir. His lordship formally announced the engagement between the sweets and cheese courses, sir.”

“He did, did he?”

“Yes, sir.”

I eyed the man sternly.

“You do not appear to be aware of it, Jeeves,” I said, in a cold, level voice, “but this binge has depreciated your stock very considerably. I have always been accustomed to look upon you as a counsellor without equal. I have, so to speak, hung upon your lips. And now see what you have done. All this is the direct consequence of your scheme, based on the psychology of the individual. I should have thought, Jeeves, that, knowing the woman—meeting her socially, as you might say, over the afternoon cup of tea—you might have ascertained that she was Uncle George’s barmaid.”

“I did, sir.”

“What!”

“I was aware of the fact, sir.”

“Then you must have known what would happen if she came to lunch and met him.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, I’m dashed!”

“If I might explain, sir. The young man Smethurst, who is greatly attached to the young person, is an intimate friend of mine. He applied to me some little while back in the hope that I might be able to do something to ensure that the young person followed the dictates of her heart and refrained from permitting herself to be lured by gold and the glamour of his lordship’s position. There will now be no obstacle to their union.”

“I see. Little acts of unremembered kindness, what?”

“Precisely, sir.”

“And how about Uncle George? You’ve landed him pretty nicely in the cart.”

“No, sir, if I may take the liberty of opposing your view. I fancy that Mrs. Wilberforce should make an ideal mate for his lordship. If there was a defect in his lordship’s mode of life, it was that he was a little unduly attached to the pleasures of the table——”

“Ate like a pig, you mean?”

“I would not have ventured to put it in quite that way, sir, but the expression does meet the facts of the case. He was also inclined to drink rather more than his medical adviser would have approved of. Elderly bachelors who are wealthy and without occupation tend somewhat frequently to fall into this error, sir. The future Lady Yaxley will check this. Indeed, I overheard her ladyship saying as much as I brought in the fish. She was commenting on a certain puffiness of the face which had been absent in his lordship’s appearance in the earlier days of their acquaintanceship, and she observed that his lordship needed looking after. I fancy, sir, that you will find the union will turn out an extremely satisfactory one.”

It was—what’s the word I want—it was plausible, of course, but still I shook the onion.

“BUT, Jeeves!”

“Sir?”

“She is, as you remarked not long ago, definitely of the people.”

He looked at me in a reproachful sort of way.

“Sturdy lower middle class stock, sir.”

“H’m!”

“Sir?”

“I said ‘H’m!’ Jeeves.”

“Besides, sir, remember what the poet Tennyson said. Kind hearts are more than coronets.”

“And which of us is going to tell Aunt Agatha that?”

“If I might make the suggestion, sir, I would advise that we omitted to communicate with Mrs. Spencer Gregson in any way. I have your suit-case practically packed. It would be a matter of but a few minutes to bring the car round from the garage——”

“And off over the horizon to where men are men?”

“Precisely, sir.”

“Jeeves,” I said. “I’m not sure that even now I can altogether see eye to eye with you regarding your recent activities. You think you have scattered light and sweetness on every side. I am not so sure. However, with this latest suggestion you have rung the bell. I examine it narrowly and I find no flaw in it. It is the goods. I’ll get the car at once.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Remember what the poet Shakespeare said, Jeeves.”

“What was that, sir?”

“ ‘Exit hurriedly, pursued by a bear.’ You’ll find it in one of his plays. I remember drawing a picture of it on the side of the page, when I was at school.”

Annotations to this story as it appeared in Very Good, Jeeves are on this site.

Compare the American magazine version.

Printer’s errors corrected above:

Magazine, p. 219b, had two places where interrupted speech was shown by a single em dash rather than a two-em dash, after “female” and “will be like”. Corrected for consistency with style in the rest of the story.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums