The Strand Magazine, March 1917

’M

not absolutely certain of my facts, but I rather fancy it’s

Shakespeare—or, if not, it’s some equally brainy lad—who says that

it’s always just when a chappie is feeling particularly top-hole and

more than usually braced with things in general that Fate sneaks up

behind him with the bit of lead piping. There’s no doubt the man’s right.

It’s absolutely that way with me. Take, for instance, the fairly rummy

matter of Lady Malvern and her son Wilmot. A moment before they turned

up I was just thinking how thoroughly all right everything was.

’M

not absolutely certain of my facts, but I rather fancy it’s

Shakespeare—or, if not, it’s some equally brainy lad—who says that

it’s always just when a chappie is feeling particularly top-hole and

more than usually braced with things in general that Fate sneaks up

behind him with the bit of lead piping. There’s no doubt the man’s right.

It’s absolutely that way with me. Take, for instance, the fairly rummy

matter of Lady Malvern and her son Wilmot. A moment before they turned

up I was just thinking how thoroughly all right everything was.

It was one of those topping mornings, and I had just climbed out from under the cold shower, feeling like a two-year-old. As a matter of fact, I was especially bucked just then because the day before I had asserted myself with Jeeves—absolutely asserted myself, don’t you know. You see, the way things had been going on I was rapidly becoming a dashed serf. The man had jolly well oppressed me. I didn’t so much mind when he made me give up one of my new suits, because, Jeeves’s judgment about suits is sound. But I as near as a toucher rebelled when he wouldn’t let me wear a pair of cloth-topped boots which I loved like a couple of brothers. And when he tried to tread on me like a worm in the matter of a hat, I jolly well put my foot down and showed him who was who. It’s a long story, and I haven’t time to tell you now, but the point is that he wanted me to wear the Longacre—as worn by John Drew—when I had set my heart on the Country Gentleman—as worn by another famous actor chappie—and the end of the matter was that, after a rather painful scene, I bought the Country Gentleman. So that’s how things stood on this particular morning, and I was feeling kind of manly and independent.

Well, I was in the bathroom, wondering what there was going to be for breakfast while I massaged the good old spine with a rough towel and sang slightly, when there was a tap at the door. I stopped singing and opened the door an inch.

“What ho without there!”

“Lady Malvern wishes to see you, sir,” said Jeeves.

“Eh?”

“Lady Malvern, sir. She is waiting in the sitting-room.”

“Pull yourself together, Jeeves, my man,” I said, rather severely, for I bar practical jokes before breakfast. “You know perfectly well there’s no one waiting for me in the sitting-room. How could there be when it’s barely ten o’clock yet?”

“I gathered from her ladyship, sir, that she had landed from an ocean liner at an early hour this morning.”

This made the thing a bit more plausible. I remembered that when I had arrived in America about a year before, the proceedings had begun at some ghastly hour like six, and that I had been shot out on to a foreign shore considerably before eight.

“Who the deuce is Lady Malvern, Jeeves?”

“Her ladyship did not confide in me, sir.”

“Is she alone?”

“Her ladyship is accompanied by a Lord Pershore, sir. I fancy that his lordship would be her ladyship’s son.”

“Oh, well, put out rich raiment of sorts, and I’ll be dressing.”

“Our heather-mixture lounge is in readiness, sir.”

“Then lead me to it.”

While I was dressing I kept trying to think who on earth Lady Malvern could be. It wasn’t till I had climbed through the top of my shirt and was reaching out for the studs that I remembered.

“I’ve placed her, Jeeves. She’s a pal of my Aunt Agatha.”

“Indeed, sir?”

“Yes. I met her at lunch one Sunday before I left London. A very vicious specimen. Writes books. She wrote a book on social conditions in India when she came back from the Durbar.”

“Yes, sir? Pardon me, sir, but not that tie!”

“Eh?”

“Not that tie with the heather-mixture lounge, sir!”

It was a shock to me. I thought I had quelled the fellow. It was rather a solemn moment. What I mean is, if I weakened now, all my good work the night before would be thrown away. I braced myself.

“What’s wrong with this tie? I’ve seen you give it a nasty look before. Speak out like a man! What’s the matter with it?”

“Too ornate, sir.”

“Nonsense! A cheerful pink. Nothing more.”

“Unsuitable, sir.”

“Jeeves, this is the tie I wear!”

“Very good, sir.”

Dashed unpleasant. I could see that the man was wounded. But I was firm. I tied the tie, got into the coat and waistcoat, and went into the sitting-room.

“Halloa! Halloa! Halloa!” I said. “What?”

“Ah! How do you do, Mr. Wooster? You have never met my son Wilmot, I think? Motty, darling, this is Mr. Wooster.”

Lady Malvern was a hearty, happy, healthy, overpowering sort of dashed female, not so very tall but making up for it by measuring about six feet from the O. P. to the Prompt Side. She fitted into my biggest arm-chair as if it had been built round her by someone who knew they were wearing arm-chairs tight about the hips that season. She had bright, bulging eyes and a lot of yellow hair, and when she spoke she showed about fifty-seven front teeth. She was one of those women who kind of numb a fellow’s faculties. She made me feel as if I were ten years old and had been brought into the drawing-room in my Sunday clothes to say how-d’you-do. Altogether by no means the sort of thing a chappie would wish to find in his sitting-room before breakfast.

Motty, the son, was about twenty-three, tall and thin and meek-looking. He had the same yellow hair as his mother, but he wore it plastered down and parted in the middle. His eyes bulged, too, but they weren’t bright. They were a dull grey with pink rims. His chin gave up the struggle about half-way down, and he didn’t appear to have any eyelashes. A mild, furtive, sheepish sort of blighter, in short.

“Awfully glad to see you,” I said. “So you’ve popped over, eh? Making a long stay in America?”

“About a month. Your aunt gave me your address and told me to be sure and call on you.”

I was glad to hear this, as it showed that Aunt Agatha was beginning to come round a bit. There had been some unpleasantness a year before, when she had sent me over to New York to disentangle my Cousin Gussie from the clutches of a girl on the music-hall stage. When I tell you that by the time I had finished my operations Gussie had not only married the girl but had gone on the stage himself and was doing well, you’ll understand that Aunt Agatha was upset to no small extent. I simply hadn’t dared go back and face her, and it was a relief to find that time had healed the wound and all that sort of thing enough to make her tell her pals to look me up. What I mean is, much as I liked America, I didn’t want to have England barred to me for the rest of my natural; and, believe me, England is a jolly sight too small for anyone to live in with Aunt Agatha, if she’s really on the warpath. So I was braced on hearing these kind words and smiled genially on the assemblage.

“Your aunt said that you would do anything that was in your power to be of assistance to us.”

“Rather? Oh, rather! Absolutely!”

“Thank you so much. I want you to put dear Motty up for a little while.”

I didn’t get this for a moment.

“Put him up? For my clubs?”

“No, no! Darling Motty is essentially a home bird. Aren’t you, Motty darling?”

Motty, who was sucking the knob of his stick, uncorked himself.

“Yes, mother,” he said, and corked himself up again.

“I should not like him to belong to clubs. I mean put him up here. Have him to live with you while I am away.”

These frightful words trickled out of her like honey. The woman simply

didn’t seem to understand the ghastly nature of her proposal. I gave

Motty the swift east-to-west. He was sitting with his mouth nuzzling

the stick, blinking at the wall. The thought of having this planted on

me for an indefinite period appalled me. Absolutely appalled me, don’t

you know. I was just starting to say that the shot wasn’t on the board

at any price, and that the first sign Motty gave of trying to nestle

into my little home I would yell for the police, when she went on,

rolling placidly over me, as it were.

These frightful words trickled out of her like honey. The woman simply

didn’t seem to understand the ghastly nature of her proposal. I gave

Motty the swift east-to-west. He was sitting with his mouth nuzzling

the stick, blinking at the wall. The thought of having this planted on

me for an indefinite period appalled me. Absolutely appalled me, don’t

you know. I was just starting to say that the shot wasn’t on the board

at any price, and that the first sign Motty gave of trying to nestle

into my little home I would yell for the police, when she went on,

rolling placidly over me, as it were.

There was something about this woman that sapped a chappie’s will-power.

“I am leaving New York by the midday train, as I have to pay a visit to Sing-Sing prison. I am extremely interested in prison conditions in America. After that I work my way gradually across to the coast, visiting the points of interest on the journey. You see, Mr. Wooster, I am in America principally on business. No doubt you read my book, ‘India and the Indians’? My publishers are anxious for me to write a companion volume on the United States. I shall not be able to spend more than a month in the country, as I have to get back for the season, but a month should be ample. I was less than a month in India, and my dear friend Sir Roger Cremorne wrote his ‘America from Within’ after a stay of only two weeks. I should love to take dear Motty with me, but the poor boy gets so sick when he travels by train. I shall have to pick him up on my return.”

From where I sat I could see Jeeves in the dining-room, laying the breakfast-table. I wished I could have had a minute with him alone. I felt certain that he would have been able to think of some way of putting a stop to this woman.

“It will be such a relief to know that Motty is safe with you, Mr. Wooster. I know what the temptations of a great city are. Hitherto dear Motty has been sheltered from them. He has lived quietly with me in the country. I know that you will look after him carefully, Mr. Wooster. He will give very little trouble.” She talked about the poor blighter as if he wasn’t there. Not that Motty seemed to mind. He had stopped chewing his walking-stick and was sitting there with his mouth open. “He is a vegetarian and a teetotaller and is devoted to reading. Give him a nice book and he will be quite contented.” She got up. “Thank you so much, Mr. Wooster! I don’t know what I should have done without your help. Come, Motty! We have just time to see a few of the sights before my train goes. But I shall have to rely on you for most of my information about New York, darling. Be sure to keep your eyes open and take notes of your impressions! It will be such a help. Good-bye, Mr. Wooster. I will send Motty back early in the afternoon.”

They went out, and I howled for Jeeves.

“Jeeves! What about it?”

“Sir?”

“What’s to be done? You heard it all, didn’t you? You were in the dining-room most of the time. That pill is coming to stay here.”

“Pill, sir?”

“The excrescence.”

“I beg your pardon, sir?”

I looked at Jeeves sharply. This sort of thing wasn’t like him. It was as if he were deliberately trying to give me the pip. Then I understood. The man was really upset about that tie. He was trying to get his own back.

“Lord Pershore will be staying here from to-night, Jeeves,” I said, coldly.

“Very good, sir. Breakfast is ready, sir.”

I could have sobbed into the bacon and eggs. That there wasn’t any sympathy to be got out of Jeeves was what put the lid on it. For a moment I almost weakened and told him to destroy the hat and tie if he didn’t like them, but I pulled myself together again. I was dashed if I was going to let Jeeves treat me like a bally one-man chain-gang!

But, what with brooding on Jeeves and brooding on Motty, I was in a pretty reduced sort of state. The more I examined the situation, the more blighted it became. There was nothing I could do. If I slung Motty out, he would report to his mother, and she would pass it on to Aunt Agatha, and I didn’t like to think what would happen then. Sooner or later, I should be wanting to go back to England, and I didn’t want to get there and find Aunt Agatha waiting on the quay for me with a stuffed eelskin. There was absolutely nothing for it but to put the fellow up and make the best of it.

About midday Motty’s luggage arrived, and soon afterward a large parcel of what I took to be nice books. I brightened up a little when I saw it. It was one of those massive parcels, and looked as if it had enough in it to keep the chappie busy for a year. I felt a trifle more cheerful, and I got my Country Gentleman hat and stuck it on my head, and gave the pink tie a twist, and reeled out to take a bite of lunch with one or two of the lads at a neighbouring hostelry; and what with excellent browsing and sluicing and cheery conversation and what-not, the afternoon passed quite happily. By dinner-time I had almost forgotten blighted Motty’s existence.

I dined at the club and looked in at a show afterward, and it wasn’t till fairly late that I got back to the flat. There were no signs of Motty, and I took it that he had gone to bed.

It seemed rummy to me, though, that the parcel of nice books was still there with the string and paper on it. It looked as if Motty, after seeing mother off at the station, had decided to call it a day.

Jeeves came in with the nightly whisky-and-soda. I could tell by the chappie’s manner that he was still upset.

“Lord Pershore gone to bed, Jeeves?” I asked, with reserved hauteur and what-not.

“No, sir. His lordship has not yet returned.”

“Not returned? What do you mean?”

“His lordship came in shortly after six-thirty, and, having dressed, went out again.”

At this moment there was a noise outside the front door, a sort of scrabbling noise, as if somebody were trying to paw his way through the woodwork. Then a sort of thud.

“Better go and see what that is, Jeeves.”

“Very good, sir.”

He went out and came back again.

“If you would not mind stepping this way, sir, I think we might be able to carry him in.”

“Carry him in?”

“His lordship is lying on the mat, sir.”

I went to the front door. The man was right. There was Motty huddled up outside on the floor. He was moaning a bit.

“He’s had some sort of dashed fit,” I said. I took another look. “Jeeves! Someone’s been feeding him meat!”

“Sir?”

“He’s a vegetarian, you know. He must have been digging into a steak or something. Call up a doctor!”

“I hardly think it will be necessary, sir. If you would take his lordship’s legs, while I——”

“Great Scot, Jeeves! You don’t think—he can’t be——”

“I am inclined to think so, sir.”

And, by Jove, he was right! Once on the right track, you couldn’t mistake it. Motty was under the surface.

It was the deuce of a shock.

“You never can tell, Jeeves!”

“Very seldom, sir.”

“Remove the eye of authority and where are you?”

“Precisely, sir.”

“Where is my wandering boy to-night and all that sort of thing, what?”

“It would seem so, sir.”

“Well, we had better bring him in, eh?”

“Yes, sir.”

So we lugged him in, and Jeeves put him to bed, and I lit a cigarette and sat down to think the thing over. I had a kind of foreboding. It seemed to me that I had let myself in for something pretty rocky.

Next morning, after I had sucked down a thoughtful cup of tea, I went into Motty’s room to investigate. I expected to find the fellow a wreck, but there he was, sitting up in bed, quite chirpy, reading Gingery Stories.

“What ho!” I said.

“What ho!” said Motty.

“What ho! What ho!”

“What ho! What ho! What ho!”

After that it seemed rather difficult to go on with the conversation.

“How are you feeling this morning?” I asked.

“Topping!” replied Motty, blithely and with abandon. “I say, you know, that fellow of yours—Jeeves, you know—is a corker. I had a most frightful headache when I woke up, and he brought me a sort of rummy dark drink, and it put me right again at once. Said it was his own invention. I must see more of that lad. He seems to me distinctly one of the ones!”

I couldn’t believe that this was the same blighter who had sat and sucked his stick the day before.

“You ate something that disagreed with you last night, didn’t you?” I said, by way of giving him a chance to slide out of it if he wanted to. But he wouldn’t have it at any price.

“No!” he replied, firmly. “I didn’t do anything of the kind. I drank too much! Much too much! Lots and lots too much! And, what’s more, I’m going to do it again! I’m going to do it every night. If ever you see me sober, old top,” he said, with a kind of holy exaltation, “tap me on the shoulder and say, ‘Tut! Tut!’ and I’ll apologize and remedy the defect.”

“But I say, you know, what about me?”

“What about you?”

“Well, I’m so to speak, as it were, kind of responsible for you. What I mean to say is, if you go doing this sort of thing I’m apt to get in the soup somewhat.”

“I can’t help your troubles,” said Motty, firmly. “Listen to me, old thing: this is the first time in my life that I’ve had a real chance to yield to the temptations of a great city. What’s the use of a great city having temptations if fellows don’t yield to them? Makes it so bally discouraging for a great city. Besides, mother told me to keep my eyes open and collect impressions.”

I sat on the edge of the bed. I felt dizzy.

“I know just how you feel, old dear,” said Motty, consolingly. “And, if my principles would permit it, I would simmer down for your sake. But duty first! This is the first time I’ve been let out alone, and I mean to make the most of it. We’re only young once. Why interfere with life’s morning? Young man, rejoice in thy youth! Tra-la! What ho!”

Put like that, it did seem reasonable.

“All my bally life, dear boy,” Motty went on, “I’ve been cooped up in the ancestral home at Much Middlefold, in Shropshire, and till you’ve been cooped up in Much Middlefold you don’t know what cooping is! The only time we get any excitement is when one of the choir-boys is caught sucking chocolate during the sermon. When that happens, we talk about it for days. I’ve got about a month of New York, and I mean to store up a few happy memories for the long winter evenings. This is my only chance to collect a past, and I’m going to do it. Now tell me, old sport, as man to man, how does one get in touch with that very decent chappie Jeeves? Does one ring a bell or shout a bit? I should like to discuss the subject of a good stiff b.-and-s. with him!”

I had had a sort of vague idea, don’t you know, that if I stuck close to Motty and went about the place with him, I might act as a bit of a damper on the gaiety. What I mean is, I thought that if, when he was being the life and soul of the party, he were to catch my reproving eye he might ease up a trifle on the revelry. So the next night I took him along to supper with me. It was the last time. I’m a quiet, peaceful sort of chappie who has lived all his life in London, and I can’t stand the pace these swift sportsmen from the rural districts set. What I mean to say is, I’m all for rational enjoyment and so forth, but I think a chappie makes himself conspicuous when he throws soft-boiled eggs at the electric fan. And decent mirth and all that sort of thing are all right, but I do bar dancing on tables and having to dash all over the place dodging waiters, managers, and chuckers-out, just when you want to sit still and digest.

Directly I managed to tear myself away that night and get home, I made up my mind that this was jolly well the last time that I went about with Motty. The only time I met him late at night after that was once when I passed the door of a fairly low-down sort of restaurant and had to step aside to dodge him as he sailed through the air en route for the opposite pavement, with a muscular sort of looking chappie peering out after him with a kind of gloomy satisfaction.

In a way, I couldn’t help sympathizing with the fellow. He had about four weeks to have the good time that ought to have been spread over about ten years, and I didn’t wonder at his wanting to be pretty busy. I should have been just the same in his place. Still, there was no denying that it was a bit thick. If it hadn’t been for the thought of Lady Malvern and Aunt Agatha in the background, I should have regarded Motty’s rapid work with an indulgent smile. But I couldn’t get rid of the feeling that, sooner or later, I was the lad who was scheduled to get it behind the ear. And what with brooding on this prospect, and sitting up in the old flat waiting for the familiar footstep, and putting it to bed when it got there, and stealing into the sick-chamber next morning to contemplate the wreckage, I was beginning to lose weight. Absolutely becoming the good old shadow, I give you my honest word. Starting at sudden noises and what-not.

And no sympathy from Jeeves. That was what cut me to the quick. The man was still thoroughly pipped about the hat and tie, and simply wouldn’t rally round. One morning I wanted comforting so much that I sank the pride of the Woosters and appealed to the fellow direct.

“Jeeves,” I said, “this is getting a bit thick!”

“Sir?” Business and cold respectfulness.

“You know what I mean. This lad seems to have chucked all the principles of a well-spent boyhood. He has got it up his nose!”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, I shall get blamed, don’t you know. You know what my Aunt Agatha is!”

“Yes, sir.”

“Very well, then.”

I waited a moment, but he wouldn’t unbend.

“Jeeves,” I said, “haven’t you any scheme up your sleeve for coping with this blighter?”

“No, sir.”

And he shimmered off to his lair. Obstinate devil! So dashed absurd, don’t you know. It wasn’t as if there was anything wrong with that Country Gentleman hat. It was a remarkably priceless effort, and much admired by the lads. But, just because he preferred the Longacre, he left me flat.

It was shortly after this that young Motty got the idea of bringing pals back in the small hours to continue the gay revels in the home. This was where I began to crack under the strain. You see, the part of town where I was living wasn’t the right place for that sort of thing. I knew lots of chappies down Washington Square way who started the evening at about 2 a.m.—artists and writers and what-not, who frolicked considerably till checked by the arrival of the morning milk. That was all right. They like that sort of thing down there. The neighbours can’t get to sleep unless there’s someone dancing Hawaiian dances over their heads. But on Fifty-seventh Street the atmosphere wasn’t right, and when Motty turned up at three in the morning with a collection of hearty lads, who only stopped singing their college song when they started singing “The Old Oaken Bucket,” there was a marked peevishness among the old settlers in the flats. The management was extremely terse over the telephone at breakfast-time, and took a lot of soothing.

The next night I came home early, after a lonely dinner at a place which I’d chosen because there didn’t seem any chance of meeting Motty there. The sitting-room was quite dark, and I was just moving to switch on the light, when there was a sort of explosion and something collared hold of my trouser-leg. Living with Motty had reduced me to such an extent that I was simply unable to cope with this thing. I jumped backward with a loud yell of anguish, and tumbled out into the hall just as Jeeves came out of his den to see what the matter was.

“Did you call, sir?”

“Jeeves! There’s something in there that grabs you by the leg!”

“That would be Rollo, sir.”

“Eh?”

“I would have warned you of his presence, but I did not hear you come in. His temper is a little uncertain at present, as he has not yet settled down.”

“Who the deuce is Rollo?”

“His lordship’s bull-terrier, sir. His lordship won him in a raffle, and tied him to the leg of the table. If you will allow me, sir, I will go in and switch on the light.”

There really is nobody like Jeeves. He walked straight into the sitting-room, the biggest feat since Daniel and the lions’ den, without a quiver. What’s more, his magnetism or whatever they call it was such that the dashed animal, instead of pinning him by the leg, calmed down as if he had had a bromide, and rolled over on his back with all his paws in the air. If Jeeves had been his rich uncle he couldn’t have been more chummy. Yet directly he caught sight of me again, he got all worked up and seemed to have only one idea in life—to start chewing me where he had left off.

“Rollo is not used to you yet, sir,” said Jeeves, regarding the bally quadruped in an admiring sort of way. “He is an excellent watchdog.”

“I don’t want a watchdog to keep me out of my rooms.”

“No, sir.”

“Well, what am I to do?”

“No doubt in time the animal will learn to discriminate, sir. He will learn to distinguish your peculiar scent.”

“What do you mean—my peculiar scent? Correct the impression that I intend to hang about in the hall while life slips by, in the hope that one of these days that dashed animal will decide that I smell all right.” I thought for a bit. “Jeeves!”

“Sir?”

“I’m going away—to-morrow morning by the first train. I shall go and stop with Mr. Todd in the country.”

“Do you wish me to accompany you, sir?”

“No.”

“Very good, sir.”

“I don’t know when I shall be back. Forward my letters.”

“Yes, sir.”

As a matter of fact, I was back within the week. Rocky Todd, the pal I went to stay with, is a rummy sort of a chap who lives all alone in the wilds of Long Island, and likes it; but a little of that sort of thing goes a long way with me. Dear old Rocky is one of the best, but after a few days in his cottage in the woods, miles away from anywhere, New York, even with Motty on the premises, began to look pretty good to me. The days down on Long Island have forty-eight hours in them; you can’t get to sleep at night because of the bellowing of the crickets; and you have to walk two miles for a drink and six for an evening paper. I thanked Rocky for his kind hospitality, and caught the only train they have down in those parts. It landed me in New York about dinner-time. I went straight to the old flat. Jeeves came out of his lair. I looked round cautiously for Rollo.

“Where’s that dog, Jeeves? Have you got him tied up?”

“The animal is no longer here, sir. His lordship gave him to the porter, who sold him. His lordship took a prejudice against the animal on account of being bitten by him in the calf of the leg.”

I don’t think I’ve ever been so bucked by a bit of news. I felt I had misjudged Rollo. Evidently, when you got to know him better, he had a lot of intelligence in him.

“Ripping!” I said. “Is Lord Pershore in, Jeeves?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you expect him back to dinner?”

“No, sir.”

“Where is he?”

“In prison, sir.”

Have you ever trodden on a rake and had the handle jump up and hit you? That’s how I felt then.

“In prison!”

“Yes, sir.”

“You don’t mean—in prison?”

“Yes, sir.”

I lowered myself into a chair.

“Why?” I said.

“He assaulted a constable, sir.”

“Lord Pershore assaulted a constable!”

“Yes, sir.”

I digested this.

“But, Jeeves, I say! This is frightful!”

“Sir?”

“What will Lady Malvern say when she finds out?”

“I do not fancy that her ladyship will find out, sir.”

“But she’ll come back and want to know where he is.”

“I rather fancy, sir, that his lordship’s bit of time will have run out by then.”

“But supposing it hasn’t?”

“In that event, sir, it may be judicious to prevaricate a little.”

“How?”

“If I might make the suggestion, sir, I should inform her ladyship that his lordship has left for a short visit to Boston.”

“Why Boston?”

“Very interesting and respectable centre, sir.”

“Jeeves, I believe you’ve hit it.”

“I fancy so, sir.”

“Why, this is really the best thing that could have happened. If this hadn’t turned up to prevent him, young Motty would have been in a sanatorium by the time Lady Malvern got back.”

“Exactly, sir.”

The more I looked at it in that way, the sounder this prison wheeze seemed to me. There was no doubt in the world that prison was just what the doctor ordered for Motty. It was the only thing that could have pulled him up. I was sorry for the poor blighter, but after all, I reflected, a chappie who had lived all his life with Lady Malvern, in a small village in the interior of Shropshire, wouldn’t have much to kick at in a prison. Altogether, I began to feel absolutely braced again. Life became like what the poet johnnie says—one grand, sweet song. Things went on so comfortably and peacefully for a couple of weeks that I give you my word that I’d almost forgotten such a person as Motty existed. The only flaw in the scheme of things was that Jeeves was still pained and distant. It wasn’t anything he said or did, mind you, but there was a rummy something about him all the time. Once when I was tying the pink tie I caught sight of him in the looking-glass. There was a kind of grieved look in his eye.

And then Lady Malvern came back, a good bit ahead of schedule. I hadn’t been expecting her for days. I’d forgotten how time had been slipping along. She turned up one morning while I was still in bed sipping tea and thinking of this and that. Jeeves flowed in with the announcement that he had just loosed her into the sitting-room. I draped a few garments round me and went in.

There she was, sitting in the same arm-chair, looking as massive as ever. The only difference was that she didn’t uncover the teeth as she had done the first time.

“Good morning,” I said. “So you’ve got back, what?”

“I have got back.”

There was something sort of bleak about her tone, rather as if she had swallowed an east wind. This I took to be due to the fact that she probably hadn’t breakfasted. It’s only after a bit of breakfast that I’m able to regard the world with that sunny cheeriness which makes a fellow the universal favourite. I’m never much of a lad till I’ve engulfed an egg or two and a beaker of coffee.

“I suppose you haven’t breakfasted?”

“I have not yet breakfasted.”

“Won’t you have an egg or something? Or a sausage or something? Or something?”

“No, thank you.”

She spoke as if she belonged to an anti-sausage society or a league for the suppression of eggs. There was a bit of a silence.

“I called on you last night,” she said, “but you were out.”

“Awfully sorry! Had a pleasant trip?”

“Extremely, thank you.”

“See everything? Niag’ra Falls, Yellowstone Park, and the jolly old Grand Canyon, and what-not?”

“I saw a great deal.”

There was another slightly frappé silence. Jeeves floated silently into the dining-room and began to lay the breakfast-table.

“I hope Wilmot was not in your way, Mr. Wooster?”

I had been wondering when she was going to mention Motty.

“Rather not! Great pals! Hit it off splendidly.”

“You were his constant companion, then?”

“Absolutely! We were always together. Saw all the sights, don’t you know. We’d take in the Museum of Art in the morning, and have a bit of lunch at some good vegetarian place, and then toddle along to a sacred concert in the afternoon, and home to an early dinner. We usually played dominoes after dinner. And then the early bed and the refreshing sleep. We had a great time. I was awfully sorry when he went away to Boston.”

“Oh! Wilmot is in Boston?”

“Yes. I ought to have let you know, but of course we didn’t know where you were. You were dodging all over the place like a snipe—I mean, don’t you know, dodging all over the place, and we couldn’t get at you. Yes, Motty went off to Boston.”

“You’re sure he went to Boston?”

“Oh, absolutely.” I called out to Jeeves, who was now messing about in the next room with forks and so forth: “Jeeves, Lord Pershore didn’t change his mind about going to Boston, did he?”

“No, sir.”

“I thought I was right. Yes, Motty went to Boston.”

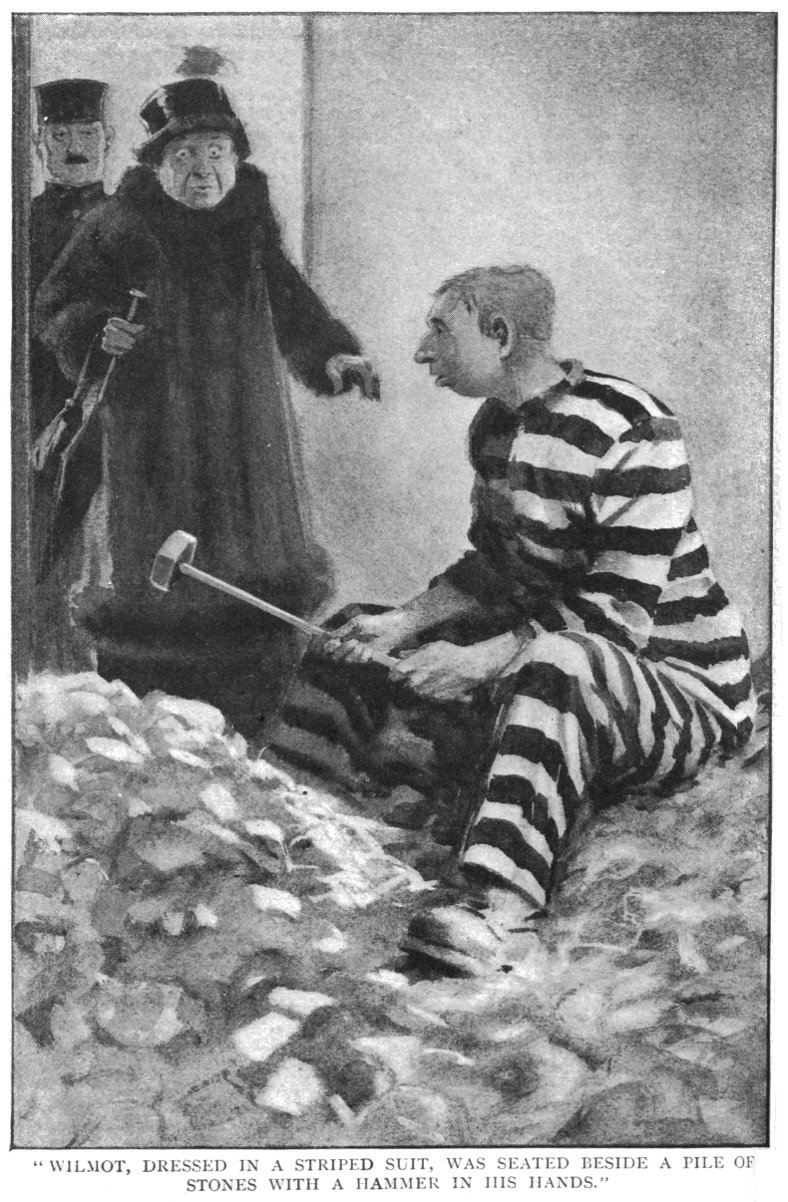

“Then how do you account, Mr. Wooster, for the fact that when I went yesterday afternoon to Blackwell’s Island prison, to secure material for my book, I saw poor, dear Wilmot there, dressed in a striped suit, seated beside a pile of stones with a hammer in his hands?”

I tried to think of something to say, but nothing came. A chappie has to be a lot broader about the forehead than I am to handle a jolt like this. I strained the old bean till it creaked, but between the collar and the hair parting nothing stirred. I was dumb. Which was lucky, because I wouldn’t have had a chance to get any persiflage out of my system. Lady Malvern collared the conversation. She had been bottling it up, and now it came out with a rush:—

“So this is how you have looked after my poor, dear boy, Mr. Wooster! So this is how you have abused my trust! I left him in your charge, thinking that I could rely on you to shield him from evil. He came to you innocent, unversed in the ways of the world, confiding, unused to the temptations of a large city, and you led him astray!”

I hadn’t any remarks to make. All I could think of was the picture of Aunt Agatha drinking all this in and reaching out to sharpen the hatchet against my return.

“You deliberately——”

Far away in the misty distance a soft voice spoke:—

“If I might explain, your ladyship.”

Jeeves had projected himself in from the dining-room and materialized on the rug. Lady Malvern tried to freeze him with a look, but you can’t do that sort of thing to Jeeves. He is look-proof.

“I fancy, your ladyship, that you have misunderstood Mr. Wooster, and that he may have given you the impression that he was in New York when his lordship was—removed. When Mr. Wooster informed your ladyship that his lordship had gone to Boston, he was relying on the version I had given him of his lordship’s movements. Mr. Wooster was away, visiting a friend in the country, at the time, and knew nothing of the matter till your ladyship informed him.”

Lady Malvern gave a kind of grunt. It didn’t rattle Jeeves.

“I feared Mr. Wooster might be disturbed if he knew the truth, as he is so attached to his lordship and has taken such pains to look after him, so I took the liberty of telling him that his lordship had gone away for a visit. It might have been hard for Mr. Wooster to believe that his lordship had gone to prison voluntarily and from the best motives, but your ladyship, knowing him better, will readily understand.”

“What!” Lady Malvern goggled at him. “Did you say that Lord Pershore went to prison voluntarily?”

“If I might explain, your ladyship. I think that your ladyship’s parting words made a deep impression on his lordship. I have frequently heard him speak to Mr. Wooster of his desire to do something to follow your ladyship’s instructions and collect material for your ladyship’s book on America. Mr. Wooster will bear me out when I say that his lordship was frequently extremely depressed at the thought that he was doing so little to help.”

“Absolutely, by Jove! Quite pipped about it!” I said.

“The idea of making a personal examination into the prison system of the country—from within—occurred to his lordship very suddenly one night. He embraced it eagerly. There was no restraining him.”

Lady Malvern looked at Jeeves, then at me, then at Jeeves again. I could see her struggling with the thing.

“Surely, your ladyship,” said Jeeves, “it is more reasonable to suppose that a gentleman of his lordship’s character went to prison of his own volition than that he committed some breach of the law which necessitated his arrest?”

Lady Malvern blinked. Then she got up.

“Mr. Wooster,” she said, “I apologize. I have done you an injustice. I should have known Wilmot better. I should have had more faith in his pure, fine spirit.”

“Absolutely!” I said.

“Your breakfast is ready, sir,” said Jeeves.

I sat down and dallied in a dazed sort of way with a poached egg.

“Jeeves,” I said, “you are certainly a life-saver!”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Nothing would have convinced my Aunt Agatha that I hadn’t lured that blighter into riotous living.”

“I fancy you are right, sir.”

I champed my egg for a bit. I was most awfully moved, don’t you know, by the way Jeeves had rallied round. Something seemed to tell me that this was an occasion that called for rich rewards. For a moment I hesitated. Then I made up my mind.

“Jeeves!”

“Sir?”

“That pink tie!”

“Yes, sir?”

“Burn it!”

“Thank you, sir.”

“And, Jeeves!”

“Yes, sir?”

“Take a taxi and get me that Longacre hat, as worn by John Drew!”

“Thank you very much, sir.”

I felt most awfully braced. I felt as if the clouds had rolled away and all was as it used to be. I felt like one of those chappies in the novels who calls off the fight with his wife in the last chapter and decides to forget and forgive. I felt I wanted to do all sorts of other things to show Jeeves that I appreciated him.

“Jeeves,” I said, “it isn’t enough. Is there anything else you would like?”

“Yes, sir. If I may make the suggestion—fifty dollars.”

“Fifty dollars?”

“It will enable me to pay a debt of honour, sir. I owe it to his lordship.”

“You owe Lord Pershore fifty dollars?”

“Yes, sir. I happened to meet him in the street the night his lordship was arrested. I had been thinking a good deal about the most suitable method of inducing him to abandon his mode of living, sir. His lordship was a little over-excited at the time, and I fancy that he mistook me for a friend of his. At any rate when I took the liberty of wagering him fifty dollars that he would not punch a passing policeman in the eye, he accepted the bet very cordially and won it.”

I produced my pocket-book and counted out a hundred.

“Take this, Jeeves,” I said; “fifty isn’t enough. Do you know, Jeeves, you’re—well, you absolutely stand alone!”

“I endeavour to give satisfaction, sir,” said Jeeves.

Compare the American magazine appearance of this story.

Annotations to the book version of the story can be found in Carry On, Jeeves.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums