The Strand Magazine, December 1929

I WAS lunching at my Aunt Dahlia’s, and despite the fact that Anatole, her outstanding cook, had rather excelled himself in the matter of the bill-of-fare or menu, I’m bound to say the food was more or less turning to ashes in my mouth. You see, I had some bad news to break to her—always a prospect that takes the edge off the appetite. She wouldn’t be pleased, I knew, and, when not pleased, Aunt Dahlia, having spent most of her youth in the hunting-field, has a crispish way of expressing herself.

However, I supposed I had better have a dash at it and get it over.

“Aunt Dahlia,” I said.

“Hullo?”

“You know that cruise of yours?”

“Yes.”

“That yachting cruise you are planning?”

“Yes.”

“That jolly cruise in your yacht in the Mediterranean to which you so kindly invited me, and to which I have been looking forward with such keen anticipation?”

“What about it?”

I swallowed a chunk of côtelette-suprême-aux-choux-fleurs and slipped her the distressing info’.

“I’m frightfully sorry, Aunt Dahlia,” I said, “but I sha’n’t be able to come.”

She goggled.

“What!”

“I’m afraid not.”

“You poor, miserable hell-hound, what do you mean, you won’t be able to come?”

“Well, I won’t.”

“Why not?”

“Matters of the most extreme urgency render my presence in the metropolis imperative.”

She sniffed.

“I suppose what you really mean is that you’re hanging round some unfortunate girl again?”

I didn’t like the way she put it, but I admit I was stunned by her penetration, if that’s the word I want. I mean the sort of thing detectives have.

“Yes, Aunt Dahlia,” I said. “You have my secret. I do indeed love.”

“Who is she?”

“A Miss Pendlebury. Christian name, Gwladys. She spells it with a ‘w.’ ”

“With a ‘g.’ you mean.”

“With a ‘w.’ and a ‘g.’ ”

“Not Gwladys?”

“That’s it.”

The relative uttered a yowl.

“You sit there and tell me you haven’t enough sense to steer clear of a girl who calls herself Gwladys? Listen, Bertie,” said Aunt Dahlia, earnestly. “I’m an older woman than you are—well, you know what I mean—and I can tell you a thing or two. And one of them is that no good can come of association with anything labelled Gwladys or Ysobel or Ethyl or Mabelle or Kathryn. But particularly Gwladys. What sort of girl is she?”

“Slightly divine.”

“She isn’t that female I saw driving you at sixty miles p.h. in the Park the other day? In a red two-seater.”

“She did drive me in the Park the other day. I thought it rather a hopeful sign. And her Widgeon Seven is red.”

Aunt Dahlia looked relieved.

“Oh, well, then, she’ll probably break your silly fat neck before she can get you to the altar. That’s some consolation. Where did you meet her?”

“At a party in Chelsea. She’s an artist.”

“Ye gods!”

“And swings a jolly fine brush, let me tell you. She’s painted a portrait of me. Jeeves and I hung it up in the flat this morning. I have an idea Jeeves doesn’t like it.”

“Well, if it’s anything like you I don’t see why he should. An artist! Calls herself Gwladys. And drives a car in the sort of way Segrave would if he was pressed for time.” She brooded awhile. “Well, it’s all very sad, but I can’t see why you won’t come on the yacht.”

I explained.

“It would be madness to leave the metrop. at this juncture,” I said. “You know what girls are. They forget the absent face. And I’m not at all easy in my mind about a certain cove of the name of Lucius Pim. Apart from the fact that he’s an artist, too, which forms a bond, his hair waves. One must never discount wavy hair, Aunt Dahlia. Moreover, this bloke is one of those strong, masterful men. He treats Gwladys as if she were less than the dust beneath his taxi wheels. He criticizes her hats and says nasty things about her chiaroscuro. For some reason, I’ve often noticed, this always seems to fascinate girls, and it has sometimes occurred to me that, being myself more the parfait gentle knight, if you know what I mean, I am in grave danger of getting the short end. Taking all these things into consideration, then, I cannot possibly breeze off to the Mediterranean, leaving this Pim a clear field. You must see that?”

Aunt Dahlia laughed. Rather a nasty laugh. Scorn in its timbre, or so it seemed to me.

“I shouldn’t worry,” she said. “You don’t suppose for a moment that Jeeves will sanction the match?”

I was stung.

“Do you imply, Aunt Dahlia,” I said, and I can’t remember if I rapped the table with the handle of my fork or not, but I rather think I did, “that I allow Jeeves to boss me to the extent of stopping me marrying somebody I want to marry?”

“Well, he stopped you wearing a moustache. And purple socks. And soft-fronted shirts with dress-clothes.”

“That is a different matter altogether.”

“Well, I’m prepared to make a small bet with you, Bertie. Jeeves will stop this match.”

“What absolute rot!”

“And if he doesn’t like that portrait, he will get rid of it.”

“I never heard such dashed nonsense in my life.”

“And, finally, you wretched, pie-faced wambler, he will present you on board my yacht at the appointed hour. I don’t know how he will do it, but you will be there, all complete with yachting-cap and spare pair of socks.”

“Let us change the subject, Aunt Dahlia,” I said, coldly.

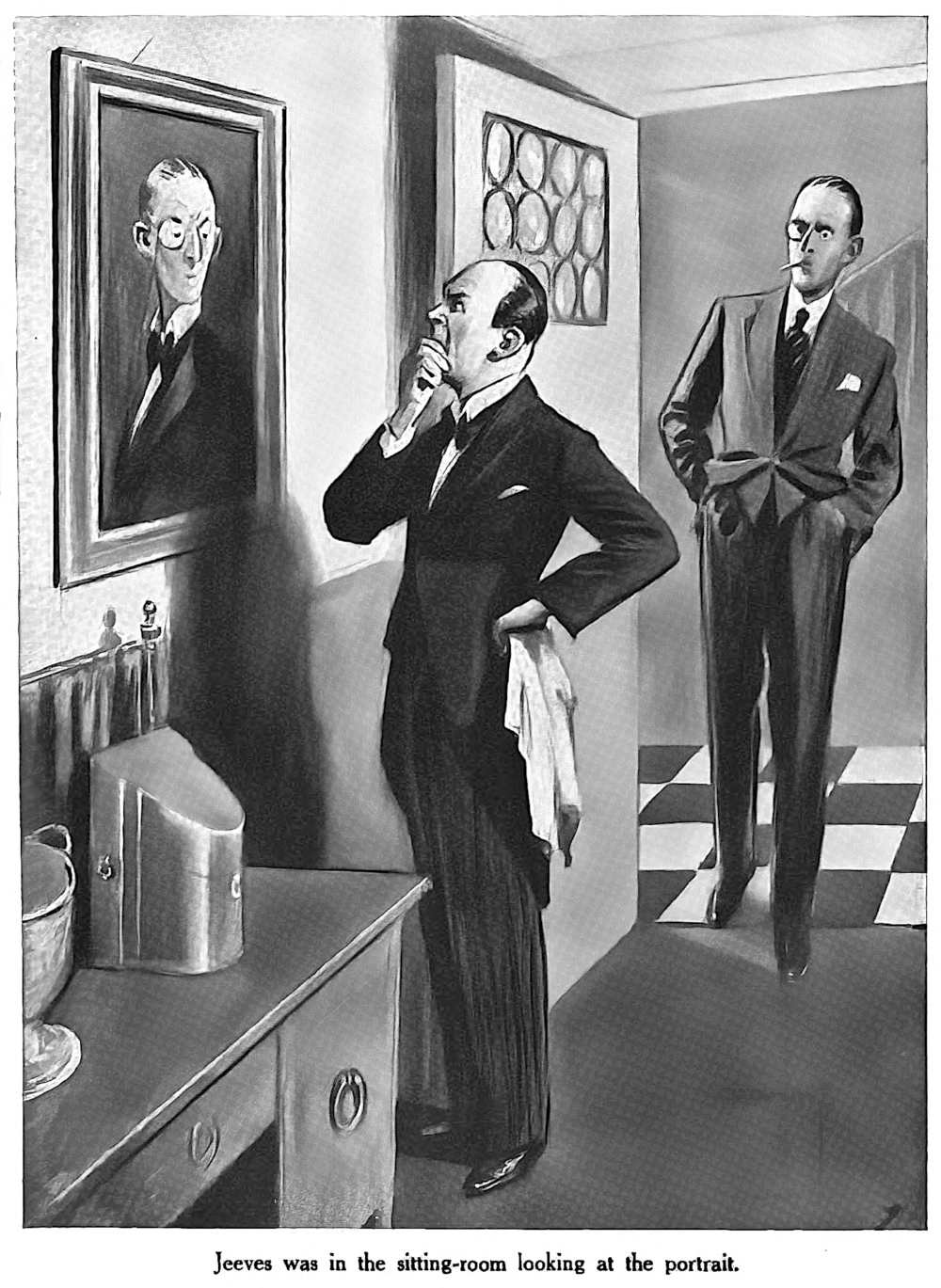

BEING a good deal stirred up by the attitude of the flesh-and-blood at the luncheon-table, I had to go for a bit of a walk in the Park after leaving, to soothe the nervous system. By about four-thirty the ganglions had ceased to vibrate, and I returned to the flat. Jeeves was in the sitting-room, looking at the portrait.

I felt a trifle embarrassed in the man’s presence, because just before leaving I had informed him of my intention to scratch the yacht trip, and he had taken it on the chin a bit. You see, he had been looking forward to it rather. From the moment I had accepted the invitation, there had been a sort of nautical glitter in his eye, and I’m not sure I hadn’t heard him trolling chanties in the kitchen. I think some ancestor of his must have been one of Nelson’s tars, or something, for he has always had the urge of the salt sea in his blood. I have noticed him on liners, when we were going to America, striding the deck with a sailorly roll and giving the distinct impression of being just about to heave the main-brace or splice the binnacle.

So, though I had explained my reasons, taking the man fully into my confidence and concealing nothing, I knew that he was distinctly peeved; and my first act on entering was to do the cheery a bit. I joined him in front of the portrait.

“Looks good, Jeeves, what?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Nothing like a spot of art for brightening the home.”

“No, sir.”

“Seems to lend the room a certain what-shall-I-say?”

“Yes, sir.”

The responses were all right, but his manner was far from hearty, and I decided to tackle him squarely. I mean, dash it. I mean, I don’t know if you have ever had your portrait painted, but if you have you will understand my feelings. The spectacle of one’s portrait hanging on the wall creates in one a sort of paternal fondness for the thing; and what you demand from the outside public is approval and enthusiasm—not the curling lip, the twitching nostril, and the kind of supercilious look which you see in the eye of a dead fish. Especially is this so when the artist is a girl for whom you have conceived sentiments deeper and warmer than those of ordinary friendship.

“Jeeves,” I said, “you don’t like this spot of art.”

“Oh, yes, sir.”

“No. Subterfuge is useless. I can read you like a book. For some reason this spot of art fails to appeal to you. What do you object to about it?”

“Is not the colour-scheme a trifle bright, sir?

“I had not observed it, Jeeves. Anything else?”

“Well, in my opinion, sir, Miss Pendlebury has given you a somewhat too hungry expression.”

“Hungry?”

“A little like that of a dog regarding a distant bone, sir.”

I checked the fellow.

“There is no resemblance whatever, Jeeves, to a dog regarding a distant bone. The look to which you allude is wistful and denotes soul.”

“I see, sir.”

I proceeded to another subject.

“Miss Pendlebury said she might look in this afternoon to inspect the portrait. Did she turn up?”

“Yes, sir.”

“But has left?”

“Yes, sir.”

“She didn’t say anything about coming back?”

“No, sir. I received the impression that it was not Miss Pendlebury’s intention to return. She was a little upset, sir, and expressed a desire to go to her studio and rest.”

“Upset? What about?”

“The accident, sir.”

I didn’t actually clutch the brow, but I did a bit of mental brow-clutching, as it were.

“Don’t tell me she had an accident!”

“Yes, sir.

“What sort of accident?”

“Automobile, sir.”

“Was she hurt?”

“No, sir. Only the gentleman.”

“What gentleman?”

“Miss Pendlebury had the misfortune to run over a gentleman in her car almost immediately opposite this building. He sustained a slight fracture of the leg.”

“Too bad! But Miss Pendlebury is all right?”

“Physically, sir, her condition appeared to be satisfactory. She was suffering a certain distress of mind.”

“Of course, with her beautiful, sympathetic nature. Naturally it’s a hard world for a girl, Jeeves, with fellows flinging themselves under the wheels of her car in one long, unending stream. It must have been a great shock to her. What became of the chump?”

“The gentleman, sir?”

“Yes.”

“He is in your spare bedroom, sir.”

“What!”

“Yes, sir.”

“In my spare bedroom?”

“Yes, sir. It was Miss Pendlebury’s desire that he should be taken there. She instructed me to telegraph to the gentleman’s sister, sir, who is in Paris, advising her of the accident. I also summoned a medical man, who gave it as his opinion that the patient should remain for the time being in statu quo.”

“You mean the corpse is on the premises for an indefinite visit?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Jeeves, this is a bit thick!”

“Yes, sir.”

And I meant it, dash it. I mean to say, a girl can be pretty heftily divine and ensnare the heart and what not, but she’s no right to turn a fellow’s flat into a Morgue. I’m bound to say that for a moment the Wooster passion ebbed a trifle.

“Well, I suppose I’d better go and introduce myself to the blighter. After all, I am his host. Has he a name?

“Mr. Pim, sir.”

“Pim!”

“Yes, sir. And the young lady addressed him as Lucius. It was owing to the fact that he was on his way here to examine the portrait which she had painted that Mr. Pim happened to be in the roadway at the moment when Miss Pendlebury turned the corner.”

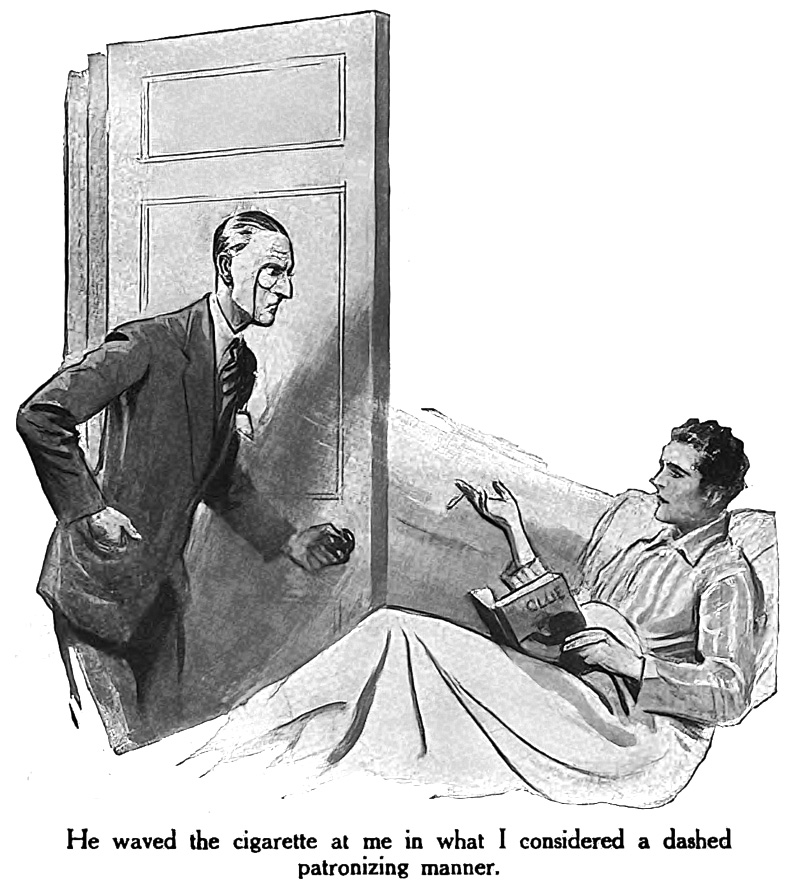

I HEADED for the spare bedroom. I was perturbed to a degree. I don’t know if you have ever loved and been handicapped in your wooing by a wavy-haired rival, but one of the things you don’t want in such circs is the rival parking himself on the premises with a broken leg. Apart from anything else, the advantage the position gives him is obviously terrific. There he is, sitting up and toying with a grape and looking pale and interesting, the object of the girl’s pity and concern, and where do you get off bounding about the place in morning costume and spats and with the rude flush of health on the cheek? It seemed to me that things were beginning to look pretty scaly.

I found Lucius Pim lying in bed, draped in a suit of my pyjamas, smoking one of my cigarettes, and reading a detective story. He waved the cigarette at me in what I considered a dashed patronizing manner.

“Ah, Wooster!” he said.

“Not so much of the ‘Ah, Wooster!’ ” I replied brusquely. “How soon can you be moved?”

“In a week or so, I fancy.”

“In a week!”

“Or so. For the moment, the doctor insists on perfect quiet and repose. So forgive me, old man, for asking you not to raise your voice. A hushed whisper is the stuff to give the troops. And now, Wooster, about this accident. We must come to an understanding.”

“Are you sure you can’t be moved?”

“Quite. The doctor said so.”

“I think we ought to get a second opinion.”

“Useless, my dear fellow. He was most emphatic, and evidently a man who knew his job. Don’t worry about my not being comfortable here. I shall be quite all right. I like this bed. And now, to return to the subject of this accident. My sister will be arriving to-morrow. She will be greatly upset. I am her favourite brother.”

“You are?”

“I am.”

“How many of you are there?”

“Six.”

“And you’re her favourite?”

“I am.”

It seemed to me that the other five must be pretty fairly sub-human, but I didn’t say so. We Woosters can curb the tongue.

“She married a bird named Slingby. Slingsby’s Superb Soups. He rolls in money. But do you think I can get him to lend a trifle from time to time to a needy brother-in-law?” said Lucius Pim bitterly. “No, sir! However, that is neither here nor there. The point is that my sister loves me devotedly; and, this being the case, she might try to prosecute and persecute and generally bite pieces out of poor little Gwladys if she knew that it was she who was driving the car that laid me out. She must never know, Wooster. I appeal to you as a man of honour to keep your mouth shut.”

“Naturally.”

“I’m glad you grasp the point so readily, Wooster. You are not the fool people take you for.”

“Who takes me for a fool?”

The Pim raised his eyebrows slightly.

“Don’t people?” he said. “Well, well. Anyway, that’s settled. Unless I can think of something better, I shall tell my sister that I was knocked down by a car which drove on without stopping and I didn’t get its number. And now perhaps you had better leave me. The doctor made a point of quiet and repose. Moreover, I want to go on with this story. The villain has just dropped a cobra down the heroine’s chimney, and I must be at her side. I’ll ring if I want anything.”

I headed for the sitting room. I found Jeeves there, staring at the portrait in rather a marked manner, as if it hurt him.

“Jeeves,” I said, “Mr. Pim appears to be a fixture.”

“Yes, sir.”

“For the nonce, at any rate. And to-morrow we shall have his sister, Mrs. Slingsby, of Slingsby’s Superb Soups, in our midst.”

“Yes, sir. I telegraphed to Mrs. Slingsby shortly before four. Assuming her to have been at her hotel in Paris at the moment of the telegram’s delivery, she will no doubt take a boat early to-morrow afternoon, reaching Dover—or, should she prefer the alternative route, Folkestone—in time to begin the railway journey at an hour which will enable her to arrive in London at about seven. She will possibly proceed first to her London residence . . .”

“Yes, Jeeves,” I said, “yes. A gripping story, full of action and human interest. You must have it set to music some time and sing it. Meanwhile, get this into your head. It is imperative that Mrs. Slingsby does not learn that it was Miss Pendlebury who broke her brother in two places. I shall require you, therefore, to approach Mr. Pim before she arrives, ascertain exactly what tale he intends to tell, and be prepared to back it up in every particular.”

“Very good, sir.”

“And now, Jeeves, what of Miss Pendlebury?”

“Sir?”

“She’s sure to call to make inquiries.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, she mustn’t find me here. You know all about women, Jeeves?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then tell me this. Am I not right in supposing that if Miss Pendlebury is in a position to go into the sick-room, take a long look at the interesting invalid, and then pop out, with the memory of that look fresh in her mind, and get a square sight of me lounging about in sponge-bag trousers, she will draw damaging comparisons? You see what I mean? Look on this picture and on that—the one romantic, the other not. . . . Eh?”

“Very true, sir. It is a point which I had intended to bring to your attention. An invalid undoubtedly exercises a powerful appeal to the motherliness which exists in every woman’s heart, sir. Invalids seem to stir their deepest feelings. The poet Scott has put the matter neatly in the lines—‘O Woman! in our hours of ease, uncertain, coy, and hard to please, When pain and anguish wring the brow——’ ”

I held up a hand.

“At some other time, Jeeves,” I said, “I shall be delighted to hear your piece, but just now I am not in the mood. The position being as I have outlined, I propose to clear out early to-morrow morning and not to reappear until nightfall. I shall take the car and dash down to Brighton for the day.”

“Very good, sir.”

“It is better so, is it not, Jeeves?”

“Indubitably, sir.”

“I think so, too. The sea breezes will tone up my system, which sadly needs a dollop of toning. I leave you in charge of the old home.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Convey my regrets and sympathy to Miss Pendlebury and tell her I have been called away on business.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Should the Slingsby require refreshment, feed her in moderation.”

“Very good, sir.”

“And, in poisoning Mr. Pim’s soup, don’t use arsenic, which is readily detected. Go to a good chemist and get something that leaves no traces.”

I sighed, and cocked an eye at the portrait.

“All this is very wonky, Jeeves.”

“Yes, sir.”

“When that portrait was painted, I was a happy man.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ah, well, Jeeves!”

“Very true, sir.”

And we left it at that.

IT was lateish when I got back on the following evening. What with a bit of ozone-sniffing, a good dinner, and a nice run home in the moonlight with the old car going as sweet as a nut, I was feeling in pretty good shape once more. In fact, coming through Purley, I went so far as to sing a trifle. The spirit of the Woosters is a buoyant spirit, and optimism had begun to reign again in the W. bosom.

The way I looked at it was, I saw I had been mistaken in assuming that a girl must necessarily love a fellow just because he has a broken leg. At first, no doubt, Gwladys Pendlebury would feel strangely drawn to the Pim when she saw him lying there a more or less total loss. But it would not be long before other reflections crept in. She would ask herself if she were wise in trusting her life’s happiness to a man who hadn’t enough sense to leap out of the way when he saw a car coming. She would tell herself that, if this sort of thing had happened once, who knew that it might not go on happening again and again all down the long years? And she would recoil from a married life which consisted entirely of going to hospitals and taking her husband fruit. She would realize how much better off she would be teamed up with a fellow like Bertram Wooster, who, whatever his faults, at least walked on the pavement and looked up and down a street before he crossed it.

It was in excellent spirits, accordingly, that I put the car in the garage, and it was with a merry Tra-la on my lips that I let myself into the flat as Big Ben began to strike eleven. I rang the bell, and presently, as if he had divined my wishes, Jeeves came in with siphon and decanter.

“Home again, Jeeves,” I said, mixing a spot.

“Yes, sir.”

“What has been happening in my absence? Did Miss Pendlebury call?”

“Yes, sir. At about two o’clock.”

“And left?”

“At about six, sir.”

I didn’t like this so much. A four-hour visit struck me as a bit sinister. However, there was nothing to be done about it.

“And Mrs. Slingsby?”

“She arrived shortly after eight and left at ten, sir.”

“Ah? Agitated?”

“Yes, sir. Particularly when she left. She was very desirous of seeing you, sir.”

“Seeing me?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Wanted to thank me brokenly, I suppose, for so courteously allowing her favourite brother a place to have his game legs in, eh?”

“Possibly, sir. On the other hand, she alluded to you in terms suggestive of disapprobation, sir.”

“She—what?”

“ ‘Feckless idiot’ was one of the expressions she employed, sir.”

“Feckless idiot?”

“Yes, sir.”

I couldn’t make it out. I simply couldn’t see what the woman had based her judgment on. My Aunt Agatha has frequently said that sort of thing about me, but she has known me from a boy.

“I must look into this, Jeeves. Is Mr. Pim asleep?”

“No, sir. He rang the bell a moment ago to inquire if we had not a better brand of cigarette in the flat.”

“He did, did he?”

“Yes, sir.”

“The accident doesn’t seem to have affected his nerve.”

“No, sir.”

I FOUND Lucius Pim sitting propped up among the pillows, reading his detective story.

“Ah, Wooster,” he said, “Welcome home. I say, in case you were worrying, it’s all right about that cobra. The hero had got at it without the villain’s knowledge and extracted its poison-fangs. With the result that when it fell down the chimney and started trying to bite the heroine its efforts were null and void. I doubt if a cobra has ever felt so silly.”

“Never mind about cobras.”

“It’s no good saying, ‘Never mind about cobras,’ ” said Lucius Pim in a gentle, rebuking sort of voice. “You’ve jolly well got to mind about cobras, if they haven’t had their poison-fangs extracted. Ask anyone. By the way, my sister looked in. She wants to have a word with you.”

“And I want to have a word with her.”

“Two minds with but a single thought. What she wants to talk to you about is this accident of mine. You remember that story I was to tell her? About the car driving on? Well, the understanding was, if you recollect, that I was only to tell it if I couldn’t think of something better. Fortunately, I thought of something much better. It came to me in a flash as I lay in bed looking at the ceiling. You see, that driving on story was thin. People don’t knock fellows down and break their legs and go driving on. The thing wouldn’t have held water for a minute. So I told her you did it.”

“What!”

“I said it was you who did it in your car. Much more likely. Makes the whole thing neat and well-rounded. I knew you would approve. At all costs we have got to keep it from her that I was outed by Gwladys. I made it as easy for you as I could, saying that you were a bit pickled at the time and so not to be blamed for what you did. Some fellows wouldn’t have thought of that. Still,” said Lucius Pim with a sigh, “I’m afraid she’s not any too pleased with you.”

“She isn’t, isn’t she?”

“No, she is not. And I strongly recommend you, if you want anything like a pleasant interview to-morrow, to sweeten her a bit overnight.”

“How do you mean, sweeten her?”

“I’d suggest you sent her some flowers. It would be a graceful gesture. Roses are her favourites. Shoot her in a few roses—Number Fifty, Hill Street, is the address—and it may make all the difference. I think it my duty to inform you, old man, that my sister Beatrice is rather a tough egg when roused. My brother-in-law is due back from New York at any moment, and the danger, as I see it, is that Beatrice, unless sweetened, will get at him and make him bring actions against you for torts and malfeasances and what not and get thumping damages. He isn’t over-fond of me and, left to himself, would rather approve than otherwise of people who broke my legs; but he’s crazy about Beatrice and will do anything she asks him to. So my advice is, Gather ye rose-buds while ye may and bung them in to Number Fifty, Hill Street. Otherwise, the case of Slingsby v. Wooster will be on the calendar before you can say What-ho.”

I gave the fellow a look. Lost on him, of course.

“It’s a pity you didn’t think of all that before,” I said. And it wasn’t so much the actual words, if you know what I mean, as the way I said it.

“I thought of it all right,” said Lucius Pim. “But as we were both agreed that at all costs——”

“Oh, all right,” I said. “All right, all right.”

“You aren’t annoyed?” said Lucius Pim, looking at me with a touch of surprise.

“Oh, no!”

“Splendid,” said Lucius Pim, relieved. “I knew you would feel that I had done the only possible thing. It would have been awful if Beatrice had found out about Gwladys. I dare say you have noticed, Wooster, that when women find themselves in a position to take a running kick at one of their own sex they are twice as rough on her as they would be on a man. Now, you, being of the male persuasion, will find everything made nice and smooth for you. A quart of assorted roses, a few smiles, a tactful word or two, and she’ll have melted before you know where you are. Play your cards properly, and you and Beatrice will be laughing merrily and playing Round and Round the Mulberry Bush together in about five minutes. Better not let Slingsby’s Soups catch you at it, however. He’s very jealous where Beatrice is concerned. And now you’ll forgive me, old chap, if I send you away. The doctor says I ought not to talk too much for a day or two. Besides, it’s time for beddy-bye.”

The more I thought it over, the better that idea of sending those roses looked. Lucius Pim was not a man I was fond of—in fact, if I had had to choose between him and a cockroach as a companion for a walking-tour, the cockroach would have had it by a short head—but there was no doubt that he had outlined the right policy. His advice was good, and I decided to follow it. Rising next morning at ten-fifteen, I swallowed a strengthening breakfast and legged it off to that flower-shop in Piccadilly. I couldn’t leave the thing to Jeeves. It was essentially a mission that demanded the personal touch. I laid out a couple of quid on a sizeable bouquet, sent it with my card to Hill Street, and then looked in at the Drones for a brief refresher. It is a thing I don’t often do in the morning, but this threatened to be rather a special morning.

It was about noon when I got back to the flat. I went into the sitting-room and tried to adjust the mind to the coming interview. It had to be faced, of course, but it wasn’t any good my telling myself that it was going to be one of those jolly scenes the memory of which cheers you up as you sit toasting your toes at the fire in your old age. I stood or fell by the roses. If they sweetened the Slingsby, all would be well. If they failed to sweeten her, Bertram was undoubtedly for it.

The clock ticked on, but she did not come. A late riser, I took it, and was slightly encouraged by the reflection. My experience of women has been that the earlier they leave the hay the more vicious specimens they are apt to be. My Aunt Agatha, for instance, is always up with the lark, and look at her.

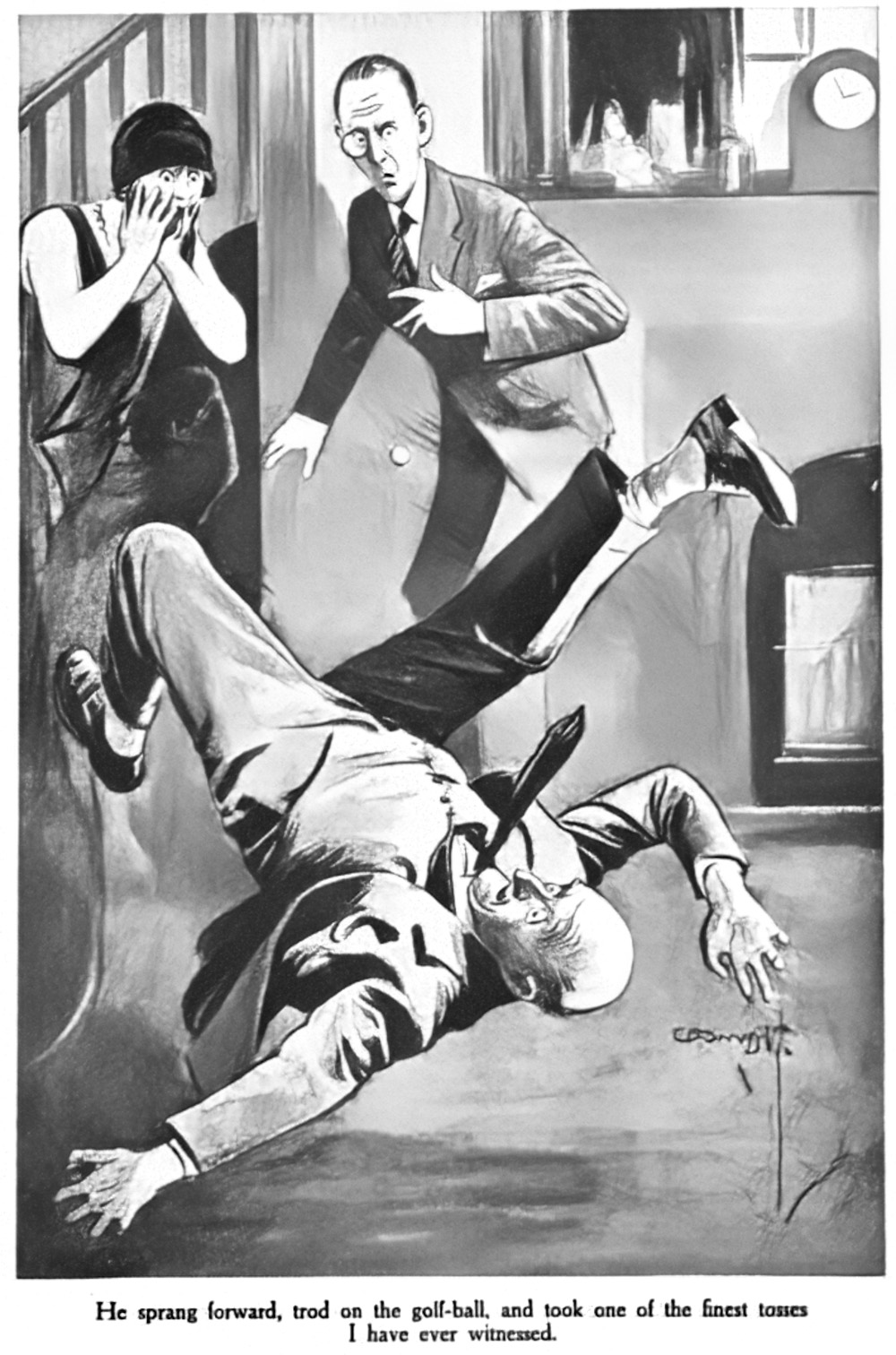

Still, you couldn’t be sure that this rule always worked, and after awhile the suspense began to get in amongst me a bit. To divert the mind, I fetched the old putter out of its bag and began to practise putts into a glass. After all, even if the Slingsby turned out to be all that I had pictured her in my gloomier moments, I should have improved my close-to-the-hole work on the green and be that much up, at any rate.

It was while I was shaping for a rather tricky shot that the front-door bell went.

I PICKED up the glass and shoved the putter behind the settee. It struck me that, if the woman found me engaged on what you might call a frivolous pursuit, she might take it to indicate lack of remorse and proper feeling. I straightened the collar, pulled down the waistcoat, and managed to fasten on the face a sort of sad half-smile which was welcoming without being actually jovial. It looked all right in the mirror, and I held it as the door opened.

“Mr. Slingsby,” announced Jeeves.

And, having spoken these words, he closed the door and left us alone together.

For quite a time there wasn’t anything in the way of chit-chat. The shock of expecting Mrs. Slingsby and finding myself confronted by something entirely different—in fact, not the same thing at all—seemed to have affected the vocal cords. And the visitor didn’t appear to be disposed to make light conversation himself. He stood there looking strong and silent. I suppose you have to be like that if you want to manufacture anything in the nature of a really convincing soup.

Slingsby’s Superb Soups was a Roman Emperor-looking sort of bird, with keen, penetrating eyes and one of those jutting chins. The eyes seemed to me to be fixed on me in a dashed unpleasant stare, and, unless I was mistaken, he was grinding his teeth a trifle. For some reason he appeared to have taken a strong dislike to me at sight, and I’m bound to say this rather puzzled me. I don’t pretend to have one of those fascinating personalities which you get from studying the booklets advertised in the back pages of the magazines, but I couldn’t recall another case in the whole of my career where a single glimpse of the old map had been enough to make anyone look as if he wanted to foam at the mouth. Usually, when people meet me for the first time, they don’t seem to know I’m there.

However, I exerted myself to play the host.

“Mr. Slingsby?”

“That is my name.”

“Just got back from America?”

“I landed this morning.”

“Sooner than you were expected, what?”

“So I imagine.”

“Very glad to see you.”

“You will not be long.”

I took time off to do a bit of gulping. I saw now what had happened. This bloke had been home, seen his wife, heard the story of the accident, and had hastened round to the flat to slip it across me. Evidently those roses had not sweetened the female of the species. The only thing to do now seemed to be to take a stab at sweetening the male.

“Have a drink?” I said.

“No!”

“A cigarette?”

“No!”

“A chair?”

“No!”

I went into the silence once more. These non-drinking, non-smoking non-sitters are hard birds to handle.

“Don’t grin at me, sir!”

I shot a glance at myself in the mirror, and saw what he meant. The sad half-smile had slopped over a bit. I adjusted it, and there was another pause.

“Now, sir,” said the Superb Souper. “To business. I think I need scarcely tell you why I am here.”

“No. Of course. Absolutely. It’s about that little matter——”

He gave a snort which nearly upset a vase on the mantelpiece.

“Little matter? So you consider it a little matter, do you?”

“Well——”

“Let me tell you, sir, that when I find that during my absence from the country a man has been annoying my wife with his importunities I regard it as anything but a little matter. And I shall endeavour,” said the Souper, the eyes gleaming a trifle brighter as he rubbed his hands together in a hideous, menacing way, “to make you see the thing in the same light.”

I couldn’t make head or tail of this. I simply couldn’t follow him. The lemon began to swim.

“Eh?” I said. “Your wife?”

“You heard me.”

“There must be some mistake.”

“There is. You made it.”

“But I don’t know your wife.”

“Ha!”

“I’ve never even met her.”

“Tchah!”

“Honestly, I haven’t.”

“Bah!”

He drank me in for a moment.

“Do you deny you sent her flowers?”

I felt the heart turn a double somersault. I began to catch his drift.

“Flowers!” he proceeded. “Roses, sir. Great, fat, beastly roses. Enough of them to sink a ship. Your card——”

His voice died away in a sort of gurgle, and I saw that he was staring at something behind me. I spun round, and there, in the doorway—I hadn’t seen it open, because during the last spasm of dialogue I had been backing cautiously towards it—there in the doorway stood a female. One glance was enough to tell me who she was. No woman could look so like Lucius Pim who hadn’t the misfortune to be related to him. It was Sister Beatrice, the tough egg. I saw all. She had left her home before the flowers arrived; she had sneaked, unsweetened, into the flat while I was fortifying the system at the Drones; and here she was.

“Er——” I said.

“Alexander!” said the female.

‘‘Goo!” said the Souper. Or it may have been “Coo!”

Whatever it was, it was in the nature of a battle-cry or slogan of war. The Souper’s worst suspicions had obviously been confirmed. His eyes shone with a strange light. His chin pushed itself out couple of inches. He clenched and unclenched his fingers once or twice, as if to make sure that they were working properly and could be relied on to do a good, clean job of strangling. Then, once more observing “Coo!” (or “Goo!”) he sprang forward, trod on the golf-ball I had been practising putting with, and took one of the finest tosses I have ever witnessed. The purler of a lifetime. For a moment the air seemed to be full of arms and legs, and then, with a thud that nearly dislocated the flat, he made a forced landing against the wall.

AND, feeling I had had about all I wanted, I oiled from the room and was in the act of grabbing my hat from the rack in the hall when Jeeves appeared.

“I fancied I heard a noise, sir,” said Jeeves.

“Quite possibly,” I said. “It was Mr. Slingsby.”

“Sir?”

“Mr. Slingsby practising Russian dances,” I explained. “I rather think he has fractured an assortment of limbs. Better go in and see.”

“Very good, sir.”

“If he is the wreck I imagine, put him in my room and send for a doctor. The flat is filling up nicely with the various units of the Pim family and its connections, eh, Jeeves?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I think the supply is about exhausted, but should any aunts or uncles by marriage come along and break their limbs, bed them out on the Chesterfield.”

“Very good, sir.”

“I, personally, Jeeves,” I said, opening the front door and pausing on the threshold, “am off to Paris. I will wire you the address. Notify me in due course when the place is free from Pims and completely purged of Slingsbys, and I will return. Oh, and, Jeeves.”

“Sir?”

“Spare no effort to mollify these birds. They think—at least, Slingsby (female) thinks, and what she thinks to-day he will think to-morrow—that it was I who ran over Mr. Pim in my car. Endeavour during my absence to sweeten them.”

“Very good, sir.”

“And now perhaps you had better be going in and viewing the body. I shall proceed to the Drones, where I shall lunch, subsequently catching the afternoon train at Victoria. Meet me there with an assortment of luggage.”

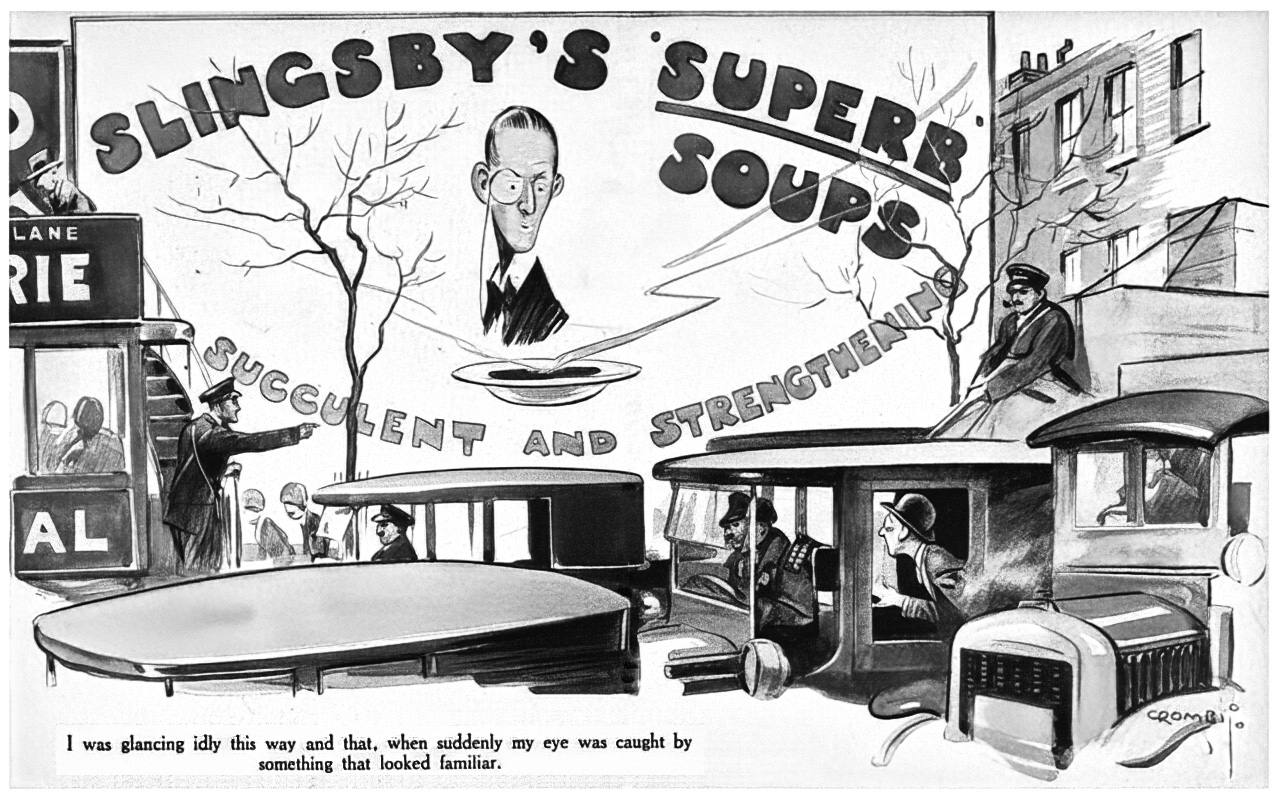

IT was a matter of three weeks or so before Jeeves sent me the “All clear” signal. I spent the time pottering pretty perturbedly about Paris and environs. It is a city I am fairly fond of, but I was glad to be able to return to the old home. I hopped on to a passing aeroplane and a couple of hours later was bowling through Croydon on my way to the centre of things. It was somewhere down in the Sloane Square neighbourhood that I first caught sight of the posters.

A traffic block had occurred, and I was glancing idly this way and that, when suddenly my eye was caught by something that looked familiar. And then I saw what it was.

Pasted on a blank wall and measuring about a hundred feet each way was an enormous poster, mostly red and blue. At the top of it were the words:—

SLINGSBY’S SUPERB SOUPS

and at the bottom:—

SUCCULENT AND STRENGTHENING

And, in between, me. Yes, dash it, Bertram Wooster in person. A reproduction of the Pendlebury portrait, perfect in every detail.

It was the sort of thing to make a fellow’s eyes flicker, and mine flickered. You might say a mist seemed to roll before them. Then it lifted, and I was able to get a good long look before the traffic moved on.

Of all the absolutely foul sights I have ever seen, this took the biscuit with ridiculous ease. The thing was a bally libel on the Wooster face, and yet it was as unmistakable as if it had had my name under it. I saw now what Jeeves had meant when he said that the portrait had given me a hungry look. In the poster this look had become one of bestial greed. There I sat, absolutely slavering, through a monocle about six inches in circumference, at a plateful of soup, looking as if I hadn’t had a meal for weeks. The whole thing seemed to take one straight away into a different and a dreadful world.

I woke from a species of trance or coma to find myself at the door of the block of flats.

Jeeves came shimmering down the hall, the respectful beam of welcome on the face.

“I am glad to see you back, sir.”

“Never mind about that,” I yipped. “What about——?”

“The posters, sir? I was wondering if you might have observed them.”

“I observed them!”

“Striking, sir?”

“Very striking. Now, perhaps you’ll kindly explain——”

“You instructed me, if you recollect, sir, to spare no effort to mollify Mr. Slingsby.”

“Yes, but——”

“It proved a somewhat difficult task, sir. For some time Mr. Slingsby, on the advice and owing to the persuasion of Mrs. Slingsby, appeared to be resolved to institute an action in law—a procedure which I knew you would find most distasteful.”

“Yes, but——”

“And then, the first day he was able to leave his bed, he observed the portrait, and it seemed to me judicious to point out to him its possibilities as an advertising medium. He readily fell in with the suggestion, and on my assurance that, should he abandon the projected action in law, you would willingly permit the use of the portrait, he entered into negotiations with Miss Pendlebury.”

“Oh? Well, I hope she’s got something out of it, at any rate.”

“Yes, sir. Mr. Pim, acting as Miss Pendlebury’s agent, drove, I understand, an extremely satisfactory bargain.”

“He acted as her agent, eh?”

“Yes, sir. In his capacity as fiancé to the young lady, sir.”

“Fiancé!”

“Yes, sir.”

IT shows how the sight of that poster had got into my ribs when I state that, instead of being laid out cold by this announcement, I merely said “Ha!” or “Ho!” or it may have been “H’m!”

“After that poster, Jeeves,” I said, “nothing seems to matter.”

“No, sir?”

“No, Jeeves. A woman has tossed my heart lightly away, but what of it?”

“Exactly, sir.”

“The voice of Love seemed to call to me, but it was a wrong number. Is that going to crush me?”

“No, sir.”

“No, Jeeves. It is not. But what does matter is this ghastly business of my face being spread from end to end of the metropolis with the eyes fixed on a plate of Slingsby’s Superb Soup. I must leave London. The Drones will kid me without ceasing.”

“Yes, sir. And Mrs. Spenser Gregson——”

I paled visibly. I hadn’t thought of Aunt Agatha and what she might have to say about letting down the family prestige.

“You don’t mean she has been ringing up?”

“Several times daily, sir.”

“Jeeves, flight is the only resource.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Back to Paris, what?”

“I should not recommend the move, sir. The posters are, I understand, shortly to appear in that city also. Advertising the Bouillon Suprême. Mr. Slingsby’s products command a large sale in France. The sight would be painful for you, sir.”

“Then where?”

“If I might make a suggestion, sir, why not adhere to your original intention of cruising in Mrs. Travers’s yacht in the Mediterranean? On the yacht you would be free from these advertising displays.”

The man seemed to me to be drivelling.

“But the yacht started weeks ago. It may be anywhere by now.”

“No, sir. The cruise was postponed for a month owing to the illness of Mrs. Travers’s chef, Anatole, who contracted influenza. Mrs. Travers refused to sail without him.”

“You mean they haven’t started?”

“Not yet, sir. The yacht sails from Southampton on Tuesday next.”

“Why, dash it, nothing could be sweeter.”

“No, sir.”

“Ring up Aunt Dahlia and tell her we’ll be there.”

“I ventured to take the liberty of doing that a few moments before you arrived, sir.”

“You did?”

“Yes, sir. I thought it probable that the plan would appeal to you.”

“It does! I’ve wished all along I was going on that cruise.”

“I, too, sir.”

“The tang of the salt breezes, Jeeves!”

“Yes, sir.”

“The moonlight on the water!”

“Precisely, sir.”

“The gentle heaving of the waves!”

“Exactly, sir.”

I felt absolutely in the pink. Gwladys—pah! The posters—bah! That was the way I looked at it.

“Yo-ho-ho, Jeeves!” I said.

“Yes, sir.”

“In fact, I will go further. Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!”

“Very good, sir. I will bring it immediately.”

Notes:

Annotations to the version of this story as collected in Very Good, Jeeves are on this site.

Printer’s error corrected above:

Magazine, p. 532a, had “infro’.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums