The Strand Magazine, August 1910

FTER five minutes of silent and intense thought, John Barton gave out the

statement that the moonlight on the terrace was pretty. Aline

Ellison said, “Yes, very pretty.”

FTER five minutes of silent and intense thought, John Barton gave out the

statement that the moonlight on the terrace was pretty. Aline

Ellison said, “Yes, very pretty.”

“But, I say, by Jove,” said the voice behind them, “you should see some of the moonlight effects on the Mediterranean, Barton. You really should. They would appeal to you. There is nothing like them, is there, Miss Ellison?”

Homicidal feelings surged up within John’s bosom. This was the fourth time that day that Lord Bertie Fendall had interrupted just as he got Aline alone. It was maddening. Man, in his dealings with the more attractive of the opposite sex, is either a buzzer or a thinker. John was a thinker. In ordinary circumstances a tolerable conversationalist, he became, when in the presence of Aline Ellison, a thinker of the most pronounced type, practically incapable of speech. What he wanted was time. He was not one of your rapid wooers, who meet a girl at dinner on Monday, give her their photograph on Tuesday morning, and propose on Tuesday afternoon. It took him a long while to get really started. He was luggage, not express. But he had perseverance, and, provided the line was kept clear, was bound to get somewhere in the end.

The advent of Lord Bertie had blocked the line. From the moment when Mr. Keith, their host, had returned from London bringing with him the son and heir of the Earl of Stockleigh, John’s manœuvres had received a check. Until then he had had Aline to himself, and all that had troubled him had been his inability to speak. He had gone dumbly round the links with her, rowed her silently on the lake, and sat by in mute admiration while she played waltz tunes after dinner. It had not been unmixed happiness, but at least there had been no competition. But in Lord Bertie he had a rival, and a rival who was a buzzer. Lord Bertie had the gift of conversation, and a course of travel had provided him with material for small-talk. Aline, her father being rich and her mother a sort of female Ulysses, had gone over much of the ground which Lord Bertie had covered; and the animation with which she exchanged views of European travel with him made John moist with agony. John was no fool, but he had never penetrated farther into the heart of the Continent than Paris; and in conversations dealing with the view from the summit of the Jungfrau, or the paintings of obscure Dagoes in Florentine picture-galleries, this handicapped him.

On the present occasion he accepted defeat with moody resignation. His opportunity had gone. The conversation was now dealing with Monte Carlo, and Lord Bertie had plainly come to stay. His high-pitched voice rattled on and on. Aline seemed absorbed.

With a muttered excuse John turned into the house. It was hard. To-morrow he was leaving for London owing to the sudden illness of his partner. True, he would be coming back in a week or so, but in that time the worst would probably have happened. He went to bed so dispirited that, stubbing his toe against a chair in the dark, he merely sighed.

As he paced the terrace after breakfast, waiting for the motor, Keggs, the Keiths’ butler, approached.

At the beginning of his visit Keggs had inspired John with an awe amounting at times to positive discomfort. John was a big, broad-shouldered young man, and his hands and feet were built to scale. But no hands and feet outside of a freak museum could have been one half as large as his seemed to be in the earlier days of his acquaintanceship with Keggs. He had suffered terribly under the butler’s dignified gaze, until one morning the latter, with the air of a high priest conferring with an underling on some point of ritual, had asked him whether, in his opinion, he would be doing rightly in putting his shirt on Mumblin’ Mose in a forthcoming handicap, as he had been advised to do by a metropolitan friend who claimed to be in the confidence of the trainer. John, recovering from the shock, answered in the affirmative; and a long and stately exchange of ideas on the subject of Current Form ensued. At dinner, a few days later, the butler, leaning over John to help him to sherry, murmured softly:—

“Romped ’ome, sir, thanking you, sir,” and from that moment had intimated by his manner that John might consider himself promoted to the rank of an equal and a friend.

“Excuse me, sir,” said the butler, “but Frederick, who ’as charge of your packing, desired me to ask you what arrangements you wished made with regard to the dog, sir.”

The animal in question was a beautiful bulldog, Reuben by name. John had brought him to the country at the special request of Aline, who had met him in London and fallen an instant victim to his rugged charms.

“The dog?” he said. “Oh, yes. Tell Frederick to put his leash on. Where is he?”

“Frederick, sir?”

“No, Reuben.”

“Gruffling at ’is lordship, sir,” said Keggs, tranquilly, as if he were naming some customary and recognized occupation for bulldogs.

“Gruffling at——? What!”

“ ’Is Lordship, sir, ’ave climbed a tree, and Reuben is at the foot, gruffling at ’im, very fierce.”

John stared.

“ ’Is lordship, sir,” continued Keggs, “ ’as always been uncommon afraid of dogs, from boy’ood up. I ’ad the honour to be employed has butler some years ago by ’is father, Lord Stockleigh, and was enabled at that time to observe Lord ’Erbert’s extreme aversion for animals of that description. ’Is huneasiness in the presence of even ’er ladyship’s toy Pomeranian was ’ighly marked and much commented on in the servants’ ’all.”

“So you had met Lord Herbert before?”

“I was butler at the Castle a matter of six years, sir.”

“Well,” said John, with some reluctance, “I suppose we must get him out of that tree. Fancy being afraid of old Reuben! Why, he wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

“ ’E ’ave took an uncommon dislike to ’is lordship, sir,” said Keggs.

“Where’s the tree?”

“At the lower hend of the terrace, sir. Beyond the nood statoo, sir.”

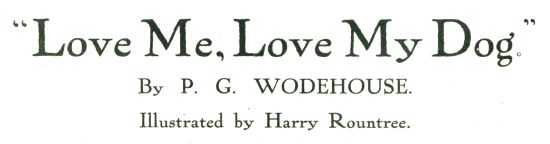

John ran in the direction indicated, his steps guided by an intermittent sound as of one gargling. Presently he came in view of the tree. At the foot, with his legs well spread and his massive head raised, stood Reuben. From a branch some little distance above the ground peered down the agitated face of Lord Bertie Fendall. His lordship’s aristocratic pallor was intensified. He looked almost green.

“I say,” he called, as John appeared, “do for Heaven’s sake take that beastly dog away. I’ve been up here the dickens of a time. It isn’t safe with that animal about. He’s a bally menace.”

Reuben glancing over his shoulder recognized his master, and, having no tail to speak of, wagged his body in a welcoming way. He looked up at Lord Bertie, and back again at John. As clearly as if he had spoken the words his eye said, “Come along, John. You and I are friends. Be a sportsman and pull him down out of that.”

“Take the brute away!” cried his lordship.

“He’s quite good-natured, really. He doesn’t mean anything. He won’t hurt you.”

“He won’t get the bally chance,” replied Lord Bertie, with acerbity. “Take him away.”

John stooped and grasped the dog’s collar.

“Come on, Reuben, you old fool,” he said. “We shall be missing that train.”

The motor was already at the door when he got back. Mr. Keith was there, and Aline.

“Too bad, Barton,” said Mr. Keith, “your having to break your visit like this. You’ll come back, though? How soon, do you think?”

“Inside of two weeks, I hope,” said John. “Hammond has had these influenza attacks before. They never last long. Have you seen Reuben’s leash anywhere?”

Aline Ellison uttered a cry of anguish.

“Oh, you aren’t taking Reuben, Mr. Barton! You can’t! You mustn’t! Mr. Keith, don’t let him. Come to auntie, Reuben, darling. Mr. Barton, if you take my precious Reuben away I’ll never speak to you again.”

John looked at her, and gulped.

He cleared his throat.

What he wanted to say was: “Miss Ellison, your lightest wish is law. I love you—not with the weak two-by-four imitation of affection such as may be offered to you by certain knock-kneed members of the Peerage, but with a great, broad, deep, throbbing love such as the world has never known. Take Reuben. You have my heart, my soul; shall I deny you a dog? Take Reuben. And when you look upon him, think, if but for a moment, of one who, though far away, is thinking, thinking always of you. Miss Ellison, good-bye!”

What he said was: “Er, I——”

And that, mind you, was pretty good going for John.

“Oh, thank you!” cried Aline. “Thank you so much, Mr. Barton. It’s perfectly sweet of you, and I’ll take such care of him. I won’t let him out of my sight for a minute.”

“. . .” said John, brightly.

Mathematicians among my readers do not need to be informed that “. . .” is the algebraical sign representing a blend of wheeze, croak, and hiccough.

And the motor rolled off.

It was about an hour later that Lord Bertie Fendall, finding Aline seated under the shade of the trees, came to a halt beside her.

“Barton went off in the car just now, didn’t he?” he inquired, casually.

“Yes,” said Aline.

Lord Bertie drew a deep breath of relief. At last he could walk abroad without the feeling that at any moment that infernal dog might charge out at him from round the next corner. With a light heart he dropped into a chair beside Aline, and began to buzz.

“Do you know, Miss Ellison——”

A short cough immediately behind him made him look round. His voice trailed off. His eyeglass fell with a jerk and bounded on the end of its cord. He sprang to his feet.

“Oh, there you are, Reuben,” said Aline. “Here, come here. What have you been doing to your nose? It’s all muddy. Aren’t you fond of dogs, Lord Herbert? I love them.”

“Eh? I beg your pardon?” said his lordship, revolving warily on his own axis, as the animal lumbered past him. “Oh, yes. Yes. That is to say—oh, yes. Very.”

Aline was removing the mud from Reuben’s nose with the corner of her pocket-handkerchief.

“Don’t you think you can generally tell a man’s character by whether dogs take to him or not? They have such wonderful instinct.”

“Wonderful,” agreed his lordship, meeting Reuben’s rolling eye and looking hastily away.

“Mr. Barton was going to take Reuben with him, but that would have been silly for such a short while, wouldn’t it?”

“Yes. Oh, yes,” said Lord Bertie. “I suppose,” he went on, “he will spend most of his time in the stables and so on, don’t you know? Not in the house, I mean, don’t you know, what?”

“The idea!” cried Aline, indignantly. “Reuben’s not a stable dog. I’m never going to let him out of my sight.”

“No?” said Lord Bertie a little feverishly. “No? Oh, no. Quite so.”

“There!” said Aline, giving Reuben a push. “Now you’re tidy. What were you saying, Lord Herbert?”

Reuben moved a step forward, and wheezed slightly.

“Excuse me, Miss Ellison,” said his lordship. “I’ve just recollected an important—there’s a good old boy!—an important letter I meant to have written. Excuse me!”

The announcement of his proposed departure may have been somewhat abrupt, but at any rate no fault could be found with his manner of leaving. It was ceremonious in the extreme. He moved out of her presence backwards, as if she had been royalty.

Aline saw him depart with a slightly aggrieved feeling. She had been in the mood for company. For some reason which she could not define she was conscious of quite a sensation of loneliness. It was absurd to think that John’s departure could have caused this. And yet somehow it did leave a blank. Perhaps it was because he was so big and silent. You grew used to his being there just as you grew used to the scenery, and you missed him when he was gone. That was all. If Nelson’s column were removed, one would feel lonely in Trafalgar Square.

Lord Bertie, meanwhile, having reached the smoking-room, where he proposed to brood over the situation with the assistance of a series of cigarettes, found Keggs there, arranging the morning papers on a side-table. He flung himself into an arm-chair, and, with a scowl at the butler’s back, struck a match.

“I ’ope your lordship is suffering no ill effects from the adventure?” said Keggs, finishing the disposal of the papers.

“What?” said Lord Bertie, coldly. He disliked Keggs.

“I was alluding to your lordship’s encounter with the dog Reuben this morning.”

Lord Bertie started.

“What do you mean?”

“I observed that your lordship ’ad climbed a tree to elude the animal.”

“You saw it?”

Keggs bowed.

“Then why the devil, you silly old idiot,” demanded his lordship explosively, “didn’t you come and take the brute away?”

It had been the practice in the old days, both of Lord Bertie and of his father, to address the butler in moments of agitation with a certain aristocratic vigour.

“I ’ardly liked to interfere, your lordship, beyond informing Mr. Barton. The animal being ’is.”

Lord Bertie flung his cigarette out of the window, and kicked a foot-stool. Keggs regarded these evidences of an overwrought soul sympathetically.

“I can appreciate your lordship’s hemotion,” he said, “knowin’ ’ow haverse to dogs your lordship ’as always been. It seems only yesterday,” he continued, reminiscently, “that your lordship, then a boy at Heton, ’ome for the ’olidays, handed me a package of Rough on Rats, and instructed me to poison ’er ladyship your mother’s toy Pomeranian with it.”

Lord Bertie started for the second time since he had entered the room. He screwed his eyeglass firmly into his eye, and looked keenly at the butler. Keggs’s face was expressionless. Lord Bertie coughed. He looked round at the door. It was closed.

“You didn’t do it,” he said.

“The ’onorarium which your lordship offered,” said the butler, deprecatingly, “was only six postage-stamps and a ’arf share in a white rat. I did not consider it hadequate in view of the undoubted riskiness of the proposed act.”

“You’d have done it if I had offered more?”

“That, your lordship, it is impossible to say after this lapse of time.”

The Earl of Stockleigh had at one time had the idea of attaching his son and heir to the Diplomatic Service. Lord Bertie’s next speech may supply some clue to his lordship’s reasons for abandoning that scheme.

“Keggs,” he said, leaning forward, “what will you take to poison that dashed dog, Reuben?”

The butler raised a hand in pained protest.

“Your lordship, really!”

“Ten pounds.”

“Your lordship!”

“Twenty.”

Keggs seemed to waver.

“I’ll give you twenty-five,” said his lordship.

Before the butler could reply, the door opened and Mr. Keith entered.

“The morning papers, sir,” said Keggs deferentially, and passed out of the room.

It was a few days later that he presented himself again before Lord Bertie. His lordship was in low spirits. He was not in love with Aline—he would have considered it rather bad form to be in love with anyone—but he found her possessed of attractions and wealth sufficient to qualify her for an alliance with a Stockleigh; and he had concentrated his mind, so far as it was capable of being concentrated on anything, upon bringing the alliance about. And up to a point everything had seemed to progress admirably. Then Reuben had come to the fore and wrecked the campaign. How could a fellow keep up an easy flow of conversation with one eye on a bally savage bulldog all the time? And the brute never left her. Wherever she went he went, lumbering along like a cart-horse with a nasty look out of the corner of his eye whenever a fellow came up and tried to say a word. The whole bally situation, decided his lordship, was getting dashed impossible, and if something didn’t happen to change it he would get out of the place and go off to Paris.

“Might I ’ave a word, your lordship?” said Keggs.

“Well?”

“I ’ave been thinking over your lordship’s offer——”

“Yes?” said Lord Bertie, eagerly.

“The method of eliminating the animal which your lordship indicated would ’ardly do, I fear. Awkward questions would be asked, and a public hexposé would inevitably ensue. If your lordship would permit me to make an alternative suggestion?”

“Well?”

“I was reading a article in the newspaper, your lordship, on ’ow sparrows and such is painted up to represent bullfinches, canaries, and so on, and I says to myself, ‘Why not?’ ”

“Why not what?” demanded his lordship, irritably.

“Why not substitoot for Reuben another dog painted to appear identically similar?”

His lordship looked fixedly at him.

“Do you know what you are, Keggs?” he said. “A blithering idiot.”

“Your lordship always ’ad a spirited manner of speech,” said Keggs, deprecatingly.

“You and your sparrows and canaries and bullfinches! Do you think Reuben’s a bally bird?”

“I see no flaw in the idea, your lordship. ’Orses and such is frequently treated that way. I was talking that matter over with Roberts, the chauffeur——”

“What! And how many more people have you discussed my affairs with?”

“Only Roberts, your lordship. It was unavoidable. Roberts being the owner of a dog which could be painted up to be the living spit of Reuben, your lordship.”

“What!”

“For a hadequate ’onorarium, your lordship.”

Lord Bertie’s manner became excited.

“Where is he? No, not Roberts. I don’t want to see Roberts. This dog, I mean.”

“At Roberts’s cottage, your lordship. ’E is a great favourite with the children.”

“Is he, by Jove? Good-tempered animal, eh?”

“Extremely so, your lordship.”

“Show him to me, then. There might be something in this.”

Keggs coughed.

“And the ’onorarium, your lordship?”

“Oh, that. Oh, I’ll remember Roberts all right.”

“I was not thinking exclusively of Roberts, your lordship.”

“Oh, I’ll remember you, too.”

“Thank you, your lordship. About ’ow extensively, your lordship?”

“I’ll see that you get a couple of pounds apiece. That’ll be all right.”

“I fear,” said Keggs, shaking his head, “hit could ’ardly be done hat the price. In a hearlier conversation your lordship mentioned twenty-five. That, ’owever, was for the comparatively simple task of poisoning the animal. The substitootion would be more expensive, owing to the nature of the process. I was thinking of a ’undred, your lordship.”

“Don’t be a fool, Keggs.”

“I fear Roberts could not be induced to do it for less, the process being expensive.”

“A hundred! No, it’s dashed absurd. I won’t do it.”

“Very good, your lordship.”

“Here stop. Don’t go. Look here, I’ll give you fifty.”

“I fear it could not be done, your lordship.”

“Sixty guineas. Seven——. Here, don’t go. Oh, very well then, a hundred.”

“I thank you, your lordship. If your lordship will be at the bend in the road in ’alf an hour’s time the animal will be there.”

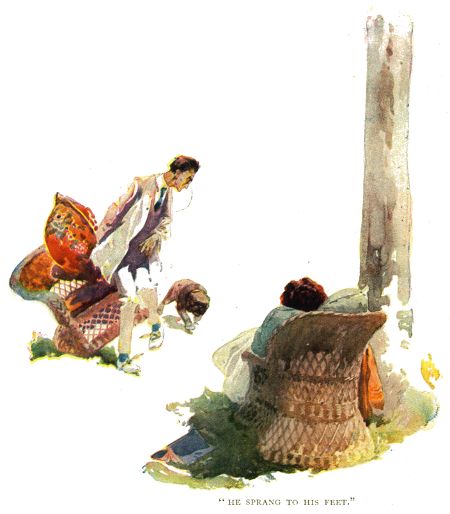

Lord Bertie was a little early at the tryst, but he had not been waiting long when a party of three turned the corner. One of the party was Keggs. The second he recognized as Roberts the chauffeur, a wooden-faced man who wore a permanent air of melancholy. The third, who waddled along at the end of a rope, was a dingy white bulldog.

The party came to a halt before him. Roberts touched his hat, and eyed the dog sadly. The dog sniffed at his lordship with apparent amiability. Keggs did the honours.

“The animal, your lordship.”

Lord Bertie put up his glass and inspected the exhibit.

“Eh?”

“The animal I mentioned, your lordship.”

“That?” said Lord Bertie. “Why, dash it all, that bally milk-coloured brute isn’t like Reuben.”

“Not at present, your lordship. But your lordship is forgetting the process. In two days Roberts will be able to treat that hanimal so that Reuben’s own mother would be deceived.”

Lord Bertie looked with interest at the artist. “No, really? Is that a fact?”

Roberts, an economist in speech, looked up, touched his hat again in a furtive manner, and fixed his eyes once more on the dog.

“Well, he seems friendly all right,” said Lord Bertie, as the animal endeavoured to lick his hand.

“He ’as the most placid disposition,” Keggs assured him. “A great improvement on Reuben, your lordship. Well worth the ’undred.”

Hope fought with scepticism in Lord Bertie’s mind during the days that followed. There were moments when the thing seemed possible, and moments when it seemed absurd. Of course, Keggs was a silly old fool, but, on the other hand, there were possibilities about Roberts. The chauffeur had struck his lordship as a capable-looking sort of man. And, after all, there were cases on record of horses being painted and substituted for others, so why not bulldogs?

It was absolutely necessary that some step be taken shortly. His jerky manner and abrupt retreats were getting on Aline’s nerves. He could see that.

“Look here, Keggs,” he said, on the third morning. “I can’t wait much longer. If you don’t bring on that dog soon, the whole thing’s off.”

“We ’ave already effected the change, your lordship. The delay ’as been due to the fact that Roberts wished to make an especial good job of it.”

“And has he?”

“That I will leave your lordship to decide. The hanimal is now asleep on the terrace.”

He led the way to where a brown heap lay in the sunshine. His lordship followed with some diffidence.

“An extraordinary likeness, your lordship.”

Lord Bertie put up his eyeglass.

“By Jove, I should say it was. Do you mean to tell me——?”

“If your lordship will step forward and prod the animal, your lordship will be convinced by the amiability——”

“Prod him yourself,” said Lord Bertie.

Keggs did so. The slumberer raised his head dreamily, and rolled over again. Lord Bertie was satisfied. He came forward and took a prod. With Reuben this would have led to a scene of extreme activity. The excellent substitute merely flopped back on his side again.

“By Jove! it’s wonderful,” he said.

“And if your lordship ’appens to have a cheque-book handy?”

“You’re in a bally hurry,” said Lord Bertie, complainingly.

“It’s Roberts, your lordship,” sighed Keggs. “ ’E is a poor man, and ’e ’as a wife and children.”

After lunch Aline was plaintive.

“I can’t make out,” she said, “what is the matter with Reuben. He doesn’t seem to care for me any more. He won’t come when I call. He wants to sleep all the time.”

“Oh, he’ll soon get used—I mean,” added Lord Bertie, hastily, “he’ll soon get over it. I expect he has been in the sun too much, don’t you know?”

The substitute’s lethargy continued during the rest of that day, but on the following morning after breakfast Lord Bertie observed him rolling along the terrace behind Aline. Presently the two settled themselves under the big sycamore tree, and his lordship sallied forth.

“And how is Reuben this morning?” he inquired, brightly.

“He’s not very well, poor old thing,” said Aline. “He was rather sick in the night.”

“No, by Jove; really?”

“I think he must have eaten something that disagreed with him. That’s why he was so quiet yesterday.”

Lord Bertie glanced sympathetically at the brown mass on the ground. How wary one should be of judging by looks. To all appearances that dog there was Reuben, his foe. But beneath that Reuben-like exterior beat the gentle heart of the milk-coloured substitute, with whom he was on terms of easy friendship.

“Poor old fellow!” he said.

He bent down and gave the animal’s ear a playful tweak. . . .

It was a simple action, an action from which one would hardly have expected anything in the nature of interesting by-products—yet it undoubtedly produced them. What exactly occurred Lord Bertie could not have said. There was a sort of explosion. The sleeping dog seemed to uncurl like a released watch-spring, and the air became full of a curious blend of sniff and snarl. An eminent general has said that the science of war lies in knowing when to fall back. Something, some instinct, seemed to tell Lord Bertie that the moment was ripe for falling back, and he did so over a chair.

He rose, with a scraped shin, to find Aline holding the dog’s collar with both hands, her face flushed with the combination of wrath and muscular effort.

“What did you do that for?” she demanded fiercely. “I told you he was ill.”

“I—I—I——” stammered his lordship.

The thing had been so sudden. The animal had gone off like a bomb.

“I—I——”

“Run!” she panted. “I can’t hold him. Run! Run!”

Lord Bertie cast one look at the bristling animal, and decided that her advice was good and should be followed.

He had reached the road before he slowed to a walk. Then, feeling safe, he was about to light a cigarette, when the match fell from his fingers and he stood gaping.

Round the bend of the road, from the direction of Robert’s cottage, there had appeared a large bulldog of a dingy-white colour.

Keggs, swathed in a green baize apron, was meditatively polishing Mr. Keith’s silver in his own private pantry, humming an air as he worked, when Frederick, the footman, came to him. Frederick was a supercilious young man, with long legs and a receding chin.

“Polishing the silver, old top?” he inquired, genially.

“In answer to your question, Frederick,” replied Keggs, with dignity, “I ham polishing the silver.”

Frederick, in his opinion, needed to be kept in his place.

“His nibs is asking for you,” said Frederick.

“You allude to——”

“Bertie,” said Frederick, definitely.

“If,” said Keggs, “Lord ’Erbert Fendall desires to see me, I will go to ’im at once.”

“Another bit of luck for ’Erbert,” said Frederick, cordially. “ ’E’s in the smoking-room.”

“Your lordship wished to see me?”

Lord Bertie, who was rubbing his shin reflectively with his back to the door, wheeled, and glared balefully at the saintly figure before him.

“You bally old swindler!” he cried.

“Your lordship!”

“Do you know I could have you sent to prison for obtaining money under false pretences?”

“Your lordship!”

“Don’t stand there pretending not to know what I mean.”

“If your lordship would explain, I ’ave no doubt——”

“Explain! By Jove, I’ll explain, if that’s what you want. What do you mean by doping Reuben and palming him off on me as another dog? Is that plain enough?”

“The words is intelligible,” conceded Keggs, “but the accusation is overwhelming.”

“You bally old rogue!”

“Your lordship,” said Keggs, soothingly, “ ’as been deceived, has I predicted, by the reely extraordinary likeness. Roberts ’as undoubtedly eclipsed ’imself.”

“Do you mean to tell me that dog is the one you showed me in the road? Then how do you account for this? I saw that milk-coloured brute of Roberts’s out walking only a moment ago.”

“Roberts ’as two, your lordship.”

“What?”

“The himage of one another, your lordship.”

“What?”

“Twins, your lordship,” added the butler, softly.

Lord Bertie upset a chair.

“Your lordship,” said Keggs, “if I may say so, ’as always from boy’ood up been a little too ’asty at jumping to conclusions. If your lordship will recollect, it was your lordship’s ’asty assertion as a boy that you ’ad seen me occupied in purloining ’is lordship your father’s port wine that led to my losing the excellent situation, which I might be still ’oldin’, of butler at Stockleigh Castle.”

Lord Bertie stared.

“Eh? What? So that——? I see!” he said. “By Jove, I see it all. You’ve been trying to get a bit of your own back. What?”

“Your lordship! I ’ave done nothing. ’Appily I can prove it.”

“Prove it?”

The butler bowed.

“The resemblance between the two animals is extraordinary, but not absolutely complete. Reuben ’as a full set of teeth, but Roberts’s dog ’as the last tooth but one at the back missing.”

He paused.

“If your lordship,” he added with the dignity that makes a good man, wronged, so impressive, “wishes to disprove my assertions, the modus hoperandi is puffectly simple. All your lordship ’as to do is to open the animal’s mouth and submit ’is back teeth to a pussonal hinspection.”

John Barton alighted from the motor, and, in answer to Keggs’s respectful inquiry, replied that he was quite well.

“Where is everybody?” he asked.

“Mr. Keith is out walking, sir. ’Is lordship ’as left. Miss——”

“Left!”

“ ’Is lordship was compelled to leave a few days back, sir, ’avin’ business in Paris.”

“Ah! Returning soon, I suppose?”

“On that point, sir, ’is lordship seemed somewhat uncertain.”

“How is Reuben?”

“Reuben ’ave enjoyed good ’ealth, sir. ’E is down by the lake, I fancy, sir, at the present moment, with Miss Ellison.”

“I think I might as well go and see him,” said John, awkwardly.

“I fancy ’e would appreciate it, sir.”

John turned away. The lake was some distance from the house. The nearer he got to it the more acute did his nervousness become. Once or twice after he had caught the gleam of Aline’s white dress through the trees he almost stopped, then forced himself on in a sort of desperation.

Aline was standing at the water’s edge encouraging Reuben to growl at a duck. Both suspended operations and turned to greet him, Reuben effusively, Aline with the rather absent composure which always deprived him of the power of speech.

“I’ve taken great care of Reuben, Mr. Barton,” she said.

Something neat and epigrammatic should have proceeded from John. It did not.

“I’d like to have you all for my own, wouldn’t I, Reuben?” she went on, bending over the snuffling dog, and kissing him fondly in the groove between his eyes.

It was a simple action, but it had a remarkable effect on John. Something inside him seemed suddenly to snap. In a moment he had become very cool and immensely determined. Conversation is a safety-valve. Deprive a man of the use of it for a long enough time, and he is liable to explode at any moment. It is the general idea that the cave-man’s first advance to the lady of his choice was a blow on the head with his club. This is not the case. He used the club because, after hanging round for a month or so trying to think of something to say, it seemed to him the only way of disclosing his affection. John was a lineal descendant of the cave-man. He could not use a club, for he had none. But he did the next best thing. Stooping swiftly, he seized Aline round the waist, picked her up, and kissed her.

She stood staring at him, her lips parted, her eyes slowly widening till they seemed to absorb the whole of her face. Reuben, with the air of a dramatic critic at an opening performance, sat down and awaited developments.

A minute before, John would have wilted beneath that stare. But now the spirit of the cave-man was strong in him. He seized her hands, and pulled her slowly towards him.

“You’re going to have us both,” he said.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums