The Strand, March 1922

THE blow fell at precisely one forty-five (summer time). Spenser, my Aunt Agatha’s butler, was offering me the fried potatoes at the moment, and such was my emotion that I lofted six of them on to the sideboard with the spoon. Shaken to the core, if you know what I mean.

I’ve told you how I got engaged to Honoria Glossop in my efforts to do young Bingo Little a good turn. Well, on this particular morning she had lugged me round to Aunt Agatha’s for lunch, and I was just saying “Death, where is thy jolly old sting?” when I realized that the worst was yet to come.

“Bertie,” she said, suddenly, as if she had just remembered it, “what is the name of that man of yours—your valet?”

“Eh? Oh, Jeeves.”

“I think he’s a bad influence for you,” said Honoria. “When we are married you must get rid of Jeeves.”

It was at this point that I jerked the spoon and sent six of the best and crispest sailing on to the sideboard, with Spenser gambolling after them like a dignified old retriever.

“Get rid of Jeeves!” I gasped.

“Yes. I don’t like him.”

“I don’t like him,” said Aunt Agatha.

“But I can’t. I mean—why, I couldn’t carry on for a day without Jeeves.”

“You will have to,” said Honoria. “I don’t like him at all.”

“I don’t like him at all,” said Aunt Agatha. “I never did.”

Ghastly, what? I’d always had an idea that marriage was a bit of a wash-out, but I’d never dreamed that it demanded such frightful sacrifices from a fellow. I passed the rest of the meal in a sort of stupor.

The scheme had been, if I remember, that after lunch I should go off and caddy for Honoria on a shopping tour down Regent Street; but when she got up and started collecting me and the rest of her things, Aunt Agatha stopped her.

“You run along, dear,” she said. “I want to say a few words to Bertie.”

So Honoria legged it, and Aunt Agatha drew up her chair and started in.

“Bertie,” she said, “dear Honoria does not know it, but a little difficulty has arisen about your marriage.”

“By Jove! not really?” I said, hope starting to dawn.

“Oh, it’s nothing at all, of course. It is only a little exasperating. The fact is, Sir Roderick is being rather troublesome.”

“Thinks I’m not a good bet? Wants to scratch the fixture? Well, perhaps he’s right.”

“Pray do not be so absurd, Bertie. It is nothing so serious as that. But the nature of Sir Roderick’s profession unfortunately makes him—over-cautious.”

I didn’t get it.

“Over-cautious?”

“Yes. I suppose it is inevitable. A nerve specialist with his extensive practice can hardly help taking a rather warped view of humanity.”

I got what she was driving at now. Sir Roderick Glossop, Honoria’s father, is always called a nerve specialist, because it sounds better, but everybody knows that he’s really a sort of janitor to the looney-bin. I mean to say, when your uncle the Duke begins to feel the strain a bit and you find him in the blue drawing-room sticking straws in his hair, old Glossop is the first person you send for. He toddles round, gives the patient the once-over, talks about over-excited nervous systems, and recommends complete rest and seclusion and all that sort of thing. Practically every posh family in the country has called him in at one time or another, and I suppose that, being in that position—I mean constantly having to sit on people’s heads while their nearest and dearest ’phone to the asylum to send round the wagon—does tend to make a chappie take what you might call a warped view of humanity.

“You mean he thinks I may be a looney, and he doesn’t want a looney son-in-law?” I said.

Aunt Agatha seemed rather peeved than otherwise at my ready intelligence.

“Of course, he does not think anything so ridiculous. I told you he was simply exceedingly cautious. He wants to satisfy himself that you are perfectly normal.” Here she paused, for Spenser had come in with the coffee. When he had gone, she went on: “He appears to have got hold of some extraordinary story about your having pushed his son Oswald into the lake at Ditteredge Hall. Incredible, of course. Even you would hardly do a thing like that.”

“Well, I did sort of lean against him, you know, and he shot off the bridge.”

“Oswald definitely accuses you of having pushed him into the water. That has disturbed Sir Roderick, and unfortunately it has caused him to make inquiries, and he has heard about your poor Uncle Henry.”

She eyed me with a good deal of solemnity, and I took a grave sip of coffee. We were peeping into the family cupboard and having a look at the good old skeleton. My late Uncle Henry, you see, was by way of being the blot on the Wooster escutcheon. An extremely decent chappie personally, and one who had always endeared himself to me by tipping me with considerable lavishness when I was at school; but there’s no doubt he did at times do rather rummy things, notably keeping eleven pet rabbits in his bedroom; and I suppose a purist might have considered him more or less off his onion. In fact, to be perfectly frank, he wound up his career, happy to the last and completely surrounded by rabbits, in some sort of a home.

“It is very absurd, of course,” continued Aunt Agatha. “If any of the family had inherited poor Henry’s eccentricity—and it was nothing more—it would have been Claude and Eustace, and there could not be two brighter boys.”

Claude and Eustace were twins, and had been kids at school with me in my last summer term. Casting my mind back, it seemed to me that “bright” just about described them. The whole of that term, as I remembered it, had been spent in getting them out of a series of frightful rows.

“Look how well they are doing at Oxford. Your Aunt Emily had a letter from Claude only the other day saying that they hoped to be elected shortly to a very important college club, called The Seekers.”

“Seekers?” I couldn’t recall any club of the name in my time at Oxford. “What do they seek?”

“Claude did not say. Truth or Knowledge, I should imagine. It is evidently a very desirable club to belong to, for Claude added that Lord Rainsby, the Earl of Datchet’s son, was one of his fellow-candidates. However, we are wandering from the point, which is that Sir Roderick wants to have a quiet talk with you quite alone. Now I rely on you, Bertie, to be—I won’t say intelligent, but at least sensible. Don’t giggle nervously: try to keep that horrible glassy expression out of your eyes: don’t yawn or fidget: and remember that Sir Roderick is the president of the West London branch of the anti-gambling league, so please do not talk about horse-racing. He will lunch with you at your flat to-morrow at one-thirty. Please remember that he drinks no wine, strongly disapproves of smoking, and can only eat the simplest food, owing to an impaired digestion. Do not offer him coffee, for he considers it the root of half the nerve-trouble in the world.”

“I should think a dog-biscuit and a glass of water would about meet the case, what?”

“Bertie!”

“Oh, all right. Merely persiflage.”

“Now it is precisely that sort of idiotic remark that would be calculated to arouse Sir Roderick’s worst suspicions. Do please try to refrain from any misguided flippancy when you are with him. He is a very serious-minded man. . . Are you going? Well, please remember all I have said. I rely on you, and, if anything goes wrong, I shall never forgive you.”

“Right ho!” I said.

And so home, with a jolly day to look forward to.

I BREAKFASTED pretty late next morning and went for a stroll afterwards. It seemed to me that anything I could do to clear the old lemon ought to be done, and a bit of fresh air generally relieves that rather foggy feeling that comes over a fellow early in the day. I had taken a stroll in the Park, and got back as far as Hyde Park Corner, when some blighter sloshed me between the shoulder-blades. It was young Eustace, my cousin. He was arm-in-arm with two other fellows, the one on the outside being my cousin Claude and the one in the middle a pink-faced chappie with light hair and an apologetic sort of look.

“Bertie, old egg!” said young Eustace, affably.

“Hallo!” I said, not frightfully chirpily.

“Fancy running into you, the one man in London who can support us in the style we are accustomed to! By the way, you’ve never met old Dog-Face, have you? Dog-Face, this is my cousin Bertie. Lord Rainsby—Mr. Wooster. We’ve just been round to your flat, Bertie. Bitterly disappointed that you were out, but were hospitably entertained by old Jeeves. That man’s a corker, Bertie. Stick to him.”

“What are you doing in London?” I asked.

“Oh, buzzing round. We’re just up for the day. Flying visit, strictly unofficial. We oil back on the three-ten. And now, touching that lunch you very decently volunteered to stand us, which shall it. be? Ritz? Savoy? Carlton? Or, if you’re a member of Ciro’s or the Embassy, that would do just as well.”

“I can’t give you lunch. I’ve got an engagement myself. And, by Jove,” I said, taking a look at my watch, “I’m late.” I hailed a taxi. “Sorry.”

“As man to man, then,” said Eustace, “lend us a fiver.”

I hadn’t time to stop and argue. I unbelted the fiver and hopped into the cab. It was twenty to two when I got to the flat. I bounded into the sitting-room, but it was empty.

Jeeves shimmied in.

“Sir Roderick has not yet arrived, sir.”

“Good egg!” I said. “I thought I should find him smashing up the furniture.” My experience is that the less you want a fellow, the more punctual he’s bound to be, and I had had a vision of the old lad pacing the rug in my sitting-room, saying “He cometh not!” and generally hotting up. “Is everything in order?”

“I fancy you will find the arrangements quite satisfactory, sir.”

“What are you giving us?”

“Cold consommé, a cutlet, and a savoury, sir. With lemon-squash, iced.”

“Well, I don’t see how that can hurt him. Don’t go getting carried away by the excitement of the thing and start bringing in coffee.”

“No, sir.”

“And don’t let your eyes get glassy, because, if you do, you’re apt to find yourself in a padded cell before you know where you are.”

“Very good, sir.”

There was a ring at the bell.

“Stand by, Jeeves,” I said. “We’re off!”

I HAD met Sir Roderick Glossop before, of course, but only when I was with Honoria: and there is something about Honoria which makes almost anybody you meet in the same room seem sort of under-sized and trivial by comparison. I had never realized till this moment what an extraordinarily formidable old bird he was. He had a pair of shaggy eyebrows which gave his eyes a piercing look which was not at all the sort of thing a fellow wanted to encounter on an empty stomach. He was fairly tall and fairly broad, and he had the most enormous head, with practically no hair on it, which made it seem bigger and much more like the dome of St. Paul’s. I suppose he must have taken about a nine or something in hats. Shows what a rotten thing it is to let your brain develop too much.

“What ho! What ho! What ho!” I said, trying to strike the genial note, and then had a sudden feeling that that was just the sort of thing I had been warned not to say. Dashed difficult it is to start things going properly on an occasion like this. A fellow living in a London flat is so handicapped. I mean to say, if I had been the young squire greeting the visitor in the country, I could have said “Welcome to Meadowsweet Hall!” or something zippy like that. It sounds silly to say “Welcome to Number 6a, Crichton Mansions, Berkeley Street, W.”

“I am afraid I am a little late,” he said, as we sat down. “I was detained at my club by Lord Alastair Hungerford, the Duke of Ramfurline’s son. His Grace, he informed me, had exhibited a renewal of the symptoms which have been causing the family so much concern. I could not leave him immediately. Hence my unpunctuality, which I trust has not discommoded you.”

“Oh, not at all. So the Duke is off his rocker, what?”

“The expression which you use is not precisely the one I should have employed myself with reference to the head of perhaps the noblest family in England, but there is no doubt that cerebral excitement does, as you suggest, exist in no small degree.” He sighed as well as he could with his mouth full of cutlet. “A profession like mine is a great strain, a great strain.”

“Must be.”

“Sometimes I am appalled at what I see around me.” He stopped suddenly and sort of stiffened. “Do you keep a cat, Mr. Wooster?”

“Eh? What? Cat? No, no cat.”

“I was conscious of a distinct impression that I had heard a cat mewing either in the room or very near to where we are sitting.”

“Probably a taxi or something in the street.”

“I fear I do not follow you.”

“I mean to say, taxis squawk, you know. Rather like cats in a sort of way.”

“I had not observed the resemblance,” he said, rather coldly.

“Have some lemon-squash,” I said. The conversation seemed to be getting rather difficult.

“Thank you. Half a glassful, if I may.” The hell-brew appeared to buck him up, for he resumed in a slightly more pally manner. “I have a particular dislike for cats. But I was saying—— Oh, yes. Sometimes I am positively appalled at what I see around me. It is not only the cases which come under my professional notice, painful as many of those are. It is what I see as I go about London. Sometimes it seems to me that the whole world is mentally unbalanced. This very morning, for example, a most singular and distressing occurrence took place as I was driving from my house to the club. The day being clement, I had instructed my chauffeur to open my landaulette, and I was leaning back, deriving no little pleasure from the sunshine, when our progress was arrested in the middle of the thoroughfare by one of those blocks in the traffic which are inevitable in so congested a system as that of London.”

I suppose I had been letting my mind wander a bit, for when he stopped and took a sip of lemon-squash I had a feeling that I was listening to a lecture and was expected to say something.

“Hear, hear!” I said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Nothing, nothing. You were saying——”

“The vehicles proceeding in the opposite direction had also been temporarily arrested, but after a moment they were permitted to proceed. I had fallen into a meditation, when suddenly the most extraordinary thing took place. My hat was snatched abruptly from my head! And as I looked back I perceived it being waved in a kind of feverish triumph from the interior of a taxi-cab, which, even as I looked, disappeared through a gap in the traffic and was lost to sight.”

I didn’t laugh, but I distinctly heard a couple of my floating ribs part from their moorings under the strain.

“Must have been meant for a practical joke,” I said. “What?”

This suggestion didn’t seem to please the old boy.

“I trust,” he said, “I am not deficient in an appreciation of the humorous, but I confess that I am at a loss to detect anything akin to pleasantry in the outrage. The action was beyond all question that of a mentally unbalanced subject. These mental lesions may express themselves in almost any form. The Duke of Ramfurline, to whom I had occasion to allude just now, is under the impression—this is in the strictest confidence—that he is a canary; and his seizure to-day, which so perturbed Lord Alastair, was due to the fact that a careless footman had neglected to bring him his morning lump of sugar. Cases are common, again, of men waylaying women and cutting off portions of their hair. It is from a branch of this latter form of mania that I should be disposed to imagine that my assailant was suffering. I can only trust that he will be placed under proper control before he—— Mr. Wooster, there is a cat close at hand! It is not in the street! The mewing appears to come from the adjoining room.”

THIS time I had to admit there was no doubt about it. There was a distinct sound of mewing coming from the next room. I punched the bell for Jeeves, who drifted in and stood waiting with an air of respectful devotion.

“Sir?”

“Oh, Jeeves,” I said. “Cats! What about it? Are there any cats in the flat?”

“Only the three in your bedroom, sir.”

“What!”

“Cats in his bedroom!” I heard Sir Roderick whisper in a kind of stricken way, and his eyes hit me amidships like a couple of bullets.

“What do you mean,” I said, “only the three in my bedroom?”

“The black one, the tabby, and the small lemon-coloured animal, sir.”

“What on earth——?”

I charged round the table in the direction of the door. Unfortunately, Sir Roderick had just decided to edge in that direction himself, with the result that we collided in the doorway with a good deal of force, and staggered out into the hall together. He came smartly out of the clinch and grabbed an umbrella from the rack.

“Stand back!” he shouted, waving it over his head. “Stand back, sir! I am armed!”

It seemed to me that the moment had come to be soothing.

“Awfully sorry I barged into you,” I said. “Wouldn’t have had it happen for worlds. I was just dashing out to have a look into things.”

He appeared a trifle reassured, and lowered the umbrella. But just then the most frightful shindy started in the bedroom. It sounded as though all the cats in London, assisted by delegates from outlying suburbs, had got together to settle their differences once for all. A sort of augmented orchestra of cats.

“This noise is unendurable,” yelled Sir Roderick. “I cannot hear myself speak.”

“I fancy, sir,” said Jeeves, respectfully, “that the animals may have become somewhat exhilarated as the result of having discovered the fish under Mr. Wooster’s bed.”

The old boy tottered.

“Fish! Did I hear you rightly?”

“Sir?”

“Did you say that there was a fish under Mr. Wooster’s bed?”

“Yes, sir.”

Sir Roderick gave a low moan, and reached for his hat and stick.

“You aren’t going?” I said

“Mr. Wooster, I am going! I prefer to spend my leisure time in less eccentric society.”

“But I say. Here, I must come with you. I’m sure the whole business can be explained. Jeeves, my hat.”

Jeeves rallied round. I took the hat from him and shoved it on my head.

“Good heavens!”

Beastly shock it was! The bally thing had absolutely engulfed me, if you know what I mean. Even as I was putting it on I got a sort of impression that it was a trifle roomy; and no sooner had I let go of it than it settled down over my ears like a kind of extinguisher.

“I say! This isn’t my hat!”

“It is my hat!” said Sir Roderick in about the coldest, nastiest voice I’d ever heard. “The hat which was stolen from me this morning as I drove in my car.”

“But——”

I suppose Napoleon or somebody like that would have been equal to the situation, but I’m bound to say it was too much for me. I just stood there goggling in a sort of coma, while the old boy lifted the hat off me and turned to Jeeves.

“I should be glad, my man,” he said, “if you would accompany me a few yards down the street. I wish to ask you some questions.”

“Very good, sir.”

“Here, but, I say——!” I began, but he left me standing. He stalked out, followed by Jeeves. And at that moment the row in the bedroom started again, louder than ever.

I was about fed up with the whole thing. I mean, cats in your bedroom—a bit thick, what? I didn’t know how the dickens they had got in, but I was jolly well resolved that they weren’t going to stay picknicking there any longer. I flung open the door. I got a momentary flash of about a hundred and fifteen cats of all sizes and colours scrapping in the middle of the room, and then they all shot past me with a rush and out of the front door: and all that was left of the mob-scene was the head of a whacking big fish, lying on the carpet and staring up at me in a rather austere sort of way, as if it wanted a written explanation and apology.

There was something about the thing’s expression that absolutely chilled me, and I withdrew on tip-toe and shut the door. And. as I did so, I bumped into someone.

“Oh, sorry!” he said.

I spun round. It was the pink-faced chappie, Lord Something or other, the fellow I had met with Claude and Eustace.

“I say,” he said, apologetically, “awfully sorry to bother you, but those weren’t my cats I met just now legging it downstairs, were they? They looked like my cats.”

“They came out of my bedroom.”

“Then they were my cats!” he said, sadly. “Oh, dash it!”

“Did you put cats in my bedroom?”

“Your man, what’s his name, did. He rather decently said I could keep them there till my train went. I’d just come to fetch them. And now they’ve gone! Oh, well, it can’t be helped, I suppose. I’ll take the hat and the fish, anyway.”

I was beginning to dislike this chappie.

“Did you put that bally fish there, too?”

“No, that was Eustace’s. The hat was Claude’s.” I sank limply into a chair.

“I say, you couldn’t explain this, could you?” I said. The chappie gazed at me in mild surprise.

“Why, don’t you know all about it? I say!” He blushed profusely. “Why, if you don’t know about it, I shouldn’t wonder if the whole thing didn’t seem rummy to you.”

“Rummy is the word.”

“It was for The Seekers, you know.”

“The Seekers?”

“Rather a blood club, you know, up at Oxford, which your cousins and I are rather keen on getting into. You have to pinch something, you know, to get elected. Some sort of a souvenir, you know. A policeman’s helmet, you know, or a door-knocker or something, you know. The room’s decorated with the things at the annual dinner, and everybody makes speeches and all that sort of thing. Rather jolly! Well, we wanted rather to make a sort of special effort and do the thing in style, if you understand, so we came up to London to see if we couldn’t pick up something here that would be a bit out of the ordinary. And we had the most amazing luck right from the start. Your cousin Claude managed to collect a quite decent top-hat out of a passing car, and your cousin Eustace got away with a really goodish salmon or something from Harrods, and I snaffled three excellent cats all in the first hour. We were fearfully braced, I can tell you. And then the difficulty was to know where to park the things till our train went. You look so beastly conspicuous, you know, tooling about London with a fish and a lot of cats. And then Eustace remembered you, and we all came on here in a cab. You were out, but your man said it would be all right. When we met you, you were in such a hurry that we hadn’t time to explain. Well, I think I’ll be taking the hat, if you don’t mind.”

“It’s gone.”

“Gone?”

“The fellow you pinched it from happened to be the man who was lunching here. He took it away with him.”

“Oh, I say! Poor old Claude will be upset. Well, how about the goodish salmon or something?”

“Would you care to view the remains?” He seemed all broken up when he saw the wreckage.

“I doubt if the committee would accept that,” he said, sadly. “There isn’t a frightful lot of it left, what?”

“The cats ate the rest.”

He sighed deeply.

“No cats, no fish, no hat. We’ve had all our trouble for nothing. I do call that hard! And on top of that—I say, I hate to ask you, but you couldn’t lend me a tenner, could you?”

“A tenner? What for?”

“Well, the fact is, I’ve got to pop round and bail Claude and Eustace out. They’ve been arrested.”

“Arrested!”

“Yes. You see, what with the excitement of collaring the hat and the salmon or something, added to the fact that we had rather a festive lunch, they got a bit above themselves, poor chaps, and tried to pinch a motor-lorry. Silly, of course, because I don’t see how they could have got the thing to Oxford and showed it to the committee. Still, there wasn’t any reasoning with them, and, when the driver started making a fuss, there was a bit of a mix-up, and Claude and Eustace are more or less languishing in Vine Street police-station till I pop round and bail them out. So if you could manage a tenner—Oh, thanks, that’s fearfully good of you. It would have been too bad to leave them there, what? I mean, they’re both such frightfully good chaps, you know. Everybody likes them up at the ’Varsity. They’re fearfully popular.”

“I bet they are!” I said.

WHEN Jeeves came back, I was waiting for him on the mat. I wanted speech with the blighter.

“Well?” I said.

“Sir Roderick asked me a number of questions, sir, respecting your habits and mode of life, to which I replied guardedly.”

“I don’t care about that. What I want to know is why you didn’t explain the whole thing to him right at the start? A word from you would have put everything clear.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Now he’s gone off thinking me a looney.”

“I should not be surprised, from his conversation with me, sir, if some such idea had not entered his head.”

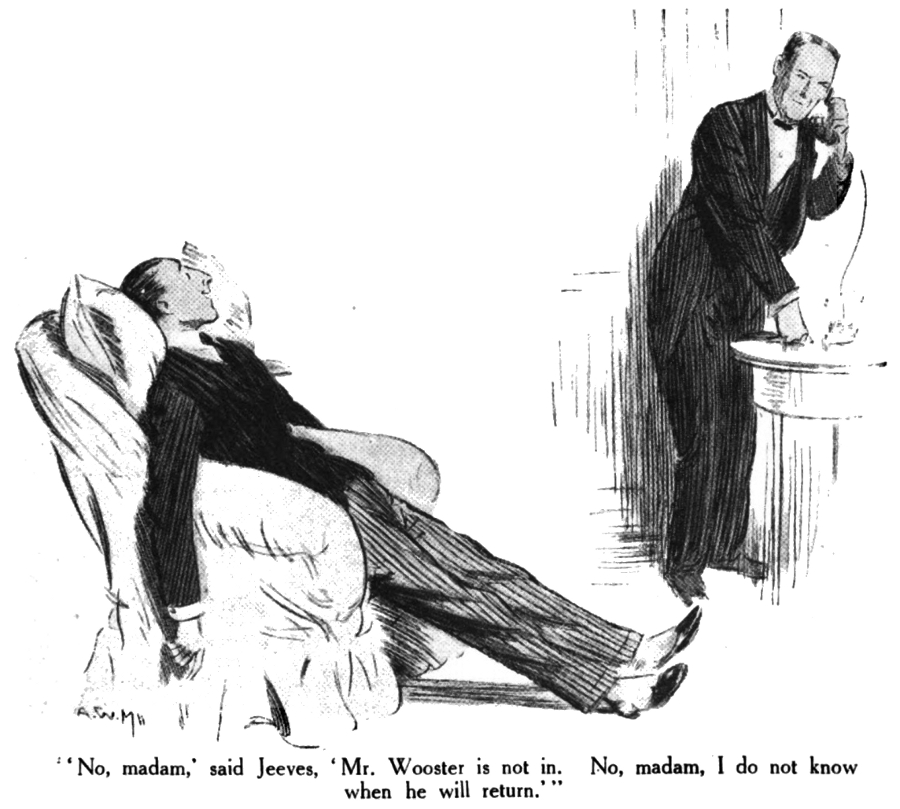

I was just starting in to speak, when the telephone-bell rang. Jeeves answered it.

“No, madam, Mr. Wooster is not in. No, madam, I do not know when he will return. No, madam, he left no message. Yes, madam, I will inform him.” He put back the receiver. “Mrs. Gregson, sir.”

Aunt Agatha! I had been expecting it. Ever since the luncheon-party had blown out a fuse, her shadow had been hanging over me, so to speak.

“Does she know? Already?”

“I gather that Sir Roderick has been speaking to her on the telephone, sir, and——”

“No wedding bells for me, what?”

Jeeves coughed.

“Mrs. Gregson did not actually confide in me, sir, but I fancy that some such thing may have occurred. She seemed decidedly agitated, sir.”

It’s a rummy thing, but I’d been so snootered by the old boy and the cats and the fish and the hat and the pink-faced chappie and all the rest of it that the bright side simply hadn’t occurred to me till now. By Jove, it was like a bally weight rolling off my chest! I gave a yelp of pure relief.

“Jeeves,” I said, “I believe you worked the whole thing!”

“Sir?”

“I believe you had the jolly old situation in hand right from the start.”

“Well, sir, Spenser, Mrs. Gregson’s butler, who inadvertently chanced to overhear something of your conversation when you were lunching at the house, did mention certain of the details to me; and I confess that, though it may be a liberty to say so, I entertained hopes that something might occur to prevent the match. I doubt if the young lady was entirely suitable to you, sir.”

“And she would have shot you out on your ear five minutes after the ceremony.”

“Yes, sir. Spenser informed me that she had expressed some such intention. Mrs. Gregson wishes you to call upon her immediately, sir.”

“She does, eh? What do you advise, Jeeves?”

“I think a trip to the south of France might prove enjoyable, sir.”

“Jeeves,” I said, “you are right, as always. Pack the old suit-case, and meet me at Victoria in time for the boat-train. I think that’s the manly, independent course, what?”

“Absolutely, sir!” said Jeeves.

(Next month: “Aunt Agatha Takes the Count.”)

For a very similar real-life case of aversion to cats mentioned by Wodehouse in other contexts, see the endnote about Lord Roberts at “The Man Who Disliked Cats.”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums