The Strand Magazine, January 1921

“I SAY, laddie!”

Archie spoke plaintively. Sheer amiability had led him to oblige his friend, James B. Wheeler, the well-known artist, by posing for the central figure in a cover which the latter was painting for one of the magazines; and already he was looking back ruefully to the time when he had supposed that an artist’s model had a soft job. In the first five minutes muscles which he had not been aware that he possessed had started to ache like neglected teeth. His respect for the toughness and durability of artists’ models was now solid. How they acquired the stamina to go through this sort of thing all day and then bound off to Bohemian revels at night was more than he could understand.

“Don’t wobble, confound you!” snorted Mr. Wheeler.

“Yes, but, my dear old artist,” said Archie, “what you don’t seem to grasp—what you appear not to realize—is that I’m getting a crick in the back.”

“You weakling! You miserable invertebrate worm! Move an inch, and I’ll murder you, and come and dance on your grave every Wednesday and Saturday. I’m just getting it.”

“It’s in the spine that it seems to catch me principally.”

“Be a man, you faint-hearted string-bean!” urged J. B. Wheeler. “You ought to be ashamed of yourself. Why, a girl who was posing for me last week stood for a solid hour on one leg, holding a tennis racket over her head and smiling brightly withal.”

“The female of the species is more india-rubbery than the male,” argued Archie.

“Well, I’ll be through in a few minutes. Don’t weaken. Think how proud you’ll be when you see yourself on all the bookstalls.”

Archie sighed, and braced himself to the task once more. He wished he had never taken on this binge. In addition to his physical discomfort, he was feeling a most awful chump. As it was mid-winter, the cover on which Mr. Wheeler was engaged was for the August number of the magazine, and it had been necessary for Archie to drape his reluctant form in a two-piece bathing suit of a vivid lemon colour; for he was supposed to be representing one of those jolly dogs belonging to the best families who dive off floats at exclusive seashore resorts. J. B. Wheeler, a stickler for accuracy, had wanted him to remove his socks and shoes; but there Archie had stood firm. He was willing to make an ass of himself, but not a silly ass.

“All right,” said J. B. Wheeler, laying down his brush. “That will do for to-day. Though, speaking without prejudice and with no wish to be offensive, if I had had a model who wasn’t a weak-kneed, jelly-backboned son of Belial, I could have got the darned thing finished without having to have another sitting.”

“I wonder why you chappies call this sort of thing ‘sitting,’ ” said Archie, pensively, as he conducted tentative experiments in osteopathy on his aching back. “I say, old thing, I could do with a restorative, if you have one handy. But of course you haven’t, I suppose,” he added, resignedly. Abstemious as a rule, there were moments when Archie found the Eighteenth Amendment somewhat trying.

J. B. Wheeler shook his head.

“You’re a little previous,” he said. “But come round in another day or so, and I may be able to do something for you.” He moved with a certain conspirator-like caution to a corner of the room, and, lifting to one side a pile of canvases, revealed a stout barrel, which he regarded with a fatherly and benignant eye. “I don’t mind telling you that, in the fullness of time, I believe this is going to spread a good deal of sweetness and light.”

“Oh, ah,” said Archie, interested. “Home-brew, what?”

“Made with these hands. I added a few more raisins yesterday, to speed things up a bit. There is much virtue in your raisin. And, talking of speeding things up, for goodness’ sake try to be a bit more punctual to-morrow. We lost an hour of good daylight to-day.”

“I like that! I was here on the absolute minute. I had to hang about on the landing waiting for you.”

“Well, well, that doesn’t matter,” said J. B. Wheeler, impatiently, for the artist soul is always annoyed by petty details. “The point is that we were an hour late in getting to work. Mind you’re here to-morrow at eleven sharp.”

IT was, therefore, with a feeling of guilt and trepidation that Archie mounted the stairs on the following morning; for in spite of his good resolutions he was half an hour behind time. He was relieved to find that his friend had also lagged by the wayside. The door of the studio was ajar, and he went in, to discover the place occupied by a lady of mature years, who was scrubbing the floor with a mop. He went into the bedroom and donned his bathing suit. When he emerged, ten minutes later, the charwoman had gone, but J. B. Wheeler was still absent. Rather glad of the respite, he sat down to kill time by reading the morning paper, whose sporting page alone he had managed to master at the breakfast table.

There was not a great deal in the paper to interest him. The usual bond-robbery had taken place on the previous day, and the police were reported hot on the trail of the Master-Mind who was alleged to be at the back of these financial operations. A messenger named Henry Babcock had been arrested and was expected to become confidential. To one who, like Archie, had never owned a bond, the story made little appeal. He turned with more interest to a cheery half-column on the activities of a gentleman in Minnesota who, with what seemed to Archie—who had been the victim of much persecution from his wife’s father—a good deal of resource and public spirit, had recently beaned his father-in-law with the family meat-axe. It was only after he had read this through twice in a spirit of gentle approval that it occurred to him that J. B. Wheeler was uncommonly late at the tryst. He looked at his watch, and found that he had been in the studio three-quarters of an hour.

Archie became restless. Long-suffering old bean though he was, he considered this a bit thick. He got up and went out on to the landing, to see if there were any signs of the blighter. There were none. He began to understand now what had happened. For some reason or other the bally artist was not coming to the studio at all that day. Probably he had called up the hotel and left a message to this effect, and Archie had just missed it. Another man might have waited to make certain that his message had reached its destination, but not woollen-headed Wheeler, the most casual individual in New York. Thoroughly aggrieved, Archie turned back to the studio to dress and go away.

His progress was stayed by a solid, forbidding slab of oak. Somehow or other, since he had left the room, the door had managed to get itself shut.

“Oh, dash it!” said Archie.

The mildness of the expletive was proof that the full horror of the situation had not immediately come home to him. His mind in the first few moments was occupied with the problem of how the door had got that way. He could not remember shutting it. Probably he had done it unconsciously. As a child, he had been taught by sedulous elders that the little gentleman always closed doors behind him, and presumably his subconscious self was still under the influence. And then, suddenly, he realized that this infernal, officious ass of a subconscious self had deposited him right in the gumbo. Behind that closed door, unattainable as youthful ambition, lay his gent’s heather-mixture with the green twill, and here he was, out in the world, alone, in a lemon-coloured bathing suit.

In all crises of human affairs there are two broad courses open to a man. He can stay where he is or he can go elsewhere. Archie, leaning on the banisters, examined these alternatives narrowly. If he stayed where he was he would have to spend the night on this dashed landing. If he legged it, in this kit, he would be gathered up by the constabulary before he had gone a hundred yards. He was no pessimist, but he was reluctantly forced to the conclusion that he was up against it.

It was while he was musing with a certain tenseness on these things that the sound of footsteps came to him from below. But almost in the first instant the hope that this might be J. B. Wheeler, the curse of the human race, died away. Whoever was coming up the stairs was running, and J. B. Wheeler never ran upstairs. He was not one of your lean, haggard, spiritual-looking geniuses. He made a large income with his brush and pencil, and spent most of it in creature comforts. This couldn’t be J. B. Wheeler.

It was not. It was a tall, thin man whom he had never seen before. He appeared to be in a considerable hurry. He let himself into the studio on the floor below, and vanished without even waiting to shut the door.

He had come and disappeared in almost record time, but, brief though his passing had been, it had been long enough to bring consolation to Archie. A sudden bright light had been vouchsafed to Archie, and he now saw an admirably ripe and fruity scheme for ending his troubles. What could be simpler than to toddle down one flight of stairs and in an easy and debonair manner ask the chappie’s permission to use his telephone? And what could be simpler, once he was at the ’phone, than to get in touch with somebody at the Cosmopolis who would send down a few trousers and what not in a kit-bag? It was a priceless solution, thought Archie, as he made his way downstairs. Not even embarrassing, he meant to say. This chappie, living in a place like this, wouldn’t bat an eyelid at the spectacle of a fellow trickling about the place in a bathing suit. They would have a good laugh about the whole thing.

“I say, I hate to bother you—dare say you’re busy and all that sort of thing—but would you mind if I popped in for half a second and used your ’phone?”

That was the speech, the extremely gentlemanly and well-phrased speech, which Archie had prepared to deliver the moment the man appeared. The reason he did not deliver it was that the man did not appear. He knocked, but nothing stirred.

“I say!”

Archie now perceived that the door was ajar, and that on an envelope attached with a tack to one of the panels was the name “Elmer M. Moon.” He pushed the door a little farther open and tried again.

“Oh, Mr. Moon! Mr. Moon!” He waited a moment. “Oh, Mr. Moon! Mr. Moon! Are you there, Mr. Moon?”

He blushed hotly. To his sensitive ear the words had sounded exactly like the opening line of the refrain of a Tin Pan Alley song-hit. He decided to waste no further speech on a man with such an unfortunate surname until he could see him face to face and get a chance of lowering his voice a bit. Absolutely absurd to stand outside a chappie’s door singing song-hits in a lemon-coloured bathing suit. He pushed the door open and walked in; and his subconscious self, always the gentleman, closed it gently behind him.

“Up!” said a low, sinister, harsh, unfriendly, and unpleasant voice.

“Eh?” said Archie, revolving sharply on his axis.

He found himself confronting the hurried gentleman who had run upstairs. This sprinter had produced an automatic pistol, and was pointing it in a truculent manner at his head. Archie stared at his host, and his host stared at him.

“Put your hands up,” he said.

“Oh, right-o! Absolutely!” said Archie. “But I mean to say——”

The other was drinking him in with considerable astonishment. Archie’s costume seemed to have made a powerful impression upon him.

“Who the devil are you?” he inquired.

“Me? Oh, my name’s——”

“Never mind your name. What are you doing here?”

“Well, as a matter of fact, I popped in to see if I might use your ’phone. You see——”

A certain relief seemed to temper the austerity of the other’s gaze. As a visitor, Archie, though surprising, seemed to be better than he had expected.

“I don’t know what to do with you,” he said, meditatively.

“If you’d just let me toddle to the ’phone——”

“Likely!” said the man. He appeared to reach a decision. “Here, go into that room.”

He indicated with a jerk of his head the open door of what was apparently a bedroom at the farther end.

“I take it,” said Archie, chattily, “that all this may seem to you not a little rummy.”

“Get on!”

“I was only saying——”

“Well, I haven’t time to listen. Get a move on!”

THE bedroom was in a state of untidiness which eclipsed anything which Archie had ever witnessed. The blighter appeared to be moving house. Bed, furniture, and floor were covered with articles of clothing. A silk shirt wreathed itself about Archie’s ankles as he stood gaping, and, as he moved farther into the room, his path was paved with ties and collars.

“Sit down!” said Elmer M. Moon, abruptly.

“Right-o! Thanks,” said Archie. “I suppose you wouldn’t like me to explain, and what not, what?”

“No!” said Mr. Moon. “I haven’t got your spare time. Put your hands behind that chair.”

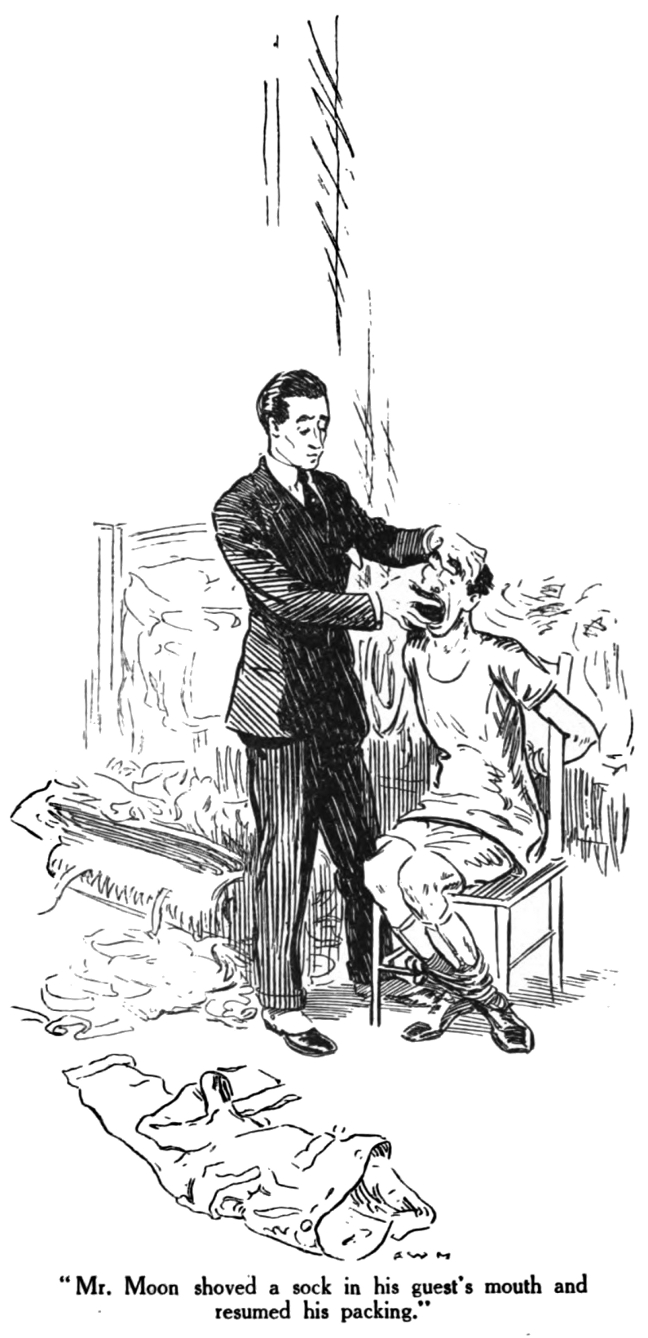

Archie did so, and found them immediately secured by what felt like a silk tie. His assiduous host then proceeded to fasten his ankles in a like manner. This done, he seemed to feel that he had done all that was required of him, and he returned to the packing of a large suit-case which stood by the window.

“I say!” said Archie.

Mr. Moon, with the air of a man who has remembered something

which he had overlooked, shoved a sock in his guest’s mouth and resumed

his packing. He was what might be called an impressionist packer. His aim

appeared to be speed rather than neatness. He bundled his belongings in,

closed the bag with some difficulty, and, stepping to the window, opened

it. Then he climbed out on to the fire-escape, dragged the suit-case after

him, and was gone.

Mr. Moon, with the air of a man who has remembered something

which he had overlooked, shoved a sock in his guest’s mouth and resumed

his packing. He was what might be called an impressionist packer. His aim

appeared to be speed rather than neatness. He bundled his belongings in,

closed the bag with some difficulty, and, stepping to the window, opened

it. Then he climbed out on to the fire-escape, dragged the suit-case after

him, and was gone.

Archie, left alone, addressed himself to the task of freeing his prisoned limbs. The job proved much easier than he had expected. Mr. Moon, that hustler, had wrought for the moment, not for all time. A practical man, he had been content to keep his visitor shackled merely for such a period as would permit him to make his escape unhindered. In less than ten minutes Archie, after a good deal of snake-like writhing, was pleased to discover that the thingummy attached to his wrists had loosened sufficiently to enable him to use his hands. He untied himself and got up.

He now began to tell himself that out of evil cometh good. His encounter with the elusive Mr. Moon had not been an agreeable one, but it had had this solid advantage, that it had left him right in the middle of a great many clothes. And Mr. Moon, whatever his moral defects, had the one excellent quality of taking about the same size as himself. Archie, casting a covetous eye upon a tweed suit which lay on the bed, was on the point of climbing into the trousers when on the outer door of the studio there sounded a forceful knocking.

“Open up here!”

Archie bounded silently out into the other room, and stood listening tensely. He was not a naturally querulous man, but he did feel at this point that fate was picking on him with a somewhat undue severity.

“In th’ name av th’ Law!”

There are times when the best of us lose our heads. At this juncture Archie should undoubtedly have gone to the door, opened it, explained his presence in a few well-chosen words, and generally have passed the whole thing off with ready tact. But the thought of confronting a posse of police in his present costume caused him to look earnestly about him for a hiding-place.

Up against the farther wall was a settee with a high, arching back, which might have been put there for that special purpose. He inserted himself behind this, just as a splintering crash announced that the Law, having gone through the formality of knocking with its knuckles, was now getting busy with an axe. A moment later the door had given way, and the room was full of trampling feet. Archie wedged himself against the wall with the quiet concentration of a clam nestling in its shell, and hoped for the best.

It seemed to him that his immediate future depended for better or for worse entirely on the native intelligence of the Force. If they were the bright, alert men he hoped they were, they would see all that junk in the bedroom and, deducing from it that their quarry had stood not upon the order of his going but had hopped it, would not waste time in searching a presumably empty apartment. If, on the other hand, they were the obtuse, flat-footed persons who occasionally find their way into the ranks of even the most enlightened constabularies, they would undoubtedly shift the settee and drag him into a publicity from which his modest soul shrank. He was enchanted, therefore, a few moments later, to hear a gruff voice state that th’ mutt had beaten it down th’ fire-escape. His opinion of the detective abilities of the New York police force rose with a bound.

There followed a brief council of war, which, as it took place in the bedroom, was inaudible to Archie except as a distant growling noise. He could distinguish no words, but, as it was succeeded by a general trampling of large boots in the direction of the door and then by silence, he gathered that the pack, having drawn the studio and found it empty, had decided to return to other and more profitable duties. He gave them a reasonable interval for removing themselves, and then poked his head cautiously over the settee.

All was peace. The place was empty. No sound disturbed the stillness.

Archie emerged. For the first time in this morning of disturbing occurrences he began to feel that God was in his heaven and all right with the world. At last things were beginning to brighten up a bit, and life might be said to have taken on some of the aspects of a good egg. He stretched himself, for it is cramping work lying under settees, and, proceeding to the bedroom, picked up the tweed trousers again.

Clothes had a fascination for Archie. Another man, in similar circumstances, might have hurried over his toilet; but Archie, faced by a difficult choice of ties, rather strung the thing out. He selected a specimen which did great credit to the taste of Mr. Moon, evidently one of our snappiest dressers, found that it did not harmonize with the deeper meaning of the tweed suit, removed it, chose another, and was adjusting the bow and admiring the effect, when his attention was diverted by a slight sound which was half a cough and half a sniff; and, turning, found himself gazing into the clear blue eyes of a large man in uniform, who had stepped into the room from the fire-escape. He was swinging a substantial club in a negligent sort of way, and he looked at Archie with a total absence of bonhomie.

“Ah!” he observed.

“Oh, there you are!” said Archie, subsiding weakly against the chest of drawers. He gulped. “Of course, I can see you’re thinking all this pretty tolerably weird and all that,” he proceeded, in a propitiatory voice.

The policeman attempted no analysis of his emotions. He opened a mouth which a moment before had looked incapable of being opened except with the assistance of powerful machinery, and shouted a single word:—

“Cassidy!”

A distant voice gave tongue in answer. It was like alligators roaring to their mates across lonely swamps. There was a rumble of footsteps in the region of the stairs, and presently there entered an even larger guardian of the Law than the first exhibit. He, too, swung a massive club, and, like his colleague, he gazed frostily at Archie.

“God save Ireland!” he remarked.

The words appeared to be more in the nature of an expletive than a practical comment on the situation. Having uttered them, he draped himself in the doorway like a colossus, and chewed gum.

“Where ja get him?” he inquired, after a pause.

“Found him in here attimpting to disguise himself.”

“I told Cap. he was hiding somewheres, but he would have it that he’d beat it down th’ escape,” said the gum-chewer, with the sombre triumph of the underling whose sound advice has been overruled by those above him. He shifted his wholesome (or, as some say, unwholesome) morsel to the other side of his mouth, and for the first time addressed Archie directly. “Ye’re pinched!” he observed.

ARCHIE started violently. The bleak directness of the speech roused him with a jerk from the dream-like state into which he had fallen. He had not anticipated this. He had assumed that there would be tedious explanations to be gone through before he was at liberty to depart to the cosy little lunch for which his interior had been sighing wistfully this long time past; but that he should be arrested had been outside his calculations. Of course, he could put everything right eventually; he could call witnesses to his character and the purity of his intentions; but in the meantime the whole dashed business would be in all the papers, embellished with all those unpleasant flippancies to which your newspaper reporter is so prone to stoop when he sees half a chance. He would feel a frightful chump. Chappies would rot him about it to the most fearful extent. Old Brewster’s name would come into it, and he could not disguise it from himself that his father-in-law, who liked his name in the papers as little as possible, would be sorer than a sunburned neck.

“No, I say, you know! I mean, I mean to say!”

“Pinched!” repeated the rather larger policeman.

“And annything ye say,” added his slightly smaller colleague, “will be used agenst ya ’t the trial.”

“And if ya try t’escape,” said the first speaker, twiddling his club, “ya’ll getja block knocked off.”

And, having sketched out this admirably clear and neatly-constructed scenario, the two relapsed into silence. Officer Cassidy restored his gum to circulation. Officer Donahue frowned sternly at his boots.

“But, I say,” said Archie, “it’s all a mistake, you know. Absolutely a frightful error, my dear old constables. I’m not the lad you’re after at all. The chappie you want is a different sort of fellow altogether. Another blighter entirely.”

New York policemen never laugh when on duty. There is probably something in the regulations against it. But Officer Donahue permitted the left corner of his mouth to twitch slightly, and a momentary muscular spasm disturbed the calm of Officer Cassidy’s granite features, as a passing breeze ruffles the surface of some bottomless lake.

“That’s what they all say!” observed Officer Donahue.

“It’s no use tryin’ that line of talk,” said Officer Cassidy. “Babcock’s squealed.”

“Sure. Squealed’s morning,” said Officer Donahue.

Archie’s memory stirred vaguely.

“Babcock?” he said. “Do you know, that name seems familiar to me somehow. I’m almost sure I’ve read it in the paper or something.”

“Ah, cut it out!” said Officer Cassidy, disgustedly. The two constables exchanged a glance of austere disapproval. This hypocrisy pained them. “Read it in th’ paper or something!”

“By Jove! I remember now. He’s the chappie who was arrested in that bond business. For goodness’ sake, my dear, merry old constables,” said Archie, astounded, “you surely aren’t labouring under the impression that I’m the Master-Mind they were talking about in the paper? Why, what an absolutely priceless notion! I mean to say, I ask you, what! Frankly, laddies, do I look like a Master-Mind?”

Officer Cassidy heaved a deep sigh, which rumbled up from his interior like the first muttering of a cyclone.

“If I’d known,” he said, regretfully, “that this guy was going to turn out a ruddy Englishman, I’d have taken a slap at him with m’ stick and chanced it!”

Officer Donahue considered the point well taken.

“Ah!” he said, understandingly. He regarded Archie with an unfriendly eye. “I know th’ sort well! Trampling on th’ face av th’ poor!”

“Ya c’n trample on the poor man’s face,” said Officer Cassidy, severely; “but don’t be surprised if one day he bites you in the leg!”

“But, my dear old sir,” protested Archie, “I’ve never trampled——”

“One of these days,” said Officer Donahue, moodily, “the Shannon will flow in blood to the sea!”

“Absolutely! But——”

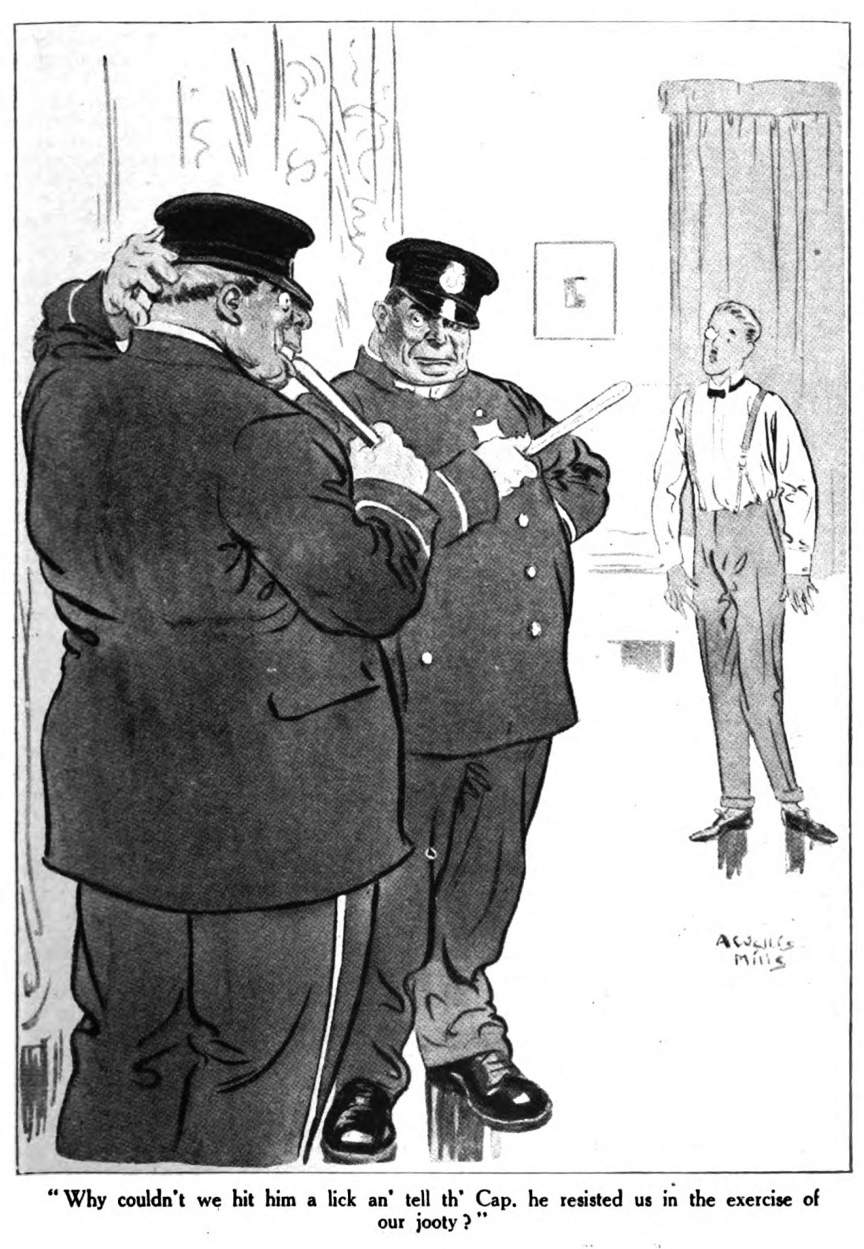

Officer Cassidy uttered a glad cry.

“Why couldn’t we hit him a lick,” he suggested, brightly, “an’ tell th’ Cap. he resisted us in th’ exercise of our jooty?”

An instant gleam of approval and enthusiasm came into Officer Donahue’s eyes. Officer Donahue was not a man who got these luminous inspirations himself, but that did not prevent him appreciating them in others and bestowing commendation in the right quarter. There was nothing petty or grudging about Officer Donahue.

“Ye’re the lad with the head, Tim!” he exclaimed, admiringly.

“It just sorta came to me,” said Mr. Cassidy, modestly.

“It’s a great idea, Timmy!”

“Just happened to think of it,” said Mr. Cassidy, with a coy gesture of self-effacement.

ARCHIE had listened to the dialogue with growing uneasiness. Not for the first time since he had made their acquaintance, he became vividly aware of the exceptional physical gifts of these two men. The New York police force demands from those who would join its ranks an extremely high standard of stature and sinew, but it was obvious that jolly old Donahue and Cassidy must have passed in first shot without any difficulty whatever.

“I say, you know,” he observed, apprehensively.

And then a sharp and commanding voice spoke from the outer room.

“Donahue! Cassidy! What the devil does this mean?”

Archie had a momentary impression that an angel had fluttered down to his rescue. If this was the case, the angel had assumed an effective disguise—that of a police captain. The new arrival was a far smaller man than his subordinates—so much smaller that it did Archie good to look at him. For a long time he had been wishing that it were possible to rest his eyes with the spectacle of something of a slightly less out-size nature than his two companions.

“Why have you left your posts?”

The effect of the interruption on the Messrs. Cassidy and Donahue was pleasingly instantaneous. They seemed to shrink to almost normal proportions, and their manner took on an attractive deference. Officer Donahue saluted.

“If ye plaze, sorr——”

Officer Cassidy also saluted, simultaneously.

“ ’Twas like this, sorr——”

The captain froze Officer Cassidy with a glance and, leaving him congealed, turned to Officer Donahue.

“Oi wuz standing on th’ fire-escape, sorr,” said Officer Donahue, in a tone of obsequious respect which not only delighted but astounded Archie, who hadn’t known he could talk like that, “accordin’ to instructions, when I heard a suspicious noise. I crope in, sorr, and found this duck—found the accused, sorr—in front of th’ mirror, examinin’ himself. I then called to Officer Cassidy for assistance. We pinched—arrested um, sorr.”

The captain looked at Archie. It seemed to Archie that he looked at him coldly and with contempt.

“Who is he?”

“The Master-Mind, sorr.”

“The what?”

“The accused, sorr. The man that’s wanted.”

“You may want him. I don’t,” said the captain. Archie, though relieved, thought he might have put it more nicely. “This isn’t Moon. It’s not a bit like him.”

“Absolutely not!” agreed Archie, cordially. “It’s all a mistake, old companion, as I was trying to——”

“Cut it out!”

“Oh, right-o!”

“You’ve seen the photographs at the station. Do you mean to tell me you see any resemblance?”

“If ye plaze, sorr,” said Officer Cassidy, coming to life.

“Well?”

“We thought he’d bin disguising himself, the way he wouldn’t be recognized.”

“You’re a fool!” said the captain.

“Yes, sorr,” said Officer Cassidy, meekly.

“So are you, Donahue.”

“Yes, sorr.”

Archie’s respect for this chappie was going up all the time. He seemed to be able to take years off the lives of these massive blighters with a word. It was like the stories you read about lion-tamers. Archie did not despair of seeing Officer Donahue and his old college chum Cassidy eventually jumping through hoops.

“Who are you?” demanded the captain, turning to Archie.

“Well, my name is——”

“What are you doing here?”

“Well, it’s rather a longish story, you know. Don’t want to bore you, and all that.”

“I’m here to listen. You can’t bore me.”

“Dashed nice of you to put it like that,” said Archie, gratefully. “I mean to say, makes it easier and so forth. What I mean is, you know how rotten you feel telling the deuce of a long yarn and wondering if the party of the second part is wishing you would turn off the tap and go home. I mean——”

“If,” said the captain, “you’re reciting something, stop. If you’re trying to tell me what you’re doing here, make it shorter and easier.”

Archie saw his point. Of course, time was money—the modern spirit of hustle—all that sort of thing.

“Well, it was this bathing suit, you know,” he said.

“What bathing suit?”

“Mine, don’t you know. A lemon-coloured contrivance. Rather bright and so forth, but in its proper place not altogether a bad egg. Well, the whole thing started, you know, with my standing on a bally pedestal sort of arrangement in a diving attitude—for the cover, you know. I don’t know if you have ever done anything of that kind yourself, but it gives you a most fearful crick in the spine. However, that’s rather beside the point, I suppose—don’t know why I mentioned it. Well, this morning he was dashed late, so I went out——”

“What the devil are you talking about?”

Archie looked at him, surprised.

“Aren’t I making it clear?”

“No.”

“Well, you understand about the bathing suit, don’t you? The jolly old bathing suit, you’ve grasped that, what?”

“No.”

“Oh, I say,” said Archie. “That’s rather a nuisance. I mean to say, the bathing suit’s what you might call the good old pivot of the whole dashed affair, you see. Well, you understand about the cover, what? You’re pretty clear on the subject of the cover?”

“What cover?”

“Why, for the magazine.”

“What magazine?”

“Now there you rather have me. One of these bright little periodicals, you know, that you see popping to and fro on the bookstalls.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said the captain. He looked at Archie with an expression of distrust and hostility. “And I’ll tell you straight out I don’t like the looks of you. I believe you’re a pal of his.”

“No longer,” said Archie, firmly. “I mean to say, a chappie who makes you stand on a bally pedestal sort of arrangement and get a crick in the spine, and then doesn’t turn up and leaves you biffing all over the countryside in a bathing suit——”

THE reintroduction of the bathing suit motive seemed to have the worst effect on the captain. He flushed darkly.

“Are you trying to josh me? I’ve a mind to soak you!”

“If ye plaze, sorr,” cried Officer Donahue and Officer Cassidy in chorus. In the course of their professional career they did not often hear their superior make many suggestions with which they saw eye to eye, but he had certainly, in their opinion, spoken a mouthful now.

“No, honestly, my dear old thing, nothing was farther from my thoughts——”

He would have spoken further, but at this moment the world came to an end. At least, that was how it sounded. Somewhere in the immediate neighbourhood something went off with a vast explosion, shattering the glass in the window, peeling the plaster from the ceiling, and sending him staggering into the inhospitable arms of Officer Donahue.

The three guardians of the Law stared at one another.

The three guardians of the Law stared at one another.

“If ye plaze, sorr,” said Officer Cassidy, saluting.

“Well?”

“May I spake, sorr?”

“Well?”

“Something’s exploded, sorr!”

The information, kindly meant though it was, seemed to annoy the captain.

“What the devil did you think I thought had happened?” he demanded, with not a little irritation. “It was a bomb!”

Archie could have corrected this diagnosis, for already a faint but appealing aroma of an alcoholic nature was creeping into the room through a hole in the ceiling, and there had risen before his eyes the picture of J. B. Wheeler affectionately regarding that barrel of his on the previous morning in the studio upstairs. J. B. Wheeler had wanted quick results, and he had got them. Archie had long since ceased to regard J. B. Wheeler as anything but a tumour on the social system, but he was bound to admit that he had certainly done him a good turn now. Already these honest men, diverted by the superior attraction of this latest happening, appeared to have forgotten his existence.

“Sorr!” said Officer Donahue.

“Well?”

“It came from upstairs, sorr.”

“Of course it came from upstairs. Cassidy!”

“Sorr?”

“Get down into the street, call up the reserves, and stand at the front entrance to keep the crowd back. We’ll have the whole city here in five minutes.”

“Right, sorr.”

“Don’t let anyone in.”

“No, sorr.”

“Well, see that you don’t. Come along, Donahue, now. Look slippy.”

“On the spot, sorr!” said Donahue.

A moment later Archie had the room to himself. Two minutes later he was picking his way cautiously down the fire-escape after the manner of the recent Mr. Moon. Archie had not seen much of Mr. Moon, but he had seen enough to know that in certain crises his methods were sound and should be followed. Elmer Moon was not a good man; his ethics were poor and his moral code shaky; but in the matter of legging it away from a situation of peril and discomfort he had no superior.

(The concluding story in this series will appear next month.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums