The Strand Magazine, February 1927

I.

“COMEDY,” says Hazlitt, “is a graceful ornament to the civil order; the Corinthian capital of polished society. . . . It reflects the images of grace, of gaiety, and pleasure, and completes the perspective of human life.” Hazlitt might have written these words to-day, with a P. G. Wodehouse story at his elbow.

The most popular living English humorist, the creator of Psmith, Jeeves, Archie, and Ukridge, has very distinct views on his own craft. If an historian were to divide humorous writers into two main classes, the Satirists and the Humanists, P. G. Wodehouse would take his stand firmly with the human group. For pure satire he has no manner of use: he doesn’t look at things that way. Always the satirist is out for blood; he is determined to “tear off the mask of imposture from the world.” But P. G. Wodehouse is out for laughter only. He sees the foibles of human nature, the stupidity and cupidity, the pose and jealousies and footling pride, the freakishness of cults, the follies of the bigot and the boor—he sees it all, and smiles, and quietly quotes an old adage about stones and glass houses. Cruelty and injustice apart, the weaknesses of humankind sting him neither to wrath nor scorn; there is always a chuckle hovering round the corner, and he is after it with a butterfly net.

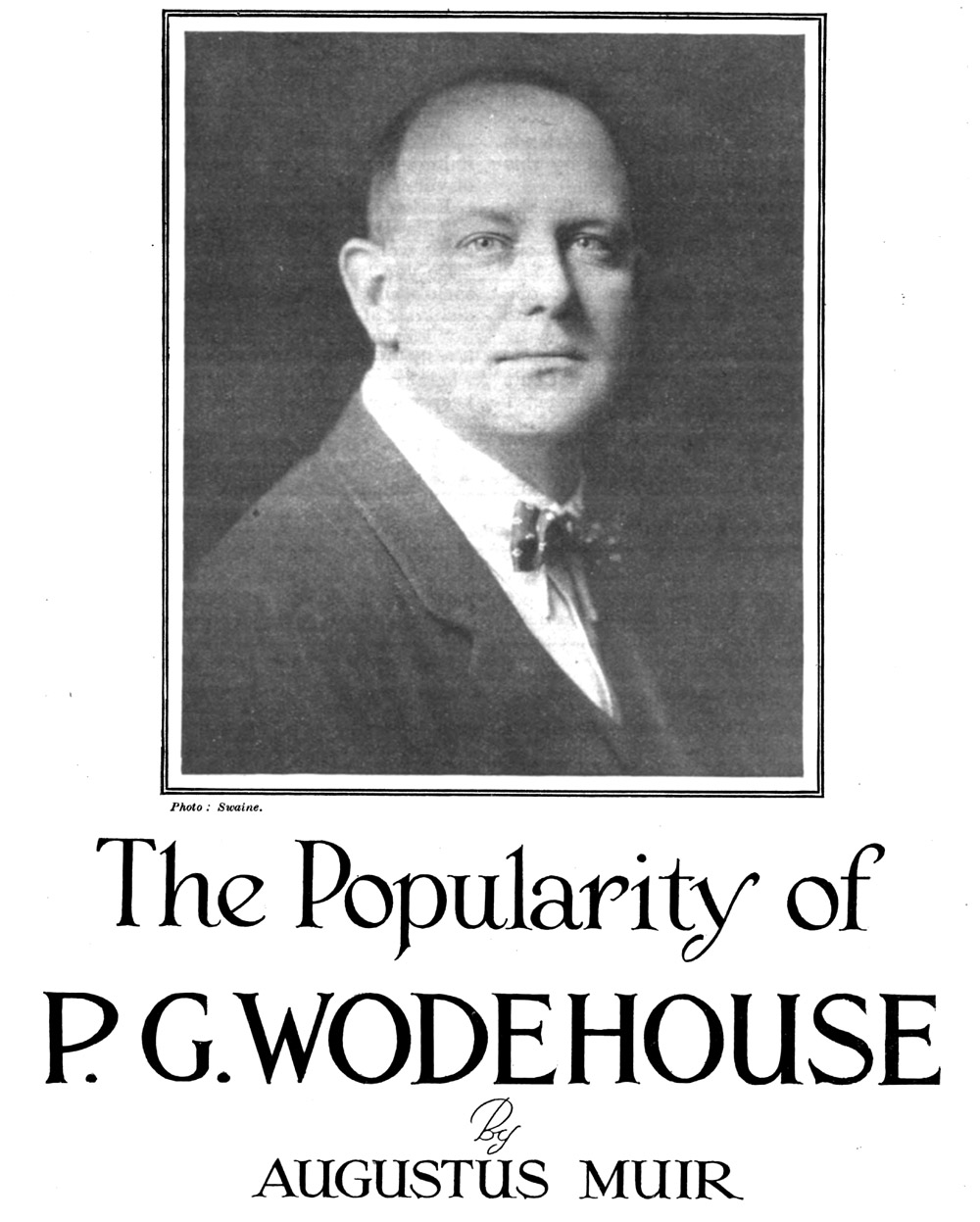

You could tell at a glance that he’s that sort of fellow. Often a humorist is pictured as a long, lean, miserable man, with a cadaverous face, a bad liver, and a Phil May fringe: a man with a permanent grouch, whose humour is but an anodyne against the pains of a joyless world. To that figure P. G. Wodehouse is as violent a contrast as you could imagine. A big, broad, ruddy, clear-eyed fellow; an open-air man, no hater of wind or rain; in his day a boxer, swimmer, cricketer, Rugby-player; a kindly, easy, matey, shy sort of chap, like a senior public-school boy who refuses to grow older. Quite unsophisticated, as though the Success, with a mighty big S, which has come to him was one of the least important things in his world. A man with an eager gusto for friendship. His eyes betray him. “Some theorist has held the view,” said R. L. Stevenson, “that there is no feature in man so tell-tale as his spectacles; that the mouth may be compressed and the brow smoothed artificially, but the sheen of the barnacles is diagnostic.” P. G.’s spectacles have a radiating sheen of tolerant good-nature.

GOOD-NATURE: that is the keynote of the man and his work. Even his own career he refuses to regard seriously, affirming that nothing of the slightest importance has ever happened to him. The truth is that from the beginning his career has been a romance, the progressive sub-titles of which might be: Hard Work and Hope; Hard Work but Up Against It; Hard Work and Success.

Educated at Dulwich, he entered the Hong-Kong and Shanghai Bank. There he carefully refrained from scribbling jests and light verse on his blotting-pad, as the bank did not regard itself as a self-endowed forcing-house for youthful genius; but in his spare time he scribbled hard. Two years passed; then in 1902 came a juncture which deserves to be called Crisis One. He was offered a job with the bank out East.

For a young fellow with a taste for new experiences the temptation was obvious. We have to thank Sir William Beach-Thomas for his counter-offer of work on the famous “By the Way” column of The Globe. E. V. Lucas, C. L. Graves, Harold Begbie, Stephen Phillips had all sharpened their prentice wits on the same column; A. S. M. Hutchinson worked on it for a few days, shortly before his appointment on the staff of The Evening Standard. P. G. Wodehouse took the job. It was tough work, writing a column a day, six days a week. There was no time to nibble your pen; in something under two hours the thews and sinews had to be torn out of the morning papers, a witty comment tacked on to each, a set of light verses composed, and all put to press by eleven-thirty a.m., in time for the early edition. Invaluable experience it proved for P. G. Wodehouse. At this daily task he acquired the facility that now enables him to turn out, if need be, the best part of a musical comedy during an Atlantic voyage. For seven years he worked on this daily column, and his manner of leaving it brings us abruptly to the second crisis in his career. P. G. Wodehouse turned his eyes westward.

The chance that now came to him arose out of the occupation of his leisure hours. Probably no journalist before or since has striven harder as a free-lance, battering at editorial doors with futile wads of contributions. Articles of the Tit-Bits order streamed from his pen; during one month, when a plebeian dose of mumps chained him to his room, he wrote thirty stories. He sold not one. But a little later he had success in Punch; and the pages of The Public School Magazine were opened to him by the acceptance of an article on school sport for which he received the gracious honorarium of half a guinea. “The Babe and the Dragon,” a short story included later in his book, “Tales of St. Austin’s,” gained him admittance to The Captain. Among the enthusiastic readers of that magazine—a magazine whose memory will be for ever beloved by thousands of Old Boys the world over—P. G. Wodehouse made a great reputation. Perhaps it is the reputation he most values to-day. Those boys who read “The Gold Bat,” “The Head of Kay’s,” “The White Feather,” and the Mike Jackson and Psmith serials in the pages of the old Captain will remain readers of P. G. Wodehouse as long as they live. They form the nucleus of his British public to-day; they are his staunchest adherents.

But the singular thing, on looking back, is that in the years when he wrote these stories he seemed to be incapable of writing anything else. He felt at home with boys; though in his middle twenties, he was still a boy at heart; but when he attempted a yarn about grown-ups, the wheels of his invention became clogged, and editors grimly shook their heads. To-day Wodehouse is staggered at the dramatic emergence of a group of writers who, at twenty-five and under, seem to have plumbed the depths of all experience, and to whom the human soul is an open and mostly a melancholy book. At these beardless Tolstoys, these stripling Tchekovs, on whom the dolour of youth seems to have settled like a blanket of damp fog, Wodehouse gasps with amazement.

His own twenties were years of hard, happy, and financially unsuccessful toil. “Love Among the Chickens” belongs to this period, but it did not bring him a fortune. In 1909, however, the finger of Fate is discernible. P. G. got five weeks’ holiday, and decided to spend it in the United States. It was a country to which he had always felt drawn. His holiday visit there brought him to the parting of the waters; with a bundle of stories as his frail canoe and a pen as his paddle, he made the great decision.

II.

IT all came about in the simple way things often have. Within a week or two of landing in New York, Wodehouse sold two stories to American magazines. The price he got amazed him. In these days sixty pounds for a story was like the discovery of some new El Dorado, like the Caliph of Bagdad at his door with jewels and gold. But the problem was how long he would remain on nodding terms with the Caliph. P. G. decided to risk it. He sent his resignation to The Globe and settled down in New York to turn out the best stories that were in him. Soon critics talked of him there as the new O. Henry. On the appearance of his fiction in The Strand Magazine the beginnings of real solid success came in England. In The Strand, of course, thousands of Captain boys, now grown older, read him eagerly. But at last a wide public felt that into their sky a new star had swung, with a light all its own; they recognized a new accent in English humour, a new lightness of touch, a new gaiety of spirit. For seventeen years the work of P. G. Wodehouse has been published regularly in The Strand, and for many years his short stories have appeared in no other British magazine.

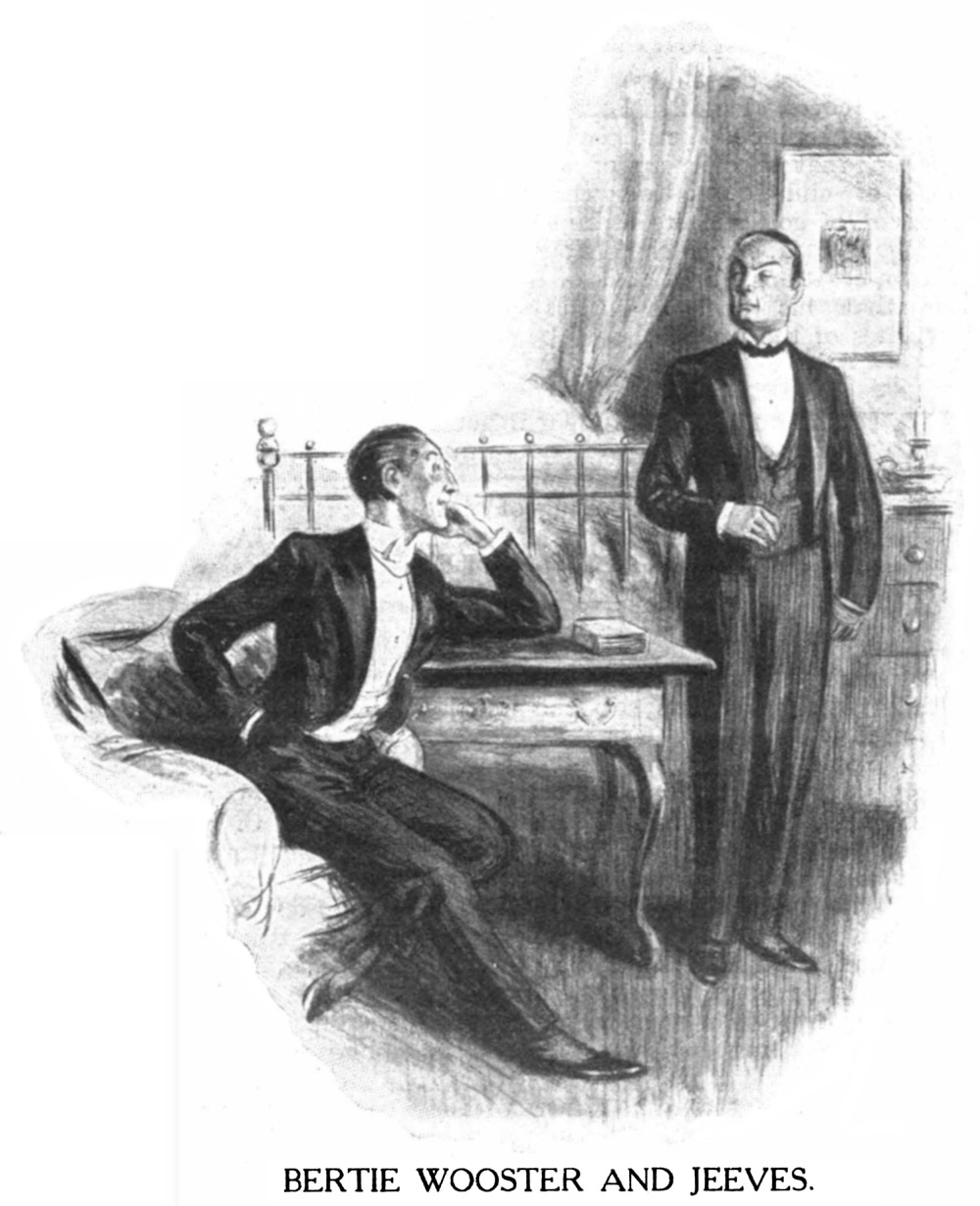

But I am anticipating. Since 1909, seventeen years have passed. Wodehouse was twenty-eight then, and now he is forty-five. These years between have been filled with incessant work. The position he has won as the most popular English humorist has only been achieved by sheer hard grind; no literary success, other than the flash-in-the-pan variety, was ever won by anything else. He has had his ups and downs, and the graph of his early fortunes, if carefully plotted, would pursue the zigzag coarse of a fever-chart. Just as Lord Birkenhead wrote in seven nights a legal text-book to raise the wherewithal to marry on,  in similar happy-go-lucky circumstances P. G. Wodehouse married a charming English girl in New York, determined to make the guineas and the dollars roll in as they had never rolled before. In the teeth of so vigorous an onslaught, difficulties slowly began to melt. And one of the principal protagonists in this slowly culminating tale of success was a certain young gentleman with a taste for fancy socks and neckties; he carried a gold-knobbed cane; the terms “old fruit” and “old bean” sprang often to his lips; he had the kindest heart in the world, and the thickest head. His name was Bertie Wooster.

in similar happy-go-lucky circumstances P. G. Wodehouse married a charming English girl in New York, determined to make the guineas and the dollars roll in as they had never rolled before. In the teeth of so vigorous an onslaught, difficulties slowly began to melt. And one of the principal protagonists in this slowly culminating tale of success was a certain young gentleman with a taste for fancy socks and neckties; he carried a gold-knobbed cane; the terms “old fruit” and “old bean” sprang often to his lips; he had the kindest heart in the world, and the thickest head. His name was Bertie Wooster.

III.

AMERICA ate Bertie Wooster. So did England for that matter, and one must not forget Scotland and the English-speaking islands of the seven seas. “What ho!” as a greeting has simply dropped clean out of the common parlance of our gilded youth. Bertie Wooster killed it stone-dead. For how could a fellow talk to a fellow like a fellow in a book? It isn’t done. That shows the strangle-hold that Bertie has on a certain section of Mayfair. Like a butterfly, the English “chappie” has been impaled for ever on a pin, and held up for popular inspection, by the creator of Bertie Wooster and Archie and their jovial coterie of kindred chumps.

With the quickening of popular demand, P. G. Wodehouse devoted a series, and then another, to the delineation of sublime foppery. But Bertie is more than a fool: he is a human fool, which makes all the difference. Bertie, who never lived, is more true to life than Beau Brummell, who did. Brummell was a coxcomb with a wit but no soul: Bertie has so much soul that quagmires simply yawn before him. There is a streak of Bertie in the most stolid of us. We do not laugh at him; we laugh at ourselves in Bertie’s predicaments. That is where P. G.’s skill comes in. Granted that the light which plays on his stage is a light that never was on land or sea, yet in his yarns there is truth to the spirit of things. For our laughter springs from pity and not scorn; and we read P. G. Wodehouse to see the little real or imagined hitches of our own lives reflected in the distorting mirror which he holds up with a gesture of such gay, grotesque hilarity.

With the quickening of popular demand, P. G. Wodehouse devoted a series, and then another, to the delineation of sublime foppery. But Bertie is more than a fool: he is a human fool, which makes all the difference. Bertie, who never lived, is more true to life than Beau Brummell, who did. Brummell was a coxcomb with a wit but no soul: Bertie has so much soul that quagmires simply yawn before him. There is a streak of Bertie in the most stolid of us. We do not laugh at him; we laugh at ourselves in Bertie’s predicaments. That is where P. G.’s skill comes in. Granted that the light which plays on his stage is a light that never was on land or sea, yet in his yarns there is truth to the spirit of things. For our laughter springs from pity and not scorn; and we read P. G. Wodehouse to see the little real or imagined hitches of our own lives reflected in the distorting mirror which he holds up with a gesture of such gay, grotesque hilarity.

It was one of those hitches in the unquiet existence of Bertie Wooster that caused the creation of Jeeves: that strong and silent valet, that super-wise counsellor. Bertie, who was always doing somebody a bit of good, had got himself into such a mess that Wodehouse boggled at the solution. Could Bertie extricate himself from that hole? Never: it wasn’t in him. Nor had any of his roistering pals sufficient grey matter to assist. Slowly turning the problem over, there arose in Wodehouse’s brain a wan and nebulous wraith, a sort of Slave of the Lamp, whose lineaments gradually hardened, till in his inner ear the author heard a soft cough, and a mellow voice said: “You rang, sir?” It was Jeeves: it was the perfect man-servant: it was the very fellow he wanted. From that day onward Jeeves took charge of Bertie’s affairs. And note again the author’s skill. Jeeves is the person everybody is looking for—not necessarily as a valet, but as one who hands out counsel that is wiser than the counsel of Solomon. What a relief it would be, in moments of doubt, if the tobacconist round the corner, for example, were a man just like Jeeves! Shouldn’t we take his advice—shouldn’t we refrain from rocketing off, like Bertie, and mulling up the fine points of the Jeeves suggestion—shouldn’t we . . . But there; we shall never know Jeeves. He is immaculate. He is a dream that cannot come true. We would relinquish a lot in life before we let go this Wodehouse vision of the valet who is almost the family solicitor.

Psycho-analysts, of course, will explain that P. G.’s conception has sprung from the fact that he suffers from a butler complex. It is true certainly that he both loves and fears that stern race of men. As a small boy he had difficulty in stifling the impulse to dig some butler in the ribs and see what would happen; he has been smothering the impulse ever since. The advice of Freud or Jung is perfectly plain in this case. To cure himself the patient must have one good dig—and blow the consequences. But let us hope that that dig will never take place; it might shatter the bright image of Jeeves in a thousand fragments. Like ticket-collectors and Prime Ministers, beneath the crust butlers are human: Jeeves is ideal.

Psmith—staid, lank, and supercilious—has, of course, grown up a little since school-days, when he was a lost lamb at Sedleigh with Mike Jackson, the last of a line of doughty cricketers. Psmith was not drawn direct from real life, but Wodehouse confesses that the character did have a counterpart. A friend at Winchester told him of a long, thin, haughty youth who wore an eyeglass, and in reply to his housemaster’s greeting, “How are you, ——?” would adjust his eyeglass and make such reply as “Sir, I grow thinnah and thinnah!” Such a character had intriguing possibilities, and in the end P. G. put it into a story.

Psmith—staid, lank, and supercilious—has, of course, grown up a little since school-days, when he was a lost lamb at Sedleigh with Mike Jackson, the last of a line of doughty cricketers. Psmith was not drawn direct from real life, but Wodehouse confesses that the character did have a counterpart. A friend at Winchester told him of a long, thin, haughty youth who wore an eyeglass, and in reply to his housemaster’s greeting, “How are you, ——?” would adjust his eyeglass and make such reply as “Sir, I grow thinnah and thinnah!” Such a character had intriguing possibilities, and in the end P. G. put it into a story.

In his hands Psmith has grown into something approaching a national comic figure. If the average plain, blunt Englishman met Psmith for the first time in real life, he would want to kick him, and kick him hard; but soon he would learn his mistake, and would find that a warm heart glows beneath the flawless uncreased waistcoat, that his wits are at the service of his weaker brethren, and that Psmith’s brand of “psocialism” is a sane attitude of mind rather than a virulent political creed. To America, Psmith typifies the imperturbable Englishman, just as Bertie is the human friendly Silly Ass to the nth, and Archie the sublimation of all the young bucks who have ever waked the echoes at the coffee-stall in Piccadilly about the time the first milk-cart rattles past.

Ukridge, that modern Micawber, is international; there must surely be Ukridges among even the Hottentots. In many guises, and under many names, he has been the theme of poets of all ages. He is Merlin chasing the Gleam of Fortune; he is knightly chivalry and gay improvidence, melted down and poured into a rather shabby suit of ready-mades. His poor cracked shield bears the device of a Hopeful Heart, and the local pop-shop has just refused to advance him two bob on it. As a fact, a fellow exactly like Ukridge did have an existence in reality. He was an acquaintance of W. Townend, one of P. G.’s oldest friends, and himself a writer we do not see enough of. Townend’s descriptions of the quaint bird were diverting. Situations began to build themselves around him. Pounded by the Wodehouse pestle, heated in the Wodehouse crucible, Ukridge emerged as the man we all know, complete to the bit of ginger-beer wire holding together his spectacles.

Ukridge, that modern Micawber, is international; there must surely be Ukridges among even the Hottentots. In many guises, and under many names, he has been the theme of poets of all ages. He is Merlin chasing the Gleam of Fortune; he is knightly chivalry and gay improvidence, melted down and poured into a rather shabby suit of ready-mades. His poor cracked shield bears the device of a Hopeful Heart, and the local pop-shop has just refused to advance him two bob on it. As a fact, a fellow exactly like Ukridge did have an existence in reality. He was an acquaintance of W. Townend, one of P. G.’s oldest friends, and himself a writer we do not see enough of. Townend’s descriptions of the quaint bird were diverting. Situations began to build themselves around him. Pounded by the Wodehouse pestle, heated in the Wodehouse crucible, Ukridge emerged as the man we all know, complete to the bit of ginger-beer wire holding together his spectacles.

His first appearance was in “Love Among the Chickens,” but he has developed amazingly since those days. Together with Bertie, Jeeves, Psmith, Lord Emsworth, that absent-minded peer, and the Oldest Member, that snapper-up of unconsidered trifles of club-house lore, that supreme exponent of golf and its lurking tragedies, Ukridge is P. G.’s favourite character among his own creations. And it is of interest to note that his own favourites are the favourites of the public also.

IV.

“WHERE on earth does the man get his ideas from?” It is a frequent question. For P. G. Wodehouse, the building of character, the devising of atmosphere, are almost unconscious processes; they are the easy, the pleasant, part of the business. It is the plot, the hook on which the whole thing hangs, that demands the toughest of brain-work. Wodehouse has drawers packed with newspaper cuttings; he never lets slip the simplest news note which might form the germ of a yarn. Sometimes the anecdote of a pal will give him an idea. Unlike most authors, he keeps no note-book; he detests the things; but in his desk he has bundles of typewritten foolscap sheets covered with seed-thoughts for future work. The idea fixed, he sits down solidly in an arm-chair, pipe in mouth, and hammers the plot out of the raw stuff that pleasant day-dreams are made on.

The first draft of a yarn he rushes off at high speed on his typewriter. Some authors, like Arnold Bennett, put down a sentence, and that sentence goes to the printer without the alteration of a word. Wodehouse reads and polishes, re-reads and re-types, balancing one part with another, cutting ruthlessly till sometimes a story is lopped down to half its initial length. To re-write three or four times is nothing to him; often he takes fifteen trial shots at the beginning of a yarn before he is confident that he has got his readers in a ju-jitsu grip within the first few paragraphs. The truth is that P. G. Wodehouse has an acute instinctive sense of form. His technique—neglecting, of course, his mannerisms, which are another matter—would form a fruitful subject for any young writer to study. “The proportion of one part to another and to the whole,” said R. L. Stevenson; “the elision of the useless, the accentuation of the important, and the preservation of a uniform character from end to end—these, taken together, constitute technical perfection.” And whether the matter in hand be a gay farce or a sombre folk-tale, a lyric or a scientific study of sand-dunes, technique is technique.

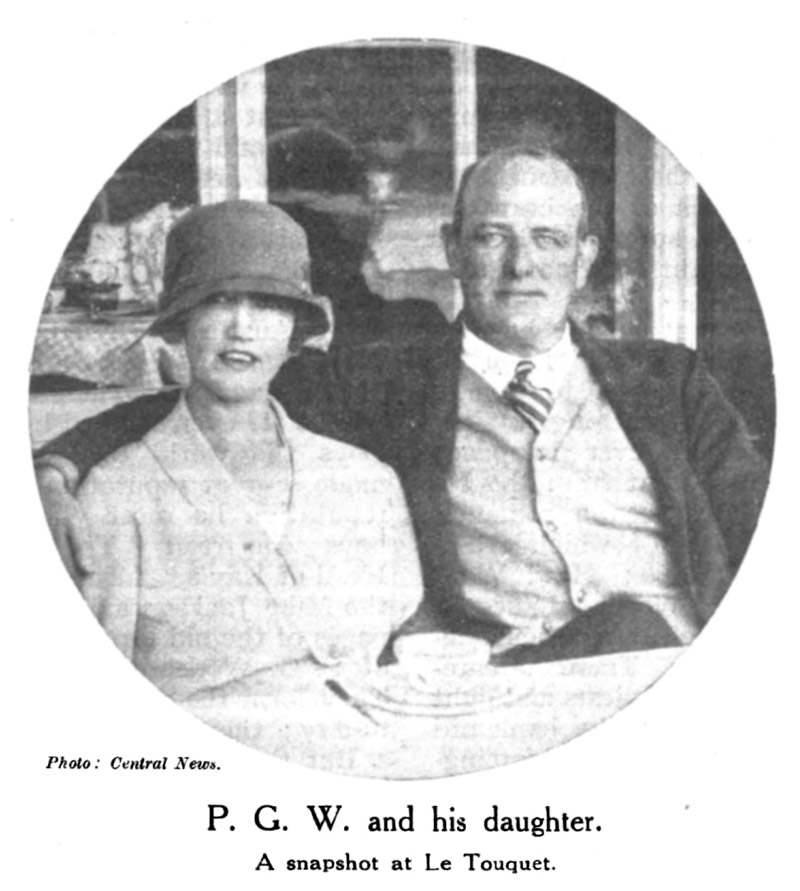

P. G. Wodehouse is never quite satisfied that he has written a story as well as that story can be written. He likes to lay aside a piece of work, and come back to it in a week or a month, with his critical faculties undulled by the warmth of recent composition. His wife and daughter also sit in judgment, thus completing a mixed triumvirate of censors who weigh every phrase and assess the potency of each chuckle, before the manuscript is passed out for publication. The result of all this labour is not only popular acclamation, but the warm approval of our literary critics, who appreciate his clean-cut prose and the skilled chiselling of his narrative style. Our best-selling humorist is also, like Leonard Merrick, a writer’s writer.

P. G. Wodehouse is never quite satisfied that he has written a story as well as that story can be written. He likes to lay aside a piece of work, and come back to it in a week or a month, with his critical faculties undulled by the warmth of recent composition. His wife and daughter also sit in judgment, thus completing a mixed triumvirate of censors who weigh every phrase and assess the potency of each chuckle, before the manuscript is passed out for publication. The result of all this labour is not only popular acclamation, but the warm approval of our literary critics, who appreciate his clean-cut prose and the skilled chiselling of his narrative style. Our best-selling humorist is also, like Leonard Merrick, a writer’s writer.

PERHAPS the most essential part of his day’s work is a five-mile tramp. In cloth cap and heavy brogues he sets out, rain or fine, from his house near Park Lane; and for a real good country walk he considers there is nothing to beat the streets of London. His work is grouped round this morning or afternoon tramp, and is largely dependent on it. Which is what we should expect from a writer who has never produced a yarn that did not have a high breeze blowing through it. More than that, he is one of the few authors who devote ten minutes every morning to a rigid system of physical exercises. Against such rigours, those moods of gloom, which are the proverbial portion of the professional humorist, stand no earthly chance. To be fit is to be happy, might be taken as one of his main rules of life. Always in fighting trim, he never needs a holiday; at Hunstanton or Monte Carlo, at Le Touquet or Long Island, he spends several hours each day at his typewriter.

With much travel he has acquired the knack of writing under all manner of conditions. He is not the type of fidgety genius who must have the picture of a mauve sunset above his desk, or a green golliwog strapped to his inkpot, for inspiration. He is as much at home drifting in a punt with his typewriter, as sitting at the dressing-table of an hotel bedroom, or in the swaying cabin of an Atlantic liner. Give him a kitchen table in an attic, and he is happy. His one crotchet is the old typewriter which he bought second-hand fifteen years ago in New York. It goes with him everywhere, this ancient and serviceable machine. He trembles with fear as he watches railway porters stagger with it across a platform. He has bought other machines, only to discard them for the old, tried friend. For the Wodehouse museum of the future, his typewriter, with its huge, unwieldy case, will be the principal exhibit!

V.

YOU can tell a man by his hobbies as well as by his friends. A love for sport of all kinds has been second nature with P. G. Wodehouse. At Dulwich he was in both the cricket and football teams; and to-day he is nearly as keen on watching these games as ever he was to play them. If he is in England, he faithfully reports every important Dulwich Rugby match for his old school magazine; some of the best work he ever did has been turned out for its columns. Proficient in both swimming and boxing, “The White Feather,” which he published about twenty years ago in The Captain and issued later in book form, is a boxing classic. He considers it among the best of his own school stories; it certainly shows an inside knowledge of the sport, and contains one of the best descriptions of the psychology of a ring-fight in modern literature.

His present game is golf, but you won’t catch him talking about it. He prefers to leave the talking to the other man. It is the human side of golf that interests him.

A niblick on the golf-bag’s rim,

A simple niblick is to him,

And it is nothing more.

But if golf is not altogether an obsession—except as material for his side-splitting golf stories—talk to him about dogs and his eye will brighten. Dogs take to P. G. instinctively: they spot him at once as a potential pal. And now that he has bought a house and shaken himself down permanently in London, he will, if he is not careful, be setting up in rivalry to the famous Battersea institution, and be collecting dogs as other men collect stamps.

If in his somewhat nomadic life, lived partly in England, partly in America, he found it impossible to cart dogs across the Atlantic, he could cart as many books as the tonnage would allow. His library is inclusive, rather than selective, and his tastes catholic. By dint of watchful perseverance, he is able to read the novels of Edgar Wallace almost as fast as they tumble from the dictaphone of that modern Eugene Sue. Unlike many humorists, Wodehouse gets enormous pleasure from the works of other humorous writers. Ian Hay, Denis Mackail, D. B. Wyndham Lewis, Harry Leon Wilson, and Ben Travers (particularly “Mischief”) are among his favourites, and his appreciation of them is as frank and sincere as if he himself had never coined a jest. James Branch Cabell and George Meredith jostle near at hand on his bookshelves; Babbitt he considers a creation of genius; and Bob Pretty, that rustic rapscallion of W. W. Jacobs, has given him many an honest chuckle.

Wodehouse has written enormously for the American musical comedy stage, and on this side had a hand in the production of “Kissing Time,” “The Cabaret Girl,” “The Golden Moth,” and others. But, like Barrie, he is no great theatre-goer, though he is a great clubman. He has been co-opted as a member of so many clubs that he is apt to lose count; but you will not find him in those places where epigrams are hurled across the tankards. He prefers to take refuge in a quiet corner of the Constitutional, that vast caravanserai in Northumberland Avenue, where in the depths of an arm-chair he feels as peaceful and safe from interruption as a traveller on an oasis of the Sahara desert.

America might be classed as one of his principal hobbies. He went there on a visit as far back as 1904, five years previous to the critical voyage when he decided to dig in his roots on the other side. Since then the sky-line of New York has altered as radically as the fashions and the food. “Even nowadays, if I stay away for more than six months,” he says, “I go back to find the whole place is different. They’re sure to have pulled down some sky-scrapers in the interval, and rushed up taller ones in their places.” And they probably call them heaven-bumpers or something quite new, for in these present days they change their slang more speedily than their Presidents. “New York is a great city,” says P. G.; “a fine city—if it weren’t for the motor-cars—thousands upon thousands of them, tearing everywhere, battling their way through the crush. Why don’t they prohibit motor-cars instead of the other thing?”

VI.

AT present P. G. Wodehouse is preparing to tackle a new novel; the theme is simmering. One of these mornings he will pull on a white sweater and sit down to the job of composition. It will be a humorous book, though in the case of most humorists that does not go without saying. Dan Leno longed to play Hamlet; Mark Twain shrank from the public conception of himself as a mere merry-maker. But P. G. is racked with no desire to stray outside his own orbit. His ambition is to write his own type of story as well as it can be written. To do one’s own work as well as it can be done: come to think of it, could ambition aim higher? At the point of a pistol, P. G. Wodehouse might admit that he hopes to leave this world a more cheerful place than he found it. Such, in these none-too-cheerful post-war days, is his mission.

I have to add a word about the man’s modesty. “Plum,” as his friends call him, is one of the most unspoilt fellows I have ever met, and will talk about everything in the world except himself. When he does touch on his own affairs, it is with the shy air of a Rugby player who has done well for his side rather than as the author who has scored a tremendous personal success by his own endeavours.

The stories of Wodehouse form the bedside books of statesmen and professors, as well as the plain, ordinary, unknown Englishman. Lord Oxford and Asquith acknowledges himself a frank devotee; from the contemplation of philosophic doubt, Lord Balfour turns with relief to the creator of Jeeves; in the opinion of so sound a critic as Robert Lynd, the best holiday reading in the world is “anything by Dr. Johnson and something by P. G. Wodehouse”; while Sir Oliver Lodge believes both in spirits and high spirits—“ ‘Jill the Reckless’ I consider a masterpiece,” he says; “the entire book is as good and wholesome a piece of humour as has been produced in this generation. . . . I am not sure that we of this generation are sufficiently appreciative of the good work that is being produced now.”

Laudatus a laudatis, and with an enormous public in England and America crying out for more and more of his work, P. G. Wodehouse has at last reaped the reward of his early efforts. His stories supply a need; they satisfy a hunger. And when the details of them fade from our mind, the spirit of them remains, a jolly possession. The writer’s broad and healthy humanity, his gay outlook, his happy-go-lucky gesture to life: these remain. “The true comic spirit is in the blossom of the nettle, not the sting.” P. G. Wodehouse culls the blossoms of good-humour, leaving the stings of bitterness for lesser men to pick.

A new P. G. Wodehouse Story next month.

Editor’s notes:

“Comedy,” says Hazlitt: From Lecture IV:

“On Wycherley, Congreve, Vanbrugh, and Farquhar” in “Lectures on the Comic Writers, etc. of Great Britain” in The Collected Works of William Hazlitt, vol. 8.

“tear off the mask of imposture”: Also from Hazlitt, from Lecture VI: “On Swift, Young, Gray, Collins, etc.” in “Lectures on the English Poets” in The Collected Works of William Hazlitt, vol. 5.

Phil May fringe: English caricaturist Phil May (1864–1903) wore his front hair in a fringe combed down his forehead.

Stevenson…spectacles: In Memories and Portraits (1887).

“By the Way” column: For more, see The P. G. Wodehouse Globe Reclamation Project on this site.

the new O. Henry: See Cosmopolitan magazine’s editorial announcement of his stories.

the light that never was on land or sea: See the notes to “Christmas Presents”.

butler complex: For more, see “All About Butlers”.

Stevenson…proportion of one part to another: In “A Note on Realism” in Later Essays.

niblick on the golf-bag’s rim, a simple niblick is to him: A take-off on Wordsworth’s “primrose by a river’s brim” from “Peter Bell” (1819).

Constitutional Club: Norman Murphy (In Search of Blandings, 1986) makes a good case for identifying this club as the prototype of the Senior Conservative, which appears in many books from Psmith in the City onwards.

blossom of the nettle: From Coleridge, “Lecture IX” of A Course of Lectures (1818).

Other Wodehouse books and stories referenced in this article may be found in the menu of titles on this website.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums