The Strand Magazine, May 1914

T

was a delightful sunny morning in mid-July, and Dermot

Windleband, sitting with his wife at breakfast on the veranda which overlooked

the rolling lawns and leafy woods of his charming Sussex home, was enjoying it

to the full. His Napoleonic features (his features were like that because he

was a Napoleon of Finance) were relaxed in a placid half-smile of lazy

contentment; and his wife (who liked to act sometimes as his secretary) found

it difficult to get him to pay any attention to his morning mail.

T

was a delightful sunny morning in mid-July, and Dermot

Windleband, sitting with his wife at breakfast on the veranda which overlooked

the rolling lawns and leafy woods of his charming Sussex home, was enjoying it

to the full. His Napoleonic features (his features were like that because he

was a Napoleon of Finance) were relaxed in a placid half-smile of lazy

contentment; and his wife (who liked to act sometimes as his secretary) found

it difficult to get him to pay any attention to his morning mail.

Mrs. Windleband liked to act sometimes as her husband’s secretary, because it recalled old times. In point of fact she had once been his secretary. Dermot had married her, with the least possible delay, on discovering that she had provided herself with a duplicate key to his safe and was in the habit, during his absence, of going very thoroughly through his private papers.

Almost all financiers of anything like real eminence marry their secretaries. It is, on the whole, cheaper to keep a wife who knows all one’s secrets than to pay the salary which a secretary who happened to know them would demand.

“There’s an article here, in the Financial Argus, of which you really must take notice,” Mrs. Windleband gently insisted. “It’s most abusive. It’s about the Wildcat Reef. They assert that there never was any gold in the mine and that you knew that perfectly well when you floated the company.” She put down the paper for a moment and looked inquiringly at her husband. “That’s not true, is it? You had the usual mining expert’s report, didn’t you?”

“Of course we had. Very satisfactory report, too. Unfortunately the fellow who wrote it depended rather on the ineradicable optimism of his nature than on any examination of the mine. As a matter of fact he never went near it.”

Mrs. Windleband whistled.

“That’s rather awkward. The Argus say that they have sent out an expert of their own to make inquiries, and hope to have his report for publication within the next fortnight. What are you going to do about it?”

“Nothing,” replied Dermot, with a yawn. “And, to save you the trouble of wading any farther through that mass of dreary correspondence, I may inform you that, for the future, I propose to do nothing about everything.”

“Dermot!”

Her husband went on placidly:—

“Not to put too fine a point on it, dear Heart-of-Gold, the gaff is blown—the game is up. The Napoleon of Finance is about to meet his Waterloo.”

“Surely things are not as bad as all that?”

“They’re worse. I’m absolutely up against it this time.”

The failure to lay his hands upon so pitiful a sum as twenty thousand pounds was, he proceeded to explain to his wondering wife, to be the cause of his undoing. Twenty thousand pounds had to be found within the next fortnight, or—they would have to book their passages to the dear old Argentine.

“But twenty thousand pounds!” objected Mrs. Windleband, incredulously; “you must be able to get that. Why, it’s a mere fleabite.”

“On paper—in the form of shares, script, bonds, promissory notes—twenty thousand pounds is, I grant you, a fleabite. But when the sum has to be produced in the raw—in flat, hard lumps of gold, then it begins to assume the proportions of a bite from a hippopotamus. I can’t raise it, dear Moon-of-my-Desire, and that’s all about it. So there we are; or, to put it more accurately, here we shall very shortly not be. The Old Guard, Josephine, have failed to rally round their beloved Emperor; so—St. Helena for Napoleon.”

Although Dermot Windleband described himself as a Napoleon of Finance, a Cinquevalli of Finance would, perhaps, have been the more accurate description. As a juggler with other people’s money Dermot was emphatically the Great and Only. And yet his method—like the methods of all Great and Onlies—was, when one came to examine it, simple in the extreme. Say, for instance, that the Home-Grown Tobacco Trust—founded by Dermot in a moment of ennui—failed, for some inexplicable reason, to yield those profits which the glowing prospectus had led all and sundry to expect; Dermot would appease the angry shareholders by giving them preference shares (interest guaranteed) in the Sea-Gold Extraction Company, hastily floated to meet the emergency. When the interest became due it would, as likely as not, be paid out of the capital just subscribed for the King Solomon’s Mines Exploitation Company, the little deficiency in the latter being replaced in its turn, when absolutely necessary and not before—by the transfer of some portion of the capital just raised for yet another company. And so on, ad infinitum. It was more like the Mad Hatter’s tea-party than anything else.

The only flaw in Dermot’s otherwise excellent method was that he could never stop and take a rest. He had to keep on all the time floating new companies to keep the existing ones afloat. Sometimes, in his more optimistic moments, he cherished a wild hope that he would succeed one day in floating a company that would, by some fluke, pay its way, and so give him a chance to catch up with himself; but the day, somehow, never seemed to arrive. He had solved the problem of Perpetual Promotion, and had to suffer the consequences of his own ingenuity.

On the whole, it was rather a relief than otherwise to Dermot to discover that the game was up. He had had about enough of it. Still, he objected to the manner of his defeat. Twenty thousand pounds ought not to have caused the fall of one who had in his time handled millions—even if most of those millions were only on paper. Twenty thousand pounds was not enough. The amount was not Napoleonic. It ought to have been two hundred thousand pounds at the very least. The ignominious character of the defeat that stared him in the face was the one factor that inclined Dermot to go on with the fight, if by any possibility it could be managed.

“Are you absolutely sure, Dermot, that nothing can be done?” persisted Mrs. Windleband, doggedly. “Have you tried everyone?”

“Everyone—the Possibles, the Probables, the Might-be-Touched, and even the Highly-Unlikelies. Never an echo came to the minstrel’s wooing song. No, my dear; we’ve got to take to the boats this time, and that right soon. Unless, of course, someone possessed at one and the same time of twenty thousand pounds and a very confiding nature, happens to tumble out of the sky.”

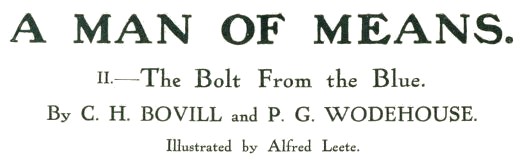

As the words left his lips an aeroplane came sailing over the tops of the trees that lay below them. Gracefully as any bird it came down on the lawn—not twenty yards from where the Windlebands were seated.

“Who is the intrepid aviator?” queried Dermot, lazily, as a nimble little figure, clad in overalls, hopped from the machine and helped out his companion, whose clumsy progress to earth was rather that of the landsman getting out of an open boat in which he has spent a long and perilous night at sea. “Looks like one of those French chaps.”

“Doesn’t matter a bit who the intrepid aviator is,” rejoined Mrs. Windleband, in a voice that shook with unwonted excitement. “It’s the other man that I’m interested in. Don’t you see who it is? That’s Roland Bleke.”

“Roland Bleke?” The Napoleon of Finance shook his head. The name seemed to convey nothing to him.

“Yes, yes—Roland Bleke!” repeated Mrs. Windleband, impatiently. “My dear, you must have heard of him. The man who won the Calcutta Sweep and was kidnapped, or something, at Lexingham yesterday by that French aviator—what’s his name?—Etienne Feriaud. The papers are full of it this morning.”

“Ah, I haven’t read the papers this morning. Hence my ignorance on the score of Mr. Roland Bleke. The world knows nothing of its greatest men. How on earth did you recognize the chap?”

“From his picture, of course.”

She pointed to a photograph which adorned the front page of one of the illustrated dailies that lay on the table before them. Dermot glanced at it, and then said, admiringly, to his wife:—

“What a wonderful woman you are! I couldn’t have done that. You must get the gift from your uncle.”

Mrs. Windleband’s uncle was one of those learned professors who can recognize a giant mastodon from a shin-bone dug out of an African swamp.

“I think,” said Mrs. Windleband, “that we ought to go and see what we can do for Mr. Bleke.”

“I don’t,” rejoined her husband, decidedly. “They’ve torn up our croquet lawn with that infernal machine of theirs. My instincts are all against stirring a finger on Mr. Bleke’s behalf.”

His wife stared at him in astonishment.

“Are you quite well, dear?” she asked, in an anxious tone. “You don’t seem to understand. Roland Bleke netted forty thousand pounds when he won the Calcutta Sweep. That was only a little more than a month ago. From what they say of him in the papers—it seems he’s only a seed merchant’s clerk in some small provincial town—he can’t have spent it all yet. He wouldn’t know how.”

A light began to dawn upon her husband. He rose quickly from his chair. The old fighting spirit asserted itself once more. Napoleon was himself again. Waterloo might yet be averted.

“ ‘You made me love you—I didn’t want to do it,’ ” he hummed, inconsequently. “But, by gum, if ever a man married the right woman it was my father’s only son. Come along, old girl. You’re quite right. The commonest instincts of humanity demand that we should go to the assistance of this unfortunate Mr. Bleke.”

When they got down to where the aeroplane was lying they found the little man in overalls busy tinkering at the engine. His companion was watching the operation in a helpless sort of way, and the Windlebands noticed that, in spite of the heat of the morning, he was shivering violently.

“Not had an accident, I hope, Mr. Bleke?” inquired Dermot, pleasantly.

Roland Bleke turned and looked at him with watery, lack-lustre eyes. Roland was being kept too busy, by one of the worst colds of the century, to have time to wonder, even, how this stranger came to know his name.

“Doe; doe accident, thag you,” he replied, miserably, as he blew his nose. “Somethig’s gone wrog; but it’s not very serious, I’m afraig.”

M. Feriaud, having by this time adjusted the defect in his engine, rose to his feet and bowed to the Windlebands.

“Excuse if we come down on your lawn,” he said, apologetically, “but we do not trespass long. See, mon ami,” he turned, radiant, to Roland, “everything O.K. now. We go on.”

“No,” said Roland, very decidedly.

“Hein? What you mean—No?”

“I mean that I’m not going on.”

A shade of alarm clouded M. Feriaud’s weather-beaten features. The eminent bird-man did not wish to part with Roland. Towards Roland he felt like a brother. Roland had notions about payment for little aeroplane flights which bordered on princely.

“But you cannot give up now,” he objected, almost tearfully. “You say, ‘Take me to France wis you——’ ”

“Daresay I did,” admitted Roland. “But it’s all off now; see? Rather than trust myself again in that machine of yours I’d——”

What it was that he would rather do than trust himself again to the aeroplane Roland Bleke, for some reason, elected not to divulge; but his manner gave one to understand that it would be something considerable.

“But it is not fair! It is all wrong!” protested M. Feriaud, turning with an aggrieved air of appeal to the Windlebands, and gesticulating freely in illustration of his wrongs. “He give me one hundred pounds to take him away from Lexingham. Good, it is here.” He slapped his breast pocket. “But the other two hundred pounds which he promise to pay me when I land him safe across the Shannel—where is zat?” He took Roland by the arm. “No, no, mon ami; business are business. You must come wis me.”

Roland broke away from the birdman’s clutch.

“I will give you,” he said, hastily getting out his pocket-book, “two hundred and fifty pounds to leave me safe where I am.”

A smile of brotherly forgiveness lit up M. Feriaud’s face. The generous Gallic nature asserted itself. He held out his arms affectionately to Roland.

“Ah—now you talk!” he cried, in his impetuous way. “Embrassez-moi, mon cher! You are fine shap.”

Roland escaped the proffered embrace by busying himself with counting out the bank-notes which he had taken from his case.

Roland heaved a sigh of relief when, five minutes later, the aeroplane rose dizzily into the air and flew away in the direction of the sea; then he indulged in a series of sneezes that made the welkin ring.

“You’re not well, you know,” said Dermot, looking at him critically.

“I’ve caught a slide cold, I fadcy,” said Roland, accompanying the remark with a trumpet obbligato on his handkerchief. “You see, we’ve been flying about more or less all night—that French ass lost his bearings—and my suit is a bit thin. But I’m all right.”

“You’re not all right, my dear boy,” insisted Mrs. Windleband, with an air of almost motherly solicitude. “You ought to be in bed.”

“Perhaps you’re right,” admitted Roland, looking helplessly round, as though he expected to see a bed somewhere on the surrounding lawn. “Can you tell me if there is an hotel anywhere near?”

“Hotel? I’m not going to let a man in your condition go to any hotel,” announced Dermot, in his big-hearted way, taking Roland, as he spoke, firmly by the arm. “You’re coming right into my house and up to bed this instant minute.”

Roland’s first instinct, when he discovered that the Good Samaritan who had taken him in was no less a personage than the great Dermot Windleband, was to struggle out of bed and make his escape, even though the effort were to cost him his life. Dermot Windleband was a name which Roland, during his mercantile career, had learned to hold in something closely approaching to reverence—as that of one of the mightiest business brains of our time. Even old Fineberg, whose opinion of humanity at large was unflattering in the extreme, accorded to Dermot Windleband a sort of grudging admiration.

To have to meet so eminent a person in the capacity of an invalid—a nuisance about the house—made Roland long for a rapidly fatal termination to his illness. The kindnesses of the Windlebands—and there seemed to be nothing that they were not ready to do for him—worried him almost into his grave. When Mrs. Windleband came into the room in which he lay and, with her own hands, poured out his medicine and put his bed straight, and then sat down and read to him, Roland suffered tortures of embarrassment. Mrs. Windleband was an angel, he admitted that; but angels’ visits, to a man of retiring disposition, are apt to be trying. He felt even worse when the great Dermot himself came up to the sick-room and sprawled genially over the bed, chatting away just as if he were an ordinary human being and not one of the Master-Minds of the Century. Roland wanted to hide his head under the bed-clothes, so unworthy did he feel of this high honour.

How he came to tell the Windlebands all about the unfortunate matter of Muriel Coppin, Roland never quite knew; but he did. They were very sympathetic. Mrs. Windleband said she could see clearly that Muriel was a designing young woman, from whom Roland was quite right to run away. The great Dermot was of the same opinion, but added that he feared his spirited action was going to cost Roland a bit.

“Tell you what I’ll do,” said Dermot, after thinking over the situation for a while, “I’ll send my own lawyer down to her with, say, one thousand pounds—not a cheque, understand, but one thousand golden sovereigns that he can show her—roll about on the table in front of her eyes. Very few people of that class can resist money when they see it in the raw. She’ll probably jump at the thousand and you’ll be out of your trouble.”

“I’d rather make it two thousand,” said Roland. He had never loved Muriel Coppin, and the idea of marrying her had been a sort of nightmare to him, but he wanted to retreat with honour.

“Very well, make it two, if you like,” assented Dermot, indifferently; “though I don’t quite know how old Harrison is going to carry all that money.”

As a matter of fact, old Harrison never had to try. On thinking it over (after he had cashed Roland’s cheque) Dermot came to the conclusion that seven hundred pounds would be quite as much money as it would be good for Miss Coppin to have all at once; and so it was with seven hundred sovereigns only that old Harrison was sent out on his errand of temptation. As Dermot had foreseen, the sight of the virgin gold was too much for Miss Coppin. She jumped at it.

Roland, man-like, was a little disappointed when he heard that Muriel had agreed to settle. Glad as he was to escape marrying her, he did feel that she ought to have demanded higher compensation than a beggarly two thousand pounds for his loss. He hinted this to Dermot. In the circumstances Dermot did the right—the tactful thing. He forebore from hurting his guest’s feelings still further by enlightening him to the fact that Miss Coppin had been quite content to accept a market valuation of her lost lover which amounted to little more than a third of that sum.

Roland was able to sit up and take nourishment—nay, to come down to the dining-room and take nourishment in large quantities—before the Napoleon of Finance began the real campaign.

Dermot selected with care the right strategic moment at which to strike the first blow. It was after dinner—and a remarkably good dinner at that—a dinner at which the wines had been of the choicest and the liqueurs perfection. Roland’s experience of dinners at which the wines were of the choicest and the liqueurs perfection was strictly limited. Moreover, during the period of convalescence from influenza few men are at the height of their alertness. Consequently, the conditions were highly favourable—from the Napoleonic point of view.

“You know, Bleke, I’ve taken a great fancy to you,” said Dermot, suddenly, as they sat smoking together, after Mrs. Windleband had left the room.

Roland blushed with gratification. His private estimate of himself was, he felt, at last being justified. The Coppins hadn’t thought much of him; Muriel had patently preferred a mere mechanic; old Fineberg had treated him more or less as dirt; but, by Jove, Dermot Windleband, one of the master-brains of our time, could see the stuff in him.

“It’s very kind of you to say so, Mr. Windleband,” he murmured, diffidently.

“Bosh! Shouldn’t say it if I didn’t mean it,” was the brusque rejoinder. “I have taken a fancy to you—so much so, that I’m going to do for you what I very seldom do for any man.”

Roland said something futile about too much having been done for him already. Dermot waved the suggestion aside.

“Nonsense—only too glad. Now look here, Bleke; as a general rule I don’t give tips——”

“You’re quite right,” agreed Roland, warmly. “I think the tipping system is iniquitous. It ought to be abolished.”

“Ah—I don’t mean that sort of tip,” said Dermot, with an indulgent smile; “I mean a financial tip. I suppose you don’t know much about investments?”

“Not a thing,” confessed Roland. Candour would, he felt, be best in the circumstances. No use attempting to bluff with Master-Minds.

“Put your money,” said Dermot, sinking his voice to a cautious whisper, as though he feared that the very walls might hear and make public the priceless secret, “put every penny you can afford into Wildcat Reefs.”

He leaned back in his chair with the benign air of, say, the Philosopher who has just imparted to a favourite disciple the recently-discovered secret of the Elixir of Life. A pregnant silence hung for a few moments over the room.

“Thank you very much, Mr. Windleband,” said Roland, when the overmastering sense of gratitude with which he was filled would allow him to speak. “I will.”

Once more were the Napoleonic features lightened by that rare, indulgent smile.

“Not so fast, young man,” he laughed. “Getting into Wildcat Reefs isn’t quite so easy as you seem to think. Now—how much did you propose to invest?”

“About thirty thousand pounds.”

Roland tried to mention the sum in a casual, off-hand way, as though it were a mere nothing; but the effort was not a success. A note of pride would insist upon creeping into his voice.

“Thirty thousand pounds!” exclaimed Dermot. “Why, my dear fellow, if it got about that you were going to buy Wildcat Reefs on that scale the market would be convulsed.”

Which was true enough. If it had got about on ’Change that anyone was going to invest thirty thousand pounds in Wildcat Reefs the market would certainly have been convulsed. The House would have rocked with laughter. Wildcat Reefs were a standing joke—except with the unfortunate few who still held any of the shares.

“The thing will have to be done very cautiously,” Dermot went on. “No one must know. But I think—only think, mind you—that I can manage it for you.”

“You’re awfully kind, Mr. Windleband,” murmured Roland, gratefully.

“Not at all, my dear boy, not at all. As a matter of fact, I shall be doing another pal of mine a good turn at the same time.”

“Another pal!” Gratifying words, these, from a Master-Mind. Roland felt that he was coming into his own apace. Few young fellows of his age, he was pretty certain, could count Windlebands amongst their friends.

“This pal of mine,” Dermot proceeded, “has a large holding of Wildcats. He wants to realize in order to put the money into something else, in which he is more personally interested. But, of course, he couldn’t unload thirty thousand pounds’ worth of Wildcats on the public market.”

“No, no—I quite see that,” assented Roland. Dermot glanced up at him quickly, wondering whether, after all, he knew a little more than he had appeared to do. Luckily, Roland was trying, at the moment, to look intelligent, so Dermot was reassured.

“It might, however, be done by private negotiation. I daresay I could manage it for you; and probably I could do the deal on very favourable terms. Very possibly—as he wants the money in a hurry—he might let you have the shares at as low, say, as one and a half. I’m not sure, mind you; but it might be done.”

“What do Wildcats stand at now?” inquired Roland, timidly. Dermot smiled at him, pityingly.

“They’re never quoted,” he replied. “There’s no market in them, you see. In the ordinary way nobody ever sells Wildcats. I don’t suppose a hundred pounds’ worth have changed hands in the last six months.”

All of which, again, was perfectly true.

Then Dermot read Roland an article on Wildcats in The City Eagle—a financial organ with which Roland was unacquainted. As Dermot had had to pay one hundred pounds for the article in question he was to be excused for the enthusiasm with which he spoke of the writer’s gifts and of the high opinion in which he held his judgment. From what was said in the article Roland rather gathered that, compared with Wildcat Reefs, the Bank of England was a risky concern in which to put one’s money.

Two days later Roland Bleke became the proud possessor of twenty thousand one-pound shares in the Wildcat Reef Gold-mine, and Dermot Windleband gave his bank a glad surprise by paying in thirty thousand pounds to his account.

It was not, perhaps, till four days later that Dermot again came back from the City with the worried look. Mrs. Windleband could not understand it. Never—even in the most desperate crises—had she known the Napoleon of Finance to look in the least perturbed. She wondered what could be the cause.

When Dermot told her—which he did while they were dressing—her eyes grew big with horror. She could not believe it.

“Good heavens!” she exclaimed. “You can’t mean it! Dermot—I’ve known you to do silly, almost inexcusable things in your time; but this—this—is positively criminal!”

Her husband winced at the words, but he did not attempt to deny the justice of her accusation.

“If he sees the papers in the morning——!”

“He mustn’t! He sha’n’t!”

She walked restlessly up and down the room, trying to think of a plan.

“We must try and keep it from him—for to-morrow, at least,” she said, at last. “Go up to town by the early train—he won’t be down—and take all the papers with you. While you’re away I’ll try to think out something.”

“You’re a dear, sweet soul.”

He made as though to embrace her; but she pushed his arm away, almost roughly.

“Don’t!” she cried. “I couldn’t bear to kiss you, when I think of what you’ve done.”

Dermot bowed his head meekly before the storm of her indignation.

“I—I’m awfully sorry, Lal,” he stammered, brokenly. “I had no idea——”

“Stop! Stop!” she interrupted. “Be quiet. Let me think how on earth I’m to get you out of this ghastly mess you’ve landed us in.”

“Mr. Bleke—don’t go. I want to speak to you.”

Roland stared in astonishment at his hostess. Never before had he seen Mrs. Windleband exhibit the slightest sign of anything that could be construed as agitation. She had always struck him as the calmest woman he had ever met. Nothing ever ruffled her. But now she looked pale and anxious. There were great dark rings under her eyes, which were red, as if she had been crying.

“Please shut the door—and make sure that none of the servants are about.”

Roland obeyed her, wondering what in the world it all meant.

“Mr. Bleke,” she began, in faltering accents, when he had come back to the tea-table, “promise me—on your word of honour—that you will never speak to a living soul of what I am going to tell you.”

Roland gave her to understand that, compared with him, the tomb would be a chatterbox.

“Mr. Bleke—I don’t know how to tell you—but my husband has swindled you!”

The poor woman’s distress, as she made the hateful confession, was pathetic to witness. Agitated and shocked as Roland was by the disturbing intelligence which she had just imparted, his heart was filled with pity for her.

“Swindled me? Your husband swindled me, Mrs. Windleband! I can’t believe it.”

“Neither could I, at first—when he confessed it to me,” came the reply, in heart-broken accents. “But it’s only too dreadfully true. He told me last night, and, Mr. Bleke, I haven’t known a minute’s peace since. I cried all night; and this morning I made up my mind that I must let you know everything and—and try to make what reparation I can!”

Mrs. Windleband’s further utterance was choked by a storm of sobs. Whilst he had every sympathy with her distress, Roland wished Mrs. Windleband would not take her husband’s delinquencies quite so much to heart. Without any desire to hurry her unduly over her lamentations, Roland felt a pardonable anxiety to know how—but perhaps more particularly of how much—he had been swindled by her villainous husband.

Presently Mrs. Windleband recovered sufficiently to explain:—

“It was over those shares he sold to you—those Wildc-c-cats! They’re worthless!” And then there came a fresh deluge.

Wildcats worthless! Roland’s heart stopped beating.

“Oh, Mr. Bleke, forgive him, please!” pleaded Mrs. Windleband, holding out her clasped hands in a gesture of entreaty. “You don’t know how he was tempted. People were pressing him for money on every side—he has so many enemies—he didn’t know where to turn—ruin was staring him in the face! And then, when you came along with all that money at your disposal—it was t-t-too much for him!”

“Can’t quite see that,” was Roland’s rueful reply. “If it was too much for him, why couldn’t he have left me some of it, instead of taking pretty well every shilling I’ve got?”

“How much did you pay for the shares?” asked Mrs. Windleband, ignoring Roland’s last remark.

“Thirty thousand pounds—that’s what he had out of me for them,” said Roland, bitterly.

“Oh, thank Heaven, thank Heaven!” cried Mrs. Windleband, in accents of heartfelt relief. For his part, Roland could see nothing whatever to thank Heaven for; and he said so.

“Ah, but if it’s no more than thirty thousand pounds, I can put everything right again,” explained Mrs. Windleband, joyfully. “Or very nearly, at all events.”

Thirty thousand pounds, it occurred to Roland, was a little matter which would take some putting right. He felt some curiosity as to how Mrs. Windleband proposed to do it.

“Why, I have some money of my own, you see,” she explained. “I wouldn’t let Dermot have it, though he begged me ever so hard, because I wanted to have something secured for us to live on, in case the worst came to the worst. But I would rather part with my last penny and die in the gutter than have Dermot dishonoured!”

With trembling fingers she drew out of her bag a cheque-book. Then she sat down at the writing-table and proceeded to make out a cheque.

“I shall have to post-date it about a month,” she said, apologetically, to Roland, “to give me time, you know, to realize the securities in which my money is invested. Do you mind?”

“But, really, Mrs. Windleband, I can’t allow this,” protested Roland. “It is too generous of you. You must not beggar yourself for your husband’s sake. After all, I bought the shares with my eyes open——”

“If you don’t let me buy them back from you I shall go mad and probably kill myself,” declared Mrs. Windleband, hysterically. “I should never know another minute’s happiness as long as I lived, if I did not right the wrong which my husband has done to you.”

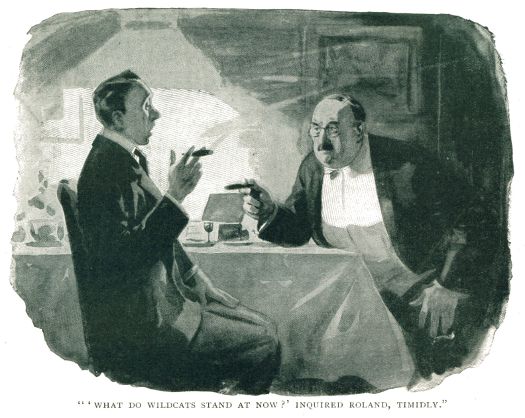

She signed the cheque and, tearing it out of the book, handed it over to Roland.

“If you will just give me some sort of receipt, saying that this is for shares which you will have transferred to me as soon as the necessary documents can be signed, that will make an end of the whole dreadful business, and my mind will be at rest again,” she said.

For just one second Roland hesitated—but only for one second. Then he handed the cheque back.

“I can’t take your money, Mrs. Windleband, really I can’t,” he said, simply. “It’s noble and generous in the extreme of you to offer to make this sacrifice, but I can’t accept it. I’ve still got a little money left; and I’ve always been used to working for my living, anyhow. I—I—can’t tell you how I admire you—but tear this up, please.”

“Mr. Bleke—I implore you!” She had flung herself on her knees before him and was making frenzied efforts to thrust the cheque back into his hands.

This was the moment selected by Parkinson, the impeccable butler of the Windleband establishment, to enter the room. The scene which met his eyes may have surprised Parkinson, but no trace of this betrayed itself upon his calm, immobile features. In his hand he had an evening paper, which he gave to Roland.

“The paper which you asked me to get for you, sir.”

That was all he said. And then he withdrew.

“Parkinson told me he was going down to the village this afternoon, so I asked him to get me an evening paper,” explained Roland, apologetically. “I wanted to see how the Test Match was going.”

He was just about to throw the paper carelessly aside—for who, at a moment of such dramatic stress as that through which he was just passing, wanted to read about Test Matches?—when a flaring headline which ran right across the front page arrested his eye.

“Why!” he exclaimed. “It says something here about Wildcats!”

“Does it?” Mrs. Windleband’s voice sounded strangely dull and toneless. Her eyes were closed and she was swaying to and fro, as if she were just about to faint.

Roland had not over-stated the case. There certainly was something about Wildcats. Indeed, there was hardly anything about anything except Wildcats. Even the Test Match was relegated to the back page.

This was what the headlines alone had to say:—

the wildcat reef gold-mine.

another klondyke.

frenzied scenes on the stock exchange.

brokers fight for shares.

record boom.

unprecedented rise in prices.

Shorn of all superfluous adjectives and general journalistic exuberance, what the paper had to announce to its readers was this:—

The “special commissioner” sent out by the Financial Argus to make an exhaustive examination of the Wildcat Reef Mine—with the amiable view, no doubt, of exploding Dermot Windleband once and for all with the confiding British public—had found, to his unbounded astonishment, that there were vast quantities of gold in the mine.

The publication of their expert’s report in the Financial Argus had resulted in a boom in Wildcat Reefs the like of which had never before been known on the Stock Exchange. In less than two days the one-pound shares had gone up from something like one shilling and sixpence per bundle to nearly ten pounds a share, and even at this latter figure people were literally fighting to secure them.

As she read the pregnant news over Roland’s shoulder, Mrs. Windleband burst once more into expressions of gratitude to Providence.

“Oh, thank Heaven, thank Heaven!” she cried, hysterically. “Then my Dermot was not swindling you after all! He must have known all the time that the shares were going to rise like this. He said something about it when he told me that he had sold the shares to you, but I didn’t believe him. I thought it was only an excuse. Oh—how I have misjudged my poor dear darling!” She dabbed pathetically at her weeping eyes. “I feel so happy, so relieved, that I must go to my room and have a real good cry!”

Roland made no effort to deter her. He was too dazed to do anything. So far as his reeling brain was capable of mathematical calculation he figured that he was now worth about two hundred thousand pounds. It was an awesome thought.

Down the corridor Mrs. Windleband ran into her husband—just returned from the City. He looked at her, inquiringly. She shook her head.

“No go!” was all she said.

But Dermot said a great deal more than that.

[The most original and surprising use which Roland Bleke makes of his sudden acquisition of wealth will be told in the June number.]

Editor’s note:

Cinquevalli: Paul Cinquevalli (1859–1918), German-born juggler, active in England from 1885 until the First World War

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums