Vanity Fair, June 1917

ON CERTAIN PHASES OF THE DRAMA

A Review that Deals With Thackeray, Brandy, the Barrymores and a Knife

By P. G. Wodehouse

THE sensation, occurring so frequently in the life of a dramatic critic, of attending a theatrical performance in a spirit of animosity and bloodthirstiness and then discovering that the piece is fine and that all the caustic things he intended to say about it will have to be thrown away, is akin to stepping on the last stair when it isn’t there.

It jars the lad. It confuses him.

This has just happened to me in regard to “Colonel Newcome” at the New Amsterdam. In the first place, the night before I went to see it I had been to the opening performance of “The Very Minute” at the Belasco, and I felt I never wanted to see a play again. In the second place, I had distinctly given instructions, when reviewing that awful “Major Pendennis” conglomeration of bad writing and bad acting, that no more dramatizations of Thackeray’s novels must be given in this city. It was with a sullen growl, therefore, that our hero might have been observed shuffling to his seat on the night of April the eleventh, 1917. But, scarcely had we deposited the old kelly beneath the feet of our right-hand neighbor and given our left-hand neighbor the Wodehouse Spring overcoat to trample on, when the charm of Sir Herbert Tree’s Colonel gripped us completely. A masterly performance, full of je-ne-sais-quoi and what not. In his long career Sir Herbert has seldom done anything finer.

Michael Morton, who made this dramatization more than ten years ago, has done a better job than did Langdon Mitchell with Pendennis. Things drag terribly whenever the Colonel is off the stage, but, as he is on most of the time, that does not so much matter. It is only in minor details that the lover of Thackeray is entitled to grumble. As, for instance, in the first act, where Clive throws the glass of wine at Sir Barnes. In the novel Barnes has been making a corner in offensiveness all through the scene and thoroughly deserves to have wine administered externally: but in the play it is the Marquis of Farintosh (excellently played by Charles Coleman) who does all the heavy work, Barnes only stepping in at the last moment to receive the juice. The consequence is that one feels a certain measure of sympathy for Barnes. It’s all wrong, Michael, it’s all wrong.

GEORGE HORACE LORIMER, in “Jack Spurlock, Prodigal,” speaks of a certain play as the kind you take two drinks after, quick, and then a third, slower. And in one of W. W. Jacobs’ stories, Ginger Dick and Sam Small go to a temperance lecture, illustrated by magic-lantern slides, and are overcome by such a raging thirst at the sight of the Awful Example draining pot after pot of four-ale that they have to rush out prematurely to quench it. “The Very Minute,” at the Belasco, is just such a play, and it would have had precisely the same effect on Ginger and Sam as that temperance lecture. When you tell people who have not seen it that it is the worst play ever put on the stage, they smile tolerantly and say that it surely can’t be worse than its predecessor at the same theatre. But it is. It has the same relation to the drama that the Cherry Sisters had to the lighter branch of the stage. It is dull, prosy, immature, repetitious, and footling. It is an undramatic tract. Its only interest lies in the fact that it establishes Arnold Daly as the world’s premier catch-as-catch-can absorber of toast-and-water (or whatever it is actors drink on the stage, when they are supposed to be inhaling brandy). It is amazing, the way that man shoots it over the larynx. The only time he pauses for a moment is when his Christian Science uncle works the hypnotic eye on him.

There is a struggle then, but you can’t stop a confirmed toast-and-water fiend with a look: you need dynamite. At the end of the play the hero is supposed to reform; but, as he has already reformed twice previously, only to slide off the wagon with a thud, the presumption is that, if there were a fourth act, he would be starting all over again.

But there are only three acts. The management guarantees that in writing.

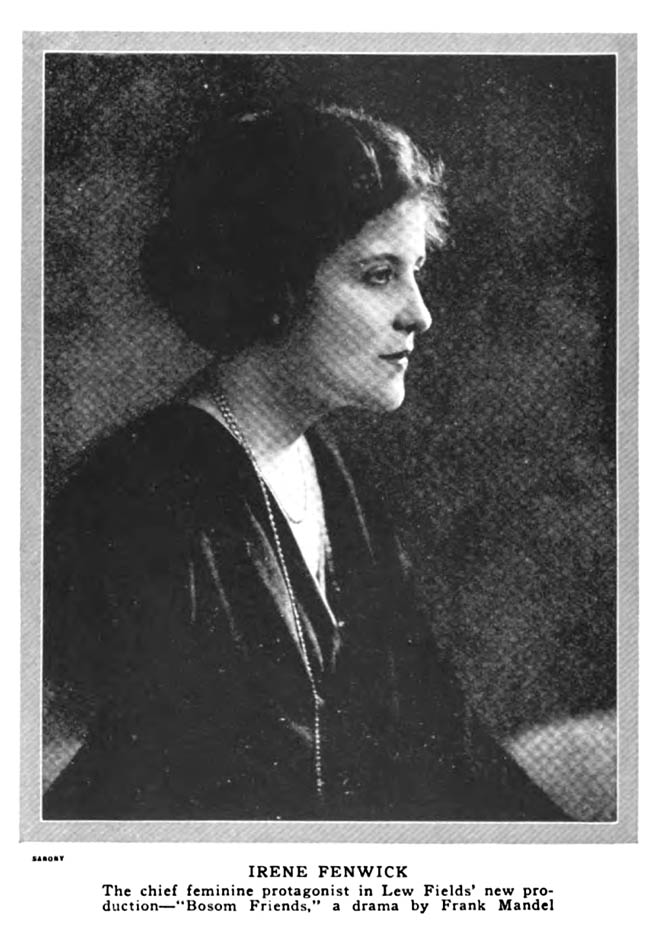

OF “Bosom Friends,” at the Liberty, one critic says, “It moves jerkily.” Later in his review he says, “Mr. Fields has surrounded himself with stars.” The second remark explains the first. These all-star productions are simply cruelty to dramatists. After about a week of rehearsals the author “moves jerkily,” too. You see him on Fifth Avenue being helped across the road by the traffic policeman.

On Forty-second Street he pulls himself feebly along by the railings. If you speak suddenly to him, he bursts into tears. Everyone who has had anything to do with musical comedy knows the small-part actor who sidles up and says that it will be a disappointment to his friends if he comes into New York with so little to do, and can’t a scene be written in for him somewhere in the middle of the big situation.

In an all-star play every member of the cast does this. You must write in a bit for Jones, because Jones has such a big following: and then you must write in bits for Smith, Brown, and Robinson, because you have written in a bit for Jones. And, when you have written in all these bits, you find that you have omitted to provide bits for a couple of bit-lizards whom you have overlooked. And you are expected to combine all this with a straight, snappy, smooth story. Writing the Follies, where every performer brings his agent to rehearsals to help him fight, must be bad enough, but nothing compared to writing a straight all-star play.

Taking this into consideration “Bosom Friends” is a triumph. The story is interesting, the pathos pathetic, and the humor magnificent. Frank Mandel is probably the ablest exponent of what is technically known as the “character” laugh. He has provided these in great quantity for “Bosom Friends.”

Lew Fields, in his first serious rôle, scores heavily. It is no mean feat to induce an audience to weep when it is expecting you to poke your finger in a friend’s eye or otherwise manhandle him. Mr. Fields has had bosom friends in other productions, but he has usually expressed his affection by squirting them with soda or trying to push a shaving-brush down their throats. But the cognoscenti, the nibs, we thoughtful observers who keep our eyes open, have always realized his possibilities for pathos. There was a minute in that go-as-you-please entertainment, All Aboard,—he was a poor sailor, if you recollect, robbed of his savings,—where he simply wrung the heart.

TALKING of wringing hearts brings us to “The Knife.” This bright little piece, which opened the new Bijou Theatre, beats all Eugene Walter’s previous efforts in that direction. It is not so much a thriller as a snorter. If you like torture and nervous breakdowns and white slavers and human vivisection, do not miss “The Knife.” Here is an extract from a morning paper’s review: “The doctor wants to kill the two miscreants, but then he hits upon the happier scheme of using them for experimental purposes.” The word “happier” strikes one as particularly happy. Pretty cheery for the miscreants, what? At the end of the scene “the reluctant offerings to science are being carried struggling to the laboratory.” And, believe me, until you have seen reluctant offerings to science struggling as they are carried to laboratories, you don’t know what struggling is. Mr. Alexander Woollcott thinks that this is a “fearful thing to ask an audience to accept,” and I agree with him. I like a bit of blood with my drama, and I realize that, if your dramatist wants to buy the baby new shoes, he has got to work the Pity and Terror business (an expensive Classical education enables me to drag in Aristotle without an effort), but this picking on miscreants like this is just a shade too much for me. Mr. Walter is a ruthless writer. He has no mercy on an audience.

“The Knife” will either be the biggest success of the season, or it will end swiftly. It is not one of those plays which will do a half-and-half business. It is either so thrilling that everybody will go to see it or so horrible that everyone will stop away. Yet whoever stops away will miss some remarkably fine acting.

AS you travel on rural railroads, you sometimes see out of the window pathetic notices that read, “Don’t Judge the Town from the Depot.” They ought to put up a notice outside the Republic Theatre, “Don’t Judge the Play from the First Night,” for “Peter Ibbetson,” the late John Raphael’s twenty-year-old dramatization of Du Maurier’s best novel, had enough trouble at its opening performance to kill a dozen plays. The piece depends largely on its trick scenery, and the idea of the producers was that, whenever Peter fell asleep and began to dream, the background would melt silently away while another set shimmered softly into its place. On the opening night the background melted about as silently as a boiler-shop, and so reluctantly that great chunks of it remained cluttering up the stage during the ensuing scene. By this time, of course, everything is running smoothly, and the play has a chance to make good.

It is chiefly worth seeing for a wonderful performance by Lionel Barrymore, the Man Who Came Back after twelve years’ absence from the stage. Jack Barrymore is very fine in the murder scene. If the stage-hands keep dropping scenery on him, as they did on the first night, there will probably be more than one murder scene at the Republic.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums