Vanity Fair, December 1916

OUR SLACK AND SLOTHFUL PLAYWRIGHTS

The Broadway Stage Is Cluttered Up with Dramatized Novels

By P. G. Wodehouse

IT was, I believe, the Earl of Hardcastle in “The Man from Home” who criticized America on the score that it was a country without a leisure class. To which Mr. Hodge replied that his lordship had evidently not become acquainted with the colored section of the population. If he had been speaking today, he might have added playwrights to his list, for, believe me, those boys take it pretty easy in this year of grace. A playwright nowadays is not a man who writes plays, but a man who dramatizes novels. The good old custom of getting a central idea and adding to it original characters and a plot—all out of your own head—has practically died out. The modern dramatist is too proud to work. Thinking makes his head ache, so he just loafs through life waiting for someone to write a novel or a short story with dramatic possibilities. Then he chops it up into acts, puts in a few lines to fill out, and instructs Mr. Rumsey to draw up a contract calling for five per cent on the first five thousand, seven and a half on the next fifteen hundred, and so on: and the next thing you know you are jumping for the sidewalk to get out of the way of his new Rolls-Royce.

EXAMINE the current list of attractions. (Call them that for the sake of argument). What have we? I will tell you, as James J. Morton used to say.

Hudson Theatre—“Pollyanna.” Dramatized Novel.

Playhouse—“The Man Who Came Back.” Dramatized Short Story.

Longacre—“Nothing but the Truth.” Dramatized Novel.

Punch and Judy—“Treasure Island.” Dramatized Novel.

Cohan’s—“Come Out of the Kitchen.” Dramatized Novel.

Astor—“Bunker Bean.” Dramatized Novel.

Cohan and Harris—“Object—Matrimony.” Under grave suspicion of being founded on short story.

Belasco—“Seven Chances.” Dramatized Short Story.

Harris—“Under Sentence.” Founded on a Short Story.

Criterion—“Major Pendennis.” Dramatized—if you can call it that—Novel.

48th Street Theatre—“Rich Man, Poor Man.” Dramatized Novel.

WITH the exception of musical plays, two of which are musical versions of old farces, the only non-hash ventures are “Turn to the Right,” “Upstairs and Down,” “Backfire,” “Cheating Cheaters,” “Hush!” and “Arms and the Girl.” It is, so to speak, a bit thick.

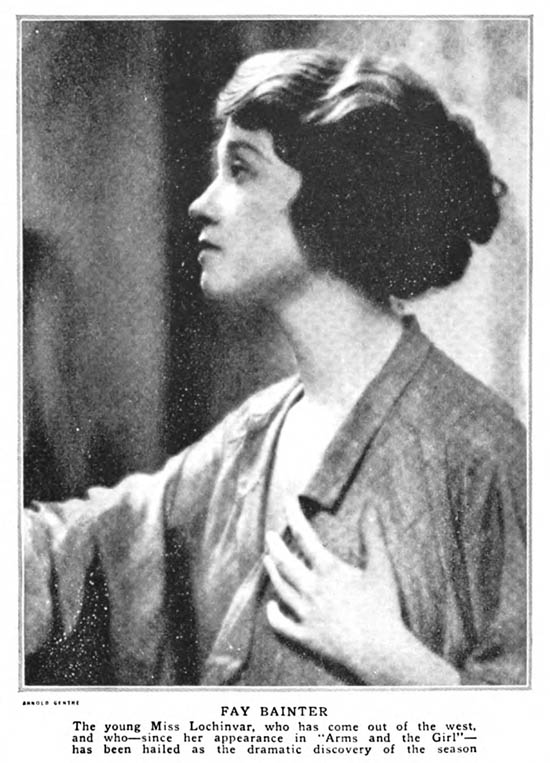

That it is possible for a playwright, if he gets another playwright to assist him and devotes to resolute thinking part of his nightly pinochle time, to turn out a real play is proved by “Arms and the Girl.” In any season this little comedy would have been a gem, but in the arid desert of the present one it stands out like an oasis full of diamond mines. It has the proud distinction of being the only production except “Turn to the Right” which one would voluntarily see again. It has the best central idea of any of the season’s plays, and enough situations to equip half a dozen farce-comedies in these anaemic times. It serves also as the means of introducing to Broadway Miss Fay Bainter, and even “Backfire” might have been forgiven if it had done anything as good as that. Miss Bainter’s advent from nowhere and her instant success form the season’s biggest sensation. The unknown actress leaping into fame in a single night is a favorite theme with writers of fiction, but it does not often happen in real life. Miss Bainter has arrived with the sensational suddenness hitherto monopolized by understudies in the all-fiction magazines,—those fortunate girls who are called on to play the star’s part at five minutes’ notice, and, by Jove, who should be in front that night but Heywood Sherwin, the great critic of the Manhattan News!

“ARMS AND THE GIRL,” by Grant Stewart and Robert Baker, has so congested the Fulton Theatre that the night I went the best the management could do for me was to allow me to hang by my eyelids from the roof. But even a bird’s-eye view of this comedy is better than aisle seat, Row C, at most other theatres. There is a zip and speed to “Arms and the Girl” which is—I mean are—irresistible. And dramatic suspense? It is one solid chunk of d. s. from start to finish.

Cyril Scott, looking about twenty-one, is at his best after his long absence from Broadway. There is no one who can be so satisfactorily breezy, and the part of Wilfred Ferrers gives him every chance. Henry Vogel’s German general is certainly one of the best half-dozen pieces of acting of this season, and Ethel Intropidi, J. Malcolm Dunn, and Francis Byrne are all as good as they can be.

If A. E. Thomas, as he probably has done by now, takes a large blue pencil and uses it vigorously on the first two acts, leaving his third act untouched, “Come Out of the Kitchen,” supported by Miss Ruth Chatterton’s large following, will almost certainly be a success. At present it is played too slowly and is much too long, but it is undoubtedly the sort of thing that people will like, if they like that sort of thing. A city which has swallowed “The Cinderella Man” and “Pollyanna” can swallow “Come Out of the Kitchen.” But it must be speeded up. The story is a farce story, and the only result of trying to play it as a comedy is to accentuate its improbabilities. The last act is excellent. Harry Mestayer is the best of the team.

THE enjoyment of the sort of stories Montague Glass writes and the sort of plays which are based on his stories is so much a matter of personal taste that to criticize “Object—Matrimony” is more of a waste of time than criticism usually is. Nobody can deny that this latest exposition of Jewish life in New York is funny. The only question to be decided is whether you are satisfied merely to laugh, or whether you like humor with a touch of charm to it. “Object—Matrimony” is totally free from charm. Its characters are of the earth, earthy. A primrose by the river’s brim a simple primrose is to them, uninteresting as having no commercial value. Not even on the school of plays where the hero is perpetually opening telegrams from people who want to give him large sums for his soap or his non-intoxicating beer does the shadow of the dollar-bill brood so heavily as it does on “Object—Matrimony.” It is practically a dramatization of Hard Cash. The Secretary of the Treasury ought to be drawing royalties from it. But, sordid as it is, it compels laughter, like all Montague Glass’s work. It misses, however, the appeal of “Potash and Perlmutter.”

A MODERN dramatist will do pretty nearly anything rather than work; but one of the things which he might well shrink from is the dramatization of “Pendennis.” There simply is not a play in the novel, and it is useless to try to extract one. You can do one of two things with that masterpiece. You can either take the character of the Major and invent an entirely new plot round it, or you can take the book and chuck a sort of Irish stew of it onto the stage and trust to the fame of the novel to bring success. Mr. Langdon Mitchell has adopted the latter and easier way. “Major Pendennis,” at the Criterion, is the sort of play which one acted in the nursery, when one dressed up and played at being people in one’s favorite book. There is no dramatic action of any sort. It is a jumble of scenes.

I wish people wouldn’t do this sort of thing. It is so absolutely unnecessary. There are hundreds of books to dramatize without committing mayhem on Pendennis. I am just about due to read it again for the nth time, and, when I do, the memory of the Criterion performance will rise between me and the printed page like an amateur illustration. With the exception of Miss Alison Skipworth’s Lady Clavering, there was not a single character in the play which approximated to the pictures I had formed in my mind. Nothing will convince me that Major Pendennis was not a little, perky, fussy man. John Drew made him heavy and rather sinister. And the Fotheringay, stolid and monosyllabic, becomes in the play a mere babbler. The whole point of Emily Fotheringay, as Thackeray drew her, was that she was practically an automaton. Bows had taught her the tricks of acting, and she went faithfully through the movements when on the stage, but directly she was in her home again she became herself, unable to speak except in words of one syllable. In “Major Pendennis” she is the tragedy-queen even in the garret.

THACKERAY, of course, is the most difficult of all the great novelists to dramatize, but the task of dramatizing any great novelist is one from which anybody capable of earning an honest living in other fields of endeavor might well shrink. Whatever you do, you are bound to be wrong. If you boldly invent dramatic situations which are not in the book, the novelist’s worshippers pile on top of you like a college football team smothering an attempt to buck the line—on the ground that you are committing sacrilege. If you stick to the book, you get a bad play. If I had a son who came to me and said, “Father, I contemplate dramatizing one of the well-known classics and selling the result for much gold,” I would suppress the feelings of a parent and dispose of him with an axe. It can’t be done.

THE best dramatization of printed fiction that there ever has been or ever will be was Sherlock Holmes. Mr. Gillette extracted a bit from one story and a bit from another and shook them up and added a few bits of his own, with the result that, when he married Sherlock off in the end, we felt that even that could be excused to one who had produced such a good evening’s entertainment. Perhaps some reckless person will come along some day and build a play in which Major Pendennis, Becky Sharp, Colonel Newcome, Barry Lyndon, and Dobbin are brought together in one coherent story. The trifling objection that the characters flourished in different periods may be ignored. I am not going to outline the plot—dramatists must do some work for themselves—beyond advocating a love interest between Major Pendennis and Becky Sharp, who would be an ideally happy couple. To give the thing that modern quality known as the punch, it would, of course, be necessary to have Barry Lyndon attempt to steal the Begum’s necklace and be foiled by Colonel Newcome, who would appear as an amateur detective of the Grumpy type and clear Dobbin of the suspicions which had wrongfully been cast upon him. Dobbin in the last act would marry Ethel Newcome, who had believed in him in spite of everything. Amelia Sedley would be an ideal character to secure the support of the matinee girl by playing the “glad” role, and I would use Jos. Sedley as an obstacle between the Major and Becky. The result would be a nice, well-balanced play, full of ginger, and, whatever its demerits, a great more like a play than the one at the Criterion.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums