Vanity Fair, April 1918

The Barrymores, and Others

The New Plays and the Old Players

By P. G. WODEHOUSE

THE last time I raised the Wodehouse hat—it is being condemned on all sides, but the public will have to stand it like men till the straw-hat season begins—the last time, I say, I raised that venerable wreck as a tribute of admiration and esteem for an actor was when Fred Stone came to town in “Jack o’ Lantern.” In the past week I have doffed it twice again, once to Ethel Barrymore, the other time to Lionel Barrymore. There is no gainsaying the fact that these Barrymores are considerable histrions.

Lionel is the one that fascinates me most. He is like the pea under the thimble. Now you see him, and now you don’t. He pops up and makes a sensational success, and then he thinks he has earned a vacation, so he knocks off for ten years or so: and then, just when you think you are never going to see him again, up he bobs once more and makes everybody else look like enthusiastic amateurs reciting pieces at church sociables.

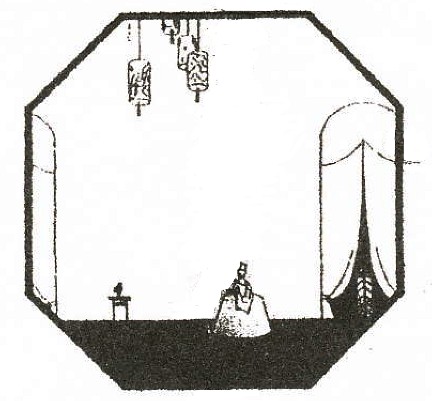

His latest manifestation is in Augustus Thomas’ new play, “The Copperhead,” and as a piece of remarkable acting, it eclipses anything he has ever done in his life.

I remember, in one of Jerome K. Jerome’s books, there is a story of a small-part actor who made such a success on the opening night of a play that, every time he showed signs of “exiting,” the audience got up in a body and implored him not to leave them.

I felt like doing the same thing at the Shubert Theatre, especially in the third act. When Barrymore picked up his hat and announced that he was going to the village, my heart sank, for the Barrymore-less sections of the first two acts had told me only too plainly what was likely to occur if he left the stage: it would simply mean that the other characters sat about and chatted in a dispirited sort of way till he came back. I have never seen a play which died in its tracks so dismally as did “The Copperhead” in the intervals between the Barrymore scenes. The fierce rush of modern life has no doubt left me blasé, for I just could not get all worked up over the discussions about the heroine’s prospects of landing the job of village school-teacher. She was a nice girl, but somehow it seemed to mean almost nothing in my life whether she became a school-teacher or not. The only other scholastic appointment I have ever taken so little interest in was that job of Arnold Daly’s in “The Very Minute.”

“THE Copperhead” is an irritating play. Just as you are getting interested in it, you suddenly skip forty years and are introduced to an entirely new set of characters. The last act is, however, excellent, being practically a monologue for Lionel Barrymore. The curtain on the first night did not fall till a quarter past eleven, which gives the author a quarter of an hour to play about with in the matter of cuts. He should instantly start in and commit a little frightfulness on the early portion of Act III. Let him cut out a quarter of an hour there. Anywhere will do. He can’t go wrong. Sharpen up the old blue pencil, Augustus, and go to it.

Of the other parts in the piece, nearly all are well played. Doris Rankin was admirable in the first two acts as Milt’s wife, and quite good as the rather colorless granddaughter of Acts III and IV. Chester Morris could not have been better in the “bit” of Sam Carter.

R. C. CARTON, whose latest comedy, “The Off Chance,” Ethel Barrymore has chosen as the first vehicle for her starring season, has a curious bias towards the dingy side of life, which he sometimes redeems by his sense of humor and sometimes—as in the present case—fails to redeem. “Mr. Hopkinson” and “Lord and Lady Algy” were both saved by being extremely funny; but the laughs in “The Off Chance” are few and the dinginess rather overpowering. Everybody in it is either divorced or getting divorced, or else they are card-sharpers or adventuresses.

It must be admitted that the card-sharper, as played by Edward Emery, is a lovable character and so inexpert at his trade that he becomes almost respectable; but the atmosphere of the piece is stuffy and uninspiring. Ethel Barrymore is wonderful in a part which gives her no real help. Her playing is an object-lesson in what can be done by a clever woman with very little material. She is assisted by quite the best company in town, including Cyril Keightley as a dejected Duke, Lyall Swete as a rather disreputable peer, Eva le Gallienne, as the young Duchess, and John Cope, as an American millionaire.

THE trouble about “Youth,” the first attempt of the Washington Square Players to give the public a long play instead of their customary susurration of one-act pieces, is that, while long in quality, these wild Washington Square bohemians do not seem to understand that a mercenary public demands quantity as well. It behooves these high-foreheaded, long-haired geniuses who float dreamily above the world in a world of their own, to realize that we earthly devils, when we pay out two crackling bucks, plus the unavailable war-tax, demand two-and-a-half hours’ entertainment. The curtain rises on “Youth” at nine o‘clock (though advertised to whiz up at 8:45) and sinks for the last time at ten minutes of eleven. There are two quarter of an hour intermissions. Mathematicians among my readers will therefore be enabled to figure out that the actual entertainment covers a mere hour and twenty minutes, which is pretty poor recompense for two dollars and twenty cents, earned by the sweat of the brow.

This state of things is all the more maddening in that it would have been perfectly easy for the author to have added quite half an hour to his first act without boring the audience. The atmosphere of “Youth” is that of “The Show Shop,” and people who like that sort of thing can stand that sort of thing indefinitely. I, personally, would have been content to sit in my orchestra chair and watch Ferris, the assistant stage-manager, buzz about the stage for hours.

Even in “The Show Shop” the atmosphere of behind the scenes was not depicted with such fascinating knowledge. Every detail was true to life. These Washington Square Players certainly know how to act. Arthur Hohl’s performance could not have been improved upon by anybody. And the grouchy stage-carpenter was wonderful. Just what Miles Malleson, the author, was driving at was a little hard to make out; but nevertheless I enjoyed every minute of “Youth.” It seems a revolutionary thing to do in advise an author to add instead of cutting, but I strongly urge Mr. Malleson to write in some more of his excellent stuff in the first and second acts and give us a full evening’s entertainment instead of a mere skeleton of one.

I HAVE the honor to report that, by executing a brilliant strategic retreat to Palm Beach, I hope to make my fortune at the expense of the Beach Club. I have an infallible system.

So I missed seeing “The Little Teacher.” I know it is a wonderful success and all that, but it is one of my fixed rules of life to give the inflexible raspberry to all plays and novels which deal with the adventures of rural school-teachers who spread light and sweetness and eventually marry the cow-boy or the lumber-jack. I know that Mary Ryan must be splendid in her part. She would be. But for me the purer pleasure of getting into the Beach Club’s ribs for a few hundred per day.

AND now you will want to hear all about “Oh, Lady! Lady!!” at the Princess. Well, it seems pretty nearly all right. Disappointed mobs howl outside the doors each night, as they are clubbed away by the police. I wouldn’t recommend the piece if I had not a large financial interest in it, but, honestly, you ought to pawn the family jewels and go and see it, if only to reward Guy Bolton and myself for the work we put in on it on the road. You wouldn’t believe the number of semi-human excrescences who told us during the tour that the show would never “get over” in New York, and advised us, as friends, to throw away our second act and write an entirely new one.

And now it is a big success. Well, well! James, call up the Rolls-Royce offices and order another car for us.

Tell them that we liked their last one very much.

Note: Karen Shotting suggests that “unavailable war-tax” is a typesetter’s error for “unavoidable war-tax”; this makes sense.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums