Vanity Fair, January 1916

THE “GREAT WHITE WAY” FRAUD

The Most Flagrant Sham of Modern Times

By P. G. Wodehouse

IN these days of the movement for the encouragement of honesty in advertising, when patent medicines cannot raise their heads without having them bitten off by Samuel Hopkins Adams and when a merchant who, in a moment of absent-mindedness, labels the hide of a deceased cat “genuine sealskin” is exposed next morning in large print, it is astonishing that none of our Vigilance Committees have thought of attacking the most colossal fraud of them all. I allude to Broadway.

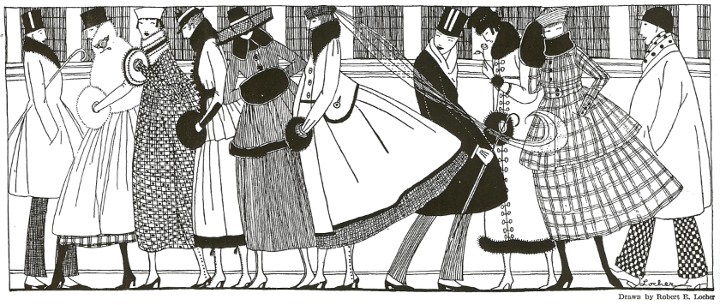

A stranger who had never visited our beautiful little city and had derived his information about it solely from what he had heard or read, would undoubtedly imagine that Broadway was so nearly the whole of New York that the rest was not worth mentioning. Fraudulent advertising is responsible for this. If a street goes about the place calling itself The Great White Way, naturally it takes you in. You picture a broad and noble thoroughfare, blazing with light, a long vista of magnificent buildings, along which pace well-dressed men and smart women, mostly sirens. Paved with marble, probably. Perhaps Broadway gets like this somewhere up by Two Hundred and Ninetieth Street, but it certainly does not in the late thirties and the early forties. It is amazing that nobody has written to the Tribune about it.

OUT of justice to other, less advertised streets—good, honest, hard-working streets, which never get boomed—it is time that somebody made a protest. The way in which Broadway takes the credit for their achievements makes the blood of a just man boil. You never hear anyone singing “There’s a Little Street in Heaven They Call West Thirty-ninth Street.” You read in the theatrical column in the daily paper that such-and-such a play is to have a Broadway production; and when you look more closely into the matter, you find that it is coming on at the Candler Theater or the Cort.

It is in this matter of theaters that Broadway’s bluff is most easily exposed. Why, so far from being the theatrical center, Broadway can’t even support its own theaters, and even its restaurants are shaky. What has happened to the Bijou? How is Wallack’s making out? We don’t hear much of the Café Madrid these days. How about the Café de l’Opera? The Knickerbocker is a motion-picture house. So is the New York Theater. And yet, when a real live street like Forty-second puts on a show, Broadway smirks modestly, as if it were responsible for the whole thing.

FORTY-SECOND Street seems to have the greatest grievance against Broadway. For years it has been looked on as a mere satellite of the latter. People were hypnotised into speaking of “Broadway and Forty-second” as if the only bit of Forty-second that had any claim to notice was the bit that ran across Broadway. Yet look at it now—full of restaurants which make you pay all you’ve got before they will even let you talk to the hat-check boy, and theaters which sizzle with electric lights and success. Forty-eighth Street is another that has grounds for complaint. It isn’t even near Broadway—it adjoins Seventh Avenue. In the most plucky and spirited way it went into business on its own account, built theaters, spent money on kilowatts or whatever they call them, and put on expensive plays. Yet, if “The Princess Pat” is still with us twelve months from now, it will be said to have run a year on Broadway.

One of the worst results of this fraudulent advertising is the effect it has on the youth of out-of-town districts. Take the case of Lemuel P. Terwilliger, of Nineveh, Pa. I hate to think of it. Lem was the desk-clerk at the Hotel Superbe. (It’s that wooden place that looks like a tool-shed as you go down Main Street on the right-hand side, leaving the postoffice and the drug-store behind you.) He was only eighteen when the first craving to see the Great White Way seized him. Drummers and traveling actors would infest the hotel and speak long and earnestly to Lem about the magnificence and allurements of Broadway till they turned his head and he began to save his money for one visit to that thoroughfare of bliss and luxury. When his contemporaries spent their nickels at the soda-fountain or blew in dimes, taking girls to the movies, Lem sat in his bedroom counting his money. He was not going to waste his substance on the tame pleasures of a country town; he meant to reserve himself for Broadway.

Time went on. The rush of social life at Nineveh left Lem stranded. He got the name of a recluse. Some even called him a tightwad. But Lem knew what he was doing. In a few more years, saving at this rate, he would be able to make the trip and have one real, regular rip-snorting time among the bright lights of that earthly Paradise, the Great White Way.

He was thirty-two when he achieved his ambition. As he strolled out of his hotel, dressed in an eighteen-dollar dress-suit as worn by the King of England, John McGraw, and Diamond Jim Brady, he thought with a certain pity of the benighted state of the friends he had left behind him. There was a fudge and progressive hearts party on tomorrow, to which all that was best and brightest in the Younger Set of Nineveh intended to flock, and they had wanted him to stop on for it. He laughed at the notion. He strolled on until he come to a dingy street paved with wooden planks and smelling of gas, and then he asked his way to Broadway. He was informed that this was it.

IT was rather a shock to Lem, but he supposed that this was a part of it which was a trifle less great and white than the rest, so he walked uptown. He dined sparely at the Automat, had his photograph taken at the place where they polish you off and give you the results while you wait, and after that he was rather at a loose end. He began to think that there must be some mistake, and that this could not really be Broadway. There seemed to him nothing in the mean-looking theaters with their unimposing entrances, the chop-suey restaurants, the music-shops with their display of vulgar post-cards, and the moving-picture houses to justify the name of the Great White Way. It was about this time that a sense of something missing came upon Lemuel with renewed force. For a moment he was puzzled, then he realized what was wrong. He could see no sirens. It was part of his most firmly settled beliefs that Broadway was congested with sirens, that, if you threw a brick on Broadway and failed to hit a siren, it was only because your aim was unbelievably bad. He looked north, south, east, and west, but not a siren could he see. An aching desolation came upon him. Jostled by depressed-looking men in dingy suits, he was beginning to feel conspicuous in his evening-dress. People looked at it and at him with a curiosity which they made no attempt to conceal. Some held that he was on his way to a fancy-dress ball, others that he was going about like this to settle an election bet.

Gloom surged upon Lem. He became desperate. He stopped a passer-by.

“Is this really Broadway?” he asked.

The passer-by could not deny it.

“The Great White Way?”

The passer-by said that it was.

“Where are the sirens?”

The passer-by had never heard of them.

EARLY next morning a train pulled out of the Pennsylvania Station. It contained, among other passengers a care-worn man who seemed to be deep in thought. From time to time he raised his right leg and kicked himself. This was when he thought of all the good times he had denied himself for the last fourteen years in order to see the Great White Way.

I have told Lem’s story because it is one of which I have first-hand knowledge; but he is merely one of many thousands of deluded young men who visit New York every year on the strength of what they have heard about the Great White Way. This thing must be stopped. It is opposed to the entire spirit of honesty in advertising that Broadway should be permitted any longer to pose as the dickens of a place. It is not great, and it is very far indeed from being white.

But already there are signs of better things. The other day a good deal of Broadway collapsed and hid itself. The experts talked a lot about rock-slides, but what really happened was that it did it in a spasm of pure shame. Broadway just tried to go into a hole and pull the hole in after it.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums