Vanity Fair, January 1917

THE NEW PLAYS OF THE OLD YEAR

The Playlet Indeed is the Play

By P. G. Wodehouse

HAVING scored a touchdown in Forty-First Street after such a short period of bucking the line, the Washington Square Players may be said to have made good with astonishing rapidity. In fact, in a welter of plays—good, bad, and simply awful—their advent at the Comedy Theatre stands out as the chief theatrical event of the later season of 1916. At their third attempt they have established themselves, and are doing business which many a low-browed manager with a chewed cigar in the corner of his mouth and a squad of dramatic fixers on the leash, might envy. It must be very pleasant to be a Washington Square player these days, for there are few more delightful things than to uplift the public and make a profit out of it. The catch about uplifting, as a rule, is that people won’t come and be uplifted; but go wandering off to places like the Century and the Winter Garden which, whatever their merits, do not jack up the soul. It should always be remembered that, in order to do any uplifting, one needs a little human material to lift up.

THE secret of the success of the Washington Players’ present season is due to the fact that their bill is amusing and entertaining, as well as uplifting. In fact, if you were not warned on the programme that you were witnessing the work of “a group of actors, artists, and authors interested in stimulating and developing new and artistic methods of acting, producing, and writing,” you might think that you had just happened to stray into a theatre where there was a rather good show on. With the exception of the first piece, “Trifles,” a somewhat monotonously sombre playlet of dark and dreary doings in the Middle West corn-belt, the entire bill could go into vaudeville and do well. Lawrence Langner’s comedy, “Another Way Out,” would be a success anywhere. It deals with an aspect of the marriage question which is about the only one Shaw has overlooked in “Getting Married,” and is excellently played by Helen Westley, Robert Strange (as good a book agent as the stage has seen), Gladys Wynne, and José Ruben.

IN a perfect theatrical world, of course, there would be nothing—or very little—except quadruple bills. Instead of allowing authors to expand their one-act ideas into three-act plays, after the manner of the mediæval torturer who used to put a five-foot citizen on a rack and turn him into a six-foot citizen, managers would insist on brevity. What a quadruple bill could have been made of “Cheating Cheaters,” “Nothing But the Truth,” “Seven Chances,” and “The Basker.” At present any dramatist who needs the money is allowed to come along and try to make you believe that he is giving you a two-dollar evening’s entertainment with a play whose action is laid—Act I: Sir Reginald Whoosis’ rooms. Act II: The Same, a few moments later. Act III: The Same (Twenty Minutes Have Elapsed). Sometimes, with a sort of infantile cunning, he shifts the third act to the Conservatory of Lady Whoosis’ Boudoir, but he can not disguise the fact that what he is handing to a trusting public is really a one-act play, violently lengthened like a piece of fresh molasses candy.

AND in Japan, it would appear, things are even worse. Bushido, the one-act play at the Comedy, was designed by its authors to start at six in the morning and finish at six p.m.; for the frugal Japanese does not consider that he has had his money’s worth out of a theatrical entertainment unless he charges in at the door, bolting the bacon and eggs of an unfinished breakfast and gets out just in time for dinner. When you want to drop into a show in Tokio, you set the alarm-clock for 5.15 and say good-bye to your friends overnight. “Bushido” is enthralling in its Forty-First Street form, but it might begin to drag a bit around about four in the afternoon, especially if you had forgotten to take sandwiches with you and couldn’t get out for a bite of lunch.

WHILE on the subject of one-act plays and the uplift, I must earnestly beg one and all not to miss “Getting Married.” William Faversham may have done better things than his Bishop of Chelsea, but it has not been my privilege to see him do them. Actors in Shaw’s plays suffer from the same handicap as those who play parts in dramatized versions of classic novels, for most people read Shaw before they see him on stage, and the actor has either to be similar or superior to the audience’s preconceived notions of what the various characters are like. I am glad to be able to tell Mr. Faversham, Miss Crosman, Mr. Harwood, Mr. Fitzgerald, Mr. Cherry, Miss Hackett, Mrs. Gurney, Mr. Hare, Mr. Dillman, Miss Brooks, Mr. Cushman, and Mr. Belmore,—(they have few pleasures, and this will brace them up like a tonic)—that I approve of their efforts. They are all right.

“Getting Married” may not be Shaw’s best play, but it is so much better than anybody else’s—or, writing for a refined and intensely educated circle of readers, should I say—‘anybody’s else’ best play that that does not matter much. At any rate, Collins and General Bridgenorth are two of the best characters that the whiskered marvel of Adelphi Terrace ever drew, and they could not be better played than they are by John Harwood and Lumsden Hare. Arleen Hackett was particularly charming as Leo, the girl who, though divorcing her husband, still took a motherly interest in him and made him wear his liver-pad instead of using it as a kettle-holder.

THAT I enjoyed “Old Lady 31,” Rachel Crothers’ dramatization of Louise Forsslund’s novel, in spite of the fact that two ghastly creatures in more or less human form in the seats behind me made running comments in a loud voice throughout, and in spite, also, of the fact that nearly all through the first act Vivia Ogden rocks violently in a rocking-chair (which always makes me sea-sick), shows, I take it, that there is good stuff in the play. Emma Dunn’s performance of Angie is certainly one of the best individual performances of this season or the last,—if not the best. Her voice alone is worth considerably more than the price of admission. It is almost a waste of effort to give her good lines to speak, she needs them so little. As Abe, her husband, doomed to spend his declining years in an Old Ladies’ Home, Reginald Barlow does the best work of his career. He is perfect. The play itself depends on its atmosphere rather than on its action, which is a trifle sluggish. It has more character parts in it than any comedy that was ever produced, I should imagine, and all so well played that it is almost impossible to name one—except Miss May Galyer’s Blossy, a sort of septuagenarian Billie Burke—that stands out above the others. Marie Carroll, who was good in “Rolling Stones,” is good in a part where she has nothing much to do except look young and pretty, but does that little well. A visit to “Old Lady 31,” if you are one of those rugged cave-men who can look a rocking-chair squarely in the eye without feeling as if the ship had run into a white squall, is an absolute necessity. Do it now.

THE apparent deadlock in the Broadway trenches has broken up since I last wrote a piece for this periodical, and prevented the photograph of Mrs. Vernon Castle colliding with the dog-advertisements. At that time the gloomiest rumors were current. The promoters of “Back-Fire” seemed determined to fight it out on those lines if it took all winter: and all over the theatrical zone the spectacle was seen of managers with obvious failures baring their teeth in ugly fashion and daring anybody to take their theatre away from them. It almost began to seem that Heywood Broun was right, and that the only way to get rid of some of these plays was to beat them to death with sticks. Brighter times, however, have dawned, and many of the old inhabitants have been shunted off, with the result that—at the present writing—three new plays, “Captain Kidd, Jr.,” “The Thirteenth Chair,” and “Our Little Wife,” have managed to squeeze in. Of these I have so far only seen the last, and, gosh darn it! it is from all accounts the only bad one of the trio.

Avery Hopwood is in the unfortunate position of having to top “Fair and Warmer” every time he writes a racy farce. He would be a wiser man if he steadied the public with a melodrama or a tragedy or something before he took up farce-writing again. His trouble is that he insists on writing pieces of the same genre as that triumphant success, and it is impossible not to be disappointed when they suffer by comparison. There was an elusive quality about “Fair and Warmer”—its name was almost certainly Madge Kennedy—which he was not able to recapture in “Sadie Love” and misses by considerably over a mile and a half in his present play. Margaret Illington is not the right heroine for a Hopwood farce. She smiles bravely, but she is not happy in the part of Dodo Warren, the maintainer of tame cats. Also, the central idea is weak. The redeeming points of “Our Little Wife” are Walter Jones and—decidedly more so—Robert Fischer, whose Waiter in the second act, technically only a “bit,” is raised by his acting almost to the rank of a star part.

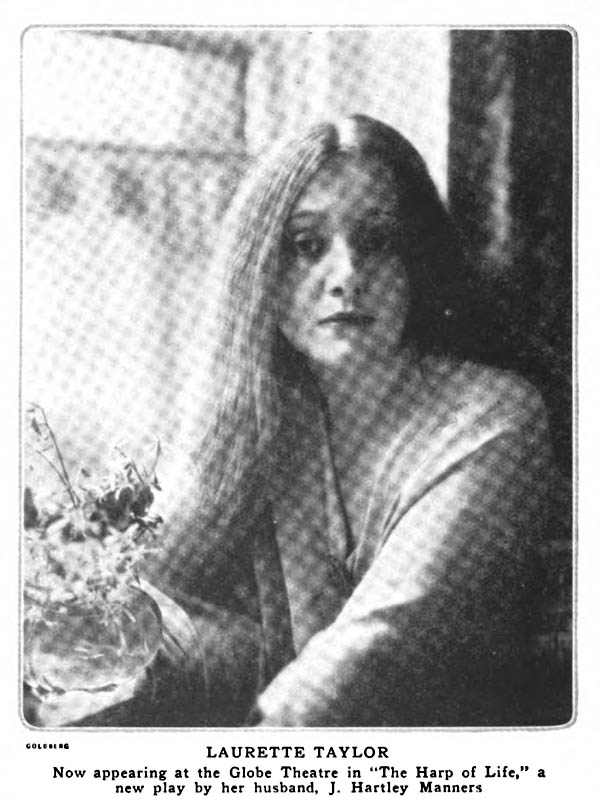

I SUSPECT Mr. J. Hartley Manners of being one of those diabolically clever people who keep an eye on the trend of things and watch public movements and so on. He has observed that mothers are very much to the fore just now—possibly he has seen “Turn to the Right,” read the Evening Journal, or heard Miss Eva Tanguay warble that affecting ditty, “M-o-t-h-e-r”—so he thought that a play about mother-love could not go wrong, even though it forced Miss Laurette Taylor to act the part of a woman of thirty-six instead of the Peg of our hearts. Whether “The Harp of Life” at the Globe will go wrong, I do not know; but if it succeeds it will be in spite of the worst last act in captivity. I doubt if the most sentimental will be able to swallow that last act. It has the same effect on the play that a blow with what the papers always call “some blunt instrument” has on the citizen who receives it behind the ear. This is all the more distressing as, for two acts, though her delivery tends to be a little monotonous, Miss Taylor has gripped the audience in a firm grasp. Lynn Fontaine, a newcomer on Broadway, does excellent work as the girl whom the son temporarily jilted for the adventuress whom the mother squelches in the last act.

Note:

The Internet Broadway Database confirms that the “newcomer” in the last sentence was indeed Lynn Fontanne, whose only prior Broadway credit had been in a short run in 1910.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums