Vanity Fair (US), December 1914

THE PLEASURES OF DUELLING IN GERMANY

By P. G. Wodehouse

WHATEVER else of significance the Great War in Europe has had for the thoughtful man, the point of greatest interest in it has been the extraordinary toughness of the German Crown Prince.

It was, if we remember rightly, in the first week of hostilities that he began being killed, and, once started, he has kept bravely at it ever since. It is now no rare experience for him to be killed three times in a single day, and in localities distant from each other several hundred miles.

Now it is obvious to the meanest capacity that only the most rigorous training in early youth could have given him this superb Teutonic stamina. An American, reared only on college football and homemade pie, would have expired at his first or second death. At the outside, dissolution number three would have set his friends to buying immortelles and to relating stories of how kind he had always been to animals. The difference in the case of the Crown Prince was that he was trained on the mensur, or German student’s duel. General Von Kluck’s favorite pastime as a boy was a go-as-you-please mensur.

If you can survive it, you can survive anything—from a bursting shell to a course in German kultur. Anybody can go through an ordinary duel but imagine surviving the following ceremonies on a hot summer evening.

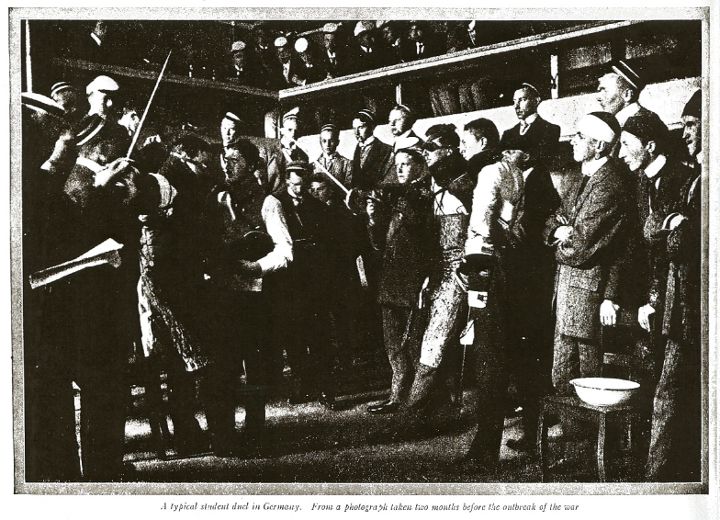

The student first dons a shirt and trousers of white cotton. Over these his dressers place a huge leather coat, and on this they buckle a padded sleeve and a collar four inches high. A leather eye-guard is the next item, covering the eyes, the nose and the forehead. The poor fellow then puts on a large, thick glove, and the preparations are nearly complete. Having done all this to the human junk-shop, his so-called friends lean him against a chair. They look at him thoughtfully. There must be something else they can do to make dear old Wilhelm look a bigger fool, but for the moment they cannot think what it is. They then chalk the palm of his glove and the soles of his feet and finally, they rub grease on his eye-guards. That seems to finish the thing. Nobody can think of anything else, so they put a sword into the poor fellow’s hand, introduce him to another walking dummy, get out a couple of china wash basins, to catch the blood, and then tell him to go in and chop bits off his adversary, which—as far as his what-the-well-dressed-man-is-wearing-this-season costume will permit—he proceeds to do, and the mensur has begun.

FOUR blows make a ging: sixty gings make a mensur. It sounds like an extract from a table of distances, and you would expect it to continue, “Five mensurs make one rod, pole or perch”; but the ging turns out to be only another name for what we call a “round” in boxing. A great point about the student duel is that both principals must hit at exactly the same time. Other rules are that they must not move either foot or head, must not parry, and must not feint. It would not be German if there were not a whole lot of things that were forbidden. In fact, there seems to be so little that they may do, beyond gashing their cheeks, that the thought irresistibly occurs, to the non-German reader, that a great deal of time and trouble would be saved if these earnest young men were given ordinary safety razors and told to shave themselves. We are no duellist, but only this morning, when we were getting our beard under control, we gave ourself a schlaegerstroke which would have made the biggest kind of a hit in a ging.

THIS duelling is not a casual affair. You cannot run into the kitchen for a meat-axe; into the bedroom for a pair of pillows; into the garage for the chauffeur’s motor-goggles, and then go out and begin vivisecting your fellow-man. That would not be complicated enough for Germany. The whole thing must be carefully systematized. There are two types of duelling associations which have their branches in every German University. This enables the restless student to leave his nose in Heidelberg, his right ear in Göttingen, and a sliver of his chin in Düsseldorf—thus combining the pleasures of travel with the delights of a barroom argument.

ATTACHED to each University duelling club is a verein. A verein is—how shall we put it?—Perhaps it can best be described as a verein. It is a place where the students, when they are not duelling, sit around and sing college songs. Naturally a man who has spent years in listening to college songs holds life less dear than one who has been through no such perils. Anyone who has ever sat on the porch of a Summer hotel while four or five sophomores were singing “Boola-Boola”—in close harmony—will heartily endorse this statement.

Note:

mensur: Karen Shotting suggests that a fuller, if somewhat gruesome, explanation of mensur can be found in Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men on the Bummel (1900), chapter XIII. We know that Wodehouse was an admirer and reader of Jerome, so this may indeed be a principal source for this piece.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums