Windsor Magazine, April 1903

CUPID AND THE PAINT-BRUSH.

By P. G. Wodehouse.

Marjorie was sitting under the cedar on the tennis-lawn. It seemed to me that the best way of spending my morning would be to go and sit under the cedar on the tennis-lawn, too.

“Good morning,” I said as I came up. I had seen her before, but “Good morning” is such an excellent conversational gambit.

“Good morning,” said Marjorie. She marked with a finger her place in the book she was reading, and tried to impress me with the idea that she was busy, but could give me two minutes if I had something of exceptional importance to say.

I declined to encourage this absurd attitude. I took away her book kindly but firmly, laid it down on the grass out of her reach, and began.

“Marjorie,” I said.

From constantly playing Juliet to my Romeo, Marjorie has developed a habit of reading my thoughts, which at times I find distinctly inconvenient.

“I should make you wretched,” she said.

“Not at all,” said I politely. “Besides, what are you doing now but making me wretched?”

“You don’t know what I’m like, really, or you wouldn’t——”

“Persevere? Of course I should. I know much better than you what’s good for you. Think how much older I am. We were made for one another.”

Marjorie appeared to ponder.

“Say the word,” I added encouragingly. Marjorie and I have known each other since I was in sailor suits.

“You’d hate the sight of me in a couple of years,” said she.

“By that time you would adore me so passionately that you wouldn’t notice it. I am an acquired taste; but once acquired, never lost.”

“You know it wouldn’t do, really.”

“May I ask why on earth not? I wish we could manage this affair without argument. I hate arguing.”

“So do I.”

“Then why argue? Agree with me—and all shall be forgiven.”

“Will it make you conceited if I tell you something?”

“Impossible.”

“Well, it isn’t you I object to. It’s the being married at all—just yet.” The last two words were added as a species of afterthought.

“Now, that is a concession. My suit, then, I take it, is practically smiled upon?”

“I knew it would make you conceited.”

“Not at all. Merely natural gratification. What is your objection to marriage in the abstract? Tell me the worst. Are you a woman with a mission?”

“Well, I suppose I am, in a way. I want to paint.”

“But——”

“I knew you would say that. Don’t be silly. I mean paint pictures, of course. You shouldn’t twist people’s meanings. It’s a very bad habit. Will you please pass me my book?”

I deliberately moved the inconvenient volume still further out of the way with my foot. Such a request at such a moment was simply impertinent, and I ignored it.

“Will you give me my book, please?”

“No. Couldn’t you go on painting when you were Mrs. Me?”

“Of course not. I should get lazy.”

“We could work together. I also am an artist of peculiar merit.”

“You?”

“Decidedly. You didn’t see the comments of the Press on my last year’s Academy picture, then?”

“No. Did you?”

“No. That, however, was simply because there was no such picture. Painting, however, is a game which two can play at. Do you know what my initials are? R. A.”

“Well?”

“Well, if that is not an omen, what is an omen? Tell me that. Now, look here, Marjorie, we are going to make a sporting bargain. We will each paint a picture for the Academy this year, and whoever paints the better one has his or her (it is not likely to be her) way in the matter. Do you agree?”

“Who is to judge?”

“We will buttonhole the President and get his private opinion. Only you must not sign your name, of course. These Academicians, you know, they’d give the verdict to a lady without a second look. Now do you agree?”

“Very well. It’s very silly.”

“Silly! Good gracious! It’s a life and death matter to me. That is all I want to say. You may now go on reading that very worthless book. I’ve lost your place.”

Marjorie left next day. A fortnight later I met her in town. I was coming down the steps of my club, and our ways, by some extraordinary coincidence, happened to lie in the same direction.

“How does the picture progress?” I asked. “Personally I have chosen an allegorical subject. I call it ‘Waiting.’ ”

“That is original.”

“Isn’t it? Originality is quite a hobby of mine. I intend to represent a beautiful young lady dressed in a neat creation of white, standing on a rustic bridge with her back to a rather sweet thing in Turneresque sunsets.”

“I see. And how does the title apply?”

“She is supposed to be waiting for a gentleman to whom she is devotedly attached. He is at present not in sight. But in one corner of the canvas an angel form, in whom the acute observer will readily recognise Fame, heralds his approach with a few notes from a gold trumpet. An expression of intense but natural gratification shines on the face of the beautiful young lady.”

“I suppose so.”

“And how is yours getting on, and what is it to be?”

“I am painting a landscape.”

“With figures?”

“There’s a cow in one corner.”

“Nothing else?”

“No.”

“Then I feel secure. The President, wavering between the merits of our respective landscapes, will remember my beautiful young lady, and the thing will be done. I see him at this moment, his face one large expanse of admiration.”

“Indeed?”

“Yes. Now perhaps, under the circumstances, you would like to retire from the contest and acknowledge my superiority?”

“I shall do nothing of the sort. I don’t believe you are painting a picture at all. I don’t believe you can paint.”

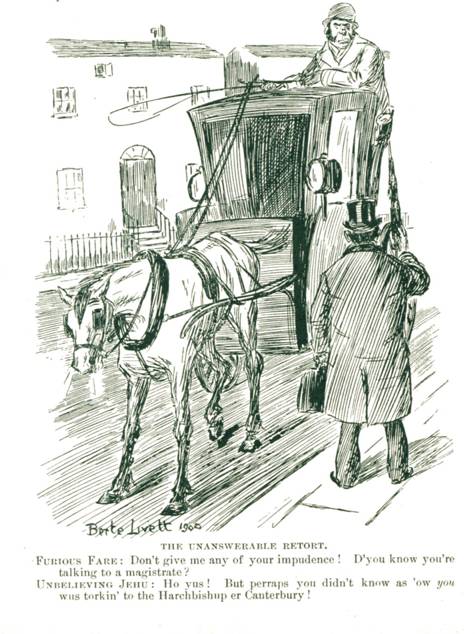

“Good morning, Miss Somerville,” I said. “After that, you will hardly expect me to speak to you. Here we are at your door, and I will take my wounded self off in a hansom.”

Sending-in day came and went, and one morning I called at the Somervilles’ and asked to see Marjorie. The butler thought she was in the drawing-room. The rest of the family were out, but she had stopped at home. Should he tell her that I had called? I said that there was no necessity to announce me. I would go to the drawing-room.

I knocked steadily at the door for three-quarters of an hour (it may have been less) and then went in. At first the room seemed empty. Then I noticed a limp form on the sofa. It was Marjorie, and she was crying. I can stand a good many things, but one of the things which I cannot stand is to see Marjorie cry. She started up as I came in, and endeavoured to mend matters with a wholly inadequate pocket-handkerchief.

“I did knock,” I said. “Marjorie, do tell me what’s the matter. Has the picture been rejected?”

“Yes.” A sob from the sofa.

“Never mind. We’re both in the same——”

“I see now how silly I was ever to think I could paint.”

I caught my own eye in the mirror and winked affectionately at it.

“Marjorie,” I said, placing a hand in hers—always a sound move—“we will forget that idiotic wager. Treat me as if I had never asked you before, and tell me that you’ll—will you?” At this point it seemed judicious to remove my hand from hers and slide it round her waist. I did so. She made no protest.

“Marjorie, say ‘Yes.’ ”

“Yes.” In a whisper from the sofa.

After that, several other things seemed judicious, and I did them all. She appeared rather to like it than otherwise.

“Marjorie,” I said, after a long silence, “do you know why I came today? I wanted to ask you to take me in spite of that absurd wager.”

“But you won it.”

“No. It was a drawn game. My allegory failed to impress the Committee.”

“What! You were refused?”

“My picture was. I was accepted. By you. Don’t move.”

She did not move.

Another long silence.

“We’ll take to photography,” I said at last thoughtfully. “Share the same camera and develop off the same plate.”

Marjorie sat up suddenly.

“Do you know,” she said, “I don’t mind so very, very much about the picture. I never did think very highly of the Academy. You know, it’s so—so——”

“Yes, isn’t it?” I said. “Exactly what I have always thought about it. Don’t move.”

She did not move.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums