Company for Henry

or

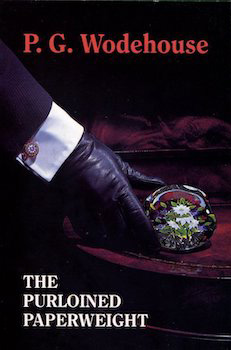

The Purloined Paperweight

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the contributors to Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums to document references, allusions, quotations, etc. in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

These notes were initiated by Ole van Luyn for this site and edited and expanded by Neil Midkiff to begin the annotation project, to which further contributions are welcomed; contact us at the address on the Contact page of the site if you have useful or interesting notes to add, whether a single item or a large set.

The novel initially appeared in a two-part condensed form in the Toronto Star Weekly, April 29 and May 6, 1967, under the title The Purloined Paperweight. The first US hardcover edition was issued by Simon & Schuster, New York, on May 12, 1967, also as The Purloined Paperweight; the UK edition was issued as Company for Henry by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. on 26 October 1967.

The novel initially appeared in a two-part condensed form in the Toronto Star Weekly, April 29 and May 6, 1967, under the title The Purloined Paperweight. The first US hardcover edition was issued by Simon & Schuster, New York, on May 12, 1967, also as The Purloined Paperweight; the UK edition was issued as Company for Henry by Herbert Jenkins Ltd. on 26 October 1967.

The Paperweight Press of Santa Cruz, California, reprinted the Simon & Schuster edition in 1986 with a new introduction by Lawrence H. Selman, a collector of paperweights, in which he explains that Wodehouse was mistaken in describing them as eighteenth-century art objects. They were first made in the nineteenth century, and the type described in the book were produced in France between about 1840 to 1860.

The Paperweight Press of Santa Cruz, California, reprinted the Simon & Schuster edition in 1986 with a new introduction by Lawrence H. Selman, a collector of paperweights, in which he explains that Wodehouse was mistaken in describing them as eighteenth-century art objects. They were first made in the nineteenth century, and the type described in the book were produced in France between about 1840 to 1860.

The Simon & Schuster first US edition is dedicated “To Peter Schwed, best of publishers”; other editions have no dedication.

Page references below refer to the first UK edition, in which the text runs from pages 7 to [222].

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 |

Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 |

Chapter 1

Henry Paradene had begun to scramble eggs in a frying pan (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

Reading between the lines, I [NM] wonder if this may have been one of Plum’s own kitchen attempts. Recall that in “Birth of a Salesman” (Nothing Serious, 1950) Lord Emsworth “had frequently scrambled eggs at school” but makes a mess of it at his son’s home. In any event, it seems probable that Wodehouse preferred his eggs that way (as I do, so I may be biased), as they are so often mentioned:

There was a cold chicken on the sideboard, devilled chicken on the table, a trio of boiled eggs, and a dish of scrambled eggs. I helped myself to the latter, and sat down.

Love Among the Chickens, ch. 15 (1906/09/21)

He hoped to see Jimmy at that meal, and had not forgotten that Jimmy had a preference for scrambled eggs on toast.

The Luck Stone, ch. 35 (1909)

It was wrong, of course, for Paul to slip and spill an order of scrambled eggs down the brute’s coat-sleeve, but who can blame him?

“Rough-Hew Them How We Will” (1910; in The Man Upstairs, 1914)

He pictured the thing in his mind. Breakfast: Elizabeth doling out the scrambled eggs.

Uneasy Money, ch. 19 (1916)

“Breakfast,” said Rupert, firmly. “If you don’t know what it is, I can teach you in half a minute. You play it with a pot of coffee, a knife and fork, and about a hundred-weight of scrambled eggs.”

“The Long Hole” (1921; in The Clicking of Cuthbert, 1922)

“That Hobson woman is beginning to make trouble,” went on Gerald, prodding in a despairing sort of way at scrambled eggs.

The Adventures of Sally/Mostly Sally, ch. 6.1 (1922)

“I’m sitting peacefully in my room at the hotel in Chicago, pronging a few cents’ worth of scrambled eggs and reading the morning paper, when the telephone rings.”

The Adventures of Sally/Mostly Sally, ch. 10.2 (1922)

“We’re good trenchermen, we of the Revolution. What we shall require will be something on the order of scrambled eggs, muffins, jam, ham, cake and sardines.”

“Comrade Bingo” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923)

Baxter, hearing them, gave such a violent start that he spilled half the contents of his cup: and Freddie, who had been flitting like a butterfly among the dishes on the sideboard and had just decided to help himself to scrambled eggs, deposited a liberal spoonful on the carpet, where it was found and salvaged a moment later by Lady Constance’s spaniel.

Leave It to Psmith, ch. 8.1 (1923)

Judson helped himself to more coffee, but declined with a gentle shake of the head and the soft, sad smile of a suffering saint Bill’s offer of scrambled eggs.

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 16 (1924)

“I am now at last in a position to give you the low-down on the Riviera, as based on the observations of self and egg-scrambler.”

Letter to Leonora, March 30, 1925, from Cannes

“Genevieve,” he replied, “has bought one of those combination eyebrow-tweezers and egg-scramblers.”

“The Castaways” (1933; in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere, 1935)

“Don’t you realize that, even under the best of conditions, there’s practically nothing that won’t make a sensitive, highly strung girl break off her engagement? If she doesn’t like her new hat . . . or if her stocking starts a ladder . . . or if she comes down late to breakfast and finds all the scrambled eggs are finished.”

Heavy Weather, ch. 10 (1933)

“The juice of an orange, sir, followed by Cute Crispies—an American cereal—scrambled eggs with a slice of bacon, and toast and marmalade.”

Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 18 (1934)

This had the effect of bucking me up still more, for breakfast in bed is always breakfast in bed, until he went out and reappeared with the tray, and I perceived that all it contained was milk, some stuff that looked like sawdust, and a further consignment of those blighted prunes. A nice bit of news to have to break to a stomach which had been thinking in terms of scrambled eggs and kidneys.

Laughing Gas, ch. 12 (1936)

“I’m sort of wondering,” Mrs Steptoe went on as her guest seated himself after dishing out a moody portion of scrambled eggs, “how to fit everybody in today.”

[…]

“And all this,” said Lord Holbeton, “could have been avoided, if only the woman had taken scrambled eggs. That’s Life, I suppose.”

Quick Service, ch. 1 (1940)

It was open to Lord Shortlands, had he so desired, to start with porridge, proceed to kippers, sausages, scrambled eggs and cold ham, and wind up with marmalade: and no better evidence of his state of mind can be advanced than the fact that he merely took a slice of dry toast, for he was a man who, when conditions were right, could put tapeworms to the blush at the morning meal.

Spring Fever, ch. 19 (1948)

And I had just finished tucking away a refreshing scrambled eggs and coffee, when the door opened as if a hurricane had hit it and Aunt Dahlia came pirouetting in.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 15 (1954)

“No harm in hoping,” said Jane, and went off to scramble eggs.

[…]

“There you are,” said Jane, arriving with laden tray. “Scrambled eggs, all piping hot, coffee, toast, butter, marmalade, The Times and a couple of biscuits for the hound.

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 2–3 (1957)

“So I brought Augustus,” she said, and indicated a large black cat who until then had escaped my notice. I recognized him as an old crony with whom I had often breakfasted, I wading into the scrambled eggs, he into the saucer of milk.

Jeeves in the Offing/How Right You Are, Jeeves, ch. 7 (1960)

These same experts, turning their attention to the other sex, now say that if you are thinking of employing a man in some executive post the way to analyse his character is to note how he likes his breakfast egg.

The poached egg addict, it seems, is “artistic, nervous and passionate,” the fellow who prefers his eggs scrambled, “dynamic, personable and intelligent,” and the five-minute boiled egg man is the determined organizing type, so that unless you object to that nervous passionate stuff you can hardly miss.

Fine so far, but do they go far enough? Nothing, for instance, is said about the breakfaster who regards his scrambled eggs with a calculating eye and then pours the contents of the ketchup bottle over them, a procedure which, if I were an employer, would certainly make me think a bit and wonder if the chap was so personable and intelligent after all.

Our Man in America in Punch, August 17, 1960

Ben Casey (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

Ben Casey was the main character in a popular American television series about an eponymous surgeon, broadcast from 1961 to 1966. When the book was published in 1967 a reference to Casey would be understood by all readers in the USA; even if UK readers had not seen the show, the context makes the allusion clear.

Beau Paradene (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

Wodehouse chose the nicknames of two Regency spendthrifts in imitation of “Beau” Brummel; see Heavy Weather.

Bill, Lord Dawlish, in Uneasy Money, blames his moneyless title on relatives including his Regency ancestor Beau Dawlish, who had “a taste for high stakes at piquet”.

kennel maids (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

This is the only reference so far found in Wodehouse’s fiction to this post, but in a 1943 letter while he was still in a Berlin hotel without his wife, he noted “what with being kennel maid to Wonder I never seem to have a moment.” Wonder was one of the many Pekingese dogs that he and Ethel loved over the years.

wife of a neighbouring farmer of the name of Makepeace (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

Reminiscent of the cottage rented by George Bevan in A Damsel in Distress, built as a rental speculation by a neighboring farmer named Platt whose wife comes to “do” domestic services for George.

gamboge (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

As a noun, describing a tropical gum resin or its color; as an adjective, having the color of it, a “dull or dark orangey or mustard yellow" (OED).

the height of its fever (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

See Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen for the phrase. But this should never apply to scrambled eggs, which should be cooked slowly over low heat to be tender and fluffy. High heat is more likely to make them tough and dried-out than to make them “lumpy” as Jane cautions Henry on the following page.

a well-dressed wood nymph (ch. 1.1, p. 7)

A nice oxymoron, since most artists and illustrators clothe these fairy-like spirits of the forest in very little at all.

Algy (Ch. 1.1, p. 8)

We’ve met Algy Martyn before in The Little Warrior/Jill the Reckless (1920), though with no mention in that book of his sister or uncle.

her brother, a lily of the field who toiled not neither did he spin (Ch. 1.1, p. 8)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Henry had once advanced the theory that the ravens fed him. (Ch. 1.1, p. 8)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Mon Repos, Burberry Road, Valley Fields (Ch. 1.1, p. 8)

As in many books, Valley Fields is a stand-in for the real-life West Dulwich; see Sam the Sudden. Mon Repos appears in Sam the Sudden as a semi-detached house, sharing a wall with San Rafael, the home of Matthew Wrenn and Kay Derrick, but San Rafael is not mentioned in the present book.

obiter dicta (Ch. 1.1, p. 8)

See Money in the Bank.

Park Avenue, New York (Ch. 1.1, p. 9)

From 1949 to 1955, Plum and Ethel Wodehouse had a duplex penthouse apartment at 1000 Park Avenue, New York.

Besides J. Wendell Stickney in the current book, other residents on Park Avenue in books from this period and following include Mrs. Pegler in French Leave (1956), J. J. Bunyan (retrospectively in 1929) in Something Fishy/The Butler Did It (1957), James R. Schoonmaker (at 1000 Park Avenue) in Service with a Smile (1961), Charles Cornelius in Ice in the Bedroom (1961), and Tipton Plimsoll in Galahad at Blandings (1965).

Earlier, Isaac Goble lives there in Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior (1920); Thomas and Josephine Moon and their daughter Ann live there in Big Money (1931).

non compos (Ch. 1.1, p. 9)

See Cocktail Time.

Bread upon the waters (Ch. 1.1, p. 10)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

a sprat to catch a whale (Ch. 1.1, p. 10)

See Heavy Weather.

If you don’t speculate, you can’t accumulate (Ch. 1.1, p. 10)

See Bill the Conqueror.

Duff and Trotter (Ch. 1.1, p. 10)

Provision merchants in London, first encountered in Quick Service (1940) in which co-founder J. B. Duff is a character.

Like Abou ben Adhem, he loved his fellow men (ch. 1.2, p. 13)

“Abou Ben Adhem” is a poem by James Henry Leigh Hunt (1784–1859), based on the spirit of Fraternity. First published in The Amulet (1834), the poem is Hunt’s rendering of a divine encounter between an angel and the Sufi mystic, Ibrahim Bin Adham. See A Damsel in Distress for the text of the poem.

It was as if, like Lot’s wife, he had been unexpectedly turned into a pillar of salt. (Ch. 1.3, p. 20)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

He spoke with something of the smug self-satisfaction of the prophet whose predicted disasters come off as per schedule. (Ch. 1.3, p. 23)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

Algy from childhood up had never modelled himself on the poet’s lark which was accustomed to be on the wing when morn was at seven and the hillside dew-pearled (ch. 1.4, p. 26)

The poet in question is Robert Browning and the poem, from 1841, is Pippa Passes. See Something Fresh for the text and for references to other Wodehouse allusions to it.

Chapter 2

a motion picture star whose face had launched a thousand bags of popcorn (ch. 2.1, p. 33)

“The face that launched a thousand ships” is the original to Wodehouse’s little joke. That face belonged to Helen of Troy, and those words are Marlowe’s who, in his play The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus (1604), has Faustus, who wants unrivalled power, conjure up Helen of Troy, whose beauty indeed launched a thousand ships, carrying the Greek army to wage war on the city of Troy. For the full story: see Homer’s Iliad.

Popcorn consists of puffed grains of maize. Eating popcorn in large quantities, often sold and consumed in cinemas while watching a popular film, originated in the United States in the 1930s.

Some men are born to country houses, some achieve country houses, others have country houses thrust upon them. (ch. 2.2, p. 36)

A Wodehousian variation on Shakespeare’s text in Twelfth Night, where Malvolio reads aloud a forged letter sent to him, designed to turn his head: “In my stars I am above thee; but be not afraid of greatness: some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ’em.” See other Wodehouse allusions to this passage.

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

they say Heaven protects the working girl… (ch. 4.3, p. 66)

Probably from “Heaven will protect the working girl,” a ‘burlesque ballad’ published in 1909:

…She went with him to dine

Into a table d’hôte so blithe and gay,

And he says to her, “After this we’ll have a demitasse.”

Then, to him these brave words the girl did say:

“Stand back, villain! Go your way!

Here I will no longer stay,

Although you were a marquis or an earl.

You may tempt the upper classes

With your villainous demitasses,

But Heaven will protect a working girl.”

A 1914 film borrowed its title from the ballad, but not much more, except that its story also has a girl saved in the nick of time from, as they used to say, a fate worse than death.

[NM:] Wodehouse alluded to this song in his lyric for the title number from the 1916 musical Have a Heart (music by Jerome Kern). A kindly department-store owner takes pity on the lot of the shopgirls he employs:

So I’m making it my mission

To improve her sad condition,

And like Heaven, I protect the working girl.

Chapter 5

in addition to looking like a Tanagra statuette, Jane Martyn possessed all the qualities… (Ch. 5.1, p. 71)

Tanagra figurines were a mold-cast type of naturalistic and often elegant Greek terracotta figurines produced from the later fourth century BC, primarily in the Boeotian town of Tanagra.

his correct soul shivered austerely at the thought of lending his imprimatur to a scheme… (ch. 5.3, p. 90)

Imprimatur is Latin for “let it be printed.” The invention of printing led to the Roman Catholic Church judging which books could be read by the general public and which could not. It gave an imprimatur to the first category. The word has since been generalized, as here, to refer to an approval to let any kind of plan go forward.

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

‘Quoth the raven!’ (Ch. 7.3, p. 123)

From the 1845 narrative poem The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe.

[NM:] Wodehouse alludes to the poetical raven’s reply of “Nevermore” in Bachelors Anonymous, ch. 6.2 (1973), but here Jane’s reference is more to Bill’s role as Elijah’s raven than to Poe’s bird.

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

a nymph surprised while bathing (ch. 9.3, p. 165)

In UK edition only. A nymph surprised (La Nymphe surprise) is a well-known painting by Manet of a young unclad women sitting near a lake in a wooded area, obviously, as the title has it, surprised and trying to hide herself, to not much avail.

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Wodehouse’s writings are copyright © Trustees of the Wodehouse Estate in most countries;

material published prior to 1931 is in USA public domain, used here with permission of the Estate.

Our editorial commentary and other added material are copyright

© 2012–2026 www.MadamEulalie.org.