Bill the Conqueror

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc., in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

Bill the Conqueror has been annotated by Neil Midkiff, with substantial contributions from Diego Seguí [DS] and suggestions from Ian Michaud [IM] and others as credited below. It is a standalone novel with respect to its main characters, although Sir George Pyke (Lord Tilbury) and Percy Pilbeam return in later books.

Bill the Conqueror has been annotated by Neil Midkiff, with substantial contributions from Diego Seguí [DS] and suggestions from Ian Michaud [IM] and others as credited below. It is a standalone novel with respect to its main characters, although Sir George Pyke (Lord Tilbury) and Percy Pilbeam return in later books.

Bill the Conqueror was first published on 13 November 1924 by Methuen & Co., London, and on 20 February 1925 by George H. Doran, New York. It was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post and in the UK Grand magazine prior to book publication; see this page for details of serial appearances. Both magazine serials contain passages omitted from the books; the SEP serial has a very few tiny cuts, and the Grand serial has significant omissions; at present only the initial episode of Grand, corresponding to the first two episodes of the SEP serial, has been transcribed, since it seems less authentic to Wodehouse’s original, for reasons explained in its endnotes. The cuts in the Grand serial are mentioned below only as they affect passages which are otherwise annotated; this document does not purport to describe all the omissions.

These annotations and their page numbers relate to the Doran first US edition, in which the text covers pp. 11–323. For those who are reading other editions, a table of correspondences between the page numbering of several published editions can be seen here.

Title

BILL THE CONQUEROR

His Invasion of England in the Springtime

Diego Seguí points out that the title and subtitle of the book contain a strong allusion to William, Duke of Normandy, who invaded England (but in the autumn, not the springtime), defeating King Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings, 14 October 1066, and then being crowned King of England; in history he is often called just “William the Conqueror.”

Chapter 1

A Marriage Has Been Arranged

Sir George Pyke … Roderick (p. 11)

This is our first glimpse of the newspaper magnate, soon to be known as Lord Tilbury; see the notes to Sam the Sudden (1925) for his real-life antecedent Alfred Harmsworth (Lord Northcliffe). He appears later in Heavy Weather (1933), Service with a Smile (1961), and Biffen’s Millions/Frozen Assets (1964).

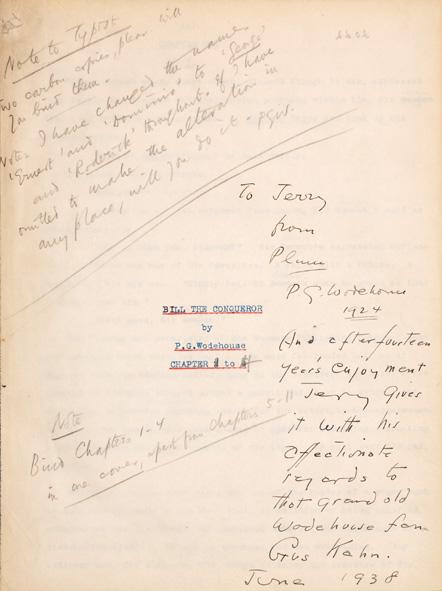

Ian Michaud brings our attention to a bookseller’s listing for the original typed manuscript of the first few chapters of this book, bound and given as a gift to Jerome Kern. A pencil note to the publisher’s typist on the title page (image at right) reads: “I have changed the names ‘Ernest’ and ‘Dominic’ to ‘George’ and ‘Roderick’ throughout. If I have omitted to make the alteration in any place, will you do it. PGW.”

Pilbeam (p. 11)

Another character encountered here for the first time but by no means for the last. We meet him again in Sam the Sudden (1925), Summer Lightning (1929), Heavy Weather (1933), Something Fishy (1957), and Biffen’s Millions/Frozen Assets (1964).

Fleet Street … Tilbury House (p. 11)

Harmsworth (Lord Northcliffe) owned two buildings just off Fleet Street: Carmelite House, from which he issued his newspapers, and Northcliffe House, the home of his Amalgamated Press magazines. Wodehouse clearly created Lord Tilbury with Northcliffe as a model, and as Norman Murphy notes, did not do so until after Northcliffe’s death in 1922, possibly to avoid annoying a powerful man or even provoking a lawsuit; the resemblances are many, including the use of the name of his title for the name of his headquarters building.

[The Grand serial omits this passage, leaving these references to be made later in the novel.]

Mammoth Publishing Company (p. 11)

First mentioned in Something New/Something Fresh (1915) as the publisher of several newspapers and magazines as well as the British Pluck Library for which Ashe Marson writes the adventures of Gridley Quayle, Investigator under the pseudonym of Felix Clovelly. Norman Murphy noted in A Wodehouse Handbook the similarities to Harmsworth’s real-life Amalgamated Press, including Harmsworth’s Pluck Library.

buttons (p. 12)

The uniform jacket of a boy working as a page, messenger, or the like was conventionally decorated with one or more rows of close-set buttons to give a quasi-official, almost military air. See the illustration by A. Wallis Mills of Harold, the page boy at Twing Hall, in the Strand magazine appearance of “The Purity of the Turf” (1922). See also Albert, the page boy in A Damsel in Distress. Diego Seguí notes that in Spanish, a hotel bellboy is called a botones (literally “buttons”).

[The Grand serial omits the passage with the pageboy; this reference has nothing to do with Sir George Pyke’s Napoleonic pose with his right hand at his waistcoat buttons.]

Ilfracombe etc. (p. 13)

As we will see, Sir George has been offered a peerage; Wodehouse is inconsistent on the rank involved, referring to him as a viscount in Sam the Sudden and Heavy Weather, but only as a baron in Service with a Smile and Biffen’s Millions/Frozen Assets. In either case, it is a hereditary peerage that is being offered; other than a few judges ex officio, life peers did not exist until the Life Peerage Act 1958. Most of the fictional peerages in Wodehouse derive their title from British place names, and the list here contains several: Ilfracombe is a seaside resort on the North Devon coast; Barraclough is an alternate spelling of Barrowclough, near Wakefield in Yorkshire; Wensleydale is the valley near Wensley in Yorkshire, famous for a classic cheese; there is or was a Bighton-Woodshot in Hampshire; there is a Micheldever in Hampshire near Winchester. Forshore and Waynscote may be archaic spellings of “foreshore” and “wainscot”; Creeby is a family name. Diego Seguí finds a Marlinghue in a 1922 story by Burt L. Standish.

[The Grand serial omits this passage, mentioning a few of these potential titles later.]

about twenty pounds overweight (p. 13)

By the time of Heavy Weather he is about twenty-five pounds overweight.

[The Grand serial begins with the sentence containing the phrase above.]

Napoleonic (p. 13)

Norman Murphy again fills in the details: Northcliffe was a great admirer of Napoleon, and it is rumored that he chose the title in order to be able to sign himself simply “N” as did the Emperor.

the port of Sir George (p. 13)

The OED classifies this usage of port to mean “deportment, bearing, carriage” as archaic and rare in its online edition (last updated 2006), although (as Diego notes) it is not so labeled in the original 1907 print edition.

How Many Pins Does The Prime Minister’s Hat Hold competition (p. 15)

In a time of expanded literacy and avid competition among newspapers and magazines for the public’s attention and trade, contests with attractive cash prizes were a common publicity stunt in popular publications. The Globe By the Way Book (1908) satirized these; see the section “The Great Puzzles” in John Dawson’s annotated selection of items from the book.

Ian refers us again to Norman Murphy’s A Wodehouse Handbook, in which we learn that Harmsworth’s publishing empire made its breakthrough with an 1899 competition offering one pound per week for life to the person who came nearest to guessing “How Much Money Is There in the Bank of England?”

turn the corner (p. 15)

This phrase, for passing from an unsuccessful to a successful period in business or in health, reminds this Wodehouse reader of Aunt Dahlia’s Milady’s Boudoir in Right Ho, Jeeves (1934):

“Is the Boudoir on the rocks?”

“It will be if Tom doesn’t cough up. It needs help till it has turned the corner.”

“But wasn’t it turning the corner two years ago?”

“It was. And it’s still at it. Till you’ve run a weekly paper for women, you don’t know what corners are.”

Harrod’s Stores (p. 15)

See The Inimitable Jeeves (1923) for a history of the store and of the apostrophe in its name. The Saturday Evening Post serial, in accordance with that magazine’s editorial policy of avoiding real company names, disguises Mr. Shale’s employer as “Beasley’s Stores.”

[The Grand magazine serial omits this passage and Mr. Shale entirely.]

dictaphone (p. 16)

A trademark (1907) of the Columbia Graphophone Company for a wax-cylinder speech-recording device for business dictation; by 1923 the product was spun off into a separate Dictaphone Corporation. Wodehouse uses it as a generic name in lower case, but the Saturday Evening Post serial substitutes “dictating device” here to avoid naming a specific company.

Beaverbrook—Stratheden—Leverhulme (p. 16)

Lord Beaverbrook (Canadian-born Max Aitken, 1879–1964) was a newspaper magnate (the Daily Express, Evening Standard, and others) and politician, knighted and then in 1917 given a peerage for his wartime efforts. Stratheden is the name of a barony in Scotland, now Stratheden and Campbell; the first holder (1836) was a Baroness. The first Viscount Leverhulme was William H. Lever (1851–1925), co-founder of Lever Brothers, a highly successful soap manufacturer, though controversial because of his involvement in the soap trust. See Wodehouse’s 1906 satires “The Soap King’s Daughter” and “The Martyrs” and the annotations in the end notes to both. His title was created in 1922, shortly before the writing of the present book.

blacker than ever (p. 16)

These three words are cut in the SEP serial, among the very few slight cuts in that version.

Lucy Maynard (p. 17)

Ian Michaud wonders if Sir George’s late wife was some relation of Rose Maynard of “Honeysuckle Cottage” (1925). Their personalities seem similar although Rose, unlike Lucy and her son, had blonde hair and blue eyes.

Holborn Viaduct Cabin (p. 17)

This frugal lunch counter is apparently a Wodehouse invention; the viaduct itself is a road bridge in London, built in the 1860s to connect Holborn and Newgate Street in the City of London, spanning the valley of the subterranean River Fleet. Diego finds the Holborn Tavern as a possible influence, although the Viaduct Hotel was advertised as luxurious, not frugal.

do it now … motto (p. 17)

See Leave It to Psmith (1923) for background and mentions of a few of the dozens of uses of this phrase in Wodehouse, many of these capitalized or referred to as a motto or catchphrase.

One of Northcliffe’s editors recounts his use of the phrase in a 1916 newspaper campaign for stronger wartime leadership: “Get a smiling picture of Lloyd George and underneath it put the caption Do It Now, and get the worst possible picture of Asquith and label it Wait and See.” Once again Wodehouse transfers a characteristic of Northcliffe to his fictional counterpart Pyke/Tilbury.

For Asquith and his motto, see The Code of the Woosters.

In some such accents might King Lear have spoken of his children. (not in book)

This sentence appears in both magazine serial texts just before the speech in which Sir George says the next-listed phrase.

gave that boy his head (p. 17)

A phrase from driving a horse-drawn carriage, where “giving the horse its head” means slackening the reins so the horse goes in the direction it wants to go.

Walter Pater (p. 17)

Victorian British art historian and critic; see Summer Lightning for one example of his prose quoted by Wodehouse.

limp purple leather (p. 17)

Wodehouse often describes limp purple and squashy mauve bindings for pretentious publications of his overly-artistic writers and poets. See Leave It to Psmith and a later reference in the present book.

twice-told tale (p. 18)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

imbecile (p. 18)

At this point, the word imbecile was used by psychologists as a technical term for adults whose mental age was that of a child of three to seven, capable of fluent speech but unable to master the written language; for more on this, see Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (1981). Its generic use as a popular term of invective (as in Sir George’s tirade here) and the introduction of IQ scores led to its abandonment by scientists.

female brain is smaller than the male (p. 19)

More fascinating history of the bad science behind this theory is in Gould’s The Mismeasure of Man (see previous note).

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

arbiter elegantiarum (p. 21)

Latin for a judge of artistic taste, first used for Petronius in Nero’s court.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

—the ones which Pilbeam, a jovial enthusiast, had described as the fruitiest of the bunch (p. 22)

This passage is the largest one cut in the first episode of the SEP serial.

Sir George’s frown (p. 22)

In the magazine serials, it is “Sir George’s Jovian frown”; that is, majestic and terrible as that of Jupiter. Not to be confused with “jovial,” an adjective somewhat contradictorily derived from the lighter side of Jupiter’s character or the supposed jollity of those under Jupiter’s astrological influence.

Kempton Park (p. 22)

See A Damsel in Distress.

Lucius Junius Brutus … comfort of his son (p. 23)

One of the founders of the Roman Republic in 509 BC, having helped to overthrow his uncle Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of the Roman monarchy. His own two sons were involved in a conspiracy to return the royal family to power; Brutus became famous for stoically watching their execution.

Ian Michaud reminds us that Nanki-Poo, son of the Emperor of Japan in W. S. Gilbert’s libretto for The Mikado, was claimed in marriage by Katisha, an elderly lady of the court, and that:

My father, the Lucius Junius Brutus of his race, ordered me to marry her within a week, or perish ignominiously on the scaffold.

Diego Seguí notes that Galahad Threepwood tells a somewhat different account of Lucius Junius Brutus’s fame to Linda Gilpin in A Pelican at Blandings/No Nudes is Good Nudes, ch. 9 §2 (1969/70).

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

His voice was like that of a nervous Roman gladiator saluting the emperor before entering the arena. (not in books)

This sentence follows “said Roderick hopelessly” in both magazine serials. Suetonius, in The Twelve Caesars (Claudius, 21), records the gladiators’ salutation Ave, Caesar, morituri te salutant (“Hail, Caesar, we who are about to die salute you!”). Diego reminds us that Jill’s Uncle Chris quotes the Latin before going off to propose to Mrs. Peagrim in Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior.

Wimbledon Common (p. 23)

A large open space of heathland in southwestern London, formerly the the property of the Earls Spencer, but designated in 1871 as public parkland for recreation and conservation. The adjacent private homes are naturally desirable residences; see The Mating Season for a list of Wodehouse characters who lived next to the Common.

alarm and despondency (p. 24)

See Ukridge.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Hamadryad (p. 25)

A divine spirit in Greek mythology, a wood nymph born bonded to a tree.

always this way with girls (p. 25)

It is impossible for your annotator to resist the supposition that Wodehouse was influenced in this description by the maturing beauty of his stepdaughter Leonora, who was eleven when he met her in the spring of 1915, some months after marrying her mother Ethel, and thus would have been about twenty as this book was written. Some corroboration can be found in Alexander Woollcott’s description of her as “that lovely stepdaughter of Wodehouse” in a 1933 letter to Jerome Kern (The Letters of Alexander Woollcott, Viking Press, 1944, p. 117).

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Why should I get up? (not in books)

This question precedes “I refuse to get up for anyone” in both magazine serials.

reseating himself (p. 25)

The magazine serials have a longer conversation following this. Passages omitted from the book text are highlighted in yellow; text omitted from the Grand serial is in dark red type:

“You know, of course, that you are an abominable nuisance, child?” he observed, reseating himself.

“Of course,” said Flick equably. “It’s awfully nice of you to offer me your chair, but I shall be perfectly all right down here on the grass.”

“I wouldn’t give you this chair if you pleaded for it with salt tears,” said Mr. Hammond. “For one thing, you’re only going to stay a moment.”

“I’m not. I’ve come for a nice long talk.”

“Leave me, woman. Get back into your tree, you yellow-haired hamadryad. Can’t you see I’m busy?”

Flick glanced up. She was looking, Mr. Hammond thought, unusually pensive. Her mouth was a little drooped and white teeth showed below her lip. Her blue eyes, which always reminded him of a rain-washed sky, were clouded. This surprised Mr. Hammond, for as a rule she took life lightly.

“Are you really busy, uncle?”

“Of course not. I was just wondering when you came out how I should find a decent excuse for stopping work. Something on the mind, Flickie?”

Flick pulled at the grass thoughtfully.

“Uncle Sinclair, you know you always say you never give advice to anybody.”

“My guiding rule in life. I attribute my universal popularity to it.”

“I wish you would give me some.”

avoided the society of his juniors (p. 27)

In this Sinclair Hammond resembles Peter Pett (Piccadilly Jim, ch. 1), Lord Emsworth (Full Moon, ch. 4 §4 and Galahad at Blandings, ch. 8 §2), and L. G. Trotter (Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 18).

but if Francie endorsed him that settled it (p. 27)

Magazine serials insert here the following dialogue, omitted from book versions:

“Good-looking chap, too.”

“Yes, in a way.”

“Ah,” said Mr. Hammond, bravely trying to keep it light, “I see what the trouble is. Constant association with me has set your standards a little too high. You must be practical, my child. There is only one Sinclair Hammond in the world. You will have to resign yourself to something short of perfection.”

the chap in the Bab Ballads (p. 27)

The title character, Captain Parklebury Todd, of W. S. Gilbert’s comic poem “The Sensation Captain” (1868).

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Terry’s Theatre (p. 27)

Built in 1887 on the site of the Coal Hole tavern, the 800-seat theater was converted to a cinema in 1910. Hammond would have been fourteen some thirty-nine years before the 1924 publication of this novel if he is fifty-three now (p. 26), which works out to about 1885, before the theater was built. Either Hammond is misremembering his age at the time of the infatuation or is thinking of a different theater.

The Saturday Evening Post serial goes into more detail; once again, passages highlighted in yellow are omitted from the book text, and text omitted in Grand is in dark red:

In my case it was the passion I conceived at the age of fourteen for a lady who played in comic opera at Terry’s Theater. I used to sneak off and watch her from the gallery and write for her autograph and wish I could save her from red Indians. I sent her a shilling box of chocolates once. Heavens, how I loved that woman! There was none like her—none. Those were the days when lovely, free, unfettered goddesses roamed the earth—between eight-thirty and eleven at night—with their beautiful limbs emphasized by frank satin tights. It hardly gave a fellow a chance. I was bowled over like a shot rabbit the instant I saw her. Still, I’m glad that for one reason and another we were not able to marry. I suppose she would be about seventy-eight now. Much better to have her image tucked away in my heart, always as good as new. . . . Well, now tell me your romance. From the way you were speaking, I’m sure you’ve had one. Out with it! Some fatal, fascinating boy with a jammy face and a Lord Fauntleroy suit whom you met at a birthday party, eh?”

Flick smiled indulgently.

“It isn’t quite so long ago as that.”

“Oh, then there really was somebody? Come on, child, confide in me. I’m quivering with excitement. Very bad for me, too, at my age.”

“You’ll laugh at me.”

“Not I! You did not mock at my great love.”

Bob, the Sealyham terrier, had wandered up. Flick rolled him over on his back and pulled his ears absently for a moment without speaking.

none like her—none: see annotations to Sam the Sudden.

Sealyham terrier (p. 28)

A breed of dog developed in Victorian times by Capt. John Edwardes at Sealyham House in Wales for hunting small game; it has a white wiry coat and a strong jaw. Males grow to 12 inches at the shoulder and 20 pounds. Popular in the UK and US in the 1920s, the breed is in danger of dying out today. The Wikipedia article has photos of Sealyhams both in show trim and informally ungroomed.

Cooley Paradene is one of my best friends. (p. 28)

The magazine serials have this longer passage here:

Besides, Cooley Paradene is one of my best friends. We both collect old books, which gives us an excuse for writing to each other. Only man in the world I do write letters to. I’m always urging him to come here and pay me a visit. But how does he come into the story?

All the beautiful-opalescent-dream stuff. (p. 28)

Magazine serials insert “fairy-prince and” before “beautiful-opalescent-dream”.

about five years ago … at Harvard (p. 28)

We learn in chapter 2 §1, that Bill is twenty-six, so this accords well.

snapped up by now. (p. 29)

After this, magazine serials insert “Heroes don’t lie around loose for long.”

Chapter 2

Bill Undertakes a Mission

William Paradene West (p. 31)

Many of Wodehouse’s young heroes were christened William and called Bill; even some male romantic leads with other given names were called Bill. It seems likely that his longtime friend Bill Townend may have been a reason for Wodehouse’s preference for the moniker.

Among the Bills who end up getting the girl are the Rev. Cuthbert “Bill” Bailey (Service with a Smile), Bill Bannister (Doctor Sally), Bill Bates (pretending to be Alan Beverley in “The Man Upstairs”), Bill Belfry (Earl of Towcester/Rowcester in Ring for Jeeves/The Return of Jeeves), Bill Chalmers (Lord Dawlish in Uneasy Money), Thomas “Bill” Hardy (The Purloined Paperweight/Company for Henry), Bill Hollister (Something Fishy/The Butler Did It), Bill Lister (Full Moon, Galahad at Blandings), Bill Oakshott (Uncle Dynamite), and Bill West in the present novel. Also, Detective Henry Pifield Rice is dubbed “Bill the Bloodhound” in the story of the same name.

Exceptions to the rule: A woman, Wilhelmina Shannon (The Old Reliable) is called Bill. Bill Brewster (Indiscretions of Archie) is romantic, but gets neither of the two girls to whom he is attracted. William Bates of the golf stories is about the only romantic William who is not called Bill. Willoughby “Bill” Scrope (The Girl in Blue) is now a confirmed bachelor.

clad only in a suit of meshknit underwear (p. 31)

Wodehouse’s characters often prefer this fabric, though usually not as a sole garment. One widely advertised brand, “Porosknit” (see advertisement at right), was even mentioned in the lyric to “Bongo on the Congo” from Sitting Pretty (1924); see also Plum Lines, Winter 1997, page 16, in which David Landman first alerted Wodehouse readers to the topic.

King Merolchazzar calls for his mesh-knit underwear in “The Coming of Gowf”. Bertie Wooster wears mesh-knit underwear in “Jeeves Makes an Omelette”. In Summer Lightning Percy Pilbeam hides in a caravan because he had taken his damp trousers off to dry them, and didn’t want to be seen in knee-length mesh-knit underwear. Mr. Scarborough of the Cohen Bros. brings knee-length meshknit pants to Biff Christopher, who really wanted trousers, in Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions. The real-life producer Arch Selwyn is described as losing not only his shirt but his mesh-knit underwear at gambling in Bring On the Girls.

Wodehouse himself mentioned mesh-knit underwear as one of the kinds of gifts he would be glad to receive from grateful readers in “Attention All Patrons” (Punch, 13 July 1958).

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

rose to a demoniacal crescendo (p. 32)

See Heavy Weather.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

cushat dove (p. 33)

See Cocktail Time.

large quarterly allowance (p. 33)

Present-day readers may well be surprised at the number of Wodehouse’s young heroes who are supported by family money doled out periodically by older relatives. Bertie Wooster describes himself as having been “more or less dependent” upon his Uncle Willoughby six years earlier, at the time of “Jeeves Takes Charge” (1916). Since we hear no more about the uncle or Bertie’s allowance, we must presume that he has inherited control over his money, until, in the late story “Jeeves and the Greasy Bird” (1966), he pretends to be dependent on an allowance from his Aunt Dahlia in order to make a breach-of-promise suit against him seem less likely to be lucrative. Bingo Little, when we first meet him, is dependent on an allowance from his uncle Mortimer Little, later Lord Bittlesham. Bruce “Corky” Corcoran gets a small quarterly allowance from his uncle Alexander Worple in “Leave It to Jeeves” (1916). Psmith gets an allowance from his father in addition to his meager income from the bank in Psmith in the City (1908/1910), as did Wodehouse himself. Spennie, Lord Dreever in The Intrusions of Jimmy (1910), loses his allowance after two years at college, when his uncle cuts him off after losses at gambling. Freddie Threepwood’s allowance was stopped before we meet him in Something Fresh (1915). Rocky Todd’s aunt gives him an allowance, with conditions, in “The Aunt and the Sluggard” (1916). The Duke of Dunstable, before succeeding to the title, had “an allowance big enough to choke a horse” (A Pelican at Blandings, 1969); in his turn he is obliged to help support his nephew Archie Gilpin with an allowance (Service with a Smile, 1961). Some other recipients of allowances include Jimmy Crocker (Piccadilly Jim, 1917), Galahad Threepwood (Full Moon, 1947, and others), Stanwood Cobbold (Spring Fever, 1948), Freddie Widgeon (Ice in the Bedroom and many short stories including “The Masked Troubadour”), Lionel Green (Money in the Bank, 1942), Bicky Bickersteth (“Jeeves and the Hard Boiled Egg”), Mervyn Mulliner (“The Knightly Quest of Mervyn”), and Tubby Vanringham (Summer Moonshine).

the trees of Central Park across the road (p. 33)

It is clear that Bill West is enjoying his large quarterly allowance in part by renting a well-situated apartment. Then and now, living adjacent to Central Park is highly desirable and correspondingly expensive. Plum and Ethel Wodehouse rented an apartment at 375 Central Park West in 1915–16, and he used “C. P. West” as one of his many pseudonyms in articles for the US Vanity Fair magazine during that period.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

voice … of Conscience (p. 34)

Many of Wodehouse’s characters, from the school stories onward, are possessed of an active conscience. Actual reported speech from Conscience is rarer; Ann Moon’s conscience speaks to her several times in Big Money (1931) and Lord Emsworth hears the voice of Conscience in “The Crime Wave at Blandings” (1936). Beach interprets Millicent’s call as the voice of conscience in Summer Lightning (1929); Jeff Miller has talked things over with his conscience in Money in the Bank (1942). Bertie Wooster would have taken Edwin the Boy Scout’s exclamation to be the voice of Conscience in Joy in the Morning (1947) if he hadn’t also said “Coo!” Indirectly reported messages of the voice of conscience can be found in Uneasy Money (1916), Piccadilly Jim (1917), Leave It to Psmith (1923), “Tuppy Changes His Mind”/“The Ordeal of Young Tuppy” (1930), “Excelsior” (1948), Something Fishy (1957), and Do Butlers Burgle Banks? (1968), among others.

beasts of the field (p. 34)

A frequent phrase in the Bible and literature, so it is impossible to say precisely which inspired this one. In Biblia Wodehousiana Fr. Rob Bovendeaard considers Daniel 4:32, in which Nebuchadnezzar dwells with the beasts of the field and eats grass, as the most likely parallel.

Harvard (p. 34)

Other Harvard men in Wodehouse’s fiction include James Datchett in the US version of “Out of School” (1909), Bob the cracksman in “The Gem Collector” (1909); John Maude and Rupert Smith in US versions of The Prince and Betty, Ashe Marson in the US version of Something New (1915), George Bevan in A Damsel in Distress (1919), the Oldest Member in the US book version of “The Heel of Achilles” (Golf Without Tears, 1924), Cyril J. Davenport in the American magazine version of “Monkey Business” (1932). Fillmore Nicholas, in The Adventures of Sally (1921/22), had been expelled from Harvard.

[The Grand serial substitutes “college” for Harvard in both places on this page, although Flick’s earlier mention of Bill at Harvard is retained in the serial.]

you were in the football team (p. 34)

Both magazine serials read “you made the football team” here, a more American locution which seems likely to have been Wodehouse’s original usage.

Uncle Jasper (p. 35)

There are many Jaspers in Wodehouse, and not one of them is nice. Many are “bad baronets” in the tradition of W. S. Gilbert; see Leave It to Psmith for a list of these. The present Jasper is not evil, but hardly worth supporting, as we will see.

Diego Seguí notes:

The name Jasper seems to be somehow associated with villains in Victorian literature. Una McGovern in Dictionary of Literary Characters says that Jasper Milvain (a character from George Gissing’s 1891 New Grub Street) has a “stock villain’s name”. The most prominent baddie of this name, of course, is John Jasper from Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

exordium (p. 35)

A rare Latinate word, usually meaning the beginning part of any speech or document. Wodehouse seems to use it for a speech of chastisement (as here) or instruction (Money in the Bank, ch. 26), even after the lesson is finished; in Big Money, ch. 9, “Lady Vera began to deliver the exordium which she had roughed out in the train.” I wonder if Wodehouse was confusing this word with exhortation.

excrescence (p. 35)

From Latin roots meaning “growing outward”; most frequently used anatomically for an abnormal protrusion or swelling such as a wart or tumor. Figuratively, a useless or undesirable person or thing.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

old Adam (p. 36)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

collecting old books (p. 36)

Wodehouse’s frequent theatrical collaborator, the composer Jerome Kern, was an avid collector of rare books; he added a new room to his Bronxville home, twenty-four feet square, lined with bookshelves, about 1920, for his library of English and American first editions and manuscripts. See this article for more. It seems likely that Kern’s bibliophilia influenced the same mania in the character of Cooley Paradene.

cold shower (p. 37)

See A Damsel in Distress.

HEART-BALM (p. 37)

Though the idea here is clearly that of money awarded to soothe the emotional pain of a divorce, the term “heart balm” was more widely used in the awarding of damages in a breach-of-promise-of-marriage lawsuit, in which one party (usually the woman) could sue for financial damages if the other party (usually the man) had promised to marry but had broken the engagement. In response to widespread abuse of this sort of case, most US states had abolished “heart-balm laws” by the end of the 1930s. The UK did so in the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1970.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

super-film (p. 38)

See Leave It to Psmith.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

cuts three thousand feet (p. 38)

A bit of explanation will show this to be an exaggeration. In the early days of silent film, cameras and projectors were hand-cranked rather than motorized; from a nominal rate of sixteen frames per second set by Edison, speeds gradually advanced in order to give smoother motion without flicker, so that by the mid-1920s frame rates were typically in the range from 22 to 24 per second, close to the 24 adopted as the standard for sound film later in the decade. Still, it was typical during the silent era to describe the length of a movie in feet rather than minutes. As frame rates increased, the running time of a standard 1000′ reel decreased from about fifteen to about eleven minutes, so in 1924 three thousand feet would be on the order of thirty-five minutes, or about half the length of a standard feature, or roughly one-third of a super-film.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

parasangs (p. 38)

See Thank You, Jeeves.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Such a frown as St. Anthony might have permitted himself (p. 39)

Wodehouse doesn’t explicitly specify which St. Anthony he means, but we can take this together with his other references:

“I have it on the most excellent authority that you are entangled with a chorus-girl. How about it?”

Hugo reeled. But then St. Anthony himself would have reeled if a charge like that had suddenly been hurled at him.

Summer Lightning, ch. 1 (1929)

“What great good fortune that you should arriving on this particular day, my Packy, and that we should so happily have met. We will whoop it up.”

St. Anthony might have equalled Packy’s stare, but only on one of his best days.

Hot Water, ch. 3 (1932)

…on [Pongo’s] face a close observer would have noted at the moment an austere, wary look, such as might have appeared on that of St. Anthony just before the temptations began. He had a strong suspicion that now that they were alone together, it was going to be necessary for him to be very firm with this uncle of his and to maintain an iron front against his insidious wiles.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 2 (1948)

“My husband wouldn’t have the nerve to cheat on me if you brought him all the girls in the Christmas number of Playboy asleep on a chair.”

This was a disappointment to Chimp, for he knew that he was at his best when obtaining the necessary evidence, but Grayce continued to look so rich that he crushed down his natural chagrin and inquired why, if Mr. Llewellyn was such a modern St. Anthony, she wanted an eye kept on him and his every move watched.

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 3 (1972)

The common theme of avoiding temptation pins the identification on St. Anthony of Egypt, also known as Anthony the Great and Anthony Abbot (c. 251–356), an early Christian hermit, often taken to be the founder of the monastic tradition in Christianity. His biography, written by the near-contemporary St. Athanasius, depicts a series of temptations by the Devil which Anthony resisted by the power of faith and prayer. More at Britannica.com. The temptations have been the inspiration for paintings by Hieronymus Bosch and many others, as well as a novel by Gustave Flaubert.

[Thanks to Diego Seguí and Ian Michaud for suggestions.]

Never-Say-Die (p. 39)

Bertie Wooster notes that Worcester Sauce is an ingredient in Jeeves’s hangover cure in “The Delayed Exit of Claude and Eustace”; Jeeves mentions it generically among the ingredients in the magazine version of an early story:

It is the dark meat-sauce that gives it its color. The raw egg makes it nutritious. The red pepper gives it its bite.

“Jeeves Takes Charge” (1916)

In this story as collected in Carry On, Jeeves!, the proprietary name Worcester Sauce is used.

Karen Shotting identified spirits of ammonia as another likely ingredient in an article in Plum Lines, Summer 2018, page 13.

All female voices sound very much alike over the telephone (p. 40)

See A Damsel in Distress.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

cut the pages of a detective novel (p. 41)

In traditional hardcover bookbinding, a large printer’s sheet of paper containing several pages is folded once (folio), twice (quarto), thrice (octavo), etc. to make a signature, whose “spine” edge is sewn together; the signatures are then sewn and/or glued together along the spine edge in binding the book. Often the upper and lower edges of the pages would be mechanically trimmed in the binding process, but in smaller book sizes (octavo and beyond) some of the right-hand edges would still be connected as they were in the signature folding.

Some buyers preferred uncut pages as a guarantee that a book was new and unread, so it was worth it to them to carry a paper-knife (a not-very-sharp blade something like a letter opener) to separate the pages. Here Judson has used the stiff cardboard backing of a formal portrait photograph for the same purpose.

See also “Wilton’s Holiday” for another mention of using a photograph as a paper-knife.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

the nation’s songs (so much more admirable than its laws) (p. 42)

The sentiment “Let me write the songs of a nation, and I don’t care who writes its laws” is frequently attributed to Andrew Fletcher (1655–1716), but the original quotation, according to Bartlett, is:

If a man were permitted to make all the ballads, he need not care who should make the laws of a nation.

Conversation Concerning a Right Regulation of Governments for the Common Good of Mankind (1704)

Many will think of the verse of the Irving Berlin song “Let Me Sing and I’m Happy”:

What care I who makes the laws of a nation;

Let those who will take care of its rights and wrongs.

What care I who cares

For the world’s affairs

As long as I can sing its popular songs.

Though this song is clearly influenced by Fletcher as well, it was not Wodehouse’s source; it was probably written in 1927 and registered for copyright as an unpublished work in 1928; Al Jolson introduced it in the 1930 film Mammy.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

look for the silver lining (p. 42)

Title of a 1919 song, lyrics by B. G. DeSylva, music by Jerome Kern, originally written for the unsuccessful musical Zip Goes a Million and reused in Sally (1920), a show to which Wodehouse contributed other lyrics, causing some confusion about authorship, especially since the later edition of the sheet music issued with a cover featuring the film version of Sally credits Wodehouse as sole lyricist.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

The lyrics of the song’s chorus:

Look for the silver lining,

When e’er a cloud appears in the blue,

Remember somewhere the sun is shining,

And so the right thing to do is make it shine for you.

A heart full of joy and gladness

Will always banish sadness and strife,

So always look for the silver lining,

And try to find the sunny side of life.

Diego Seguí contributes these further notes:

The source of the proverb “to every cloud there is a silver lining” can be traced to Milton’s Comus (1634), lines 221ff:

Was I deceived, or did a sable cloud

Turn forth her silver lining on the night?

I did not err: there does a sable cloud

Turn forth her silver lining on the night,

And casts a gleam over this tufted grove.

The saying became popular in the second half of the 19th century. Apparently it started with the 1840 novel Marian, or a Young Maid’s Fortunes by A. M. Hall, which quoted Milton’s lines on the title page, and in ch. II attributes the saying to the character Katty:

Katty was so firmly resolved that no stigma should attach itself to her ward [Marian, the heroine], that she acted with more precipitation than prudence. The probability of her darling wanting the necessaries of life would have crushed a less hopeful spirit; but her own beautiful aphorism, that “There is a silver lining to every cloud,” supported her under privations which no mere worldly wisdom could have struggled through.

After this it is often quoted or used in titles, e.g.:

1850 “There’s a Silver Lining to Every Cloud”, poem [by Eliza Cook]

1853 The Cloud with the Silver Lining, novel [by Mrs. H. S. Mackarness]

1859 Cheerful Heart, or, “A Silver Lining to Every Cloud”, novel [anonymous]

c. 1863 “There’s a Silver Lining to Every Cloud”, ballad by Claribel [Ch. A. Barnard]

Wodehouse first used it in “Lines by a Host” (1904):

However, by idle repining

There’s nought to be gained, so I hold;

And the cloud has its own silver lining—

Some day this young man will grow old!

seek the Blue Bird (p. 42)

Maurice Maeterlinck’s 1908 play L’Oiseau bleu is the source of the concept of the Blue Bird as a symbol of happiness. Hundreds of songs mention this, but so far a search has not identified one from before this book was written.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

put all our troubles in a great big box and sit on the lid and grin (p. 42)

This is a slight misquotation of one of Wodehouse’s own lyrics, from the Bolton–Kern–Wodehouse musical Sitting Pretty, which had opened in April 1924. The published sheet music to “Worries” reads:

Crying never yet got anybody anywhere,

So just stick out your chin and

Shove all your worries in a great big box

And sit on the lid and grin!

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Old Man Trouble (p. 42)

This is another case where the song Wodehouse knew in 1924 was not the one we think of today. The Gershwins wrote “I Got Rhythm” originally for Treasure Girl in 1928, in a slow setting, and when that show closed after only 68 performances, it was reworked as an up-tempo number for Girl Crazy (1930), in which Ethel Merman made it a hit and herself a star.

The Fats Domino number “Old Man Trouble” by Jerry Smith is even more recent, from 1964. The combination of these two widely popular numbers makes searching for an early-1920s song with this phrase difficult.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Diego Seguí finds two possibilities:

• “Old Man Trouble” (part song for mixed voices, words anon., music by Daniel Protheroe, copyrighted 1916)

• “Old Man Trouble” (for male voices, words from Washington Star, music by Stanley F. Widener, copyright 1918)

The latter goes:

Old Man Trouble has an irritatin’ way

Of makin’ conversation, when he hasn’t much to say;

He isn’t entertainin’ an’ he isn’t very wise,

An’ he simply hollers louder when he wants to emphasize.

Old Man Trouble never helps the work along,

He wants the world to stop an’ hear his wailin’ loud an’ long;

There’s no use interferin’ while he’s usin’ up his breath.

We hope he’ll keep on talkin’ till he talks hisself to death.

registering devotion, sympathy, and willingness (p. 43)

See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Lucky Pig (p. 44)

According to one of the Oxford museums, pigs of gold, silver, or enameled porcelain were popular lucky charms in the era.

Diego reminds us that another lost lucky pig shows up in ch. 10 of Ice in the Bedroom (1961):

“I can wait. Say, listen. What I came about was that lucky pig of mine.”

“That . . . I beg your pardon?”

“Little silver ninctobinkus I wear on my bracelet. I’ve lost it.”

leaving the party any moment now (p. 44)

The Saturday Evening Post serial adds “and going home” to this sentence. The Grand serial omits this passage.

one of those peculiar Beasts in the Book of Revelations (p. 44)

Once again, Biblia Wodehousiana gives commentary. The formal title in the KJV is The Revelation of St. John the Divine; Wodehouse follows the popular error of making Revelations plural.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

oldest inhabitant (p. 44)

See The Inimitable Jeeves.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

family prayers (p. 46)

Wodehouse’s young characters often consider this practice an imposition on their freedom. Other homes with family prayers are mentioned in “Disentangling Old Percy” (1912), Piccadilly Jim, ch. 1 (1917), “The Début of Battling Billson” (1923), and in “Fate” (1931; in Young Men in Spats, 1936). US editions of Thank You, Jeeves also have a mention in a passage cut from UK editions.

There is a tide in the affairs of men which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune (p. 46)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse for more citations of this quotation from Brutus in Julius Caesar.

Yale Bowl (p. 46)

This football stadium in New Haven, Connecticut, was built in 1913–14, the first bowl-shaped stadium in the USA; its design and name influenced many other stadia including the Rose Bowl. Original seating capacity was 70,896.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Westbury, Long Island (p. 48)

A village in Nassau County, New York, about 18 miles east of Manhattan along the Long Island Rail Road, and some seven miles east of Great Neck, where Wodehouse lived part of the time between 1918 and 1922. In the late 19th century what had been mostly an agricultural village was transformed by new wealthy residents who built “country” mansions which were still convenient to the city via rail; the upper-class section of town came to be called Old Westbury. In The Old Reliable (1951), Wilhelmina “Bill” Shannon once wrote a romance whose hero “was one of the huntin’, ridin’ and shootin’ set of Old Westbury, Long Island.” In Company for Henry (1967) the butler Ferris recalls disturbing goings-on at the Waddingtons’ country residence at Old Westbury.

Atlantic Monthly (p. 48)

Founded in 1857 in Boston as a magazine of literature, art, and politics, it has retained a prominent role in USA periodical publications to the present day, although in recent years it has dropped the Monthly from its title, changed to a ten-issues-per-year schedule, and moved to Washington, D.C.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Quarterly Review (p. 48)

One of Britain’s most influential periodicals, founded in 1809 and published by John Murray. It concentrated on literary and political issues, generally with a moderate political philosophy. Its final issue came out in 1967.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

Mercure de France (p. 48)

Many French periodicals have appeared under the label Mercure since the 17th century; the present journal was founded in 1890 and became bimonthly in 1905.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

masses of laburnum (p. 48)

Several species and hybrids of laburnum, a decorative tree of the pea family, are commonly used in ornamental gardens; in spring they feature long clusters of golden-yellow flowers.

yestreen (p. 49)

A Scottish dialect variation of “yesterday evening” relatively much rarer in usage after 1910 or so. Spelled yestere’en in SEP serial; omitted in Grand.

Diego Seguí reminds us that Jimmy Crocker used it in Piccadilly Jim, chapter 4:

“Well, it’s a funny thing, but I can’t get rid of the impression that at some point in my researches into the night life of London yestreen I fell upon some person to whom I had never been introduced and committed mayhem upon his person.”

and that Bertie Wooster is fond of the word:

That matter we were in conference about yestereen.

“The Inferiority Complex of Old Sippy” (1926)

Why on earth didn’t you stop Miss Stoker from swimming ashore yestreen?

Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 11 (1934)

Waking next morning to another day and thumbing the bell for the cup of tea, I found myself, though still viewing the future with concern, considerably less down among the wines and spirits than I had been yestreen.

Joy in the Morning, ch. 5 (1946)

“You have not forgotten our telephone conversation of yestreen, Jeeves?”

How Right You Are, Jeeves, ch. 11 (1960)

Oh, love! Oh, fire! (p. 49)

Probably quoted from Tennyson’s “Fatima” (1833):

O Love, O fire! once he drew

With one long kiss my whole soul thro’

My lips, as sunlight drinketh dew.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

pale reptilian eye (p. 50)

An uncommon adjective in Wodehouse:

She had never yet been frightened of any man, but there was something reptilian about this fat, yellow-haired individual which disquieted her, much as cockroaches had done in her childhood.

Jill Mariner, gazing at Mr. Goble in The Little Warrior/Jill the Reckless (1920/21)

It was not Hugo who was Sue’s companion, but a reptilian-looking squirt with narrow eyes and his hair done in ridges.

Ronnie Fish’s view of Percy Pilbeam in Summer Lightning, ch. 4 §3 (1929)

old crumb (p. 50)

The OED calls crumb originally US slang for “an objectionable, worthless, or insignificant person” with citations only as far back as 1918. Another citation is Wodehouse’s use of it in Very Good, Jeeves referring to Sir Roderick Glossop, first published as the short story “Jeeves and the Yule-Tide Spirit” (1927):

…Jeeves had been aware all along that this old crumb would be the occupant of the bed which I was proposing to prod with darning needles…

See also Uncle Dynamite, in which Otis Painter thinks this of Sir Aylmer Bostock.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

“Good God! … Is this Old Home Week?” (p. 51)

The SEP serial substitutes “Great heavens!” to soften Uncle Jasper’s oath. Old Home Week is a tradition originating in New England in the late nineteenth century, a festival celebrated in towns and villages either annually or every few years, in which former residents who grew up in the municipality are invited to return to their old home town during the festivities.

picking at the leather of an armchair with the nib of a pen (p. 51)

Reminiscent of Mary, Mrs. Charlie Ferris, in “At Geisenheimer’s” (1915):

She dug away at the red plush with the hatpin, picking out little bits and dropping them over the edge.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

“when a man has passed sixty he’s simply waiting for the end” (p. 51)

Wodehouse was not yet forty-three when he wrote this, but of course this is not his own opinion but that of a rather fluffy-minded character. In “Company for Gertrude” (1928) the title character at twenty-three feels the hopelessness of life, longing for “the ineffable peace of the grave” and mourning that it would be long in coming since “all our family live to sixty.” So this may just be a way of indicating the span of life as seen by a young person. Fortunately for us, Wodehouse would stay productive for another half-century, continuing to write into his nineties.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

“Save us a lot of money on the inheritance-tax” (p. 51)

At this time, there was no federal gift tax in US law; it was instituted in 1932 as a means of at least partly removing this incentive to distribute money to relatives during the donor’s lifetime. Since the gift tax rate was initially lower than the estate tax rate, there was still some benefit to making settlements, but at least the loophole Uncle Jasper envisions here was partly closed.

[The Grand serial omits this passage.]

The little man in the doorway (p. 53)

The SEP serial omits “little” here.

“thought it so sweet of you to invite us” (p. 53)

The SEP serial has “so cute and sweet of you” here; the Grand serial omits a large chunk of dialogue at this point.

Sensation. (p. 54)

See Summer Lightning.

wild surmise (p. 55)

“Gee whistikers” (p. 55)

An apparently unique variant of “Gee whillikers”; most slang references treat this as a modified oath, with Gee for Jesus and the second part used as an intensive.

prunes (p. 55)

Slang dictionaries seem only to cite negative senses of “prune” for a disliked, foolish, prissy, or disagreeable person, frequently an older one; this seems to be Horace’s intent here. But see Right Ho, Jeeves for the variant form “young prune” with quite a different connotation.

frock coat (p. 55)

A man’s suit jacket which extended to a knee-length skirt all around its lower edge, originating as ordinary informal daytime wear in Victorian times, but gradually becoming considered more formal (especially in its double-breasted variety) and more conservative than newer styles of tailcoat with the front of the skirt cut away. By the time of this book, the frock coat was most often seen in political and diplomatic circles, so Professor Appleby’s choice of it was probably intentionally designed to give him an authoritative air. Edward VIII (later the Duke of Windsor) abolished the frock coat as official British court dress in 1936.

minor prophet (p. 55)

See Biblia Wodehousiana for Fr. Rob’s commentary.

[The Grand serial omits the first reference to “minor prophet”; this makes later ones a bit confusing.]

joyous gathering (p. 56)

A misprint in the US first edition (Doran, 1925). The SEP magazine serial and UK first edition read “joyless” here, obviously the correct version to match the context; the Grand serial cuts the last half of the sentence.

“Do I have to kiss them all?” he asked. (p. 56)

Both magazine serials add “apprehensively” after “he asked” here.

Eugenics (p. 56)

Capitalized in books, but lower-cased in both magazine serials, the term was coined in 1883 by Francis Galton to describe approaches to improving the genetic quality of the human population. It became associated with both scientists and pseudo-scientists, with political and social movements across the spectrum, and was widely discussed and promoted in the early decades of the 20th century. In retrospect, especially after the racial purity policies of Nazi Germany became known, many earlier supporters of eugenics have been viewed as racist, white supremacist, xenophobic, and otherwise dangerous to human liberty and equality. It is interesting to see Wodehouse viewing proponents of eugenics with suspicion and disfavor even as early as 1914’s The White Hope (later in book form as The Coming of Bill, 1920), in which Lora Delane Porter is portrayed as an interfering crank, and this book, in which Professor Appleby pretends to be a eugenicist for criminal ends. Even Bertie Wooster is suspicious of Aunt Agatha’s concern for “the future of the race” in “Scoring Off Jeeves” (1922, collected in The Inimitable Jeeves, 1923, as chapters 5–6).

Ian Michaud reminds us that this book has some similarities to the plot of the musical comedy Sitting Pretty (Bolton–Wodehouse–Kern, 1924), in which William Pennington, a grumpy old man not nearly as nice as Uncle Cooley Paradene, is a passionate believer in eugenics. He set the plot in motion by disinheriting his worthless, sponging relatives, and setting out to create a new family by adopting a son named Horace (much older than the boy in the book; played on stage by 25-year-old Dwight Frye, later famous in horror movies) and a daughter from the neighbouring orphan asylum, with the plan to breed them to produce “fewer but better Penningtons.” His plans were upset by the fact that his nephew Bill and the new daughter fall in love, while Horace, besides being in love with the new daughter’s twin sister, was working the inside stand with his Uncle Jo in a plot to loot the Pennington estate of its valuables.

Bernard Shaw … new race (p. 56–57)

Even in early works like Cashel Byron’s Profession, Shaw mentions eugenics in terms of choosing a mate with complementary strengths to balance weaknesses. A 1914 critical study noted that “he degrades a character in order to convince us how very necessary it is to breed a new race and not waste time tinkering with such inferior stuff.”

But Shaw’s vision had a very ugly side; as early as 1910 he said “We should find ourselves committed to killing a great many people whom we now leave living... A part of eugenic politics would finally land us in an extensive use of the lethal chamber. A great many people would have to be put out of existence simply because it wastes other people’s time to look after them.” His later statements on the subject are too repugnant and specific to quote here.

to fall squashily to the floor (p. 57)

The SEP serial omits the last three words.

as popular as a cold welsh rabbit (p. 58)

sanguine countenance (p. 59)

In the classical theory of temperaments, those whose personality is ruled more by the blood than by other fluids such as phlegm and bile are called “sanguine”; they tend to be cheerful, optimistic, and outgoing. Wodehouse seems not to be using the term in this manner for Mr. Paradene; here it refers to having a ruddy complexion, as in the “red clean-shaven face” of his first description (p. 52).

ten dollars a week (p. 59)

Roughly equivalent in buying power to $150 in 2019, according to this website.

perfect peace (p. 60)

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

a tale of desert love (p. 60)

We learn a few pages later that this is Sand and Passion, a title not found in libraries today according to worldcat.org, so presumed fictitious. The popularity of the desert romance genre was sparked by the success of E. M. Hull’s 1919 novel The Sheik and its 1921 film version starring Rudolph Valentino.

Diego points out that a few months earlier than the appearance of this book in serial form, in “Rodney Fails to Qualify” (1924), Jane Packard is reading The Love That Scorches by Luella Periton Phipps, “all about the desert and people riding on camels and a wonderful Arab chief with stern yet tender eyes and a girl called Angela and oases and dates and mirages and all like that.”

dust-coat (p. 60)

A long light overcoat worn to protect clothing from being dirtied while driving or riding in an open automobile or carriage. See “The Deserter” for an illustration from a 1905 school story. Billie Dore wears one for motoring in chapter 8 of A Damsel in Distress.

“Hallo,” said this young man, spitting out gravel. (p. 60)

Both magazine serials have “Hullo” here, and after this sentence add the additional speech “How’s everybody?”

coming up the drive at a pretty good lick (p. 61)

The OED calls the sense of lick as “a spurt at racing, a short brisk spin” as colloquial and as originally American, also in Australian and New Zealand usage. This seems to be the first usage in Wodehouse in this sense; earlier it has the more common meaning of “defeat” most often, as well as for a literal application of the tongue and in “a lick of paint.”

fairway (p. 61)

Judson uses golfing jargon here, seeing the drive ahead as part of the course; see A Glossary of Golf Terminology.

“Good God!” said Judson. (p. 61)

The SEP serial substitutes “Huh!” for the oath here and after the mention of the Fifth Avenue Silks on p. 63, and omits it entirely on p. 62, after Roberts disclaims acquaintance with Town Gossip.

Broadway Badinage … Town Gossip (p. 62)

Apparently fictional periodicals. The four-line exchange with Roberts beginning with the first of these is omitted in the Grand serial.

AK points out that the titles of these may have been influenced by real-life scandal sheets Broadway Brevities and Town Topics, though these were scurrilous rags that made a lucrative sideline in blackmail, and there is no indication that Judson felt anything but pride at being mentioned in the ones he names.

kindly physician … healing fluid (p. 62)

Roberts seems to agree with Bertie Wooster and other Wodehouse characters who look upon alcoholic beverages as restorative or as a bracer. Judson will make similar arguments for the health-giving properties of alcohol later in the book.

[The Grand serial omits the sentence referring to “kindly physician.”]

“Mix it pretty strong, will you?” (p. 62)

The SEP serial substitutes “Fix” here.

as a hen does of tooth-powder (p. 63)

The expression scarce as hen’s teeth is proverbial, but Wodehouse tweaks the cliché by mentioning a powdered dentifrice instead.

the Sunday magazine section of the American (p. 63)

Somewhat unusually, Wodehouse refers to a real newspaper, the New York American, published by William Randolph Hearst from 1895 to 1937, when it merged with his New York Journal to become the Journal-American. It had been founded in 1882 by Albert Pulitzer as the New York Morning Journal. The Sunday magazine section was typically a 16-page insert, printed in rotogravure for better reproduction of photographs and illustrations, beginning in 1896. A web page of illustrations from the American Weekly (archived at the Wayback Machine). The SEP serial avoids naming a specific publication by substituting “three Sunday magazine sections” here.

[The Grand serial omits the passage.]

“Because if there is I’m sunk.” (p. 66)

Both magazine serials read “Because if there is I’m in very Hollandaise” (“hollandaise” in SEP). Hollandaise is a sauce made by whisking egg yolks and lemon juice together, cooking lightly, then stirring in butter until the sauce thickens; the sauce is then seasoned with salt and usually some kind of pepper or paprika and kept warm until ready to serve. Other than the possibly mistaken reference to “ravioli hollandaise” in chapter 16 of The Adventures of Sally (chapter 12 in the US magazine serial) this seems the only mention of the sauce in Wodehouse. Of course this is a clever variant on “in the soup” (see The Inimitable Jeeves); one wonders why the book editors decided to substitute the very ordinary “sunk” here.

a particularly unspiritual wart-hog (p. 66)

The African wild pig of this name (genus Phacochœrus) makes a few appearances in Wodehouse, and not one is complimentary:

“But this girl is probably one solid mass of brain. She will look on me as an uneducated wart hog.”

Chester Meredith, speaking of Felicia Blakeney in “Chester Forgets Himself” (1923)

“Bertie, you have about as much imagination as a wart hog, but surely even you can picture to yourself what Jimmy Bowles and Tuppy Rogers, to name only two, will say when they see me referred to in print as ‘half god, half prattling, mischievous child.’ ”

Bingo Little in “Clustering Round Young Bingo” (1925)

And when, as happened a little farther on in the scene, Monty had called his former employer a fat, double-crossing wart-hog, the latter had terminated the interview by walking away with his hands under his coat-tails.

Heavy Weather, ch. 15 (1933)

“I don’t mind informing you that in my opinion you are behaving like a hound, a skunk, a worm, a tick, and a wart hog.”

Chuffy Chuffnell speaking to Bertie Wooster in Thank You, Jeeves, ch. 13 (1934)

“I shall be very terse about Tuppy, giving it as my opinion that in all essentials he is more like a wart hog than an ex-member of a fine old English public school.”

Bertie Wooster speaking of Tuppy Glossop in Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 13 (1934)

“And do you know what he’s gone and done now, the old wart-hog?”

Reggie Tennyson speaking of J. G. Butterwick in The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 3 (1935)

“Uncouth young wart hog.”

Lord Ickenham speaking of Ricky Gilpin in Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 6

“The only thing that can make me feel better is to thrash that pie-faced young wart-hog Fittleworth within an inch of his life.”

Lord Worplesdon in Joy in the Morning, ch. 28 (1947)

Gally’s monocle came swinging round at Jerry like the eye of a fire-breathing dragon. His face was hard and set.

“You abysmal young wart-hog!”

Pigs Have Wings, ch. 4 §iii (1952)

I thought this showed a vindictive spirit in the old wart hog and one that I deplored, but I felt it would be injudicious to say so.

Bertie Wooster, referring to Sir Watkyn Bassett in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 18 (1963)

Take a wart hog, add a few slugs and some of those things you see under fIat stones, sprinkle liberally with pimples, and you will have something which, while of course less loathsome than Alexander Prosser, will give you the general idea.

Bingo Little to Mabel Murgatroyd in “The Word in Season” (as revised for A Few Quick Ones, 1960)

Slingsby (p. 68)

This somewhat unusual surname seems to have been a favorite with Wodehouse. First used by Jeremy Garnet in Love Among the Chickens (1906, 1909, and 1921 versions, but not in US magazine serial) as Tom Slingsby, a character who saves the peppery old father in Garnet’s short story “Hilda’s Hero.” The chauffeur at Blandings Castle in Something New/Something Fresh (1915) is named Slingsby. Wilfrid Slingsby is the unscrupulous manager in this book, Bill the Conqueror. Alexander Slingsby of Slingsby’s Superb Soups and his wife Beatrice appear in “Jeeves and the Spot of Art” (1929). Theodore Slingsby is the butler at Langley End in If I Were You (1931). Horatio Slingsby is the author of Strychnine in the Soup in the short story (1932) of the same title. Crispin Scrope places his racing bets with Slingsby’s in The Girl in Blue (1970).

Mark Hodson found a real Slingsby family at Scriven Park, near Knaresborough; see Cocktail Time. Diego notes that the Oxford Dictionary of Family Names shows the surname as deriving from the village of Slingsby in North Yorkshire.

“As solemn as a what-d’you-call-it!” (p. 71)

The most common completions seem to be “as solemn as a judge” (anonymous) and “solemn as an owl,” attributed to Goethe in this collection of similes along with several other possible comparisons. Wodehouse seems not to have used any form of this simile elsewhere.

Romano’s (p. 71)

See A Damsel in Distress.

the Savoy bar (p. 71)

In the Savoy Hotel.

“get this into your nut” (p. 71)

Wodehouse masterfully contrasts Appleby’s professorial demeanor in the earlier scene in Mr. Paradene’s library with his slangy word choices when alone with Horace. The colloquial “nut” for “head” is cited as far back as 1841 in the OED.

good and solid in this house (p. 71)

Both magazine serials read “joint” instead of “house” here, which must have been Wodehouse’s original intention. See Sam the Sudden for more on the word choice.

picking daisies (p. 71)

Idling away one’s time; not attending to business. Compare:

I turned to Aunt Agatha, whose demeanour was now rather like that of one who, picking daisies on the railway, has just caught the down-express in the small of the back.

Bertie Wooster, in “Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” (1922)

Another use is in Money for Nothing.

Joe the Dip (p. 71)

Dip is nineteenth-century American slang for a pickpocket, first cited in the OED from an 1859 dictionary of thieves’ jargon.

bone-headed (p. 72)

US slang, with citations dating from 1883 in the OED, describing an unintelligent, stupid, or thoughtless person, by analogy to “thick-skulled”: leaving little room for brains. The OED cites Wodehouse’s use of it in Something Fresh (1915; in US as Something New), and he used it in roughly a dozen stories. For unknown reasons the SEP serial of Bill the Conqueror substitutes “dumb” here, which hardly gives the same flavor.

hook, line and sinker (p. 73)

Completely; the analogy is to a fish who eagerly snaps at the angler’s bait and swallows not only the fish hook and part of the fishing line, but also the lead weight (sinker) attached to the end of the line. This sentence from Bill the Conqueror is one of the example quotations for the phrase in the OED, among citations from 1838 to 1945. Other uses in Wodehouse:

Mrs. Gedge, he stated with confidence, had swallowed his story, hook, line, and sinker.

Packy Franklyn in Hot Water, ch. 14 §1 (1932)

…it was scarcely half an hour later that Dolly, having been informed over the telephone by her second in command that Mr. Twist had swallowed the whole setup, hook, line and sinker, and might be expected at the tryst any minute now, made her way to Lord Uffenham’s pantry.

Money in the Bank, ch. 15 (1942)

Chapter 3

Flick Pays a Call

the manner in which Spring comes to England (p. 74)

In “The Tuppenny Millionaire” (1912), Wodehouse refers to those tourists on the French Riviera

who wished to avoid the rigours of the English spring.

proletariat (p. 74)

This term for the working or lower classes had been borrowed from French into English by 1847, even before the Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels was published in 1848 in German and in 1850 in English. Wodehouse used it at least as early as 1911:

Harold, the proud office-boy, lost his air of being on the point of lunching with a duke at the club and perspired like one of the proletariat.

Claridge’s (p. 75)

See Summer Lightning.

We grey-beards (p. 75)

As noted above, Wodehouse was not yet forty-three when writing this. SEP serial has “graybeards” here.

syncopated appearance (p. 75)

No earlier appearance of this pair of words has been collected in Google Books, and this sentence is the first-cited example in the OED for the figurative use of syncopated. The term is more common in music, denoting the placement of musical notes at spots in the measure where accents do not normally fall, giving a shifting or flickering effect to the rhythm, a technique common in ragtime and jazz. Here the water’s ripples bend light rays to give a similar flickering effect to the view of the fish.

lightning changes (p. 76)

A clever reversal by Wodehouse of figurative to literal use of this phrase! The reference is to the vaudeville performer who single-handedly portrays multiple characters, dashing behind a screen for an instant to alter costume, makeup, and/or wig and coming out as a different personality; he or she would be billed as a quick-change or “lightning change” artist, as described in the article linked here.

There was an exclamation of patient anguish on the other side of the window, such as Prometheus might have uttered when his torment became almost too hard to bear. (only first half sentence, p. 76)

Both book editions stop at “window”; Grand serial omits the paragraph entirely. Only SEP serial includes the mythological reference to the everlasting torment of the immortal Prometheus, chained to a rock forever, whose liver is eaten each day by an eagle, only to regrow each night for the next day’s attack, until Heracles kills the eagle and breaks the chains.

Diego Seguí finds more:

Wodehouse alludes to Prometheus’ punishment elsewhere (e.g. The Little Warrior, ch. 4 §3: “Prometheus, with the vultures tearing his liver”; Big Money, ch. 7 §1: “like Prometheus watching his vulture”; and possibly whenever he wrote about vultures gnawing at someone’s entrails; see annotations to Lord Emsworth and Others). As can be seen, he regularly associates Prometheus with a vulture, but the more respectable sources, like Aeschylus or Hesiod, coincide in speaking of an eagle (Greek aietós). One who did have his liver eaten by vultures (Greek gýps) was the giant Tityos, according to the Odyssey, book XI.

Fortnightly (p. 76)

The Fortnightly Review was an influential magazine, founded in London in 1865, and dedicated to “the unbiassed expression of many and various minds on topics of general interest in Politics, Literature, Philosophy, Science, and Art.” Wodehouse joked in “Journalistic Jottings” (1908) what might happen to its contents if it were acquired by C. Arthur Pearson, publisher of newspapers and magazines for the masses.

“Crawshaw and Francis Thompson” (p. 76)

Both book editions read as above; Grand serial omits the paragraph; SEP reads “Crashaw” here. Francis Thompson (1859–1907) was an English poet and mystic, best remembered for the poem “The Hound of Heaven.” Crashaw (as in SEP) refers to Richard Crashaw (c.1612–1649), an English metaphysical poet, an Anglican cleric who converted to Catholicism. Diego Seguí notes that poet and critic Coventry Patmore (1823–1896) compared “Mr. F. Thompson, a New Poet” to Crashaw in an 1894 article in, yes, the Fortnightly Review.

When I have leisure—which, may I say politely but firmly, at the moment I have not—I will give you some statistics… (p. 77)

Both magazine serials read as above. Both book versions omit the phrase set off by dashes.

putting up the spout (p. 79)

popping (p. 79)

British slang for pawning, cited by the OED as far back as 1731 (Henry Fielding); OED includes Bertie’s use of it talking to Aunt Dahlia in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (1954):

“Pawned it?” I said.

“Pawned it.”

“Hocked it, you mean? Popped it? Put it up the spout?”

Mario’s Restaurant (p. 80)

See Ukridge.

three-mile limit (p. 80)

At the time of writing, most nations claimed that their legal authority extended three nautical miles (5.6 km) beyond their shoreline; since 1982 the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea has been adopted by most nations to define territorial waters as 12 nautical miles (22 km) from shore. In 1924, Prohibition was in force in the USA (Eighteenth Amendment and Volstead Act, 1919–1933), so even a British ship’s bar would be closed until beyond the three-mile limit. (Liners registered under the American flag observed Prohibition no matter where they sailed.)

Aquitania (p. 80)

A real-life ocean liner of the British Cunard Line, launched 21 April 1913, in service 1914–1950, including service as a troop carrier in both world wars. Before being reconfigured in 1926, it carried 618 first class, 614 second class, and 2,004 third class passengers plus a crew of 972.

Bill, he had felt, was ever a kidder (p. 80)

The OED gives both British and American citations for “kidder” in the late nineteenth century and a 1900 one from George Ade’s Fables in Slang, which we know Wodehouse enjoyed and mined for colloquialisms. Wodehouse’s own first use, in “The Rough Stuff” (1920, collected in The Clicking of Cuthbert, 1922), is cited in the OED.

shades of the prison-house began to close about the growing boy (p. 80)

From Wordsworth, Intimations of Immortality; see The Inimitable Jeeves.

This, thought Bill, was encouraging; and he spurned the pavement of Piccadilly as buoyantly as one of Mr. Marlowe’s satyrs treading the antic hay (p. 81; only first part in book)

Both book editions and Grand serial finish the sentence after “encouraging.” The SEP serial alludes to Christopher Marlowe’s play Edward the Second, in which Gaveston declares:

And in the day, when he shall walk abroad,

Like sylvan nymphs my pages shall be clad;

My men, like satyrs grazing on the lawns,

Shall with their goat-feet dance an antic hay.

The antic hay was a rustic dance, also alluded to by Wodehouse in Money in the Bank, ch. 13 (1942), and in Pigs Have Wings, ch. 1 §3 (1952).

Things, he felt, were looking up (p. 81)

The song “Things Are Looking Up” may come to mind, but it had not yet been written by George and Ira Gershwin when this book was written; it was part of the score of the 1937 film of A Damsel in Distress. It is pure speculation, but tempting to believe that Ira’s lyric for this Wodehousean film may have been influenced by this sentence, also used in Summer Lightning, ch. 7.3 (1929) and If I Were You (1931); other lyrics in the film are explicitly based on Wodehouse phrases, especially the song “Stiff Upper Lip.” The usage of the phrase “looking up” for an increase in value originated in nineteenth-century financial circles, as for stock prices, and then generalized to any favorable expectation.

This new arrival was made of sterner stuff altogether (p. 82)

See Shakespeare Quotations and Allusions in Wodehouse.

bounder (p. 83)

British colloquial term for a cad, one whose manners are outside the norms of society; originally cited in an 1889 slang dictionary. Both magazine serials use the American term “four-flusher” instead here, defined as “a pretender, braggart, humbug” in the OED. The root is from the game of poker, in which a four-flush is a worthless hand, a failed attempt at getting five cards of a single suit.

Battersea. Marmont Mansions. (p. 85)

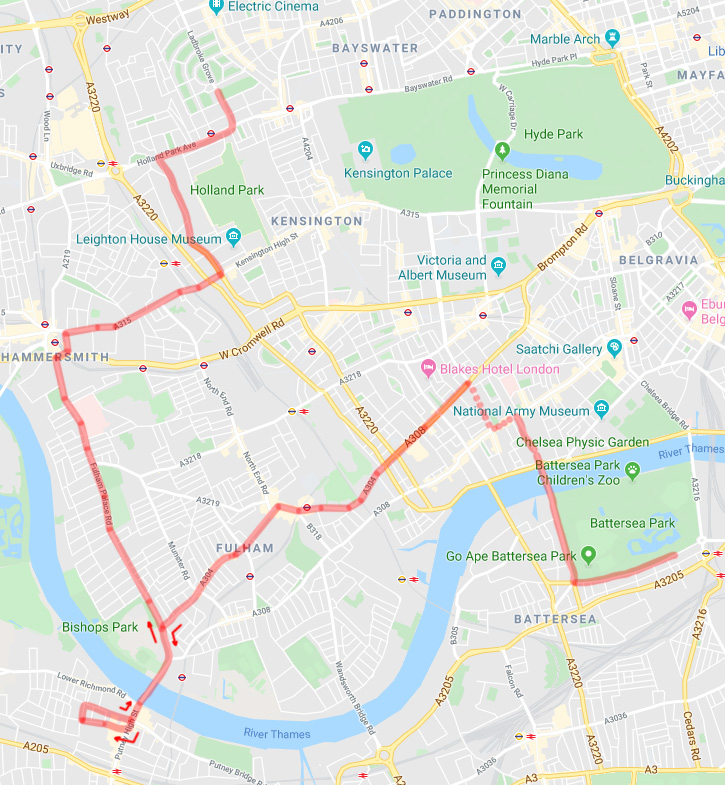

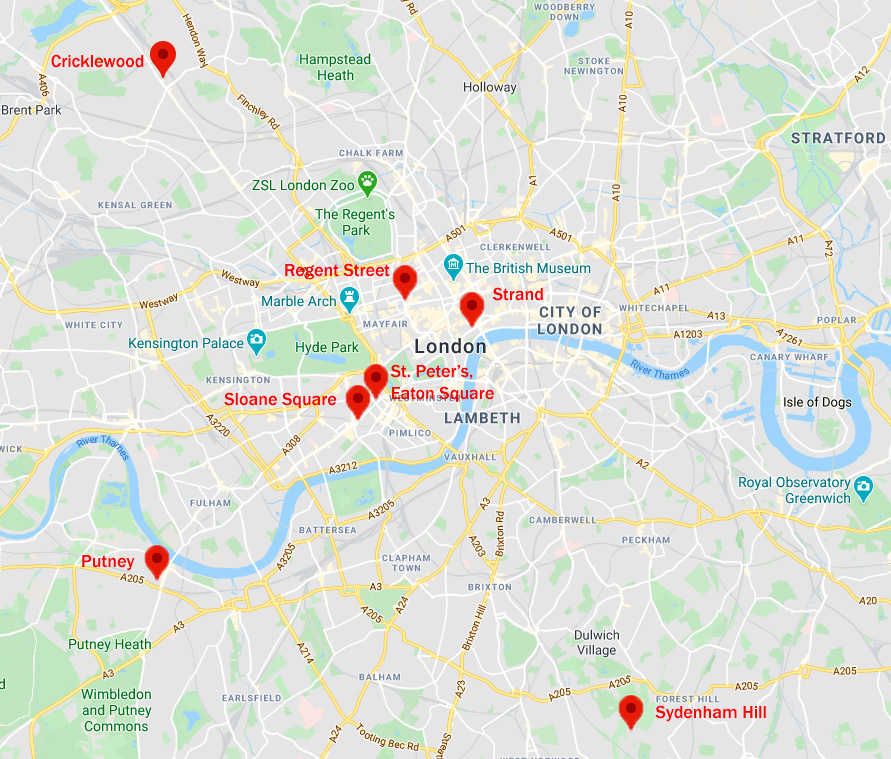

The Battersea area of London is on the less-fashionable south bank of the Thames, connected to Kensington and Chelsea by the Albert Bridge, the Battersea Bridge, and the Chelsea Bridge. Its most striking current landmark, a now-disused power station, was built in 1933, and so was not present when this book was written. One of its most pleasant aspects is Battersea Park, on the south bank of the Thames between Albert Bridge Road and Chelsea Bridge Road/Queenstown Road; its southern boundary is Prince of Wales Drive. Blocks of mansion flats were built beginning in the 1890s on the south side of the Drive, thus overlooking the park. In one of these, Prince of Wales Mansions, Wodehouse himself lived for a time in 1913 at Number 94; in the 1952 novel Pigs Have Wings Jerry Vail lives at Number 23 in Prince of Wales Mansions; in the 1961 novel [The] Ice in the Bedroom Leila Yorke recalls living in a flat there early in her married life. Since in real life none of the mansion blocks is called Marmont, and Wodehouse had a practice of using sites he knew in his fiction, it is easy to assume, as N.T.P. Murphy did in In Search of Blandings, that Marmont Mansions is a pseudonym for the real-life Prince of Wales Mansions. [Thanks to IM for reminding us of the parallel location.]

the ungirt loin (p. 86)

Figuratively, casual or incomplete dress; Jeremy Garnet looks forward to the same in original editions of Love Among the Chickens (1906–09) as he contemplates life in a rural retreat. See Biblia Wodehousiana for Fr. Rob’s take on this.

the shop in the Burlington Arcade (p. 87)

A covered passage in London, connecting Piccadilly with Burlington Gardens, lined with small luxury shops. Built in 1818 by George Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington, adjacent to his Burlington House; it is an early example of the shopping galleries of Europe and a precursor of today’s shopping malls. Both magazine serials read “the store on Forty-Second Street” here, suggesting a New York origin for the socks.