Heavy Weather

by

P. G. Wodehouse

Literary and Cultural References

This is part of an ongoing effort by the members of the Blandings Yahoo! Group to document references, allusions, quotations, etc., in the works of P. G. Wodehouse.

Heavy Weather has been annotated by Deepthi Sigireddi and Neil Midkiff, with contributions from Diego Seguí, John Dawson, and others as credited. It is a direct sequel to the 1929 novel Summer Lightning (US title: Fish Preferred), and in story time it takes place some ten days later, or perhaps in the next month (see ten days and August below).

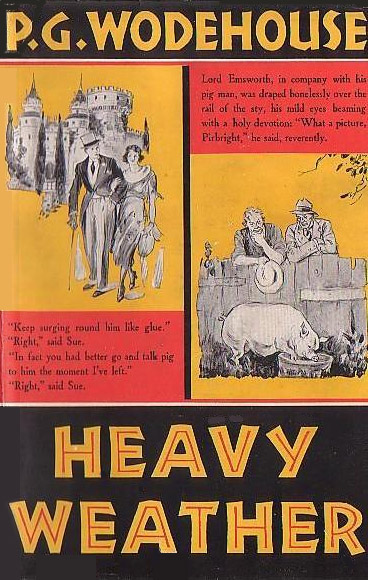

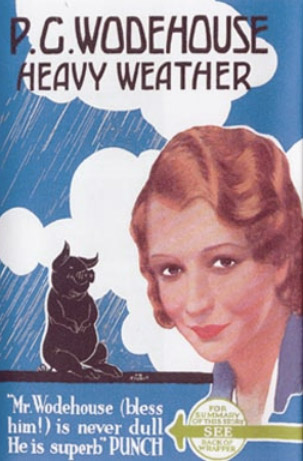

Heavy Weather was first published on July 28, 1933, by Little, Brown, and Company, Boston [left], and on August 10, 1933, by Herbert Jenkins, London [right]. It was serialized in

the Saturday Evening Post prior to book publication; see this page for details of serial appearances.

Heavy Weather was first published on July 28, 1933, by Little, Brown, and Company, Boston [left], and on August 10, 1933, by Herbert Jenkins, London [right]. It was serialized in

the Saturday Evening Post prior to book publication; see this page for details of serial appearances.

These annotations and their page numbers relate to the Penguin paperback edition (1966 plates, “set in Monotype Times” and reprinted many times), in which the text covers pp. 5–249.

|

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 |

Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 |

Chapter 1

Fleet Street (ch.1, p.5)

A major street in London. It became known for printing and publishing in the 16th century. Many newspapers had their offices there until the 1980s.

Mammoth Publishing Company (ch.1, p.5)

Norman Murphy traces the original of this to Amalgamated Press, owned by Lord Northcliffe. See Bill the Conqueror for more.

Lord Tilbury (ch.1, p.5)

This is Lord Tilbury’s fourth appearance in the canon. We first meet Lord Tilbury as Sir George Pyke in Bill the Conqueror. He’s about to be elevated to the Peerage and has chosen the title Lord Tilbury. He also appears in Sam the Sudden. In Summer Lightning, he’s mentioned as the owner of Society Spice, the magazine Percy Pilbeam used to edit.

Norman Murphy (in A Wodehouse Handbook, vol. 1) is convinced that Lord Tilbury is based on Alfred Harmsworth, later Lord Northcliffe. According to him, in 1902, Northcliffe controlled over half the newspapers and magazines in the UK. The newspapers were run from Carmelite House and the magazines from Northcliffe House, both of which were both in Carmelite Street, off Fleet Street.

Lord Tilbury runs his publishing empire from Tilbury House, similarly to how Lord Northcliffe ran his magazine empire from Northcliffe House.

Lady Julia Fish (ch.1, p.5)

One of Lord Emsworth’s ten sisters; widow of Sir Miles Fish; mother of Ronnie Fish, first mentioned in Money for Nothing (1928) and described in more detail in Summer Lightning/Fish Preferred (1929). This is her first appearance “onstage” in a novel. [NM]

Biarritz (ch.1, p.5)

A seaside city in southwestern France. The casino (opened in 1901) and the beaches made it a popular tourist destination starting in the 19th century.

Tiny Tots (ch.1, p.5)

A children’s magazine owned by Lord Tilbury. See ch. 7, p. 71 in Murphy, N. T. P., A Wodehouse Handbook, vol. 1, Revised Second Edition (2013). [In the Saturday Evening Post serialization the magazine is titled Just Tots. —NM]

Reminiscences (ch.1, p.6)

In Summer Lightning, we hear that Galahad is writing his Reminiscences. Lady Constance and Sir Gregory want to stop him from publishing them, and he agrees on the condition that Ronnie Fish be allowed to marry Sue Brown, a chorus girl, the daughter of the late Dolly Henderson, with whom Gally was once in love.

Cor! (ch.1, p.6)

A cockney slang word meaning God.

twenty-five pounds overweight (ch.1, p.6)

Lord Tilbury has grown a bit since Bill the Conqueror. In the first chapter of that book, he’s described as being twenty pounds overweight.

Napoleon (ch.1, p.6)

Napoléon Bonaparte was Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814 and again in 1815. The British press portrayed him as short and round and that has led to the stereotype of a short person who is overly aggressive in order to compensate for an inferiority complex.

[Napoleon Bonaparte was measured at 5′7″ at his death, a bit above the average height of a Frenchman of his era, but much shorter than his bodyguards, who were selected for their size, which apparently led others to think of Napoleon as short. —NM]

every county from Cumberland to Cornwall (ch.1, p.6)

Cumberland is a county in North West England (only Northumberland is farther north), whereas Cornwall is in the south west. A picturesque way of saying ‘all along the length of England’.

long-cupboarded skeletons (ch.1, p.7)

This is Wodehouse’s twist on the idiom ‘skeletons in the cupboard’. In American English, it usually takes the form ‘skeletons in the closet’. It means a set of facts about someone that if revealed might lead to scandal. Apparently these skeletons had been in their cupboards for a long time.

Diego Seguí points us to the Phrase Finder, which traces the literary image back to Thackeray; Diego also mentions several usages in Dickens, including Our Mutual Friend, ch. 4 and 12, and Little Dorrit, ch. 20. Wodehouse used the image often:

And, besides, he really did want to know how Mr. Thompson had got to hear of this skeleton in his cupboard.

The Pothunters, ch. 12 (1902)

“We shall be able to see the skeletons in their cupboards,” he observed. “Every man has a skeleton in his cupboard, which follows him about wherever he goes.”

Clowes, in The Gold Bat, ch. 20 (1904)

“My friendship for you deplores a mammoth skeleton in your cupboard, James.”

Julian Eversleigh in Not George Washington, ch. 9 (1907)

The cupboard, with any skeletons it might contain, was open for all to view.

Mike, ch. 51 (1909)

The closet, with any skeletons it might contain, was open for all to view.

Something New, ch. 9 (1915)

We were peeping into the family cupboard and having a look at the good old skeleton.

Bertie Wooster, in “Sir Roderick Comes to Lunch” (1922; in The Inimitable Jeeves, ch. 7, 1923)

[The Duke of Dunstable] decided to abandon reserve and lay bare the skeleton in his own cupboard.

Uncle Fred in the Springtime, ch. 10 (1939)

“But is that enough?” said Homer, shrinking like a salted snail at the thought of having to reveal the skeleton in the family cupboard, but feeling that if the revelation must be made, this was the moment for a conscientious man to make it.

The Girl in Blue, ch. 3 (1970)

‘A veritable storehouse of diverting anecdote’ (ch.1, p.7)

This seems to be a play on the more common expression ‘a veritable storehouse of knowledge’. It is unknown whether Wodehouse got this from an actual critic’s review.

Sir Gregory Parsloe-Parsloe of Matchingham Hall (ch.1, p.7)

The 7th Baronet had been friendly with Galahad when they were both young men about town. By the time of Summer Lightning, he’s a solid citizen vying for a seat in Parliament.

Recording Angel (ch.1, p.7)

The angel who records all the good and bad deeds committed by men, and presumably these records are used by St. Peter at the pearly gates to decide who gets admitted.

Diego points out an early use by Wodehouse in Love Among the Chickens, ch. 10, in which the argument between Jeremy Garnet and his Conscience is published in the Recording Angel (italicized as if it were a periodical title).

He glanced over his shoulder with a sudden nervous movement, as if expecting to see the Recording Angel standing there with pen and note-book.

Lord Hoddeston, in Big Money, ch. 4.2 (1931)

The whole thing to my mind smacked rather unpleasantly of Abou ben Adhem and Recording Angels, and I found myself frowning somewhat.

Bertie Wooster, upon hearing of the Junior Ganymede Club Book in The Code of the Woosters, ch. 5 (1938)

“Now listen, Uncle Fred,” he said, and his voice was like music to the ears of the Recording Angel, who felt that this was going to be good. “All that stuff is out.”

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 2 (1948)

Society Spice (ch.1, p.7)

A gossip magazine owned by Lord Tilbury which used to be edited by Percy Pilbeam, and (incompetently) by Lord Tilbury’s son Roderick Pyke before him.

Percy Pilbeam (ch.1, p.7)

Percy Frobisher Pilbeam is first introduced in Bill the Conqueror along with Lord Tilbury and his family. He rises to editor of Society Spice before resigning to start a Private Inquiry Agency.

Pilbeam also appears in Sam the Sudden, Summer Lightning/Fish Preferred, Something Fishy, and Frozen Assets/Biffen’s Millions; his visit to Blandings is recalled by Lady Constance in Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

succès de scandale (ch.1, p.7)

French, literally ‘success of scandal’. Something that is successful due to its notoriety or scandalous nature.

dead past (ch.1, p.7)

See Sam the Sudden.

galleon under sail (ch.1, p.8)

A galleon was a large, multi-decked sailing ship used as an armed cargo carrier primarily by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries. This is a shortened form of ‘a galleon under full sail’ which means a galleon with all the sails in position or fully spread. Figuratively used to suggest rapid or unimpeded progress [OED]

the geniality of a trapped wolf (ch.1, p.8)

This vivid metaphor needs no explanation, but deserves an exclamation! [NM]

Admirals in the Swiss Navy (ch.1, p.8)

‘Admiral of the Swiss navy’ is US Armed Forces slang for a self-important person.

War Slang: American Fighting Words & Phrases Since the Civil War, Third Edition by Paul Dickson

[Presumably the doorkeeper at Tilbury House wore a quasi-military uniform, similar to that of the doorman at Barribault’s Hotel, who is described as an admiral in the Ruritanian navy in Spring Fever, ch. 20, and as a Ruritanian Field Marshal in Something Fishy, ch. 9. —NM]

small boys in buttons (ch.1, p.9)

A boy servant in livery (uniform), a page. Akin to an office boy. Essentially someone to run errands in an office or stately home. See also Bill the Conqueror.

time is money (ch.1, p.9)

Wodehouse liked to appropriate slogans and catch-phrases from the world of business, such as Do It Now. Google Books finds “Time is money” as far back as 1719, in The Free-Thinker, no. 121. Dickens made use of it in Barnaby Rudge and Nicholas Nickleby. [NM]

“Time is money, you know, with us business men.”

Archie Moffam to his father-in-law, in “The Man Who Married an Hotel” (1920; in Indiscretions of Archie, 1921)

“We young business men move fast nowadays, Uncle Cooley. Time is money with us.”

Bill West, in Bill the Conqueror.

Time is money with these coves, and no doubt he had remembered some other appointment which he couldn’t make if he waited at his club till ten.

Ukridge, in “A Bit of Luck for Mabel” (1925; in Eggs, Beans and Crumpets)

Smedley, who had been making for the French window, briskly like a man to whom time is money, paused.

The Old Reliable, ch. 19 (1951)

It was brief and business-like, the letter of a man to whom time is money.

French Leave, ch. 7 (1956)

Monty Bodkin (ch.1, p.9)

Montague (or Montrose) Bodkin is Sir Gregory’s nephew. This is his first appearance in the canon, followed by two novels (The Luck of the Bodkins and Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin) in which he’s one of the main male characters.

Swallowing camels and straining at gnats (ch.1, p.9)

Doing something difficult but balking at something much easier.

Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For ye pay tithe of mint and anise and cummin, and have omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy, and faith: these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone. Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel.

Bible: Matthew 23:23–24

The man of iron (ch.1, p.9)

Possibly a reference to Otto von Bismarck, who gave a famous speech in 1862 called the ‘Blood and Iron speech’ while he was Minister President of Prussia. Bismarck was famously strong-willed and outspoken. Lord Tilbury had intended to be ‘strong, brusque, decisive’ with Lady Julia.

placing his thumbs in the armholes of his waistcoat (ch.1, p.10)

This pose, resulting in outspread elbows, is an expression of confidence, whether real or simulated. Lord Tilbury has adopted it in two earlier books, and several other characters have done the same. [NM]

“That,” said Sir George, thrusting his fingers into the armholes of the Pyke waistcoat and speaking in the loud, bluff, honest voice of the man who is about to do some hard lying, “is a photograph of a Miss—Miss——”

Bill the Conqueror, ch. 8 (1924)

And Lord Tilbury, having removed his thumbs from the armholes of his waistcoat in order the more freely to fling them heavenward, uttered a complicated sound…

Sam the Sudden/Sam in the Suburbs, ch. 12.2 (1925)

…a complacent-looking person with a shaven neck and an unlighted cigar, who was leaning back in a swivel-chair with his thumbs in the armholes of his waistcoat.

“The Dramatic Fixer” (1916)

“Is zat so?” Mr. Waddington put his thumbs in the armholes of his waistcoat and felt rather conquering.

Sigsbee Waddington, in The Small Bachelor, ch. 13 (1927)

Mr. Waddington’s thumbs shot into the arm-holes of his waistcoat.

G. G. Waddington, in If I Were You, ch. 8 (1931)

“Speech,” he said affably.

He then stood with his thumbs in the armholes of his waistcoat, waiting for the applause to die down.

Gussie Fink-Nottle, in Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 17 (1934)

But hear it spoken in a loud, rasping, defiant voice by a man with his chin protruding and his thumbs in the armholes of his waistcoat, and the effect is vastly different.

Spring Fever, ch. 23 (1948)

The human race was all right. Any race that could produce a Russell Clutterbuck was entitled to slap itself on the chest and go strutting about with its thumbs in the armholes of its waistcoat and its hat on the side of its head.

French Leave, ch. 8 (1956)

Home for the Lovelorn (ch.1, p.10)

This sounds like a play on the name of an orphanage (home for orphans etc.). Elsewhere in the canon, PGW mentions two other magazines published by Tilbury House: Home Chat in A Damsel in Distress and Pyke’s Home Companion in Sam the Sudden. So maybe Tilbury means that though he publishes various Home magazines, he’s not actually running an asylum for the lovelorn.

Sunny Jim (ch.1, p.11)

Jimmy Dumps is a cartoon character created in 1901 for advertising Force cereal, a wheat flake cereal. He is supposed to be a gloomy person who is transformed into Sunny Jim after eating the cereal.

Jim Dumps was a most unfriendly man,

Who lived his life on the hermit plan;

In his gloomy way he’d gone through life,

And made the most of woe and strife;

Till Force one day was served to him

Since then they’ve called him “Sunny Jim.”

High o’er the fence leaps Sunny Jim,

Force is the food that raises him.

[advertising jingles by Minnie Maud Hanff]

who moves in a mysterious way his wonders to perform (ch.1, p.11)

God moves in a mysterious way

His wonders to perform;

He plants His footsteps in the sea

And rides upon the storm.

William Cowper: God moves in a mysterious way

“I have no notion whatever why he has had this sudden change of heart.” (ch.1, p.11)

Lady Julia apparently has no scruples about lying to Lord Tilbury to hide her knowledge of the bargain made in Summer Lightning that results in Galahad’s suppression of his Reminiscences. [NM]

take him for a ride (ch.1, p.11)

In milder usages, figurative, meaning to deceive. Here it is a jocular reference to gangster slang for an out-of-the-way killing.

But in a sinister and the original sense the person taken for the ride rarely returns. The expression was of underworld origin, coined in the United States during the wave of criminality after World War I, when rival gangs of law-breakers waged warfare on each other. Anyone incurring the displeasure of a gang chieftain was likely to be invited by a henchman to go for a ride in the car of the latter, ostensibly to talk matters over and clear up the misunderstanding. The victim rarely returned from such a trip; his body might later be found by the police—or might not.

Charles Earle Funk: A Hog on Ice (1948, Harper & Row)

punching the clock (ch.1, p.11)

In some workplaces, workers literally punch a timecard using a time clock. But this can also mean doing the minimum necessary to keep the job, i.e., showing up at work for the requisite amount of time but not accomplishing much actual work.

Nature in the raw is seldom mild (ch.1, p.11)

This phrase appeared in several Lucky Strike cigarette advertisements in 1932–33 (Heavy Weather was published in 1933). The ad at right appeared in the December 1932 Popular Mechanics.

Lady Wensleydale (ch.1, p.12)

According to the Bedfordshire Archives & Records Service, there was an actual Lady Wensleydale who died in March 1879. The 1st Baron Wensleydale (born James Parke) was created Baron of Wensleydale, of Wensleydale (a life-peerage) circa 1855. This was later changed to a hereditary peerage as Baron of Wensleydale, of Walton. If this lady was his relict, then her name was Cecilia, not Jane. The Barony of Wensleydale is extinct because the 1st Baron had no male heirs.

Wensleydale is one of the Yorkshire Dales in North Yorkshire, England. It is famous for its cheese by the same name.

It is not known whether Lady (Jane) Wensleydale is based on the lady of that name, or on the cheese.

Norman Murphy suggests in The Reminiscences of Galahad Threepwood that the original for Lady Carnaby/Wensleydale/Bablockhythe is Adeline de Horsey, countess of Cardigan and Lancastre. She was for many years the mistress of Lord Cardigan of the Charge of the Light Brigade, marrying him after the death of his first wife. After his death, she married the Portugese Comte de Lancastre. Her book My Recollections appeared in 1909.

Wensleydale is one of the titles Lord Tilbury considers and decides against in Bill the Conqueror.

Sixty Years Near the Knuckle in Mayfair (ch.1, p.12)

A fictional title. Near the knuckle is an informal British phrase meaning verging on the indecent or offensive. [The US edition of Heavy Weather omitted the reference, so that Lady Wensleydale’s book was just Sixty Years in Mayfair. —NM]

Mayfair is an affluent area in the West End of London. It used to be mainly residential and housed upper class families until World War I, after which many of the largest houses were converted into foreign embassies. It attracted more commercial development after World War II and is now primarily commercial.

Chapter 2

life seemed to steal back to that rigid form (ch.2, p.13)

Perhaps an echo of Victorian cliches; a similar phrase occurs in a sentimental poem about a dying son, “The Mother’s Dream: a true incident” by Mrs. N. A. Pierson:

When suddenly, To the rigid form it seemed that life came back . . .

[Our Monthly, v. 7, p. 407 (June 1873), found by NM]

Though pain and anguish rack the brow (ch.2, p.13)

This was a poem PGW quoted in several of his novels. See Piccadilly Jim, A Damsel in Distress, Summer Moonshine, How Right You Are, Jeeves (ch.13), Three Men and a Maid (ch.7), Very Good, Jeeves (ch.6), Bill the Conqueror, etc.

O, Woman! in our hours of ease,

Uncertain, coy, and hard to please,

And variable as the shade

By the light quivering aspen made;

When pain and anguish wring the brow,

A ministering angel thou!

Sir Walter Scott: Marmion, Canto 6, line 30 (1808)

And here it would be agreeable to leave him (ch.2, p.13)

Could this be a reference to Winnie-The-Pooh? Ch. 10 in The House at Pooh Corner is titled In which Christopher Robin and Pooh come to an enchanted place, and we leave them there. The House at Pooh Corner was published in 1928, Heavy Weather in 1933.

motorman’s glove (ch.2, p.13)

A motorman is a person who operates an electric tram, trolley or train. (S)he’s in charge of the electric motor, similarly to an engineer on a rail engine. A motorman’s glove would probably not taste very good, what with all the motor oil it has to be around.

That’s what puts hair on the chest (ch.2, p.13)

to do or take something to invigorate or energize someone

McGraw-Hill Dictionary of American Idioms (2002)

...like a leaking siphon (ch.2, p.14)

A hissing sound? [No doubt, since the word (spelled “syphon” in some editions including the US first) refers to a bottle for dispensing carbonated water; pressing a lever or button opens a valve, so that the pressure of the gas forces soda water out of the bottle’s spout into the user’s drinking glass. —NM]

the lowdown (ch.2, p.14)

the true facts or relevant information about something [OED]

US magazine and book hyphenate it as low-down; the OED cites the term first from San Francisco newspapers in 1905 and 1915, next from Wodehouse in Leave It to Psmith.

straight from the horse’s mouth (ch.2, p.14)

from an authoritative or dependable source.

mug (ch.2, p.14)

here, a gullible simpleton, a person easily persuaded or taken advantage of (British slang, mid-nineteenth century) [NM]

rummy (ch.2, p.14)

odd, strange, queer [OED]

Hendon (ch.2, p.14)

A London suburb seven miles northwest of Charing Cross, created a Municipal Borough in 1932, and subsumed into the London Borough of Barnet in 1965. [DS/NM]

Stow-in-the-Wold (ch.2, p.14)

Probably Stow-on-the-wold, a small market town in Gloucestershire, England.

lose her shirt (ch.2, p.14)

lose everything she owns on a bet

Ponders End (ch.2, p.14)

a commercial and residential district in the north London Borough of Enfield

popinjay (ch.2, p.14)

Literally a parrot. Figuratively, a vain or conceited person, especially one who dresses extravagantly.

It was a judgement (ch.2, p.14)

To Lord Tilbury, letting himself be worked for a job is a sin.

Fear God, and give glory to him; for the hour of his judgment is come

King James Bible: Revelation 14:6

what a harvest, what a reckoning! (ch.2, p.15)

Further references to Judgement Day, also known as the day of reckoning.

for the time is come for thee to reap; for the harvest of the earth is ripe

King James Bible: Revelation 14:15

lissom (ch.2, p.15)

Adjective used to describe someone who is supple and graceful.

the Drones Club (ch.2, p.15)

A gentlemen’s club in London that PGW used as a recurring location in many stories. The first mention is in Jill the Reckless (1921), and the last in Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin (1972).

spats (ch.2, p.15)

A shortening of spatterdashes or spatter guards. A footwear accessory worn to cover the instep and ankle. Spats were popular in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

one of his minor Marshals (ch.2, p.15)

Napoleon Bonaparte appointed a total of 26 Marshals of the Empire, with 14 of them being appointed in the first promotion in 1804. Some of them were relatively obscure generals who had never held significant commands.

deeps of misunderstanding (ch.2, p.15)

The deepest parts of oceans are often referred to as “the deeps of the ocean.” This is PGW’s variation on ‘seas of misunderstanding.’

Who’s the man that says that we’re all islands shouting lies to each other across seas of misunderstanding?

Rudyard Kipling: The Light that Failed, ch. 5 (1891)

taken his oath (ch.2, p.15)

Similar to ‘could have sworn.’ Historically, people were required to swear on the Bible and take an oath while assuming public office, or while giving evidence in a public court.

Cor! (ch.2, p.16)

A British slang word meaning “God” in cockney English.

elfin personality (ch.2, p.16)

small and delicate, with a mischievous charm.

lad about the metropolis (ch.2, p.16)

variation of ‘man about town.’ PGW coined the phrase but didn’t use it again.

alarm and despondency (ch.2, p.17)

See Ukridge.

the sack (ch.2, p.17)

Custer’s Last Stand (ch.2, p.17)

The most significant battle of the Great Sioux War of 1876 in North America. Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer suffered a significant defeat at the hands of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho (peoples and tribes of Native Americans). Custer was killed in the battle. Colloquially used to signify an all-out last effort in a losing battle.

bradawl (ch.2, p.17)

a hand boring tool similar to a small, sharpened screwdriver

wheels within wheels (ch.2, p.17)

used to indicate that a situation is complicated and affected by secret or indirect influences.

[A literary echo of Ezekiel’s vision:

The appearance of the wheels and their work was like unto the colour of a beryl: and they four had one likeness: and their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel within a wheel.

Bible: Ezekiel 1:16, English Revised Version —NM]

Gertrude Butterwick (ch.2, p.18)

This is Gertrude’s first appearance in the canon. She also appears in The Luck of the Bodkins and Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin.

No clock-watching, no folding of the hands in … (ch.2, p.18)

How long wilt thou sleep, O sluggard? When wilt thou arise out of thy sleep? Yet a little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to sleep: So shall thy poverty come as one that travelleth, and thy want as an armed man.

Bible: Proverbs 6:9–11

No bowels—of compassion (ch.2, p.18)

But whoso hath this world’s good, and seeth his brother have need, and shutteth up his bowels of compassion from him, how dwelleth the love of God in him?

Bible: 1 John 3:17

See Biblia Wodehousiana for Fr. Rob’s commentary.

Pip-pip (ch.2, p.18)

Informal way of saying goodbye.

young aristocrat of the French Revolution stepping into the tumbril (ch.2, p.18)

During the French Revolution (1789–99), people that had been sentenced to death by guillotine were transported to the site of execution by tumbril – an open wooden cart that could be tilted backwards for unloading.

Lizard’s Breath (ch.2, p.19)

A cocktail. The name seems to have been invented by PGW. [The Firefly Hollow Brewing Co. in Bristol, Connecticut, now produces a “massively hoppy” Lizard Breath India Pale Ale, but none of their other offerings have Wodehousean names, so this must be a coincidence. —NM]

Turfed out (ch.2, p.19)

Removed or ejected from a place

Driven into the snow (ch.2, p.19)

Driven into the snow (ch.2, p.19)

For a long time after the arrival of peace they will feel like orphans driven out into the snow.

“Watchman, What of the Night?” in Vanity Fair, April 1916

The whole thing reminded me of one of those melodramas where they drive chappies out of the old homestead into the snow.

“The Aunt and the Sluggard” (1916)

She shot a swift glance sideways, and saw the dark man standing in an attitude rather reminiscent of the stern father of melodrama about to drive his erring daughter out into the snow.

The Adventures of Sally, ch. 2 (1921)

“The idea of anybody doing that absurd driving-into-the-snow business in these days!”

See Leave It to Psmith (1923).

“Driven into the snow before I could so much as set eyes on him.”

See Full Moon, ch. 9.1 (1947).

“I was driven out into the snow. Twine wanted to be alone with his other guest, a man who is interested in his work.”

Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 7 (1957)

drove me out into the snow

See Ice in the Bedroom (1961).

That’s Life (ch.2, p.19)

Life isn’t fair, what happened to you isn’t fair, but you need to accept it and go on. Thought to originate as a translation of the French phrase “C’est la vie.”

not unblessed with the world’s goods (ch.2, p.19)

Wealthy. See the earlier note under bowels of compassion for a Scriptural source.

Perkins and Broster … are both well provided with the world’s goods.

“High Stakes” (1925)

As Earl of Droitwich, Tony would be quite comfortably provided with this world’s goods, but by no means so well provided—what with Death Duties and Land Taxes and all the rest of it—as to be in a position lightly to sever relations with the heiress of Waddington’s Ninety-Seven Soups.

If I Were You, ch. 16 (1931)

“In the course of a lifetime I have contrived to accumulate no small supply of this world’s goods, and if there is any little venture or enterprise for which you require a certain amount of capital——”

“Cats Will Be Cats” (1932; in Mulliner Nights, 1933)

The third Earl of Blicester was a man who, though well blessed with the world’s goods, hated loosening up.

“The Masked Troubadour” (1936; in Lord Emsworth and Others, 1937)

a fellow called Baxter (ch.2, p.20)

Rupert Baxter first appeared in Something Fresh in 1915. Also known as The Efficient Baxter, he’s Lord Emsworth’s secretary and the comic villain that the protagonists have to circumvent to achieve their ends. He reprises this role in Leave It to Psmith. He also appears in Summer Lightning, Uncle Fred in the Springtime, and the long short story “The Crime Wave at Blandings” (collected in Lord Emsworth and Others in the UK and in The Crime Wave at Blandings in the US), and is recalled in Heavy Weather and The Brinkmanship of Galahad Threepwood/Galahad at Blandings.

left ages ago (ch.2, p.20)

At the end of Leave It to Psmith, the second book in the Blandings series.

this business of going to the South of France in the summer (ch.2, p.20)

The French Riviera became a winter resort for the wealthy in the late 18th century, but it was not until the opening of the Train Bleu rail line in 1922 and Coco Chanel’s spearheading the fashion for suntanning in 1923 that the summer season became popular. [NM]

roses and pumpkins (ch.2, p.20)

See “The Custody of the Pumpkin” (1924), collected in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere. [NM]

pigs … Empress of Blandings (ch.2, p.20)

See “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” (1927), collected in Blandings Castle and Elsewhere. [NM]

A bright light had just flashed upon him (ch.2, p.21)

An idea had occurred to him.

See Biblia Wodehousiana for a possible Scriptural source.

Worcestershire … head of the clan (ch.2, p.21)

As we learn in Money for Nothing (1928), Hugo’s uncle Lester Carmody is his trustee and the present occupant of Rudge Hall in Worcestershire. [NM]

the Empress was stolen the other day (ch.2, p.22)

As related in Summer Lightning/Fish Preferred (1929), which takes place about ten days prior to this book in story time, according to Beach’s recollections in ch. 16. But see the discussion of discrepancies at that note and at August, below. [NM]

stone-cold certainties (ch.2, p.23)

A discussion of how the phrase “stone cold” came to mean “complete” is found in the English Language and Usage Stack Exchange blog. [NM]

Othello or green-eyed monster school of thought (ch.2, p.23)

Oh, beware, my lord, of jealousy!

It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock

The meat it feeds on.

Shakespeare: Othello III, iii

trunk call (ch.2, p.24)

A long-distance telephone call, from trunk line, a telephone line connecting two distant exchanges. [NM/Diego]

Chapter 3

Matchingham 8-3 (ch.3, p.25)

Telephone numbers in the UK in the early 1900s had a three-letter exchange code followed by the phone number. The exchange code was usually (but not always) the first three letters of the exchange name. While placing a call through an operator, the practice was to say the full name of the exchange followed by the phone number.

messuages (ch.3, p.25)

A dwelling house with outbuildings and land assigned to its use [OED].

stately home of England (ch.3, p.25)

The stately homes of England

How beautiful they stand!

Amidst their tall ancestral trees,

O’er all the pleasant land!

Felicia Dorothea Hemans (1793–1835): The Homes of England

Diego reminds us that Wodehouse cited the author by name in Full Moon, ch. 6.2 (1947):

“The stately homes of England,” sang the poetess Hemans, who liked them, “how beautiful they stand”; and about the ancient seat of the ninth Earl of Emsworth there was nothing, as far as its exterior was concerned, which would have caused her to modify this view.

and that the phrase often appeared in the titles of books, tourist guides, and magazine series, both in real life (Jewitt & Hall and Geddie) and in Wodehouse’s fiction:

the Stately-Homes-of-England series appearing in the then newly established Pyke’s Home Companion

Sam the Sudden, ch. 2 (1925)

She had read up the Manor, Woollam Chersey, in Stately Homes of England

Doctor Sally, ch. 9 (1932)

Quaker collar (ch.3, p.25)

A broad flat collar of a type characteristically worn by Quakers. A Quaker is a member of the Religious Society of Friends.

twelve-forty train east (ch.3, p.25)

Market Blandings is situated in Shropshire. Norfolk is almost exactly due east from Shropshire.

surging round him like glue (ch.3, p.25)

An unusual metaphor apparently coined by PGW.

talk pig to him (ch.3, p.26)

The pig referred to here is that pre-eminent pig, the Empress of Blandings.

Aunt Constance, Lady Constance Keeble (ch.3, p.26)

One of Lord Emsworth’s ten sisters in the canon.

Last of the Fishes (ch.3, p.26)

Ronnie apparently does not have any brothers, or male cousins or uncles on his late father’s side, who would become head of his branch of the family if he died childless. See also Summer Lightning, ch. 18 (1929) for another similar reference to Ronnie. [NM]

Diego Seguí points out that Bertie Wooster three times refers to himself as the last of the Woosters (Joy in the Morning, ch. 20; Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves, ch. 12; Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen, ch. 15) even though he has cousins (Claude, Eustace, Harold) who would be the male successors to the line (and to the title of Lord Yaxley, after Uncle George hands in his dinner pail) after Bertie’s death. Bertie’s self-styling could be an oversight on his part, a subtle way of mentioning that he has no direct heir, or more likely a pompous inexactitude. The same could hold true for Freddie Rooke (who calls himself “The Last of the Rookes” in The Little Warrior/Jill the Reckless) and Spennie Dreever (“the last of the Dreevers” in The Intrusion of Jimmy/A Gentleman of Leisure, although this is not Spennie’s wording but rather the narrator’s, so perhaps more reliable).

See also Clifford Gandle, “the last of the mad Gandles” (“Mr. Potter Takes a Rest Cure”, 1926); Bill, the last of the Bannisters (Doctor Sally, ch. 13, 1932); Freddie, the last of the Fitch-Fitches (“Romance at Droitgate Spa”, 1937); Lord Uffenham, the last of the Uffenhams (Money in the Bank, ch. 6, 1942); Pongo, the last of the Twistletons (Uncle Dynamite, ch. 9.1, 1949); Barmy, “the Last of the Fotheringay-Phippses” (Barmy in Wonderland, ch. 8, 1952); Freddie, last of the Widgeons (Ice in the Bedroom, ch. 13, 1961); Gussie, the last of the Mortlakes (Do Butlers Burgle Banks, ch. 13, 1968); and Monty, the last of the Bodkins (Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin, ch. 6, 1972).

… a mixed Press. Some of the notices were good, others not. (ch.3, p.26)

Good reviews of plays in the newspapers were called “favorable press notices.” Bad reviews – “unfavorable press notices.” Mixed press meant that some were good and some were not.

Sue’s mother (ch.3, p.26)

Dolly Henderson, the late singing star of music halls, “a little bit of a thing in pink tights, with the jolliest smile you ever saw” in Lord Emsworth’s recollection later in this chapter. First recalled in Summer Lightning, ch. 2 and 18. [NM]

Their views on the importance of rank diverge from those of the poet Burns (ch.3, p.26)

Is there for honest Poverty

That hings his head, an’ a’ that;

The coward slave – we pass him by,

We dare be poor for a’ that!

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

Our toils obscure an’ a’ that,

The rank is but the guinea’s stamp,

The Man’s the gowd for a’ that.

Robert Burns: A Man’s a Man For A’ That (1795)

Blot … upon the escutcheon (ch.3, p.26)

A stain or mark against one’s reputation or that of one’s family. An escutcheon was a heraldic shield that bore a family’s coat of arms, and thus serves as a metaphor for one’s honor. (Source: The Free Dictionary)

To put on dog (ch.3, p.26)

This is an American idiom rather than a British one. It is first recorded in 1871, in a book by L. H. Bagg called Four Years at Yale. One of the meanings is to make things extra formal, which is presumably the sense in which it is used here.

marcelled (ch.3, p.26)

crimped in waves by a heated iron, a process developed by French hairdresser François Marcel [NM]

P. Frobisher Pilbeam (ch.3, p.27)

A.k.a. Percy Pilbeam. First appeared in Bill the Conqueror (1924). [In Summer Lightning he had sent flowers to Sue at her theatre, approached her at her table at Mario’s, and otherwise given Ronnie some cause for jealous feelings. —NM]

Wake the fiend that slept (ch.3, p.27)

PGW presumably means jealousy, though the more accurate reference would be to vengeance.

That voice had pow’r to quell the fiend within,

Whose touch had turn’d his very soul to sin.

That fiend was vengeance; – e’en his virtues bow’d

Before the altar which to vengeance glow’d.

His virtues! yes; for even fiends may boast

A shadow of the glory they have lost, –

But oh! like them, his crimes were dark and deep,

For vengeance was awake, – can vengeance sleep?

Yes; sleep, as tigers sleep, with half-shut eye,

Crouching to spring upon the passer-by,

With parch’d tongue cleaving to his blacken’d cell,

Stiff’ning with thirst, and jaws which hunger fell

Hath sharply whetted, quiv’ring to devour

The reckless wretch abandon’d to his pow’r.

Yes: thus may vengeance sleep in breast like his,

Where thoughts of wild revenge are thoughts of bliss.

Lucretia Maria Davidson: Maritorne, or the Pirate of Mexico (1841)

perisher (ch.3, p.27)

an annoying person, or one regarded as awkward, contemptible, or troublesome. British colloquial citations in the OED date from 1896 onward, including one from Wodehouse’s The Luck of the Bodkins (1935). [NM]

He knew him—one of those good-looking blighters; one of those oiled and curled perishers; one of those blooming fascinators who go about the world making things hard for ugly, honest men with loving hearts. Oh, yes, he knew the milkman.

“The Romance of an Ugly Policeman” (1915; in The Man with Two Left Feet, 1917)

“This bird’s bit me in the finger, and ’ere’s the finger, if you don’t believe me—and I’m going to twist ’is ruddy neck, if all the perishers with white spats in London come messing abart and mucking around, so you take them white spats of yours ’ome and give ’em to the old woman to cook for your Sunday dinner!”

Jill the Reckless/The Little Warrior, ch. 5.2 (1920)

“I like Mr. Twist,” she went on pensively. “He’s what I call a perfect gentleman.”

“He’s what I call a perisher,” said Hash sourly.

Sam the Sudden, ch. 21.1 (1925)

“Anything,” breathed William tenderly, “except that you are going to marry that perisher Franklyn.”

“The Story of William” (1927; in Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927/28)

“But are we going to sit still and let perishers with waxed moustaches burgle the house whenever they feel inclined and not do a thing to bring their gray hairs in sorrow to the grave?”

Money for Nothing, ch. 7.7 (1928)

The lift was crammed with perishers of both sexes—the girls giggling and the men what-what-ing in a carefree manner that made him feel sick.

Big Money, ch. 7.1 (1931)

He knew perfectly well that there was nothing between Sue and this Pilbeam perisher and never had been anything.

Heavy Weather, ch. 3 (1933)

“It must have been a nasty jar for the poor perisher when he found I wasn’t here.”

Right Ho, Jeeves, ch. 1 (1934)

“Well, if you ask me,” he said, “the little perishers won’t be able to make head or tail of it.”

Laughing Gas, ch. 1 (1936)

“If you ask me, they don’t learn the little perishers nothing.”

Albert Peasemarch on Eton education in The Luck of the Bodkins, ch. 15 (1936)

“What the Voice of the People is saying is: ‘Look at that frightful ass Spode swanking about in footer bags! Did you ever in your puff see such a perfect perisher?’ ”

The Code of the Woosters, ch. 7 (1938)

“Most modern young men are squirts and perishers.”

Lord Uffenham in Money in the Bank, ch. 11 (1942)

“He’s a pot-bellied perisher.”

Lord Shortlands of Cosmo Blair in Spring Fever, ch. 3 (1948)

Nothing that he had seen of Constable Potter had tended to build up in his mind the picture of a sort of demon lover for whom women might excusably go wailing through the woods, but he knew that his little friend was deeply attached to this uniformed perisher and his heart bled for her.

Uncle Dynamite, ch. 8 (1948)

“Go to the local on a night like this, when yer’ve seen the light and given that perisher Twine the heave-ho, and hitched on to a splendid young feller whom I can nurse in my bosom?”

[This book:] Lord Uffenham in Something Fishy/The Butler Did It, ch. 16 (1957)

“They’re just a lot of pie-faced young perishers who collect in gangs in these rural parishes.”

The Girl in Blue, ch. 13 (1970)

On the other hand, I must consider the new customers. I can’t just leave the poor perishers to try to puzzle things out for themselves.

Much Obliged, Jeeves, ch. 1 (1971)

Pilbeam blister came to a head (ch.3, p.28)

A particularly evocative phrase. “Came to a head” is a figure of speech meaning that a crisis had been reached in events, but “head” here literally means the part of a boil, pimple, or abscess that is likely to break or burst. Since Ronnie thinks that Pilbeam is a blister, he (Pilbeam, not Ronnie) would naturally “come to a head.”

come the old aristocrat … pursed-lip-and-lorgnette (ch.3, p.28)

Behave haughtily in order to put social inferiors in their place

Queen Elizabeth (ch.3, p.28)

A reference to Queen Elizabeth I, presumably meaning imperious.

his work at the altar rails (ch.3, p.29)

In Anglican weddings, the betrothed couple faces the pastor at the altar rails at the beginning of the wedding service.

Trouble, trouble. A dark lady coming over the water. (ch.3, p.29)

Stock phrases of fortunetellers and crystal-ball gazers. [NM]

They can’t do nothin’ till Martin gets here! (ch.3, p.30)

You can’t do nothing till Martin gets here was a monologue by Bert Williams, recorded in January 1913 and released after his death in 1922. It is available as part of the collection Bert Williams: The Middle Years, 1910–1918, published by Archeophone Records. [It can also be heard at archive.org. —NM]

Cerise (ch.3, p.30)

Deep reddish pink color, from the French for “cherry”

August sun (ch.3, p.31)

Wodehouse seems to have been careless with his timeline. Summer Lightning is stated to have taken place in the middle of July; if it is now ten days later it cannot be August yet. And yet in Chapter 17, Gally tells Clarence that it is August the fourteenth. Thanks to Diego Seguí for pointing out these discrepancies, which seem impossible to reconcile. Fortunately, as with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s slips in the timelines of the Sherlock Holmes stories, the technical details are far less important than the overall effect of the writing.

Berkshire sow (ch.3, p.31)

A rare breed of pig originating in the county of Berkshire, England.

the poet Wordsworth … when he beheld a rainbow in the sky (ch.3, p.32)

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

William Wordsworth: My Heart Leaps Up When I Behold (1802)

the Big Shot (ch.3, p.32)

Term used in 1930s American slang to mean a criminal boss. Here Sir Gregory is the boss.

nobbling the favourite (ch.3, p.32)

A phrase from horse-racing jargon, where an unscrupulous gambler might want to slightly injure or distract the horse most expected to win an upcoming race, just enough to lower its chances without there being a suspicion of dirty work which would change the odds. Bingo Little cites examples from racing fiction in “The Purity of the Turf” (1922). [NM]

Vice-President in charge of Pigs (ch.3, p.33)

Joking reference to prevalence of vice-presidents in American corporations

the Empress’s sanctum (ch.3, p.33)

For sanctum, see Biblia Wodehousiana.

Noblesse oblige (ch.3, p.34)

Of French origin, meaning that “one must act in a fashion that conforms to one’s position and with the reputation that one has earned.” [Wikipedia]

the Tivoli (ch.3, p.36)

In full, the Tivoli Theatre of Varieties in the Strand, one of the leading music halls in London from 1890 to 1914. The building was demolished in 1916. [Wikipedia article]

the Argus (ch.3, p.36)

In Greek mythology, a giant with many eyes, some of which remained open while others slept, so that he was always watchful. A useful metaphor for a supposedly giant firm of private detectives, although in reality Pilbeam was the sole proprietor and investigative agent at this time. [NM]

spurned the grass with a frenzied foot (ch.3, p.37)

Chivalric tales tell of the brave horse “who seemed as if his feet were furnished with wings, so fast he spurned the ground beneath his hoofs” [In the Days of Chivalry, Evelyn Everett-Green (1911)]. This echo of such tales portrays Lady Constance as being impatient with her brother and eager to get on to something else. [NM]

Chapter 4

cedar (ch.4, p.40)

See Leave It to Psmith.

Musketeer of the nineties (ch.4, p.40)

The Gay Nineties (US) / Naughty Nineties (Britain) was a nostalgic name for the 1890s that became common during the 1920s. It is unclear whether the reference is to the Three Musketeers (Alexandre Dumas) or to something else.

painted a gas-lit London red (ch.4, p.40)

London streets were illuminated with gas lamps starting in the early 1800s. Starting in the early 20th century, most of the streetlights were replaced with electric lights but there remain around 1500 gas lamps which are still operational.

Painting the town red is an American slang expression meaning to celebrate in a wild, rowdy manner, especially in a public place.

Vichy water (ch.4, p.40)

Sparkling mineral water from the springs at Vichy, France. The waters from Vichy were believed to have medicinal properties.

A promotional pamphlet advertising their qualities.

German cure resorts (ch.4, p.40)

A number of German resorts were popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for treatment of various ailments with thermal waters a.k.a. hot springs. Some of the well-known ones include Baden Baden and Wiesbaden. Baden Baden, for instance, has a long history as a hot springs spa, starting in Roman times and continuing until modern times.

bath-chair (ch.4, p.40)

bath-chair (ch.4, p.40)

a wheelchair, esp. of the hooded kind used by invalids visiting the spas at Bath, England; not “a chair for bathing in”!

The Old Guard which dies but does not surrender (ch.4, p.40)

Pierre Jacques Étienne Cambronne, later Pierre, Viscount Cambronne, General of the French Empire is reported to have said this during the Battle of Waterloo.

At the battle’s conclusion, Cambronne was commanding the last of the Old Guard when General Colville called on him to surrender. According to a journalist named Rougement, Cambronne replied: “La garde meurt et ne se rend pas!” (“The Guard dies and does not surrender!”)

In a world so full of beautiful things, where he felt we should all be as happy as kings (ch.4, p.40–41)

PGW is paraphrasing here. The original couplet is by R. L. Stevenson.

25. Happy Thought

The World is so full of a number of things,

I’m sure we should all be as happy as kings.

: A Child’s Garden of Verses (1905)

biffing (ch.4, p.41)

From biff: a blow, whack; slang from 1889 on, derived from earlier usage as an interjection or onomatopoetic spelling of the sound one makes when receiving a punch. [NM]

pineapple bomb (ch.4, p.41)

Pineapple-shaped hand grenades were used by both British and American military. The British version was called the Mills bomb and the American version was called Mk 2 or Mk II.

Old Pelican Club (ch.4, p.43)

The Pelican Club was “the most raffish of London clubs, which flourished from 1887 to 1892.” Norman Murphy has a wealth of detail about the club’s history and its members in his Handbook.

: A Wodehouse Handbook, Volume One: The World of Wodehouse (2013), pp. 43–50

Only God can make a tree (ch.4, p.43)

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

: Trees (1913)

Mister Bones (ch.4, p.44)

One of the three main characters in an American “minstrel show” or “minstrelsy”. Mr. Bones was played by a white male in blackface and rattled the ‘bones’ (a pair of clappers). Mr. Tambo (also in blackface) played the tambourine, and the interlocutor (in whiteface) asked the questions.

https://www.britannica.com/art/minstrel-show#ref1067244

http://twain.lib.virginia.edu/huckfinn/minstrl.html

See also Thank You, Jeeves. (1934)

Carved up in letters of gold over the door of every school and college (ch.4, p.45)

At Dulwich College, which PGW attended from 1894 to 1900, there was and is a Latin inscription carved into a tablet of black marble over the door of the College chapel (in the center of the original Dulwich buildings, half a mile from the mid-19th-century campus buildings better known today). The author of the inscription was the Rev. James Hume, Schoolmaster of the College from 1706 to 1730. “Some trace of gold colouring” can still be seen in the incised letters.

Regnante Jacobo,

Primo Totius Britanniæ Monarcha;

Edvardus Alleyn Armiger,

Theromachiæ Regiæ Præfectus,

Theatri Fortunæ dicti choragus,

Ævique sui Roscius,

Hoc Collegium instituit;

Atque ad Duodecim Senes egenos

Sex scilicet Viros et totidem Fœminas

Commode sustentandos,

Paremque Puerorum numerum alendum,

Et in Christi Disciplina et bonis moribus Erudiendum,

Re satis ampla instruxit.

Porro,

Ne quod Deo dicaverat postmodum frustra fieret

Sedulo cavit.

Diplomate namque Regis munitus, jussit

Ut a Magistro, Custode, et Quatuor Sociis,

Qui et Conscientiæ vinculis astricti,

Et sua ipsorum utilitate admoniti,

Rem bene Administrarent,

In perpetuum regeretur.

Postquam annos bene multos Collegio suo præfuisset

Dierum tandem et bonorum operum Satur,

Fato concessit,

VII° Cal. Decbris, A. D. MDCXXVI.

“Beatus ille qui misertus est pauperum.”

“Abi tu, et fac similiter.”

We are indebted to Dr. Neil Croally of Dulwich for most of the following translation, as well as to librarian Paul Fletcher, archivist C. M. Lucy, and Diego Seguí for research assistance:

During the reign of James I, monarch of all Britain,

Edward Alleyn, shield-bearer, [i.e. gentleman]

Master of the Royal Beast Fights,

Actor-manager of the Theatre named Fortune,

Of his age the Roscius,

Founded this College;

And properly to support 12 needy elders,

That is, six men and as many women,

And to nurture an equal number of boys,

To be educated in the discipline of Christ and good character,

He organized the college with sufficient, ample resource.

Furthermore,

So that what he had dedicated to God might not later be in vain,

He took zealous precautions.

For, fortified by a letter of authority from the king, he ordered that

the College should be ruled in perpetuity

by a Master, a Warden and four Fellows,

Who constrained by the chains of conscience,

And advised by the benefit to themselves

Would administer the thing well.

After he had well led his college for many years,

At last sated with days and good works,

He yielded to fate

On November 25th, 1626 A.D.

“Blessed is he who takes pity on the poor.”

“Go thou and do likewise.”

: The Environs of London: Volume 1, County of Surrey (1792), pp. 105-117

: The History of Dulwich College, Volume 1 (1889), p.216, p.466

: Dulwich College and Edward Alleyn (1877), p.74

put it on the spot (ch.4, p.45)

To “put someone on the spot” means to place them in a difficult situation (since 1928).

Wivenhoe’s pig (ch.4, p.46)

Gally first recounts the story in Summer Lightning (1929), repeats it here, and adds additional details in chapter 17, below, Full Moon (1947), Pigs Have Wings (1952), and Galahad at Blandings/The Brinkmanship of Galahad Threepwood (1965). [NM]

found some formula (ch.4, p.46)

In the sense of diplomatic agreements which usually follow prescribed standard wording called formulas / formulae.

cat’s paw (ch.4, p.46)

A person used as a tool by another to accomplish a purpose. [OED]

touch of Auld Lang Syne (ch.4, p.47)

The song is generally interpreted as a call to remember old friendships.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and auld lang syne?

: Auld Lang Syne (1788)

a sort of awful Eton and Cambridge silence (ch.4, p.47)

Besides their undoubted academic excellence, great public schools like Eton and universities such as Oxford and Cambridge were thought of as reinforcers of the social codes of British gentlemen, including reticence in showing emotion and keeping a “stiff upper lip” spirit in adversity. Sue here is attributing Ronnie’s formality in difficult circumstances to his educational background. Later, on the roof in Chapter 7, these institutions are mentioned again, as well as in the narrator’s voice in Chapter 9 when Ronnie sees the tattoo on Monty’s chest, and soon after has a difficult conversation with Sue.

world’s great romances (ch.4, p.48)

Among the books with this title are an eight-volume series published in 1911–13 by Thomas Nelson, Edinburgh, a 1918 anthology published by the Henry Altemus Company, Philadelphia, and a 1929 collection of short stories published by Walter J. Black, New York. No doubt other publishers have used this appealing title as well. [NM]

Pitch it strong (ch.4, p.48)

A baseball idiom. A strong pitch is a good (fast and accurate) throw of the ball by the pitcher.

[Alternatively, it could mean “make your speech persuasive” like a salesman’s pitch. —NM]

to make heavy weather (ch.4, p.49)

to allow one’s emotions to be stormy; to make a fuss about something, especially something unimportant. The OED’s first citation is from Wodehouse’s sometime collaborator Ian Hay in 1915. Here, Ronnie’s jealousy is the cause of the storm. [NM]

Chapter 5

Paddington station (ch.5, p.50)

See Uncle Fred in the Springtime.

Berkeley Hotel (ch.5, p.50)

A deluxe hotel, at the time located on the corner of Piccadilly and Berkeley Street, London, opened in 1867 and renamed the Berkeley in 1897. In the 1920s it became one of the first London hotels to be air-conditioned. The present hotel at Wilton Place, Knightsbridge, dates from 1972.

regard the dear old days as a sealed book (ch.5, p.50)

Meaning they will not talk about the past. A sealed book is one that cannot be opened or read.

See Biblia Wodehousiana.

And the vision of all is become unto you as the words of a book that is sealed, which men deliver to one that is learned, saying, Read this, I pray thee: and he saith, I cannot; for it is sealed.

Bible: Isaiah 29:11

But thou, O Daniel, shut up the words, and seal the book, even to the time of the end: many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased.

Bible: Daniel 12:4

high-powered shell (ch.5, p.50)

That is, an artillery shell of high explosive power.

truite bleue (ch.5, p.50)

A delicacy that is also known as truite au bleu. Refers to trout that is so fresh that it turns blue when it is cooked. One method is to start with live trout, club it on the head, remove the internal organs, poach in hot court-bouillon (a special broth used for poaching fish and seafood) in a special fish kettle and serve immediately.

Secret of a happy and successful married life (ch.5, p.51)

One would have thought this more appropriate coming from Uncle Fred than from Monty. [NM]

On appro. (ch.5, p.52)

On approval. A purchase on appro. means that the customer may return it for a refund if not satisfied after a trial use or examination.

wheels within wheels (ch.5, p.52)

See above.

the course of true love (ch.5, p.52)

See Summer Lightning (title of chapter 2).

ankled (ch.5, p.53)

1920s slang for “walked”; OED cites one 1926 source, then the 1930 Wodehouse–Ian Hay play Baa, Baa, Black Sheep and Wodehouse’s 1932 novel Hot Water:

Ankling into the hospital and eating my grapes…

how I earned my living (ch.5, p.53)

We will learn later in this conversation that Monty has money of his own, and in Chapter Six just how wealthy he is.

doing the dirty on Father (ch.5, p.53)

That is, double-crossing him or going against his wishes; playing him a dirty trick. OED records this as World War One slang for dishonourable war tactics, with no sexual connotations. [NM]

formed a hollow square and drummed me out (ch.5, p.53)

A hollow square is an infantry formation that was popular in the 18th and 19th century. Drumming out refers to a dishonorable discharge from the military to the sound of drums. This is an example of PGW combining two images to form a more evocative one.

fairy gold (ch.5, p.53)

Money supposedly given by fairies that turns into rubbish when put to use.

Dead Sea fruit (ch.5, p.53)

Something that appears to be beautiful or full of promise but is in reality nothing but illusion and disappointment.

The man who makes himself a slave to gold is a miserable wretch indeed, winning for his prize the “Dead Sea apple” — golden without, but ashes within.

: British Columbia and Vancouver’s Island, Comprising a Description of These Dependencies (1862)

See also Biblia Wodehousiana.

look on the bright side ... spot the blue bird (ch.5, p.54)

Be optimistic or cheerful in spite of difficulties. See Galahad at Blandings.

The OED defines bluebird as a symbol of happiness. In 1908, Maurice Maeterlink published a stage play named The Blue Bird, which was immensely popular in London. This probably originated the idiom. From the programme for the revival of the play at London’s Haymarket Theatre in 1912: “The Blue Bird, inhabitant of the pays bleu, the fabulous blue country of our dreams, is an ancient symbol in the folk-lore of Lorraine, and stands for happiness.”

pig-conscious (ch.5, p.54)

The use of “-conscious” in making compounds like self-conscious arose in the 19th century, but this sort of formation implying special attention or devotion to an object or activity seems to have been newer at the time of writing. The OED cites “money-conscious” from 1933 and “chess-conscious” from 1938, for example. An advertising journal from 1925 notes that “advertising has made [America] tooth conscious.”

Compare Parsloe-conscious in Summer Lightning. [NM]

biting the bullet (ch.5, p.54)

endure a painful or otherwise unpleasant situation that is seen as unavoidable.

“Steady, Dickie, steady!” said the deep voice in his ear, and the grip tightened. “Bite on the bullet, old man, and don’t let them think you’re afraid.”

: The Light That Failed (1891)

Lady Di (ch.5, p.55)

Probably a reference to Lady Diana Sartoris, known as Lady Di, from the melodrama The Whip by Cecil Raleigh and Henry Hamilton. First produced at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, London, in 1909 where it ran for nearly 400 performances, despite featuring a horse race on stage with real horses! Lady Di was the deputy of the Beverly (fox) hunt. It was also performed on tour, opened to New York in 1912, toured the US for many years and was made into a film in 1917 and 1928. There’s a good chance PGW saw one of these. [The name derives from the Roman moon-goddess Diana, patroness of hunting.]

“O Perfect Love” (ch.5, p.55)

Popular hymn sung at weddings; music by Joseph Barnby; lyric by Dorothy F. Gurney (1883):

O perfect Love, all human thought transcending,

lowly we kneel in prayer before thy throne,

that theirs may be the love which knows no ending,

whom thou in sacred vow dost join in one.

sands are running out (ch.5, p.55)

The phrase refers to an hourglass, in which sand trickles from the top of the hourglass to the bottom through an opening until it has run out.

pip emma (ch.5, p.55)

PM, afternoon hours. From pip (“P”) + emma (“M”) in RAF WWI signalese.

laddishiong (ch.5, p.56)

L’addition — French for ‘the bill’ as transliterated in some textbooks for English-speakers unfamiliar with the nasalized French pronunciation of -on.

working up to a crescendo (ch.5, p.56)

As all musicians are aware, crescendo literally means “increasing” in Italian, and technically refers to the “working up”—to the gradual increase in volume—rather than to the peak of the intensity. Wodehouse generally uses the less-exact sense referring to the climax itself, but is joined by other good writers (including F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby) in the loose usage. [NM]

preux chevalier (ch.5, p.57)

a gallant knight. From French.

barked the skin (ch.5, p.57)

A misprint in Penguin and other recent reprints. Original editions (both US and UK) read “barked the shin” here: that is, scraped the skin at the front of the lower leg. [NM]

daughter of a hundred earls (ch.5, p.57)

Lady Clara Vere de Vere,

Of me you shall not win renown;

You thought to break a country heart

For pastime, ere you went to town.

At me you smiled, but unbeguiled

I saw the snare, and I retired:

The daughter of a hundred Earls,

You are not one to be desired.

: Lady Clara Vere de Vere (1842)

unfortunate Hindu beneath the wheels of Juggernaut (ch.5, p.57)

In the early 14th century, Franciscan missionary Friar Odoric brought to Europe the story of an enormous carriage that carried an image of the Hindu god Vishnu (whose title was Jagannath, literally, “lord of the world”) through the streets of India in religious processions. Odoric reported that some worshippers deliberately allowed themselves to be crushed beneath the vehicle’s wheels as a sacrifice to Vishnu. That story was probably an exaggeration or misinterpretation of actual events, but it spread throughout Europe anyway. The tale caught the imagination of English listeners, and by the 19th century, they were using juggernaut to refer to any massive vehicle (such as a steam locomotive) or to any other enormous entity with powerful crushing capabilities.

(From merriam-webster.com)

his Moscow (ch.5, p.58)

An utter defeat; referring to Napoleon’s rout in trying to conquer Russia in 1812.

breach of promise actions (ch.5, p.58)

From at least the Middle Ages until the early 20th century, a man’s promise of engagement to marry a woman was considered, in many jurisdictions, a legally binding contract. If the man were to subsequently change his mind, he would be said to be in “breach” of this promise and subject to litigation for damages.

cut by the county (ch.5, p.59)

Ignored socially by the upper-class residents of the county.

Possibly a reference to the book by that name, written by Mary Elizabeth Braddon, who is famous for writing Lady Audley’s Secret and other sensational novels in the mid- to late 19th century.

wrought in vain (ch.5, p.59)

The phrase appears in an untitled poem by T. K. Hervey on the topic of Athens. The poem is included in a collection by Hugh William Williams called Select Views in Greece, Volume 1 (1829), p.77.

Thine own blue hill,—where time and Turk have wrought

In vain to break the charm that lingers still,—

Diego Seguí points out that an earlier and better-known example is Dr. Johnson’s tragedy Irene, III, 10:

Sure heaven, for wonders are not wrought in vain,

That joins us thus, will never part us more.

The phrase may perhaps be too common to be linked to a specific source. [DS]

a man of affairs (ch.5, p.60)

A “man of affairs” is a businessman, especially an owner or executive. The term caught on in the late nineteenth century, especially in America. Nothing in the sense of romantic affairs is implied. [NM]

a shade below par (ch.5, p.61)

Not feeling as well as normal. This is not the more common sense relating to golf, in which par is the number of strokes a first-class player should normally require for a particular hole or course. This is a figurative allusion to its meaning in finance, in which par is the nominal or face value of a security, so an investment that is below par is trading at a loss.

velvet hand beneath the iron glove (ch.5, p.61)

Also said by Bertie Wooster in chapter 2 of The Code of the Woosters and Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves.

So much deadlier than the male (ch.5, p.62)

When the Himalayan peasant meets the he-bear in his pride,

He shouts to scare the monster, who will often turn aside.

But the she-bear thus accosted rends the peasant tooth and nail.

For the female of the species is more deadly than the male.

: The Female of the Species (1911)

snakes of the first water (ch.5, p.62)

A play on ‘diamond of the first water’.

According to Wikipedia: The clarity of diamonds is assessed by their translucence; the more like water, the higher the quality. The 1753 edition of Chambers’ Encyclopedia states “The first water in Diamonds means the greatest purity and perfection of their complexion, which ought to be that of the clearest drop of water.”Chapter 6

two forty-five (ch.6, p.63)

One of various trains from London to Blandings that PGW refers to in the various novels. Chapter 5 makes it clear that this one is an express, not stopping at every little station, but it may seem surprising that Market Blandings is large enough to be served by an express train. This topic deserves an essay of its own.

Mendelssohn’s well-known march (ch.6, p.63)

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) composed his Wedding March in C Major in 1842 as part of a suite of incidental music to Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It is a popular wedding march, often used as a recessional as the newlyweds depart, and is at least as often heard arranged for a church organ as in its original orchestral version.

Wilt thou, Robinson, take this Ronald to Blandings Castle? (ch.6, p.63)

A reference to the wording of Anglican wedding vows.

crepe-de-Chine (ch.6, p.63)

A lightweight fabric of silk or silk/wool blend with a plain weave and a crisp appearance. [NM]

perfect butterfly shape (ch.6, p.63)

Jeeves tells Bertie in “Jeeves and the Impending Doom” (1926) that “One aims at the perfect butterfly effect.” In Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, ch. 11 (1954), “One aims at the perfect butterfly shape.” [NM]

old familiar juice (ch.6, p.63)

Alcohol, of course. Here, a reference to pre-dinner cocktails.

Diego finds the source in the FitzGerald translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám:

“Well,” murmur’d one, “Let whoso make or buy,

My Clay with long Oblivion is gone dry:

But fill me with the old familiar Juice,

Methinks I might recover by and by.”

The above is from the fourth English edition of FitzGerald’s version, stanza LXXXIX. Noel Bushnell alerted us to a different version from FitzGerald’s first edition of 1859, in which stanza LXV reads:

Then said another with a long-drawn Sigh,

“My Clay with long oblivion is gone dry:

“But, fill me with the old familiar Juice,

“Methinks I might recover by-and-bye.”

See also Right Ho, Jeeves. Ian Michaud notes that ‘the old familiar juice’ can also be found in Barmy in Wonderland/Angel Cake, Pigs Have Wings, and Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit/Bertie Wooster Sees It Through.

For more comparison between FitzGerald’s editions, see a comprehensive edition, courtesy of the Internet Archive. [NM]

“I must go and put on a white tie” (ch.6, p.64)

This chapter is the clearest example of the two types of evening dress in Wodehouse. Ronnie has just learned from Beach that guests are expected for dinner; when he thought that it was merely a family dinner, he put on a black tie, which only goes with a dinner jacket (US: tuxedo), a semi-formal style of evening wear. He now realizes that the full formality of “white tie” is required: a black tailcoat, a white waistcoat and tie, the full “soup and fish” as Wodehouse likes to call it, named from the first two courses of a formal dinner. [NM]

Heavyweight jinn, stirred to activity by the rubbing of a lamp (ch.6, p.64)

Like Aladdin and the magic lamp. Jinn is a loan word from Arabic where it is a plural noun meaning supernatural spirits. It is commonly anglicized as genies.

resident patients (ch.6, p.65)

Ronnie is comparing Blandings Castle to a clinic or sanatorium, perhaps suggesting that all is not quite normal with the members of his family. [NM]

fifteen thousand a year (ch.6, p.65)

The Bank of England inflation calculator suggests a factor of about 73 for the increase in the cost of goods and services from 1933 to 2020. This suggests that Monty’s invested capital is bringing him an annual income with a buying power equivalent to over £1 million today. [NM]

dagger in his bosom (ch.6, p.65)

In medieval times (up to the 17th century), women sometimes carried concealed knives or daggers inside their bodices for self-protection. Here Ronnie means something else, more like a pang of jealousy. A more poetic way of saying ‘knife through the heart’.

His lips were sealed (ch.6, p.66)

He could not say what he would have liked to.

Madam, I had rather seal my lips

Than to my peril speak that which is not.

: Antony and Cleopatra, Act 5, Scene 2

If you dare to lift up your finger and say “Tweet-tweet, shush-shush, come-come,” (ch.6, p.68)

I lift up my finger and I say

“Tweet tweet, shush shush, now now, come come”

And there’s no need to linger when I say

“Tweet tweet, shush shush, now now, come come”

: from the musical comedy Love Lies (1929)

It seems only the other day that my poor father… (ch.6, p.69)

You will find the details elsewhere in the archives, specifically in Summer Lightning (Fish Preferred), chapter II, § ii, and chapters XVIII–XIX.

Painted hussies (ch.6, p.69)

Hussy actually derives from hussive meaning housewife, but over time has evolved into a derogatory term meaning a brazen, immoral woman or impudent girl. Painted here refers to the fact that in the early 19th century, respectable women did not use makeup but actresses and singers did.

Fine old crusted family rows (ch.6, p.71)

Like fine old crusted port.

war-horse to start at the sound of the bugle… (ch.6, p.71)

Fr. Rob Bovendeaard’s Biblia Wodehousiana traces this to the Bible [Job 39:25] without identifying a specific translation. However, the U.S cavalry had a well-defined set of bugle calls by 1867. A number of them were meant to be sounded while the soldiers were riding to direct them to change pace or direction. For more, see https://www.secondcavalry.net/bugle-calls.

“That tie!” (ch.6, p.71)

As discussed above, “tie” whether white or black was and is used as a shorthand way of referring to formal or semi-formal evening wear. [NM]

Poison was running through his veins (ch.6, p.71)

As with the next reference, this is a description of the physical effects of Ronnie’s jealousy, induced by Lady Julia’s insinuations about Sue’s supposed unfaithfulness. One assumes that a similar phrase in an Alice Cooper rock lyric from 1989 is a coincidence; no common literary source has been found. [NM]

Green-eyed devils were shrieking mockery (ch.6, p.71)

Iago.

Oh, beware, my lord, of jealousy!

It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock

The meat it feeds on. That cuckold lives in bliss

Who, certain of his fate, loves not his wronger,

But, oh, what damnèd minutes tells he o’er

Who dotes, yet doubts—suspects, yet soundly loves!

As if somebody had touched Othello on the arm as he poised the pillow (ch.6, p.71–72)

The murder scene in Othello where he kills Desdemona. Shakespeare only says:

He stifles her.

see him steadily and see him whole (ch.6, p.74)

“I don’t suppose that there are forty million people in England who think more highly of Galahad than I do.” (ch.6, p.76)

The estimated population of England and Wales combined in mid-1933 was 40,350,000; some two and a half million lived in Wales, leaving fewer than 38 million in England. So in a roundabout way Lady Julia is admitting the fact that nearly everyone else thinks more highly of Galahad than she does. [NM]

“Galahad’s daughter, too?” (ch.6, p.77)

Perhaps the only instance in Wodehouse of someone seriously suggesting the possibility of childbirth outside marriage when discussing current-day characters. Julia confronts Galahad with this question point-blank in Chapter 10; his reply proves the impossibility of the suggestion. [NM]

something about some prawns (ch.6, p.78)

I have to think that Wodehouse was deliberately tantalizing his audience with an untold story in homage to his friend Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who had Doctor Watson tease us with allusions to the singular affair of the aluminium crutch as well as the story of the giant rat of Sumatra, for which the world is not yet prepared. [NM]

completed his toilet (ch.6, p.79)

That is, finished dressing. See Right Ho, Jeeves.

Unionist (ch.6, p.80)

This party had nothing to do with labor unions. Unionists favored keeping Ireland within Great Britain, forming a split within the Liberal party when Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone began supporting Irish Home Rule in 1886. Many Unionists joined into a coalition with the Conservative party; by 1912 most had joined a merged Conservative and Unionist party, though after Irish independence in 1922 the party would generally be referred to merely as Conservative. Wodehouse often labels his parliamentary candidates as Unionist, for instance Mr. Bickersdyke in Psmith in the City; if the events of the present novel are intended to be post-1922, Unionist is a slightly anachronistic label. Certainly, as the remainder of the paragraph implies, Sir Gregory is wishing to appeal to the more conservative element among his neighbors. [NM]

Bridgeford and Shifley (ch.6, p.80)

See Summer Lightning.

a buck of the Regency days (ch.6, p.80)

See Summer Lightning.

a small, brilliantined head (ch.6, p.80)

See Leave It to Psmith.

Chapter 7

the battlements of Blandings Castle (ch.7, p.84)

Norman Murphy places the original of Blandings Castle as Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire, though the grounds are based on Weston Park in Shropshire (A Wodehouse Handbook, vol. 1, ch. 39).

Aerial photo of Sudeley Castle (opens in new tab or window)under a leaden sky (ch.7, p.84)

The figurative use of the adjective to mean “dull grey” like the color of lead, the metal, goes back at least as far as Chaucer. The additional connotation of heaviness makes this even more evocative of the oppressive character of the impending storm. [NM]

spinneys (ch.7, p.84)

Small clumps of trees.

witches lived in crooked little cottages (ch.7, p.84)

A possible reference to Hansel and Gretel.

cows with secret sorrows (ch.7, p.84)

See The Mating Season.

slouch-hatted (ch.7, p.85)

A slouch hat is a wide-brimmed hat of felt or cloth, often with one side of the brim turned up; often associated with military and police uniforms.

Details and images at Wikipedia.

I wouldn’t know a clue if you brought me one on a skewer (ch.7, p.85)

A play on “handed on a silver platter” meaning given to someone easily, without them having to work for it.

my first cigar … where I was sick (ch.7, p.85)

In “Jeeves Takes Charge” Bertie Wooster recollects being in need of “solitude and repose” after a cigar when he was fifteen. Young Gussie Rastrick in “Against the Clock” has a bad reaction to a strong cigar. In “The Improbabilities of Fiction” the archetypal villain of a school story “must and will have gin … and a cigar; and it must be a bad one, too, because the public expects me to be ill after it.”

One wonders whether Wodehouse himself had a similar experience as a youth. [NM]