The Captain, July 1908

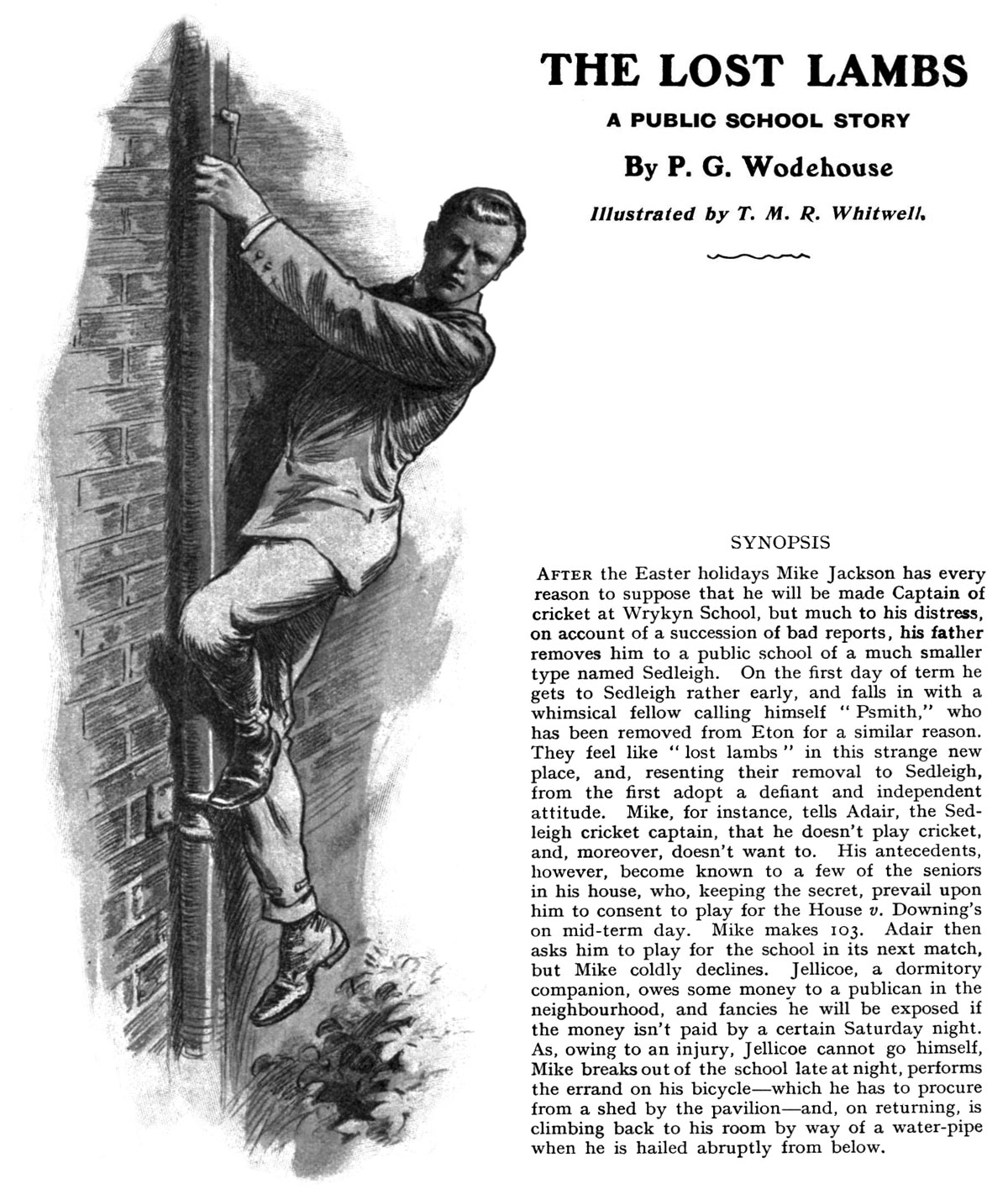

CHAPTER XVI.

pursuit.

HESE things are Life’s Little

Difficulties. One can never tell precisely how

one will act in a sudden emergency. The right

thing for Mike to have done at this crisis was to

have ignored the voice, carried on up the water-pipe,

and through the study window, and gone to bed.

It was extremely unlikely that anybody could have recognised

him at night against the dark background of the house.

The position then would have been that somebody in

Mr. Outwood’s house had been seen breaking in

after lights-out; but it would have been very difficult

for the authorities to have narrowed the search down

any further than that. There were thirty-four

boys in Outwood’s, of whom about fourteen were

much the same size and build as Mike.

HESE things are Life’s Little

Difficulties. One can never tell precisely how

one will act in a sudden emergency. The right

thing for Mike to have done at this crisis was to

have ignored the voice, carried on up the water-pipe,

and through the study window, and gone to bed.

It was extremely unlikely that anybody could have recognised

him at night against the dark background of the house.

The position then would have been that somebody in

Mr. Outwood’s house had been seen breaking in

after lights-out; but it would have been very difficult

for the authorities to have narrowed the search down

any further than that. There were thirty-four

boys in Outwood’s, of whom about fourteen were

much the same size and build as Mike.

The suddenness, however, of the call caused Mike to lose his head. He made the strategic error of sliding rapidly down the pipe, and running.

There were two gates to Mr. Outwood’s front garden. The carriage drive ran in a semicircle, of which the house was the centre. It was from the right-hand gate, nearest to Mr. Downing’s house, that the voice had come, and, as Mike came to the ground, he saw a stout figure galloping towards him from that direction. He bolted like a rabbit for the other gate. As he did so, his pursuer again gave tongue.

“Oo-oo-oo yer!” was the exact remark.

Whereby Mike recognised him as the school sergeant. “Oo-oo-oo yer!” was that militant gentleman’s habitual way of beginning a conversation.

With this knowledge, Mike felt easier in his mind. Sergeant Collard was a man of many fine qualities (notably a talent for what he was wont to call “spott’n,” a mysterious gift which he exercised on the rifle range), but he could not run. There had been a time in his hot youth when he had sprinted like an untamed mustang in pursuit of volatile Pathans in Indian hill wars, but Time, increasing his girth, had taken from him the taste for such exercise. When he moved now it was at a stately walk. The fact that he ran to-night showed how the excitement of the chase had entered into his blood.

“Oo-oo-oo yer!” he shouted again, as Mike, passing through the gate, turned into the road that led to the school. Mike’s attentive ear noted that the bright speech was a shade more puffily delivered this time. He began to feel that this was not such bad fun after all. He would have liked to be in bed, but, if that was out of the question, this was certainly the next best thing.

He ran on, taking things easily, with the sergeant panting in his wake, till he reached the entrance to the school grounds. He dashed in and took cover behind a tree.

Presently the sergeant turned the corner, going badly and evidently cured of a good deal of the fever of the chase. Mike heard him toil on for a few yards and then stop. A sound of panting was borne to him.

Then the sound of footsteps returning, this time at a walk. They passed the gate and went on down the road.

The pursuer had given the thing up.

Mike waited for several minutes behind his tree. His programme now was simple. He would give Sergeant Collard about half an hour, in case the latter took it into his head to “guard home” by waiting at the gate. Then he would trot softly back, shoot up the water-pipe once more, and so to bed. It had just struck a quarter to something—twelve, he supposed—on the school clock. He would wait till a quarter past.

Meanwhile, there was nothing to be gained from lurking behind a tree. He left his cover, and started to stroll in the direction of the pavilion. Having arrived there, he sat on the steps, looking out on to the cricket field.

His thoughts were miles away, at Wrykyn, when he was recalled to Sedleigh by the sound of somebody running. Focussing his gaze, he saw a dim figure moving rapidly across the cricket field straight for him.

His first impression, that he had been seen and followed, disappeared as the runner, instead of making for the pavilion, turned aside, and stopped at the door of the bicycle shed. Like Mike, he was evidently possessed of a key, for Mike heard it grate in the lock. At this point he left the pavilion and hailed his fellow rambler by night in a cautious undertone.

The other appeared startled.

“Who the dickens is that?” he asked. “Is that you, Jackson?”

Mike recognised Adair’s voice. The last person he would have expected to meet at midnight obviously on the point of going for a bicycle ride.

“What are you doing out here, Jackson?”

“What are you, if it comes to that?”

Adair was lighting his lamp.

“I’m going for the doctor. One of the chaps in our house is bad.”

“Oh!”

“What are you doing out here?”

“Just been for a stroll.”

“Hadn’t you better be getting back?”

“Plenty of time.”

“I suppose you think you’re doing something tremendously brave and dashing?”

“Hadn’t you better be going to the doctor?”

“If you want to know what I think——”

“I don’t. So long.”

Mike turned away, whistling between his teeth. After a moment’s pause, Adair rode off. Mike saw his light pass across the field and through the gate. The school clock struck the quarter.

It seemed to Mike that Sergeant Collard, even if he had started to wait for him at the house, would not keep up the vigil for more than half an hour. He would be safe now in trying for home again.

He walked in that direction.

Now it happened that Mr. Downing, aroused from his first sleep by the news, conveyed to him by Adair, that MacPhee, one of the junior members of Adair’s dormitory, was groaning and exhibiting other symptoms of acute illness, was disturbed in his mind. Most housemasters feel uneasy in the event of illness in their houses, and Mr. Downing was apt to get jumpy beyond the ordinary on such occasions. All that was wrong with MacPhee, as a matter of fact, was a very fair stomach-ache, the direct and legitimate result of eating six buns, half a cocoa-nut, three doughnuts, two ices, an apple, and a pound of cherries, and washing the lot down with tea. But Mr. Downing saw in his attack the beginnings of some deadly scourge which would sweep through and decimate the house. He had despatched Adair for the doctor, and, after spending a few minutes prowling restlessly about his room, was now standing at his front gate, waiting for Adair’s return.

It came about, therefore, that Mike, sprinting lightly in the direction of home and safety, had his already shaken nerves further maltreated by being hailed, at a range of about two yards, with a cry of “Is that you, Adair?” The next moment Mr. Downing emerged from his gate.

Mike stood not upon the order of his going. He was off like an arrow—a flying figure of Guilt. Mr. Downing, after the first surprise, seemed to grasp the situation. Ejaculating at intervals the words, “Who is that? Stop! Who is that? Stop!” he dashed after the much-enduring Wrykynian at an extremely creditable rate of speed. Mr. Downing was by way of being a sprinter. He had won handicap events at College sports at Oxford, and, if Mike had not got such a good start, the race might have been over in the first fifty yards. As it was, that victim of Fate, going well, kept ahead. At the entrance to the school grounds he led by a dozen yards. The procession passed into the field, Mike heading as before for the pavilion.

As they raced across the soft turf, an idea occurred to Mike which he was accustomed in after years to attribute to genius, the one flash of it which had ever illumined his life.

It was this.

One of Mr. Downing’s first acts, on starting the Fire Brigade at Sedleigh, had been to institute an alarm bell. It had been rubbed into the school officially—in speeches from the daïs—by the headmaster, and unofficially—in earnest private conversations—by Mr. Downing, that at the sound of this bell, at whatever hour of day or night, every member of the school must leave his house in the quickest possible way, and make for the open. The bell might mean that the school was on fire, or it might mean that one of the houses was on fire. In any case, the school had its orders—to get out into the open at once.

Nor must it be supposed that the school was without practice at this feat. Every now and then a notice would be found posted up on the board to the effect that there would be fire drill during the dinner hour that day. Sometimes the performance was bright and interesting, as on the occasion when Mr. Downing, marshalling the brigade at his front gate, had said, “My house is supposed to be on fire. Now let’s do a record!” which the Brigade, headed by Stone and Robinson, obligingly did. They fastened the hose to the hydrant, smashed a window on the ground floor (Mr. Downing having retired for a moment to talk with the headmaster), and poured a stream of water into the room. When Mr. Downing was at liberty to turn his attention to the matter, he found that the room selected was his private study, most of the light furniture of which was floating on a miniature lake. That episode had rather discouraged his passion for realism, and fire drill since then had taken the form, for the most part, of “practising escaping.” This was done by means of canvas shoots, kept in the dormitories. At the sound of the bell the prefect of the dormitory would heave one end of the shoot out of window, the other end being fastened to the sill. He would then go down it himself, using his elbows as a brake. Then the second man would follow his example, and these two, standing below, would hold the end of the shoot so that the rest of the dormitory could fly rapidly down it without injury, except to their digestions.

After the first novelty of the thing had worn off, the school had taken a rooted dislike to fire drill. It was a matter for self-congratulation among them that Mr. Downing had never been able to induce the head-master to allow the alarm bell to be sounded for fire drill at night. The head-master, a man who had his views on the amount of sleep necessary for the growing boy, had drawn the line at night operations. “Sufficient unto the day” had been the gist of his reply. If the alarm bell were to ring at night when there was no fire, the school might mistake a genuine alarm of fire for a bogus one, and refuse to hurry themselves.

So Mr. Downing had had to be content with day drill.

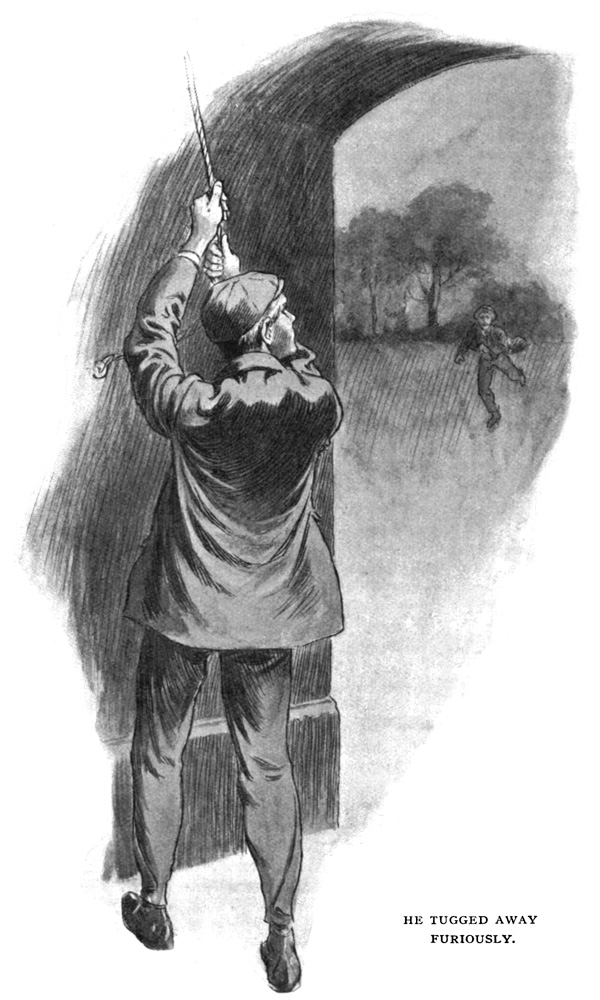

The alarm bell hung in the archway leading into the school grounds. The end of the rope, when not in use, was fastened to a hook half way up the wall.

Mike, as he raced over the cricket field, made up his mind in a flash that his only chance of getting out of this tangle was to shake his pursuer off for a space of time long enough to enable him to get to the rope and tug it. Then the school would come out. He would mix with them, and in the subsequent confusion get back to bed unnoticed.

The task was easier than it would have seemed at the beginning of the chase. Mr. Downing, owing to the two facts that he was not in the strictest training, and that it is only an Alfred Shrubb who can run for any length of time at top speed shouting “Who is that? Stop! Who is that? Stop!” was beginning to feel distressed. There were bellows to mend in the Downing camp. Mike perceived this, and forced the pace. He rounded the pavilion ten yards to the good. Then, heading for the gate, he put all he knew into one last sprint. Mr. Downing was not equal to the effort. He worked gamely for a few strides, then fell behind. When Mike reached the gate, a good forty yards separated them.

As far as Mike could judge—he was not in a condition to make nice calculations—he had about four seconds in which to get busy with that bell rope.

Probably nobody has ever crammed more energetic work into four seconds than he did then.

The night was as still as only an English summer night can be, and the first clang of the clapper sounded like a million iron girders falling from a height on to a sheet of tin. He tugged away furiously, with an eye on the now rapidly advancing and loudly shouting figure of the housemaster.

And from the darkened house beyond there came a gradually swelling hum, as if a vast hive of bees had been disturbed.

The school was awake.

CHAPTER XVII.

the decoration of sammy.

MITH leaned against the mantelpiece

in the senior day-room at Outwood’s—since

Mike’s innings against Downing’s the Lost

Lambs had been received as brothers by that centre

of disorder, so that even Spiller was compelled to

look on the hatchet as buried—and gave his

views on the events of the preceding night, or, rather,

of that morning, for it was nearer one than twelve

when peace had once more fallen on the school.

MITH leaned against the mantelpiece

in the senior day-room at Outwood’s—since

Mike’s innings against Downing’s the Lost

Lambs had been received as brothers by that centre

of disorder, so that even Spiller was compelled to

look on the hatchet as buried—and gave his

views on the events of the preceding night, or, rather,

of that morning, for it was nearer one than twelve

when peace had once more fallen on the school.

“Nothing that happens in this luny-bin,” said Psmith, “has power to surprise me now. There was a time when I might have thought it a little unusual to have to leave the house through a canvas shoot at one o’clock in the morning, but I suppose it’s quite the regular thing here. Old school tradition, &c. Men leave the school, and find that they’ve got so accustomed to jumping out of window that they look on it as a sort of affectation to go out by the door. I suppose none of you merchants can give me any idea when the next knockabout entertainment of this kind is likely to take place?”

“I wonder who rang that bell!” said Stone. “Jolly sporting idea.”

“I believe it was Downing himself. If it was, I hope he’s satisfied.”

Jellicoe, who was appearing in society supported by a stick, looked meaningly at Mike, and giggled, receiving in answer a stony stare. Mike had informed Jellicoe of the details of his interview with Mr. Barley at the “White Boar,” and Jellicoe, after a momentary splutter of wrath against the practical joker, was now in a particularly light-hearted mood. He hobbled about, giggling at nothing and at peace with all the world.

“It was a stirring scene,” said Psmith. “The agility with which Comrade Jellicoe boosted himself down the shoot was a triumph of mind over matter. He seemed to forget his ankle. It was the nearest thing to a Boneless Acrobatic Wonder that I have ever seen.”

“I was in a beastly funk, I can tell you.”

Stone gurgled.

“So was I,” he said, “for a bit. Then, when I saw that it was all a rag, I began to look about for ways of doing the thing really well. I emptied about six jugs of water on a gang of kids under my window.”

“I rushed into Downing’s, and ragged some of the beds,” said Robinson.

“It was an invigorating time,” said Psmith. “A sort of pageant. I was particularly struck with the way some of the bright lads caught hold of the idea. There was no skimping. Some of the kids, to my certain knowledge, went down the shoot a dozen times. There’s nothing like doing a thing thoroughly. I saw them come down, rush upstairs, and be saved again, time after time. The thing became chronic with them. I should say Comrade Downing ought to be satisfied with the high state of efficiency to which he has brought us. At any rate, I hope——”

There was a sound of hurried footsteps outside the door, and Sharpe, a member of the senior day-room, burst excitedly in. He seemed amused.

“I say, have you chaps seen Sammy?”

“Seen who?” said Stone. “Sammy? Why?”

“You’ll know in a second. He’s just outside. Here, Sammy, Sammy, Sammy! Sam! Sam!”

A bark and a patter of feet outside.

“Come on, Sammy. Good dog.”

There was a moment’s silence. Then a great yell of laughter burst forth. Even Psmith’s massive calm was shattered. As for Jellicoe, he sobbed in a corner.

Sammy’s beautiful white coat was almost entirely concealed by a thick covering of bright red paint. His head, with the exception of the ears, was untouched, and his serious, friendly eyes seemed to emphasise the weirdness of his appearance. He stood in the doorway, barking and wagging his tail, plainly puzzled at his reception. He was a popular dog, and was always well received when he visited any of the houses, but he had never before met with enthusiasm like this.

“Good old Sammy!”

“What on earth’s been happening to him?”

“Who did it?”

Sharpe, the introducer, had no views on the matter.

“I found him outside Downing’s, with a crowd round him. Everybody seems to have seen him. I wonder who on earth has gone and mucked him up like that!”

Mike was the first to show any sympathy for the maltreated animal.

“Poor old Sammy,” he said, kneeling on the floor beside the victim, and scratching him under the ear. “What a beastly shame! It’ll take hours to wash all that off him, and he’ll hate it.”

“It seems to me,” said Psmith, regarding Sammy dispassionately through his eyeglass, “that it’s not a case for mere washing. They’ll either have to skin him bodily, or leave the thing to time. Time, the Great Healer. In a year or two he’ll fade to a delicate pink. I don’t see why you shouldn’t have a pink bull-terrier. It would lend a touch of distinction to the place. Crowds would come in excursion trains to see him. By charging a small fee you might make him self-supporting. I think I’ll suggest it to Comrade Downing.”

“There’ll be a row about this,” said Stone.

“Rows are rather sport when you’re not mixed up in them,” said Robinson, philosophically. “There’ll be another if we don’t start off for chapel soon. It’s a quarter to.”

There was a general move. Mike was the last to leave the room. As he was going, Jellicoe stopped him. Jellicoe was staying in that Sunday, owing to his ankle.

“I say,” said Jellicoe, “I just wanted to thank you again about that——”

“Oh, that’s all right.”

“No, but it really was awfully decent of you. You might have got into a frightful row. Were you nearly caught?”

“Jolly nearly.”

“It was you who rang the bell, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, it was. But for goodness sake don’t go gassing about it, or somebody will get to hear who oughtn’t to, and I shall be sacked.”

“All right. But, I say, you are a chap!”

“What’s the matter now?”

“I mean about Sammy, you know. It’s a jolly good score off old Downing. He’ll be frightfully sick.”

“Sammy!” cried Mike. “My good man, you don’t think I did that, do you? What absolute rot! I never touched the poor brute.”

“Oh, all right,” said Jellicoe. “But I wasn’t going to tell any one, of course.”

“What do you mean?”

“You are a chap!” giggled Jellicoe.

Mike walked to chapel rather thoughtfully.

CHAPTER XVIII.

mr. downing on the scent.

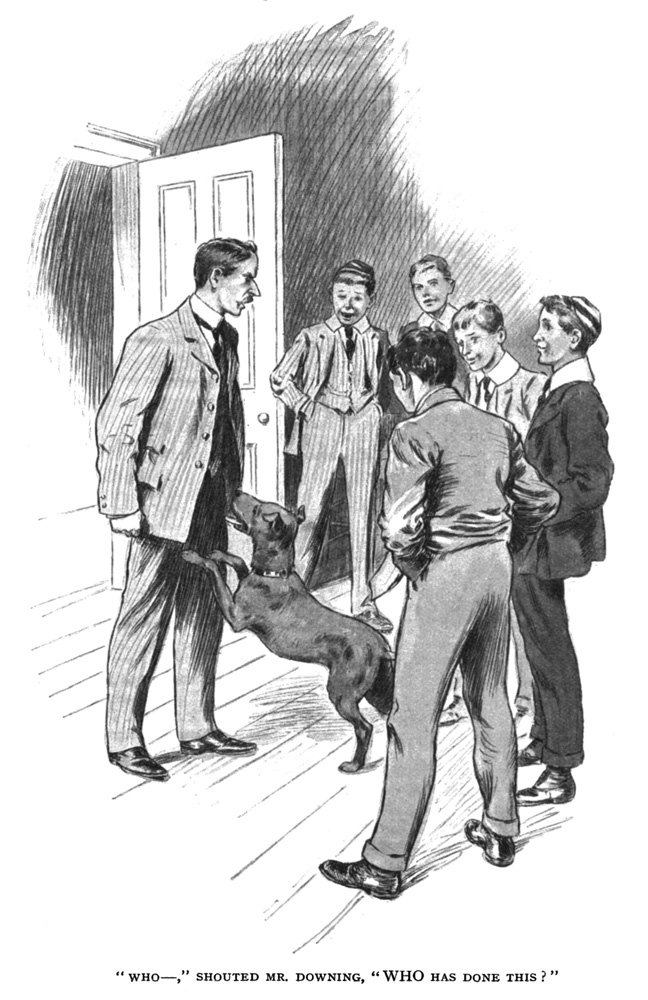

HERE was just one moment, the moment

in which, on going down to the junior day-room of

his house to quell an unseemly disturbance, he was

boisterously greeted by a vermilion bull terrier, when

Mr. Downing was seized with a hideous fear lest he

had lost his senses. Glaring down at the crimson

animal that was pawing at his knees, he clutched at

his reason for one second as a drowning man clutches

at a lifebelt.

HERE was just one moment, the moment

in which, on going down to the junior day-room of

his house to quell an unseemly disturbance, he was

boisterously greeted by a vermilion bull terrier, when

Mr. Downing was seized with a hideous fear lest he

had lost his senses. Glaring down at the crimson

animal that was pawing at his knees, he clutched at

his reason for one second as a drowning man clutches

at a lifebelt.

Then the happy laughter of the young onlookers reassured him.

“Who——” he shouted, “WHO has done this?”

“Please, sir, we don’t know,” shrilled the chorus.

“Please, sir, he came in like that.”

“Please, sir, we were sitting here when he suddenly ran in, all red.”

A voice from the crowd: “Look at old Sammy!”

The situation was impossible. There was nothing to be done. He could not find out by verbal inquiry who had painted the dog. The possibility of Sammy being painted red during the night had never occurred to Mr. Downing, and now that the thing had happened he had no scheme of action. As Psmith would have said, he had confused the unusual with the impossible, and the result was that he was taken by surprise.

While he was pondering on this the situation was rendered still more difficult by Sammy, who, taking advantage of the door being open, escaped and rushed into the road, thus publishing his condition to all and sundry. You can hush up a painted dog while it confines itself to your own premises, but once it has mixed with the great public this becomes out of the question. Sammy’s state advanced from a private trouble into a row. Mr. Downing’s next move was in the same direction that Sammy had taken, only, instead of running about the road, he went straight to the head-master.

The Head, who had had to leave his house in the small hours in his pyjamas and a dressing-gown, was not in the best of tempers. He had a cold in the head, and also a rooted conviction that Mr. Downing, in spite of his strict orders, had rung the bell himself on the previous night in order to test the efficiency of the school in saving themselves in the event of fire. He received the housemaster frostily, but thawed as the latter related the events which had led up to the ringing of the bell.

“Dear me!” he said, deeply interested. “One of the boys at the school, you think?”

“I am certain of it,” said Mr. Downing.

“Was he wearing a school cap?”

“He was bare-headed. A boy who breaks out of his house at night would hardly run the risk of wearing a distinguishing cap.”

“No, no, I suppose not. A big boy, you say?”

“Very big.”

“You did not see his face?”

“It was dark and he never looked back—he was in front of me all the time.”

“Dear me!”

“There is another matter——”

“Yes?”

“This boy, whoever he was, had done something before he rang the bell—he had painted my dog Sampson red.”

The head-master’s eyes protruded from their sockets. “He—he—what, Mr. Downing?”

“He painted my dog red—bright red.” Mr. Downing was too angry to see anything humorous in the incident. Since the previous night he had been wounded in his tenderest feelings. His Fire Brigade system had been most shamefully abused by being turned into a mere instrument in the hands of a malefactor for escaping justice, and his dog had been held up to ridicule to all the world. He did not want to smile, he wanted revenge.

The head-master, on the other hand, did want to smile. It was not his dog, he could look on the affair with an unbiassed eye, and to him there was something ludicrous in a white dog suddenly appearing as a red dog.

“It is a scandalous thing!” said Mr. Downing.

“Quite so! Quite so!” said the head-master hastily. “I shall punish the boy who did it most severely. I will speak to the school in the Hall after chapel.”

Which he did, but without result. A cordial invitation to the criminal to come forward and be executed was received in wooden silence by the school, with the exception of Johnson III., of Outwood’s, who, suddenly reminded of Sammy’s appearance by the head-master’s words, broke into a wild screech of laughter, and was instantly awarded two hundred lines.

The school filed out of the Hall to their various lunches, and Mr. Downing was left with the conviction that, if he wanted the criminal discovered, he would have to discover him for himself.

The great thing in affairs of this kind is to get a good start, and Fate, feeling perhaps that it had been a little hard upon Mr. Downing, gave him a most magnificent start. Instead of having to hunt for a needle in a haystack, he found himself in a moment in the position of being set to find it in a mere truss of straw.

It was Mr. Outwood who helped him. Sergeant Collard had waylaid the archæological expert on his way to chapel, and informed him that at close on twelve the night before he had observed a youth, unidentified, attempting to get into his house via the water-pipe. Mr. Outwood, whose thoughts were occupied with apses and plinths, not to mention cromlechs, at the time, thanked the sergeant with absent-minded politeness and passed on. Later he remembered the fact à propos of some reflections on the subject of burglars in mediæval England, and passed it on to Mr. Downing as they walked back to lunch.

“Then the boy was in your house!” exclaimed Mr. Downing.

“Not actually in, as far as I understand. I gather from the Sergeant that he interrupted him before——”

“I mean he must have been one of the boys in your house.”

“But what was he doing out at that hour?”

“He had broken out.”

“Impossible, I think. Oh yes, quite impossible! I went round the dormitories as usual at eleven o’clock last night, and all the boys were asleep—all of them.”

Mr. Downing was not listening. He was in a state of suppressed excitement and exultation which made it hard for him to attend to his colleague’s slow utterances. He had a clue! Now that the search had narrowed itself down to Outwood’s house, the rest was comparatively easy. Perhaps Sergeant Collard had actually recognised the boy. On reflection he dismissed this as unlikely, for the sergeant would scarcely have kept a thing like that to himself; but he might very well have seen more of him than he, Downing, had seen. It was only with an effort that he could keep himself from rushing to the sergeant then and there, and leaving the house lunch to look after itself. He resolved to go the moment that meal was at an end.

Sunday lunch at a public school house is probably one of the longest functions in existence. It drags its slow length along like a languid snake, but it finishes in time. In due course Mr. Downing, after sitting still and eyeing with acute dislike everybody who asked for a second helping, found himself at liberty.

Regardless of the claims of digestion, he rushed forth on the trail.

Sergeant Collard lived with his wife and a family of unknown dimensions in the lodge at the school front gate. Dinner was just over when Mr. Downing arrived, as a blind man could have told.

The sergeant received his visitor with dignity, ejecting the family, who were torpid after roast beef and resented having to move, in order to ensure privacy.

Having requested his host to smoke, which the latter was about to do unasked, Mr. Downing stated his case.

“Mr. Outwood,” he said, “tells me that last night, sergeant, you saw a boy endeavouring to enter his house.”

The sergeant blew a cloud of smoke. “Oo-oo-oo, yer,” he said; “I did, sir—spotted ’im, I did. Feeflee good at spottin’, I am, sir. Dook of Connaught, he used to say, ‘ ’Ere comes Sergeant Collard,’ he used to say, ‘ ’e’s feeflee good at spottin’.’ ”

“What did you do?”

“Do? Oo-oo-oo! I shouts ‘Oo-oo-oo yer, yer young monkey, what yer doin’ there?’ ”

“Yes?”

“But ’e was off in a flash, and I doubles after ’im prompt.”

“But you didn’t catch him?”

“No, sir,” admitted the sergeant reluctantly.

“Did you catch sight of his face, sergeant?”

“No, sir, ’e was doublin’ away in the opposite direction.”

“Did you notice anything at all about his appearance?”

“ ’E was a long young chap, sir, with a pair of legs on him—feeflee fast ’e run, sir. Oo-oo-oo, feeflee!”

“You noticed nothing else?”

“ ’E wasn’t wearing no cap of any sort, sir.”

“Ah!”

“Bare-’eaded, sir,” added the sergeant, rubbing the point in.

“It was undoubtedly the same boy, undoubtedly! I wish you could have caught a glimpse of his face, sergeant.”

“So do I, sir.”

“You would not be able to recognise him again if you saw him, you think?”

“Oo-oo-oo! Wouldn’t go so far as to say that, sir, ’cos yer see, I’m feeflee good at spottin’, but it was a dark night.”

Mr. Downing rose to go.

“Well,” he said, “the search is now considerably narrowed down, considerably! It is certain that the boy was one of the boys in Mr. Outwood’s house.”

“Young monkeys!” interjected the sergeant helpfully.

“Good-afternoon, sergeant.”

“Good-afternoon to you, sir.”

“Pray do not move, sergeant.”

The sergeant had not shown the slightest inclination of doing anything of the kind.

“I will find my way out. Very hot to-day, is it not?”

“Feeflee warm, sir; weather’s goin’ to break—workin’ up for thunder.”

“I hope not. The school plays the M.C.C. on Wednesday, and it would be a pity if rain were to spoil our first fixture with them. Good afternoon.”

And Mr. Downing went out into the baking sunlight, while Sergeant Collard, having requested Mrs. Collard to take the children out for a walk at once, and furthermore to give young Ernie a clip side of the ’ead, if he persisted in making so much noise, put a handkerchief over his face, rested his feet on the table, and slept the sleep of the just.

CHAPTER XIX.

the sleuth-hound.

OR the Doctor Watsons of this world,

as opposed to the Sherlock Holmeses, success in the

province of detective work must always be, to a very

large extent, the result of luck. Sherlock Holmes

can extract a clue from a wisp of straw or a flake

of cigar-ash. But Doctor Watson has got to have

it taken out for him, and dusted, and exhibited clearly,

with a label attached.

OR the Doctor Watsons of this world,

as opposed to the Sherlock Holmeses, success in the

province of detective work must always be, to a very

large extent, the result of luck. Sherlock Holmes

can extract a clue from a wisp of straw or a flake

of cigar-ash. But Doctor Watson has got to have

it taken out for him, and dusted, and exhibited clearly,

with a label attached.

The average man is a Doctor Watson. We are wont to scoff in a patronising manner at that humble follower of the great investigator, but, as a matter of fact, we should have been just as dull ourselves. We should not even have risen to the modest level of a Scotland Yard Bungler. We should simply have hung around, saying: “My dear Holmes, how——?” and all the rest of it, just as the downtrodden medico did.

It is not often that the ordinary person has any need to see what he can do in the way of detection. He gets along very comfortably in the humdrum round of life without having to measure footprints and smile quiet, tight-lipped smiles. But if ever the emergency does arise, he thinks naturally of Sherlock Holmes, and his methods.

Mr. Downing had read all the Holmes stories with great attention, and had thought many times what an incompetent ass Doctor Watson was; but, now that he had started to handle his own first case, he was compelled to admit that there was a good deal to be said in extenuation of Watson’s inability to unravel tangles. It certainly was uncommonly hard, he thought, as he paced the cricket field after leaving Sergeant Collard, to detect anybody, unless you knew who had really done the crime. As he brooded over the case in hand, his sympathy for Dr. Watson increased with every minute, and he began to feel a certain resentment against Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It was all very well for Sir Arthur to be so shrewd and infallible about tracing a mystery to its source, but he knew perfectly well who had done the thing before he started!

Now that he began really to look into this matter of the alarm bell and the painting of Sammy, the conviction was creeping over him that the problem was more difficult than a casual observer might imagine. He had got as far as finding that his quarry of the previous night was a boy in Mr. Outwood’s house, but how was he to get any farther? That was the thing. There were, of course, only a limited number of boys in Mr. Outwood’s house as tall as the one he had pursued; but even if there had been only one other, it would have complicated matters. If you go to a boy and say, “Either you or Jones were out of your house last night at twelve o’clock,” the boy does not reply, “Sir, I cannot tell a lie—I was out of my house last night at twelve o’clock.” He simply assumes the animated expression of a stuffed fish, and leaves the next move to you. It is practically Stale Mate.

All these things passed through Mr. Downing’s mind as he walked up and down the cricket field that afternoon.

What he wanted was a clue. But it is so hard for the novice to tell what is a clue and what isn’t. Probably, if he only knew, there were clues lying all over the place, shouting to him to pick them up.

What with the oppressive heat of the day and the fatigue of hard thinking, Mr. Downing was working up for a brain-storm, when Fate once more intervened, this time in the shape of Riglett, a junior member of his house.

Riglett slunk up in the shamefaced way peculiar to some boys, even when they have done nothing wrong, and, having capped Mr. Downing with the air of one who has been caught in the act of doing something particularly shady, requested that he might be allowed to fetch his bicycle from the shed.

“Your bicycle?” snapped Mr. Downing. Much thinking had made him irritable. “What do you want with your bicycle?”

Riglett shuffled, stood first on his left foot, then on his right, blushed, and finally remarked, as if it were not so much a sound reason as a sort of feeble excuse for the low and blackguardly fact that he wanted his bicycle, that he had got leave for tea that afternoon.

Then Mr. Downing remembered. Riglett had an aunt resident about three miles from the school, whom he was accustomed to visit occasionally on Sunday afternoons during the term.

He felt for his bunch of keys, and made his way to the shed, Riglett shambling behind at an interval of two yards.

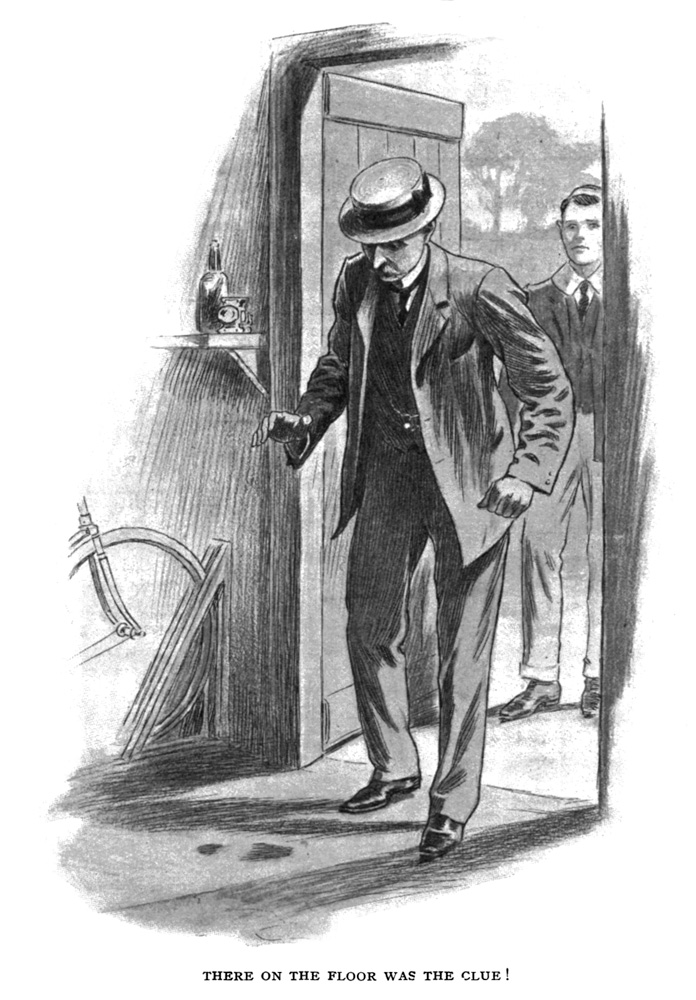

Mr. Downing unlocked the door, and there on the floor was the Clue!

A clue that even Dr. Watson could not have overlooked.

Mr. Downing saw it, but did not immediately recognise it for what it was. What he saw at first was not a Clue, but just a mess. He had a tidy soul and abhorred messes. And this was a particularly messy mess. The greater part of the flooring in the neighbourhood of the door was a sea of red paint. The tin from which it had flowed was lying on its side in the middle of the shed. The air was full of the pungent scent.

“Pah!” said Mr. Downing.

Then suddenly, beneath the disguise of the mess, he saw the clue. A footmark! No less. A crimson footmark on the grey concrete!

Riglett, who had been waiting patiently two yards away, now coughed plaintively. The sound recalled Mr. Downing to mundane matters.

“Get your bicycle, Riglett,” he said, “and be careful where you tread. Somebody has upset a pot of paint on the floor.”

Riglett, walking delicately through dry places, extracted his bicycle from the rack, and presently departed to gladden the heart of his aunt, leaving Mr. Downing, his brain fizzing with the enthusiasm of the detective, to lock the door and resume his perambulation of the cricket field.

Give Dr. Watson a fair start, and he is a demon at the game. Mr. Downing’s brain was now working with a rapidity and clearness which a professional sleuth might have envied.

Paint. Red paint. Obviously the same paint with which Sammy had been decorated. A foot-mark. Whose foot-mark? Plainly that of the criminal who had done the deed of decoration.

Yoicks!

There were two things, however, to be considered. Your careful detective must consider everything. In the first place, the paint might have been upset by the ground-man. It was the ground-man’s paint. He had been giving a fresh coating to the wood-work in front of the pavilion scoring-box at the conclusion of yesterday’s match. (A labour of love which was the direct outcome of the enthusiasm for work which Adair had instilled into him.) In that case the foot-mark might be his.

Note one: Interview the ground-man on this point.

In the second place Adair might have upset the tin and trodden in its contents when he went to get his bicycle in order to fetch the doctor for the suffering MacPhee. This was the more probable of the two contingencies, for it would have been dark in the shed when Adair went into it.

Note two: Interview Adair as to whether he found, on returning to the house, that there was paint on his boots.

Things were moving.

He resolved to take Adair first. He could get the ground-man’s address from him.

Passing by the trees under whose shade Mike and Psmith and Dunster had watched the match on the previous day, he came upon the head of his house in a deck-chair reading a book. A summer Sunday afternoon is the time for reading in deck-chairs.

“Oh, Adair,” he said. “No, don’t get up. I merely wished to ask you if you found any paint on your boots when you returned to the house last night?”

“Paint, sir?” Adair was plainly puzzled. His book had been interesting, and had driven the Sammy incident out of his head.

“I see somebody has spilt some paint on the floor of the bicycle shed. You did not do that, I suppose, when you went to fetch your bicycle?”

“No, sir.”

“It is spilt all over the floor. I wondered whether you had happened to tread in it. But you say you found no paint on your boots this morning?”

“No, sir, my bicycle is always quite near the door of the shed. I didn’t go into the shed at all.”

“I see. Quite so. Thank you, Adair. Oh, by the way, Adair, where does Markby live?”

“I forget the name of his cottage, sir, but I could show you in a second. It’s one of those cottages just past the school gates, on the right as you turn out into the road. There are three in a row. His is the first you come to. There’s a barn just before you get to them.”

“Thank you. I shall be able to find them. I should like to speak to Markby for a moment on a small matter.”

A sharp walk took him to the cottages Adair had mentioned. He rapped at the door of the first, and the ground-man came out in his shirt-sleeves, blinking as if he had just woke up, as was indeed the case.

“Oh, Markby!”

“Sir?”

“You remember that you were painting the scoring-box in the pavilion last night after the match?”

“Yes, sir. It wanted a lick of paint bad. The young gentlemen will scramble about and get through the window. Makes it look shabby, sir. So I thought I’d better give it a coating so as to look ship-shape when the Marylebone come down.”

“Just so. An excellent idea. Tell me, Markby, what did you do with the pot of paint when you had finished?”

“Put it in the bicycle shed, sir.”

“On the floor?”

“On the floor, sir? No. On the shelf at the far end, with the can of whitening what I use for marking out the wickets, sir.”

“Of course, yes. Quite so. Just as I thought.”

“Do you want it, sir?”

“No, thank you, Markby, no, thank you. The fact is, somebody who had no business to do so has moved the pot of paint from the shelf to the floor, with the result that it has been kicked over, and spilt. You had better get some more to-morrow. Thank you, Markby. That is all I wished to know.”

Mr. Downing walked back to the school thoroughly excited. He was hot on the scent now. The only other possible theories had been tested and successfully exploded. The thing had become simple to a degree. All he had to do was to go to Mr. Outwood’s house—the idea of searching a fellow-master’s house did not appear to him at all a delicate task; somehow one grew unconsciously to feel that Mr. Outwood did not really exist as a man capable of resenting liberties—find the paint-splashed boot, ascertain its owner, and denounce him to the head-master. Picture, Blue Fire and “God Save the King” by the full strength of the company. There could be no doubt that a paint-splashed boot must be in Mr. Outwood’s house somewhere. A boy cannot tread in a pool of paint without showing some signs of having done so. It was Sunday, too, so that the boot would not yet have been cleaned. Yoicks! Also Tally-ho! This really was beginning to be something like business.

Regardless of the heat, the sleuth-hound hurried across to Outwood’s as fast as he could walk.

CHAPTER XX.

a check.

HE only two members of the house

not out in the grounds when he arrived were Mike and

Psmith. They were standing on the gravel drive

in front of the boys’ entrance. Mike had

a deck-chair in one hand and a book in the other.

Psmith—for even the greatest minds will

sometimes unbend—was playing diabolo.

That is to say, he was trying without success to raise

the spool from the ground.

HE only two members of the house

not out in the grounds when he arrived were Mike and

Psmith. They were standing on the gravel drive

in front of the boys’ entrance. Mike had

a deck-chair in one hand and a book in the other.

Psmith—for even the greatest minds will

sometimes unbend—was playing diabolo.

That is to say, he was trying without success to raise

the spool from the ground.

“There’s a kid in France,” said Mike disparagingly, as the bobbin rolled off the string for the fourth time, “who can do it three thousand seven hundred and something times.”

Psmith smoothed a crease out of his waistcoat and tried again. He had just succeeded in getting the thing to spin when Mr. Downing arrived. The sound of his footsteps disturbed Psmith and brought the effort to nothing.

“Enough of this spoolery,” said he, flinging the sticks through the open window of the senior day-room. “I was an ass ever to try it. The philosophical mind needs complete repose in its hours of leisure. Hullo!”

He stared after the sleuth-hound, who had just entered the house.

“What the dickens,” said Mike, “does he mean by bargeing in as if he’d bought the place?”

“Comrade Downing looks pleased with himself. What brings him round in this direction, I wonder! Still, no matter. The few articles which he may sneak from our study are of inconsiderable value. He is welcome to them. Do you feel inclined to wait awhile till I have fetched a chair and book?”

“I’ll be going on. I shall be under the trees at the far end of the ground.”

“ ’Tis well. I will be with you in about two ticks.”

Mike walked on towards the field, and Psmith, strolling upstairs to fetch his novel, found Mr. Downing standing in the passage with the air of one who has lost his bearings.

“A warm afternoon, sir,” murmured Psmith courteously, as he passed.

“Er—Smith!”

“Sir?”

“I—er—wish to go round the dormitories.”

It was Psmith’s guiding rule in life never to be surprised at anything, so he merely inclined his head gracefully, and said nothing.

“I should be glad if you would fetch the keys and show me where the rooms are.”

“With acute pleasure, sir,” said Psmith. “Or shall I fetch Mr. Outwood, sir?”

“Do as I tell you, Smith,” snapped Mr. Downing.

Psmith said no more, but went down to the matron’s room. The matron being out, he abstracted the bunch of keys from her table and rejoined the master.

“Shall I lead the way, sir?” he asked.

Mr. Downing nodded.

“Here, sir,” said Psmith, opening a door, “we have Barnes’ dormitory. An airy room, constructed on the soundest hygienic principles. Each boy, I understand, has quite a considerable number of cubic feet of air all to himself. It is Mr. Outwood’s boast that no boy has ever asked for a cubic foot of air in vain. He argues justly——”

He broke off abruptly and began to watch the other’s manœuvres in silence. Mr. Downing was peering rapidly beneath each bed in turn.

“Are you looking for Barnes, sir?” inquired Psmith politely. “I think he’s out in the field.”

Mr. Downing rose, having examined the last bed, crimson in the face with the exercise.

“Show me the next dormitory, Smith,” he said, panting slightly.

“This,” said Psmith, opening the next door and sinking his voice to an awed whisper, “is where I sleep!”

Mr. Downing glanced swiftly beneath the three beds.

“Excuse me, sir,” said Psmith, “but are we chasing anything?”

“Be good enough, Smith,” said Mr. Downing with asperity, “to keep your remarks to yourself.”

“I was only wondering, sir. Shall I show you the next in order?”

“Certainly.”

They moved on up the passage.

Drawing blank at the last dormitory, Mr. Downing paused, baffled. Psmith waited patiently by. An idea struck the master.

“The studies, Smith,” he cried.

“Aha!” said Psmith. “I beg your pardon, sir. The observation escaped me unawares. The frenzy of the chase is beginning to enter into my blood. Here we have——”

Mr. Downing stopped short.

“Is this impertinence studied, Smith?”

“Ferguson’s study, sir? No, sir. That’s further down the passage. This is Barnes’.”

Mr. Downing looked at him closely. Psmith’s face was wooden in its gravity. The master snorted suspiciously, then moved on.

“Whose is this?” he asked, rapping a door.

“This, sir, is mine and Jackson’s.”

“What! Have you a study? You are low down in the school for it.”

“I think, sir, that Mr. Outwood gave it us rather as a testimonial to our general worth than to our proficiency in school-work.”

Mr. Downing raked the room with a keen eye. The absence of bars from the window attracted his attention.

“Have you no bars to your windows here, such as there are in my house?”

“There appears to be no bar, sir,” said Psmith, putting up his eyeglass.

Mr. Downing was leaning out of the window.

“A lovely view, is it not, sir?” said Psmith. “The trees, the field, the distant hills——”

Mr. Downing suddenly started. His eye had been caught by the water-pipe at the side of the window. The boy whom Sergeant Collard had seen climbing the pipe must have been making for this study.

He spun round and met Psmith’s blandly inquiring gaze. He looked at Psmith carefully for a moment. No. The boy he had chased last night had not been Psmith. That exquisite’s figure and general appearance were unmistakable, even in the dusk.

“Whom did you say you shared this study with, Smith?”

“Jackson, sir. The cricketer.”

“Never mind about his cricket, Smith,” said Mr. Downing with irritation.

“No, sir.”

“He is the only other occupant of the room?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Nobody else comes into it?”

“If they do, they go out extremely quickly, sir.”

“Ah! Thank you, Smith.”

“Not at all, sir.”

Mr. Downing pondered. Jackson! The boy bore him a grudge. The boy was precisely the sort of boy to revenge himself by painting the dog Sammy. And, gadzooks! The boy whom he had pursued last night had been just about Jackson’s size and build!

Mr. Downing was as firmly convinced at that moment that Mike’s had been the hand to wield the paint-brush as he had ever been of anything in his life.

“Smith!” he said excitedly.

“On the spot, sir,” said Psmith affably.

“Where are Jackson’s boots?”

There are moments when the giddy excitement of being right on the trail causes the amateur (or Watsonian) detective to be incautious. Such a moment came to Mr. Downing then. If he had been wise, he would have achieved his object, the getting a glimpse of Mike’s boots, by a devious and snaky route. As it was, he rushed straight on.

“His boots, sir? He has them on. I noticed them as he went out just now.”

“Where is the pair he wore yesterday?”

“Where are the boots of yester-year?” murmured Psmith to himself. “I should say at a venture, sir, that they would be in the basket downstairs. Edmund, our genial knife-and-boot boy, collects them, I believe, at early dawn.”

“Would they have been cleaned yet?”

“If I know Edmund, sir—no.”

“Smith,” said Mr. Downing, trembling with excitement, “go and bring that basket to me here.”

Psmith’s brain was working rapidly as he went downstairs. What exactly was at the back of the sleuth’s mind, prompting these manœuvres, he did not know. But that there was something, and that that something was directed in a hostile manner against Mike, probably in connection with last night’s wild happenings, he was certain. Psmith had noticed, on leaving his bed at the sound of the alarm bell, that he and Jellicoe were alone in the room. That might mean that Mike had gone out through the door when the bell sounded, or it might mean that he had been out all the time. It began to look as if the latter solution were the correct one.

He staggered back with the basket, painfully conscious the while that it was creasing his waistcoat, and dumped it down on the study floor. Mr. Downing stooped eagerly over it. Psmith leaned against the wall, and straightened out the damaged garment.

“We have here, sir,” he said, “a fair selection of our various bootings.”

Mr. Downing looked up.

“You dropped none of the boots on your way up, Smith?”

“Not one, sir. It was a fine performance.”

Mr. Downing uttered a grunt of satisfaction, and bent once more to his task. Boots flew about the room. Mr. Downing knelt on the floor beside the basket, and dug like a terrier at a rat-hole.

At last he made a dive, and, with an exclamation of triumph, rose to his feet. In his hand he held a boot.

“Put those back again, Smith,” he said.

The ex-Etonian, wearing an expression such as a martyr might have worn on being told off for the stake, began to pick up the scattered footgear, whistling softly the tune of “I do all the dirty work,” as he did so.

“That’s the lot, sir,” he said, rising.

“Ah. Now come across with me to the headmaster’s house. Leave the basket here. You can carry it back when you return.”

“Shall I put back that boot, sir?”

“Certainly not. I shall take this with me, of course.”

“Shall I carry it, sir?”

Mr. Downing reflected.

“Yes, Smith,” he said. “I think it would be best.”

It occurred to him that the spectacle of a housemaster wandering abroad on the public highway, carrying a dirty boot, might be a trifle undignified. You never knew whom you might meet on Sunday afternoon.

Psmith took the boot, and doing so, understood what before had puzzled him.

Across the toe of the boot was a broad splash of red paint.

He knew nothing, of course, of the upset tin in the bicycle shed; but when a housemaster’s dog has been painted red in the night, and when, on the following day, the housemaster goes about in search of a paint-splashed boot, one puts two and two together. Psmith looked at the name inside the boot. It was “Brown, boot-maker, Bridgnorth.” Bridgnorth was only a few miles from his own home and Mike’s. Undoubtedly it was Mike’s boot.

“Can you tell me whose boot that is?” asked Mr. Downing.

Psmith looked at it again.

“No, sir. I can’t say the little chap’s familiar to me.”

“Come with me, then.”

Mr. Downing left the room. After a moment Psmith followed him.

The head-master was in his garden. Thither Mr. Downing made his way, the boot-bearing Psmith in close attendance.

The Head listened to the amateur detective’s statement with interest.

“Indeed?” he said, when Mr. Downing had finished.

“Indeed? Dear me! It certainly seems— It is a curiously well-connected thread of evidence. You are certain that there was red paint on this boot you discovered in Mr. Outwood’s house?”

“I have it with me. I brought it on purpose to show to you. Smith!”

“Sir?”

“You have the boot?”

“Ah,” said the headmaster, putting on a pair of pince-nez, “now let me look at— This, you say, is the—? Just so. Just so. Just . . . But, er, Mr. Downing, it may be that I have not examined this boot with sufficient care, but— Can you point out to me exactly where this paint is that you speak of?”

Mr. Downing stood staring at the boot with a wild, fixed stare. Of any suspicion of paint, red or otherwise, it was absolutely and entirely innocent.

(To be continued.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums