The Captain, August 1908

CHAPTER XXI.

the destroyer of evidence.

boot became the centre of attraction,

the cynosure of all eyes. Mr. Downing fixed it

with the piercing stare of one who feels that his

brain is tottering. The headmaster looked at it

with a mildly puzzled expression. Psmith, putting

up his eyeglass, gazed at it with a sort of affectionate

interest, as if he were waiting for it to do a trick

of some kind.

boot became the centre of attraction,

the cynosure of all eyes. Mr. Downing fixed it

with the piercing stare of one who feels that his

brain is tottering. The headmaster looked at it

with a mildly puzzled expression. Psmith, putting

up his eyeglass, gazed at it with a sort of affectionate

interest, as if he were waiting for it to do a trick

of some kind.

Mr. Downing was the first to break the silence.

“There was paint on this boot,” he said vehemently. “I tell you there was a splash of red paint across the toe. Smith will bear me out in this. Smith, you saw the paint on this boot?”

“Paint, sir!”

“What! Do you mean to tell me that you did not see it?”

“No, sir. There was no paint on this boot.”

“This is foolery. I saw it with my own eyes. It was a broad splash right across the toe.”

The headmaster interposed.

“You must have made a mistake, Mr. Downing. There is certainly no trace of paint on this boot. These momentary optical delusions are, I fancy, not uncommon. Any doctor will tell you——”

“I had an aunt, sir,” said Psmith chattily, “who was remarkably subject——”

“It is absurd. I cannot have been mistaken,” said Mr. Downing. “I am positively certain the toe of this boot was red when I found it.”

“It is undoubtedly black now, Mr. Downing.”

“A sort of chameleon boot,” murmured Psmith.

The goaded housemaster turned on him.

“What did you say, Smith?”

“Did I speak, sir?” said Psmith, with the start of one coming suddenly out of a trance.

Mr. Downing looked searchingly at him.

“You had better be careful, Smith.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I strongly suspect you of having something to do with this.”

“Really, Mr. Downing,” said the headmaster, “that is surely improbable. Smith could scarcely have cleaned the boot on his way to my house. On one occasion I inadvertently spilt some paint on a shoe of my own. I can assure you that it does not brush off. It needs a very systematic cleaning before all traces are removed.”

“Exactly, sir,” said Psmith. “My theory, if I may——?”

“Certainly, Smith.”

Psmith bowed courteously and proceeded.

“My theory, sir, is that Mr. Downing was deceived by the light and shade effects on the toe of the boot. The afternoon sun, streaming in through the window, must have shone on the boot in such a manner as to give it a momentary and fictitious aspect of redness. If Mr. Downing recollects, he did not look long at the boot. The picture on the retina of the eye, consequently, had not time to fade. I remember thinking myself, at the moment, that the boot appeared to have a certain reddish tint. The mistake——”

“Bah!” said Mr. Downing shortly.

“Well, really,” said the headmaster, “it seems to me that that is the only explanation that will square with the facts. A boot that is really smeared with red paint does not become black of itself in the course of a few minutes.”

“You are very right, sir,” said Psmith with benevolent approval. “May I go now, sir? I am in the middle of a singularly impressive passage of Cicero’s speech De Senectute.”

“I am sorry that you should leave your preparation till Sunday, Smith. It is a habit of which I altogether disapprove.”

“I am reading it, sir,” said Psmith, with simple dignity, “for pleasure. Shall I take the boot with me, sir?”

“If Mr. Downing does not want it?”

The housemaster passed the fraudulent piece of evidence to Psmith without a word, and the latter, having included both masters in a kindly smile, left the garden.

Pedestrians who had the good fortune to be passing along the road between the housemaster’s house and Mr. Outwood’s at that moment saw what, if they had but known it, was a most unusual sight, the spectacle of Psmith running. Psmith’s usual mode of progression was a dignified walk. He believed in the contemplative style rather than the hustling.

On this occasion, however, reckless of possible injuries to the crease of his trousers, he raced down the road, and turning in at Outwood’s gate, bounded upstairs like a highly trained professional athlete.

On arriving at the study, his first act was to remove a boot from the top of the pile in the basket, place it in the small cupboard under the bookshelf, and lock the cupboard. Then he flung himself into a chair and panted.

“Brain,” he said to himself approvingly, “is what one chiefly needs in matters of this kind. Without brain, where are we? In the soup, every time. The next development will be when Comrade Downing thinks it over, and is struck with the brilliant idea that it’s just possible that the boot he gave me to carry and the boot I did carry were not one boot but two boots. Meanwhile——”

He dragged up another chair for his feet and picked up his novel.

He had not been reading long when there was a footstep in the passage, and Mr. Downing appeared.

The possibility, in fact the probability, of Psmith having substituted another boot for the one with the incriminating splash of paint on it had occurred to him almost immediately on leaving the headmaster’s garden. Psmith and Mike, he reflected, were friends. Psmith’s impulse would be to do all that lay in his power to shield Mike. Feeling aggrieved with himself that he had not thought of this before, he, too, hurried over to Outwood’s.

Mr. Downing was brisk and peremptory.

“I wish to look at these boots again,” he said. Psmith, with a sigh, laid down his novel, and rose to assist him.

“Sit down, Smith,” said the housemaster. “I can manage without your help.”

Psmith sat down again, carefully tucking up the knees of his trousers, and watched him with silent interest through his eyeglass.

The scrutiny irritated Mr. Downing.

“Put that thing away, Smith,” he said.

“That thing, sir?”

“Yes, that ridiculous glass. Put it away.”

“Why, sir?”

“Why! Because I tell you to do so.”

“I guessed that that was the reason, sir,” sighed Psmith, replacing the eyeglass in his waistcoat pocket. He rested his elbows on his knees, and his chin on his hands, and resumed his contemplative inspection of the boot-expert, who, after fidgeting for a few moments, lodged another complaint.

“Don’t sit there staring at me, Smith.”

“I was interested in what you were doing, sir.”

“Never mind. Don’t stare at me in that idiotic way.”

“May I read, sir?” asked Psmith, patiently.

“Yes, read if you like.”

“Thank you, sir.”

Psmith took up his book again, and Mr. Downing, now thoroughly irritated, pursued his investigations in the boot-basket.

He went through it twice, but each time without success. After the second search, he stood up, and looked wildly round the room. He was as certain as he could be of anything that the missing piece of evidence was somewhere in the study. It was no use asking Psmith point-blank where it was, for Psmith’s ability to parry dangerous questions with evasive answers was quite out of the common.

His eye roamed about the room. There was very little cover there, even for so small a fugitive as a number nine boot. The floor could be acquitted, on sight, of harbouring the quarry.

Then he caught sight of the cupboard, and something seemed to tell him that there was the place to look.

“Smith!” he said.

Psmith had been reading placidly all the while.

“Yes, sir?”

“What is in this cupboard?”

“That cupboard, sir?”

“Yes. This cupboard.” Mr. Downing rapped the door irritably.

“Just a few odd trifles, sir. We do not often use it. A ball of string, perhaps. Possibly an old note-book. Nothing of value or interest.”

“Open it.”

“I think you will find that it is locked, sir.”

“Unlock it.”

“But where is the key, sir?”

“Have you not got the key?”

“If the key is not in the lock, sir, you may depend upon it that it will take a long search to find it.”

“Where did you see it last?”

“It was in the lock yesterday morning. Jackson might have taken it.”

“Where is Jackson?”

“Out in the field somewhere, sir.”

Mr. Downing thought for a moment.

“I don’t believe a word of it,” he said shortly. “I have my reasons for thinking that you are deliberately keeping the contents of that cupboard from me. I shall break open the door.”

Psmith got up.

“I’m afraid you mustn’t do that, sir.”

Mr. Downing stared, amazed.

“Are you aware whom you are talking to, Smith?” he inquired acidly.

“Yes, sir. And I know it’s not Mr. Outwood, to whom that cupboard happens to belong. If you wish to break it open, you must get his permission. He is the sole lessee and proprietor of that cupboard. I am only the acting manager.”

Mr. Downing paused. He also reflected. Mr. Outwood in the general rule did not count much in the scheme of things, but possibly there were limits to the treating of him as if he did not exist. To enter his house without his permission and search it to a certain extent was all very well. But when it came to breaking up his furniture, perhaps——!

On the other hand, there was the maddening thought that if he left the study in search of Mr. Outwood, in order to obtain his sanction for the house-breaking work which he proposed to carry through, Smith would be alone in the room. And he knew that, if Smith were left alone in the room, he would instantly remove the boot to some other hiding-place. He thoroughly disbelieved the story of the lost key. He was perfectly convinced that the missing boot was in the cupboard.

He stood chewing these thoughts for a-while. Psmith in the meantime standing in a graceful attitude in front of the cupboard, staring into vacancy.

Then he was seized with a happy idea. Why should he leave the room at all? If he sent Smith, then he himself could wait and make certain that the cupboard was not tampered with.

“Smith,” he said, “go and find Mr. Outwood, and ask him to be good enough to come here for a moment.”

CHAPTER XXII.

mainly about boots.

E quick, Smith,” he

said, as the latter stood looking at him without making

any movement in the direction of the door.

E quick, Smith,” he

said, as the latter stood looking at him without making

any movement in the direction of the door.

“Quick, sir?” said Psmith meditatively, as if he had been asked a conundrum.

“Go and find Mr. Outwood at once.”

Psmith still made no move.

“Do you intend to disobey me, Smith?” Mr. Downing’s voice was steely.

“Yes, sir.”

“What!”

“Yes, sir.”

There was one of those you-could-have-heard-a-pin-drop silences. Psmith was staring reflectively at the ceiling. Mr. Downing was looking as if at any moment he might say, “Thwarted to me face, ha, ha! And by a very stripling!”

It was Psmith, however, who resumed the conversation. His manner was almost too respectful; which made it all the more a pity that what he said did not keep up the standard of docility.

“I take my stand,” he said, “on a technical point. I say to myself, ‘Mr. Downing is a man I admire as a human being and respect as a master. In——’ ”

“This impertinence is doing you no good, Smith.”

Psmith waved a hand deprecatingly.

“If you will let me explain, sir. I was about to say that in any other place but Mr. Outwood’s house, your word would be law. I would fly to do your bidding. If you pressed a button, I would do the rest. But in Mr. Outwood’s house I cannot do anything except what pleases me or what is ordered by Mr. Outwood. I ought to have remembered that before. One cannot,” he continued, as who should say, “Let us be reasonable,” “one cannot, to take a parallel case, imagine the colonel commanding the garrison at a naval station going on board a battleship and ordering the crew to splice the jibboom spanker. It might be an admirable thing for the Empire that the jibboom spanker should be spliced at that particular juncture, but the crew would naturally decline to move in the matter until the order came from the commander of the ship. So in my case. If you will go to Mr. Outwood, and explain to him how matters stand, and come back and say to me, ‘Psmith, Mr. Outwood wishes you to ask him to be good enough to come to this study,’ then I shall be only too glad to go and find him. You see my difficulty, sir?”

“Go and fetch Mr. Outwood, Smith. I shall not tell you again.”

Psmith flicked a speck of dust from his coat-sleeve.

“Very well, Smith.”

“I can assure you, sir, at any rate, that if there is a boot in that cupboard now, there will be a boot there when you return.”

Mr. Downing stalked out of the room.

“But,” added Psmith pensively to himself, as the footsteps died away, “I did not promise that it would be the same boot.”

He took the key from his pocket, unlocked the cupboard, and took out the boot. Then he selected from the basket a particularly battered specimen. Placing this in the cupboard, he re-locked the door.

His next act was to take from the shelf a piece of string. Attaching one end of this to the boot that he had taken from the cupboard, he went to the window. His first act was to fling the cupboard-key out into the bushes. Then he turned to the boot. On a level with the sill the water-pipe, up which Mike had started to climb the night before, was fastened to the wall by an iron band. He tied the other end of the string to this, and let the boot swing free. He noticed with approval, when it had stopped swinging, that it was hidden from above by the window-sill.

He returned to his place at the mantelpiece.

As an after-thought he took another boot from the basket, and thrust it up the chimney. A shower of soot fell into the grate, blackening his hand.

The bathroom was a few yards down the corridor. He went there, and washed off the soot.

When he returned, Mr. Downing was in the study, and with him Mr. Outwood, the latter looking dazed, as if he were not quite equal to the intellectual pressure of the situation.

“Where have you been, Smith?” asked Mr. Downing sharply.

“I have been washing my hands, sir.”

“H’m!” said Mr. Downing suspiciously.

“Yes, I saw Smith go into the bathroom,” said Mr. Outwood. “Smith, I cannot quite understand what it is Mr. Downing wishes me to do.”

“My dear Outwood,” snapped the sleuth, “I thought I had made it perfectly clear. Where is the difficulty?”

“I cannot understand why you should suspect Smith of keeping his boots in a cupboard, and,” added Mr. Outwood, with spirit, catching sight of a Good-Gracious-has-the-man-no-sense look on the other’s face, “why he should not do so if he wishes it.”

“Exactly, sir,” said Psmith, approvingly. “You have touched the spot.”

“If I must explain again, my dear Outwood, will you kindly give me your attention for a moment. Last night a boy broke out of your house, and painted my dog Sampson red.”

“He painted——!” said Mr. Outwood, round-eyed. “Why?”

“I don’t know why. At any rate, he did. During the escapade one of his boots was splashed with the paint. It is that boot which I believe Smith to be concealing in this cupboard. Now, do you understand?”

Mr. Outwood looked amazedly at Smith, and Psmith shook his head sorrowfully at Mr. Outwood. Psmith’s expression said, as plainly as if he had spoken the words, “We must humour him.”

“So with your permission, as Smith declares that he has lost the key, I propose to break open the door of this cupboard. Have you any objection?”

Mr. Outwood started.

“Objection? None at all, my dear fellow, none at all. Let me see, what is it you wish to do?”

“This,” said Mr. Downing shortly.

There was a pair of dumb-bells on the floor, belonging to Mike. He never used them, but they always managed to get themselves packed with the rest of his belongings on the last day of the holidays. Mr. Downing seized one of these, and delivered two rapid blows at the cupboard-door. The wood splintered. A third blow smashed the flimsy lock. The cupboard, with any skeletons it might contain, was open for all to view.

Mr. Downing uttered a cry of triumph, and tore the boot from its resting-place.

“I told you,” he said. “I told you.”

“I wondered where that boot had got to,” said Psmith. “I’ve been looking for it for days.”

Mr. Downing was examining his find. He looked up with an exclamation of surprise and wrath.

“This boot has no paint on it,” he said, glaring at Psmith. “This is not the boot.”

“It certainly appears, sir,” said Psmith sympathetically, “to be free from paint. There’s a sort of reddish glow just there, if you look at it sideways,” he added helpfully.

“Did you place that boot there, Smith?”

“I must have done. Then, when I lost the key——”

“Are you satisfied now, Downing?” interrupted Mr. Outwood with asperity, “or is there any more furniture you wish to break?”

The excitement of seeing his household goods smashed with a dumb-bell had made the archæological student quite a swashbuckler for the moment. A little more, and one could imagine him giving Mr. Downing a good, hard knock.

The sleuth-hound stood still for a moment, baffled. But his brain was working with the rapidity of a buzz-saw. A chance remark of Mr. Outwood’s set him fizzing off on the trail once more. Mr. Outwood had caught sight of the little pile of soot in the grate. He bent down to inspect it.

“Dear me,” he said, “I must remember to have the chimneys swept. It should have been done before.”

Mr. Downing’s eye, rolling in a fine frenzy from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven, also focussed itself on the pile of soot; and a thrill went through him. Soot in the fireplace! Smith washing his hands! (“You know my methods, my dear Watson. Apply them.”)

Mr. Downing’s mind at that moment contained one single thought; and that thought was “What ho for the chimney!”

He dived forward with a rush, nearly knocking Mr. Outwood off his feet, and thrust an arm up into the unknown. An avalanche of soot fell upon his hand and wrist, but he ignored it, for at the same instant his fingers had closed upon what he was seeking.

“Ah,” he said. “I thought as much. You were not quite clever enough, after all, Smith.”

“No, sir,” said Psmith patiently. “We all make mistakes.”

“You would have done better, Smith, not to have given me all this trouble. You have done yourself no good by it.”

“It’s been great fun, though, sir,” argued Psmith.

“Fun!” Mr. Downing laughed grimly. “You may have reason to change your opinion of what constitutes——”

His voice failed as his eye fell on the all-black toe of the boot. He looked up, and caught Psmith’s benevolent gaze. He straightened himself and brushed a bead of perspiration from his face with the back of his hand. Unfortunately, he used the sooty hand, and the result was like some gruesome burlesque of a nigger minstrel.

“Did-you-put-that-boot-there, Smith?” he asked slowly.

“Yes, sir.”

“Then what did you MEAN by putting it there?” roared Mr. Downing.

“Animal spirits, sir,” said Psmith.

“WHAT!”

“Animal spirits, sir.”

What Mr. Downing would have replied to this one cannot tell, though one can guess roughly. For, just as he was opening his mouth, Mr. Outwood, catching sight of his Chirgwin-like countenance, intervened.

“My dear Downing,” he said, “your face. It is positively covered with soot, positively. You must come and wash it. You are quite black. Really, you present a most curious appearance, most. Let me show you the way to my room.”

In all times of storm and tribulation there comes a breaking-point, a point where the spirit definitely refuses to battle any longer against the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Mr. Downing could not bear up against this crowning blow. He went down beneath it. In the language of the Ring, he took the count. It was the knock-out.

“Soot!” he murmured weakly. “Soot!”

“Your face is covered, my dear fellow, quite covered.”

“It certainly has a faintly sooty aspect, sir,” said Psmith.

His voice roused the sufferer to one last flicker of spirit.

“You will hear more of this, Smith,” he said. “I say you will hear more of it.”

Then he allowed Mr. Outwood to lead him out to a place where there were towels, soap, and sponges.

When they had gone, Psmith went to the window, and hauled in the string. He felt the calm after-glow which comes to the general after a successfully-conducted battle. It had been trying, of course, for a man of refinement, and it had cut into his afternoon, but on the whole it had been worth it.

The problem now was what to do with the painted boot. It would take a lot of cleaning, he saw, even if he could get hold of the necessary implements for cleaning it. And he rather doubted if he would be able to do so. Edmund, the boot-boy, worked in some mysterious cell, far from the madding crowd, at the back of the house. In the boot-cupboard downstairs there would probably be nothing likely to be of any use.

His fears were realised. The boot-cupboard was empty. It seemed to him that, for the time being, the best thing he could do would be to place the boot in safe hiding, until he should have thought out a scheme.

Having restored the basket to its proper place, accordingly, he went up to the study again, and placed the red-toed boot in the chimney, at about the same height where Mr. Downing had found the other. Nobody would think of looking there a second time, and it was improbable that Mr. Outwood really would have the chimneys swept, as he had said. The odds were that he had forgotten about it already.

Psmith went to the bathroom to wash his hands again, with the feeling that he had done a good day’s work.

CHAPTER XXIII.

on the trail again.

HE most massive minds are apt to

forget things at times. The most adroit plotters

make their little mistakes. Psmith was no exception

to the rule. He made the mistake of not telling

Mike of the afternoon’s happenings.

HE most massive minds are apt to

forget things at times. The most adroit plotters

make their little mistakes. Psmith was no exception

to the rule. He made the mistake of not telling

Mike of the afternoon’s happenings.

It was not altogether forgetfulness. Psmith was one of those people who like to carry through their operations entirely by themselves. Where there is only one in a secret the secret is more liable to remain unrevealed. There was nothing, he thought, to be gained from telling Mike. He forgot what the consequences might be if he did not.

So Psmith kept his own counsel, with the result that Mike went over to school on the Monday morning in pumps.

Edmund, summoned from the hinterland of the house to give his opinion why only one of Mike’s boots was to be found, had no views on the subject. He seemed to look on it as one of those things which no fellow can understand.

“ ’Ere’s one of ’em, Mr. Jackson,” he said, as if he hoped that Mike might be satisfied with a compromise.

“One? What’s the good of that, Edmund, you chump? I can’t go over to school in one boot.”

Edmund turned this over in his mind, and then said, “No, sir,” as much as to say, “I may have lost a boot, but, thank goodness, I can still understand sound reasoning.”

“Well, what am I to do? Where is the other boot?”

“Don’t know, Mr. Jackson,” replied Edmund to both questions.

“Well, I mean——Oh, dash it, there’s the bell.”

And Mike sprinted off in the pumps he stood in.

It is only a deviation from those ordinary rules of school life, which one observes naturally and without thinking, that enables one to realise how strong public school prejudices really are. At a school, for instance, where the regulations say that coats only of black or dark blue are to be worn, a boy who appears one day in even the most respectable and unostentatious brown finds himself looked on with a mixture of awe and repulsion, which would be excessive if he had sand-bagged the headmaster. So in the case of boots. School rules decree that a boy shall go to his form-room in boots. There is no real reason why, if the day is fine, he should not wear shoes, should he prefer them. But, if he does, the thing creates a perfect sensation. Boys say, “Great Scott, what have you got on?” Masters say, “Jones, what are you wearing on your feet?” In the few minutes which elapse between the assembling of the form for call-over and the arrival of the form-master, some wag is sure either to stamp on the shoes, accompanying the act with some satirical remark, or else to pull one of them off, and inaugurate an impromptu game of football with it. There was once a boy who went to school one morning in elastic-sided boots . . .

Mike had always been coldly distant in his relations to the rest of his form, looking on them, with a few exceptions, as worms; and the form, since his innings against Downing’s on the Friday, had regarded Mike with respect. So that he escaped the ragging he would have had to undergo at Wrykyn in similar circumstances. It was only Mr. Downing who gave trouble.

There is a sort of instinct which enables some masters to tell when a boy in their form is wearing shoes instead of boots, just as people who dislike cats always know when one is in a room with them. They cannot see it, but they feel it in their bones.

Mr. Downing was perhaps the most bigoted anti-shoeist in the whole list of English schoolmasters. He waged war remorselessly against shoes. Satire, abuse, lines, detention—every weapon was employed by him in dealing with their wearers. It had been the late Dunster’s practice always to go over to school in shoes when, as he usually did, he felt shaky in the morning’s lesson. Mr. Downing always detected him in the first five minutes, and that meant a lecture of anything from ten minutes to a quarter of an hour on Untidy Habits and Boys Who Looked like Loafers—which broke the back of the morning’s work nicely. On one occasion, when a particularly tricky bit of Livy was on the bill of fare, Dunster had entered the form-room in heel-less Turkish bath-slippers, of a vivid crimson; and the subsequent proceedings, including his journey over to the house to change the heel-less atrocities, had seen him through very nearly to the quarter to eleven interval.

Mike, accordingly, had not been in his place for three minutes when Mr. Downing, stiffening like a pointer, called his name.

“Yes, sir?” said Mike.

“What are you wearing on your feet, Jackson?”

“Pumps, sir.”

“You are wearing pumps? Are you not aware that pumps are not the proper things to come to school in? Why are you wearing PUMPS?”

The form, leaning back against the next row of desks, settled itself comfortably for the address from the throne.

“I have lost one of my boots, sir.”

A kind of gulp escaped from Mr. Downing’s lips. He stared at Mike for a moment in silence. Then, turning to Stone, he told him to start translating.

Stone, who had been expecting at least ten minutes’ respite, was taken unawares. When he found the place in his book and began to construe, he floundered hopelessly. But, to his growing surprise and satisfaction, the form-master appeared to notice nothing wrong. He said “Yes, yes,” mechanically, and finally “That will do,” whereupon Stone resumed his seat with the feeling that the age of miracles had returned.

Mr. Downing’s mind was in a whirl. His case was complete. Mike’s appearance in shoes, with the explanation that he had lost a boot, completed the chain. As Columbus must have felt when his ship ran into harbour, and the first American interviewer, jumping on board, said, “Wal, sir, and what are your impressions of our glorious country?” so did Mr. Downing feel at that moment.

When the bell rang at a quarter to eleven, he gathered up his gown, and sped to the headmaster.

CHAPTER XXIV.

the kettle method.

T was during the interval that day

that Stone and Robinson, discussing the subject of

cricket over a bun and gingerbeer at the school shop,

came to a momentous decision, to wit, that they were

fed up with the Adair administration and meant to strike.

The immediate cause of revolt was early-morning fielding-practice,

that searching test of cricket keenness. Mike

himself, to whom cricket was the great and serious

interest of life, had shirked early-morning fielding-practice

in his first term at Wrykyn. And Stone and Robinson

had but a lukewarm attachment to the game, compared

with Mike’s.

T was during the interval that day

that Stone and Robinson, discussing the subject of

cricket over a bun and gingerbeer at the school shop,

came to a momentous decision, to wit, that they were

fed up with the Adair administration and meant to strike.

The immediate cause of revolt was early-morning fielding-practice,

that searching test of cricket keenness. Mike

himself, to whom cricket was the great and serious

interest of life, had shirked early-morning fielding-practice

in his first term at Wrykyn. And Stone and Robinson

had but a lukewarm attachment to the game, compared

with Mike’s.

As a rule, Adair had contented himself with practice in the afternoon after school, which nobody objects to; and no strain, consequently, had been put upon Stone’s and Robinson’s allegiance. In view of the M.C.C. match on the Wednesday, however, he had now added to this an extra dose to be taken before breakfast. Stone and Robinson had left their comfortable beds that day at six o’clock, yawning and heavy-eyed, and had caught catches and fielded drives which, in the cool morning air, had stung like adders and bitten like serpents. Until the sun has really got to work, it is no joke taking a high catch. Stone’s dislike of the experiment was only equalled by Robinson’s. They were neither of them of the type which likes to undergo hardships for the common good. They played well enough when on the field, but neither cared greatly whether the school had a good season or not. They played the game entirely for their own sakes.

The result was that they went back to the house for breakfast with a never-again feeling, and at the earliest possible moment met to debate as to what was to be done about it. At all costs another experience like to-day’s must be avoided.

“It’s all rot,” said Stone. “What on earth’s the good of sweating about before breakfast? It only makes you tired.”

“I shouldn’t wonder,” said Robinson, “if it wasn’t bad for the heart. Rushing about on an empty stomach, I mean, and all that sort of thing.”

“Personally,” said Stone, gnawing his bun, “I don’t intend to stick it.”

“Nor do I.”

“I mean, it’s such absolute rot. If we aren’t good enough to play for the team without having to get up overnight to catch catches, he’d better find somebody else.”

“Yes.”

At this moment Adair came into the shop.

“Fielding-practice again to-morrow,” he said briskly, “at six.”

“Before breakfast?” said Robinson.

“Rather. You two must buck up, you know. You were rotten to-day.” And he passed on, leaving the two malcontents speechless.

Stone was the first to recover.

“I’m hanged if I turn out to-morrow,” he said, as they left the shop. “He can do what he likes about it. Besides, what can he do, after all? Only kick us out of the team. And I don’t mind that.”

“Nor do I.”

“I don’t think he will kick us out, either. He can’t play the M.C.C. with a scratch team. If he does, we’ll go and play for that village Jackson plays for. We’ll get Jackson to shove us into the team.”

“All right,” said Robinson. “Let’s.”

Their position was a strong one. A cricket captain may seem to be an autocrat of tremendous power, but in reality he has only one weapon, the keenness of those under him. With the majority, of course, the fear of being excluded or ejected from a team is a spur that drives. The majority, consequently, are easily handled. But when a cricket captain runs up against a boy who does not much care whether he plays for the team or not, then he finds himself in a difficult position, and, unless he is a man of action, practically helpless.

Stone and Robinson felt secure. Taking it all round, they felt that they would just as soon play for Lower Borlock as for the school. The bowling of the opposition would be weaker in the former case, and the chance of making runs greater. To a certain type of cricketer runs are runs, wherever and however made.

The result of all this was that Adair, turning out with the team next morning for fielding-practice, found himself two short. Barnes was among those present, but of the other two representatives of Outwood’s house there were no signs.

Barnes, questioned on the subject, had no information to give, beyond the fact that he had not seen them about anywhere. Which was not a great help. Adair proceeded with the fielding-practice without further delay.

At breakfast that morning he was silent and apparently wrapped in thought. Mr. Downing, who sat at the top of the table with Adair on his right, was accustomed at the morning meal to blend nourishment of the body with that of the mind. As a rule he had ten minutes with the daily paper before the bell rang, and it was his practice to hand on the results of his reading to Adair and the other house-prefects, who, not having seen the paper, usually formed an interested and appreciative audience. To-day, however, though the house-prefects expressed varying degrees of excitement at the news that Tyldesley had made a century against Gloucestershire, and that a butter famine was expected in the United States, these world-shaking news-items seemed to leave Adair cold. He champed his bread and marmalade with an abstracted air.

He was wondering what to do in this matter of Stone and Robinson.

Many captains might have passed the thing over. To take it for granted that the missing pair had overslept themselves would have been a safe and convenient way out of the difficulty. But Adair was not the sort of person who seeks for safe and convenient ways out of difficulties. He never shirked anything, physical or moral.

He resolved to interview the absentees.

It was not until after school that an opportunity offered itself. He went across to Outwood’s and found the two non-starters in the senior day-room, engaged in the intellectual pursuit of kicking the wall and marking the height of each kick with chalk. Adair’s entrance coincided with a record effort by Stone, which caused the kicker to overbalance and stagger backwards against the captain.

“Sorry,” said Stone. “Hullo, Adair!”

“Don’t mention it. Why weren’t you two at fielding-practice this morning?”

Robinson, who left the lead to Stone in all matters, said nothing. Stone spoke.

“We didn’t turn up,” he said.

“I know you didn’t. Why not?”

Stone had rehearsed this scene in his mind, and he spoke with the coolness which comes from rehearsal.

“We decided not to.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. We came to the conclusion that we hadn’t any use for early-morning fielding.”

Adair’s manner became ominously calm.

“You were rather fed-up, I suppose?”

“That’s just the word.”

“Sorry it bored you.”

“It didn’t. We didn’t give it the chance to.”

Robinson laughed appreciatively.

“What’s the joke, Robinson?” asked Adair.

“There’s no joke,” said Robinson, with some haste. “I was only thinking of something.”

“I’ll give you something else to think about soon.”

Stone intervened.

“It’s no good making a row about it, Adair. You must see that you can’t do anything. Of course, you can kick us out of the team, if you like, but we don’t care if you do. Jackson will get us a game any Wednesday or Saturday for the village he plays for. So we’re all right. And the school team aren’t such a lot of flyers that you can afford to go chucking people out of it whenever you want to. See what I mean?”

“You and Jackson seem to have fixed it all up between you.”

“What are you going to do? Kick us out?”

“No.”

“Good. I thought you’d see it was no good making a beastly row. We’ll play for the school all right. There’s no earthly need for us to turn out for fielding-practice before breakfast.”

“You don’t think there is? You may be right. All the same, you’re going to to-morrow morning.”

“What!”

“Six sharp. Don’t be late.”

“Don’t be an ass, Adair. We’ve told you we aren’t going to.”

“That’s only your opinion. I think you are. I’ll give you till five past six, as you seem to like lying in bed.”

“You can turn out if you feel like it. You won’t find me there.”

“That’ll be a disappointment. Nor Robinson?”

“No,” said the junior partner in the firm; but he said it without any deep conviction. The atmosphere was growing a great deal too tense for his comfort.

“You’ve quite made up your minds?”

“Yes,” said Stone.

“Right,” said Adair quietly, and knocked him down.

He was up again in a moment. Adair had pushed the table back, and was standing in the middle of the open space.

“You cad,” said Stone. “I wasn’t ready.”

“Well, you are now. Shall we go on?”

Stone dashed in without a word, and for a few moments the two might have seemed evenly matched to a not too intelligent spectator. But science tells, even in a confined space. Adair was smaller and lighter than Stone, but he was cooler and quicker, and he knew more about the game. His blow was always home a fraction of a second sooner than his opponent’s. At the end of a minute Stone was on the floor again.

He got up slowly and stood leaning with one hand on the table.

“Suppose we say ten past six?” said Adair. “I’m not particular to a minute or two.”

Stone made no reply.

“Will ten past six suit you for fielding-practice to-morrow?” said Adair.

“All right,” said Stone.

“Thanks. How about you, Robinson?”

Robinson had been a petrified spectator of the Captain-Kettle-like manœuvres of the cricket captain, and it did not take him long to make up his mind. He was not altogether a coward. In different circumstances he might have put up a respectable show. But it takes a more than ordinarily courageous person to embark on a fight which he knows must end in his destruction. Robinson knew that he was nothing like a match even for Stone, and Adair had disposed of Stone in a little over one minute. It seemed to Robinson that neither pleasure nor profit was likely to come from an encounter with Adair.

“All right,” he said hastily, “I’ll turn up.”

“Good,” said Adair. “I wonder if either of you chaps could tell me which is Jackson’s study.”

Stone was dabbing at his mouth with a handkerchief, a task which precluded anything in the shape of conversation; so Robinson replied that Mike’s study was the first you came to on the right of the corridor at the top of the stairs.

“Thanks,” said Adair. “You don’t happen to know if he’s in, I suppose?”

“He went up with Smith a quarter of an hour ago. I don’t know if he’s still there.”

“I’ll go and see,” said Adair. “I should like a word with him if he isn’t busy.”

CHAPTER XXV.

adair has a word with mike.

IKE, all unconscious of the stirring

proceedings which had been going on below stairs,

was peacefully reading a letter he had received that

morning from Strachan at Wrykyn, in which the successor

to the cricket captaincy which should have been Mike’s,

had a good deal to say in a lugubrious strain.

In Mike’s absence things had been going badly

with Wrykyn. A broken arm, contracted in the

course of some rash experiments with a day-boy’s

motor-bicycle, had deprived the team of the services

of Dunstable, the only man who had shown any signs

of being able to bowl a side out. Since this

calamity, wrote Strachan, everything had gone wrong.

The M.C.C., led by Mike’s brother Reggie, the

least of the three first-class-cricketing Jacksons,

had smashed them by a hundred and fifty runs.

Geddington had wiped them off the face of the earth.

The Incogs, with a team recruited exclusively from

the rabbit-hutch—not a well-known man on

the side except Stacey, a veteran who had been playing

for the club since Fuller Pilch’s time—had

got home by two wickets. In fact, it was Strachan’s

opinion that the Wrykyn team that summer was about

the most hopeless gang of dead-beats that had ever

made an exhibition of itself on the school grounds.

The Ripton match, fortunately, was off, owing to an

outbreak of mumps at that shrine of learning and athletics—the

second outbreak of the malady in two terms. Which,

said Strachan, was hard lines on Ripton, but a bit

of jolly good luck for Wrykyn, as it had saved them

from what would probably have been a record hammering,

Ripton having eight of their last year’s team

left, including Dixon, the fast bowler, against whom

Mike alone of the Wrykyn team had been able to make

runs in the previous season. Altogether, Wrykyn

had struck a bad patch.

IKE, all unconscious of the stirring

proceedings which had been going on below stairs,

was peacefully reading a letter he had received that

morning from Strachan at Wrykyn, in which the successor

to the cricket captaincy which should have been Mike’s,

had a good deal to say in a lugubrious strain.

In Mike’s absence things had been going badly

with Wrykyn. A broken arm, contracted in the

course of some rash experiments with a day-boy’s

motor-bicycle, had deprived the team of the services

of Dunstable, the only man who had shown any signs

of being able to bowl a side out. Since this

calamity, wrote Strachan, everything had gone wrong.

The M.C.C., led by Mike’s brother Reggie, the

least of the three first-class-cricketing Jacksons,

had smashed them by a hundred and fifty runs.

Geddington had wiped them off the face of the earth.

The Incogs, with a team recruited exclusively from

the rabbit-hutch—not a well-known man on

the side except Stacey, a veteran who had been playing

for the club since Fuller Pilch’s time—had

got home by two wickets. In fact, it was Strachan’s

opinion that the Wrykyn team that summer was about

the most hopeless gang of dead-beats that had ever

made an exhibition of itself on the school grounds.

The Ripton match, fortunately, was off, owing to an

outbreak of mumps at that shrine of learning and athletics—the

second outbreak of the malady in two terms. Which,

said Strachan, was hard lines on Ripton, but a bit

of jolly good luck for Wrykyn, as it had saved them

from what would probably have been a record hammering,

Ripton having eight of their last year’s team

left, including Dixon, the fast bowler, against whom

Mike alone of the Wrykyn team had been able to make

runs in the previous season. Altogether, Wrykyn

had struck a bad patch.

Mike mourned over his suffering school. If only he could have been there to help. It might have made all the difference. In school cricket one good batsman, to go in first and knock the bowlers off their length, may take a weak team triumphantly through a season. In school cricket the importance of a good start for the first wicket is incalculable.

As he put Strachan’s letter away in his pocket, all his old bitterness against Sedleigh, which had been ebbing during the past few days, returned with a rush. He was conscious once more of that feeling of personal injury which had made him hate his new school on the first day of term.

And it was at this point, when his resentment was at its height, that Adair, the concrete representative of everything Sedleighan, entered the room.

There are moments in life’s placid course when there has got to be the biggest kind of row. This was one of them.

Psmith, who was leaning against the mantelpiece, reading the serial story in a daily paper which he had abstracted from the senior day-room, made the intruder free of the study with a dignified wave of the hand, and went on reading. Mike remained in the deck-chair in which he was sitting, and contented himself with glaring at the newcomer.

Psmith was the first to speak.

“If you ask my candid opinion,” he said, looking up from his paper, “I should say that young Lord Antony Trefusis was in the soup already. I seem to see the consommé splashing about his ankles. He’s had a note telling him to be under the oak-tree in the Park at midnight. He’s just off there at the end of this instalment. I bet Long Jack, the poacher, is waiting there with a sandbag. Care to see the paper, Comrade Adair? Or don’t you take any interest in contemporary literature?”

“Thanks,” said Adair. “I just wanted to speak to Jackson for a minute.”

“Fate,” said Psmith, “has led your footsteps to the right place. That is Comrade Jackson, the Pride of the School, sitting before you.”

“What do you want?” said Mike.

He suspected that Adair had come to ask him once again to play for the school. The fact that the M.C.C. match was on the following day made this a probable solution of the reason for his visit. He could think of no other errand that was likely to have set the head of Downing’s paying afternoon calls.

“I’ll tell you in a minute. It won’t take long.”

“That,” said Psmith approvingly, “is right. Speed is the key-note of the present age. Promptitude. Despatch. This is no time for loitering. We must be strenuous. We must hustle. We must Do It Now. We——”

“Buck up,” said Mike.

“Certainly,” said Adair. “I’ve just been talking to Stone and Robinson.”

“An excellent way of passing an idle half-hour,” said Psmith.

“We weren’t exactly idle,” said Adair grimly. “It didn’t last long, but it was pretty lively while it did. Stone chucked it after the first round.”

Mike got up out of his chair. He could not quite follow what all this was about, but there was no mistaking the truculence of Adair’s manner. For some reason, which might possibly be made clear later, Adair was looking for trouble, and Mike in his present mood felt that it would be a privilege to see that he got it.

Psmith was regarding Adair through his eyeglass with pain and surprise.

“Surely,” he said, “you do not mean us to understand that you have been brawling with Comrade Stone! This is bad hearing. I thought that you and he were like brothers. Such a bad example for Comrade Robinson, too. Leave us, Adair. We would brood. Oh, go thee, knave, I’ll none of thee. Shakespeare.”

Psmith turned away, and resting his elbows on the mantelpiece, gazed at himself mournfully in the looking-glass.

“I’m not the man I was,” he sighed, after a prolonged inspection. “There are lines on my face, dark circles beneath my eyes. The fierce rush of life at Sedleigh is wasting me away.”

“Stone and I had a discussion about early-morning fielding-practice,” said Adair, turning to Mike.

Mike said nothing.

“I thought his fielding wanted working up a bit, so I told him to turn out at six to-morrow morning. He said he wouldn’t, so we argued it out. He’s going to all right. So is Robinson.”

Mike remained silent.

“So are you,” added Adair.

“I get thinner and thinner,” said Psmith from the mantelpiece.

Mike looked at Adair, and Adair looked at Mike, after the manner of two dogs before they fly at one another. There was an electric silence in the study. Psmith peered with increased earnestness into the glass.

“Oh?” said Mike at last. “What makes you think that?”

“I don’t think. I know.”

“Any special reason for my turning out?”

“Yes.”

“What’s that?”

“You’re going to play for the school against the M.C.C. to-morrow, and I want you to get some practice.”

“I wonder how you got that idea!”

“Curious I should have done, isn’t it?”

“Very. You aren’t building on it much, are you?” said Mike politely.

“I am, rather,” replied Adair with equal courtesy.

“I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed.”

“I don’t think so.”

“My eyes,” said Psmith regretfully, “are a bit close together. However,” he added philosophically, “it’s too late to alter that now.”

Mike drew a step closer to Adair.

“What makes you think I shall play against the M.C.C.?” he asked curiously.

“I’m going to make you.”

Mike took another step forward. Adair moved to meet him.

“Would you care to try now?” said Mike.

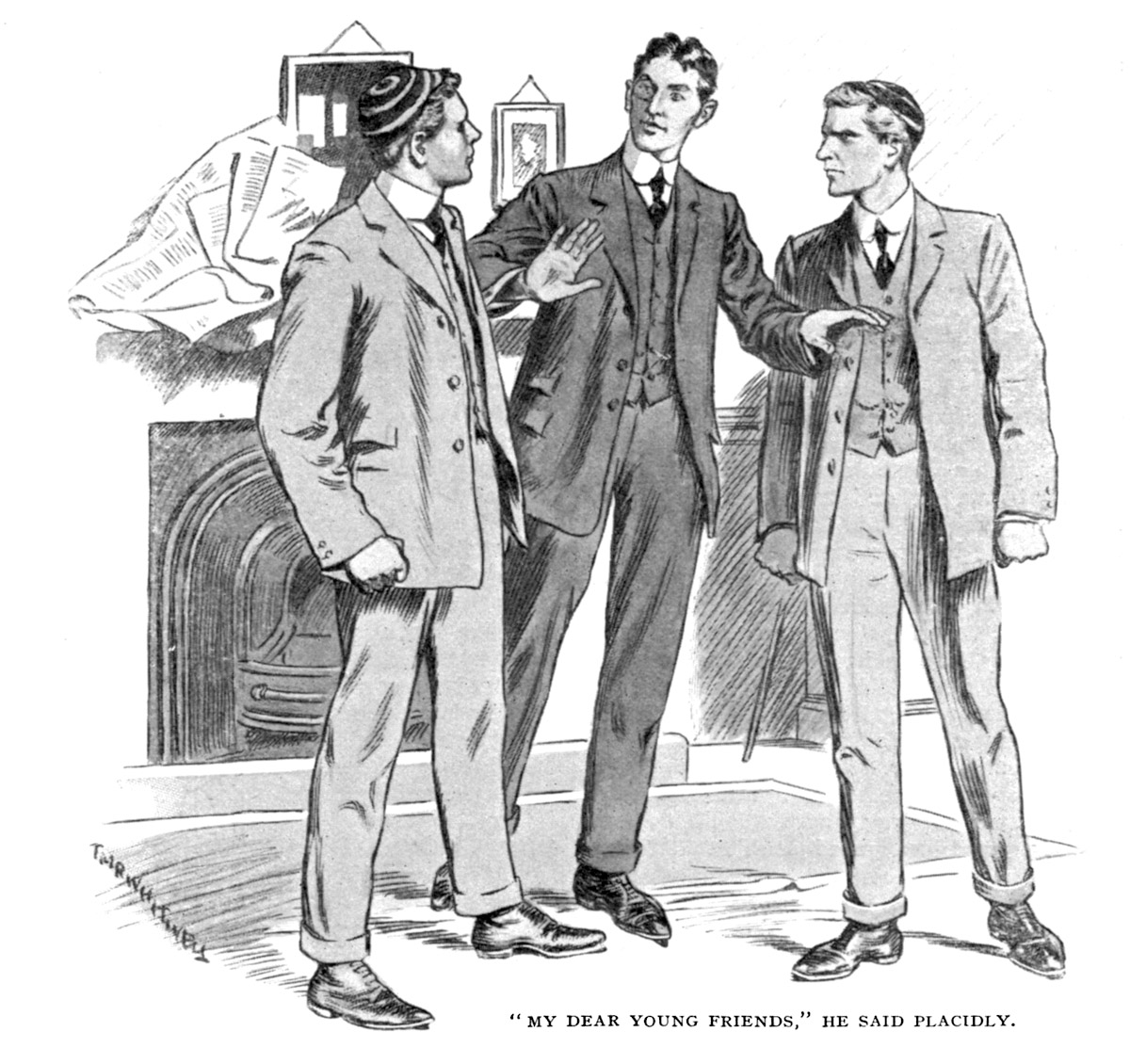

For just one second the two drew themselves together preparatory to beginning the serious business of the interview, and in that second Psmith, turning from the glass, stepped between them.

“Get out of the light, Smith,” said Mike.

Psmith waved him back with a deprecating gesture.

“My dear young friends,” he said placidly, “if you will let your angry passions rise, against the direct advice of Doctor Watts, I suppose you must. But when you propose to claw each other in my study, in the midst of a hundred fragile and priceless ornaments, I lodge a protest. If you really feel that you want to scrap, for goodness sake do it where there’s some room. I don’t want all the study furniture smashed. I know a bank whereon the wild thyme grows, only a few yards down the road, where you can scrap all night if you want to. How would it be to move on there? Any objections? None? Then shift ho, and let’s get it over.”

(To be concluded.)

Printer’s error corrected above:

In Ch. 22, magazine had “Good-Gracoius-”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums