The Captain, February 1910

* Former tales about “Psmith” are “The Lost Lambs” and “The New Fold,” in Vols. XIX and XX of The Captain.

CHAPTER XXI.

the battle of pleasant street.

HE new arrival was a young man with a shock of red hair, an

ingrowing Roman nose, and a mouth from which force or the passage of time had

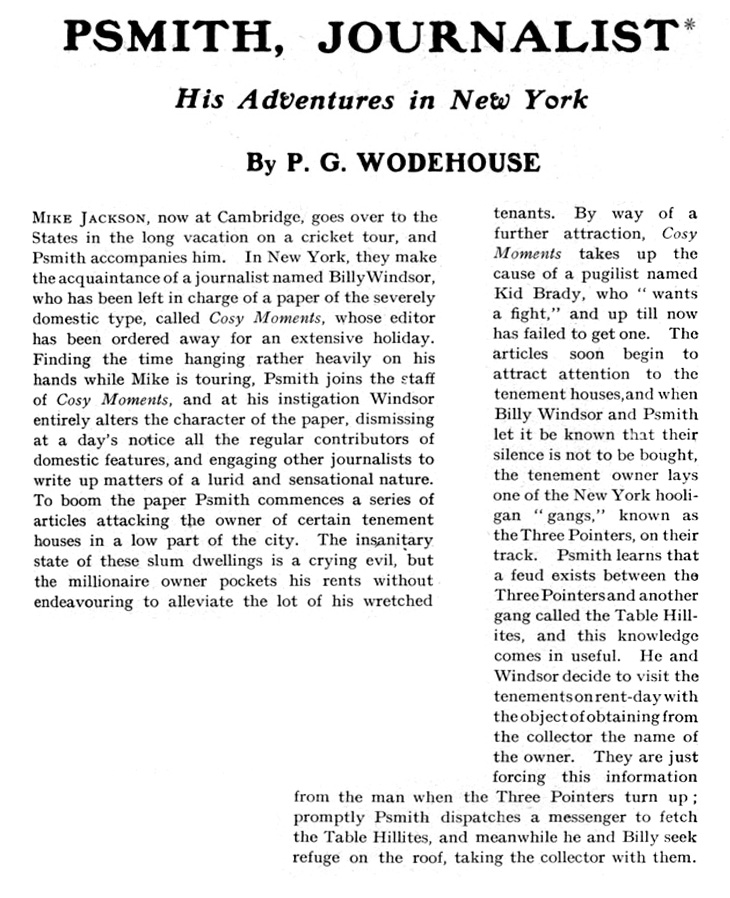

removed three front teeth. He held on to the edges of the trap with his hands,

and stared in a glassy manner into Psmith’s face, which was within a foot of his

own.

HE new arrival was a young man with a shock of red hair, an

ingrowing Roman nose, and a mouth from which force or the passage of time had

removed three front teeth. He held on to the edges of the trap with his hands,

and stared in a glassy manner into Psmith’s face, which was within a foot of his

own.

There was a momentary pause, broken by an oath from Mr. Gooch, who was still undergoing treatment in the background.

“Aha!” said Psmith genially. “Historic picture. ‘Doctor Cook discovers the North Pole.’ ”

The red-headed young man blinked. The strong light of the open air was trying to his eyes.

“Youse had better come down,” he observed coldly. “We’ve got youse.”

“And,” continued Psmith, unmoved, “is instantly handed a gum-drop by his faithful Esquimaux.”

As he spoke, he brought the stick down on the knuckles which disfigured the edges of the trap. The intruder uttered a howl and dropped out of sight. In the room below there were whisperings and mutterings, growing gradually louder till something resembling coherent conversation came to Psmith’s ears, as he knelt by the trap making meditative billiard-shots with the stick at a small pebble.

“Aw g’wan! Don’t be a quitter!”

“Who’s a quitter?”

“Youse is a quitter. Get on top de roof. He can’t hoit youse.”

“De guy’s gotten a big stick.”

Psmith nodded appreciatively.

“I and Roosevelt,” he murmured.

A somewhat baffled silence on the part of the attacking force was followed by further conversation.

“Gum! some guy’s got to go up.”

Murmur of assent from the audience.

A voice, in inspired tones: “Let Sam do it!”

This suggestion made a hit. There was no doubt about that. It was a success from the start. Quite a little chorus of voices expressed sincere approval of the very happy solution to what had seemed an insoluble problem. Psmith, listening from above, failed to detect in the choir of glad voices one that might belong to Sam himself. Probably gratification had rendered the chosen one dumb.

“Yes, let Sam do it!” cried the unseen chorus. The first speaker, unnecessarily, perhaps—for the motion had been carried almost unanimously—but possibly with the idea of convincing the one member of the party in whose bosom doubts might conceivably be harboured, went on to adduce reasons.

“Sam bein’ a coon,” he argued, “ain’t goin’ to git hoit by no stick. Youse can’t hoit a coon by soakin’ him on de coco, can you, Sam?”

Psmith waited with some interest for the reply, but it did not come. Possibly Sam did not wish to generalise on insufficient experience.

“Solvitur ambulando,” said Psmith softly, turning the stick round in his fingers. “Comrade Windsor!”

“Hullo!”

“Is it possible to hurt a coloured gentleman by hitting him on the head with a stick?”

“If you hit him hard enough.”

“I knew there was some way out of the difficulty,” said Psmith with satisfaction. “How are you getting on up at your end of the table, Comrade Windsor?”

“Fine.”

“Any result yet?”

“Not at present.”

“Don’t give up.”

“Not me.”

“The right spirit, Comrade Win——”

A report like a cannon in the room below interrupted him. It was merely a revolver shot, but in the confined space it was deafening. The bullet sang up into the sky.

“Never hit me!” said Psmith with dignified triumph.

The noise was succeeded by a shuffling of feet. Psmith grasped his stick more firmly. This was evidently the real attack. The revolver shot had been a mere demonstration of artillery to cover the infantry’s advance.

Sure enough, the next moment a woolly head popped through the opening, and a pair of rolling eyes gleamed up at the old Etonian.

“Why, Sam!” said Psmith cordially, “this is well met! I remember you. Yes, indeed, I do. Wasn’t you the feller with the open umbereller that I met one rainy morning on the Av-en-ue? What, are you coming up? Sam, I hate to do it, but—”

A yell rang out.

“What was that?” asked Billy Windsor over his shoulder.

“Your statement, Comrade Windsor, has been tested and proved correct.”

By this time the affair had begun to draw a “gate.” The noise of the revolver had proved a fine advertisement. The roof of the house next door began to fill up. Only a few of the occupants could get a clear view of the proceedings, for a large chimney-stack intervened. There was considerable speculation as to what was passing between Billy Windsor and Mr. Gooch. Psmith’s share in the entertainment was more obvious. The early comers had seen his interview with Sam, and were relating it with gusto to their friends. Their attitude towards Psmith was that of a group of men watching a terrier at a rat-hole. They looked to him to provide entertainment for them, but they realised that the first move must be with the attackers. They were fair-minded men, and they did not expect Psmith to make any aggressive move.

Their indignation, when the proceedings began to grow slow, was directed entirely at the dilatory Three Pointers. With an aggrieved air, akin to that of a crowd at a cricket match when batsmen are playing for a draw, they began to “barrack.” They hooted the Three Pointers. They begged them to go home and tuck themselves up in bed. The men on the roof were mostly Irishmen, and it offended them to see what should have been a spirited fight so grossly bungled.

“G’wan away home, ye quitters!” roared one.

“Call yersilves the Three Points, do ye? An’ would ye know what I call ye? The Young Ladies’ Seminary!” bellowed another with withering scorn.

A third member of the audience alluded to them as “stiffs.”

“I fear, Comrade Windsor,” said Psmith, “that our blithe friends below are beginning to grow a little unpopular with the many-headed. They must be up and doing if they wish to retain the esteem of Pleasant Street. Aha!”

Another and a longer explosion from below, and more bullets wasted themselves on air. Psmith sighed.

“They make me tired,” he said. “This is no time for a feu-de-joie. Action! That is the cry. Action! Get busy, you blighters!”

The Irish neighbours expressed the same sentiment in different and more forcible words. There was no doubt about it—as warriors, the Three Pointers had failed to give satisfaction.

A voice from the room called up to Psmith.

“Say!”

“You have our ear,” said Psmith.

“What’s that?”

“I said you had our ear.”

“Are youse stiffs comin’ down off out of dat roof?”

“Would you mind repeating that remark?”

“Are youse guys goin’ to quit off out of dat roof?”

“Your grammar is perfectly beastly,” said Psmith severely.

“Hey!”

“Well?”

“Are youse guys——?”

“No, my lad,” said Psmith, “since you ask, we are not. And why? Because the air up here is refreshing, the view pleasant, and we are expecting at any moment an important communication from Comrade Gooch.”

“We’re goin’ to wait here till youse come down.”

“If you wish it,” said Psmith courteously, “by all means do. Who am I that I should dictate your movements? The most I aspire to is to check them when they take an upward direction.”

There was silence below. The time began to pass slowly. The Irishmen on the other roof, now definitely abandoning hope of further entertainment, proceeded with hoots of scorn to climb down one by one into the recesses of their own house.

Suddenly from the street far below there came a fusillade of shots and a babel of shouts and counter-shouts. The roof of the house next door, which had been emptying itself slowly and reluctantly, filled again with a magical swiftness, and the low wall facing into the street became black with the backs of those craning over.

“What’s that?” inquired Billy.

“I rather fancy,” said Psmith, “that our allies of the Table Hill contingent must have arrived. I sent Comrade Maloney to explain matters to Dude Dawson, and it seems as if that golden-hearted sportsman had responded. There appear to be great doings in the street.”

In the room below confusion had arisen. A scout, clattering upstairs, had brought the news of the Table Hillites’ advent, and there was doubt as to the proper course to pursue. Certain voices urged going down to help the main body. Others pointed out that that would mean abandoning the siege of the roof. The scout who had brought the news was eloquent in favour of the first course.

“Gum!” he cried, “don’t I keep tellin’ youse dat de Table Hills is here? Sure, dere’s a whole bunch of dem, and unless youse come on down dey’ll bite de hull head off of us lot. Leave those stiffs on de roof. Let Sam wait here with his canister, and den dey can’t get down, ’cos Sam’ll pump dem full of lead while dey’re beatin’ it t’roo de trap-door. Sure.”

Psmith nodded reflectively.

“There is certainly something in what the bright boy says,” he murmured. “It seems to me the grand rescue scene in the third act has sprung a leak. This will want thinking over.”

In the street the disturbance had now become terrific. Both sides were hard at it, and the Irishmen on the roof, rewarded at last for their long vigil, were yelling encouragement promiscuously and whooping with the unfettered ecstasy of men who are getting the treat of their lives without having paid a penny for it.

The behaviour of the New York policeman in affairs of this kind is based on principles of the soundest practical wisdom. The unthinking man would rush in and attempt to crush the combat in its earliest and fiercest stages. The New York policeman, knowing the importance of his own safety, and the insignificance of the gangsman’s, permits the opposing forces to hammer each other into a certain distaste for battle, and then, when both sides have begun to have enough of it, rushes in himself and clubs everything in sight. It is an admirable process in its results, but it is sure rather than swift.

Proceedings in the affair below had not yet reached the police interference stage. The noise, what with the shots and yells from the street and the ear-piercing approval of the roof-audience, was just working up to a climax.

Psmith rose. He was tired of kneeling by the trap, and there was no likelihood of Sam making another attempt to climb through. He walked towards Billy.

As he did so, Billy got up and turned to him. His eyes were gleaming with excitement. His whole attitude was triumphant. In his hand he waved a strip of paper.

“I’ve got it,” he cried.

“Excellent, Comrade Windsor,” said Psmith. “Surely we must win through now. All we have to do is to get off this roof, and fate cannot touch us. Are two mammoth minds such as ours unequal to such a feat? It can hardly be. Let us ponder.”

“Why not go down through the trap? They’ve all gone to the street.”

Psmith shook his head.

“All,” he replied, “save Sam. Sam was the subject of my late successful experiment, when I proved that coloured gentlemen’s heads could be hurt with a stick. He is now waiting below, armed with a pistol, ready—even anxious—to pick us off as we climb through the trap. How would it be to drop Comrade Gooch through first, and so draw his fire? Comrade Gooch, I am sure, would be delighted to do a little thing like that for old friends of our standing or—but what’s that!”

“What’s the matter?”

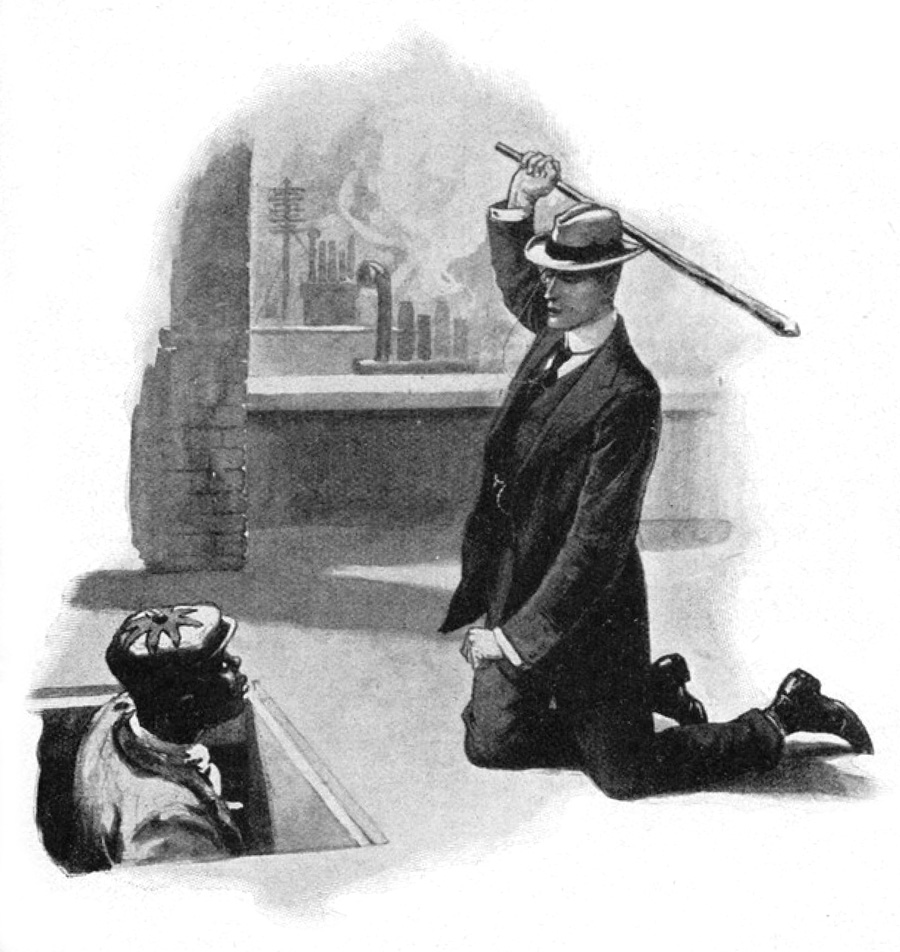

“Is that a ladder that I see before me, its handle to my hand? It is! Comrade Windsor, we win through. Cosy Moments’ editorial staff may be tree’d, but it cannot be put out of business. Comrade Windsor, take the other end of that ladder and follow me.”

The ladder was lying against the farther wall. It was long, more than long enough for the purpose for which it was needed. Psmith and Billy rested it on the coping, and pushed it till the other end reached across the gulf to the roof of the house next door, Mr. Gooch eyeing them in silence the while.

Psmith turned to him.

“Comrade Gooch,” he said, “do nothing to apprise our friend Sam of these proceedings. I speak in your best interests. Sam is in no mood to make nice distinctions between friend and foe. If you bring him up here, he will probably mistake you for a member of the staff of Cosy Moments, and loose off in your direction without waiting for explanations. I think you had better come with us. I will go first, Comrade Windsor, so that if the ladder breaks, the paper will lose merely a sub-editor, not an editor.”

He went down on all-fours, and in this attitude wormed his way across to the opposite roof, whose occupants, engrossed in the fight in the street, in which the police had now joined, had their backs turned and did not observe him. Mr. Gooch, pallid and obviously ill-attuned to such feats, followed him; and finally Billy Windsor reached the other side.

“Neat,” said Psmith complacently. “Uncommonly neat. Comrade Gooch reminded me of the untamed chamois of the Alps, leaping from crag to crag.”

In the street there was now comparative silence. The police, with their clubs, had knocked the last remnant of fight out of the combatants. Shooting had definitely ceased.

“I think,” said Psmith, “that we might now descend. If you have no other engagements, Comrade Windsor, I will take you to the Knickerbocker, and buy you a square meal. I would ask for the pleasure of your company also, Comrade Gooch, were it not that matters of private moment, relating to the policy of the paper, must be discussed at the table. Some other day, perhaps. We are infinitely obliged to you for your sympathetic co-operation in this little matter. And now good-bye. Comrade Windsor, let us debouch.”

CHAPTER XXII.

concerning mr. waring.

SMITH pushed back his chair slightly, stretched out his legs,

and lit a cigarette. The resources of the Knickerbocker Hotel had proved equal

to supplying the fatigued staff of Cosy Moments with an excellent dinner,

and Psmith had stoutly declined to talk business until the coffee arrived. This

had been hard on Billy, who was bursting with his news. Beyond a hint that it

was sensational he had not been permitted to go.

SMITH pushed back his chair slightly, stretched out his legs,

and lit a cigarette. The resources of the Knickerbocker Hotel had proved equal

to supplying the fatigued staff of Cosy Moments with an excellent dinner,

and Psmith had stoutly declined to talk business until the coffee arrived. This

had been hard on Billy, who was bursting with his news. Beyond a hint that it

was sensational he had not been permitted to go.

“More bright young careers than I care to think of,” said Psmith, “have been ruined by the fatal practice of talking shop at dinner. But now that we are through, Comrade Windsor, by all means let us have it. What’s the name which Comrade Gooch so eagerly divulged?”

Billy leaned forward excitedly.

“Stewart Waring,” he whispered.

“Stewart who?” asked Psmith.

Billy stared.

“Great Scott, man!” he said, “haven’t you heard of Stewart Waring?”

“The name seems vaguely familiar, like isinglass or Post-toasties. I seem to know it, but it conveys nothing to me.”

“Don’t you ever read the papers?”

“I toy with my American of a morning, but my interest is confined mainly to the sporting page, which reminds me that Comrade Brady has been matched against one Eddie Wood a month from to-day. Gratifying as it is to find one of the staff getting on in life, I fear this will cause us a certain amount of inconvenience. Comrade Brady will have to leave the office temporarily in order to go into training, and what shall we do then for a fighting editor? However, possibly we may not need one now. Cosy Moments should be able shortly to give its message to the world and ease up for a while. Which brings us back to the point. Who is Stewart Waring?”

“Stewart Waring is running for City Alderman. He’s one of the biggest men in New York!”

“Do you mean in girth? If so, he seems to have selected the right career for himself.”

“He’s one of the bosses. He used to be Commissioner of Buildings for the city.”

“Commissioner of Buildings? What exactly did that let him in for?”

“It let him in for a lot of graft.”

“How was that?”

“Oh, he took it off the contractors. Shut his eyes and held out his hands when they ran up rotten buildings that a strong breeze would have knocked down, and places like that Pleasant Street hole without any ventilation.”

“Why did he throw up the job?” inquired Psmith. “It seems to me that it was among the World’s Softest. Certain drawbacks to it, perhaps, to the man with the Hair-Trigger Conscience; but I gather that Comrade Waring did not line up in that class. What was his trouble?”

“His trouble,” said Billy, “was that he stood in with a contractor who was putting up a music-hall, and the contractor put it up with material about as strong as a heap of meringues, and it collapsed on the third night and killed half the audience.”

“And then?”

“The papers raised a howl, and they got after the contractor, and the contractor gave Waring away. It killed him for the time being.”

“I should have thought it would have had that excellent result permanently,” said Psmith thoughtfully. “Do you mean to say he got back again after that?”

“He had to quit being Commissioner, of course, and leave the town for a time; but affairs move so fast here that a thing like that blows over. He made a bit of a pile out of the job, and could afford to lie low for a year or two.”

“How long ago was that?”

“Five years. People don’t remember a thing here that happened five years back unless they’re reminded of it.”

Psmith lit another cigarette.

“We will remind them,” he said.

Billy nodded.

“Of course,” he said, “one or two of the papers against him in this Aldermanic Election business tried to bring the thing up, but they didn’t cut any ice. The other papers said it was a shame, hounding a man who was sorry for the past and who was trying to make good now; so they dropped it. Everybody thought that Waring was on the level now. He’s been shooting off a lot of hot air lately about philanthropy and so on. Not that he has actually done a thing—not so much as given a supper to a dozen news-boys; but he’s talked, and talk gets over if you keep it up long enough.”

Psmith nodded adhesion to this dictum.

“So that naturally he wants to keep it dark about these tenements. It’ll smash him at the election when it gets known.”

“Why is he so set on becoming an Alderman?” inquired Psmith.

“There’s a lot of graft to being an Alderman,” explained Billy.

“I see. No wonder the poor gentleman was so energetic in his methods. What is our move now, Comrade Windsor?”

Billy stared.

“Why, publish the name, of course.”

“But before then? How are we going to ensure the safety of our evidence? We stand or fall entirely by that slip of paper, because we’ve got the beggar’s name in the writing of his own collector, and that’s proof positive.”

“That’s all right,” said Billy, patting his breast-pocket. “Nobody’s going to get it from me.”

Psmith dipped his hand into his trouser-pocket.

“Comrade Windsor,” he said, producing a piece of paper, “how do we go?”

He leaned back in his chair, surveying Billy blandly through his eye-glass. Billy’s eyes were goggling. He looked from Psmith to the paper and from the paper to Psmith.

“What—what the——?” he stammered. “Why, it’s it!”

Psmith nodded.

“How on earth did you get it?”

Psmith knocked the ash off his cigarette.

“Comrade Windsor,” he said, “I do not wish to cavil or carp or rub it in in any way. I will merely remark that you pretty nearly landed us in the soup, and pass on to more congenial topics. Didn’t you know we were followed to this place?”

“Followed!”

“By a merchant in what Comrade Maloney would call a tall-shaped hat. I spotted him at an early date, somewhere down by Twenty-ninth Street. When we dived into Sixth Avenue for a space at Thirty-third Street, did he dive, too? He did. And when we turned into Forty-second Street, there he was. I tell you, Comrade Windsor, leeches were aloof, and burrs non-adhesive compared with that tall-shaped-hatted blighter.”

“Yes?”

“Do you remember, as you came to the entrance of this place, somebody knocking against you?”

“Yes, there was a pretty big crush in the entrance.”

“There was; but not so big as all that. There was plenty of room for this merchant to pass if he had wished. Instead of which he butted into you. I happened to be waiting for just that, so I managed to attach myself to his wrist with some vim and give it a fairly hefty wrench. The paper was inside his hand.”

Billy was leaning forward with a pale face.

“Jove!” he muttered.

“That about sums it up,” said Psmith.

Billy snatched the paper from the table and extended it towards him.

“Here,” he said feverishly, “You take it. Gum, I never thought I was such a mutt! I’m not fit to take charge of a toothpick. Fancy me not being on the watch for something of that sort. I guess I was so tickled with myself at the thought of having got the thing, that it never struck me they might try for it. But I’m through. No more for me. You’re the man in charge now.”

Psmith shook his head.

“These stately compliments,” he said, “do my old heart good, but I fancy I know a better plan. It happened that I chanced to have my eye on the blighter in the tall-shaped hat, and so was enabled to land him among the ribstones; but who knows but that in the crowd on Broadway there may not lurk other, unidentified blighters in equally tall-shaped hats, one of whom may work the same sleight-of-hand speciality on me? It was not that you were not capable of taking care of that paper: it was simply that you didn’t happen to spot the man. Now observe me closely, for what follows is an exhibition of Brain.”

He paid the bill, and they went out into the entrance-hall of the hotel. Psmith, sitting down at a table, placed the paper in an envelope and addressed it to himself at the address of Cosy Moments. After which, he stamped the envelope and dropped it into the letter-box at the back of the hall.

“And now, Comrade Windsor,” he said, “let us stroll gently homewards down the Great White Way. What matter though it be fairly stiff with low-browed bravoes in tall-shaped hats? They cannot harm us. From me, if they search me thoroughly, they may scoop a matter of eleven dollars, a watch, two stamps, and a packet of chewing-gum. Whether they would do any better with you I do not know. At any rate, they wouldn’t get that paper; and that’s the main thing.”

“You’re a genius,” said Billy Windsor.

“You think so?” said Psmith diffidently. “Well, well, perhaps you are right, perhaps you are right. Did you notice the hired ruffian in the flannel suit who just passed? He wore a baffled look, I fancy. And hark! Wasn’t that a muttered ‘Failed!’ I heard? Or was it the breeze moaning in the tree-tops? To-night is a cold, disappointing night for Hired Ruffians, Comrade Windsor.”

CHAPTER XXIII.

reductions in the staff.

HE first member of the staff of Cosy Moments to arrive

at the office on the following morning was Master Maloney. This sounds like the

beginning of a “Plod and Punctuality,” or “How Great Fortunes have been Made”

story; but, as a matter of fact, Master Maloney was no early bird. Larks who

rose in his neighbourhood, rose alone. He did not get up with them. He was

supposed to be at the office at nine o’clock. It was a point of honour with him,

a sort of daily declaration of independence, never to put in an appearance

before nine-thirty. On this particular morning he was punctual to the minute, or

half an hour late, whichever way you choose to look at it.

HE first member of the staff of Cosy Moments to arrive

at the office on the following morning was Master Maloney. This sounds like the

beginning of a “Plod and Punctuality,” or “How Great Fortunes have been Made”

story; but, as a matter of fact, Master Maloney was no early bird. Larks who

rose in his neighbourhood, rose alone. He did not get up with them. He was

supposed to be at the office at nine o’clock. It was a point of honour with him,

a sort of daily declaration of independence, never to put in an appearance

before nine-thirty. On this particular morning he was punctual to the minute, or

half an hour late, whichever way you choose to look at it.

He had only whistled a few bars of “My Little Irish Rose,” and had barely got into the first page of his story of life on the prairie when Kid Brady appeared. The Kid, as was his habit when not in training, was smoking a big black cigar. Master Maloney eyed him admiringly. The Kid, unknown to that gentleman himself, was Pugsy’s ideal. He came from the Plains; and had, indeed, once actually been a cowboy; he was a coming champion; and he could smoke black cigars. It was, therefore, without his usual well-what-is-it-now? air that Pugsy laid down his book, and prepared to converse.

“Say, Mr. Smith or Mr. Windsor about, Pugsy?” asked the Kid.

“Naw, Mr. Brady, they ain’t came yet,” replied Master Maloney respectfully.

“Late, ain’t they?”

“Sure. Mr. Windsor generally blows in before I do.”

“Wonder what’s keepin’ them.”

“P’raps dey’ve bin put out of business,” suggested Pugsy nonchalantly.

“How’s that?”

Pugsy related the events of the previous day, relaxing something of his austere calm as he did so. When he came to the part where the Table Hill allies swooped down on the unsuspecting Three Pointers, he was almost animated.

“Say,” said the Kid approvingly, “that Smith guy’s got more grey matter under his thatch than you’d think to look at him. I——”

“Comrade Brady,” said a voice in the doorway, “You do me proud.”

“Why, say,” said the Kid, turning, “I guess the laugh’s on me. I didn’t see you, Mr. Smith. Pugsy’s been tellin’ me how you sent him for the Table Hills yesterday. That was cute. It was mighty smart. But say, those guys are goin’ some, ain’t they now! Seems as if they was dead set on puttin’ you out of business.”

“Their manner yesterday, Comrade Brady, certainly suggested the presence of some sketchy outline of such an ideal in their minds. One Sam, in particular, an ebony-hued sportsman, threw himself into the task with great vim. I rather fancy he is waiting for us with his revolver to this moment. But why worry? Here we are, safe and sound, and Comrade Windsor may be expected to arrive at any moment. I see, Comrade Brady, that you have been matched against one Eddie Wood.”

“It’s about that I wanted to see you, Mr. Smith. Say, now that things have been and brushed up so, what with these gang guys layin’ for you the way they’re doin’, I guess you’ll be needin’ me around here. Isn’t that right? Say the word and I’ll call off this Eddie Wood fight.”

“Comrade Brady,” said Psmith with some enthusiasm, “I call that a sporting offer. I’m very much obliged. But we mustn’t stand in your way. If you eliminate this Comrade Wood, they will have to give you a chance against Jimmy Garvin, won’t they?”

“I guess that’s right, sir,” said the Kid. “Eddie stayed nineteen rounds against Jimmy, and if I can put him away, it gets me into line with Jimmy, and he can’t side-step me.”

“Then go in and win, Comrade Brady. We shall miss you. It will be as if a ray of sunshine had been removed from the office. But you mustn’t throw a chance away. We shall be all right, I think.”

“I’ll train at White Plains,” said the Kid. “That ain’t far from here, so I’ll be pretty near in case I’m wanted. Hullo, who’s here?”

He pointed to the door. A small boy was standing there, holding a note.

“Mr. Smith?”

“Sir to you,” said Psmith courteously.

“P. Smith?”

“The same. This is your lucky day.”

“Cop at Jefferson Market give me dis to take to youse.”

“A cop in Jefferson Market?” repeated Psmith. “I did not know I had friends among the constabulary there. Why, it’s from Comrade Windsor.” He opened the envelope and read the letter. “Thanks,” he said, giving the boy a quarter-dollar.

It was apparent the Kid was politely endeavouring to veil his curiosity. Master Maloney had no such scruples.

“What’s in de letter, boss?” he inquired.

“The letter, Comrade Maloney, is from our Mr. Windsor, and relates in terse language the following facts, that our editor last night hit a policeman in the eye, and that he was sentenced this morning to thirty days on Blackwell’s Island.”

“He’s de guy!” admitted Master Maloney approvingly.

“What’s that?” said the Kid. “Mr. Windsor bin punchin’ cops! What’s he bin doin’ that for?”

“He gives no clue. I must go and find out. Could you help Comrade Maloney mind the shop for a few moments while I push round to Jefferson Market and make inquiries?”

“Sure. But say, fancy Mr. Windsor cuttin’ loose that way!” said the Kid admiringly.

The Jefferson Market Police Court is a little way down town, near Washington Square. It did not take Psmith long to reach it, and by the judicious expenditure of a few dollars he was enabled to obtain an interview with Billy in a back room.

The chief editor of Cosy Moments was seated on a bench, looking upon the world through a pair of much blackened eyes. His general appearance was dishevelled. He had the air of a man who has been caught in the machinery.

“Hullo, Smith,” he said. “You got my note all right then?”

Psmith looked at him, concerned.

“Comrade Windsor,” he said, “what on earth has been happening to you?”

“Oh, that’s all right,” said Billy. “That’s nothing.”

“Nothing! You look as if you had been run over by a motor-car.”

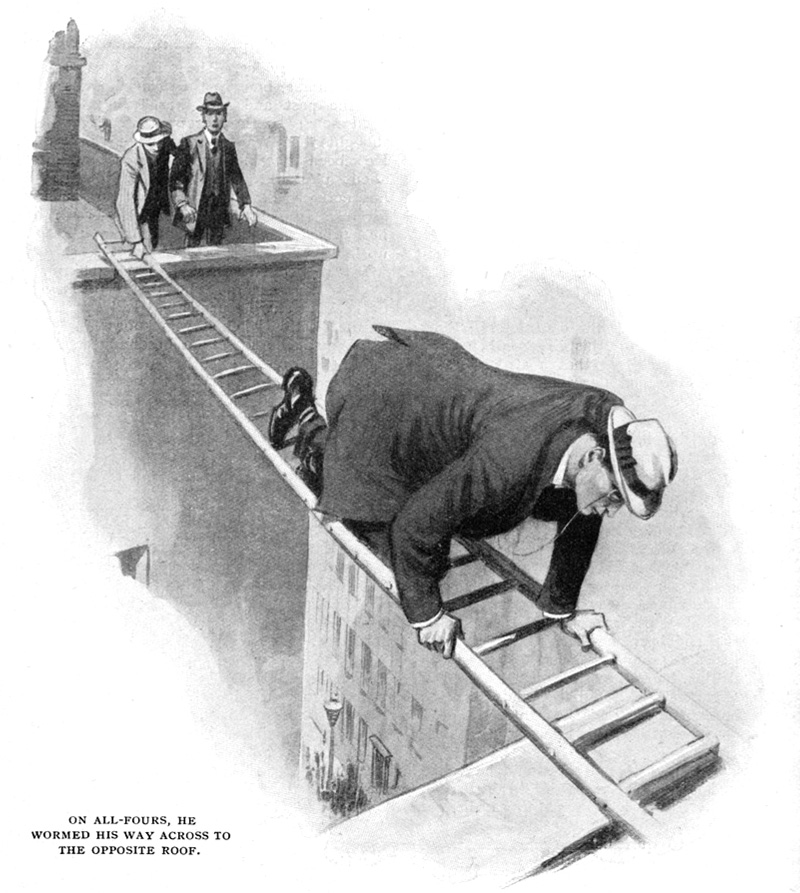

“The cops did that,” said Billy, without any apparent resentment. “They always turn nasty if you put up a fight. I was a fool to do it, I suppose, but I got so mad. They knew perfectly well that I had nothing to do with any pool-room downstairs.”

Psmith’s eye-glass dropped from his eye.

“Pool-room, Comrade Windsor?”

“Yes. The house where I live was raided late last night. It seems that some gamblers have been running a pool-room on the ground floor. Why the cops should have thought I had anything to do with it, when I was sleeping peacefully upstairs, is more than I can understand. Anyway, at about three in the morning there was the dickens of a banging at my door. I got up to see what was doing, and found a couple of policemen there. They told me to come along with them to the station. I asked what on earth for. I might have known it was no use arguing with a New York cop. They said they had been tipped off that there was a pool-room being run in the house, and that they were cleaning up the house, and if I wanted to say anything I’d better say it to the magistrate. I said, all right, I’d put on some clothes and come with them. They said they couldn’t wait about while I put on clothes. I said I wasn’t going to travel about New York in pyjamas, and started to get into my shirt. One of them gave me a shove in the ribs with his night-stick, and told me to come along quick. And that made me so mad I hit out.” A chuckle escaped Billy. “He wasn’t expecting it, and I got him fair. He went down over the bookcase. The other cop took a swipe at me with his club, but by that time I was so mad I’d have taken on Jim Jeffries, if he had shown up and got in my way. I just sailed in, and was beginning to make the man think that he had stumbled on Stanley Ketchel or Kid Brady or a dynamite explosion by mistake, when the other fellow loosed himself from the bookcase, and they started in on me together, and there was a general rough house, in the middle of which somebody seemed to let off about fifty thousand dollars’ worth of fireworks all in a bunch; and I didn’t remember anything more till I found myself in a cell, pretty nearly knocked to pieces. That’s my little life-history. I guess I was a fool to cut loose that way, but I was so mad I didn’t stop to think.”

Psmith sighed.

“You have told me your painful story,” he said. “Now hear mine. After parting with you last night, I went meditatively back to my Fourth Avenue address, and, with a courtly good night to the large policeman who, as I have mentioned in previous conversations, is stationed almost at my very door, I passed on into my room, and had soon sunk into a dreamless slumber. At about three o’clock in the morning I was aroused by a somewhat hefty banging on the door.”

“What!”

“A banging at the door,” repeated Psmith. “There, standing on the mat, were three policemen. From their remarks I gathered that certain bright spirits had been running a gambling establishment in the lower regions of the building—where, I think I told you, there is a saloon—and the Law was now about to clean up the place. Very cordially the honest fellows invited me to go with them. A conveyance, it seemed, waited in the street without. I pointed out, even as you appear to have done, that sea-green pyjamas with old rose frogs were not the costume in which a Shropshire Psmith should be seen abroad in one of the world’s greatest cities; but they assured me—more by their manner than their words—that my misgivings were out of place, so I yielded. These men, I told myself, have lived longer in New York than I. They know what is done and what is not done. I will bow to their views. So I went with them, and after a very pleasant and cosy little ride in the patrol waggon, arrived at the police station. This morning I chatted a while with the courteous magistrate, convinced him by means of arguments and by silent evidence of my open, honest face and unwavering eye that I was not a professional gambler, and came away without a stain on my character.”

Billy Windsor listened to this narrative with growing interest.

“Gum! it’s them!” he cried.

“As Comrade Maloney would say,” said Psmith, “meaning what, Comrade Windsor?”

“Why, the fellows who are after that paper. They tipped the police off about the pool-rooms, knowing that we should be hauled off without having time to take anything with us. I’ll bet anything you like they have been in and searched our rooms by now.”

“As regards yours, Comrade Windsor, I cannot say. But it is an undoubted fact that mine, which I revisited before going to the office, in order to correct what seemed to me even on reflection certain drawbacks to my costume, looks as if two cyclones and a threshing machine had passed through it.”

“They’ve searched it?”

“With a fine-toothed comb. Not one of my objects of vertu but has been displaced.”

Billy Windsor slapped his knee.

“It was lucky you thought of sending that paper by post,” he said. “We should have been done if you hadn’t. But, say,” he went on miserably, “this is awful. Things are just warming up for the final burst, and I’m out of it all.”

“For thirty days,” sighed Psmith. “What Cosy Moments really needs is a sitz-redacteur.”

“A what?”

“A sitz-redacteur, Comrade Windsor, is a gentleman employed by German newspapers with a taste for lèse majesté to go to prison whenever required in place of the real editor. The real editor hints in his bright and snappy editorial, for instance, that the Kaiser’s moustache reminds him of a bad dream. The police force swoops down en masse on the office of the journal, and are met by the sitz-redacteur, who goes with them peaceably, allowing the editor to remain and sketch out plans for his next week’s article on the Crown Prince. We need a sitz-redacteur on Cosy Moments almost as much as a fighting editor; and we have neither.”

“The Kid has had to leave then?”

“He wants to go into training at once. He very sportingly offered to cancel his match, but of course that would never do. Unless you consider Comrade Maloney equal to the job, I must look around me for some one else. I shall be too fully occupied with purely literary matters to be able to deal with chance callers. But I have a scheme.”

“What’s that?”

“It seems to me that we are allowing much excellent material to lie unused in the shape of Comrade Jarvis.”

“Bat Jarvis.”

“The same. The cat-specialist to whom you endeared yourself somewhat earlier in the proceedings by befriending one of his wandering animals. Little deeds of kindness, little acts of love, as you have doubtless heard, help, &c. Should we not give Comrade Jarvis an opportunity of proving the correctness of this statement? I think so. Shortly after you—if you will forgive me for touching on a painful subject—have been haled to your dungeon, I will push round to Comrade Jarvis’ address, and sound him on the subject. Unfortunately, his affection is confined, I fancy, to you. Whether he will consent to put himself out on my behalf remains to be seen. However, there is no harm in trying. If nothing else comes of the visit, I shall at least have had the opportunity of chatting with one of our most prominent citizens.”

A policeman appeared at the door.

“Say, pal,” he remarked to Psmith, “You’ll have to be fading away soon, I guess. Give you three minutes more. Say it quick.”

He retired. Billy leaned forward to Psmith.

“I guess they won’t give me much chance,” he whispered, “but if you see me around in the next day or two, don’t be surprised.”

“I fail to follow you, Comrade Windsor.”

“Men have escaped from Blackwell’s Island before now. Not many, it’s true; but it has been done.”

Psmith shook his head.

“I shouldn’t,” he said. “They’re bound to catch you, and then you will be immersed in the soup beyond hope of recovery. I shouldn’t wonder if they put you in your little cell for a year or so.”

“I don’t care,” said Billy stoutly. “I’d give a year later on to be round and about now.”

“I shouldn’t,” urged Psmith. “All will be well with the paper. You have left a good man at the helm.”

“I guess I shan’t get a chance, but I’ll try it if I do.”

The door opened and the policeman reappeared.

“Time’s up, I reckon.”

“Well, good-bye, Comrade Windsor,” said Psmith regretfully. “Abstain from undue worrying. It’s a walk-over from now on, and there’s no earthly need for you to be around the office. Once, I admit, this could not have been said. But now things have simplified themselves. Have no fear. This act is going to be a scream from start to finish.”

CHAPTER XXIV.

a gathering of cat-specialists.

ASTER MALONEY raised his eyes for a moment

from his book as Psmith re-entered the office.

ASTER MALONEY raised his eyes for a moment

from his book as Psmith re-entered the office.

“Dere’s a guy in dere waitin’ ter see youse,” he said briefly, jerking his head in the direction of the inner room.

“A guy waiting to see me, Comrade Maloney? With or without a sand-bag?”

“Says his name’s Jackson,” said Master Maloney, turning a page.

Psmith moved quickly to the door of the inner room.

“Why, Comrade Jackson,” he said, with the air of a father welcoming home the prodigal son, “this is the maddest, merriest day of all the glad New Year. Where did you come from?”

Mike, looking very brown and in excellent condition, put down the paper he was reading.

“Hullo, Psmith,” he said. “I got back this morning. We’re playing a game over in Brooklyn to-morrow.”

“No engagements of any importance to-day?”

“Not a thing. Why?”

“Because I propose to take you to visit Comrade Jarvis, whom you will doubtless remember.”

“Jarvis?” said Mike, puzzled. “I don’t remember any Jarvis.”

“Let your mind wander back a little through the jungle of the past. Do you recollect paying a visit to Comrade Windsor’s room——”

“By the way, where is Windsor?”

“In prison. Well, on that evening——”

“In prison?”

“For thirty days. For slugging a policeman. More of this, however, anon. Let us return to that evening. Don’t you remember a certain gentleman with just about enough forehead to keep his front hair from getting all tangled up with his eyebrows——”

“Oh, the cat chap? I know.”

“As you very justly observe, Comrade Jackson, the cat chap. For going straight to the mark and seizing on the salient point of a situation, I know of no one who can last two minutes against you. Comrade Jarvis may have other sides to his character—possibly many—but it is as a cat chap that I wish to approach him to-day.”

“What’s the idea? What are you going to see him for?”

“We,” corrected Psmith. “I will explain all at a little luncheon at which I trust that you will be my guest. Already, such is the stress of this journalistic life, I hear my tissues crying out imperatively to be restored. An oyster and a glass of milk somewhere round the corner, Comrade Jackson? I think so, I think so.”

“I was reading Cosy Moments in there,” said Mike, as they lunched. “You certainly seem to have bucked it up rather. Kid Brady’s reminiscences are hot stuff.”

“Somewhat sizzling, Comrade Jackson,” admitted Psmith. “They have, however, unfortunately cost us a fighting editor.”

“How’s that?”

“Such is the boost we have given Comrade Brady, that he is now never without a match. He has had to leave us to-day to go to White Plains to train for an encounter with a certain Mr. Wood, a four-ounce-glove juggler of established fame.”

“I expect you need a fighting-editor, don’t you?”

“He is indispensable, Comrade Jackson, indispensable.”

“No rotting. Has anybody cut up rough about the stuff you’ve printed?”

“Cut up rough? Gadzooks! I need merely say that one critical reader put a bullet through my hat——”

“Rot! Not really?”

“While others kept me tree’d on top of a roof for the space of nearly an hour. Assuredly they have cut up rough, Comrade Jackson.”

“Great Scott! Tell us.”

Psmith briefly recounted the adventures of the past few weeks.

“But, man,” said Mike, when he had finished, “why on earth don’t you call in the police?”

“We have mentioned the matter to certain of the force. They appeared tolerably interested, but showed no tendency to leap excitedly to our assistance. The New York policeman, Comrade Jackson, like all great men, is somewhat peculiar. If you go to a New York policeman and exhibit a black eye, he will examine it and express some admiration for the abilities of the citizen responsible for the same. If you press the matter, he becomes bored, and says, ‘Ain’t youse satisfied with what youse got? G’wan!’ His advice in such cases is good, and should be followed. No; since coming to this city I have developed a habit of taking care of myself, or employing private help. That is why I should like you, if you will, to come with me to call upon Comrade Jarvis. He is a person of considerable influence among that section of the populace which is endeavouring to smash in our occiputs. Indeed, I know of nobody who cuts a greater quantity of ice. If I can only enlist Comrade Jarvis’s assistance, all will be well. If you are through with your refreshment, shall we be moving in his direction? By the way, it will probably be necessary in the course of our interview to allude to you as one of our most eminent living cat-fanciers. You do not object? Remember that you have in your English home seventy-four fine cats, mostly Angoras. Are you on to that? Then let us be going. Comrade Maloney has given me the address. It is a goodish step down on the East side. I should like to take a taxi, but it might seem ostentatious. Let us walk.”

They found Mr. Jarvis in his Groome Street fancier’s shop, engaged in the intellectual occupation of greasing a cat’s paws with butter. He looked up as they entered, and began to breathe a melody with a certain coyness.

“Comrade Jarvis,” said Psmith, “we meet again. You remember me?”

“Nope,” said Mr. Jarvis, pausing for a moment in the middle of a bar, and then taking up the air where he had left off. Psmith was not discouraged.

“Ah,” he said tolerantly, “the fierce rush of New York life! How it wipes from the retina to-day the image impressed on it but yesterday. Are you with me, Comrade Jarvis?”

The cat-expert concentrated himself on the cat’s paws without replying.

“A fine animal,” said Psmith, adjusting his eyeglass. “To which particular family of the Felis Domestica does that belong? In colour it resembles a Neapolitan ice more than anything.”

Mr. Jarvis’s manner became unfriendly.

“Say, what do youse want? That’s straight, ain’t it? If youse want to buy a boid or a snake why don’t youse say so?”

“I stand corrected,” said Psmith. “I should have remembered that time is money. I called in here partly on the strength of being a colleague and side-partner of Comrade Windsor——”

“Mr. Windsor! De gent what caught my cat?”

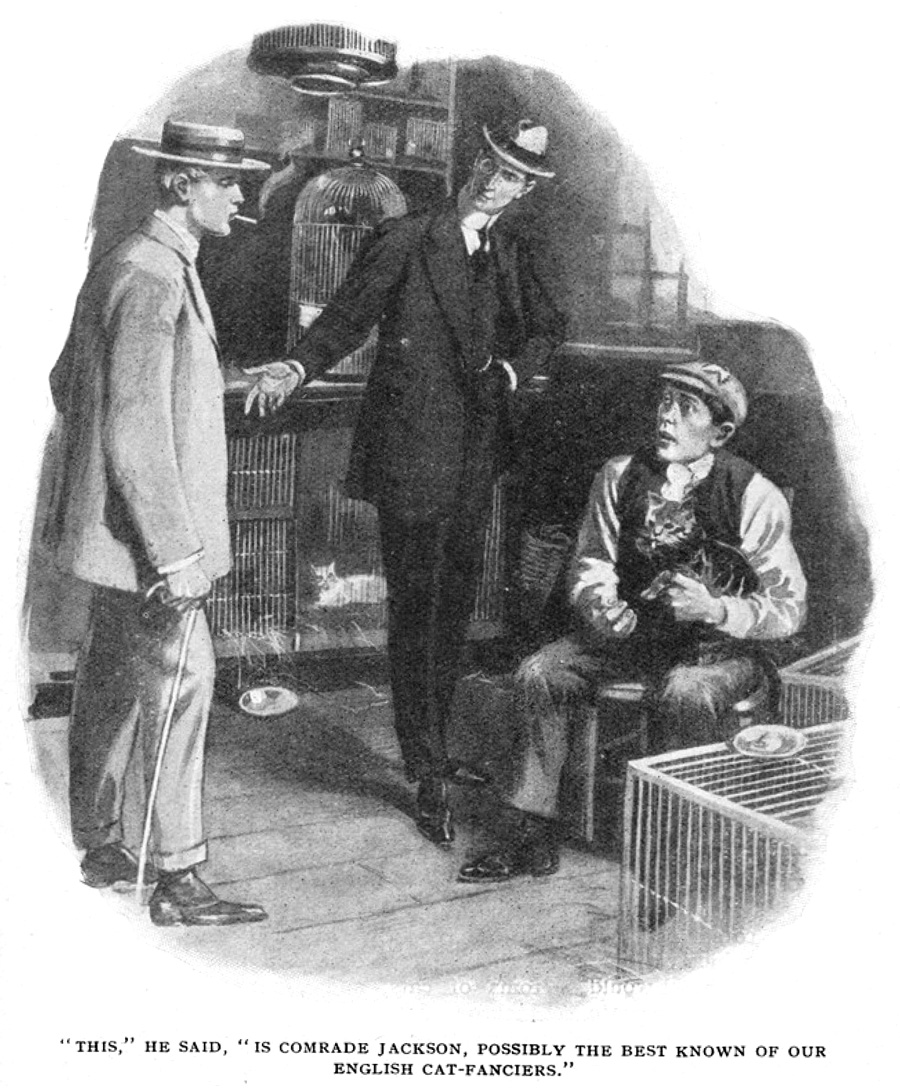

“The same—and partly in order that I might make two very eminent cat-fanciers acquainted. This,” he said, with a wave of his hand in the direction of the silently protesting Mike, “is Comrade Jackson, possibly the best known of our English cat-fanciers. Comrade Jackson’s stud of Angoras is celebrated wherever the King’s English is spoken, and in Hoxton.”

Mr. Jarvis rose, and, having inspected Mike with silent admiration for a while, extended a well-buttered hand towards him. Psmith looked on benevolently.

“What Comrade Jackson does not know about cats,” he said, “is not knowledge. His information on Angoras alone would fill a volume.”

“Say,”—Mr. Jarvis was evidently touching on a point which had weighed deeply upon him—“why’s catnip called catnip?”

Mike looked at Psmith helplessly. It sounded like a riddle, but it was obvious that Mr. Jarvis’ motive in putting the question was not frivolous. He really wished to know.

“The word, as Comrade Jackson was just about to observe,” said Psmith, “is a corruption of cat-mint. Why it should be so corrupted I do not know. But what of that? The subject is too deep to be gone fully into at the moment. I should recommend you to read Comrade Jackson’s little brochure on the matter. Passing lightly on from that——”

“Did youse ever have a cat dat ate beetles?” inquired Mr. Jarvis.

“There was a time when many of Comrade Jackson’s felidæ supported life almost entirely on beetles.”

“Did they git thin?”

Mike felt that it was time, if he was to preserve his reputation, to assert himself.

“No,” he replied firmly.

Mr. Jarvis looked astonished.

“English beetles,” said Psmith, “don’t make cats thin. Passing lightly——”

“I had a cat oncest,” said Mr. Jarvis, ignoring the remark and sticking to his point, “dat ate beetles and got thin and used to tie itself inter knots.”

“A versatile animal,” agreed Psmith.

“Say,” Mr. Jarvis went on, now plainly on a subject near to his heart, “dem beetles is fierce. Sure. Can’t keep de cats off of eatin’ dem, I can’t. First t’ing you know dey’ve swallowed dem, and den dey gits thin and ties theirselves into knots.”

“You should put them into strait-waistcoats,” said Psmith. “Passing, however, lightly——”

“Say, ever have a cross-eyed cat?”

“Comrade Jackson’s cats,” said Psmith, “have happily been almost free from strabismus.”

“Dey’s lucky, cross-eyed cats is. You has a cross-eyed cat, and not’in’ don’t never go wrong. But, say, was dere ever a cat wit one blue eye and one yaller one in your bunch? Gum, it’s fierce when it’s like dat. It’s a real skiddoo, is a cat wit one blue eye and one yaller one. Puts you in bad, surest t’ing you know. Oncest a guy give me a cat like dat, and first t’ing you know I’m in bad all round. It wasn’t till I give him away to de cop on de corner and gets me one dat’s cross-eyed dat I lifts de skiddoo off of me.”

“And what happened to the cop?” inquired Psmith, interested.

“Oh, he got in bad, sure enough,” said Mr. Jarvis without emotion. “One of de boys what he’d pinched and had sent to de Island once lays for him and puts one over him wit a black-jack. Sure. Dat’s what comes of havin’ a cat wit one blue eye and one yaller one.”

Mr. Jarvis relapsed into silence. He seemed to be meditating on the inscrutable workings of Fate. Psmith took advantage of the pause to leave the cat topic and touch on matters of more vital import.

“Tense and exhilarating as is this discussion of the optical peculiarities of cats,” he said, “there is another matter on which, if you will permit me, I should like to touch. I would hesitate to bore you with my own private troubles, but this is a matter which concerns Comrade Windsor as well as myself, and I know that your regard for Comrade Windsor is almost an obsession.”

“How’s that?”

“I should say,” said Psmith, “that Comrade Windsor is a man to whom you give the glad hand.”

“Sure. He’s to the good, Mr. Windsor is. He caught me cat.”

“He did. By the way, was that the one that used to tie itself into knots?”

“Nope. Dat was anudder.”

“Ah! However, to resume. The fact is, Comrade Jarvis, we are much persecuted by scoundrels. How sad it is in this world! We look to every side. We look north, east, south, and west, and what do we see? Mainly scoundrels. I fancy you have heard a little about our troubles before this. In fact, I gather that the same scoundrels actually approached you with a view to engaging your services to do us in, but that you very handsomely refused the contract.”

“Sure,” said Mr. Jarvis, dimly comprehending. “A guy comes to me and says he wants you and Mr. Windsor put through it, but I gives him de t’run down. ‘Nuttin’ done,’ I says. ‘Mr. Windsor caught me cat.’”

“So I was informed,” said Psmith. “Well, failing you, they went to a gentleman of the name of Reilly.”

“Spider Reilly?”

“You have hit it, Comrade Jarvis. Spider Reilly, the lessee and manager of the Three Points gang.”

“Dose T’ree Points, dey’re to de bad. Dey’re fresh.”

“It is too true, Comrade Jarvis.”

“Say,” went on Mr. Jarvis, waxing wrathful at the recollection, “what do youse t’ink dem fresh stiffs done de udder night? Started some rough woik in me own dance-joint.”

“Shamrock Hall?” said Psmith.

“Dat’s right. Shamrock Hall. Got gay, dey did, wit some of de Table Hillers. Say, I got it in for dem gazebos, sure I have. Surest t’ing you know.”

Psmith beamed approval.

“That,” he said, “is the right spirit. Nothing could be more admirable. We are bound together by our common desire to check the ever-growing spirit of freshness among the members of the Three Points. Add to that the fact that we are united by a sympathetic knowledge of the manners and customs of cats, and especially that Comrade Jackson, England’s greatest fancier, is our mutual friend, and what more do we want? Nothing.”

“Mr. Jackson’s to de good,” assented Mr. Jarvis, eyeing Mike in friendly fashion.

“We are all to de good,” said Psmith. “Now the thing I wished to ask you is this. The office of the paper on which I work was until this morning securely guarded by Comrade Brady, whose name will be familiar to you.”

“De Kid?”

“On the bull’s-eye, as usual, Comrade Jarvis. Kid Brady, the coming light-weight champion of the world. Well, he has unfortunately been compelled to leave us, and the way into the office is consequently clear to any sand-bag specialist who cares to wander in. Matters connected with the paper have become so poignant during the last few days that an inrush of these same specialists is almost a certainty, unless—and this is where you come in.”

“Me?”

“Will you take Comrade Brady’s place for a few days?”

“How’s that?”

“Will you come in and sit in the office for the next day or so and help hold the fort? I may mention that there is money attached to the job. We will pay for your services. How do we go, Comrade Jarvis?”

Mr. Jarvis reflected but a brief moment.

“Why, sure,” he said. “Me fer dat. When do I start?”

“Excellent, Comrade Jarvis. Nothing could be better. I am obliged. I rather fancy that the gay band of Three Pointers who will undoubtedly visit the offices of Cosy Moments in the next few days, probably to-morrow, are due to run up against the surprise of their lives. Could you be there at ten to-morrow morning?”

“Sure t’ing. I’ll bring me canister.”

“I should,” said Psmith. “In certain circumstances one canister is worth a flood of rhetoric. Till to-morrow, then, Comrade Jarvis. I am very much obliged to you.”

“Not at all a bad hour’s work,” said Psmith complacently, as they turned out of Groome Street. “A vote of thanks to you, Comrade Jackson, for your invaluable assistance.”

“It strikes me I didn’t do much,” said Mike with a grin.

“Apparently, no. In reality, yes. Your manner was exactly right. Reserved, yet not haughty. Just what an eminent cat-fancier’s manner should be. I could see that you made a pronounced hit with Comrade Jarvis. By the way, if you are going to show up at the office to-morrow, perhaps it would be as well if you were to look up a few facts bearing on the feline world. There is no knowing what thirst for information a night’s rest may not give Comrade Jarvis. I do not presume to dictate, but if you were to make yourself a thorough master of the subject of catnip, for instance, it might quite possibly come in useful.”

(To be concluded)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums