CHAPTER I.

The Mumps and a Tragedy.

IT is not always pleasant to have the mumps. There are several drawbacks to the malady. It can be painful, and it does not tend to improve one’s personal appearance. But it has this great advantage, that, if it attacks you towards the end of the holidays, you are pretty certain to be enjoying yourself at home when the rest of the world has gone back to school.

This was the case with Jimmy Stewart. After six weeks of the best time imaginable, he had been informed by the doctor, just when the prospect of school was beginning to lose the vagueness which had surrounded it during August and the early part of September, that he had got the mumps, and would be unable to return to Marleigh for another three weeks. Jimmy had danced a cake-walk as a feeble attempt to do justice to his feelings.

It was not that he disliked Marleigh. As a school he was very fond of it. Still, there was no getting out of the fact that it was a school; and, with the weather as glorious as it was, Jimmy did not want any school.

So he went into quarantine with a light heart. The chief drawback to mumps—the fact that one is cut off from the society of one’s fellows—did not worry Jimmy. He was a sociable youth in term-time, and had as many friends as anybody else in the school; but in the holidays he found his own company good enough for him. He liked to loaf about by himself by the river, reading and ratting and fishing, and mumps made no difference to this programme. His father, Colonel Stewart, of the Indian Army, had been big-game shooting in Africa for the last nine months, and when his father was away he never saw anybody to speak of during the holidays, except the servants.

So Jimmy with the mumps carried on much as he had done before he got the mumps. The weather kept fine, and he spent most of his time down by the river.

It was now the last evening of his extra holidays. The doctor, to his disgust, had been up that morning, and pronounced him free from infection.

“You can go back to your school to-morrow,” he said.

“Wouldn’t it be better if I took another day or two?” suggested Jimmy. “It would be rather sickening for the chaps at Marleigh if I spread mumps there.”

“You’re too unselfish, my lad,” said Doctor Willis. “We mustn’t have you depriving yourself of school for their sake. Back you go tomorrow by the first train!”

“Oh, dash,” said Jimmy.

“Just so,” said Doctor Willis.

Jimmy had spent his last evening in one long, last bathe in the pool below the mill. It was getting on for October, but the water was still warm; and Jimmy had splashed about for an hour. He was now lying on the bank, reading.

A shadow fell across his book. He looked up. A sturdy, brown-faced man was standing beside him. It was his brownness which struck Jimmy most in his appearance. He was more sunburnt than anyone he had seen, with the exception of his father. The Indian sun had tanned Colonel Stewart to the colour of walnut, and this man had the same dried-up look.

“Well, matey,” said the man.

“Hullo,” said Jimmy.

“Taking a spell off?”

“Yes.”

“Love us, it does a man good to see all this green. There’s nothing to beat the good old English country. When you’ve been in India for half a dozen years——”

“I thought you came from India,” said Jimmy.

“The sun there ain’t what you’d call a patent complexion cream, love us if it is. Do you live in these parts?”

“In the holidays I do.”

“Then perhaps you could tell me where a house by the name of Gorton Hall is. G-o-r-t-o-n. That’s the place.”

Gorton Hall was Colonel Stewart’s house. Jimmy wondered for a moment what the man might want there, but he supposed he must be a friend of one of the servants. In Colonel Stewart’s absence the servants had developed a habit of entertaining to a certain extent. Friends from the village were always dropping in.

“It’s straight on down the road at the end of this field. You could get to it by a short cut, but you’d probably miss your way. Better stick to the road. You go by the church, pass a public-house——”

“Do I!” said the other. “Not if I know it. Not with a thirst like what I’ve got. Five minutes one way or the other won’t make much difference to me now. So long, matey. Be good.”

“So long,” said Jimmy, returning to his book.

He read on for another hour and more, till the sun disappeared behind the mill, and a chilly mist from the river reminded him that it was not midsummer, when you could sit out of doors half the night. There was very little fun in sitting there, shivering; so Jimmy got up, and began to walk back to the house across the fields.

It was dusk by the time he got into the drive. Everything looked dim and mysterious. The book Jimmy had been reading had been of a sensational type, and he could not keep down that vague feeling that someone was looking at him from behind his back, and following him, which most people have experienced at one time or another. He stopped now and then to listen, but he could hear nothing. He walked on quickly up the drive towards the house, where the lighted windows gleamed cheerfully.

Suddenly his heart leaped. A few feet in front of him a man’s figure seemed to have appeared from nowhere. Jimmy stood still. Then he saw that the man was walking away from him, and a moment later he had recognised his friend of the riverside, the man from India.

“Rummy I didn’t see him before,” thought Jimmy. “I suppose the mist must have thinned.”

He hurried on to overtake the man. He was feeling that it would not be unpleasant to have company for what remained of the walk to the house. He broke into a trot.

The behaviour of the man in front was singular. He whipped round at the sound of footsteps, and when Jimmy arrived he found himself looking into the muzzle of a small black revolver.

The next moment the man had recognised him.

“Hullo, matey,” he said. “It’s you, is it? Thought it might be someone else. Excuse the gun, sonny. You get jumpy out where I’ve been, and you find it’s best to get into the habit of being ready to shoot first, and challenge afterwards. But we’re chums, we are. And what might you be after? What do you want at Colonel Stewart’s house?”

“I live there,” said Jimmy, with a laugh. “I’m his son, you know.”

The man looked at him with interest.

“His nipper, are you?” he said. “Well, I expect you’ll do him credit. He’s a fine officer, the colonel. Served under him in the North Surreys up on the frontier before I exchanged. He’ll be in one of those rooms, I reckon,” he added, pointing to the lighted windows, “dressing for mess.”

“Oh, no,” said Jimmy. “Didn’t you know? Father’s not in England.”

“Not in England!”

The man looked dazed, almost as if he had received a blow.

“No. He’s been out in Africa, shooting big game, for months. No one knows when he’ll be back. I haven’t had a letter from him for ages. He’s not very good at writing. For all I know, he may be on his way back now.”

The man continued to stand staring blankly at him. It began to dawn on Jimmy at last that Colonel Stewart’s absence was something that mattered more than a little.

“I’m awfully sorry,” he said. “Had you to see him about something important?”

The man had opened his mouth to reply, when suddenly something hummed past Jimmy’s ear like an angry wasp. The man from India reeled, staggered back, groping blindly with his hands, and fell in a heap.

CHAPTER II.

The Man from India—A Face in the Night.

The suddenness of the thing paralysed Jimmy for the moment. It was all like a nightmare. He could not realise it. He had heard no report; he had seen no one. Yet there was the man on the ground, while a thin, dark stream trickled slowly over the gravel of the drive.

Then he found his voice and regained the use of his limbs simultaneously. He ran, shouting, towards the house.

As he reached it, the front door opened, throwing a flood of light out into the mist.

“Who’s that? What’s the matter? Lord, Master Jimmy, is that you?”

It was Perks, the colonel’s butler.

“Perks, there’s a man been shot in the drive.”

Perks’s was one of those minds which work slowly.

“Who shot him?” he inquired.

“I don’t know. It all happened in a second. I was standing talking to him, when he went down in a heap. I heard the bullet. It whizzed close to my ear. But I didn’t hear any shot. Come and help carry him in.”

“Is he dead, Master Jimmy?”

“I don’t know. He looks jolly beastly.”

“I’ll fetch George to help.”

Perks was beginning to feel uneasy about the affair. His had been a placid life up till now, and, if he had to roam about while assassins were in the offing, he felt that it would be just as well to have George, the groom, a man of muscle, by his side.

“Someone ought to fetch the doctor, Master Jimmy.”

Jimmy had a struggle with himself. He would have liked, above all things, to have stayed in the house, where everything was bright and lit-up and safe, instead of venturing out again into the darkness; but he told himself that it must be done, and he was the one who could do it quickest.

“I’ll go,” he said. “You bring the man in.”

He found his bicycle, and lifted it down the steps on to the drive. As he did so, George the groom appeared with Perks, carrying the board which was to act as a stretcher. They proceeded down the drive to where the man was lying, a vague shape in the darkness. Jimmy lit his lamp, and mounted. He slowed down as he reached the wounded man.

“How is he?” he asked.

George the groom touched his forelock.

“He ain’t dead, Master Jimmy, but he’s next door to it. If I was you I’d fetch the doctor quick.”

Jimmy rode on, looking neither to right nor left. He was conscious of a feeling as if a cold hand had been laid on the pit of his stomach, and his scalp was tingling. He had felt the same sensations before, in a slighter degree, on going in to bat for the school in an important match. If he had had to describe his feelings, he would have said that he was in a blue funk.

Once out of the drive and in the road, he felt better. It was not a long ride to the doctor’s house. He propped his bicycle against the wall, and rang the bell. The doctor was in. Jimmy was shown into the consulting-room, and presently Doctor Willis entered, in cricket flannels, a Norfolk jacket, and carpet slippers, smoking a pipe.

“Well, young man,” he said, “what do you mean by coming breaking in on an overworked medical man’s hard-earned leisure? Have you come to tell me you’ve developed some other fatal malady which will keep you away from school?”

“I say, can you come up to the house at once? A man’s been shot.”

“Been shot!”

“Yes. In our drive.”

“How did it happen?”

“I don’t know. I was standing, talking to him, when the bullet came from nowhere, and hit him.”

“How do you mean—from nowhere? Didn’t you hear a report?”

“No. That’s the rummy part of it.”

“Where is he shot?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t stop to look. I rushed to the house to get help, and then came straight to you. Can you see him now?”

“I’ll get my bicycle. Wait a moment.”

The moment seemed hours, but he reappeared at last, wheeling a bicycle and carrying a small bag.

“Now then,” he said.

They rode off together.

Perks was waiting at the door with the information that the wounded man had been placed on the sofa in the colonel’s sitting-room.

“You wait here, young man,” said Doctor Willis.

Jimmy sat down, and tried to interest himself in a book, but his brain was in a whirl, and he could not fix his attention on the print.

Presently he heard the sound of returning footsteps. Dr. Willis came in, looking grave.

“It’s been a nasty job,” he said. “I’ve got it out, though.”

He held up a small piece of lead.

“Where was he hit?”

“In the left shoulder. An inch or two lower, and it would have been through his heart. Your friend has had a narrow escape. Who is he?”

“I don’t know.”

“Don’t know? He seems to know you. He’s asking to see you.”

“I told him who I was. He’d come to see father. He’d served under him in India. I believe it was something important he wanted to see him about. At any rate, he looked jolly sick when I said father was away, and nobody knew when he’d be back.”

“Well, he wants to see you about something, and pretty badly too. He wouldn’t tell me what it was. Said he must see you. ‘Send the colonel’s nipper here,’ he kept saying.”

“I’d better go at once, hadn’t I?”

Doctor Willis looked thoughtful.

“Strictly speaking,” he said, “he isn’t in a condition to see anyone. But he seems set on it, and it’ll be worse for him if he worries. I’ve told him you’ll be with him in a few minutes. This is a confoundedly mysterious affair, young man. I can’t make it out. He seems to take it quite as a matter of course that he should have been shot through the shoulder with an air-gun in the drive of an English house. Yes, an air-gun. Not the sort you use. Something a great deal bigger and more dangerous. I should like to find the owner of that gun, and ask him one or two questions. There’s too much mystery about this business to please me. Well, you’d better go and see him. You must not let him keep you long. He’s very weak indeed. I shall give you a quarter of an hour; then out you’ll have to come, whether he’s told you what he wants to or not. Run along.”

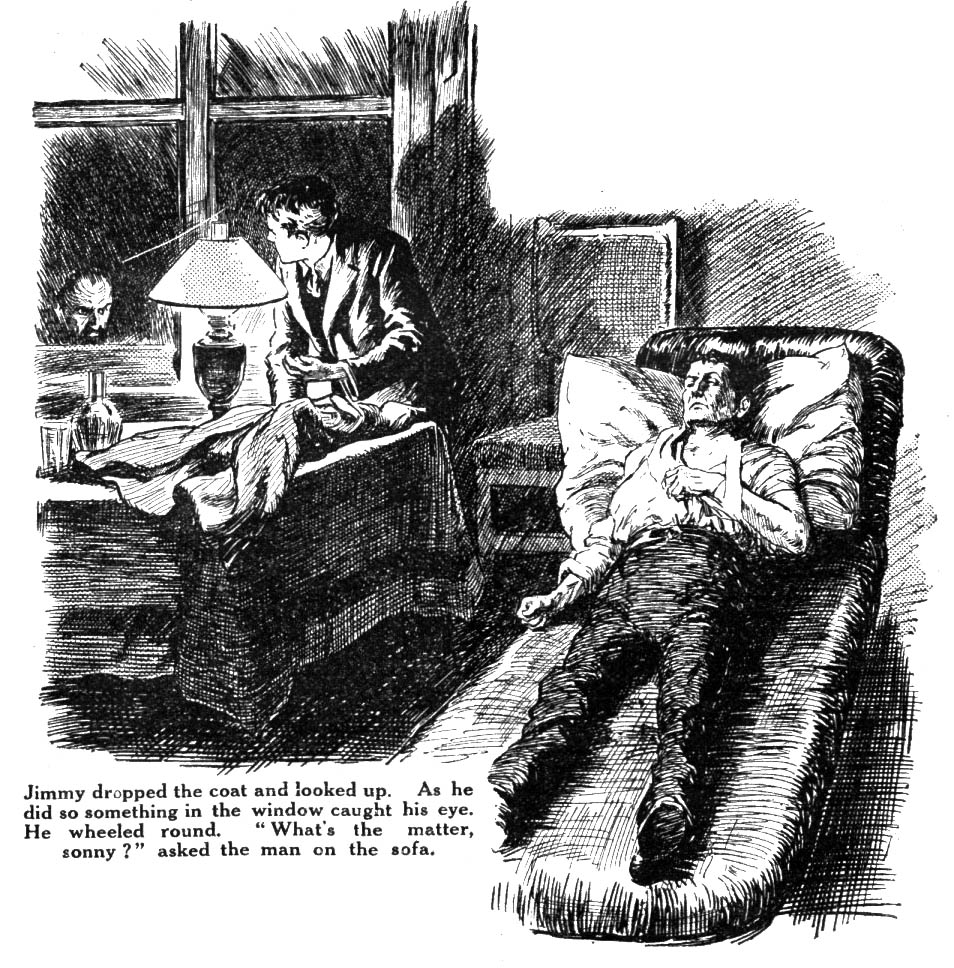

Jimmy made his way to the sitting-room. The man was lying on the sofa, with his coat off and half his shirt cut away. His left shoulder was a mass of bandages. A shaded lamp burned on the table.

“Hullo,” said Jimmy awkwardly. The atmosphere of a sick-room always made him feel awkward.

“Well, sonny,” whispered the man. His voice was painfully weak, and the brown of his face had changed to a light yellow. “Here! Pull that blind down.”

Jimmy looked at the window.

“There isn’t one,” he said. A dislike of blinds was one of Colonel Stewart’s fads. He detested anything that gave him a shut-in feeling.

“Never mind. I expect they’d be afraid to risk it.”

“Was there anything you wanted to tell me?” said Jimmy. “The doctor says he’ll only give us a quarter of an hour.”

“I won’t waste time. I tell you, it gave me a bad shock when you told me the colonel wasn’t at home. Worse shock than that bloomin’ bullet did, ’cos I was expecting that, and I wasn’t expecting the other.”

“You were expecting it!”

“Yes, or something of the same sort. Do you know how many miles I’ve come to see the colonel, sonny?”

“No.”

“No more do I. Thousands. And to find he wasn’t on the spot when I got here. I tell you, it didn’t want a bullet to knock me over then. A feather would have done it easy.”

“But how do you mean you were expecting it?”

“Because it’s happened before. I’ve heard the whistle of those bullets half a dozen times, I have, since I left the Dâk Bungalow. Heard ’em zipping past my ears for all the world like blanked mosquitoes in the ’ot weather. The day I left India one of ’em lifted the ’at off my head as if it was a breath of wind. It’s like my luck that they should get me when I was thinking I was safe home. Pipped on the post, I call it.”

“Who are they?” whispered Jimmy.

“Never you mind, sonny. No one you’d know. I’m not sure I know myself, though I can make a pretty fair guess. They’re modest, retiring coves, they are. Don’t shove themselves forward. Would rather you didn’t make a fuss over them, if it’s all the same to you. Oh, they’re beauties. I wish I could get within arm’s reach of them. They’d get one of those unsolicited testimonials the papers are always writing about.”

His voice died away.

“Got a sip of water about, sonny?” he whispered.

There was a jug and a glass on the table. Jimmy poured out a glassful. He drank it greedily.

“Ah!” he grinned; “there’s a deal to be said for water, after all, though I was never one to take it at the canteen. Now, sonny, time’s getting on. The doctor’ll be coming in presently. I’ll tell you what it is I wanted to say to you. Just fetch that coat there, will you? Got it? That’s right. Now feel along the right sleeve. Inside. Ah! Feel anything?”

“There’s a sort of hard lump.”

“Right you are, matey. There is a sort of hard lump. Now just you turn that sleeve inside out. Got a knife? Right. Cut the lining, and let’s see what we’ve got.”

Jimmy did as he was directed. Something small and round dropped out into his hand. He looked at it curiously in the lamplight. It was a dull, dirty blue stone. One side of it was half covered with a piece of brown paper, the other with some curious scratches, arranged with a certain order that suggested that they might be letters of some alphabet which was unknown to him. The stone was about the size of a shilling, perhaps a little larger; and it looked like nothing more than a piece of blue sealing-wax which had half-melted, and, while in that condition, had got things stuck on to it.

Jimmy dropped the coat, and looked up. As he did so, something in the window caught the corner of his eye. He wheeled round.

A man’s face was looking through into the room.

For a second Jimmy met his eyes. Then the face disappeared. He rushed to the window. There was nothing to be seen. The whole thing might have been a trick of the imagination, so suddenly had it vanished. But Jimmy knew that his imagination had played him no trick. He had seen a man’s face, a striking face, with piercing, cruel eyes. The lower half had been covered by a beard. He paused irresolutely.

“What’s the matter, sonny?” asked the man on the sofa.

(To be continued next week.)

Note:

The British shilling coin was 23.6 mm in diameter, about 0.93 inches. For comparison, the USA quarter dollar coin is 0.955 inches in diameter (about 24.3 mm).

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums