CHAPTER III.

The Blue Stone.

JIMMY pulled himself together. He remembered what Dr. Willis had said about his patient’s weak state. It was no good exciting him by telling him what he had seen. In his present state it might be dangerous.

“It’s nothing,” he said; “I only thought I heard something.”

The man sank back again on the sofa.

“They wouldn’t risk coming so close to the house, not after what’s happened,” he said. “I expect it was nothing. Got the stone, matey?”

“Here you are,” said Jimmy, dropping it into his hand. The man looked at it in silence.

“Well,” he said at last, “it ain’t much of a thing, not to look at, is it? But it’s a deal more important than it looks, that dirty little bit of blue glass is. It’s cost a good few poor chaps their lives in its time, not forgetting a few narrow squeaks to Corporal Sam Burrows, which is me, matey. And too bloomin’ nearly the late Corporal Sam Burrows for my taste. It’s cruel hard luck, strike me if it ain’t, not finding the colonel here to take this bit of blue misery off my hands. See here, sonny. Listen to me. You’re a good plucked one. I can see that. You’re the colonel’s nipper, and you do him credit. Are you game to tackle what may turn out a nasty job?”

“What is it?”

“It’s like this. There’s certain parties what is most uncommonly anxious, as you see, to lay their hands on this stone. And there’s certain other parties, what may be the Government of India or may not—I’m not telling you anything, mind—what’s equally bloomin’ anxious to keep it out of their hands till they can slip it over to the colonel, who’ll know what to do with it. See? Well, it’s like this. It’s no good me keeping the thing. They know where I am, and they’d have it in a couple o’ days. But if you was to take it off to school with you, ’ow are they to know? They sees you going back to school, same as any other young gentleman. ’Ow are they to know you’ve got the blue ruin in your trousers’ pocket? Though, mind you, there’s always the risk. You’ve got to think of that. If these parties I’m talking about once got to know as how you’d got it, they’d be down on you like a swarm of bees. And bees with bloomin’ A1 stings, too.”

Jimmy was silent. Things seemed to be happening to him so rapidly that everything had become unreal. Nothing sensational had ever occurred to him before in his whole life. His mind could only grasp one thing clearly, and that was that it was of the utmost importance that this small blue stone should be kept hidden till the return of Colonel Stewart. As for the risk—he could not forget the face that had looked into the room. Whoever had been at the window had seen him with the stone in his hands.

“Well, sonny?” said Sam Burrows.

The Stewarts, father and son, did not belong to the type which weighs every risk and chance of an adventure before embarking on it. They were accustomed to act first, and reckon up the danger afterwards. Colonel Stewart had won the D.S.O. for capturing a position which, according to all the rules of warfare, could not have been captured with the force at his disposal; and Jimmy took after his father.

“All right,” he said. “Give us it.”

“You are the colonel’s nipper,” said Sam, with conviction. “Here’s the stone, sonny. Don’t let it out of your hands for a minute. And keep your eyes skinned. Maybe there won’t be any trouble at all, but if they do find out as you’ve got it—— I wish I could tell you who to watch out for, but I bloomin’ well don’t know myself. I only ’eard their blanked bullets. I can tell you one thing, though. If you should see a brown man with a twisted leg hanging about, keep your eyes open, and don’t go for walks without ’avin’ a chum or two with you. He’s the only one of the lot as I could swear to, and I don’t know if he’s in England. I ’ad dealings with him in India frequent, but whether he stopped there or not I couldn’t tell you. I know I haven’t set eyes on him this side. Hullo, here’s the doctor come to tell you it’s time for us to part.”

“You’re perfectly right,” said Doctor Willis, taking Jimmy by the shoulder, and pushing him towards the door. “There are your marching orders, young man; and if I catch you in here again, I’ll give you the stiffest black draught you ever had.”

CHAPTER IV.

The Thief in the Night and a Journey by Train.

Jimmy did not sleep much that night. The excitement by itself would have kept him awake. Added to the responsibility of having the blue stone in his possession, it effectually put an end to any hopes he might have had of dropping off. After lying in the dark for an hour or so, he lit the gas, and began to read. It was a slow business, and after a while he found it a hungry one. At about three o’clock he was feeling that, if he did not get something to eat at once, exhausted Nature would be able to hold out no longer. He slipped on a coat and a pair of shoes, and stole out.

He had been on these nocturnal expeditions before, both at home and at school, where he and his friend, Tommy Armstrong, made rather a habit of wandering by night. He knew that the silence was the chief thing that made for success, even at home, for Perks had a rooted objection to having his stores raided, and Perks, when offended, could make himself thoroughly objectionable.

So Jimmy crept quietly along till he reached the larder door. It was only secured by a bolt outside. He went in, and was rummaging about with the aid of a match when he heard a sound.

He blew out the match and listened intently. He had not been mistaken. Somebody was trying to force open the pantry window. He could hear the soft grating of a file against the catch. Whoever it was must have been busy for some time; for, as Jimmy waited, listening, the file completed its work, and the window was raised noiselessly inch by inch. Jimmy could see nothing distinctly, till a gleam of light cut through the darkness, as the unseen visitor opened his lantern.

The sight of the light brought Jimmy to himself.

What followed seemed funny to him when he recalled it later; but at the moment the humorous side of the thing did not appeal to him. His heart was beating wildly, as he groped out for something to throw. His fingers closed on a loaf of bread. He could just see the dim outline of a man’s figure against the open window; and, aiming at a venture, he flung his loaf of bread with all the force at his disposal. There was a dull bump, followed by a yell and a clatter, as the lantern fell to the ground. He had evidently made a good shot.

The burglar, on receipt of the bread, had not waited for more. It was plain that he looked on houses where quartern loaves flew at him from nowhere as unsuitable for his purposes. Jimmy heard his footsteps retreating across the lawn. He went to the pantry window, and looked out. There was too much mist for him to see anything distinctly. But he was certain the man was gone.

He wondered what he had better do. If he gave the alarm, it would only lead to a great deal of confusion, and spoil the rest of a number of people who disliked having their sleep disturbed. It would do no good. The man was not likely to return, knowing that he had once been seen. So Jimmy, having closed the shutters—which should have been done before by Perks—lit another match, collected a plateful of biscuits and some apples, and went back to bed, where, at about half-past four, he managed to get some sleep.

The train which was to take him back to Marleigh started at eleven o’clock. George, the groom, took him down in the dogcart, and Perks gave him a farewell benediction and a lunch-basket on the front steps.

Jimmy always rather liked the journey back to school. Perks seldom failed to come out strong with the food; and on the present occasion everything was in the best taste, notably a couple of bottles of home-brewed ginger beer, of a strength which beat anything he had come across previously.

Whether it was the lack of rest he had had during the night or the potency of the ginger beer, he did not know; but after half an hour an overwhelming feeling of drowsiness came over Jimmy. He could not keep his eyes open.

The next thing he was aware of was a dream-like sensation of seeing the well-known face of Tommy Armstrong at the open window.

It was so absolutely impossible that Tommy should be there that Jimmy could not realise that he was awake. To start with, Tommy was at Marleigh. And, even if he had not been, how could he possibly be outside the carriage?

At this moment the dream-figure spoke.

“Hullo, Jimmy,” it said. “Lend a hand, will you, and lug me in.”

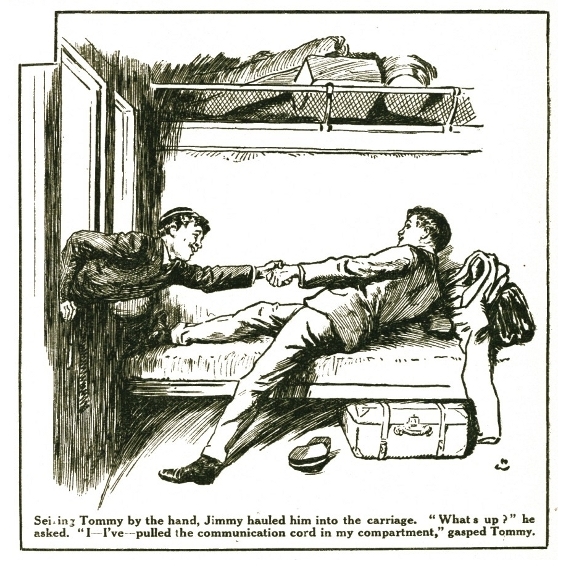

Jimmy shook off the last remnants of sleep and jumped up. Seizing Tommy by the hand, he hauled him into the carriage. As he did so, he was aware that the train was slowing down. It stopped just as Tommy, having rolled off the seat on to the floor, sat up and began to dust himself.

Tommy Armstrong was a freckled, red-haired youth with one of the widest grins ever seen on human face. He was about the same age as Jimmy. They shared a room at Marleigh. Tommy had the reputation of being the most reckless boy who had ever been to Marleigh School. He had absolutely no respect of persons, and why it was that the authorities had not dropped heavily on him before now nobody could understand. Probably it was because, in addition to his recklessness, he possessed also, and could, when he pleased, exhibit, a wonderful charm of manner. The German master, Herr Steingruber, whose life must have been a burden to him through Tommy, was never proof against it. He would set him colossal impositions during school hours, but, as often as he did so, he would cancel them as the result of a few minutes’ conversation with the erring one after school was over. Tommy had a way of asking Herr Steingruber to play the ’cello, to which instrument the German master was devotedly attached, which was always good for a reprieve, whatever the offence may have been.

“What on earth’s up?” asked Jimmy, as the train, with a jarring of brakes, came to a standstill. “What the dickens were you doing outside there?”

“I wasn’t outside there,” replied Tommy calmly. “Get that idea right out of your head. Whatever else you may forget, remember that I have been in here with you the whole time. See? Don’t forget, a financial ruin stares me in the eyeball. I shall have to sell my yacht and aeroplane.”

“What are we stopping for, I wonder!”

“Me. Don’t give it away. They’ll probably be round here in a jiffy.”

“Who?”

“The guard and his crew.”

“But why? What’s happened?”

“I pulled the communication-cord.”

“What! What on earth for?”

Tommy sighed.

“I’m blowed,” he said, “if I can tell you. It was like this. I was alone in the carriage, and that rotten advertisement of theirs about pulling the communication-cord kept catching my eye. I have always wondered what would happen if you did pull it, and after a bit I simply couldn’t stand it any longer, so I just got up and gave the thing a tug. Well, then it struck me that I hadn’t got five pounds to pass over to them when they came round, so I just nipped out of the window and shuffled along, trying to find an empty carriage. Hullo, here they are! I say, guard, what on earth are we stopping for?”

“Someone’s bin and pulled the communication-cord.”

“What’s up? A murder?”

“Someone’s bin ’avin’ a lark with the company, that’s what’s happened. It’s a lark wot’ll cost them five pounds, if I found ’oo it was did it.”

“Well, what’s the matter with asking the people in the carriage where the cord is?”

“There ain’t nobody there.”

“Are we going to stop here all night while you’re hunting for the ghost?”

“I don’t want none of your lip. I shouldn’t be ’arf surprised if it wasn’t you wot did it.”

“Don’t be silly, my good man. Pull yourself together. How could I do it from here? Do you think I’ve got an indiarubber arm?”

“I don’t know about that. You’ve got cheek enough for ’arf a dozen.”

“Go away,” said Tommy coldly. “I don’t like your face. I never did.”

By this time passengers’ heads, protruding from windows, were demanding angrily the cause of the delay. The guard, grumbling, returned to his carriage, and soon afterwards the train started again.

“What on earth are you doing here?” asked Jimmy. “Why aren’t you at school?”

“Got a day off to go and see an uncle of mine, who lives down the line. Good old sort. Gave me a quid. It’ll come in useful this term for paying off tick and other things. Well, what’s been the matter with you? What have you been slacking at home for all this while?”

“Mumps.”

“You look all right now.”

“I am. What’s been happening at Marleigh?”

“Nothing much. Old Steingruber’s been in pretty good form. He’s taken up golf. He’s a bit rottener at it than he is at anything else, which is saying a good deal. You remember him at cricket last term. Well, his golf’s worse than that. He plays with Spinder. Oh, you don’t know Spinder. He’s a new master, and the most awful blighter you ever struck. Specs, hooked nose, getting bald on the top. Frightfully strict. Gives you beans if you do a thing. My life’s been a perfect curse since he arrived. I’m dashed if I know what to do about it. I’ve only just worked off five hundred lines he gave me simply for letting a rabbit loose in form. It was one of Simpson’s rabbits. He’s got a couple. We take ’em up to the dormitory at night, and race them in the corridor. Awful sport. They’re called Blib and Blob. Blib was the one I let loose in the form-room. Spinder collared it, only he gave it to the boot-boy, and I got it back for one-and-six. What have you got in that basket? Great Scott! Cake! Why didn’t you tell me?”

Tommy suspended conversation for the moment, while he finished Jimmy’s lunch.

Jimmy was thinking. Sam Burrows had told him not to let anyone know about the blue stone; but surely, he thought, he need not include Tommy. He was beginning to find the possession of the secret something of a strain. It would be a relief to confide in Tommy.

“I say,” he said.

“Hullo!” said Tommy, his mouth full of cake. “I say, where do you get this cake? It’s the best I ever bit. Keep me well supplied with it. You ought to study my tastes more. If only I had plenty of this sort of stuff I should be happy and contented all the time, instead of gloomy and a nuisance to everyone.”

“I say, Tommy, look at this.”

He fished the stone up from his pocket. Tommy examined it without much enthusiasm.

“I don’t think much of it. What is it?”

“A precious stone of some sort, I think.”

“Let’s have it for a second.” Tommy took possession of the stone, and tried to write his initials on the carriage window.

“It’s a fraud,” he said, with conviction. “If it was a precious stone, it would scratch glass. You’ve been had, my lad. Where did you get the rotten thing? How much did you give for it? It looks like a bit of sealing-wax.”

“I didn’t give anything for it. It was given me to keep by a chap. He had come all the way from India to hand it over to my father, who’s away. So he gave it to me instead, and I’m to let father have it directly he comes back. And, I say, Tommy, swear you won’t say anything about it to a soul.”

“Why should I? And why not, if it comes to that?”

“Because it’ll be frightfully dangerous for me if anybody gets to know I’ve got it. There’s a gang of chaps after it, and they’ll stick at nothing.”

“Pile it on.”

“I’m not rotting. It’s a fact. I’m blowed if I know what there is about the stone that should make it so valuable—as you say, it looks pretty rotten, but I know it is valuable. The chap who gave it me was shot by the other chaps I was telling you about.”

“Shot! What, killed?”

“No. Shot through the shoulder. We were talking in our drive at the time. He told me that he’d been shot at heaps of times since he first got the stone. He’s a chap called Burrows, a soldier. He’d served under my pater in India.”

Tommy looked searchingly at him.

“Look here, Jimmy, are you trying to pull my leg? Because if you are, I’ll roll you under the seat and chuck you out of the window.”

“I swear I’m not. It’s all absolutely true.”

“Well, it’s jolly rum. I don’t see anything in the stone which would make anybody want it. Unless he was a lunatic. Perhaps that’s it. Perhaps a lot of loonies from an asylum are after it. Anyhow, you can have it back. I’ve no use for it.”

Jimmy replaced the stone in his pocket. He had hardly done so when the train slowed down and halted at a small station. The door of the carriage opened, and a man in a brown suit got in, and settled himself in the corner opposite to Jimmy.

But for the fact that the man had a black eye, or rather a bruised eye, Jimmy might not have given him a second look. But a black eye is always picturesque, and demands a closer inspection. So Jimmy looked at him again, and a curious feeling of having seen him before somewhere came upon him.

Their eyes met, and then Jimmy’s heart gave a leap. He had remembered. The face was the same face which had gazed at him through the window when he had seen the blue stone for the first time.

What did it mean? Could the man know? If not, why should he be shadowing him? Perhaps it was all a mistake. This might not be the same man. And yet Jimmy was convinced that it was. He had worn a beard then, and now he was clean-shaven. But the eyes were the same.

As these thoughts raced through Jimmy’s mind, Tommy Armstrong broke the silence.

“I say, Jimmy,” he said, “let’s have another look at that stone.”

Jimmy saw the man in the corner give a slight start, and for a moment he felt physically sick.

“What are you talking about?” he faltered.

But Tommy, all unconscious, went on.

“Don’t be an ass,” he said. “You know what I mean. That rummy blue stone, that what’s-his-name—Burrows gave you. I want to have another look at it.”

(Next week there will be another splendid instalment of this serial.)

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums