The Circle, November 1908

Chapter VII

The Entente Cordiale Is Sealed

IT

HAS been well observed that there are Moments and

Moments. The present, as far as I was concerned, belonged to the more painful

variety.

IT

HAS been well observed that there are Moments and

Moments. The present, as far as I was concerned, belonged to the more painful

variety.

Even to my exhausted mind it was plain that there was need here for explanations. An Irishman’s croquet-lawn is his castle, and strangers cannot plunge on to it unannounced through hedges without being prepared to give reasons.

Unfortunately, speech was beyond me. I could have done many things at that moment. I could have emptied a water-butt, lain down and gone to sleep, or melted ice with a touch of the finger. But I could not speak. The conversation was opened by the other man, in whose soothing hand the hen now lay apparently resigned to its fate. He saw my condition.

“Come right in,” he said, pleasantly. “Don’t knock. Your bird, I think?Part of the classic courtesy of shooting game birds, a stock phrase from one hunter to another to avoid two blasts of shot at a single rising bird.”

I stood there, panting. I must have presented a quaint appearance. My hair was full of twigs and other foreign substances. My face was moist and grimy. My mouth hung open. I wanted to sit down. My legs felt as if they had ceased to belong to me.

“I must apologize”——I began, and ended the sentence with gasps.

The elderly gentleman looked at me with what seemed to me indignant surprise. His daughter looked through me. The man regarded me with a friendly smile, as if I were some old crony dropped in unexpectedly.

“I’m afraid”——I said, and stopped again.

“Hard work big-game hunting in this weather,” said the man. “Take a long breath.”

I took several, and felt better.

“I must apologize for this intrusion,” I said, successfully. “Unwarrantable” would have rounded off the sentence nicely, but instinct told me not to risk it. It would have been mere bravado to have attempted unnecessary words of five syllables at that juncture. I paused.

“Say on,” said the man with the hen, encouragingly. “I’m a human being just like yourself.”

“The fact is,” I said, “I didn’t—didn’t know there was a private garden beyond the hedge. If you will give me my hen”——

“It’s hard to say good-by,” said the man, stroking the bird’s head with the first finger of his disengaged hand. “She and I are just beginning to know and appreciate each other. However, if it must be”——

He extended the hand which held the bird, and at this point a hitch occurred. He did his part of the business, the letting go. It was in my department, the taking hold, that the thing was bungled. The hen slipped from my grasp like an eel, stood for a moment overcome by the surprise of being at liberty once more; then fled and entrenched itself in some bushes at the further end of the lawn.

There are times when the most resolute man feels that he can battle no longer with Fate; when everything seems against him, and the only course left is a dignified retreat. But there is one thing essential to a dignified retreat. One must know the way out. I could hardly ask to be conducted off the premises like the Honored Guest. Nor would it do to retire by the way I had come. If I could have leaped the hedge with a single bound, that would have made a sufficiently dashing and debonair exit. But the hedge was high, and I was incapable at the moment of achieving a debonair leap over a footstool.

The man saved the situation. He seemed to possess that magnetic power over his fellows which marks the born leader. Under his command we became an organized army. The common object, the pursuit of the hen, made us friends. In the first minute of the proceedings the Irishman was addressing me as “me dear boy,” and the other man, who had introduced himself rapidly as Tom Chase, lieutenant in His Majesty’s Navy, was shouting directions to me by name. I have never assisted at any ceremony at which formality was so completely dispensed with. The ice was not merely broken; it was shivered into a million fragments.

“Go in and drive her out, Garnet,” shouted Mr. Chase. “In my direction if you can. Look out on the left, Phyllis.”

Even in that disturbing moment I could not help noticing his use of the Christian name. It seemed to me sinister. I did not like the idea of a dashing young lieutenant in the Royal Navy calling a girl Phyllis whose eyes had haunted me for just over a week; since, in fact, I had first seen them.

Nevertheless, I crawled into the bushes and dislodged the hen. She emerged at the spot where Mr. Chase was waiting with his coat off and was promptly enveloped in that garment and captured.

“The essence of strategy,” observed Mr. Chase, approvingly, “is surprise.”

I thanked him. He deprecated the thanks. He had, he said, only done his duty, as a man is bound to do. He then introduced me to the elderly Irishman, who was, it seemed, a professor—of what I do not know—at Dublin University. By name, Derrick. He informed me that he always spent the summer at Lyme Regis.

“I was surprised to see you at Lyme Regis,” I said. “When you got out at Yeovil I thought I had seen the last of you.”

I think I am gifted beyond other men as regards the unfortunate turning of sentences.

“I meant,” I added speedily, “I was afraid I had.”

“Ah, of course,” he said, “you were in our carriage coming down. I was confident I had seen you before. I never forget a face.”

“It would be a kindness,” said Mr. Chase, “if you would forget Garnet’s as now exhibited. You’ll excuse the personality, but you seem to have collected a good deal of the professor’s property coming through that hedge.”

“I was wondering”——I said with gratitude. “A wash—if I might?”

“Of course, me boy, of course,” said the professor. “Tom, take Mr. Garnet off to your room, and then we’ll have some lunch. You’ll stay to lunch, Mr. Garnet?”

I thanked him for his kindness, and went off with my friend the lieutenant to the house.

“So you’ve met the professor before?” he said, hospitably laying out a change of raiment for me—we were fortunately much of a height and build.

“I have never spoken to him,” I said. “We traveled down together in a very full carriage.”

“He’s a dear old boy, if you rub him the right way.”

“Yes?” I said.

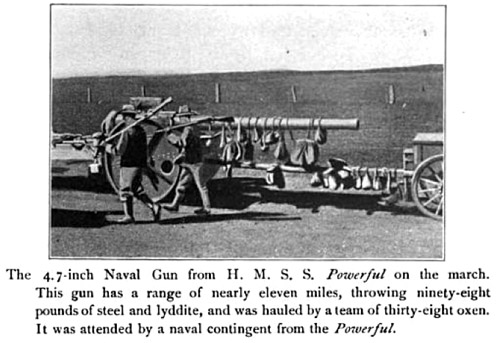

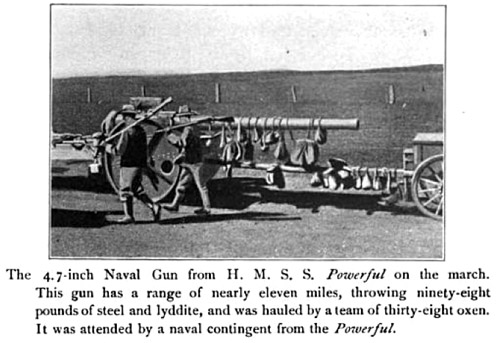

“But—I’m telling you this

for your good and guidance—he can cut up rough. And when he does he goes off

like a four point sevena naval gun with a bore of 4.7 inches, famous for improvised adaptation to field use in the Boer War, as shown here:

.”

.”

We got to know one another very well at lunch.

“Do you hunt hens,” asked Mr. Chase, who was mixing the salad—he was one of those men who seem to do everything a shade better than any one else, “for amusement or by your doctor’s orders?”

“Neither,” I said, “and particularly not for amusement. The fact is, I have been lured down here by a friend of mine who has started a chicken farm”——

I was interrupted. All three of them burst into laughter. Mr. Chase in his emotion allowed the vinegar to trickle on to the cloth, missing the salad-bowl by a clear two inches.

“You don’t mean to tell us,” he said, “that you really come from the one and only chicken farm?”

I could not deny it.

“Why, you’re the man we’ve all been praying to meet for days past. Haven’t we, professor?”

“You’re right, Tom,” chuckled Mr. Derrick.

“Look here, Garnet,” said Mr. Chase, “I hope you won’t consider these questions impertinent, but you’ve no notion of the thrilling interest we all take—at a distance—in your farm. We have been talking of nothing else for a week. I have dreamed of it three nights running. Is Mr. Ukridge doing this as a commercial speculation, or is he an eccentric millionaire?”

“He’s not a millionaire. I believe he intends to be, though, before long with the assistance of the fowls. But I hope you won’t look on me as in any way responsible for the arrangements at the farm. I am merely a laborer. The brain-work of the business lies in Ukridge’s department.”

“Tell me, Mr. Garnet,” said Phyllis, “do you use an incubator?”

“Oh yes, we have an incubator.”

“I suppose you find it very useful?”

“I’m afraid we use it chiefly for the purpose of drying our boots when they get wet,” I said.

Only that morning Ukridge’s spare pair of tennis-shoes had permanently spoiled the future of half-a-dozen eggs which were being hatched on the spot where the shoes happened to be placed. Ukridge had been quite annoyed.

“I came down here principally,” I said, “in search of golf. I was told there were links, but up to the present my professional duties have entirely monopolized me.”

“Golf,” said Professor Derrick, “why, yes. We must have a round or two together. I am very fond of golf. I generally spend the summer down here improving my game.”

I said I should be delighted.

There was croquet after lunch—a game at which I am a poor performer. Miss Derrick and I played the professor and Chase. Chase was a little better than myself; the professor, by dint of extreme earnestness and care, managed to play a fair game, and Phyllis was an expert.

“I was reading a book,” said she, as we stood together watching the professor shaping at his ball at the other end of the lawn, “by an author of the same surname as you, Mr. Garnet. Is he a relation of yours?Magazine had a period here; 1909 book had question mark.”

“I am afraid I am the person, Miss Derrick,” I said.

“You wrote the book?”

“A man must live,” I said, apologetically.

“Then you must have—oh, nothing.”

“I could not help it, I’m afraid. But your criticism was very kind.”

“Did you know what I was going to say?”

“I guessed.”

“It was lucky I liked it,” she said, with a smile.

“Lucky for me,” I said.

“Why?”

“It will encourage me to write another book. I hope it will not trouble your conscience.”

At the other end of the lawn the professor was still patting the balls about, Chase the while advising him to allow for windage and elevation and other mysterious things.

“I should not have thought,” she said, “that an author cared a bit for the opinion of an amateur.”

“It all depends.”

It was my turn to play at this point. I missed—as usual. Miss Derrick turned to me and said:

“I didn’t like your heroine at all, Mr. Garnet.”

“That was the one crumpled roseleafJust as we now cite the fable of the Princess and the Pea as an example of exquisite sensitivity, classical writers cited the Sybarite who was pained by a crumpled roseleaf beneath his couch. W. S. Gilbert gives the line “Some crumpled roseleaf light is always in the way!” to Captain Fitzbattleaxe in Utopia, Limited.. I have been wondering why ever since. I tried to make her nice. Three of the critics liked her.”

“Really?”

“And the modern reviewer is an intelligent young man. What is a ‘creature,’ Miss Derrick?”

“Pamela in your book is a creature,” she replied, unsatisfactorily, with the slightest tilt of the chin.

“My next heroine shall be a triumph,” I said.

She should be a portrait, I resolved, from life.

Shortly after, the game came, somehow, to an end. I do not understand the intricacies of croquet. But Phyllis did something brilliant and remarkable with the balls, and we adjourned for tea, which had been made ready at the edge of the lawn while we played.

The sun was setting as I left to return to the farm, with the hen stored neatly in a basket in my hand. The air was deliciously cool, and full of that strange quiet which follows soothingly on the skirts of a broiling midsummer afternoon. Alone in a sky of the palest blue there twinkled a small, bright star.

I addressed this star.

“She was certainly very nice to me,” I said. “Very nice indeed.”

The star said nothing.

“On the other hand,” I went on, “I don’t like that naval man. He is a good chap, but he overdoes it.”

The star winked sympathetically.

“He calls her Phyllis,” I said.

“Charawk,” said the hen, satirically, from her basket.

Chapter VIII

A Little Dinner at Ukridge’s

“Edwin comes to-day,” said Mrs. Ukridge, quietly.

“And the Derricks,” said Ukridge, sawing at the bread in his energetic way. “Don’t forget the Derricks, Millie.”

“No, dear. Mrs. Beale is going to give us a very nice dinner. We talked it over yesterday.”

“Who is Edwin?” I asked.

We were finishing breakfast on the second morning after my visit to the Derricks’. I had related my adventures to the staff of the farm on my return, laying stress on their interest in our doings, and the Hired Retainer had been sent off next morning with a note from Mrs. Ukridge inviting them to look over the farm and stay to dinner.

“Edwin?” said Ukridge. “Beast of a cat.”

“Oh, Stanley!” said Mrs. Ukridge, plaintively. “He’s not. He’s such a dear, Mr. Garnet. A beautiful, pure-bred Persian. He has taken prizes.”

“He’s always taking something. Generally food. That’s why he didn’t come down with us.”

“A great, horrid beast of a dog bit him, Mr. Garnet.” Mrs. Ukridge’s eyes became round and shone. “And poor Edwin had to go to a cats’ hospital. I’m so afraid that he will be frightened of Bob. He will be very timid, and Bob’s so boisterous.”

“That’s all right,” said Ukridge; “Bob won’t hurt him, unless he tries to steal his bone. In that case we will have Edwin made into a rug.”

“Stanley doesn’t like Edwin,” said Mrs. Ukridge, plaintively.

Edwin arrived early in the afternoon and was shut into the kitchen. He struck me as a handsome cat, but nervous. He had an excited eye.

The Derricks followed two hours later. Mr. Chase was not of the party.

“Tom had to go to London,” explained the professor, “or he would have been delighted to come.”

“He must come some other time,” said Ukridge. “We invite inspection. Look here,” he broke off, suddenly—we were nearing the fowl-run now, Mrs. Ukridge walking in front with Phyllis Derrick—“were you ever at Bristol?”

“Never, sir,” said the professor.

“Because I knew just such another fat little bufferslang, either an elderly man or a foolish, incompetent one there a few years ago. Gay old bird, he was. He”——

“This is the fowl-run, professor,” I broke in, with a moist, tingling feeling across my forehead and up my spine. I saw the professor stiffen as he walked, while his face deepened in color. Ukridge’s breezy way of expressing himself is apt to electrify the stranger.

“You will notice the able way—ha, ha—in which the wire netting is arranged,” I continued, feverishly. “Took some doing, that. By Jove, yes. It was hot work. Nice lot of fowls, aren’t they. We are getting quite a number of eggs now. Hens wouldn’t lay at first. Couldn’t make them.”

I babbled on till from the corner of my eye I saw the flush fade from the professor’s face and his back gradually relax its pokerlike attitude. The situation was saved for the moment, but there was no knowing what further excesses Ukridge might indulge in. I managed to draw him aside as we went through the fowl-run, and expostulated.

“For goodness’ sake be careful,” I whispered. “You’ve no notion how touchy the professor is.”

‘“But I said nothing,” he replied, amazed.

“Hang it, you know, nobody likes to be called a fat little buffer to his face.”

“What else could I call him? Nobody minds a little thing like that. We can’t be stilted and formal. It’s ever so much more friendly to relax and be chummy.”

Here we rejoined the others, and I was left with a leaden foreboding of gruesome things in store. I knew what manner of man Ukridge was when he relaxed and became chummy. Friendships of years’ standing had failed to survive the test.

For the time being, however, all went well. In his rôle of lecturer he offended no one, and Phyllis and her father behaved admirably. They received the strangest theories without so much as a twitch of the mouth.

It was while matters were progressing with such beautiful smoothness that I observed the square form of the Hired Retainer approaching us. Somehow—I cannot say why—I had a feeling that he came with bad news. Perhaps it was his air of quiet satisfaction which struck me as ominous.

“Beg pardon, Mr. Ukridge, sir. That there cat, sir, what came to-day”——

“Oh, Beale,” cried Mrs. Ukridge, in agitation, “what has happened?”

“We was talking in the kitchen, ma’am, when Bob, which had followed me unknown, trotted in. When the cat ketched sight of ’im sniffing about, there was such a spitting and swearing as you never ’eared; and blowed,” said Mr. Beale, amusedly, as if the recollection tickled him, “blowed if the old cat didn’t give one jump, and move in quick time up the chimley, where ’e now remains, paying no ’eed to the missus’ attempts to get him down again.”

“But he’ll be cooked,” cried Phyllis, open eyed.

Ukridge uttered a roar of dismay.

“No, he won’t. Nor will our dinner. Mrs. Beale always lets the kitchen fire out during the afternoon. It’s a cold dinner we’ll get to-night, if that—cat doesn’t come down.”

The professor’s face fell. I had remarked on the occasion when I had lunched with him his evident fondness for the pleasures of the table.

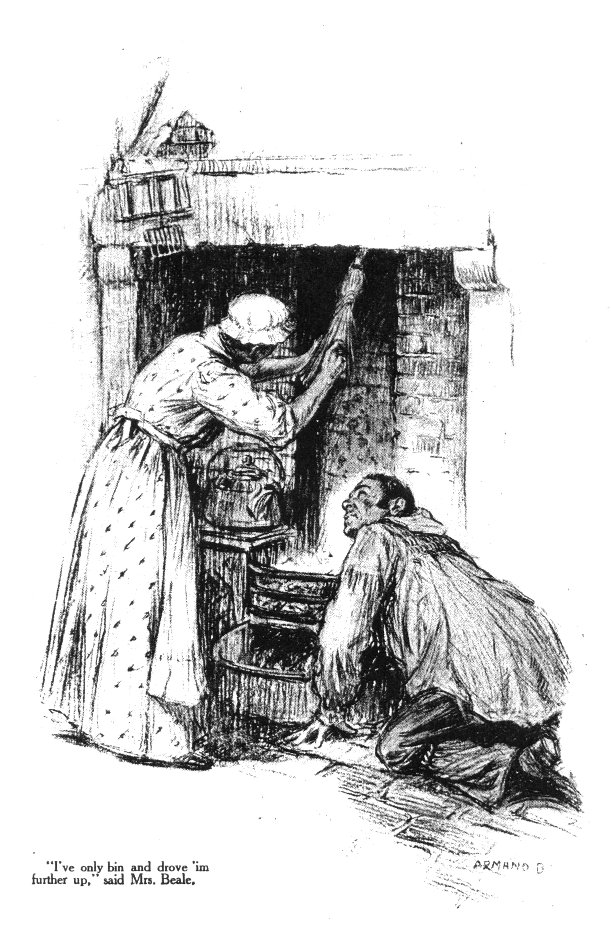

We went to the kitchen in a body. Mrs. Beale was standing in front of the empty grate making seductive cat-noises up the chimney.

“Prod at him with a broom handle, Mrs. Beale,” urged Ukridge.

“I ’ave tried that, sir, but I’ve only bin and drove ’im

further up. What must be,” added Mrs. Beale, philosophically, “must be. He may

come down of his own accord in the night, bein’ ’ungry.”

“I ’ave tried that, sir, but I’ve only bin and drove ’im

further up. What must be,” added Mrs. Beale, philosophically, “must be. He may

come down of his own accord in the night, bein’ ’ungry.”

“Then what we must do,” said Ukridge, in a jovial manner which to me at least seemed out of place, “is to have a regular, jolly picnic-dinner, what? Whack up whatever we have in the larder, and eat that.”

“A regular, jolly picnic-dinner,” repeated the professor, gloomily. I could read what was passing in his mind.

“That will be delightful,” said Phyllis.

“Er, I think, my dear sir,” said her father, “it would be hardly fair of us to give any further trouble to Mrs. Ukridge and yourself. If you will allow me, therefore, I will”——

Ukridge became gushingly hospitable. He would be able to whack up something, he said. There was quite a good deal of the ham left, he was sure. He appealed to me to endorse his view that there was a tin of sardines and part of a cold fowl and plenty of bread and cheese.

“And after all,” he said, speaking for the whole company in the generous, comprehensive way enthusiasts have, “what more do we want in weather like this? A nice, light, cold dinner is ever so much better for us than a lot of hot things.”

The professor said nothing. He looked wan and unhappy.

The sight of the table, when at length we filed into the dining-room, sent a chill through me. It was a meal for the very young or the very hungry. The uncompromising coldness and solidity of the viands was enough to appal a man conscious that his digestion needed humoring. A huge cheese faced us in almost a swashbuckling way. Sardines, looking more oily and uninviting than anything I had ever seen, appeared in their native tin beyond the loaf of bread. There was a ham, in its third quarter, and a chicken which had suffered heavily during a previous visit to the table.

We got through the meal somehow, and did our best to delude ourselves into the idea that it was all great fun; but it was a shallow pretense. The professor was very silent by the time we had finished. Ukridge had been terrible. When the professor began a story—his stories would have been the better for a little more briskness and condensation—Ukridge interrupted him, before he had got half way through, without a word of apology, and began some anecdote of his own. He disagreed with nearly every opinion he expressed. It is true that he did it all in such a perfectly friendly way, and was obviously so innocent of any intention of giving offense, that another man might have overlooked the matter. But the professor, robbed of his good dinner, was at the stage when he had to attack somebody. Every moment I had been expecting the storm to burst.

It burst after dinner.

We were strolling in the garden, when some demon urged Ukridge, apropos of the professor’s mention of Dublin, to start upon the Irish question. He had boomed forth some very positive opinions of his own on the subject of Ireland before I observed the ire in the professor’s eye. When I did, I suppose I must have whispered louder than I had intended, for the professor heard my words, and they acted as the match to the powder.

“He’s touchy on the Irish question, is he?” he thundered. “Drop it, is it? And why? Why, sir? I’m one of the best-tempered men that ever came from Ireland, let me tell you, and I will not stay here to be insulted by the insinuation that I cannot discuss Irish affairs as calmly as any one.”

“But, professor”——

“Take your hand off me arm, Mr. Garnet. I will not be treated like a child. I am as competent to discuss the affairs of Ireland without heat as any man, let me tell you.”

“Father”——

“And let me tell you, Mr. Ukridge, that I consider your opinions poisonous. Poisonous, sir. And you know nothing whatever about the subject, sir. I don’t wish to see you or to speak to you again. Understand that, sir? Our acquaintance began to-day, and it will cease to-day. Good-night to you. Come, Phyllis, my dear. Mrs. Ukridge, good-night.”

Mr. Chase, when he spoke of four point seven guns, had known what he was talking about.

Chapter IX

Dies IraeLatin for “day of wrath”; a chant from the Requiem Mass [IM]

It was Ukridge who was to blame for the professor’s regrettable explosion and departure, and he ought by all laws of justice to have suffered for it. As it was, I was the only person materially affected. It did not matter to Ukridge. He did not care twopence one way or the other.

But to me it was a serious matter. More than serious. If I have done my work as historian with an adequate degree of skill, the reader should have gathered by this time the state of my feelings.

It is true that we had not seen a great deal of one another, and that, when we had met, our interviews had been brief and our conversation conventional; but it is the intervals between the meetings that do the real damage. Absence, as the poet neatly remarks, makes the heart grow fonder.The idea dates back to Roman writings, but the English poet cited is Thomas Haynes Bayly (1797–1831), from the ballad “Isle of Beauty” And now, thanks to Ukridge’s amazing idiocy, a barrier had been thrust between us. It was terrible to have to reestablish myself in the good graces of the professor before I could so much as begin to dream of Phyllis.

Ukridge gave me no balm.

“Well, after all,” he said, when I pointed out to him quietly but plainly my opinion of his tactlessness, “what does it matter? There are other people in the world besides the old buffer. And we haven’t time to waste making friends, as a matter of fact. The farm ought to keep us busy. I’ve noticed, Garny, old boy, that you haven’t seemed such a whale for work lately as you might be. You must buckle to, old horse. We are at a critical stage. On our work now depends the success of the speculation. Look at those cocks. They’re always fighting. Fling a stone at them. What’s the matter with you? Can’t get the novel off your chest, what? You take my tip, and give your mind a rest. Nothing like manual labor for clearing the brain. All the doctors say so. Those coops ought to be painted to-day or to-morrow. Mind you, I think old Derrick would be all right if one persevered”——

“And didn’t call him a fat old buffer, and contradict everything he said, and spoil all his stories by breaking in with chestnuts of your own in the middle,” I interrupted, with bitterness.

“Oh, rot, old boy, he didn’t mind being called a fat old buffer. You keep harping on that. What was the matter with old Derrick was a touch of liver. You should have stopped him taking that cheese. I say, old man, just fling another stone at those cocks, will you. They’ll eat one another, as sure as fate.”

I had hoped, fearing the while that there was not much chance of such a thing happening, that the professor might get over his feeling of injury during the night, and be as friendly as ever next day. But when I went down to the beach for a bath the following morning, I found him there and he cut me in the most uncompromising fashion.

Phyllis was with him at the time, and also another girl who was, I supposed from the strong likeness between them, her sister. She had the same soft mass of brown hair. But to me she appeared almost commonplace in comparison.

It is never pleasant to be cut dead. It produces the same sort of feeling as is experienced when one treads on nothing where one imagined a stair to be. In the present instance the pang was mitigated to a certain extent—not largely—by the fact that Phyllis looked at me. She did not move her head, but nevertheless she certainly looked at me. It was something. She seemed to say that duty compelled her to follow her father’s lead and that the act must not be taken as evidence of any personal animus.

That, at least, was how I read off the wireless message.

Two days later I met Mr. Chase in the village.

“Hullo, so you’re back,” I said.

“You’ve discovered my secret,” said he. “Will you have a cigar or a cocoanut?”At fairground try-your-skill booths, this was a traditional choice of prizes

There was a pause.

“Trouble, I hear, while I was away,” he said.

I nodded.

“The man I live with, Ukridge, did it. Touched on the Irish question.”

“Home Rule?”

“He mentioned it among other things.”

“And the professor went off?”

“Like a bomb.”

“He would. It’s a pity.”

I agreed. I am glad to say that I suppressed the desire to ask him to use his influence, if any, with Mr. Derrick to effect a reconciliation. I felt that I must play the game.

“I ought not to be speaking to you, you know,” said Mr. Chase. “You’re under arrest.”

“He’s still”—— I stopped for a word.

“Very much so. I’ll do what I can.”

“It’s very good of you.”

“So long.”

And Mr. Chase walked on with long strides to the cob.

The days passed slowly. I saw nothing more of Phyllis or

her sister. The professor I met once or twice on the links. I had taken

earnestly to golf in this time of stress. Golf, it has been said, is the game

of disappointed lovers. On the other hand, it has further been pointed out that

it does not follow that because a man is a failure as a lover he will be any

good at all on the links. My game was distinctly poor at first. But a round or

two put me back into my proper form, which is fair. The professor’s demeanor

at these accidental meetings on the links was a faithful reproduction of his

attitude on the beach.

The days passed slowly. I saw nothing more of Phyllis or

her sister. The professor I met once or twice on the links. I had taken

earnestly to golf in this time of stress. Golf, it has been said, is the game

of disappointed lovers. On the other hand, it has further been pointed out that

it does not follow that because a man is a failure as a lover he will be any

good at all on the links. My game was distinctly poor at first. But a round or

two put me back into my proper form, which is fair. The professor’s demeanor

at these accidental meetings on the links was a faithful reproduction of his

attitude on the beach.

Once or twice, after dinner, I lit my pipe and walked out across the fields through the cool summer night till I came to the hedge that shut off the Derricks’ grounds—not the hedge through which I had made my first entrance, but another, lower and nearer the house. Standing there under the shade of a tree I could see the lighted windows of the drawing-room.

Generally there was music inside, and, the windows being opened on account of the warmth of the night, I was able to make myself a little more miserable by hearing Phyllis sing. It deepened the feeling of banishment.

I shall never forget those furtive visits. Life seemed a poor institution during these days.

(To be continued)

Editor’s Notes:

Your bird, I think?: Part of the classic courtesy of shooting game birds, a stock phrase from one hunter to another to avoid two blasts of shot at a single rising bird.

a four point seven: a naval gun with a bore of 4.7 inches, famous for improvised adaptation to field use in the Boer War, as shown here:

crumpled roseleaf: Just as we now cite the fable of the Princess and the Pea as an example of exquisite sensitivity, classical writers cited the Sybarite who was pained by a crumpled roseleaf beneath his couch. W. S. Gilbert gives the line “Some crumpled roseleaf light is always in the way!” to Captain Fitzbattleaxe in Utopia, Limited.

buffer: slang, either an elderly man or a foolish, incompetent one

Dies Irae: Latin for ‘day of wrath’; a chant from the Requiem Mass [IM]

Absence, as the poet neatly remarks, makes the heart grow

fonder: The idea dates back to Roman writings, but the English poet cited is Thomas Haynes Bayly (1797–1831), from the ballad “Isle of Beauty”

“Will

you have a cigar or a cocoanut?”: At fairground try-your-skill booths, this was a traditional choice of prizes

Printer’s error corrected above:

Magazine had a period in “Is he a relation of yours.”; 1909 book has question mark.

—Notes by Neil Midkiff, with contributions from Ian Michaud

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums