The Story Thus Far:

ANN MOON, a beautiful New York girl, comes to London for a visit. T. Paterson Frisby, her wealthy uncle, receives the news with groans; after which he hires a chaperon for the young lady—the impecunious Lady Vera Mace, aunt of the even more impecunious Godfrey, Lord Biskerton (“Biscuit”), and sister of the still more impecunious Earl of Hoddesdon, Biscuit’s father—and hopes for the best.

Katherine Valentine, another lovely American, also comes to London—to visit her uncle, Major Flood-Smith. She, it develops, has been sent over by an irate parent to help her forget a suitor regarded by the aforementioned parent as undesirable.

With the arrival of the young ladies, the excitement begins. Aided and abetted by his auntie, Biscuit promptly becomes engaged to the wealthy Miss Moon, and his lordship’s family is delighted. But Biscuit is worried. He must elude his creditors until after the wedding. But how?

Cometh inspiration! Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, dons a huge beard. Is it an effective disguise? Can his enemies recognize him? To answer these vital questions, his lordship (and the beard) goes to the Berkeley, where the fair Ann and his father are lunching together. If Ann fails to spot him—behind the big bush—he is safe!

Now to Godfrey, Lord Biskerton’s dearest friend—“Berry” Conway, T. Paterson Frisby’s secretary, and owner of a derelict copper mine: “The Dream Come True.”

Frisby, knowing that the mine is valuable, advises Berry to sell it to one J. B. Hoke (secretly in his employ) for the princely sum of five hundred pounds; and Berry prepares to do so. . . .

Berry lunches at the Berkeley. There, seated at a near-by table, is a fellow who should be watched—a strange and most sinister Russian!

Biscuit’s father enters—and Ann. Berry’s heart does a flipflop. He likes the lovely American. . . . The bearded villain departs. Ann follows. The bearded villain gets into his car. Ann gets into hers. Berry steps in beside her.

“Follow that ruffian!” our hero whispers. “I’m a member of the Secret Service!” And the charming Ann proceeds to step on the gas!

IV

IN THE car which was following the Biscuit there had at first reigned a silence broken only by the whirring of the engines as Ann’s shapely foot bore down on the accelerator. It was not until the Kingston by-pass had been reached that its two occupants substituted talk for meditation. Each had begun the journey borne down by weight of thought, and each had good reason to think.

Ann was a conscientious girl. Indeed, her conscience, the legacy of a long line of New England ancestors, had always had an unpleasant habit of spoiling for her many of the more attractive happenings of life. It had clawed her in the restaurant. It now bit her. It was a conscience that seemed to possess all the least likable qualities of a wildcat.

She could not deceive herself. Hers was essentially an honest nature, and she was well aware that, having pledged herself to marry Lord Biskerton, she had limited the scope of her actions. There are certain things which an engaged girl has not the right to do. Or, if she does them, she must not like doing them. As, for instance, catching the eye of strange young men in restaurants. As, for further instance, thinking long and earnestly about a strange young man whose eye she has caught in a restaurant and wishing she could get to know him. And, for a final instance, allowing such a young man to leap into her car and initiate what, despite its grim, official, Secret Service nature, Conscience persisted in describing as a joy-ride.

“Don’t talk to me about the call of duty,” said Conscience, in its worst New England manner. “You’re liking it.”

And Ann had to admit that she was. Reluctantly, she was obliged to confess to herself that she had never felt happier since, at the age of fourteen, she had received a signed photograph from John Barrymore.

IF THE possession of parents with a great deal of money and a high social position has a defect, it is that it forces a girl to lead a rather sheltered and conventional life. Ann’s, ever since she was old enough to remember, had been lived in a luxurious and somewhat narrow groove. A finishing school in Paris, a series of seasons in New York, winters at Palm Beach or Aiken, summers in Maine or at Southampton. . . . A cramping existence for a romantic soul.

The men she knew were well-groomed, handsome, polite, but—well, ordinary. Of a pattern. Sometimes she had to collect herself to remember which was which. This one beside her was something new.

Nevertheless, it was quite wrong of her—and she knew that it was quite wrong—to feel this extraordinary fluttering sensation. She should either have refused his extraordinary request, or if an excusable desire to assist the Secret Service of Great Britain had led her to comply with it, should have preserved a detached and impersonal attitude, as if she had been a taxi-driver.

So Ann drove on, and her conscience clawed her abominably.

As for Berry, it would be too much to say that anything in the nature of a real reaction had set in from the mood of rash impulsiveness which had spurred him on to take that sudden leap into this car. He still felt he had done the right thing. Looking back, he could find nothing in his conduct to deplore. Behavior which in other circumstances might possibly have lain open to the charge of being slightly eccentric became on a day like this normal and prudent. Had he not acted as he had done, this wonderful girl would have passed out of his life forever. To prevent a tragedy so unthinkable, no course of action could be called injudicious.

Nevertheless, he was sufficiently restored to sanity to realize that his position might be described as one of some slight embarrassment. Like an enthusiastic but ill-advised sportsman in the jungles of India who has caught a tiger by the tail, he was feeling that he was all right so far but that his next move would require a certain amount of careful thought.

And so, wrapped in silence, the car turned into the Kingston by-pass. The other car was bowling rapidly ahead over the smooth concrete. Where its occupant was going it was impossible to guess, but he was certainly on his way.

Berry was the first to break the silence:

“This is most awfully good of you.”

“Oh, no,” said Ann.

“Oh, yes.”

“Oh, no.”

“Oh, but it is,” said Berry.

“Oh, but it isn’t,” said Ann.

“Well, all I can say,” said Berry, “is that I think it’s most awfully good of you.”

These polite exchanges seemed to diminish the tension. Berry began to breathe again, and Ann went so far as to take an excited eye off the road and flash it at his face. Seen in profile, that face appealed to her strongly. Strenuous exercise and a sober life had given Berry rather a good profile, lean and hard-looking. There were little muscles over his cheekbones and a small white scar in front of the ear which had an attractive and exciting aspect. A bullet graze, Ann knew, would cause a scar just like that.

“Most girls would have been scared stiff,” said Berry.

“Well, I was.”

“Yes,” said Berry, with rising enthusiasm. “But you didn’t hesitate. You didn’t falter. You took the situation in in a second, and were off like a flash.”

“Who is he?” asked Ann breathlessly, peering through the windshield at the flying two-seater. “Or,” she added, “mustn’t you say?”

BERRY would have preferred not to say, but there was plainly nothing else to be done. The owner of a commandeered car has certain rights. He felt that it was fortunate that in his meditations in the restaurant he had gone so deeply into this question of the identity of the bearded bird.

“I think,” he said, “he is The Sniffer.”

“The Sniffer?” Ann’s voice was a squeak. “What Sniffer? How do you mean The Sniffer? Who is The Sniffer? Why The Sniffer?”

“The head of the great cocaine ring. They call him The Sniffer. If, that is to say, he is the man I suppose. He may be a perfectly innocent person . . .”

“Oh, I hope not.”

“. . . who has the misfortune to resemble one of the most dangerous criminals at present in the country. But I feel sure it’s the man himself. You have probably heard how the drug traffic has been increasing of late?”

“No, I haven’t.”

“Well, it has. And it is this man who is responsible.”

“The Sniffer?”

“The Sniffer.”

There was silence for a moment. Then Ann drew a deep breath.

“I suppose all this seems very ordinary to you,” she said. “But I’m just quivering like an aspen. You take it as just a matter of course, I suppose?”

Young men in old England do not possess New England consciences. There is the Nonconformist conscience, but Berry was not subject even to that. He replied not only steadily, but with a quiet smile.

“Well, of course, it is all in the day’s work,” he said.

“You mean this sort of thing is happening to you all the time?”

“More or less.”

“Well!” said Ann.

It was a personal question, she felt, but she could keep it in no longer.

“How did you get that scar?” she asked breathlessly.

“Scar?”

“There’s a little white scar just in front of your ear. Was that caused by a bullet that grazed you?”

Berry swallowed painfully. Girls bring these things on themselves, he felt. Look at Othello and Desdemona. Othello hadn’t dreamed of saying all that stuff about moving accidents by flood and field, of hair-breadth ’scapes i’ the imminent deadly breach, until the girl dragged it out of him with her questions. Othello knew perfectly well that when he talked of the cannibals that each other eat and the men whose heads do grow beneath their shoulders he was piling it on. But what could he do?

And what, in a similar situation, could Berry Conway do?

“It was,” he said, and felt that from now on nothing mattered.

“Goo!” said Ann. “It must have come pretty close.”

“It would have come closer,” said Berry, his better self now definitely dead, “if I had fired a second later.”

“You fired?”

“Well, I had to.”

“Oh, I’m not blaming you,” said Ann.

“I saw his hand go to his pocket . . .”

“Whose hand?”

“Jack Molloy’s. It was when I was rounding up the Molloy gang.”

“Who were they?”

“A gang of men who went in for arson.”

“Firebugs?”

“THAT’S it,” said Berry, wishing he had thought of the word himself. “They had a headquarters in Deptford. The chief sent me there to spy out the ground, but my beard came off . . .”

“Were you wearing a beard?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t think I should like you in a beard,” said Ann, critically.

“I never wear one,” Berry hastened to explain, “unless I’m rounding up a gang.”

“How many gangs have you rounded up?”

“I forget.”

“It must be very interesting work, rounding up gangs.”

“Oh, it is.”

“Look!” said Ann. “The Sniffer’s gone into that inn.”

Berry followed her gaze.

“So he has.”

“What are you going to do?”

This was a point which was perplexing Berry, also. In the exhilaration of this ride, he had rather overlooked the fact that sooner or later it would be necessary to do something.

“Well . . .” he said.

Inspiration came to him, as it had come to Lord Biskerton. The afternoon was of a warmth that turned the thoughts in that direction. He would go in and have a drink.

“Would you mind waiting here?” he said.

“Waiting?”

She saw a stern, cold look come into his face.

“I’m going in after him.”

“Well, can’t I come, too?”

“No. There may be unpleasantness.”

“I like unpleasantness.”

“No,” said Berry firmly. “Please.”

Ann sighed.

“Oh, very well. Have you got your gun?”

“Yes.”

“Well, have it ready,” said Ann, “and don’t fire till you see the whites of his eyes.”

BERRY disappeared. He walked, Ann thought, just like a bloodhound. Leaning back against the warm leather, she gave herself up to delicious meditation. It was the first time anything of this kind had happened to Ann Moon. Never before had she been even in so much as a night-club raid. The only occasion on which she had ever touched lawlessness and crime had been once on the road between New York and Piping Rock, when a motorcycle policeman had handed her a ticket for exceeding the speed limit.

And then suddenly in the midst of her ecstasy something hard and sharp dug into the roots of her soul.

“Hey!” said Conscience unpleasantly, resuming work at the old stand. “Just a moment!”

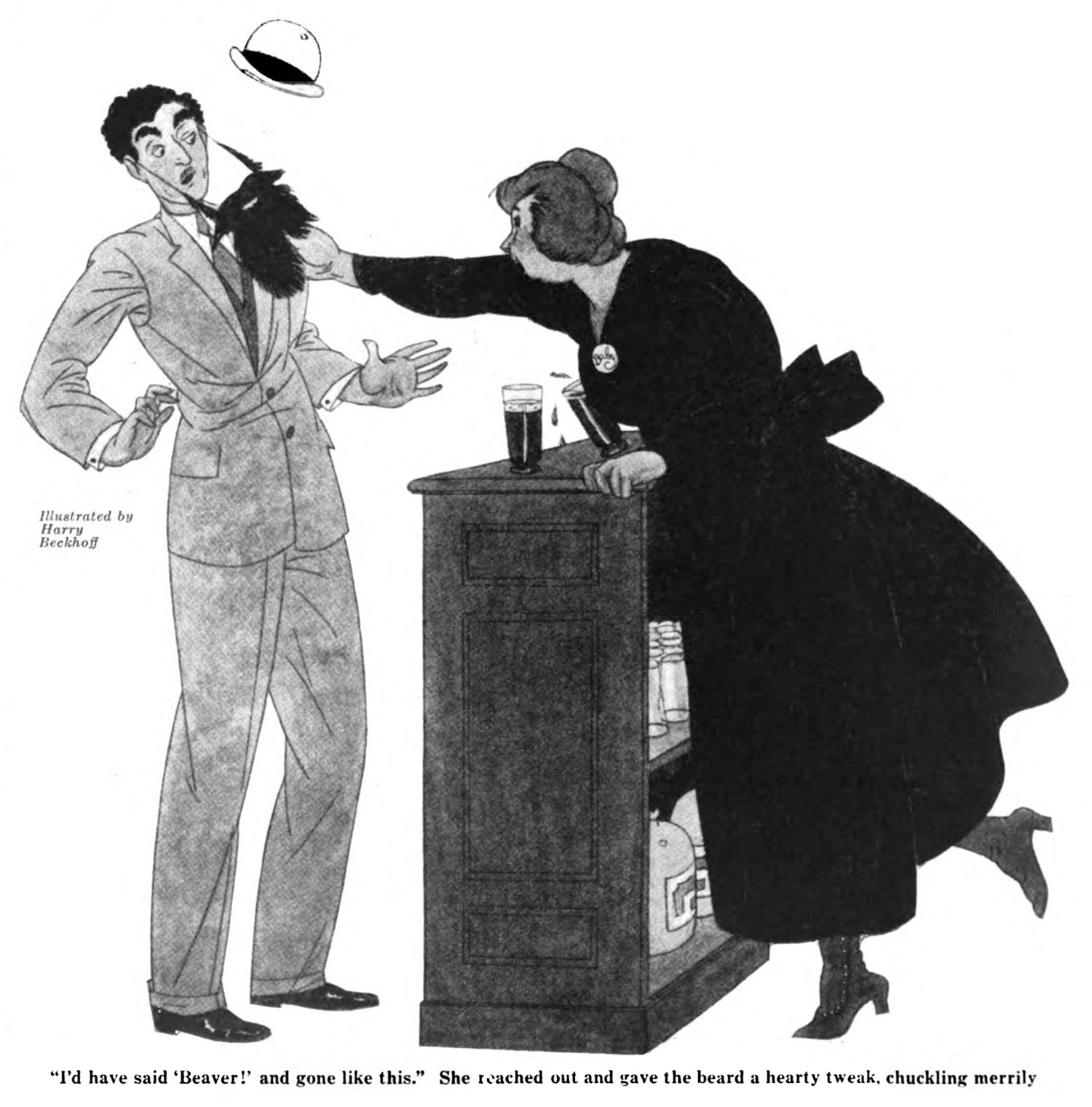

The saloon bar of the Jolly Harvesters at the moment of Lord Biskerton’s entry was unoccupied save by a robust lady in black satin with the sunlight, or something similar, in her hair and a large brooch athwart her bosom with the word “Baby” written across it in silver letters. She stood behind the counter, waiting, like some St. Bernard dog on an Alpine pass, to give aid and comfort to the thirsty. She smiled genially at the Biscuit, and favored him with a summary of the weather.

“Nice day,” she said.

“Of the best,” agreed the Biscuit cordially.

A foaming mug changed hands, and they fell into that pleasant, desultory chat which is customary on these occasions.

The art of exchanging small talk across the counters of saloon bars is not given to everybody. Many of the world’s finest minds have lacked the knack. The late Herbert Spencer is a case in point. But the Biscuit was in his element. He was at his best with barmaids. He had just the right manner and said just the right things. He was, moreover, a good listener. And as every barmaid has a long, complicated tale of grievances against her employer to tell, this gift is almost more valuable than that of easy speech.

By the time he had quaffed a quarter of a pint of Surrey ale, relations of cordial intimacy had been established between his hostess and himself. So much so that the former at last felt justified in giving the conversation a more personal turn. Right from the start she had had a critical eye on the beard, but until now her natural breeding had kept her from anything in the shape of verbal comment.

“Why ever do you wear that beard?” she asked.

“It’s the only one I’ve got,” said the Biscuit.

“It looks funny.”

“Don’t you like it?”

“Oh, I’ve got nothing against it. It looks funny, though.”

“It would look a lot funnier,” argued the Biscuit, “if it was half green and half pink.”

THE barmaid considered this, and was inclined to agree.

“Well, it does look funny,” she said.

“Do you know how I got this beard?” asked the Biscuit.

“Grew it, I suppose.”

“Not at all. Far from it. Very much otherwise. It’s a long story, and reflects a good deal of discredit on some of the parties concerned. When I was a baby, you must know, I was a beautiful little girl. But one day my nurse took me out in my perambulator and stopped to talk to a soldier, as nurses will, and when her back was turned a wicked gypsy sneaked out of the bushes, carrying in her arms an ugly little boy with a beard. And do you know what she did? She stole me out of my perambulator and put that ugly little boy with the beard in my place. And ever since then I’ve been an ugly little boy with a beard.”

“Pity she didn’t leave a razor, too.”

“Razors are no use,” said the Biscuit. “They just fall back blunted and discouraged. So do barbed-wire clippers. One doctor I consulted advised me to set fire to the thing. I pointed out that this might possibly destroy the growth but that I also must inevitably perish in the conflagration. He seemed impressed, and said he had never thought of that. The whole affair is most unpleasant and constitutes a very difficult problem.”

“Well, do you know what I’d have done, if you had come in here a few years ago when everybody was doing it?”

“What?”

“I’d have said ‘Beaver!’ and gone like this.”

She reached out and gave the beard a hearty tweak. As she did so, she chuckled merrily.

It was the last chuckle she was to utter for days and days. Indeed, many people say that she was never quite herself again. Berry, turning the door-handle at that moment, stood transfixed as a piercing scream smote his ears. It sounded like part of a murder. He snatched the door open, and once more stood transfixed. In fact, he was now, if anything, a trifle more transfixed than he had been before.

The spectacle he beheld was enough to transfix anyone. Behind the counter, holding a beard of imperial cut in her hand, stood a barmaid. She seemed upset about something. In front of the counter, also ill at ease, stood his old school friend Lord Biskerton. Berry stared. Many a time had he had nightmares much less weird than this.

The next moment the picture in still life had dissolved. Snatching the beard from the barmaid, the Biscuit replaced it hurriedly on his face. And the barmaid, uttering a long, whistling sigh, fell over sideways in what appeared to be a ladylike swoon.

The Biscuit, though kindly disposed to the barmaid and ranking her among those whose conversation he enjoyed, was not feeling fond enough of her to remain and apply first aid. He wished to be elsewhere, and that right speedily. He turned, bounded towards the door, saw Berry and stopped in midstride.

“Biscuit!” cried Berry.

“Oh, my God!” said Lord Biskerton.

WITH no further comment for the moment, he seized Berry by the arm and hurried him along the passage. Only when they were in the privacy of the stable-yard, concealed from view by a stone wall, did he pause for speech.

“What on earth are you doing here?”

“What are you?”

“I was on my way to Sandown. What brought you here?”

“I followed you to see what you were up to.”

“How do you mean, up to?”

“Well, dash it,” said Berry, “when you go charging about all over London in a long beard. . . .”

The Biscuit was registering deep concern.

“Do you mean to say,” he faltered, shaken, “that you recognized me all along?”

It was not for Berry to dispel this idea. A swift thinker, he saw that he had been given the choice of appearing in the light of a shrewd and lynx-eyed observer and of a gullible chump. He chose the former.

“Of course I recognized you,” he said stoutly.

“Not in Bond Street?” pleaded the Biscuit.

“Certainly.”

“You mean, right from the start, directly I spoke to you?”

“Of course.”

“Well, why didn’t you say so?”

“I was humoring you, you old ass.”

“Humoring me?”

“Yes. I thought you would be disappointed if you didn’t imagine you had fooled me.”

“Gosh!” said the Biscuit, in the depths.

“What was the idea?”

“Berry,” said the Biscuit, his voice shaking, “do you suppose that Ferraro and everybody at the Berkeley knew who I was?”

“I suppose so.”

“Well, all I can say is,” said the Biscuit, “this opens up a new line of thought.”

He followed this line of thought for a while in silence.

“I bought that beard to deceive my creditors,” he explained, at length. “There’s a whole pack of them baying on my trail, and I thought that if I could assume some impenetrable disguise I could go about London undetected. But you say you saw through the thing at once?”

“In a flash.”

“Then what it comes to,” said Lord Biskerton despondently, “is that I shall have to leave the metropolis after all. I daren’t risk being jerked before a tribunal and having my financial condition X-rayed in the county court. I must lie low somewhere. Bexhill, perhaps. Southend, possibly. But, good Lord! How am I to explain?”

“Explain?”

“WELL, dash it, I shall have to give some explanation of why I’ve suddenly disappeared. I’ve just got engaged to be married. My fiancée will be a little surprised, won’t she, if I vanish off the map without a word?”

“I never thought of that,” said Berry.

“I only just thought of it myself,” admitted the Biscuit handsomely. “How would it be to write and tell her I’ve broken my leg and am confined to bed? No. She would come and see me, complete with flowers and grapes. Of course she would. Silly of me. Dash it, this is complex.”

“I know,” said Berry. “Mumps.”

“What?”

“Say you’ve got mumps. She won’t come near you then.”

The Biscuit patted his shoulder with a trembling hand.

“Genius,” he said. “Absolute genius, probably inherited from male grandparent. You’ve solved it, old boy. The only thing to decide now is where shall I go? I must go somewhere. I shall sell a few trinkets to obtain a bit of the ready for necessary expenses, and then fly at dead of night to . . . well, where? It must be somewhere in the wilds. No good a place like Brighton, for instance. Dykes, Dykes and Pinweed probably spend their week-ends in Brighton. Bexhill? I don’t know. Hawes and Dawes have most likely got bungalows there. I believe Wigan would be safest, after all.”

The history of this summer day has shown already that Berry Conway’s brain was at its nimblest. Ever since Mr. Frisby had breezed into the office and given him the freedom of the city, he had been in a highly stimulated cerebral condition. To this must be attributed the inspiration which seized him now.

“Biscuit,” he said, “I’ve got it. The fellow who lives next door to me—Bolitho his name is, not that it matters—has had to leave suddenly for Manchester . . .”

“He been having unpleasantness with his creditors, too?” asked Lord Biskerton sympathetically.

“He wants to let his house, furnished. You could walk right in. I’ll see him this evening, if you like. Or he may have gone already. Anyway, I could fix things through the house agent. That’s the thing for you to do. Nobody would ever find you in Mulberry Grove. You could lie low there for the rest of your life. And we should be next door to each other.”

“Prattle across the fence of an evening?” cried the Biscuit enthusiastically.

“That’s it.”

“Gossip about the neighbors! Borrow each other’s garden roller!”

“Exactly.”

“Berry, old boy,” said Lord Biskerton, “you’ve hit it. That male grandparent of yours must have been a perfect mass of brain cells. I expect they ran excursion trains to see him. Fix up the details, and drop me a line at my flat. Drop it dashed soon, mark you, because it’s only a matter of days before I shall feel the hot breath of Dykes, Dykes and Pinweed on the back of my neck. I’m going to enjoy life in the suburbs. Get a nice rest.”

“I’ll have everything settled tonight.”

“God bless you! A true friend, if ever man had one. And now,” said the Biscuit, “I suppose I had better be getting back to that unfortunate female and explaining that I’m on my way to a fancy dress garden party or something. She had a severe shock, poor child, when the fungus came away in her hands. But no doubt I shall be able to smooth things over. How did you get down here, by the way?”

“In a car,” said Berry guardedly.

“Your own?”

“No.”

“Hired, eh? Well, I think I will remain lurking here till you’ve receded a parasang or two. Common prudence suggests the course. I owe a bit here and there at various garages, and your bloke may quite possibly be attached to one of them. So forgive me if I don’t come to see you off.”

“I will.”

“What’s the name of this desirable residence I’m renting?”

“Peacehaven.”

“Peacehaven!” said the Biscuit. “The very sound of the word is balm. In passing, old boy, the fine old crusted title will have to go, I’m afraid. No mention of the Sieur de Biskerton, if you don’t mind. Tell this bird Bolitho that a Mr. Smith wishes to take his shack, with use of bath. One of the Smithfield Smiths. Right. And now to trickle back and comfort Baby. When I left her, poor lamb, she was snorting like a steam engine and turning blue round the nostrils.”

BERRY came out of the Jolly Harvesters, smiling contentedly. He had his plan of action perfectly shaped. He would tell the girl that the suspect had cleared himself, had proved not to be The Sniffer after all. And then he and she would drive off into fairyland together and talk together of all those things which suit a perfect summer day.

A good program, he felt. Even an admirable program.

But programs are notoriously subject to alteration without warning. Suddenly, abruptly, as if he had received some deadly stroke, the smile faded from his face, and he stared about him with a fallen jaw.

The car had disappeared.

About the entry of Lord Biskerton into the suburb which was to be his temporary home there was nothing that savored even remotely of the ostentatious or the spectacular, no suggestion whatever of a conquering king taking seisin of subject territory. He behaved from the start like one desirous of attracting as little attention to himself as possible. A purist might even have considered him furtive.

Having partaken of an early lunch at his club, he stole out onto the front steps, looked keenly up and down the street with his hat well over his eyes, and then, leaping into a passing taxi, drove to Victoria, where he caught the 1:59. Only when the train rolled out of the station did he allow himself to relax. Unless Dykes, Dykes and Pinweed were hiding under the seat, he was now safe.

VALLEY FIELDS, when he reached it a short while later, came as an agreeable surprise. The very station had the look of a country station. Grass banks sloped away from it, gayly decorated with cabbages, beets, and even roses. Not to mention four distinct beehives. The Biscuit came to the conclusion that Berry did not know a good thing when he saw it. Why, Valley Fields, as far as a cursory inspection would allow him to judge, appeared to be the sort of place an American songwriter would have wanted to go back, back, back to. It was in excellent humor that he called at the offices of Messrs. Matters and Cornelius, House Agents, for the keys of his new domain.

Mr. Cornelius welcomed him paternally. He was an old gentleman of druidical aspect with a long white beard at which the Biscuit, that connoisseur of beards, looked with respectful envy. Full of patriotic spirit where Valley Fields was concerned, Mr. Cornelius approved of those who wished to come and live there.

“A most desirable property,” he assured the Biscuit. “A bijou bower of verdure. The house is a beautifully appointed modern residence, fitted with every up-to-date convenience, and in perfect order.”

“Company’s own water?” asked the Biscuit, keenly.

“Certainly.”

“Both H. and C.?”

“Quite.”

“The usual domestic offices?”

“Of course.”

“And how about the estate?”

“Peacehaven,” said Mr. Cornelius, “has parklike grounds extending to upwards of an eighth of an acre.”

“What happens if you get lost?” asked the Biscuit, interested. “I suppose they send St. Bernard dogs in after you.”

He proceeded on his way, and came presently to his journey’s end, Mulberry Grove. And his contentment deepened. For his eye, as he approached, was caught by what appeared to be a most admirable pub just round the corner. He went in and tested the beer. It was superb. Every explorer knows that the most important thing in a strange country is the locating of the drink-supply: and the Biscuit, satisfied that this problem had been adequately solved, came out of the hostelry with a buoyant step, and a moment later the full beauties of Mulberry Grove were displayed before him.

In the course of a letter to the South London Argus exposing the hellhounds of the local gas light and water company, Major Flood-Smith of Castlewood had once referred to Mulberry Grove as a “fragrant backwater.” He gave the letter to his parlormaid to post, and she forgot it and found it three weeks later in a drawer and burned it, and the editor would never have printed it, anyway, as it was diametrically opposed to the policy for which the Argus had always fearlessly stood, but—and this is the point we would stress—in describing Mulberry Grove as a fragrant backwater the major was dead right.

Mulberry Grove was a tiny cul-de-sac, bright with lilac, almond, thorn, rowan and laburnum trees. There were only two houses in it—Castlewood (detached) and a building of the same proportions next door, which some years earlier had been converted into two semi-detached residences, The Nook and Peacehaven. The other side of the road was occupied by a strip of ornamental water, with two swans on it—reading from left to right, Egbert and Percy. And the general effect of rural seclusion was completed by the fact that the back gardens of the houses terminated in the verdant premises of the Valley Fields Lawn Tennis Club. There was, in short, a pastoral charm about the place which—to quote Major Flood-Smith once again—made it absolutely damned impossible for you to believe that you were only seven miles from Hyde Park Corner—or, if a crow, only five.

Nothing marred the quiet peace of Mulberry Grove. No policeman ever came near it. Tradesmen’s boys, when they entered it on tricycles, hushed their whistling. And even stray dogs, looking in with the idea of having a bark at the swans, checked themselves.

The Biscuit was well pleased with the place.

“O. jolly K.,” he said to himself.

And, pausing for an instant to throw a banana skin at the swan Percy, who had stretched out his neck and was making a noise like an escape of steam and appeared generally to be getting a bit above himself, he passed on and came to a gate on which was painted in faded letters the word: Peacehaven.

Peacehaven was a two-story edifice in the Neo-Suburbo-Gothic style of architecture, constructed of bricks which appeared to be making a slow recovery from a recent attack of jaundice. Like so many of the houses in Valley Fields, it showed what Montgomery Perkins, the local architect, could do when he put his mind to it. It was he, undoubtedly, who was responsible for the two stucco sphinxes on either side of the steps leading to the front door.

WHERE nature had collaborated with Mr. Perkins, the result was more pleasing. A merciful rash of ivy had broken out over one half of the building, and a nice box hedge ran along the front fence. Substantial laurel bushes stood here and there, and there were flowers bordering the short snail walk which Mr. Cornelius would most certainly have described as a sweeping carriage drive.

To the right, shaded by a rowan tree, was a latticed door, leading apparently to the back premises. And the Biscuit, with a nature-lover’s eagerness to set his eye roaming over the parklike grounds, made for it immediately.

He passed through and, having passed, paused, not exactly spellbound but certainly surprised. Digging energetically in one of the borders with a spade not so very much smaller than herself was a girl.

Nothing in Mr. Cornelius’ conversation had prepared the Biscuit for girls in the parklike grounds.

“Hullo!” he said.

The digger ceased to dig. She looked up, and straightened herself.

“Hello!” she replied.

A man who has so recently become engaged to be married as Lord Biskerton has, of course, no right to stare appreciatively at strange girls. But this is what the Biscuit found himself doing. The fact that Ann Moon had accepted his hand had done nothing to impair his eyesight, and he could not fail to note that this girl was an exceptionally pretty girl. Her blue eyes were resting on his: and what the Biscuit felt was, as far as he was concerned, let the thing go on.

Something—perhaps the fact that she was a blonde and he a gentleman—seemed to draw him strangely to this intruder.

“Are you anybody special?” he asked. “I mean, do you go with the place?”

“Are you Mr. Smith?”

“Yes,” said the Biscuit.

“Pleased to meet you,” said the girl. Her voice had that agreeable intonation which he had noticed in a slighter degree in the voice of his betrothed.

“You’re American, aren’t you?” asked the Biscuit.

She nodded, and a bell of gold hair danced about her face. Very attractive the Biscuit—quite improperly—thought it. At the same time she made an observation which was neither “Yep,” “Yup,” nor “Yop,” but a musical blend of all three.

“I’ve just come over from America,” she said.

THIS was undoubtedly the moment at which the Biscuit should have been frank and candid. “Ah?” he should most certainly have remarked in a casual tone. “An odd coincidence. My fiancée is also American.”

Instead of which, he said:

“Oh? And how were they all?”

“I’m visiting with my uncle at Castlewood,” said the girl. “Over there,” she indicated with a sideways shake of the golden bell. “I came over the fence. Your garden looked awful. It hadn’t had a thing done to it in weeks, I should think. If there’s one thing that gives me the megrims, it’s a neglected garden. I’ve been trying to get it straight.”

“Frightfully good of you,” said the Biscuit. “The real Girl Guide spirit. I’m glad you like gardening. I fancy it’s going to be one of my hobbies. We must do a bit of spade and trowel work together.”

“You’re just moving in, aren’t you?”

“Yes. My things came down the day before yesterday. I expect old Berry has fixed them all up neatly by now. He said he would.”

“Berry?”

“Squire Conway. Of The Nook. His property marches with mine.”

“Oh? I haven’t met Mr. Conway.”

“Well, you’ve met me,” said the Biscuit. “Isn’t that enough of a treat for a small girl about half the size of a peanut?”

He paused. He perceived that he was allowing his tongue to run away with him. A newly-engaged man, conversing with blue-eyed girls, should be austerer, more aloof.

“Nice day,” he said, primly.

“Fine.”

“Making a long stay over here?”

“I shouldn’t wonder.”

“Capital!” said the Biscuit. “And what might the name be?”

“What name?”

“Yours, of course, fathead. Whose did you think I meant?”

“My name is Valentine.”

“And the Christian name, for purposes of informal chat?”

“Kitchie.”

“Caught cold?” asked the Biscuit.

“I was telling you my name. It’s Kitchie.”

Something of sternness crept into the Biscuit’s gaze.

“You needn’t think that just because I’ve got one of those engaging, open faces you can kid me,” he said. “I’m pretty intelligent, let me tell you, and I know the difference between a name and a sneeze. Nobody could possibly be called Kitchie.”

“Well, I am. It’s short for Katherine. What’s your first name?”

“Godfrey. Short for William.”

“Well,” said the girl, who during these conversational exchanges had been eying his upper lip with some intentness, “let me just tell you one thing: You ought to do something about that mustache of yours—either let it grow or cut it off. At present it makes you look like Charlie Chaplin. If you’ll excuse me being personal.”

“Replying to your remarks in the reverse order,” said the Biscuit, “be as personal as you desire. If two old buddies like us can’t be frank with each other, who can? In the second place, I see no harm in resembling Charlie Chaplin, a man of many sterling qualities whom I respect. Thirdly, I am letting it grow—in moderation and within due bounds. And, finally, the object under advisement is not a mustache, you poor Yank; it is a mustarsh. These points settled, tell me how you like England. Enjoying your visit, are you? Glad you came?”

“I like it all right. I wish I was back home, though.”

“Oh? Where’s that?”

“Great Neck, New York.”

“And you wish you were there?”

“I certainly do.”

“Why ‘certainly’?” asked the Biscuit, nettled. “What an extraordinary girl you must be. Here you are, having an absorbing conversation with one of the best minds in Valley Fields—and that best mind, mark you, wearing a new suit made by the finest bespoke tailor in London—and you say you wish you were elsewhere. Inexplicable! What is there so wonderfully attractive about Great Neck?”

Kitchie’s blue eyes clouded.

“Mer’s there,” she said.

“Ma? Your mother, you mean?”

“I didn’t say Ma. I said Mer. Merwyn Flock. The boy I’m engaged to. Dad got sore because Mer’s an actor, and he sent me over to England to get me away from him. Now do you understand?”

THE Biscuit understood. Yet, oddly, he was not pleased. To an engaged man the news that a golden-haired, blue-eyed girl he has just met is an engaged girl ought to be splendid news. It ought to make him feel that he and she belong to a great fellowship. He ought to feel like a brother hearing joyful tidings about a sister. Lord Biskerton felt none of these things. Utterly immersed though he was in a whole-hearted worship of his fiancée, the information that this girl before him was also betrothed made him feel absolutely sick.

“Merwyn Flock!” he said.

“You ought to hear Mer play the uke!”

“I don’t want to hear Mer play the uke,” said Lord Biskerton vehemently. “I wouldn’t listen to him playing the uke if you paid me. Merwyn! Ha!”

“That’s all right, you standing there saying ‘Merwyn’,” said Miss Valentine with equal warmth. “It’s a darned sight better name than that of Godfrey.”

It struck the Biscuit that he was allowing the tone of the conversation to become acrimonious.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Don’t let’s quarrel. Cheer up, half-portion, and let us speak of other things. Tell me your impressions of England. What’s it like living at Castlewood? Jolly? Festive?”

“Not so very. And I expected it would be a bigger place. When I was told I had an uncle living in a house called Castlewood, I thought it was going to be a sort of palace.”

“WELL, so it is. It’s got a summer house and a bird bath. What more do you want? And, if you’re disappointed, what about me? What’s become of the civic welcome I was entitled to expect? Where are the villagers?”

“What villagers?”

“I always understood that a chorus of villagers turned out on these occasions to welcome the new squire with dance and song. It won’t be long before I find myself believing that I have no seigniorial rights at all. How about that, by the way?”

“What about it?”

“Well, for one thing, as I came along here I noticed a sort of lake or mere across the road. Do I own the fishing? And the swanning, what of that? I shall most certainly want to have a pop at those swans with my bow and arrow very shortly.”

The girl was looking at him earnestly.

“You know,” she said, “when you talk quick, you remind me of Mer. His nose twitches like that.”

It was on the tip of Lord Biskerton’s tongue to say something so scathing and devastating about Mer that the friendship ripening between this girl and himself would have withered like a juvenile crocus in an early blizzard. At this moment, however, he perceived out of the corner of his eye that strange things were going on in Castlewood.

“I say,” he said, directing his companion’s attention to these phenomena, “there’s an extraordinarily ugly little devil in an eyeglass next door glaring and waving his hands at one of the windows.”

“That’s my uncle.”

“Oh? I’m sorry.”

“It isn’t your fault,” said the girl kindly.

The Biscuit surveyed the human semaphore with interest. “What is it? Swedish exercises?”

“I expect he wants me to come in. Now I remember, when I said I was thinking of coming over into your garden, he told me that I wasn’t on any account to stir a step till he had called on you and seen what you were like. I suppose I’d better go.”

“But I was just going to ask you to come in and see my little home. I expect there are all sorts of things in it that call for the feminine touch.”

“Some other day. Anyway, I’ve some letters to write. A girl I met on the boat has just got engaged, I see in the paper. I must write and congratulate her.”

“Engaged!” said the Biscuit gloomily. “It seems to me that the whole bally world is engaged.”

“Are you?”

“Me!” said the Biscuit, starting. “I say, I think you had better rush. Uncle seems to be hotting up.”

He stood where he was for a moment, admiring the nimble grace with which his small friend shinned over the fence. Then, pondering deeply, he made his way into the house to ascertain what sort of a dump this was into which Fate and his creditors had thrust him.

THAT night, smoking a friendly cigarette with his next-door neighbor, John Beresford Conway of The Nook, Lord Biskerton, somewhat to his companion’s surprise, spoke with warm approbation, rising at times to the height of enthusiasm, of the home life of the Mormon elder.

A Mormon elder, said the Biscuit, had the right idea. His, he considered, was the jolliest life on earth. He also stated that in his opinion bigamy, being, as it was, merely the normal result of a generous nature striving to fulfill itself, ought not to be punishable at law.

“And what you’ve got against Valley Fields, old boy,” he said, “is more than I can see. I don’t know when I’ve struck a place I liked more. I consider it practically a Garden of Eden, and you may give that statement to the press, if you wish, as coming from me.”

He then relapsed into a long and thoughtful silence, from which he emerged to utter a single word.

It was the word “Merwyn!”

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums