The Story Thus Far:

LEFT a vast fortune by his aunt—a lady who had most kindly adopted him and reared him in luxury—“Berry” Conway, a young Londoner, makes a painful discovery: Auntie’s “fortune” consists of worthless securities!

From an old school friend—the charming Godfrey, Lord Biskerton (“the Biscuit”)—he receives some sage advice, to wit: to sell the securities to the first buyer. . . . A grand suggestion! Berry proceeds to act on it. He is T. Paterson Frisby’s secretary. Mr. Frisby, an American financier, is president of The Horned Toad Copper Corporation. Berry tells him of a copper mine, “The Dream Come True,” which he owns.

Knowing “The Dream Come True” is—or may become—valuable, and that it is near his own property, Frisby wishes to buy it. But he makes no offer—merely tells Berry of one J. B. Hoke (his agent), who, he says, sometimes gambles on apparently worthless mines. After which he secretly tells Hoke to buy the mine for him.

At this dramatic juncture Mr. Frisby receives a surprise: Ann Moon, his beautiful niece, arrives from New York! A chaperon is needed, and the impecunious Lady Vera Mace, the Biscuit’s energetic auntie, lands the job.

Manna from heaven for the Biscuit! He promptly proposes to the new arrival—and their engagement is announced. The Biscuit’s father—the sixth Earl of Hoddesdon—is delighted. That gentleman, too, is—pardon the vulgarism—broke. But the Biscuit is worried. Creditors are harrying him. What to do to avoid being brought to court! Hah—an idea! . . . Wearing a huge black beard, he appears, and informs the amazed Lord Hoddesdon he is going to test his disguise. “You and Ann,” he announces, “are lunching at the Berkeley. I’ll be there. If she knows me, I’ll eat the whole outfit!”

III

WITH his usual masterful dash in the last fifty yards Berry Conway had beaten the 8:45 express into Valley Fields station by the split-second margin which was his habit. Alien though he felt the suburbs were to him, he possessed in a notable degree that gift which marks off suburbanites from other men—the uncanny ability always to catch a train and never to catch it by more than three and a quarter seconds. And, as those who race for early expresses to the city have sterner work to do en route than the observing of weather conditions, it was only after he had taken his seat and regained his breath and had leisure to look about him that he realized how particularly pleasant this particular day was.

It was, he perceived, a day for joy and adventure and romance. The sun was shining from a sapphire sky. Under its rays Herne Hill looked quite poetic. So did Brixton. And the river as he crossed it positively laughed up at him. By the time he reached Pudding Lane, he had come definitely to the conclusion that this was a morning which it would be a crime to waste cooped up in a stuffy office.

He had frequently felt like this before, but never had Mr. Frisby appeared to see eye to eye with him. Hard, prosaic stuff had gone to the making of T. Paterson Frisby. You didn’t find him flinging work to the winds and going out dancing Morris dances in Cornhill just because the sun happened to be shining. As a rule, it was precisely these magic mornings of gold and blue that seemed to stimulate the old buzzard to perfectly horrid orgies of toil. “C’mon now!” he would say, eying a sunbeam as if it wanted to borrow money from him, and on Berry would have to come.

But miracles do happen, if one is patient and prepared to wait for them. Just as Berry had finished sorting as dull a collection of letters as ever offended a young man’s sensibilities on a glowing summer day, the door was flung open and there came in something so extraordinarily effulgent that he had to blink twice before he could focus it.

It was not merely that T. Paterson Frisby was wearing a suit of light gray flannel. It was not even the fact that he had a Panama hat on his head and a Brigade of Guards tie round his neck that stupefied the observer. The really amazing thing about him was his air of radiant bonhomie. The man seemed positively roguish. He had gone gay. As Berry stared at him dumbly, a sort of spasm passed over T. Paterson Frisby’s face, causing a hideous distortion. It was a smile.

“ ’Morning, Conway!”

“Good morning, sir,” said Berry.

“Anything in the mail?”

“Nothing of importance, sir.”

“Well, leave it all till tomorrow.”

“Till tomorrow?”

“Yes. I’m off to Brighton.”

“Yes, sir,” Berry answered quickly.

“You can take the day off.”

“Thank you very much, sir,” said Berry.

HE was stunned. Such a thing had never happened before. Not once in the whole course of his association with Mr. Frisby had there ever been even the suggestion of such a thing. He could hardly believe that it was happening now.

“Got to start right away. Motoring. Shan’t be back till this evening. Two things I want you to do. Go to Mellon and Pirbright in Bond Street and get me a couple of aisle seats for some good show tonight. Put them down to my account and have them sent to my apartment.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Tell them I want something good. They know what I’ve seen. And then go on to the Berkeley and book me a table for supper.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Table for two. Not too near the band.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Right. By the way, I knew there was something. I saw that man Hoke last night. I told him about that mine of yours. He’s interested.”

A thrill shot through Berry.

“Is he, sir?”

“Yes. Oddly enough, he happens to know that particular property. Will you be in this evening?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’ll tell him to run down and see you. Between ourselves, don’t let him know I told you—he will go to five hundred pounds.”

“He will!”

“He told me so. He was going to have tried for less, but I said that that was your lowest figure. So, if you’re satisfied, he’ll bring down all the papers and you can get the thing settled tonight. And I won’t charge you agent’s commission,” said Mr. Frisby, chuckling like a Cheeryble Brother.

Berry blinked. Exquisite remorse racked him when he thought that not once but several times in his private reflections he had labeled this golden-hearted man a dish-faced little slave-driver. He saw him now for what he was—an angel in disguise.

“I’m most awfully obliged, sir,” he stammered.

“You’re welcome.”

“You really think he will give me five hundred pounds?”

“I know he will. Well, that’s all. ’Morning,” said Mr. Frisby, and took his departure. It was as if both Cheeryble Brothers had left the office arm-in-arm.

For some moments after he had gone Berry remained motionless. Motionless, that is to say, as far as his limbs were concerned. His brain was racing tempestuously.

Five hundred pounds! It was the key to life and freedom. Attwater’s loan—he could repay that. The Old Retainer—he could fix her up so that she would be all right. And, when these honorable duties were performed, he would still have something in pocket to start him off on the path of adventure.

He drew a deep breath. In body he was still in his employer’s office, but in spirit he was making his way through the streets of a little sun-baked town that lay in the shadow of towering mountains. And as he passed along the natives nudged one another, awed.

“There he goes,” they were saying. “See that man? Hardcase Conway! They don’t come any tougher.”

IT WAS getting on for lunchtime when Berry, having completed the purchase of the theater tickets, sauntered from the emporium of the Messrs. Mellon and Pirbright into the rattle and glitter of Bond Street once more.

The day seemed now to have touched new heights of brilliance. There was sunshine above and sunshine in his heart. A magic ecstasy thrilled the air. He gazed upon Bond Street, fascinated.

To the blasé man about town and the jaded boulevardier, Bond Street at one o’clock in the afternoon at the height of the London season is just Bond Street. But to a young man with romance in his soul, an unexpected holiday on his hands and the prospect of freedom and adventure gleaming before him, it is Main Street, Bagdad. The feeling of being in the center of things intoxicated Berry.

It was his practice, when walking in London, to look hopefully about him on the chance of exciting things happening. Nothing of the slightest interest had ever happened yet, and he had sometimes felt discouraged. But Bond Street restored his optimism. This, he felt, was a spot where anything might occur at any moment.

Here, if anywhere, he said to himself, might beautiful women in slinky clothes sidle up to a man and slip into his hand the long envelope containing the Naval Treaty stolen that morning from a worried Foreign Office, mistaking him—on the strength of the carnation in his buttonhole—for Flash Alec, their accomplice. Whereas in Threadneedle Street or Valley Fields you might hang about all your life without drawing so much as a picture postcard.

Up and down the narrow street expensive automobiles were rolling, and the pavements were full of expensive-looking pedestrians. One of these had just elbowed Berry toward the gutter, when he became aware that a two-seater had stopped beside him. The next moment its occupant was addressing him in a strong foreign accent:

“Pardon me, but is it that you could dee-reckut me to Less-ess-ter Sker-vare?”

Berry looked up. It was not an exotically perfumed woman. It was a rather shocking-looking bounder with prominent eyebrows and a black beard of amazing proportions.

“Leicester Square?” he said. “You turn to the left and go across Piccadilly Circus.”

“I tank you, sare.”

Berry stood staring after the car. The man had excited him. True, he had said nothing to suggest that he was not a perfectly respectable citizen, but there was something about him that gave one the idea that his pockets were simply bulging with stolen treaties. So Berry stood, gaping, and might have stood indefinitely, had not a hungry pedestrian, hurrying to his lunch, butted him in the small of the back.

Jerked into the world of practical things again by this shock, he made his way to the Berkeley to order Mr. Frisby’s supper table.

Mr. Frisby was evidently a popular customer at the Berkeley. The mention of his name aroused interest and respect. A head-waiter who looked like an Italian poet assured Berry that all would be as desired. A table for two, not too near the band. Correct.

He then inquired with a charming deference if Berry proposed to take luncheon at the restaurant, indicating temptingly a small table at his side. And Berry was about to reply that such luxuries were not for him, when, turning to look wistfully at the table, he saw a sight that struck the words from his lips.

The bearded bounder was sitting not six feet away, tucking into smoked salmon.

Only for an instant did Berry hesitate. For a man of his straitened means lunch at a place like this would be a bold, one might almost say a reckless, and a devil-may-care adventure. It would hit the privy purse one of the nastiest wallops it had received for many a long day. But Fate had gone out of its way to send him this Man of Mystery, and it would be making a churlish return for Fate’s amiability if he were to reject him on the pusillanimous grounds of economy.

The man intrigued him. Obviously, he was a suspicious character. Nobody who wasn’t would parade London in a beard like that. Moreover, after being definitely instructed to turn to the left and go across Piccadilly Circus, he had turned to the right and gone to the Berkeley. If that wasn’t sinister, what was?

He sat down, and a subordinate waiter swooped on him with the bill-of-fare.

The bearded man was now eating some sort of fish with sauce on it. And Berry, watching him intently, became gripped by a suspicion that grew stronger each moment. That beard, he could swear, was a false one. It was so evidently hampering its proprietor. He was pushing bits of fish through it in the cautious manner of an explorer blazing a trail through a strong forest. In short, instead of being a man afflicted by nature with a beard, and as such more to be pitied than censured, he was a deliberate putter-on of beards, a self-bearder, a fellow who, for who knew what dark reasons, carried his own private jungle around with him, so that at any moment he could dive into it and defy pursuit. It was childish to suppose that such a man could be up to any good.

The bearded man was now eating some sort of fish with sauce on it. And Berry, watching him intently, became gripped by a suspicion that grew stronger each moment. That beard, he could swear, was a false one. It was so evidently hampering its proprietor. He was pushing bits of fish through it in the cautious manner of an explorer blazing a trail through a strong forest. In short, instead of being a man afflicted by nature with a beard, and as such more to be pitied than censured, he was a deliberate putter-on of beards, a self-bearder, a fellow who, for who knew what dark reasons, carried his own private jungle around with him, so that at any moment he could dive into it and defy pursuit. It was childish to suppose that such a man could be up to any good.

And then, as if to confirm this verdict, there suddenly occurred a scene so suggestive that Berry quivered as he watched it.

Into the restaurant there had just strolled a distinguished-looking man of about fifty, stroking a becoming gray mustache. He spoke to the head-waiter, evidently ordering a table. Then, as he turned to go back to the anteroom where hosts at the Berkeley await their guests, his eye fell on the bearded man.

He started violently, stared as if he had seen some horrible sight, as indeed he had, and crossed to where the other sat. A short conversation ensued, during which he appeared to be expostulating. Then, plainly shaken, he tottered out.

BERRY leaned forward in his seat, thrilled. He had placed the bearded man now. He saw all. Quite obviously this must be The Sniffer, the mysterious head of the great Cocaine Ring which was causing Scotland Yard so much concern. As for the gray-mustached one, he would be an accomplice in high places, a baronet of good standing, or perhaps a well-thought-of duke, on whose reputation no suspicion of wrongdoing had ever rested. And his unmistakable agitation must have been caused by the shock of meeting The Sniffer in a place like this where his beard might come unstuck at any moment and betray him.

BERRY leaned forward in his seat, thrilled. He had placed the bearded man now. He saw all. Quite obviously this must be The Sniffer, the mysterious head of the great Cocaine Ring which was causing Scotland Yard so much concern. As for the gray-mustached one, he would be an accomplice in high places, a baronet of good standing, or perhaps a well-thought-of duke, on whose reputation no suspicion of wrongdoing had ever rested. And his unmistakable agitation must have been caused by the shock of meeting The Sniffer in a place like this where his beard might come unstuck at any moment and betray him.

“Go back to the underground cellar in Limehouse, where you are known and respected,” he had probably whispered feverishly. And The Sniffer, jeering—Berry had distinctly seen him jeer—had replied that he had already started his lunch and so would have to pay for it, anyway, and, risk or no risk, he was dashed if he intended to leave before he had had his eight bobs’ worth.

Upon which the other, well knowing his chief’s stubbornness, had given up the argument and gone out, practically palsied.

The day dream was shaping well, and, had nothing occurred to interrupt it, would probably have continued to shape well. But a moment later all thoughts of The Sniffer had been driven from Berry’s mind. The gray-mustached man had reëntered the room, and this time he was not alone.

Walking before him, like a princess making her way through a mob of the proletariat, came a girl. And at the sight of her Berry’s eyes swelled slowly to the size of golf balls. His jaw dropped, his heart raced madly and a potato fell from his trembling fork.

For it was the girl he had been looking for all his life—the girl he had dreamed of on summer evenings when the western sky was ablaze with the glory of the sunset or on spring mornings when birds sang their anthems on dewy lawns. He recognized her immediately. For a long time now he had given up all hope of ever meeting her, and here she was—exactly as he had always pictured her on moonlight nights when fiddles played soft music in the distance.

He sat staring, and when the waiter broke in upon this holy moment to ask him if he would like a little cheese to follow found some difficulty in maintaining the Conways’ high standard for courtesy.

In staring at Ann Margaret, only child of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas L. Moon of New York City, Berry Conway had no doubt been guilty of a breach of decorum. But it was a breach of which many, many young men had been guilty before him. Ann Moon was the sort of girl at whom young men in restaurants have to summon all their iron will to keep from staring.

We have seen what the knowledgeable editor of the Mangusset Courier-Intelligencer thought of Ann, and it may be stated now officially that his description erred, if at all, on the side of restraint and understatement. Possibly through pressure of space, he had omitted one or two points on which he might well have touched and on which, to present the perfect portrait, he should have touched. The dimple in her chin, for instance, and the funny way in which that chin wiggled when she laughed. Still, in the matter of the wondrous fascination and the remarkable attractiveness and the disposition as sweet as the odor of flowers, he was absolutely right. Berry had noticed these at once.

Lord Hoddesdon had noticed them, too, and once again there crossed his mind a feeling of dazed astonishment that a girl like this, even under the influence of Edgeling Court in the gloaming, could ever have accepted that son of his who was now sitting two tables away crouched behind his zareba of beard.

However, the main thing on which he was concentrating his mind at the moment was the problem of how to keep Ann’s share of the luncheon down to a reasonable sum. If he could only head her off any girlish excesses in the way of drinks and coffee, the exchequer, as he figured it out, would just run to a cigar and liqueur, for both of which he had a strong man’s silent yearning.

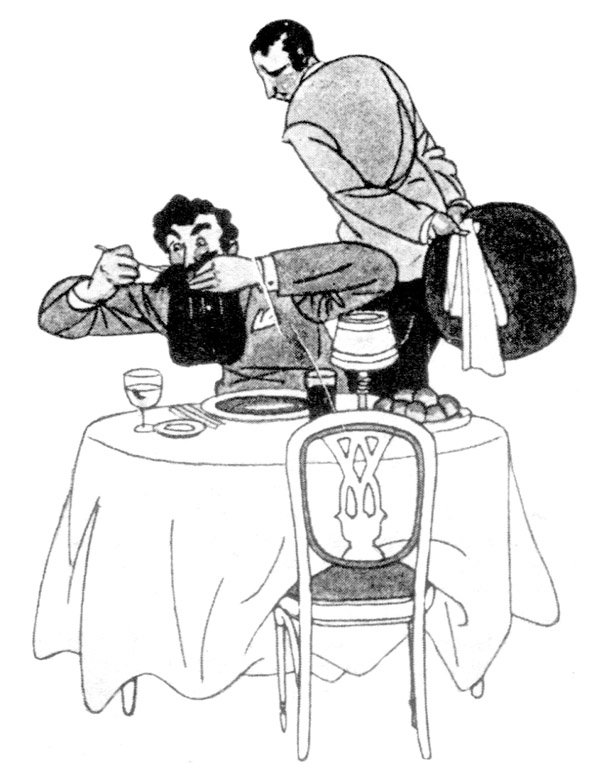

“Something to drink, my dear?” he said, as the waiter approached and hovered.

Ann withdrew her gaze from the middle distance.

“No, thanks. Nothing.”

“Nothing,” said Lord Hoddesdon to the waiter, trying not to sing the word.

“Vichy?” said the waiter.

“Nothing, nothing.”

“St. Galmier? Tonic water? Evian?”

“No, thank you. Nothing.”

“Lemonade?” said the waiter, who was one of those men who never know when to stop.

“Yes, I think I would like a lemonade,” said Ann.

“I wouldn’t,” advised Lord Hoddesdon earnestly. “I wouldn’t, honestly. Bad stuff. Full of acidity.”

“All right,” said Ann. “Just some plain water, then.”

“Just,” said Lord Hoddesdon, looking the waiter dangerously in the eye, “just some plain water.”

HE BESTOWED upon his future daughter-in-law the affectionate smile of a man who is two shillings ahead of the game. Charming, he felt, to find a girl nowadays who did not ruin her complexion and digestion with cocktails and wines and what not.

The smile was wasted on Ann. She did not observe it. She was looking out across the room again. The noise of music and chattering came to her as from a distance. Her father-in-law-to-be on the other side of the table seemed very far away. Once more she had become occupied with the train of thought which this discussion of beverages had interrupted. Ever since she had read in her paper that morning the plain, blunt statement that she was engaged to be married she had been feeling oddly pensive.

There is about the printed word a peculiar quality which often causes it to exercise a rather disquieting effect on the human mind. It chills. It was only after seeing that announcement set forth in cold type that Ann had come to a full realization of the extreme importance of the step she was about to take and the extreme slightness of her acquaintance with the man with whom she was going to take it.

A sudden thirst for information seized her. She leaned toward her host.

“Tell me about Godfrey,” she said abruptly.

“Eh?” said Lord Hoddesdon, blinking. He, too, had been busy with his thoughts. He had been speculating as to the odds on and against the girl’s wanting coffee and wondering how a well-judged word about it being bad for the nerves would go. “What about him?”

IT WAS a question which Ann found difficult to answer. “What sort of man is he?” she would have liked to say. But when you have agreed to marry a man, it seems silly to ask what sort of a man he is.

“Well, what was he like as a little boy?” she said, feeling that that was safe. Indeed, the words had a rather pleasantly naïve and fiancée-like ring.

Lord Hoddesdon endeavored to waft his memory over scenes which he had always preferred to forget.

“Oh, the usual grubby little brute,” he said. “I mean, of course,” he added hastily, “very charming and lively and—er—boyish.”

He perceived that he had been within an ace of allowing his heart to rule his head.

“Boyish and vivacious,” he proceeded. “Full of spirits. But always,” he said impressively, “good.”

“Good?” said Ann with a slight shiver.

“Always the soul of honor,” said Lord Hoddesdon solemnly.

Ann shivered again. Clarence Dumphry had been the soul of honor. She had often caught him at it.

“Neither during his boyhood nor since,” went on Lord Hoddesdon, warming to his work and finding the going less sticky as he got into his stride, “has he ever given me a moment’s anxiety.” He glanced over his shoulder with a sudden nervous movement, as if expecting to see the Recording Angel standing there with pen and notebook. Relieved at discovering only a waiter, he resumed. “He was never one of those young men who go about dancing half the night with chorus girls and so forth,” he said. “I don’t think he ever gambled, either.”

“You don’t know that,” said Ann, refusing to abandon hope.

“Yes, I do,” replied Lord Hoddesdon glibly. “Now I come to think of it, I asked him once, and he told me he didn’t. If he had been in the habit of gambling, he would have said ‘Yes, Dad.’ That has always been his way—frank and manly. Whatever I asked him, it would be ‘Yes, Dad’ or ‘No, Dad,’ looking me straight in the face. I remember once,” said Lord Hoddesdon, going off the rails a little, “he smeared jam all over my chair in the library.”

“He did?” said Ann, brightening.

“Yes,” said Lord Hoddesdon. “But,” he went on, recovering himself, “he came straight to me and looked me in the face and said ‘Dad, it was I who put that jam on your chair in the library. I’m sorry. I felt I had to tell you because otherwise somebody else might have been suspected.’ ”

“How old was he then?”

“About ten.”

“And he really said that?”

“He really did.”

“And he’s like that now?”

“Just like that,” said Lord Hoddesdon doggedly. “A real, true-blue English gentleman, honorable to the core.”

Ann winced slightly and returned to her reflections. She was thinking now about Edgeling Court and not too cordially.

In attributing to the glamour of the family’s ancestral seat his fiancée’s acceptance of his proposal of marriage, Lord Biskerton had shown penetration. Edgeling Court had had quite a good deal to do with it. Its Old World charm, Ann was thinking, had undoubtedly weakened that cool, clear judgment on which she had always prided herself—that heaven-sent gift of level-headed criticism which enables girls to pass unscathed among the Clarence Dumphrys of this world. Those bees and doves and rooks, she realized, had conspired together to sap her defenses, and here she was engaged to be married to a true-blue English gentleman.

Ann pulled herself together. She told herself that she must not believe everything she heard. Quite likely Lord Biskerton had never really been a true-blue English gentleman. She had only his father’s word for it. And, if he had been, it was quite possible that he had got over it. She liked him, she assured herself. He amused her. He made her laugh. They would be very happy together—very, very, very happy.

ALL the same she wished that he was not quite such a total stranger. She felt doubtful and disturbed—rather like a young author who has just put his signature to a theatrical manager’s contract and is wondering if all is quite well concerning that clause about the motion-picture rights.

“You’re very quiet, my dear,” said Lord Hoddesdon.

Ann started.

“I’m so sorry. I was thinking.”

Lord Hoddesdon wavered on the brink of something about lovers’ reveries, but decided not to risk it.

“This chicken’s good,” he said, choosing a safer subject.

“Yes,” said Ann.

“You will have a sweet after this?”

“Yes, please.”

“And about coffee,” said Lord Hoddesdon. A grave look came into his clean-cut face. “I don’t know how you feel about coffee, but I always maintain that, containing, as it does, an appreciable quantity of the drug caffeine, it is a thing best avoided. Bad for the nerves. All the doctors say so.”

“I don’t think I will have any coffee. As a matter of fact, I would like to go directly I have finished the sweet. If you don’t mind my leaving you?”

“My dear girl, of course not. Not at all. I will just sit here and listen to the music. I may possibly have a cigar and a liqueur. Got some shopping to do?”

“No—but it’s such a lovely day I rather wanted to go for a run in my car. I’ve got it outside. I thought I would go down to the river somewhere.”

“Streatley is a charming spot. Or Sonning.”

“I somehow feel as if I want to get away and think today.”

“I understand,” said Lord Hoddesdon paternally. “Naturally. Well, don’t you bother about me. I’ll just sit. I like sitting.”

Ann smiled, and looking out across the room again immediately found her eye colliding with that of the young man in brown at the table by the wall—the seventh time this had happened since her arrival.

There were two reasons why Ann Moon, sitting where she did, should have caught Berry Conway’s eye so frequently. One was that when she looked up she had to look in his direction, because in the only other possible direction there was seated a bearded man of such sinister and revolting aspect that, whenever her gaze met his, she recoiled as if she had touched something hot. And he was not only most unpleasant to look at, but in an odd way he reminded her the tiniest little bit of her betrothed, Lord Biskerton, and she found this disturbing.

THE other reason was that, rebuke herself for the weakness though she might, she liked catching Berry’s eye. The process definitely gave her pleasure. His eye seemed to her an interesting eye. It had, she noted, a kind of odd, smoldering, hungry sort of gleam in it—a gleam that might have been described as yearning. It was novel to her. None of the men she had met had ever had yearning gleams in their eyes. Clarence Dumphry, the well-known stiff, hadn’t. Nor had the Burwash boy. Nor, for that matter, had Lord Biskerton. And it was a gleam she liked.

He intrigued her, this lean, slim young man with his keen face and fine shoulders. He had the air, she thought, of one who did things. He somehow suggested brave adventures. She could picture herself, for instance, trapped in a burning house and this young man leaping gallantly to the rescue. She could see herself assailed by thugs and this young man felling them with a series of single blows. That was the sort of man he seemed to her.

She wished she knew him.

Berry, at his table, was wishing even more heartily that he knew her. If his eye gleamed yearningly, it had every reason to do so. He was regretting passionately that Fate, having planned that he should feel about a girl the extraordinary flood of mixed emotions which were now making him dizzy, had not arranged that he should feel them about some girl with whom he might conceivably at some time become acquainted.

It was quite evident to him by now that he had happened upon the one member of the opposite sex who might have been constructed from his own specifications. If all the arrangements had been in his personal charge, there was not the smallest alteration which he would have made. Those eyes; that small, provocative nose; those teeth; that hair; those hands. . . . They were all exactly right.

And for all the chance he had of ever getting to know her they might be on different planets.

Ships that pass in the night . . .

She was leaving now. So, as a matter of fact, was the bearded man. But Berry had ceased to waste thought on him. The bearded man had been eliminated by the pressure of competition. By this time he was to Berry just a bearded man, if that.

It seemed to Berry that he might as well be leaving, too. He called for his bill, and tried not to wince at the sight of it.

OUT in the sunshine Ann walked pensively toward her two-seater. She had parked it up near the Square. The bearded man had parked his somewhere up there, too, it appeared, for he now passed her, giving her, as he went, a swift, strange, sinister look. The resemblance to Lord Biskerton was even more striking than it had been at a distance in the restaurant. Seen close to, he might have been Lord Biskerton’s brother who had gone to the bad and taken to growing beards.

The sight of him gave Ann a guilty feeling. In thought, she realized, she had not been altogether true to her Godfrey. She found, examining her soul, that she had been comparing him to his disadvantage with that strong, romantic-looking young man in brown, whose eye had seemed so yearning and who now, as she settled down at the wheel of her two-seater, jumped abruptly in beside her and in a voice that electrified every vertebra in her spine whispered hoarsely:

“Follow that car!”

In addition to galvanizing her spine, this polite request had had the effect of causing Ann to bite her tongue. It was with tear-filled eyes that she turned, and in a voice thickened with anguish that she replied.

“Wock car?” asked Ann.

Berry did not reply immediately. His emotions at the moment were those of one who has just jumped into a pool of icy water and is trying to get used to it. He was still endeavoring to convince himself that it was really he who had behaved in this remarkable manner. Such is often the effect of acting upon impulse.

“Wock car?” said Ann.

Berry pulled himself together. He had started something, and he must go on with it.

“That one,” he said, pointing.

He would have been amazed had he known that his companion was thinking what an attractive voice he had. To his ears, the words had sounded like the croak of an aged frog.

“The one with the bearded man in it?” said Ann.

“Yes,” said Berry. “Follow him wherever he goes.”

“Why?” said Ann.

It is proof that she was no ordinary girl that she had not begun by asking this question.

BERRY had not spent much of his valuable time in brooding on the bearded man for nothing. His answer came readily:

“He’s wanted.”

“Who by?”

“The police.”

“Are you a policeman?”

“Secret Service,” said Berry.

Ann stepped on the accelerator. The sun was shining. The birds were singing. She had never felt so happy and excited in her life.

It charmed her to think that her long-range estimate of this young man had not been at fault. She had classed him on sight as one who lived dangerously and dashingly, and she had been right.

She quivered from head to foot, and her chin wiggled. At last, felt Ann, she had met somebody different. . . .

Godfrey, Lord Biskerton, was also feeling in the pink.

“Tra-la!” he caroled as he steered his car into Piccadilly, and “Tum tum ti-umty-tum” he chanted, turning southward at Hyde Park corner. He was filled with the justifiable exhilaration which comes to a man who has made a great and momentous experiment and has seen that experiment not only come off but prove an absolute riot from start to finish.

In risking the trial trip of his beard and eyebrows (by Clarkson) at such a familiar haunt of his as the Berkeley, the Biscuit had known that he was applying the acid test. If nobody recognized him there, nobody would recognize him anywhere. Apart from the fact that he would be sitting in the midst of a platoon of his intimates, most of the waiters knew him well. In fact, the head-waiter had always treated him more like a younger brother than a customer.

And what had happened? Neither Ferraro nor any of his assistants had shown in his manner the slightest suggestion of Auld Lang Syne. They might have been saying to themselves, “Ha! A distinguished, bearded stranger!” They had certainly not been saying to themselves, “Well, well! What a peculiar appearance jolly old Biskerton has today!” Not one of them had spotted him. He had passed the scrutiny with honors.

And Ann. He had given her every opportunity. He had stared meaningly at her in the restaurant, and he had passed within a foot of her when going to de-park his car. But she, too, had failed to penetrate his disguise.

And old Berry. That, he reflected complacently, had been his greatest triumph. “Is it that you could dee-reckut me to Less-ess-ter Sker-vare?” Right in the open, face to face. And not a tumble out of the man.

TO SUM up, then. If all these old friends and acquaintances had been utterly unable to recognize him, what hope was there for the bloodsuckers with their judgment summonses—for Jones Bros., Florists, twenty-seven pounds, nine and six, or for Galliwell and Gooch, Shoes and Bootings, thirty-four, ten, eight?

A great relief stole over Lord Biskerton. Thanks to this A-1 beard and these tried and tested eyebrows, he would be able to remain in London and go freely and without fear about his lawful occasions. Until this afternoon he had doubted whether this were possible. There had been pessimistic moments when he had seen himself having to fly to Bexhill or take cover in Wigan.

For the rest it was a lovely day, the car was running sweetly and if he stepped on the gas a bit he would just be able to get to Sandown Park in time for the three-o’clock race. He knew something pretty juicy for the three o’clock at Sandown and, thank heaven, there were still a brace or so of bookies on the list who, though noticeably short on Norman blood, fully made up for the deficiency by that simple faith which the poet esteems so much more highly.

By the time he reached Esher the Biscuit was trolling a gay stave. And it was as he approached the Jolly Harvesters, licensed to sell wines, spirits and tobacco, that there floated into his mind the thought that what the situation called for was a beaker of the best.

He put the brakes to the two-seater and went in.

Printer’s error corrected above: Magazine, p. 17b, had “Valley Felds”.

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums