Grand Magazine, September 1924

CHAPTER I

a marriage has been arranged

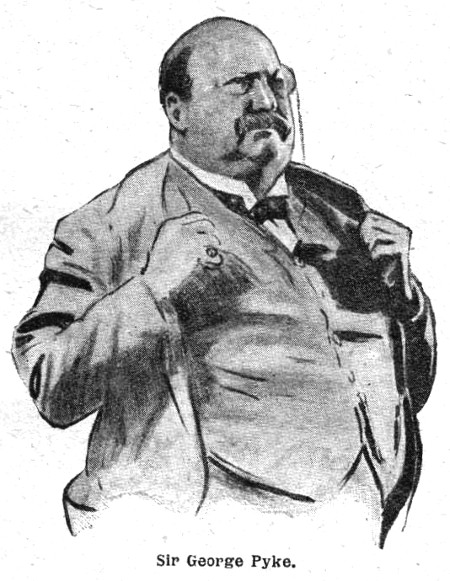

IT is the custom nowadays to describe all successful men who are stumpy and about twenty pounds overweight as Napoleonic. But, hackneyed though the adjective is, it must be admitted that there was indeed something suggestive of Napoleon in the port of Sir George Pyke as he strode up and down his office. His generously-filled waistcoat and the habit he dropped into in moments of meditation of thrusting the fingers of his right hand in between its first and second buttons gave at any rate a superficial resemblance to the great Corsican—and this resemblance was accentuated by the gravity of his plump, determined face. He looked like a man fond of having his own way: nor in the last twenty years of his life had he often failed to get it.

The desk-telephone emitted a discreet buzzing sound, as if it shrank from raising its voice in the presence of such a man.

“Mrs. Hammond to see you, Sir George.”

“Send her in, send her in. Good heavens, Francie!” exclaimed the proprietor of the Mammoth Publishing Company as the door opened, “I’ve been ’phoning your house half the morning, trying to get hold of you.”

“How fortunate that I happened to look in!” said Mrs. Hammond, settling herself in a chair. “What is it?”

Frances Hammond, née Pyke, was a feminine replica of her eminent brother. She lacked his second chin, but had the same bright and compelling eyes, the same over-jutting brows which lent those eyes such keenness, the same high colouring and breadth of forehead.

“What did you want to see me about?” asked Mrs. Hammond.

Sir George drew a deep breath. He had tremendous news to impart, and an instinct for drama urged him not to spoil this great moment by blurting the secret out too abruptly. But ecstasy was too strong for his sense of the dramatic.

“Francie, old girl,” he cried, “what do you think? They’ve offered me a peerage!”

“Georgie!”

Mrs. Hammond scrambled out of her chair and kissed her brother fondly. There were tears in her commanding eyes.

“I thought it would please you.”

“I am proud of you, Georgie dear! What a culmination for your splendid career!”

“And who helped me build that career? Hey?”

“I have always done what I could,” said Mrs. Hammond modestly. “But of course it was you——”

Sir George thumped the desk; and, happening to strike the sharp edge of a wire paper-basket, wished that he had expressed his emotion a little less muscularly. He sucked his hand for a moment before speaking.

“You have been the making of the business,” he said, vehemently, when the pain had somewhat abated. “I couldn’t have got anywhere without you. Who suggested the How Many Pins Does the Prime Minister’s Hat Hold competition in Pyke’s Weekly when it was touch-and-go if it could turn the corner? From that moment Pyke’s Weekly never looked back. And on Pyke’s my whole present fortune is founded. The fact is, from the very start we have worked as a team. If I had the ginger, you had the judgment. I don’t suppose there’s a person in the world whose judgment I respect as highly as I do yours, Francie.”

Mrs. Hammond beamed.

“Well, Georgie, I’m sure I’m only too glad if my efforts to play Egeria have been successful.”

“Play what?” said Sir George, looking a trifle blank.

“Egeria was a goddess who helped and inspired the Roman king Numa Pompilius. At least, so Sinclair tells me.”

She referred to Mr. Sinclair Hammond, the well-known archæologist, who enjoyed the additional distinction of being her husband.

“Now there’s a fellow,” said Sir George, “who, if he had a little drive and initiative, would go far. Plenty of brains.”

Mrs. Hammond forbore to discuss her husband. She had grown used to his dreamy lack of ambition, his undynamic acceptance of his niche in the world.

“What title did you think of adopting, Georgie?” she asked, changing the subject.

Sir George, whose great brain never wholly relaxed even in its social moments, was speaking into the dictaphone.

“Editor, Pyke’s Weekly, attention,” he was saying. “Article next week on Famous Women Who Have Inspired Famous Men. You know—Egeria and so forth.” He turned away apologetically. “I beg your pardon?”

“I said, have you thought of a title yet?”

“Just jotted down a few suggestions, that’s all.” He picked up a pad. “How do you like Lord Barraclough? Or Wensleydale? Or Marlinghue? The one that pleased me most was Michelhever. There’s a swing about Michelhever.”

Mrs. Hammond shook her head.

“Too florid. They’re all too florid.”

“Well, you know, a title ought to have a bit of a ring. Look at some of the ones there are already—Beaverbrook—Stratheden—Leverhulme. Plenty of zip to them!”

“I know. But none of these you have mentioned sound just right to me. There is nothing actually wrong with them, and a man with your personality could carry them off; but they are all just the least bit ornate. You must not forget that eventually Roderick will have to succeed to whatever title you choose. We must not select anything that would seem ridiculous in connection with Roderick. His actual name is bad enough, as it is. Roderick!”

The frown which had been so long absent from Sir George’s happy face returned, blacker than ever. He had the air of one into whose cup of joy an unfriendly hand has dropped a dead mouse.

“I’d forgotten all about Roderick,” he said, moodily.

THERE was a pause. The future Lord Michelhever (or possibly Wensleydale or Marlinghue) drummed irritably on the desk with his finger-tips.

“How the deuce I came to have a son like that,” he complained, as many a stout father had done before him and many would do when he was dead and gone, “beats me!”

“He takes after poor Lucy,” said Mrs. Hammond. “She was just the same timid, feeble creature.”

Sir George nodded. The mention of his long-departed wife stirred no sentimental chord in him. The days when he was plain George Pyke, humble clerk in a solicitor’s office, and used to thrill at the soft voice of Lucy Maynard as she took the order for his frugal lunch at the Holborn Viaduct Cabin had long since faded from his memory.

“Reminds me,” said Sir George, reaching for the telephone, “that I want to have a word with Roderick. I’ll do it now,” he said, unconsciously quoting the motto which by his instructions had been placed in a wooden frame on every editorial desk in the building. “I rang up the Spice office just before you came, but he was still out at lunch.”

“Wait one moment, Georgie. There is something I want to speak to you about before you send for Roderick.” Sir George, always docile when it was she who commanded, put down the telephone. “What has he been doing that you want to see him?”

Sir George snorted.

“I’ll tell you!” The agony of a disappointed father rang in his voice. In some such accents might King Lear have spoken of his children. “I gave that boy his head far too much while he was up at Oxford. I let him have a large allowance, and what did he do with it? Published a book he had written on the Prose of Walter Pater! At his own expense in limp purple leather! And on top of that had the effrontery to suggest that the Mammoth should take over the Poetry Quarterly, a beastly thing that doesn’t sell a dozen copies a year, and let him run it as editor.”

“I know all that,” said Mrs. Hammond, a shade impatiently. If Georgie had a fault, it was this tendency of his towards the twice-told tale. “And you made him editor of Society Spice. How is he getting on?”

“That’s just what I’m coming to. I started to break him into the business by making him editor of Spice, never dreaming that even he could make a mess of that. Why the position is a sinecure. Young Pilbeam, a thoroughly able young fellow, really runs the paper. All I asked of Roderick, all I wanted him to do, was to show some signs of Grip and generally find his feet before going on to something bigger. And what happens? Young Pilbeam tells me that Roderick deliberately vetoes and excludes from the paper all the best items he submits. That’s his idea of earning his salary and being loyal to the firm that employs him!”

Mrs. Hammond clicked her tongue concernedly.

“But what possible motive could he have?”

“Motive? A boy like that doesn’t have to have motives. He’s just a plain imbecile. I wish to Heaven,” cried this tortured parent, “that he would get married. A wife might make something of him.”

Mrs. Hammond started.

“What an extraordinary thing that you should say that! It was the very thing I wanted to speak to you about. I suppose you realise, George, that, now you are going to receive this peerage, Roderick’s marriage becomes a matter of vital importance? I mean, it is even more essential than before that he should marry somebody in a suitable social position.”

“Let me catch him,” said Sir George, grimly, “trying to marry anybody that isn’t!”

“Well, you know, there was that girl you told me about—the one that worked as a stenographer in the Pyke’s Weekly office.”

“Sacked,” said Sir George briefly. “Shot her out five minutes after I discovered that they were having a flirtation.”

“Has he been seeing her since?”

“Wouldn’t have the nerve to.”

“No, that is true. Deliberate defiance of your wishes would be out of keeping with Roderick’s character. Has he shown any signs of being attracted by any other girl? Any girl in his own class, I mean?”

“Not that I know of.”

“George,” said Mrs. Hammond, leaning forward, “I have been thinking of this for some time. Why should not Roderick marry Felicia?”

SIR GEORGE quivered from head to foot. He gazed at his sister with that stunned reverence which comes over men whose darkness has suddenly been lightened by the beacon-flash of pure genius. This, he felt, was Francie at her best.

“Could you work it?” he quavered, huskily.

“Work it?” Mrs. Hammond’s eyebrows rose the fraction of an inch. “I don’t understand you.”

“Well, I—er——” The rebuke to his coarse directness abashed Sir George. “What I mean is, Felicia’s an uncommonly attractive girl, and Roderick—well, Roderick——”

“Roddy is not at all unattractive, if you do not object to the rather weak type of young man. He inherits poor Lucy’s pretty eyes and hair. I can easily imagine any girl admiring him.”

At this statement Sir George’s mouth opened. He shut it again. The remark he had intended to make concerning the mental condition of a girl who could admire Roderick was suppressed at its source. In the circumstances he felt it would be injudicious.

“And, of course, he is a very good match. He will have your money some day, and the title. I should call him an excellent match. Then, again, I know Felicia is not in love with anybody else. And I have a great deal of influence with her.”

This last sentence removed Sir George’s lingering doubts.

If Francie undertook to put such a transaction through it was all over but cutting the wedding-cake.

“If you can persuade Roddy to propose,” said Mrs. Hammond, “I think I can answer for Felicia.”

“Persuade him! Roderick will do anything I tell him to. My goodness, Francie!” he exclaimed, “the thought of that boy safely married to a girl who has been trained by you is—well, I can’t tell you what I think of the idea. I only hope Felicia’s had the sense to pattern herself on you. Ah, there you are, Roderick.”

A timid knock had sounded on the door while he was speaking, and into the room there now came sidling a young man. He was a tall young man, thin and of an intellectual cast of countenance. The eyes and hair to which Mrs. Hammond had alluded, those legacies from “poor Lucy,” formed the best part of his make-up. The eyes were large and brown; the hair, which swept flowingly over his forehead, a deep chestnut.

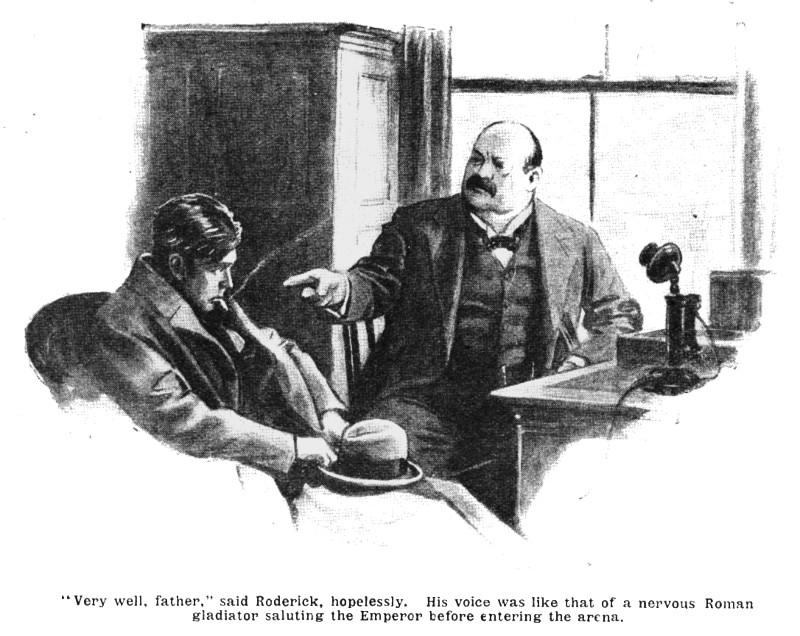

“How do you do, Aunt Frances?” said Roderick. His manner was nervous, and suggested that of men who visit dentists or of small boys who go by request into the studies of head masters. “Pilbeam says you want to see me, father.”

“I do,” said Sir George coldly. “Sit down.”

Mrs. Hammond rose with her customary tact.

“I think I will be running away,” she said. “I have some shopping to do.”

“I want to talk to you about Society Spice,” said Sir George severely. He retrieved the copy of the paper from the corner into which his just indignation had caused him to fling it, and began to turn its pages with knitted brow, Roderick eyeing him the while with all the care-free insouciance of a man watching a ticking bomb.

“Ha!” barked Sir George suddenly, lifting his son and heir a clear two inches off the seat of his chair. “Just as I thought! It isn’t there.”

“What, father?”

“The fourth instalment of that series on Bookmakers’ Swindling Methods. It has been discontinued. Why?”

“Well, you see, father——”

“Pilbeam told me it was a great success. He said there had been a number of letters about it.”

Roderick shuddered. He had seen some of those letters—the ones which Pilbeam, a jovial enthusiast, had described as the fruitiest of the bunch.

“Well, you see, father,” he bleated, “it was so frightfully personal.”

“Personal!” Sir George’s Jovian frown seemed to darken the room. “It was meant to be personal. Society Spice is a personal paper. Good heavens, you don’t suppose these bookmakers can afford to bring libel actions, do you?”

“But, father——”

“All the better if they did. It would be an excellent advertisement, and no jury would award them more than a farthing damages.”

Roderick shuffled unhappily.

“It isn’t so much libel actions.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, father, it’s like this. I happened to be down at Kempton Park last Saturday, and I met a man who told me that Ike Bullett was going about uttering the most awful threats.”

“Ike Bullett? Who’s Ike Bullett?”

“He’s one of the bookies. The articles have been particularly outspoken about him, you know. And he was threatening that if I didn’t stop them he would put the Lads on to me, and they would come and butter me over the pavement.”

Sensational as this announcement was, it seemed to leave Sir George completely unimpressed. Ike Bullett, he seemed to suggest, might put all the Lads in the world on to Roderick, but he couldn’t intimidate him, Sir George. He faced with a fine fearless unconcern the prospect of people buttering Roderick over the pavement.

“The series,” he said, “will be resumed. At once. Understand that?”

“Very well, father,” said Roderick hopelessly. His voice was like that of a nervous Roman gladiator saluting the emperor before entering the arena.

He turned to go, but the painful interview was not, it seemed, yet concluded.

“Wait,” said Sir George, “I have something else to say to you.”

Roderick poured himself into his chair once more.

MR. SINCLAIR HAMMOND, easy-going consort of the Egeria of the Mammoth Publishing Company, basked in the sunshine in the garden of Holly House, his residence on Wimbledon Common. There was a notebook on his knee, and he was scribbling industriously with a stubby pencil.

His tranquillity was largely due to the fact that he was alone. It had been quite an hour since anyone had bothered him. This was almost a record, and he had an uneasy feeling that it was too good to last. He was on the point of replacing his glasses and resuming his work when he saw that his forebodings had been well-grounded. A female figure had come out through the French windows of the drawing-room, and was making for him across the lawn.

Mr. Hammond sighed. Fond though he was of his wife, the Pyke blood in her made her occasionally a companion too restless and uncomfortable for a man who liked to sit and dream.

With a little moan he put on his glasses, and was relieved to see that it was not his wife who was approaching, but his niece, Felicia. This altered the situation entirely. He had no objection whatever to abandoning work in favour of a chat with Flick. They were firm friends and allies. Moreover, Flick shared his ability to see humour in the little things of life, a valuable gift in woman and one of the few great qualities which his admirable wife lacked.

He looked at her, as she drew near, with the same mild wonder which he always felt when he saw her nowadays. Seven years ago, when she had been dumped on him like a parcel on the death of his sister and her husband, Jack Sheridan, in a railway accident, she had been a leggy, scraggy, tousle-haired, freckled thing with nose and eyelids pink from much weeping, a curious object giving as little promise of beauty as a week-old baby. And now the sight of her suggested to him, given as he was to drawing his images from the Classics, a Hamadryad or some shepherdess strayed out of an Idyll of Theocritus.

“Hullo, Uncle Sinclair!” said Flick. She held out the overcoat she was carrying. “Get up!”

“I will not get up,” said Mr. Hammond. “Why should I get up? I refuse to get up for anyone.”

“Aunt Frances says it’s getting chilly, and she wants you to put on your light overcoat.”

Mr. Hammond put on the coat. He knew that the sleeves would brush against the paper when he resumed his writing, thus distracting his thoughts and leading to intemperate language, but the alternative, throwing the beastly thing into the goldfish pond, was impossible. If he continued to sit out here as he was and after a lapse of two months caught a cold, that cold would, he was aware, be put down to his reckless refusal to take the elementary precaution of wearing the light overcoat.

“You know, of course, that you are an abominable nuisance, child?” he observed, reseating himself.

“Of course,” said Flick equably. “It’s awfully nice of you to offer me your chair, but I shall be perfectly all right down here on the grass.”

“I wouldn’t give you this chair if you pleaded for it with salt tears,” said Mr. Hammond. “For one thing, you’re only going to stay a moment.”

“I’m not. I’ve come for a nice long talk.”

“Leave me, woman. Get back into your tree, you yellow-haired Hamadryad. Can’t you see I’m busy?”

Flick glanced up. She was looking, Mr. Hammond thought, unusually pensive.

“Are you really busy, uncle?”

“Of course not. I was just wondering when you came out how I should find a decent excuse for stopping work. Something on the mind, Flickie?”

Flick pulled at the grass thoughtfully.

“Uncle Sinclair, you know you always say you never give advice to anybody?”

“My guiding rule in life. I attribute my universal popularity to it.”

“I wish you would give me some.”

“Oh, you’re different. I’ll give you all you want. State your case.”

“Roderick has asked me to marry him. What do you think I ought to do?”

Mr. Hammond was appalled. Ironic, he reflected, to think that when he had found that it was Flick who was coming to disturb his privacy he had been relieved. But who would have supposed that she intended flinging frightful problems like this at his head?

“What does your aunt think?” he asked feebly, fighting for time.

“She thinks I ought to. But—I don’t know.”

A pang of pity for her innocence shot through Mr. Hammond. Francie had given her decision, and here the poor child was treating the matter as if it still lay open for debate.

“Your aunt knows best,” he said, and blushed hotly at the words. They sounded to him like something out of one of the novels of his boyhood.

“Yes, but this is something I’ve got to think out for myself, isn’t it?”

Mr. Hammond felt uneasy. He liked peace in the home, and this speech of Flick’s seemed to suggest that conditions might conceivably arise to render peace a memory of the past.

“Of course, I like Roddy,” said Flick meditatively.

“Splendid fellow,” agreed Mr. Hammond, heartily, growing more cheerful. He knew, as a fact, little or nothing of Roderick, for he was a man who avoided the society of his juniors: but if Francie endorsed him that settled it. “Good-looking chap, too.”

“Yes. In a way.”

“Ah,” said Mr. Hammond, bravely trying to keep it light, “I see what the trouble is. Constant association with me has set your standards a little too high. You must be practical, my child. There is only one Sinclair Hammond in the world. You will have to resign yourself to something short of perfection.”

Flick ran her fingers over the short grass.

“He isn’t very—exciting,” she said.

“You don’t want a jumpy husband, surely?”

“I don’t think I’ve got quite the right word. I meant—oh, well, this is what I mean, though it sounds horribly silly when one says it. I suppose every girl is sort of half in love with a kind of fairy prince. A sort of ideal, you know. Doesn’t it sound idiotic? Still, there it is, you know. And Roderick isn’t a fairy prince, is he?”

Her rain-washed eyes were more cloudy and serious than ever. The conversation seemed to be displaying a perilous tendency to plunge into the depths, and he disliked depths.

“I know exactly what you mean,” he said. “We all have one big romance in our lives which is apt to make everything else seem commonplace and dull—a beautiful, opalescent dream, very pleasant to dig up every now and then and brood over. Well, now, tell me your romance. From the way you were speaking, I’m sure you’ve had one. Out with it. Some fatal, fascinating boy with a jammy face and a Lord Fauntleroy suit whom you met at a birthday party, eh?”

Flick smiled indulgently.

“It isn’t quite so long ago as that.”

“Oh, then there really was somebody? Come on, child, confide in me. I’m quivering with excitement. Very bad for me, too, at my age.”

“You’ll laugh at me.”

“Not I.”

“I wonder,” she said, “if you remember taking me to stay with a Mr. Paradene when we were over in America? The time you did the lecture tour, you know. About five years ago, just before you married Aunt Francie.”

“Certainly. Do you suppose I’m as senile as all that? I can remember back much farther. Besides, Cooley Paradene is one of my best friends. We both collect old books, which gives us an excuse for writing to each other. Only man in the world I do write letters to. I’m always urging him to come here and pay me a visit. But how does he come into the story?”

“It was then that it happened.”

“What happened?”

“All the fairy-prince and beautiful-opalescent-dream stuff.”

Mr. Hammond regarded his niece with grave concern.

“Don’t tell me you are nurturing a secret passion for old Cooley? A little elderly for you, my child. Besides, you aren’t interested in old books. You wouldn’t appeal to him.”

“Don’t be silly. It was Bill.”

“What was Bill?”

“Bill West. Mr. Paradene’s nephew. He’s my great love, as you would call it.”

Mr. Hammond frowned thoughtfully.

“Bill? Bill? I must be getting senile after all. This William absolutely eludes my memory.”

“Oh, you must remember Bill. Mr. Paradene’s nephew at Harvard.”

“Bill? Bill?” Mr. Hammond’s face cleared. “Of course! A pimply youth with outstanding ears.”

“He wasn’t!” cried Flick, revolted.

“Ears,” insisted Mr. Hammond firmly, “which he used to hang his hat on when the rack in the hall was full.”

“Nothing of the kind. He was frightfully handsome and wonderful in every way.”

“Name one way in which he was wonderful,” said the sceptical Mr. Hammond.

“Well, I’ll tell you something wonderful that he did. He saved my life.”

“Saved your life?” Mr. Hammond was interested. “How did that happen?”

“We were bathing in Mr. Paradene’s lake, and I went out too far. As a matter of fact, we had finished bathing and I was supposed to be in my tent, dressing. But I couldn’t resist one last swim. It very nearly was my last, too. Bill had dressed, but he came out just in time and saw me struggling, and he dived in with all his clothes on——”

“Ass! Ought to have taken off his coat.”

“Well, perhaps he did take off his coat, and I wish you wouldn’t interrupt and spoil the story. He dived in and swam out to where I was kicking and screaming and brought me in safe and sound. I should have been done for in another half-minute. I had swallowed most of the lake.”

“And why is this the first I have heard of it?”

“We kept it dark. Bill, I suppose, was modest. At any rate, he begged me not to say anything about it, and I didn’t say anything because I jolly well knew I should be stopped bathing again if I did. He left next day to join some friends near Boston, and I’ve never seen him since.”

Her voice shook a little. Mr. Hammond lit his pipe thoughtfully. Though sympathetic, for he understood Flick, he decided to continue in the light vein.

“I shouldn’t worry about him, Flickie,” he said. “A fellow like that is sure to have been snapped up by now. Heroes don’t lie around loose for long. Concentrate on the sternly practical side of things, my dear. Fix your mind on Roderick. Here’s a young fellow whom you admit you like—good-looking, amiable, and the heir to a title and more money than you’ll be able to spend in half a dozen lifetimes, even if you start collecting old books. Upon my word, I think you could do worse.”

Flick was silent. She was wishing in a vague and formless way that life had not arranged itself quite like this: and yet she could not have said exactly what was her objection to the existing state of affairs. After all, she did like Roddy. And she had known him a long time. Not like being asked to marry a stranger.

And again—though everybody was very kind and pleasant and never so much as hinted it to her—there was no getting away from the fact that she was a penniless orphan, hardly in a position to take nebulous and fanciful objections to the quite attractive sons of millionaires.

“Yes, I think I’d better marry him,” she said.

CHAPTER II

the morning after

WILLIAM PARADENE WEST, after stirring uneasily on his pillow, opened his eyes; and, having blinked at the sunlight pouring in through the window, became aware that another day had begun and that the telephone at his bedside was ringing. At the same moment the door opened and Ridgway, his capable man-servant, entered.

“I think I heard the telephone, sir,” said Ridgway.

“So did I,” said Bill wanly.

The mists of sleep had rolled away, and returning consciousness was revealing the fact that he felt extremely unwell. His head had swollen unwholesomely to about twice its normal size and shooting pains shuddered through it. His mouth was full of some unpleasant flannel substance, which proved on investigation to be his tongue. Memory awoke. It all came back to him now. Last night Judson Coker had given a party.

Ridgway had removed the receiver.

“Are you there? Yes.” His voice was a well-modulated coo. The young master’s return home at a little after four in the morning had not passed unnoticed by Ridgway, and he knew instinctively that soft speech would be appreciated. “Yes, I will give Mr. West your message.” He turned to Bill and cooed anew like a cushat dove calling to its mate in spring. “Roberts, Mr. Cooley Paradene’s butler, on the telephone, sir. He requests me to inform you that Mr. Paradene returned from his travels yesterday and is very urgent that you should visit him this afternoon.”

Bill was in but poor shape for paying calls. However, Uncle Cooley’s invitations had the quality of royal commands. You cannot accept a large quarterly allowance from a man and decline to see him when desired.

“Down at Westbury?” he asked.

“At Westbury, sir, yes.”

“Tell him I’ll be there.”

“Very good, sir.” Ridgway relayed this information to the waiting Roberts and replaced the receiver. “Shall I prepare your breakfast, sir?”

Bill considered the point.

“I suppose so,” he said at length, without enthusiasm. Breakfast was never a popular meal with those who had enjoyed overnight the hospitality of Judson Coker. “Something pretty light.”

“Exactly, sir,” said Ridgway understandingly, and slid from the presence.

Bill lay on his back, staring at the ceiling.

He fell to meditation, and was still meditating when a voice spoke in his ear. It was a nasty rasping voice, not soft and gentle like Ridgway’s, and he recognised it immediately as that of Conscience. They had had arguments before.

“Well?” said Conscience, “up a bit late last night, eh?”

“A little.”

“I thought as much.”

“I was at a party at Judson Coker’s,” said Bill. “I had promised to go, so I had to. A man must keep his word.”

“A man need not lower himself to the level of the beasts of the field,” said Conscience coldly. “It begins to look to me as if you were something of a young waster.”

It was an offensive remark, but in his melancholy morning mood Bill found himself unable to combat it.

“I should think you’d have more self-respect and a rudimentary sense of decency,” proceeded Conscience. “You love Alice Coker, don’t you? Very well, then. A man who loves that noble girl ought to consider himself in the light of a priest or something. But do you? Not by a jugful. Lost to all sense of shame is the way I’d put it.”

This also struck Bill as true.

“I’ve had my eye on you, young man, for a long time, and I’ve about got you sized up. What’s the matter with you, among other things, is that you’re a worm, a loafer, a sponger, and a shiftless, backboneless disgrace to civilisation. You wasted your time at college. Yes, I am perfectly aware that you made the football team. I’m not saying you’re not a healthy and muscular young animal—what I’m complaining about is your soul. You’re simply not among those present when it comes to soul, and the soul is what brings home the bacon. As I was saying, you didn’t do a stroke of work at college, and ever since you’ve been hanging around, absolutely idle, living on your Uncle Cooley. It’s no good to say that he can give you this allowance of yours without feeling it. That’s not the point. I know perfectly well that he owns the Paradene Pulp and Paper Company and is a millionaire. What I am driving at is that you’re degrading yourself by sponging on him. You’re not a bit better than your Uncle Jasper.”

“Here, I say!” protested Bill. He had been prepared for a good deal, but this was overdoing it.

“Not one bit better than your Uncle Jasper and your Cousin Evelyn and all the rest of the family leeches,” insisted Conscience firmly. “Bloodsuckers, all of you. Uncle Cooley is the man with the money, and the entire family, you included, has been bleeding him for years.”

Bill’s spirit was broken.

“What shall I do about it?” he asked humbly.

“Do? Why, bustle about and earn a living for yourself. Get up, you wastrel, and show there’s something in you. Go to your uncle and tell him you want to work.”

Bill blinked at the ceiling. Conscience’s exordium had wrought powerfully upon him. That stuff about trying to be worthy of Alice Coker—that touched the spot. But what really stung was the suggestion that he was on a par with Uncle Jasper and Cousin Evelyn. That was a wicked punch. That most certainly wanted looking into. In all the world the persons he most despised were these relatives of his who loafed around living on Uncle Cooley.

The position of affairs in the Paradene family was one that is frequently met with in this world. Cooley Paradene, by means of a toilsome youth and a strenuous middle age, had amassed a large amount of money, and now all his poor relations had gathered round to help him spend it. His brother Otis had a business that required frequent subsidies: his brother-in-law, Jasper Daly, was an inventor whose only successful inventions were the varied methods he discovered of borrowing money: his niece Evelyn had married a man who was always starting new literary reviews. They were not people who agreed together on many subjects, but on this one point of electing Cooley to the post of family paymaster they had been unanimous.

For some years now Uncle Cooley had been showing in the matter of parting with money a pleasingly docile spirit for a man whose quickness of temper had at one time been a family byword. Something had happened to Mr. Paradene recently, purging the old Adam out of him; and his relatives were inclined to think that what had brought about the change was the hobby of collecting old books which had gripped him in his sixtieth year. He just mooned about his library at Westbury and signed cheques in that delightful absent-minded way we like to see in our rich relatives.

This was the man who had supported Bill West through college days and up to the moment when he lay in bed this morning, tortured by Conscience. Yes, Bill decided, Conscience had been right. Of course, he was not really as bad as Uncle Jasper and Cousin Evelyn, but he could see now that he had allowed himself to drift into an ambiguous position, and one that might easily lead people who did not know what a fine fellow he was to form mistaken judgments. Most assuredly he must go to Uncle Cooley and announce his readiness to accept a job of work.

Filled with resolution, Bill heaved himself up with a groan and made for the bathroom.

There is magic in a cold shower. In combination with Youth few ills of the flesh can stand against it. Drying his glowing body five minutes later, Bill, though still tender about the head and apt to leap at sudden noises, felt on the whole a new man.

It was about time that Uncle Cooley had a real live-wire looking after the Pulp and Paper Company’s affairs. The old boy had been a hustler in his day, but for the past few years he had allowed a taste for travel and the fascination of his library to take up too much of his time. What the Paradene Pulp and Paper Company wanted was new blood, and he, Bill, was the man to supply it.

He dressed and went in to his light breakfast. So exalted was he by now that his dreams of the future began definitely to include a lifelong union with Alice Coker.

“Mr. Judson Coker on the telephone, sir,” said Ridgway, oozing softly in like some soundless liquid.

Bill walked to the telephone in a cold, hard, censorious mood. It was impossible for him in his reformed condition to think of his friend and host of last night without a puritanical shudder.

“Hullo?” said Bill. He spoke crisply and in a manner to discourage badinage. Not that Judson, after last night’s celebrations, was likely to indulge in airy quips.

A voice sounded over the wire.

“That you, Bill, o’ man?”

“Yes.”

“So you got home all right?” said the Voice in tones of surprised congratulation.

Bill resented this reminder of a past now discarded forever.

“Yes,” he said, frigidly. “What do you want?”

“Just remembered, Bill, o’ man. Most important thing. I invited half a dozen of the Follies girls to come on a picnic this afternoon.”

“Well? What about it?”

“I’m relying on you to rally round.”

Bill frowned—such a frown as St. Anthony might have permitted himself.

“You are, are you?” he said sternly. “Then listen to me, you poor fish! Let me tell you that I’m a changed man and wouldn’t be seen dead in a ditch with a Follies girl. And if you’ll take my advice, you’ll pull up and try to realise that life is stern and earnest and meant for something better than——”

An awed gasp interrupted his harangue.

“Gosh, Bill,” quavered the Voice, “I noticed you buzzing around pretty energetically last night, but I’d no notion you would be quite so bad this morning. You must have got the head of a lifetime. Absolutely of a lifetime!” The Voice sank to an earnest whisper. “What you want to do, Bill, o’ man, is to take a couple of Never-Say-Dies. That’s what I’m going to do. You remember the recipe? One raw egg in half a wineglassful of Worcester Sauce, sprinkle liberally with red pepper, add four aspirins, and stir. Put you right in no time!”

And this man was Her brother! Bill shuddered.

“I am feeling perfectly well, thank you,” he said austerely.

“Fine! Then you will come to the picnic after all?”

“I will not. I wouldn’t have dreamed of doing so in any case, but, as it happens, I have a previous engagement. I’ve got to go to my uncle’s place at Westbury. He got home yesterday, and ’phoned me this morning.”

“My dear chap! Say no more!” The Voice was cordial and sympathetic. “I quite understand. You mean the uncle who unbelts the allowance on the first of every quarter? Of course you must go and see him. I suppose you’ll grab the chance of touching him for a bit extra?”

“If you want to know just what I’m going to do when I see Uncle Cooley,” said Bill coldly, “I’ll tell you. I’m going to ask him for a job.”

There was an exclamation of annoyance at the other end of the wire.

“This darned ’phone is out of order,” complained the Voice. “You can’t hear a thing. It sounded just as if you said something about asking your uncle for a job.”

“That is exactly what I did say.”

“Do you mean work?”

“Work.”

The Voice became almost tearful in its agitation.

“Don’t do it, Bill! Don’t do it, o’ man. You aren’t yourself. It’s just having this head that’s giving you ideas like that. Do take the advice of an old pal and mix up a Never-Say-Die. It never fails. Guaranteed to make a week-old corpse spring from its bier and enter for the Six-Day Bicycle-Race.”

Bill hung up the receiver, revolted. He was returning to his breakfast when the telephone bell rang again. Indignant at this pertinacity on the part of his despicable friend, he strode back and spoke with wrathful brusqueness.

“Well! What do you want now?”

“Oh, Mr. West, is that you?”

It was not Judson at all. The voice was a female one; and, hearing it, Bill tottered with indescribable emotion. It was She! And he—criminal fool, misguided blackguard that he was—had spoken angrily! Ye gods! That even in error he should have addressed her so. That “Well!” That emphasis on the “now.” It was vile, brutal, fiendish. Words poured from him in an apologetic flood.

“Miss Coker, I’m terribly sorry—I don’t know how to apologise—I thought it was somebody else—I didn’t mean—I wouldn’t have—I hope you aren’t—I hope I haven’t——”

“Mr. West,” said his audience, taking advantage of a lull, “I wonder if you would do me a great favour?”

Bill’s knees gave at the joints. He swayed deliriously.

“Do you a favour?” he breathed, fervently. “You bet I will!”

“It’s very important. Can you come and see me this morning?”

“You bet I can!”

“Thank you so much.”

He returned to the sitting-room and, going to the mantelpiece, inspected very carefully and reverently all the photographs of Miss Coker which it contained—eleven in all, painfully and laboriously acquired by the slow process of sneaking them one by one out of Judson’s rooms.

If Bill had not been so immersed in thoughts of Alice, he might have observed a scared expression in the eyes of the maid who admitted him to the residence of Mr. J. Birdsey Coker shortly after half past twelve. But, being so immersed, it was not until he reached the drawing-room and found himself looking into the lovelier eyes of the mistress of the house that he suspected any calamity.

“Good heavens!” he exclaimed. “What’s the matter?”

Alice Coker was an amazingly handsome girl. She was modelled on rather queenly lines, unlike her brother Judson, who looked like an Airedale terrier. Her features were perfect, her teeth were perfect, her hair was perfect.

“Sit down, Mr. West,” she said, formal even in her agitation.

Bill sat down, registering devotion, sympathy, and willingness to do all that a red-blooded man may for Beauty in distress.

“It was very good of you to come,” said Alice.

“No, no. Oh, no. No, no. No, no,” said Bill.

“It’s about Judson.”

“Judson?”

“Yes. Father is simply furious. Not,” proceeded the fair-minded Miss Coker, “that you can really blame him. Juddy did behave very badly.”

Bill found himself in something of a dilemma. He wished to agree with every word she spoke, but horrified condemnation of Judson at this point might, he felt, be resented. Besides, he was handicapped in the capacity of censor of morals by not knowing what his convivial friend had been doing to excite the parental wrath to such an extent. He contented himself with making a low, honking noise like a respectful wild-duck.

“Apparently Judson gave a party last night,” said Miss Coker. She sniffed disdainfully. “A very rowdy party to a lot of impossible girls from the theatres. What pleasure he gets from mixing with such people,” she went on severely, “I cannot see.”

“No,” said Bill virtuously. “No. You’re quite right. No.”

“The trouble with Juddy is that he is weak and his friends lead him astray.”

“Exactly,” said Bill, trying to look like one of the friends who didn’t.

“Well, what happened was this,” resumed Miss Coker. “We all went to bed at the usual time, and were sound asleep, when—about four in the morning—there was a violent knocking on the front door. Poor father went down in his slippers and dressing-gown—rather cross—and there was Judson.”

She paused, and a look of pain came into her fine eyes.

“Judson,” she went on in a toneless voice, “seemed glad to see father. When I looked over the banisters, he was patting him on the back. Father asked him what he wanted, and Judson said that he had lost his Lucky Pig and thought he might have left it on the piano in the drawing-room the last time he was in the house. He came in and hunted about and then returned to his flat. About half an hour later he was on the doorstep again, banging the knocker, and when father got out of bed and went down, Judson said he had only come to apologise for disturbing us. He said he wouldn’t have done it, but he had particularly wanted to show the pig to a girl who was at the party. He came in and had another search, then he went away again. And at half-past five he called up on the telephone—it’s in father’s room—and begged father to have a look round and see if the pig wasn’t in the study.”

She paused again. Bill made shocked noises.

“Naturally, father was very much annoyed. You ought to have seen him when he left for the office this morning.”

Bill, as he listened to his adored one’s word-picture of the passing of her parent from the bosom of his family, was glad he had not seen him.

“And the result is,” concluded Alice, “that he says he has had enough. He says he is going to stop Judson’s allowance and send him to grandmamma’s farm in Vermont, and keep him there till he gets some sense. And what I wanted to ask you, Mr. West, is this. Could you fit it in with your plans to take Juddy away on a month’s fishing-trip?”

“But you said he was going to Vermont.”

“Yes. But I believe that when father has had time to cool down a little he will agree to letting him go on a fishing-trip instead, provided it is with someone who will look after him and see that he gets nothing to drink. It doesn’t so much matter where he goes, you see, so long as he gets away from New York and all these people who cluster round him and lead him astray. Juddy,” said Miss Coker, a break in her voice, “is such a dear boy that everybody is attracted to him, and that makes it difficult for him to be strong and resist temptation.”

Bill hesitated no longer. He had been doubtful for a time as to Judson’s exact standing with his sister; but now that it became manifest that not all the dark deeds which the reprobate had performed on the front doorstep in the small hours could shake her divine affection he saw his way clear. He embarked forthwith on an eulogy of his late playmate, the eloquence of which surprised even himself.But its effect on Miss Coker was remarkable. Her proud aloofness thawed. She melted visibly, and beamed upon him like the rising sun.

“I knew you were a great friend of his,” she said with such cordiality that Bill twisted his legs round each other and gasped for air. “That’s why I asked you to come here. You don’t know what it would be like for the poor boy at grandmamma’s. He would have to get up at seven every morning, and there would be family prayers twice a day.”

In solemn silence they peered into this Inferno from which she had removed the lid.

“Prayers?” faltered Bill.

“And hymns on Sundays,” said Miss Coker, tight-lipped. “It would drive the poor darling off his head. And as far as his health is concerned, a fishing-trip would do him just as much good. I don’t know how to thank you, Mr. West. But I knew you would not fail me. I am tremendously grateful.”

There is a tide in the affairs of men which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune. It seemed to Bill that the moment of his own flood-tide had arrived. At no time in the past year had so favourable an opportunity for proposing presented itself, and it might be many a long month before such a chance occurred again.

“Miss Coker, I—that is to say—or putting it another way—I wonder—do you think——”

He paused. He was not sure if he was making his meaning quite clear. He tried again.

“I know—it isn’t as if—I quite see—it might happen—if you would——”

He swallowed twice and approached the subject from a new angle.

“Look here,” he said, “will you marry me?”

Miss Coker exhibited an unruffled composure. It is to be assumed that this sort of thing had happened to her before.

“Really,” she said, “I wasn’t expecting this.”

Nor was Bill. He was still stupefied by the sound of those reckless words and wondered dazedly how he could ever have had the nerve to allow them to pass his lips.

“I can’t give you a definite answer now.”

“No, no, of course not.”

“Suppose you ask me again when you have brought Juddy back quite well and strong?”

The assumption that Judson was an invalid in the last stages of egg-shell fragility did not quite square with Bill’s recollection of his friend leading the revels on the previous night, but he let it go. It was unimportant. The thing that really mattered was that she had not scornfully rejected his suit and rung the bell for menials to come and throw him into the street.

“We’ll leave it like that, shall we?”

“Yes,” said Bill, humbly.

“And when do you think you will be able to start on this fishing-trip?” asked Miss Coker, who inherited from her father the gift of being able to shelve sentiment in favour of business. “At once?”

“To-morrow, if you like,” said the infatuated Bill.

He perceived dimly that this new arrangement was going to make it difficult for him to jump right in and assume control of his uncle’s pulp-paper business, but that seemed of slight importance now. He basked for a moment in the warmth of the smile which she bestowed upon him, and was reminded by that smile of a request he wished to make.

“I wonder,” he stammered, “I mean—would you—do you think—what I want to say is, you haven’t by any chance a photograph of yourself you could give a fellow?”

“Why, of course,” said Alice, amiably.

“I’ve been wanting one of you for a long time,” said Bill.

CHAPTER III

the family

THE library of Mr. Cooley Paradene at his house at Westbury, Long Island, was a room which caused bibliophiles on entering it to run round in ecstatic circles.

Bill, not being a bibliophile, bore the spectacle with more calm. On being shown into the library by Roberts, who informed him on his arrival at three o’clock that afternoon that Mr. Paradene would be disengaged shortly and desired him to wait, he made immediately for the curtained bow-window, from which there was a view almost ideally arranged for the contemplation of one in his emotional state. Beneath the window hung masses of laburnum, through which the observer might note and drink in the beauty of noble trees, a silver lake, and a broad expanse of shady lawn. Just what a man in love wanted, felt Bill.

There was but one flaw. The broad expanse of shady lawn was, he disgustedly perceived, marred at the moment by the presence of humanity, for which in his exalted condition he was in no mood. He resented the intrusion of an old man with a white beard and a small boy in knickerbockers. However, at this moment they started to move towards the house, and presently the laburnum hid them and he was at peace again. He gave himself up once more to thoughts of Alice.

True, she had not actually committed herself to an engagement, but what of that? She had as good as said that, like some knight of old, he had merely to perform his allotted task and she would be his.

His meditations were interrupted by the opening of the door.

“Mr. Jasper Daly,” said the voice of Roberts.

From his post behind the curtains Bill heard a testy snort.

“What’s the sense of announcing me, my good man? There’s nobody here.”

“Mr. West was here a moment ago, sir.”

“Eh? What’s he doing here?”

Bill came out from his nook.

“Hullo, Uncle Jasper,” he said, and strove in vain to make his voice cordial. After what had passed between Conscience and himself that morning the spectacle of Mr. Daly was an affliction.

“Oh, there you are,” said Uncle Jasper, grumpily, looking round with a pale reptilian eye.

“Mr. Paradene is engaged for the moment, sir,” said Roberts. “He will be with you shortly. Shall I bring you a cocktail, sir?”

“No,” said Uncle Jasper. “Never drink ’em.” He turned to Bill. “What you doing here?”

“Roberts called up this morning to say that Uncle Cooley wanted to see me.”

“Eh? That’s queer. I had a telegram yesterday myself saying the same thing.”

“Yes?” said Bill distantly.

A moment later he had a fresh burden to bear.

“Mrs. Paradene-Kirby,” proclaimed Roberts in the doorway.

The arrival of his Cousin Evelyn deepened Bill’s gloom. Even at the best of times she was hard to bear. A stout and voluminous woman in the early forties, with eyes like blue poached eggs, she had never had the sense to discard the baby-talk which had so entertained the young men in her débutante days.

“Ooh, what a lot of g’ate big booful books!” said Cousin Evelyn, addressing, apparently, the small fluffy dog which she bore in her arms. “Ickle Willie-dog must be a good boy and not bite the books and maybe Uncle Cooley will give him a lovely cakie.”

“Mr. Otis Paradene and Master Cooley Paradene,” announced Roberts.

Bill now felt drearily resigned. To a man compelled to be in the same room with Uncle Jasper and Cousin Evelyn, the additional discomfort of Otis and little Cooley was negligible.

“Good God!” cried Uncle Jasper, staring at the new arrivals. “Is this Old Home Week? What you all doing here?”

“Cooley and I were specially telegraphed for,” replied Otis with dignity.

“Why, how puffickly ’straordinary!” said Cousin Evelyn. “So was I.”

“And he,” said Uncle Jasper, plainly bewildered, jerking a thumb at Bill, “had a ’phone-call this morning. What’s the idea, I wonder?”

Then the family went into debate on the problem.

Bill could endure no more. Admitting that he was a bloodsucker—and Conscience had made this fact uncomfortably clear—he had at any rate always been grateful for blood received.

“You people make me sick,” he snapped, wheeling round. “You ought to be put in a lethal chamber or something. Always plotting and scheming after poor old Uncle Cooley’s money——”

This unexpected assault from the rear created a certain consternation.

“The idea!” cried Cousin Evelyn.

“Impudent boy!” snarled Uncle Jasper.

Uncle Otis tapped the satirical vein.

“You’ve never had a penny from him, have you? Oh dear, no!” said Uncle Otis.

Bill shot a proud and withering glance in his direction.

“You know perfectly well that he gives me an allowance. And I’m ashamed now that I ever let him do it. When I see you gathering round him like a lot of vultures——”

“Vultures!” Cousin Evelyn drew herself up haughtily. “I have never been so insulted in my life.”

“I withdraw the expression,” said Bill.

“Oh, well,” said Cousin Evelyn, mollified.

“I should have said leeches.”

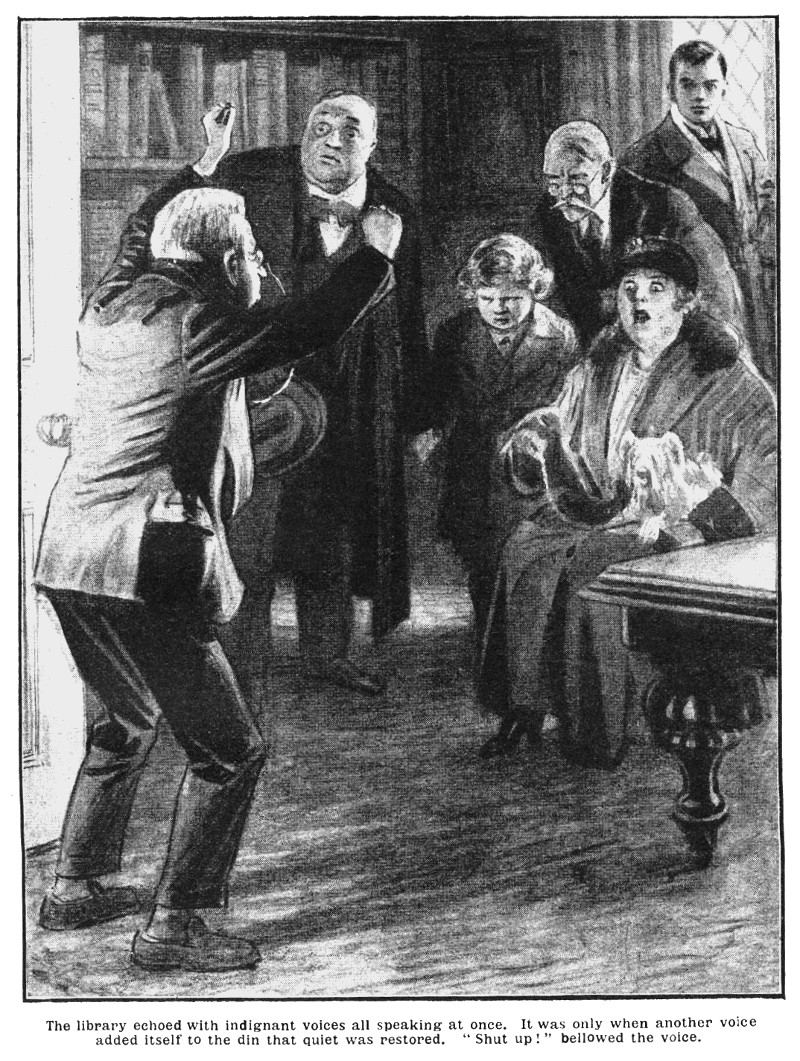

The Paradenes were never a really united family, but they united now in their attack upon this critic. The library echoed with indignant voices, all speaking at once. It was only when another voice added itself to the din that quiet was restored.

“Shut up!” bellowed this voice.

It was a voice out of all proportion to the size of its owner. The man standing in the doorway was small and slight. He had a red, clean-shaven face, a noble crop of stiff, white hair, and he glared at the gathering through rimless pince-nez.

“A typical scene of Paradene family-life!” he observed sardonically.

His appearance was the signal for another united movement on the part of the uncles and cousins.

“ ’Lo, Cooley. Glad to see you.” (Uncle Jasper.)

“Welcome home, Cooley.” (Uncle Otis.)

“You dear man, how well you look!” (Cousin Evelyn.)

Silence. (Little Cooley.)

More silence. (Bill.)

The little man in the doorway seemed unappreciative of this deluge of affection. Now that he was no longer speaking his mouth had set itself in a grim line, and the gaze he directed at the effusive throng through his rimless glasses might have damped more observant persons.

Then Uncle Jasper took the floor.

“Could you give me five minutes in private later on, Cooley?” he said. “I’ve a little matter to discuss.”

“I, too,” said Otis, “have a small favour to ask on little Cooley’s behalf.”

Cousin Evelyn thrust herself forward.

“Give g’ate big uncle Cooley a nice kiss, darling,” she cried, extending the fluffy dog with two plump arms in the general direction of the benefactor’s face.

Mr. Paradene’s reserve was not proof against this assault.

“Take him away!” he cried, backing hastily. “So,” he said, “you aren’t satisfied with sponging on me for yourselves—started hunting me with dogs, eh?”

Cousin Evelyn’s face expressed astonishment and pain.

“Sponging, Uncle Cooley!”

“Yes, sponging! I don’t know if you’ve taught that damned dog of yours any tricks, Evelyn, but if he can sit up on his hind legs and beg he’s qualified for full and honourable standing in this family. That’s all any of you know how to do. I get back here after two months’ travelling, and the first thing you all do is hound me for money.”

Sensation. Uncle Jasper scowled. Uncle Otis blinked. Cousin Evelyn drew herself up with the same hauteur which she had employed a short time before upon Bill.

“I am sure,” she said, hurt, “horrid money is the last thing I ever think of.”

Mr. Paradene uttered an unpleasant laugh. Plainly he had come back from his travels in no mood of goodwill to all.

“Yes,” he said bitterly, “the last thing at night and the first thing in the morning. I tell you I’m sick of you all. Sick and tired. You’re just a lot of—of——”

“Vultures,” prompted Bill helpfully.

“Vultures,” said Mr. Paradene. “All so friendly and all so broke. For years and years you’ve done nothing but hang on to me like a crowd of——”

“Leeches,” murmured Bill. “Leeches.”

“Leeches,” said Mr. Paradene. “Ever since I can remember I have been handing out money to you—money, money, money. And you’ve absorbed it like so many——”

“Pieces of blotting-paper,” said Bill.

Mr. Paradene glared at him.

“Shut up!” he thundered.

“All right, uncle. Only trying to help.”

“And now,” resumed Mr. Paradene, having disposed of Bill, “I want to tell you I’ve had enough of it. I’m through. Finished. I called you together to-day to make an announcement. I have a little surprise for you all. You are about to acquire a new relative.”

The family looked at each other with a wild surmise.

“Don’t tell me,” whispered Uncle Jasper in a bedside voice, “that you are going to get married.”

“No,” said Mr. Paradene, “I am not. The relative I refer to is my adopted son. Horace! Come here, Horace.”

Through the doorway there shuffled a small, knickerbockered figure.

“Horace,” said Mr. Paradene, “let me present you to the family!”

The boy stared for a moment in silence. He was a sturdy, square-faced, freckled boy with short sandy hair and sardonic eyes. His gaze wandered from Uncle Jasper to Uncle Otis, from little Cooley to Cousin Evelyn, drinking them in.

“Is this the family?” he asked.

“This is the family.”

“Gee whistikers, what a bunch of prunes!” said the boy, with deep feeling.

IN the silence which followed this frank statement of opinion, another figure added itself to the group. This was a large and benevolent-looking man in a frock-coat, whom Bill recognised by his white beard as the boy Horace’s companion on the lawn. He was smiling a grandfatherly smile—the only smile of any description, it may be mentioned, on view in the room at that particular time.

Horace was the first to speak, and his words revealed what was weighing upon his mind.

“Do I have to kiss them all?” he asked, apprehensively.

“You are certainly not going to kiss me,” said Uncle Jasper definitely, waking from his stupor. He rounded on Mr. Paradene, puffing like a seal. “What is the meaning of this, Cooley?” he demanded.

Mr. Paradene waved a hand in the direction of the newcomer.

“Professor Appleby will explain.”

The minor prophet bowed. If he felt any embarrassment he did not show it.

“The announcement which my good friend Paradene——”

“How do you mean, your good friend Paradene?” inquired Uncle Jasper heatedly. “How long have you known him, I should like to know.”

“I met Professor Appleby on the train coming from San Francisco,” said Mr. Paradene. “It was he——”

“It was I,” said Professor Appleby, breaking gently in, “who persuaded Mr. Paradene to adopt this little lad here.” He patted the boy’s head and regarded his fermenting audience kindly. “My name,” he proceeded, “is possibly not familiar to you, but in certain circles, I think I may assert with all modesty, my views on eugenics are considered worthy of attention. Mr. Paradene, I am glad to say, has allowed himself to be enrolled among my disciples. I am a strong supporter of Mr. Bernard Shaw’s views on the necessity of starting a new race, building it with the most perfect specimens of the old. Horace here is a boy of splendid physique, great intelligence, sterling character and wonderful disposition. I hold—and I am glad to say that he agrees with me—that it is better for Mr. Paradene to devote his money to the rearing and training of such a boy than to spend it on relatives who—may I say—have little future and from whom he can expect—pardon me—but small returns.”

The relatives gave tongue. All through this harangue they had been trying to speak, but Professor Appleby was not an easy man to interrupt. Now that he had paused, they broke out.

“I never heard of such a thing in my life!”

“The fellow’s a dangerous crank!”

“Is it really possible that you intend to make this—this uncouth boy your heir rather than your own flesh and blood?”

Professor Appleby intervened gently.

“One must admit,” he acknowledged, “that Horace is at present a trifle unpolished. I quite see that. But what of it? A good tutor will remedy so small a defect in a few months. The main thing is that the little lad is superbly healthy and extremely intelligent.”

The little lad made no acknowledgement of these stately tributes. He was still wrestling with the matter nearest his heart.

“I will not kiss ’em,” he now announced firmly. “No, sir! Not unless somebody makes me a bet about it. I once kissed a goat on a bet.”

Cousin Evelyn threw up her hands, causing Willie-dog to fall squashily to the floor.

“What an impossible little creature!”

“I think, my dear Paradene,” said Professor Appleby mildly, “that, as the conversation seems to be becoming a little acrimonious, it would be best if I took Horace for a stroll in the grounds. It is not good for his growing mind to have to listen to these wranglings.”

Cousin Evelyn stiffened militantly.

“Pray do not let us disturb Horace in his home.” She attached a lead to Willie-dog’s collar and made for the door. “Good-bye, Uncle Cooley,” she said, turning. “I consider I have been grossly and heartlessly insulted.”

With one long, silent look of repulsion Cousin Evelyn gathered Willie-dog into her arms and passed out. Uncle Jasper stumped to the door.

“Good-bye, Jasper,” said Mr. Paradene.

“Good-bye. I shall immediately take steps to have a lunacy commission appointed to prevent you carrying out this mad scheme.”

“And I,” said Uncle Otis, “I have only to say, Cooley, that the journey here has left me out of pocket to the extent of three dollars and seventy-nine cents. You shall hear from my lawyer.” He took little Cooley by the hand. “Come, John,” he said bitterly. “In future you will be known by your middle name.”

Horace observed this exodus with a sardonic eye.

“Say, I seem to be about as popular as a cold welsh rabbit!” he remarked.

Bill came forward amiably.

“I’ve got nothing against you,” he said. “As far as I’m concerned, welcome to the family!”

“If that’s the family,” said Horace, “you’re welcome to ’em yourself.”

And, placing his little hand in Professor Appleby’s, he left the room. Mr. Paradene eyed Bill grimly.

“Well, William?”

“Well, Uncle Cooley?”

“I take it that you have gathered the fact that I do not intend to continue your allowance?”

“Yes, I gathered that.”

His young relative’s calm seemed to embarrass Mr. Paradene a little. He spoke almost defensively.

“Worst thing in the world for a boy your age to have all the money he wants without earning it.”

“Exactly what I feel,” said Bill, enthusiastically. “What I need is work. It’s disgraceful,” he said warmly, “that a fellow of my ability and intelligence should not be making a living for himself. Disgraceful!”

Mr. Paradene’s sanguine countenance took on a deeper red.

“Very humorous!” he growled. “Very humorous and whimsical. But what you expect to gain by——”

“Humorous! You don’t imagine I was being funny, do you?”

“I thought you were trying to be.”

“Good lord, no! Why, I came here this afternoon fully resolved to ask you for work.”

“You’ve taken your time getting round to it.”

“I didn’t get a chance to mention it before.”

“And what sort of work do you suppose I can give you?”

“A job in the firm.”

“What as?”

Bill’s extremely slight knowledge of the ramifications of the pulp-and-paper business made this a difficult question to answer.

“Oh, anything,” he replied, with valiant spaciousness.

“I could employ you at addressing envelopes at ten dollars a week.”

“Fine!” said Bill. “When do I start?”

Mr. Paradene peered at him suspiciously through his glasses.

“Well, I’m bound to say,” observed Mr. Paradene, after a pause, seeming a trifle disconcerted, “your attitude has taken me a good deal by surprise. It’s an odd thing, William, but the only member of my family for whom I still retain some faint glimmer of affection is you.”

Bill smiled his gratification.

“And you,” boomed Mr. Paradene, “are an idle, worthless, good-for-nothing. Still, I’ll think it over. You’re not going back to the city at once?”

“Not if you want me.”

“I may want you. Stay here for another hour or so.”

“I’ll go and stroll by the lake.”

Mr. Paradene scrutinized him keenly.

“I can’t understand it,” he muttered. “Wanting to work! I don’t know what’s come over you. I believe you’re in love or something.”

CHAPTER IV

the boy horace

FOR about a quarter of an hour after the parting of uncle and nephew perfect peace brooded upon Mr. Cooley Paradene’s house and grounds. At the end of that period Roberts, the butler, agreeably relaxed in his pantry over a cigar and a tale of desert love, was startled out of his tranquillity by the sound of a loud metallic crash, appearing to proceed from the drive immediately in front of the house. Laying down cigar and book, he bounded out to investigate.

It was not remarkable that there had been a certain amount of noise. Hard by one of the Colonial pillars which the architect had tacked on to Mr. Paradene’s residence to make it more interesting, lay the wreckage of a red two-seater car, and from the ruins of this there was now extricating itself a long figure in a dust-coat, revealed a moment later as a young man of homely appearance with a prominent, arched nose and plaintive green eyes.

“Hullo,” said this young man, spitting out gravel. “How’s everybody?”

Roberts gazed at him in speechless astonishment. The wreck of the two-seater was such a very comprehensive wreck that it seemed hardly possible that any recent occupant of it could still be in one piece.

“Had a bit of a smash,” said the young man.

“An accident, sir?” gasped Roberts.

“If you think I did it on purpose,” said the young man, “prove it!” He surveyed the ruins interestedly. “That car,” he said sagely, after a prolonged scrutiny, “will want a bit of attention.”

“However did it happen, sir?”

“Just one of those things that do happen. Coming up the drive at a pretty good lick when a bird settled in the middle of the fairway. Tried to avoid running over the beastly creature, and must have pulled the wheel too far round. Because all of a sudden I skidded a couple of yards, burst a tyre, and hit the side of the house.”

“Good heavens, sir!”

“It’s all right,” said the young man, reassuringly; “I was coming here, anyway.”

He discovered a deposit of gravel on his left eyebrow and removed it with a blue silk handkerchief.

“This is Mr. Paradene’s house, isn’t it?” he asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Good. Is Mr. West here?”

“Yes, sir.”

“That’s fine. I wish you would tell him I want to see him. Coker’s the name, Mr. Judson Coker.”

“Very good, sir.”

Something in the butler’s manner, a certain placidity and lack of emotion, appeared to displease the young man. He frowned slightly.

“Judson Coker,” he repeated.

“Yes, sir.”

Judson looked at him expectantly.

“Name’s familiar, eh?”

“No, sir.”

“You mean to say you’ve never heard it before?”

“Not to my knowledge, sir.”

“Good God!” said Judson.

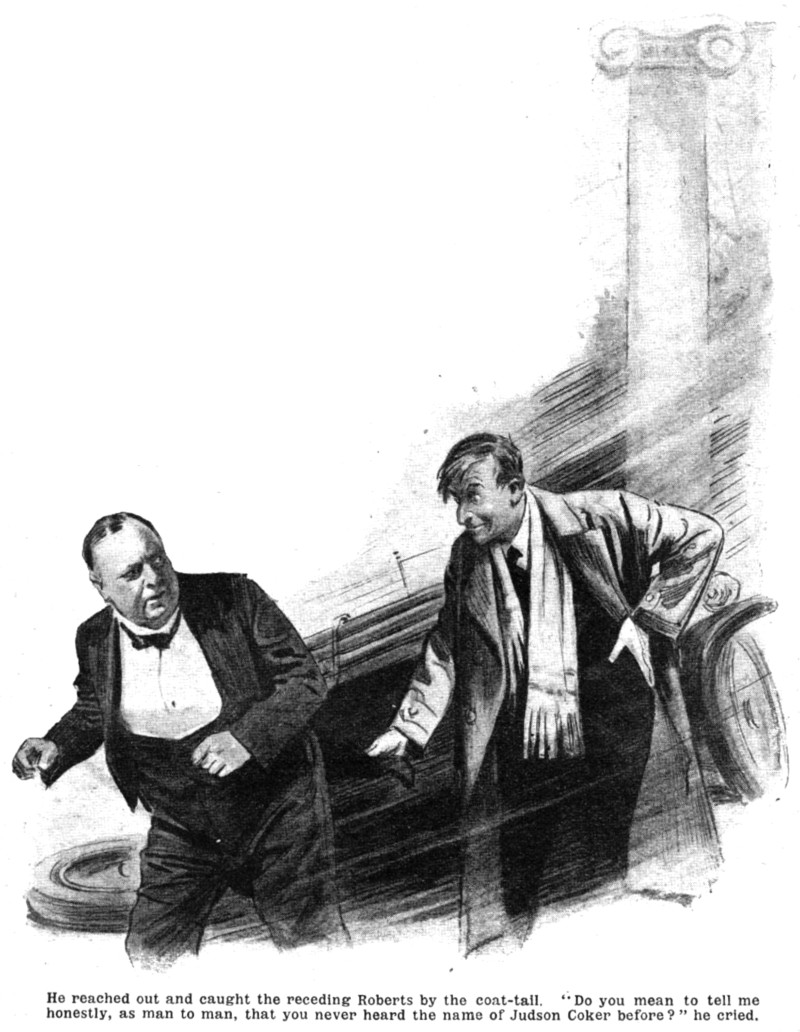

He reached out a long arm and detained the receding Roberts by the simple process of seizing the tail of his coat. Even in his moods of normalcy there was never anything aloof and reticent about Judson Coker; he was always ready to chat anywhere at any time with anyone; and now his accident had brought about in him a still greater urge towards loquacity. Shocks affect different people in different ways. Judson’s had left him bubblingly confidential.

“Do you mean to tell me honestly as man to man,” he demanded incredulously, “that you have never heard the name Judson Coker before?”

“No, sir.”

“Good God!”

He released the butler’s coat-tail and relapsed into a moody silence.

“Shall I bring you a whisky-and-soda, sir?” asked Roberts. It had come home to him by this time that the young visitor was not wholly himself, and remorse swept over him.

The question restored Judson’s cheerfulness immediately. It was the sort of question that never failed to touch a chord in him.

“My dear old chap, you certainly may,” he responded with enthusiasm. “I’ve been wondering when you were going to lead the conversation round to serious subjects. Mix it pretty strong, will you? Not too much water and about the amount of whisky that would make a rabbit bite a bull-dog.”

The butler retired, to return a few moments later with the healing fluid. He found his young friend staring pensively at the sky.

“I say,” said Judson, breathing a satisfied sigh as he lowered his half-empty glass, “coming back to that, you were kidding just now, weren’t you, when you said you didn’t know my name?”

“No, sir, I assure you.”

“Well, this is the most extraordinary thing I ever heard. You seem to know about as much of what’s going on in the world as a hen does of tooth-powder.”

“We live very much out of the great world down here, sir.”

“I suppose you do,” said Judson, cheered by this solution. “Yes, I guess that must be it. Quite likely you might not have heard of me if that’s so. But you can take it from me that I’ve done a lot of things in my time. Clever things, you know, that made people talk. If it hadn’t been for me I don’t suppose the custom of wearing the handkerchief up the sleeve would ever have been known in America.”

“Indeed, sir?”

To some men these reminiscences might have proved enthralling, but not to one who, like Roberts, was in the middle of chapter eleven of “Sand and Passion” and wanted to get back to it. He removed the decanter gently from the reach of Judson’s clutching hand and tactfully endeavoured to end the conversation.

“I made inquiries, sir, and was informed that Mr. West was last seen walking in the direction of the lake. Perhaps if you would care to look for him there——? Ah, but here is Mr. West, coming up the drive.”

IT was the unwelcome arrival on its grassy shores of Professor Appleby and the boy Horace that had driven Bill from the lake. He was in no mood for conversation, for it had suddenly become plain to him that he had got to do some very tense thinking. Events since his coming to Mr. Paradene’s house had marched so rapidly that he had not had leisure until this moment to appreciate the problems and complexities with which life had filled itself.

Brooding now upon these, he could see that Fate had manœuvred him into a position where he was faced with the disagreeable necessity of being in two places at one and the same time. Obviously, if his newly-displayed enthusiasm for toil was to carry weight, he must enter Uncle Cooley’s office immediately. Obviously, also, if he entered Uncle Cooley’s office immediately, he could not take Judson off for a fishing-trip. If he went off now upon a fishing-trip, what would Uncle Cooley think of him? And conversely, if he cancelled the fishing-trip, what would Alice Coker feel but that he had failed her in her hour of need after buoying her up with airy promises? Bill staggered beneath the burden of the problem, and was so preoccupied that Judson had to call him twice before he heard him.

“Why, hullo, Judson! What on earth are you doing here?”

He wrung his hands with considerable animation. Since their somewhat distant talk on the telephone that morning his mental attitude towards Judson had changed a good deal. In his capacity of practically-accepted suitor of sister Alice, Bill had taken on a sort of large benevolence towards her entire family.

He massaged Judson’s shoulder lovingly. Quite suddenly it had come to him that the problem which had been weighing him down was no problem at all. He had been mistaken in supposing that two alternatives of action presented themselves. Now that the sudden spectacle of Judson had, so to speak, stressed the Coker motif in the rhythm of life, he saw clearly that there was only one course for him to pursue. At whatever cost to himself and his financial future he must keep faith with Alice. The fishing-trip was on, the spectacular entry into the pulp-and-paper business off.

“Hullo, Bill o’ man,” said Judson. “Just the fellow I want to see. As a matter of fact, I came out here specially to see you. Say, listen, Bill. Alice has been tipping me off about what’s happened at home. There’s no mistake about this fishing-trip, is there? Because if there is I’m in very Hollandaise. A week at the old lady’s would finish me.”

“That’s all right.” Bill patted his shoulder. “I promised Alice and that’s enough. The thing’s settled.” Bill hesitated blushfully for a moment. “Judson, old man,” he went on, his voice trembling, “I asked her to be my wife.”

“Breakfast every morning at seven-thirty, if you can believe it,” said Judson. “And working on the farm all day.”

“To be my wife,” repeated Bill in a slightly louder tone.

“And if there’s one thing that gives me the pip,” said Judson, “it’s messing about with a bunch of pigs and chickens.”

“I asked Alice to marry me.”

“And then family prayers, you know, and hymns and things. I couldn’t stand it, o’ man; simply couldn’t stand it.”

“She wouldn’t give me a definite answer.”

“Who wouldn’t?”

“Alice.”

“What about?”

Bill’s attitude of general benevolence towards the Coker family began to undergo a slight modification. Some of its members, he felt, could be a little trying at times.

“I asked your sister Alice to marry me,” he said coldly. “But she wouldn’t actually promise.”

“Well, that’s fine,” said Judson. “I mean, you can get out of it all right, what?”

Revolted as Bill was—and he gazed at his friend with a chilly loathing which might have wounded a more sensitive man—his determination was not weakened. Judson might have rather less soul than a particularly unspiritual wart-hog, but he still remained Alice’s brother.

“Wait here,” he said stiffly. “I must go and see my uncle.”

“Why?”

“To tell him about this fishing-trip.”

“Does he want to come, too?” asked Judson, perplexed.

“He wants me to go to work in his office at once. And I must tell him that it will have to be postponed.”

Mr. Paradene had left the study when Bill got there, but he found him in the library.

“I wanted to see you, William,” he said. “Sit down. I was just going to ring for Roberts to tell you to come here. I have a suggestion to make.”

“What I wanted to say——”

“Shut up!” said Mr. Paradene.

Bill subsided. His uncle scrutinised him closely. There was something appraising in his glance.

“I wonder if you have any sense at all,” he said.

“I——”

“Shut up!” said Mr. Paradene.

He sniffed menacingly. Bill began to wish that he had some better news for this fiery little man than the information that he proposed to abandon the idea of work and go fishing.

“You’ve always been bone-idle,” resumed Mr. Paradene, “like all the rest of the family. But there’s no knowing whether you might not show some action if you were put to it. How would you like me to continue your allowance for another three months or so?”

“Very much,” said Bill.

“Mind you, you’d have to do something to earn it.”

“Certainly,” agreed Bill. “After I come back from this fishing——”

“I can’t go myself,” said Mr. Paradene, meditatively, “and I ought to send someone. There’s something wrong somewhere.”

“You see——”

“Shut up! Don’t interrupt! This is the position. The returns of my London branch aren’t at all satisfactory. Haven’t been for a long time. Can’t make out why—my manager there struck me as a very shrewd fellow. Still, there’s no getting away from it, the profits have been falling off badly. I’m going to send you to London, William, to look into things.”

“London?” said Bill blankly.

“Exactly.”

“When do you want me to go?”

“At once.”

“But——”

“You’re wondering,” said Mr. Paradene, placing an erroneous construction on his nephew’s hesitation, “just exactly what I expect you to do when you get to London. Well, frankly, I don’t know myself, and I don’t quite know why I’m sending you. I suppose it’s just with the faint hope of discovering whether you have any intelligence at all. I certainly don’t expect you to solve a mystery which has been puzzling a man like Slingsby for two years.”

“Slingsby?”

“Wilfrid Slingsby, my London manager. Very capable man. I say I don’t expect you to go straight over there and put your finger on the solution of a problem that has baffled a man like Slingsby. All I feel is that, if you keep your eyes open and try to learn something about the business and take an interest in its management, you may happen by luck to blunder on some suggestion which, however foolish in itself, might possibly give Slingsby an idea which would put him on the right track.”

“I see,” said Bill. The estimate of his potentialities as factor in solving the firm’s little difficulties was not a flattering one, but he had to admit that it was probably more or less correct.

“It’ll be good training for you. You can go and see Slingsby and he can tell you something about the business. That will all help,” said Mr. Paradene with a chuckle, “when you come back here and start addressing envelopes.”

Bill hesitated.

“I’d like to go, Uncle Cooley.”

“There’s a boat on Saturday.”

“I wonder if I could have half an hour to think it over?”

“Think it over!” Mr. Paradene swelled ominously. “What do you mean, think it over? Do you understand that I am offering you——”

“Oh yes, I quite see that—it’s only—— Look here, let me just pop downstairs and speak to a fellow.”

“What are you talking about?” demanded Mr. Paradene warmly. “Why downstairs? What fellow? You’re gibbering!”

He would have spoken further, but Bill was already at the door. With a deprecating smile in his uncle’s direction, intended to convey the message that all would come right in the future, he edged out of the room.

“Judson,” he said, reaching the hall and looking about him.

He perceived that his friend was engaged at the telephone.

“Half a minute,” said Judson into the instrument. “Here’s Bill West. Just talking to Alice,” he explained over his shoulder. “Father’s come home and he says it’s all right about that trip.”

“Ask her to ask him if it will be as good if I take you over to London instead,” said Bill hurriedly. “My uncle wants me to go over there at once.”

“London?” Judson shook his head mournfully. “Not a chance! My dear old chap, you’re missing the whole point of this business. The idea is to dump me somewhere where I can’t——”

“Tell her to tell him,” urged Bill, feverishly, “that I will pledge my solemn word that you shan’t have a cent of money or a drop of drink from the time you start to the day you get back. Say you’ll be just as safe in London with me as——”

Judson did not permit him to finish the sentence.

“Genius!” murmured Judson, a smile of infinite joy irradiating his face. “Absolute genius! I should never have had the gall to think up anything like that.” His face clouded again. “I doubt if it’ll work, though. Father’s not a chump, you know. Still, I’ll try it.”

There was a telephonic interval, at the end of which Judson relaxed and reported progress.