Pearson’s Magazine (US), July 1906

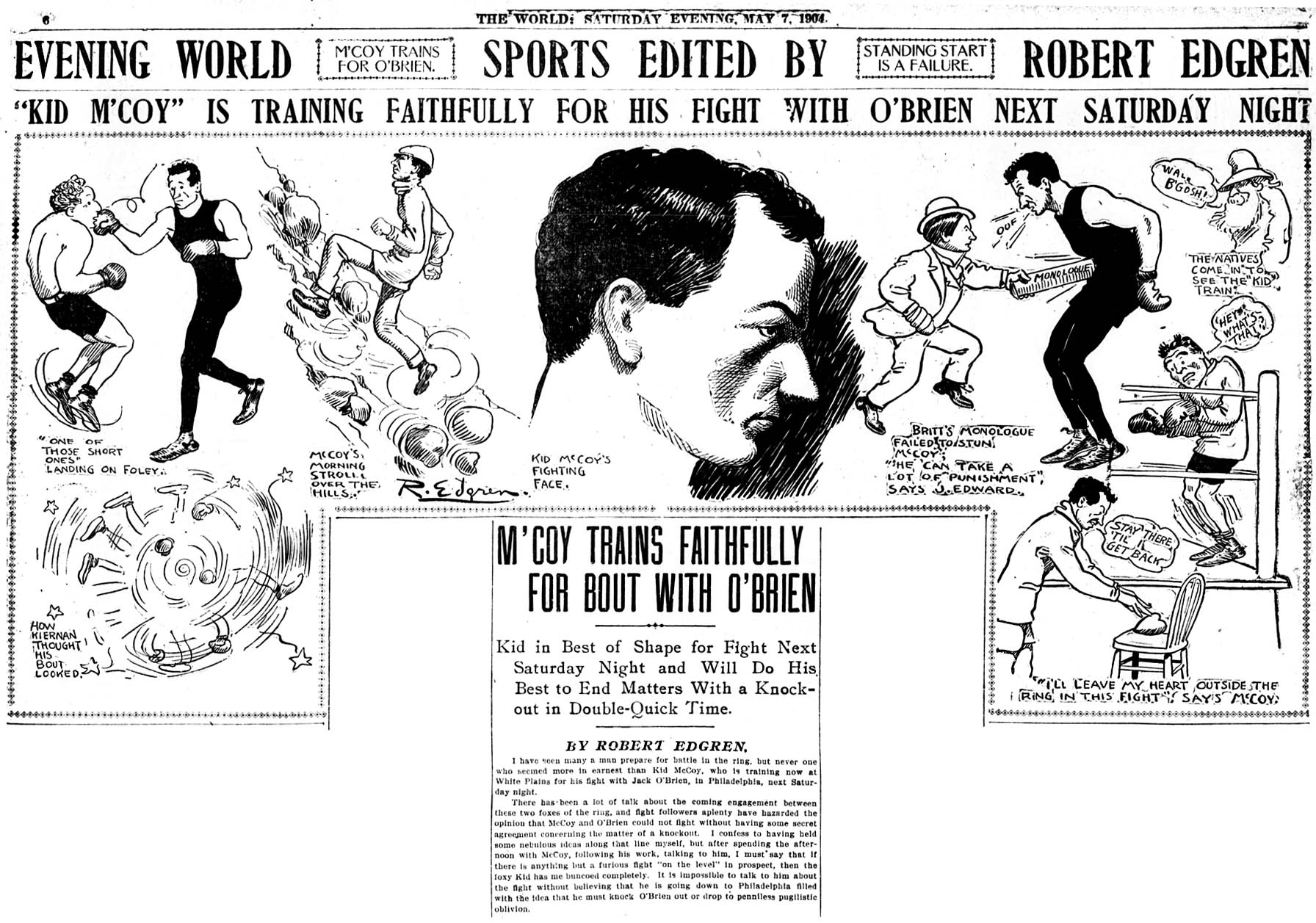

HE Kid sat

in the spring sunlight on the low veranda of the Wheatsheaf Hotel at Green

Plains, reading lazily through a copy of a New York evening paper, which had just

come in. The tenth page was half filled with sketches of a humorous nature. He

caught sight of his own name, and glanced at them; they were flattering in

motive, but candid in detail. They caricatured the Kid, but represented him in

the act of performing great feats. One of them pictured certain typical

inhabitants of Green Plains coming down from a mountain hut, leading cows and

pigs, which, according to the legend beneath, they purposed to wager on the Kid’s

success in his next fight. In another sketch, Peter Salt was represented flying

through the air on receiving one of the champion’s scientific drives.

HE Kid sat

in the spring sunlight on the low veranda of the Wheatsheaf Hotel at Green

Plains, reading lazily through a copy of a New York evening paper, which had just

come in. The tenth page was half filled with sketches of a humorous nature. He

caught sight of his own name, and glanced at them; they were flattering in

motive, but candid in detail. They caricatured the Kid, but represented him in

the act of performing great feats. One of them pictured certain typical

inhabitants of Green Plains coming down from a mountain hut, leading cows and

pigs, which, according to the legend beneath, they purposed to wager on the Kid’s

success in his next fight. In another sketch, Peter Salt was represented flying

through the air on receiving one of the champion’s scientific drives.

“Up at Green Plains,” said the paper, “there is a man who will own the whole town if he wins his next fight. His name is Kid Brady, and to the inhabitants of that noble joint there is not a bigger man in the world. He went up there the other day to train for his fight with Jimmy Garvis, which takes place at Philadelphia on the 14th; and now every man, woman, and child for miles around talks about him. Between whiles the Kid takes photographs with his nice new snap-shotter. As views of representatives of American beauty, his photographs of Mike Mulroon and Peter Salt have Burr Intosh beat to a standstill every time.”

In short, the Kid was on active service again, and glad to be there. His old opponent, Jimmy Garvis, had been very busy of late. He had fought two fights, and won both with ease; and the public began to talk about a return match with the Kid. The champion was delighted to meet them half way.

So Jimmy Garvis threw down his glove, and the Kid picked it up with alacrity. The two met in the most friendly fashion at dinner at a sporting restaurant, and signed the articles. A “play or pay” match, either party not putting in an appearance in the ring to forfeit his money, and the loser to get a proportion of the purse. Having settled these weighty matters, the pair shook hands, and parted, Jimmy Garvis to Atlantic City, the Kid to his favorite Green Plains.

He loved to train at Green Plains. The writer of the newspaper report had added picturesque touches here and there, but in the main his statements were correct. Green Plains was fond and proud of the Kid, and was backing his chances at Philadelphia with more than it could afford to lose with any comfort. Whenever the Kid walked abroad in the village, groups of gray-bearded, slouch-hatted farmers rallied around to inquire after his health. Later, they usually retired to drink it.

They were certainly justified in risking their belongings on the champion’s chances. The Kid had one very important advantage over a great many of his rivals. He did not drink. In or out of training, he touched no alcohol of any description. On one occasion a hearty person, who had come all the way from Denver to see him, burst into his saloon with a cheery “What’s yours, Mr. Brady?” The Kid had ordered a lithia water, and the man from Denver was nearly a fortnight getting over the shock of it. Jimmy Garvis, on the other hand, was in the habit of running loose when not in training. Fur coats and cigars a foot long were Jimmy’s simple pleasures, together with divers “small bottles.” The consequence was that he needed stricter handling than the Kid when a fight was in preparation. The Kid’s training was merely a development of his everyday life.

Mike Mulroon was charmed with his man’s progress. As he explained volubly to Peter Salt every evening when the Kid had gone to bed, the boy trained himself. He never showed signs of even wanting to do the things which he ought not to do. He abandoned smoking without a murmur. He took Peter Salt’s hardest blows with unruffled cheerfulness. He never lost his appetite. Twelve miles go-as-you-please along the country roads never wearied him. His conversation, though there was not much of it—he was never garrulous when training had once begun seriously—was bright. He never lay awake at nights. And now, two days before the battle, he was down to the prescribed weight, and as full of life as a kitten. What was not steel was india-rubber.

“Kid,” said Mike Mulroon, as he rubbed him down after his brine bath, “yer a fool. An archangel couldn’t have trained better. Faith, afther ye’ve put Jimmy to sleep, ye’ll have to give an exhibition spar, or the people will be afther complainin’ that they have not had the worth of their money. It won’t go into a second round.”

And even Peter Salt had been moved from his wonted silence, and had congratulated the Kid in measured speech.

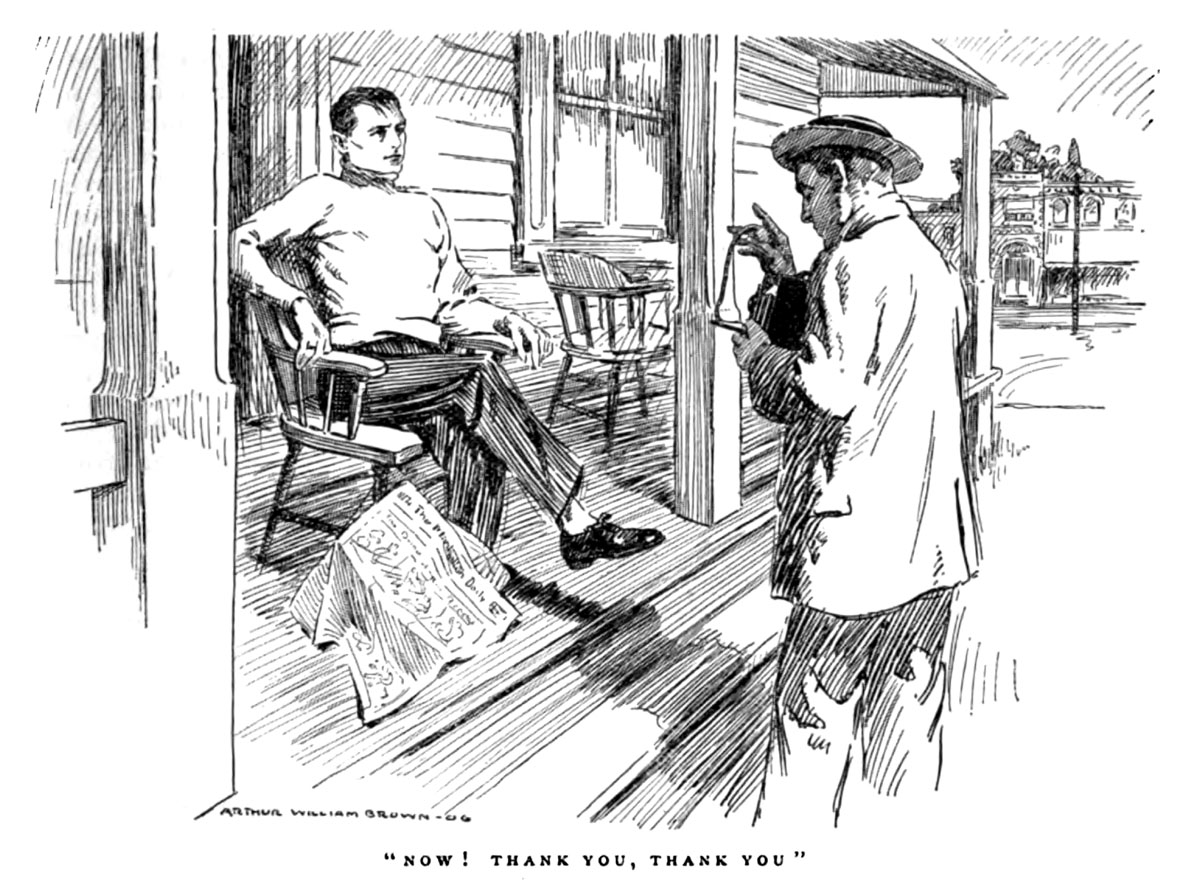

The Kid dropped the paper beside his chair, and looked around about him. The grass-grown square was empty. The veranda was empty. A sudden desire came over him to talk to some one. Mike and Peter had gone for a stroll through the town. There was nobody near. But as he looked down the road, he was aware of a man walking in the direction of the hotel. His eyes lit up as he perceived that the man carried a camera. The Kid had only recently been bitten by the craze for taking photographs, and he was at the stage where the victim’s chief pleasure is to foregather with another victim, and talk camera to him.

The man paused opposite the veranda, and fanned himself with his handkerchief. When he removed his hat, the Kid saw that he had gray hair.

“Good afternoon,” said the man.

“Afternoon,” said the Kid.

“Can you tell me where I can find Mr. Brady?”

“My name.”

“Then may I ask you,” said the man with a friendly smile, “if you would mind sitting there while I take a photograph of you?”

“Sure,” replied the Kid. “I take photographs.”

“So I saw in the papers. I must show you my camera when I have taken you. It’s a new make. Now! Thank you, thank you. Poof! This is warm weather, sir, for the time of year.” The Kid agreed. The man entered the veranda and drew a chair up beside the champion’s. The next moment their heads were close together, inspecting the camera, which was of a new make.

The Kid noticed that his friend kept shooting sharp glances at him from time to time, as he explained the mechanism of his camera. Frequently he would catch his eye, and on such occasions he always detected something searching in his gaze, as though he were trying to read some secret there. It might have been a mere mannerism, but it embarrassed the Kid. The man with the camera quickly showed that there was method in what he did. He turned to the Kid with some abruptness.

“You will excuse me, sir,” he said, “but are you aware that there is something decidedly wrong with your eyes?”

The Kid stared.

“My eyes?” he repeated. “What’s the matter with them?”

“If you want the technical term,” said the man, “it’s amblyopia.”

“What’s that?” said the Kid.

“It is an affection of the eyes. In your case very pronounced. I wonder you have not noticed it yourself.”

“My eyes are the best ever. I can see anything.”

“That, I fear, signifies nothing. There is such a thing as seeing too well. Do your eyes get tired easily?”

“Never.”

“Headaches ever?”

“Not one. Not when I’m in training,” he added.

The man caught him up at once.

“Ah, then you do have them when you’re out of training? How often?”

“Twice a year,” hazarded the Kid.

The man shook his head.

“Bad,” he muttered, “bad. I think I see now. You smoke when not in training?”

“Sure.”

“But knock it off when you have a fight on hand?”

“Sure.”

“Now I understand. You have tobacco amblyopia.

“I don’t know how much you smoke; but a man with your eyes ought never to have smoked at all. I am surprised that you have had no trouble with them before this. I attribute it to the fact that you are continually leaving off smoking for long periods at a time. That has acted as a check on the disease.”

“But what is it? Can’t it be cured?”

“That I cannot tell you from a cursory examination. I should say with care, yes. But I cannot say for certain unless I test your eyes carefully. Have you ever been to an oculist?”

“Never.”

“You should have gone. Well, fortunately, I am an oculist by profession myself. You may have heard my name? Theodore Shaw, of Boston. No?

“Well, well, it shows one how purely local a reputation of my kind is. If you wish it, I will examine your eyes, Mr. Brady. I cannot do it very thoroughly, of course; but it may enable me to give you some advice which will be valuable to you. Shall we go into the hotel?”

What followed was Greek to the Kid. In a little room at the back of the hotel Mr. Shaw put him through a series of what seemed to him meaningless maneuvers, asked him a good many apparently irrelevant questions, held a candle before his eyes, shook his head a great many times, and finally led him out into the sunlight once more.

“Well?” queried the Kid anxiously.

“The disease,” said the man slowly, as one who weighs his words, “has not gone too far. It can be cured. But you must be careful. Very careful. No more smoking, I need hardly say.”

“Not another cigar,” said the Kid fervently, “if Teddy Roosevelt offered it me himself.”

“You must take great care not to strain the eyes.”

“You bet I will.”

“And there is another thing. And I am afraid,” added the man, “that this puts you in a very difficult position.”

“Yes,” said the Kid.

“It is this. In their present condition any blow, even the slightest, would have a very injurious effect on your eyes.”

The Kid’s jaw fell. He looked blankly at the speaker.

“Yes,” he went on, “a tap would injure them. A really severe blow would almost certainly destroy your eyesight altogether. I understand that in a few days you are to fight the ex-champion at Philadelphia. Well, I can only say that it will be suicidal for you to attempt any such thing. I am sincerely sorry for you; but it is necessary that you should know the truth before it is too late. It was providential that I happened to come here this afternoon.”

The Kid sat staring across the square with unseeing eyes. He hardly heard what was being said to him. A drummer drove past in his cart, and shouted a cheerful greeting to him. He returned it mechanically. There seemed to be a weight on his brain which deprived him of the power of thinking.

He became aware that his companion was bidding him good-by. He caught some remark about a train. He stood up, and shook hands, scarcely knowing what he did.

“And if you will take my advice,” the stranger concluded, “you will make arrangements at once for withdrawing from this fight. It is a large sum to forfeit; but what is it in comparison with sight?”

“But if I don’t fight . . . the bets! They’re bettin’ on me everywhere. If I quit, every one who has bet on me will lose their money.”

“That is true. But even that is surely not worth considering. Think of it. Think what blindness means! At your age! Well, I must go. Good-by again. I shall leave you to think it over.”

And the last the Kid saw of the man from Boston was the tail of his coat disappearing rapidly around the comer of the square, as he hurried off to the station.

The Kid sat on, thinking. His brain was clearer now, and he could weigh matters better. On the one hand, there was blindness. He shut his eyes, and tried to realize what this meant. Everlasting darkness. And all because he had done what every other man he had ever met had done. It was hard. Mike would be back soon. He would tell him everything, and the fight would be canceled. But the thought of Mike brought back to him the reverse side of the picture. Play or pay. Fight or forfeit. Mike, he knew, had betted heavily on him, as he always did. He could not sell him. And the thousands who had done the same. He could not sell them. There were farmers at Green Plains who had wagered their savings on him. It was his duty to go through with his contract. He could not draw back now. And yet——

Fumbling in his pocket, his fingers came in contact with a coin. An idea struck him, and he drew it out. Play or pay? Sudden death——

The coin spun up in the eye of the sun, and rolled across the white, dusty road. It was a nickel. If it fell with the V uppermost—no, with the head—no, the V—He wavered, undecided. Then he pulled himself together. The V it should be. If the head was underneath, he would fight.

His heart was beating fast, as he stepped into the road.

Half way across he came upon it, almost buried in the dust.

It was the V.

“Mike,” said the Kid next day, “I think I won’t put the gloves on with Peter. I’ve had enough sparring. I’ll take it out with the bag.”

“Very well, Kid,” said Mulroon. “Ye’re a quare boy with yer fancies. But yer down to the weight, so it don’t matter.”

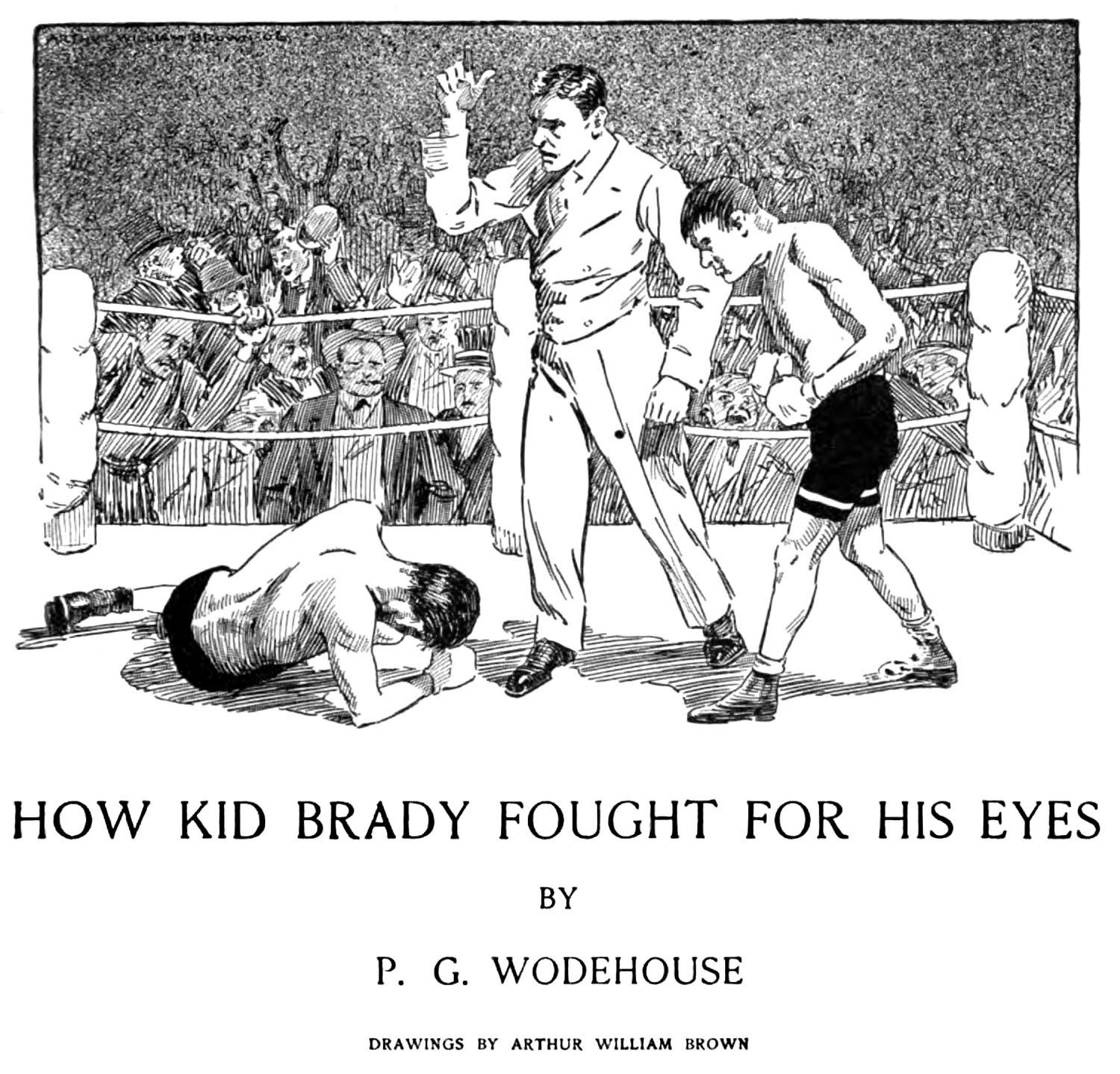

A volley of shouts came from all corners of the hall as the ex-champion’s right glove neatly passed the Kid’s guard, and left an angry red mark on his side. There was a brief rally, and the fighters clinched.

“Get a move on, Jimmy,” cried a voice from near the door, “it’s all your own.”

“Clever, Kid; box clever!” This in the accent of New York.

“Silence there during the rounds.”

“Break away,” said the referee curtly, walking between the two men. Their arms relaxed their hold, and they stepped back a pace. The Kid had a swift sight of his antagonist’s flushed face as he dashed in in his hurricane style. His left flashed out, and met empty air; he was conscious of a great, but curiously vague, shock. Something seemed to snap at the back of his head.

A face appeared beside him, working violently. He recognized it as Mike Mulroon’s. He wondered idly why there should be no more of Mike but a head and shoulders. Then it struck him that he was lying on the stage. His eye was caught by a movement in the air above him. A man in evening dress was standing by his side, sawing rhythmically with his right arm. There was a great deal of noise. He heard his own name shouted. Some one was telling him to get up. Mike again. Why did Mike want him to get up? He felt very comfortable where he was; though something made it difficult for him to think coherently. Somebody was counting. He could just hear him through the din—“Seven . . . Eight.” Then he realized.

The next moment the roar of the audience changed to a crescendo. The Kid was up again. Staggering, but on his feet. Hope still remained.

Jimmy Garvis, waiting with every muscle tense on the other side of the ring, sprang forward like a tiger to complete the work his cross-counter had begun. Instinct told the Kid to slip, and he was in the middle of the ring, with his opponent turning back to press him again. Another slip. This time he was by the ropes.

As his opponent rushed, there came from behind him the penetrating sound of a gong, and the applause broke out again. The third round was over.

“Where’s your three to two now?” said the Californian by the door triumphantly to his neighbor. The other, whose home was New York, did not reply. He was beginning to wish, like many others present that night, that he had kept his dollars safely in his pocket instead of wagering them on the champion. The Kid was filling his supporters with consternation. From the first round he had fought like a novice. All the dash and fire which had won him the championship were missing. His attitude was strained and awkward. His leads were hesitating, ineffective. If he had not been Kid Brady, whose gameness it was absurd to question, one would have said that he was afraid. And so he was. For the first time in his life, the Kid knew what fear meant. He was sick with the terror of receiving his opponent’s hurricane swings in his eyes. All his thoughts were concentrated on saving them. And so far he had been successful. But like a cold hand on his heart the thought haunted him that it could not last. Sooner or later the fatal blow must get through.

It happened before the fourth round had been in progress for thirty seconds. Jimmy Garvis feinted, drew the Kid’s counter, and got home heavily. The Kid staggered back on the ropes, with lights dancing before his eyes. Another second, and they had cleared. But the mischief was done.

And now there came over him a complete revulsion of feeling. The worst had happened. The suspense was over. He was conscious of no sensation other than of icy rage. He forgot that he was boxing for a prize. His opponent seemed to him inhuman, some relentless devil maliciously intent on destroying him. There was a moment’s pause, while the two sparred for an opening; and then the Kid went in with a vicious fury which made this fight a topic of conversation for years afterward in the smoking-rooms of Philadelphia and New York. There was no staying such an onslaught. Twice the ex-champion fell, to rise gallant, but weak, to renew the contest. He reeled across the ring like a rudderless derelict. Every one was standing up now. It was plain that the end must come soon.

For the third time the Californian went to the floor. The Kid, standing over him, was forced back to the farther side of the ring. The referee’s hand rose and fell. A dead silence had gripped the spectators, and the referee’s voice sounded thin and clear as he counted out the ten seconds of grace.

“Six . . . Seven.”

Jimmy Garvis struggled to his knees. His gloved hand wandered out and clutched the ropes.

“Eight . . . Nine.”

The hand relaxed, and he sank to the boards again.

“Ten,” said the referee, and waved his arm toward the Kid.

“Take me away, Mike,” said the Kid. “I must see an oculist.”

“Brady,” said the oculist. “Not Kid Brady, the champion?”

“I’m Kid Brady. Look at my eyes. Is there any hope?”

“While there is beefsteak,” said the oculist solemnly, “there is always hope. But it is certainly a very fine black eye. You’ve come to the wrong man, my boy. You should have gone to a butcher.”

“Will I go blind?”

The oculist looked at him curiously, and patted him on the shoulder.

“You’re unstrung, my boy. I don’t wonder, if you’ve come straight from a championship fight. Sit down and rest a while. It will soon pass off.”

“I’ve got tobacco am—amblyopia,” said the Kid, “and I’m going blind. He said a hard blow would do it.”

“He. Who is he? And what do you know of amblyopia? But I’ll look at your eyes, if that will set your mind at rest. Now.” He rose, and turned on an electric light. “Sit down. Now look straight here where I am pointing. That’s right. Don’t move.”

A light flashed into the Kid’s eyes. The oculist was examining them through a small glass. Twice the light flashed, and then the oculist laid down the glass.

“Amblyopia!” he said. “You’ve no more got amblyopia”—he looked around him for a suitable simile—“than the table,” he added.

“How on earth do you get these ideas into your head? My dear boy, don’t do that! Bear up.”

For under the strain of the fight and the fright and the relief of it all the Kid’s nerves had given away suddenly and completely, and he was sobbing like a child.

“Drink this,” said the oculist briefly. The Kid broke through his principles, and felt the better for it.

“Now, let me hear all about this. Who has been telling you that your eyes were wrong?”

“Dr. Shaw.”

“And who in the name of all the saints you have never heard of is Dr. Shaw?”

“Dr. Theodore Shaw, of Boston. A famous oculist.”

“Famous, is he?” said the other drily. He fumbled among the books on the table, and produced a red-backed volume. “Just glance through the S’s in this book, and if you find your friend Shaw there I’ll give you as many dollars as you won to-night.”

“It’s not there,” said the Kid, having searched.

“So I imagined. That book contains the names of all the oculists, known and unknown, in the country. You would think a famous man like Dr. Theodore Shaw, of Boston, would be there, wouldn’t you?”

The Kid looked dazed.

“But——?” he began.

“My dear boy,” said the oculist, “I don’t know very much about the modern ring, but I do know that people bet on fights. And when people bet, there are apt to be shady tricks. If you cannot see now that this was a low dodge to induce you to give up the fight, you are blinder even than Dr. Theodore Shaw prophesied that you would be.”

Then the Kid saw.

His voice trembled when next he spoke.

“If I could find him——” he said, clenching his fists and breathing heavily.

“There was once,” said the oculist sententiously, “an optimistic gentleman who tried to find a needle in a haystack. He did not succeed.”

Notes:

Wheatsheaf Hotel: Here Wodehouse’s brief acquaintance with America (five weeks in 1904) fails him; though Wheatsheaf is a common name for English inns and pubs, it does not seem to be used thus in the USA. Dorothy L. Sayers would later use Wheatsheaf as the name of an inn in Fenchurch St. Paul in the English fen country in her 1934 novel The Nine Tailors. [NM]

Green Plains: as in the earlier instance of Garvin and Garvis, Wodehouse here misremembers a feature of his original serial, now running for nearly a year. The second installment of the serial identifies White Plains as the Kid’s training grounds. See “How Kid Brady Broke Training” and the White Plains, NY endnote to that story.

New York evening paper … tenth page: No proof can be established at this remove of time, but given the “tenth page” detail, it is reasonable to speculate that the paper was the Evening World. We know (see endnote at this link) he read that paper on his 1909 visit to New York, and the Library of Congress Chronicling America website has a scan of the Sporting Edition of the paper of May 10, 1904, while Wodehouse was in New York on his first visit to America, during which he met Kid McCoy at his White Plains training camp. The tenth page contains humorous sketches of boxer Robert Fitzsimmons. But even more compelling is the page whose sketches and lead article feature the training of Kid McCoy in the May 7, 1904 issue. The scan here is from page 6 of the Final Results Edition, often containing fewer pages than the Sporting Edition. Right-click on the image below for a magnified view of the sketches; click on the previous link for the full page, including the continuation of the article. Note that the upcoming fight with Jack O’Brien is to be in Philadelphia, the same location as Kid Brady’s fight in the story; note also the “gray-bearded, slouch-hatted farmer” in the upper right corner. Also, when the rough outline of the Kid Brady saga was later incorporated into Psmith, Journalist, we are told that “Edgren, in the Evening World, had a paragraph about his chances for the light-weight title.”[NM]

sketches of a humorous nature: clearly a subsidiary interest on Wodehouse’s mind here is the move toward photojournalism and away from sketches to illustrate story, a concern readers caught in the November 1905 installment previously. See “How Kid Brady Broke Training” where a “misty photograph” of the Kid on the sporting page is mentioned.

sketches of a humorous nature: clearly a subsidiary interest on Wodehouse’s mind here is the move toward photojournalism and away from sketches to illustrate story, a concern readers caught in the November 1905 installment previously. See “How Kid Brady Broke Training” where a “misty photograph” of the Kid on the sporting page is mentioned.

They caricatured the Kid: caricature was a favored mode of illustration since it both disguised breaches of realism and enabled works to get to press faster and therefore to make deadline; caricatures were well-established features of the popular press and extended back to the early 1820s and the weekly publications of Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle.

one of the champion’s scientific drives: one of Brady’s calculated offensive attacks or volleys; the illustration will prove both ironic and prophetic given that Brady will fight an almost exclusively defensive campaign against Garvis—save only the decisive offensive that ends the fight. [For more on “science” in boxing, see the endnotes to the third story in this series. —NM]

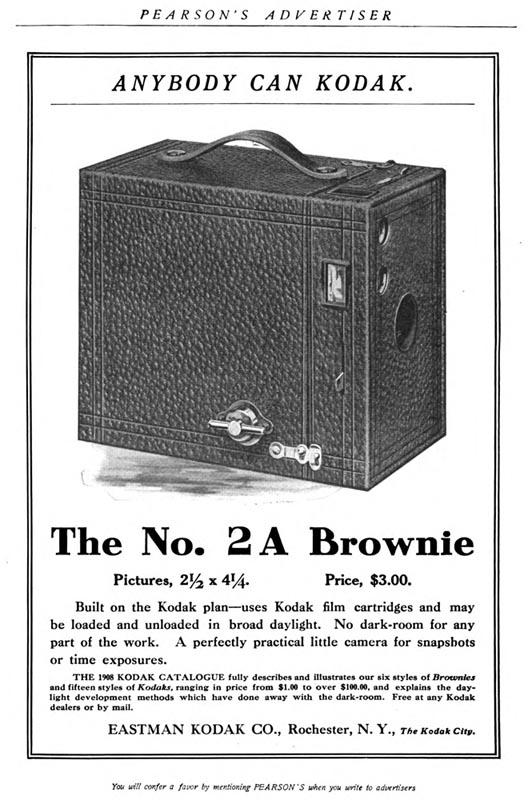

photographs with his nice new snap-shotter: likely the Kodak Brownie, “the little camera that does big things,” introduced in February 1900. Given that Kodaks were advertised in Pearson’s Magazine, this and subsequent allusions amounts to early product placement. The advertisement at right, for instance, appeared in the July 1908 issue.

photographs with his nice new snap-shotter: likely the Kodak Brownie, “the little camera that does big things,” introduced in February 1900. Given that Kodaks were advertised in Pearson’s Magazine, this and subsequent allusions amounts to early product placement. The advertisement at right, for instance, appeared in the July 1908 issue.

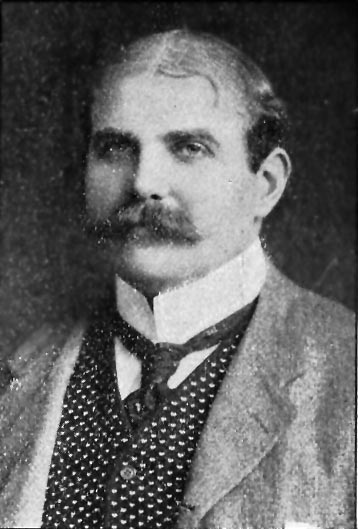

Burr Intosh: Burr William McIntosh, b. 21 August 1862 (Wellsville, Ohio), d. 28 April 1942 (Hollywood, California). McIntosh was a noted figure in publishing and photography and later in silent film. His sister Nancy was an operatic soprano and the adopted daughter and heiress of W. S. Gilbert of Gilbert and Sullivan. He distinguished himself in collegiate and amateur athletics in sprinting and hurdles, and acted on American and British stages beginning in 1885, also turning to newspaper work, including serving as a war correspondent and photographer in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Before he started his career in silent film in 1914, eventually appearing in 53 silent films throughout his career, he published the Burr McIntosh Monthly, a society-and-art rag from 1903 to 1910 featuring his glamorous photographs of famous people. [The photo at left is from a 1903 guide to his hometown and its leading celebrities, the closest portrait in time to the period of the magazine that could be found. Wodehouse’s story “Misunderstood” would appear in the May 1910 issue. —NM] He also owned a film studio and was active in early radio.

Burr Intosh: Burr William McIntosh, b. 21 August 1862 (Wellsville, Ohio), d. 28 April 1942 (Hollywood, California). McIntosh was a noted figure in publishing and photography and later in silent film. His sister Nancy was an operatic soprano and the adopted daughter and heiress of W. S. Gilbert of Gilbert and Sullivan. He distinguished himself in collegiate and amateur athletics in sprinting and hurdles, and acted on American and British stages beginning in 1885, also turning to newspaper work, including serving as a war correspondent and photographer in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Before he started his career in silent film in 1914, eventually appearing in 53 silent films throughout his career, he published the Burr McIntosh Monthly, a society-and-art rag from 1903 to 1910 featuring his glamorous photographs of famous people. [The photo at left is from a 1903 guide to his hometown and its leading celebrities, the closest portrait in time to the period of the magazine that could be found. Wodehouse’s story “Misunderstood” would appear in the May 1910 issue. —NM] He also owned a film studio and was active in early radio.

That Wodehouse references McIntosh as a figure of note in 1906 suggests that Wodehouse himself was in the know about American popular culture and the interests that came together in its composition, perhaps even that his success as a writer and subsequent contributor to that culture was not accidental or unsought after, as he evasively reports, for instance, in his 1969 Preface to the reissued Something Fresh, but was part of a carefully orchestrated plan to join the popular elites of the twentieth century.

A “play or pay” match: both suggesting the darker side of the fight game. A play match typically didn’t generate enough money-interest to decide the match in either fighter’s favor, so that fighters typically fought tentatively, without instruction and without knowing when to take the fall. A pay match was geared towards big money and could be orchestrated with the aim of further influencing the betting purse or, with large sums already decided, with sensationalism and the outcome in full view.

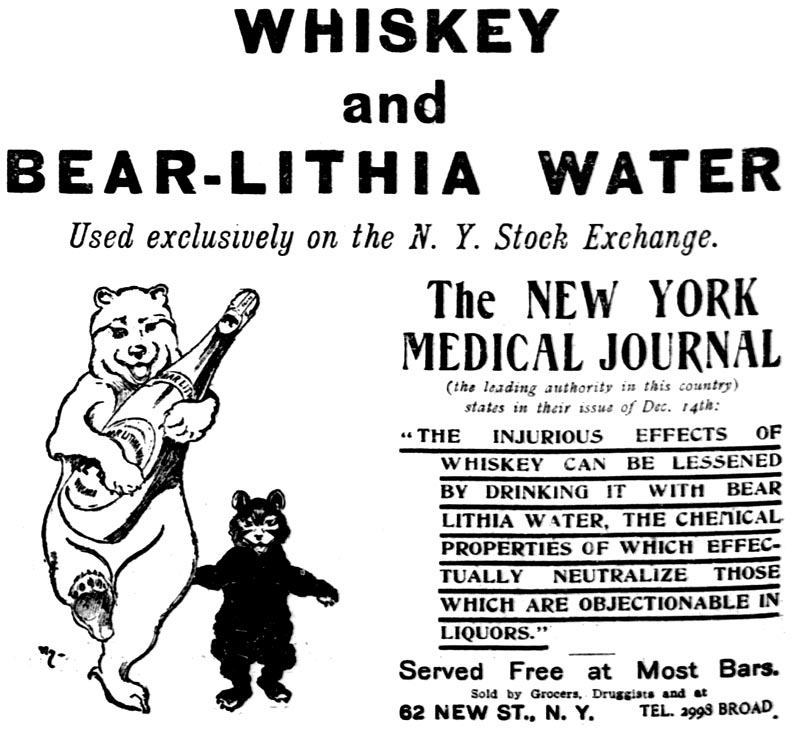

lithia water: a mineral water containing lithium salts advertised to neutralize ill effects in alcohol; see this New York Daily Tribune advertisement, 13 December 1901:

lithia water: a mineral water containing lithium salts advertised to neutralize ill effects in alcohol; see this New York Daily Tribune advertisement, 13 December 1901:

a fortnight: i.e., two weeks; a clipped form of “fourteen nights”

“small bottles”: euphemism for drugstore bottles, therefore denoting a drug dependency, either prescription or not. Also possibly a euphemism for hard liquor, as in the flasks that enable easy transport.

the things which he ought not to do: smoking, drinking, bad diet, socializing, enjoying the company of women

with unruffled cheerfulness: denoting the Kid’s good humor but more importantly his tendency not to get flustered, not to lose his head in a fight, even a sparring match. Typically, such concepts have to be taught or reinforced during training.

What was not steel was india-rubber: muscle and sinews or joints, a finely turned-out athlete

after his brine bath: to toughen the skin and help prevent skin-tears during fights; boxing lore is filled with such remedies, from chewing frozen steak to toughen the jaw to washing the face in pickle juice or brine to toughen the skin.

The Kid had only recently been bitten by the craze for taking photographs: hobby photography dates from precisely this era, with the advent of the Eastman Kodak Company’s “Brownie” model camera, a do-it-yourself, user friendly model that allowed film to be loaded directly into an exposure chamber that could afterward be removed for processing. Wodehouse again is clearly up to date on the technological innovations of his time.

It’s a new make: likely a Kodak “Brownie”; the Kid’s interest in photography would clearly have been published in the press, perhaps as part of the picturesque touches noted above, so that this episode should strike readers as opportune and hardily a chance meeting; indeed, the entire episode here does not merely revisit the superstitious nature of Brady’s character, as in the fruitarianism of the November 1905 installment (“How Kid Brady Broke Training”), but seems uncharacteristically forced and plodding, suggestive almost of a lack of interest in the material, a supposition supported by the growing irregularity of the installments. [Shaw’s camera in the illustration by Arthur William Brown, however, is not a box Brownie but seems to be a folding roll-film camera with a lens bellows and bulb-operated shutter, perhaps similar to the Folding Kodak 4A, new in 1906. —NM]

Frequently he would catch his eye . . . to read some secret there: obviously a carefully planned stratagem, depending on the close proximity of faces enabled by the camera’s inspection. Readers should see the textual irony here; readers should get more than Brady gets. This is a ruse, a shuck and jive.

amblyopia: better known as “lazy eye,” typically an eye disorder from birth where one eye functions out of sequence with the other and where the brain might opt to shut down vision from the offending eye to prevent double vision or blurred vision. Sufferers of amblyopia are unable to focus with both eyes on a single point.

Over time, loss of visual acuity is a noted feature of the fight game, particularly for career fighters who suffer repeated abuse over many fights. Ocular injuries were practically a by-product of the fight game, though more typical of the career fighter. The Kid’s age here and the time he spent in the ring would make such an ocular injury highly unlikely.

tobacco amblyopia: a form of toxic amblyopia, again showing the Kid’s ignorance. The amount of tobacco usage that would cause such a disorder would involve a lifetime of abuse. Also, the odds of suffering a double-whammy punch-induced misalignment of sight and a chemical form of the disorder would be exceptionally improbable. Readers again are given to understand far more than Kid Brady. Wodehouse is indeed treating the character with very mild derision, a feature we do not typically acknowledge in his handling of protagonists.

In their present condition . . . a very injurious effect on your eyes: a bit heavy-handed in its irony

It was providential that I happened to come here this afternoon: again, a bit heavy-handed in its plotting of irony, suggestive perhaps of a general lack of interest or a waning interest in the Kid Brady material

It was a nickel: The Liberty Head or V nickel was produced from 1883 to 1913; the design by Mint Engraver Charles Barber had the head of Liberty on the obverse and a wreathed V (Roman numeral for five) on the reverse. (Photo courtesy National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History.) [NM]

It was a nickel: The Liberty Head or V nickel was produced from 1883 to 1913; the design by Mint Engraver Charles Barber had the head of Liberty on the obverse and a wreathed V (Roman numeral for five) on the reverse. (Photo courtesy National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History.) [NM]

It was the V: this entire episode involving the coin toss would have most certainly reminded contemporary readers of Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem “If,” particularly the poem’s third stanza, involving chance and the game of pitch and toss:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

The poem, a favorite of Wodehouse’s, concludes a number of subjunctive If you can do this challenges with the supposition “You’ll be a Man, my son!” The idea here recalled is one of a testing grounds. The Kid’s character is being tested, and again he will emerge as one with the right stuff.

quare: Irish-American dialectical pronunciation for “queer,” as in “peculiar” or “odd”; Mulroon’s assessment should most certainly remind readers of the fruitarianism episode from the earlier installment.

This in the accent of New York: readers might best imagine such an accent as a heavily spondaic line, where every syllable is stressed or accented, viz., Clév ér, Kíd; bóx clév ér!

“Silence there during the rounds”: the referee’s admonition against over-coaching while the rounds are in progress; indicative of the frustration that Mulroon and Salt, otherwise quiet men who let the Kid go about his business, feel as they watch the Kid refuse to mount an offensive

sawing rhythmically with his right arm: to count off the seconds from one to ten for the benefit of the crowd; also to establish a fair count that could not be contested afterward. Though a necessary adjunct to fair play, the arm count also has great staged or dramatic effect, as Wodehouse demonstrates here in his verbal cinematography.

a crescendo: musical metaphor denoting awareness of a gradual increase in volume and intensity of sound, typically conveying a new emotion that the listener is being cued to experience; Wodehouse’s verbal cinematography here is undeniable and the precursor of a staple in sports film today.

his cross-counter: a counter-offensive punch thrown when an opponent has advanced a jab, aimed at the opening the jab has exposed. This denotes a few things in fight parlance: going for the early knockout punch rather than fighting strategically, often indicative of fear and read as such by others in the fight game of the past. Counter-offensives also tend to respond to the opposition rather than aggressively dictate the tenor of a fight. Though cross-counters are perfectly normal, an overreliance on them could denote a tentativeness on a fighter’s behalf. Garvis evidently respects the Kid, a fact more than significant given Brady’s heavily defensive style in the match. From the perspective of the Kid’s corner, this would be excruciating, even infuriating to watch. No wonder Mulroon and Salt are vocal, earlier.

to slip: technically, to move slightly out of the path of a punch by bobbing the head and moving the body unpredictably, either from side to side or up and down; also a defensive feign or forward move toward the leading hand at the start of a punch and then a quick break away to the opposite side, often, as in both cases here, moving past the fighter.

Where’s your three to two now?: alluding to betting odds

His leads were hesitating, ineffective: Brady here refuses to mount an offensive charge for fear of opening his guard and letting in a blow that will hurt his vision. He’s defending rather than fighting.

feinted: feigned, to simulate or pretend

drew the Kid’s counter: a strategic drawing of the offense from an opponent, where a fighter appears to have left an opening but awaits the counter with a counter of his own. Such ploys often lead to a temporary abandonment of defense, as both fighters, as Wodehouse will point out shortly, spar for an opening. Again, Wodehouse’s detailed and seemingly effortless account of such moments speak to a deep understanding of the mysteries or guild secrets of the fight game. Wodehouse was no mere dilettante but a man deeply schooled in the language and culture of pugilism.

got home heavily: hit the target with force. The blow that gets home heavily has not been deflected by a block or otherwise neutralized by a protected or receding target. Such a blow typically immobilizes a fighter, opens a window for further offence, and, unless halted by the bell and the end of a round, often leads to knockdown.

sparred for an opening: occurs when both fighters simultaneously adopt an offensive position and must await the other to make a mistake that might be capitalized upon

For the third time the Californian went to the floor: the three knockdown rule was obviously not in effect at this time.

While there is beefsteak . . . there is always hope: cold raw beefsteak was placed on areas of heavy bruising to reduce swelling and draw blood. The remedy would remain a staple throughout Wodehouse’s career, as, roughly, would the phraseology. For instance, in Spring Fever (1948), Augustus Robb assesses the impressive shiner he has inadvertently given Mycroft “Mike” Cardinal, the result of too much drink and a tool bag swung at full force, intended to be hurled out of doors, “ ‘It wants ’avin’ a bit of steak put on it,’ said Augustus Robb with decision. His had been a life into which at one time injured eyes had entered rather largely. ‘You trot along to the larder, ducky, and get a nice piece of raw steak. Have him fixed up in no time. . . . You can’t beat steak” (Chapter 17).

And what do you know of amblyopia: here the ruse is up and the conflict resolved. The oculist’s sarcasm confirms the earlier irony and underscores Brady’s tendency to accept what he is told without critical reserve. Wodehouse here, though not in a heavy-handed manner, likely builds on the stereotype of the superstitious and intellectually challenged prize fighter.

The Kid broke through his principles: an indirect way of saying that Brady drank an alcoholic beverage that his previous training had forbidden.

If you cannot see now: another veiled dig at Brady’s lack of intelligence

If I could find him—: again, denoting intelligence level, rendering ironic the earlier “Then the Kid saw.”

—Notes by Troy Gregory, with additions by Neil Midkiff

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums

Madame Eulalie’s Rare Plums